Abstract

We describe a two-hybrid strategy for detection of interactions with transactivator proteins. This repressed transactivator (RTA) system employs the N-terminal repression domain of the yeast general repressor TUP1. TUP1-GAL80 fusion proteins, when coexpressed with GAL4, are shown to inhibit transcription of GAL4-dependent reporter genes. This effect requires the C-terminal 30 residues of GAL4, which are required for interaction with GAL80 in vitro. Furthermore, repression of GAL transcription by TUP1-GAL80 requires SRB10, demonstrating that the TUP1 repression domain, in the context of a two-hybrid interaction, functions by the same mechanism as endogenous TUP1. Using this strategy, we demonstrate interactions between the mammalian basic helix–loop–helix proteins MyoD and E12, and between c-Myc and Bin-1. We have also identified interacting clones from a TUP1-cDNA fusion expression library by using GAL4-VP16 as a bait fusion. These results demonstrate that RTA is generally applicable for identifying and characterizing interactions with transactivator proteins in vivo.

The yeast two-hybrid (1) and interaction-trap (2) systems are simple genetic strategies for detecting interactions between proteins in vivo. These techniques were developed consequent to the understanding that eukaryotic transcriptional activators have separable DNA-binding (DBD) and activation domains (AD) that function when fused to heterologous proteins (3). Interaction of an AD “prey” fusion with a DBD “bait” fusion protein produces a functional transactivator complex that activates reporter genes bearing upstream cis-elements for the DBD. One limitation of these strategies is that transcriptional activators cannot be used as baits. In this report we describe a modified strategy that addresses this problem.

The yeast general repressor protein TUP1 is recruited to specific promoters in a complex with the corepressor SSN6 by gene-specific DNA-binding proteins. TUP1/SSN6 complexes are recruited to glucose-repressed genes by MIG1, which binds the upstream repression sequence for glucose (URSG) (4) (see Fig. 1A). Repression by SSN6/TUP1 is associated with chromatin reorganization of a number of genes including the GAL4, GAL1, GAL10, SUC2, and MATa specific genes (5–8). This observation, coupled with the finding that the N terminus of TUP1 interacts directly with histone H3 and H4 tails (9), suggests that SSN6/TUP1 may repress transcription by organizing nucleosomes (10). Repression by SSN6/TUP1 is also affected by mutations to several RNA polymerase II holoenzyme-associated proteins, including the cyclin-dependent kinase/cyclin pair SRB10/SRB11 (11). This genetic relationship suggests that TUP1-mediated repression also involves modulation of RNA polymerase II holoenzyme function.

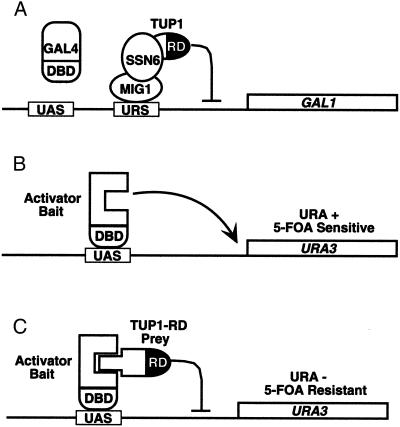

Figure 1.

Rationale for the repressed transactivtor two-hybrid system. (A) Representation of the GAL1 gene in glucose-grown cells, indicating the binding sites for GAL4 (UAS), and MIG1 (URS). MIG1 recruits the general repressors SSN6 and TUP1. The N-terminal RD of TUP1 is indicated in black. (B) Activation of a GAL1-URA3 reporter gene by a GAL4 DBD-activator fusion protein (activator bait) in ura3− yeast gives a URA+ phenotype, and causes sensitivity to 5-FOA. (C) Interaction between a TUP1 RD fusion (TUP1-RD prey) with the activator bait causes repression of transcription, resulting in 5-FOA resistance.

The N-terminal 200 residues of TUP1 are sufficient to cause repression when artificially recruited to a promoter as a LexA fusion (12). Based on this observation, we reasoned that the TUP1 repression domain should function in the context of a two-hybrid system to detect protein interactions with transcriptional activator bait fusions. We show that interaction of GAL4 DBD-activator bait fusion proteins with TUP1 repression domain (RD) prey fusions can be detected by repression of GAL4-dependent reporter gene transcription (see Fig. 1 B and C). We have called this two-hybrid variation the repressed transactivator (RTA) system, and we demonstrate that it is capable of detecting interactions with transcriptional activator proteins in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Yeast Strains.

Wild-type GAL4 was expressed from the ADH1 promoter on the HIS3, 2μ vector pMA210 (13). The deletion derivatives pMA230 (1), pMA242 (1–238∷768–881), pKW2 (1–238∷768–848), pMA246 (1), and pMAB17 (1–147∷B17) were as described (13, 14). Plasmid pJMH105 is a TRP1 2μ vector expressing the TUP1 RD from the ADH1 promoter, which was constructed by cloning an EcoRI/NotI TUP1 fragment, produced by amplification with primers MH50 (5′-GGCGAATTCGTATGACTGCCAGCGTTTCG) and MH51 (5′-GAGCGGCCGCTGCCACGGAAACCTGGGGAGG), into YephalΔlac (15). GAL80 was amplified by using primers MH54 (5′-GAGCGGCCGCTATGGACTACAACAAGAG) and MH55 (5′-GAGCGGCCGCTTATAAACTATAATGCG), and cloned into YEpHAΔlac to create pJMH106 (ADH1-GAL80), or into pJMH105 to create pJMH107 (ADH1-TUP1-GAL80). Plasmid pJMH109 is a LEU2 integrating vector containing a GAL1-URA3 reporter gene, which was constructed by cloning an HindIII/BamHI URA3 fragment, produced by amplification with the primers MH121 (5′-TTCTAAAGCTTATGTCGAAAGCTACATATAAGGAACG) and MH122 (5′-TTATCGGATCCTTAGTTTTGCTGGCCGCATCTTC) into pAOGAL1, which is a LEU2-integrating GAL1 expression plasmid. The pBD plasmids are HIS3, 2μ vectors that express TUP1 repression domain fusions from the MET3 promoter, whereas the pG plasmids are derived from pPHO-GAL4 (16), and express GAL4 DBD fusions from the PHO5 promoter on a TRP1, ARS/CEN backbone. Details of these vectors will be described elsewhere. The pG-Myc (1) transactivation domain was cloned into the SmaI site of pG1 (17) as an XhoI/SmaI fragment (made blunt). The pBD-BIN1 fusion was constructed by inserting a BamHI/BstXI Bin1 cDNA fragment (18) (made blunt) into the SmaI site of pBD2. Plasmid pGAL4-MyoD expressing GAL4-MyoD contains an EcoRI/HindIII DNA fragment consisting of the ADH1 promoter and terminator expressing GAL4 (1) fused to mouse MyoD residues (1), cloned into Ycplac22 (19). Plasmid pRSTE425 expressing TUP1-mouse E12 (residues 274–444) from the PGK promoter/terminator (20), contains a BamHI/BglII E12 DNA fragment fused to the TUP1 RD on pRS425 (21). The TUP1-E12ΔH2 derivative produced from pRSTEΔH2 bears a deletion of E12 residues (376).

Yeast strains were as follows: YJMH1 (MATα, gal4-542, gal80-538, ura3-52, his3-200, ade2-101, ade1, lys2-80, trp1-901, ara1, leu2-3,112, met, LEU2∷GAL1-URA3 (pMH109)); YT6∷171 (MATα, gal4, gal80, ura3, his3, ade2, ade1, lys2, trp1, ara1, leu2, met, URA3∷GAL1-LacZ) (22); W303∷131 [MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, trp1, ura3, can1, URA3∷GAL1-lacZ (pRY131)] (23); H617∷131 [MATα, ade2, can1, his3, leu2, trp1, ura3, srb10∷HIS3, URA3∷GAL1-LACZ (pRY131)] (24); MAV108 (MATa, gal4, gal80, leu2, trp1, his3, SPAL10∷URA3) (25); and Y190 (MATα, ura3-52, leu2-3,112 trp1-901, his3Δ200, ade2-101, gal4, gal80, cyh2R, URA3∷GAL1-lacZ, LYS2∷GAL1-HIS3) (1).

Growth and β-Galactosidase Assays.

Growth assays were performed in strain YJMH1 (GAL4 baits) or MAV108 (GAL4-Myc baits) on synthetic dextrose medium (SD) lacking histidine and tryptophan, containing either 2% galactose and 2% raffinose (GAL/RAF) or 2% glucose (GLU) and 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) where indicated. Cells were suspended in water and normalized to an OD600 = 1.0 and were 10-fold serially diluted in water. Ten microliters of the dilutions were spotted onto selective agar plates and incubated for 3–5 days at 30°C. Cells for β-galactosidase assays were grown in SD to an OD600 = 1.0; activity was measured from extracts prepared by lysis with glass beads (16), and are an average of at least three independent determinations.

Construction of the TUP1-MCF-7 cDNA Fusion Library.

RNA was purified from 5 × 107 exponentially growing MCF-7 cells by using QuickPrep mRNA purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia; catalog no. 27-9254-01) and twice purified on Oligo(dT)-cellulose spin columns. cDNA was synthesized by using the Timesaver cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham Pharmacia; catalog no. 27-9262-01) with modifications to the protocol to produce directional cDNAs. In brief, poly(A)+ RNA was subjected to random primed cDNA synthesis using a specialized direct random hexamer (N6CC). cDNAs were methylated after second strand synthesis, and excess primers were removed in a spin column. Methylated cDNAs were ligated to annealed directional adaptors (AATTCGTCGACGGAT/ATCCGTCGACG). The ligated products were then phosphorylated, digested with BamHI to produce cDNAs with 5′ EcoRI and 3′ BamHI sticky ends, and then ligated into appropriately digested pBD1. Ligated DNA was electroporated into ElectroMAX DH10B electrocompetent cells (GIBCO/BRL, Bethesda; catalog no. 18290-015).

GAL4-VP16AD RTA Screen.

Yeast strain MAV108 bearing plasmid pY1VP16 (26) expressing GAL4-VP16AD (411) was transformed with the pBD-MCF-7 cDNA library and allowed to form colonies on SD lacking histidine and tryptophan. About 6.0 × 106 transformants were scraped, resuspended in 50% glycerol, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. Aliquots were thawed and plated on SD lacking histidine, tryptophan, and methionine and containing 0.1% 5-FOA at a density of 1.2 × 106 colony-forming units per 15-cm plate. Colonies were picked after 5–7 days growth at 30°C, and expanded in liquid SD lacking histidine. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 100 μl of Y-PER (Pierce; catalog no. 78990), and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. DNA was prepared from the lysates by sequential addition of solution II and solution III as with the standard alkaline lysis miniprep protocol (27). cDNA inserts were amplified by PCR using the vector-specific primers oKL1 (5′-TTGCCTGTGGTGTCCTCAAAC) and oKL2 (5′-TGACCAACCTCTGGCGAAG), purified by using QIAquick columns (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA; catalog no. 28106), and sequenced with oKL1. Insert templates for production of in vitro-translated protein were produced by PCR with oligo oIS923 (5′-CCCTCGAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGCCACCATGCAGCAACCACCTCCCCAGGTTTCCGTGGCAG-3′) containing a T7 promoter tag (underlined), and oKL2. [35S]Methionine-labeled in vitro-translated protein was produced by coupled transcription/translation, directly from the PCR template, by using the TNT T7 Quick system (Promega; catalog no. L5540). Interaction of labeled insert-encoded proteins with recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)-VP16 was performed as described previously (28, 29).

Results

The TUP1 N Terminus Represses GAL Transcription When Fused to GAL80.

The N terminus of TUP1 causes repression when fused directly to LexA (12). We examined whether this repression domain was capable of functioning when recruited to DNA by a specific protein–protein interaction as a prey fusion-protein (Fig. 1C). We imagined that such an interaction would mimic the natural function of TUP1, which is normally recruited to specific promoters by DNA-binding proteins as a complex with SSN6 (Fig. 1A). Repression of transcription can be genetically detected by using counterselectable reporter genes such as URA3 (30). Expression of URA3 allows growth of yeast in the absence of uracil (URA+), but also renders them sensitive to 5-FOA, which is converted into a toxic metabolite by the URA3 gene product (Fig. 1B). Repression of URA3 can be detected by the ability to grow in the presence of 5-FOA (Fig. 1C).

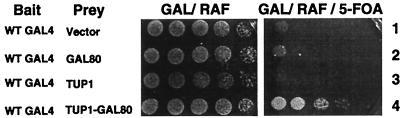

We examined the feasibility of the RTA system by using the well-defined interaction between GAL4 and its regulator GAL80. GAL4 expressed on its own from the ADH1 promoter in a strain bearing a GAL1-URA3 reporter gene causes activation of transcription and renders the yeast sensitive to 5-FOA (Fig. 2, line 1). Expression of GAL80 from the ADH1 promoter in the same strain causes slight inhibition of GAL4, allowing infrequent formation of colonies on 5-FOA (Fig. 2, line 2), but expression of the TUP1 RD on its own has no effect on activation by GAL4 (Fig. 2, line 3). In contrast, coexpression of a TUP1 RD-GAL80 fusion with GAL4 allows growth on 5-FOA (Fig. 2, line 4). We observed this result whether the yeast were grown on glucose- (not shown), or galactose-containing plates (Fig. 2). This result demonstrates that the TUP1 RD inhibits activation by GAL4 when fused to the N terminus of GAL80.

Figure 2.

TUP1-GAL80 represses GAL transcription under inducing conditions. Yeast strain YJMH1 was cotransformed with pMA210 expressing wild-type (WT) GAL4 (bait), and one of the following: pJMH106, expressing GAL80 (line 2); pJMH105, expressing TUP1 RD (line 3); pJMH107, expressing TUP1-GAL80 (line 4); or YephalΔlac (line 1). Equivalent numbers of cells were spotted, in 10-fold serial dilutions (from left to right), onto selective media containing galactose and raffinose without 5-FOA (GAL/RAF), or with 0.1% 5-FOA (GAL/RAF/5-FOA).

SRB10 Is Required for Repression by the N Terminus of TUP1.

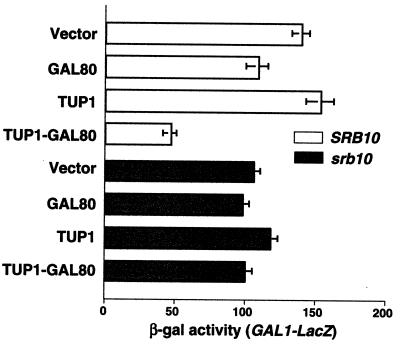

SRB10 has been shown to be required for at least part of the repressive effect of the TUP1 RD in vivo (11, 31). To determine whether the TUP1 RD inhibits transcription by its normal repressive mechanism when fused to GAL80, we examined whether SRB10 was required for repression of GAL4-dependent reporter gene expression by TUP1-GAL80. For these experiments we used a GAL1-lacZ reporter gene (Fig. 3). Consistent with the results of Fig. 2, we found that TUP1-GAL80 inhibited transcriptional activation by GAL4 in wild-type SRB10 yeast (Fig. 3, TUP1-GAL80). GAL80, expressed on its own, caused only slight inhibition of GAL4 (Fig. 3, GAL80), whereas the TUP1 RD had no effect on its own (Fig. 3, TUP1). In contrast, we found that TUP1-GAL80 was incapable of inhibiting activation of GAL1-lacZ reporter gene expression in an srb10 disruption strain (Fig. 3, srb10 TUP1-GAL80). This result supports the conclusion that the TUP1 RD fused to GAL80 causes repression through its normal function, rather than by simply augmenting an inhibitory effect of GAL80.

Figure 3.

Repression of GAL transcription by TUP1-GAL80 requires SRB10. Yeast strains W303:131 (SRB10, open bars), and H617:131 (srb10, black bars) were transformed with a vector control (YephalΔlac) (Vector) or plasmids expressing GAL80 (pJMH106), TUP1 (pJMH105), or TUP1-GAL80 (pJMH107). Yeast was grown to mid-log arithmic phase in selective medium containing galactose, and expression of the GAL1-LacZ reporter gene was assayed by measuring β-galactosidase activity.

Repression of GAL Transcription by TUP1-GAL80 Requires the GAL4 C-Terminal 30 Residues.

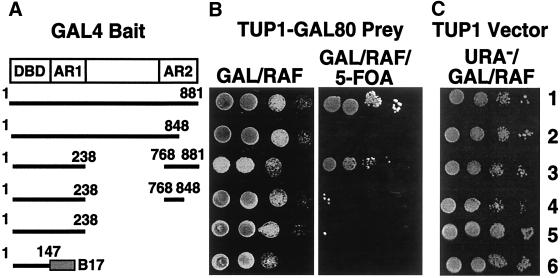

GAL4 contains two regions that activate transcription when fused individually to the DBD, known as activating region 1 and activating region 2 (AR1 and AR2, respectively; see Fig. 4A) (13). AR2 overlaps a region required for interaction with GAL80 (14). Deletion of the C-terminal 30 residues produces a constitutive activator that is incapable of efficient interaction with GAL80 (14). To determine whether repression of transcription by TUP1-GAL80 reflected interaction with the C-terminal 30 residues of GAL4, we examined a series of GAL4 deletion/fusion derivatives. We found that only those GAL4 derivatives bearing the C-terminal 30 residues allowed survival of yeast on 5-FOA when coexpressed with TUP1-GAL80 (Fig. 4B, lines 1 and 3). Thus, yeast expressing GAL4(1–848) coexpressed with TUP1-GAL80 could not grow on 5-FOA (Fig. 4, line 2), indicating that deletion of the C-terminal 30 residues prevents repression of the URA3 reporter. Similarly, a derivative bearing both AR1 and AR2 but lacking the central region [GAL4(1–238∷768–881)] was inhibited by TUP1-GAL80 (Fig. 3, line 3), but a comparable derivative lacking the C-terminal 30 residues was not [GAL4(1–238∷768–848), Fig. 3, line 4]. GAL4 DBD derivatives bearing only AR1 (Fig. 3, line 5), or the B17 activating peptide (32) (Fig. 3, line 6) were also insensitive to inhibition by TUP1-GAL80. When expressed in the absence of TUP1-GAL80, all of the GAL4 derivatives in Fig. 4A activate the GAL1-URA3 reporter gene to allow growth on URA− plates, demonstrating that all of the derivatives are efficient activators (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that repression by TUP1-GAL80 requires the normal site of interaction between GAL4 and GAL80.

Figure 4.

Repression of GAL transcription by TUP1-GAL80 requires the GAL4 C-terminal 30 amino acids. (A) Fusion derivatives and deletions of GAL4. (B) Yeast strain yJMH1 was cotransformed with pJMH107 expressing TUP1-GAL80 and plasmids expressing the GAL4 deletion/fusion derivatives indicated in A. Cells were spotted, in 10-fold serial dilutions (from left to right) on selective plates containing galactose and raffinose without 5-FOA (B, GAL/RAF), or with 0.1% 5-FOA (B, GAL/RAF/5-FOA). (C) Yeast cotransformed with GAL4 expression plasmids (indicated in A) and pJMH105 were spotted as above on minimal selective plates lacking uracil (URA−/GAL/RAF), to assay activation of the GAL1-URA3 reporter.

RTA Detects Interactions with Mammalian Transactivator Proteins.

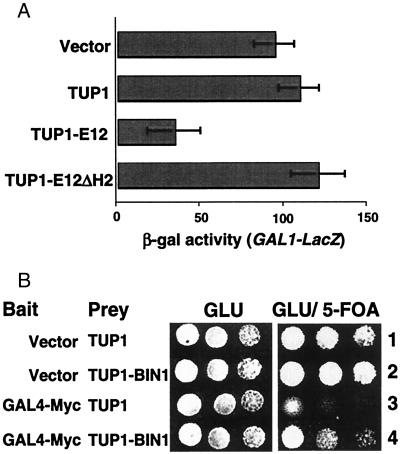

We also examined whether the TUP1 RD could be used to detect interactions with mammalian transactivator bait fusions. MyoD is a basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) family member involved in skeletal muscle development (33). MyoD forms heterodimers with the ubiquitously expressed bHLH protein E12 (34). When expressed in yeast as a fusion to the GAL4 DBD, MyoD causes strong activation of a GAL1-lacZ reporter gene (Fig. 5A). Coexpression of GAL4-MyoD with the TUP1 RD on its own did not affect reporter gene expression (Fig. 5A, TUP1), but coexpression of a TUP1-E12 fusion protein repressed GAL1-lacZ transcription (Fig. 5A, TUP1-E12). In contrast, expression of a TUP1-E12 fusion bearing a deletion of the HLH helix 2, which is known to be required for interaction with MyoD in vitro (35), had no effect on activation by GAL4-MyoD (TUP1-E12ΔH2). Similar to the results presented in Figs. 2 and 4, we also found that coexpression of TUP1-E12 with GAL4-MyoD in yeast bearing a GAL1-URA3 reporter allowed growth on plates containing 5-FOA (not shown). These results demonstrate that the specific interaction between MyoD and E12 can be detected in vivo by using RTA.

Figure 5.

RTA detects interactions with mammalian transactivators. (A) Yeast strain Y190 was cotransformed with pGAL4-MyoD and a vector control (pRS425), pRST425 expressing TUP1-RD, pRSTE425 expressing TUP1-E12, or pRSTE425ΔH2 expressing TUP1-E12 bearing a deletion of helix 2 (TUP1-E12ΔH2). Yeast was grown to mid-log arithmic phase in selective medium containing glucose, and expression of the GAL1-lacZ reporter gene was assayed by measuring β-galactosidase activity. (B) Yeast strain MAV108 was transformed with the bait vector control plasmid (pG1), or pG-Myc(1–262) expressing GAL4-Myc, in combination with the prey vector control plasmid pBD1 (TUP1) or a pBD-BIN expressing TUP1-BIN1. Cells were spotted, in 10-fold serial dilutions (from left to right) on selective plates containing glucose without 5-FOA (GLU), or with 0.05% 5-FOA (GLU/5-FOA).

We also tested interaction between the protooncogene product c-Myc and the putative tumor suppressor protein Bin1, which has been shown to interact with the N-terminal c-Myc transactivation domain (36). The c-Myc N terminus fused to GAL4 DBD causes activation of transcription of GAL4-dependent reporter genes, and causes killing of yeast bearing a GAL1-URA3 reporter gene on 5-FOA (Fig. 5B, line 3). Coexpression of a TUP1 RD-Bin1 fusion with GAL4-Myc allowed survival on 5-FOA (Fig. 5B, line 4), indicating repression of the GAL1-URA3 reporter, and demonstrates specific interaction between c-Myc and Bin1 in vivo.

Identification of VP16-Interacting Proteins by Using RTA.

To determine whether RTA could be used to screen for novel interactions with a transactivator, a cDNA expression library was screened for proteins that interact with the VP16 activation domain. Yeast strain MAV108 (25), bearing a GALUAS-URA3 reporter gene and a GAL4-VP16 expression plasmid, was cotransformed with a TUP1 RD-cDNA fusion expression library. Interacting clones were selected for repression of URA3 by growth on plates containing 0.1% 5-FOA. Sequences were obtained for 30 independent 5-FOA-resistant clones that contained in-frame TUP1-cDNA fusions (Table 1). Multiple isolates were obtained for several of the clones, indicating that the screen may have neared saturation (Table 1). To determine whether any of the clones represented direct interactions with the VP16 activation domain, we assayed in vitro binding of [35S]methionine-labeled insert-encoded protein to recombinant GST and GST-VP16 (data not shown). We found that proteins produced by the BCL7B, HSHZF4, KIAA0710, and TAFII68 inserts interacted specifically with GST-VP16 (Table 1). In contrast, the HSPA5 and DDX5 proteins interacted equally well with GST and GST-VP16, and therefore likely represent nonspecific interactions. The Pol2RA insert-encoded protein did not interact with GST or GST-VP16, indicating that it may represent an indirect interaction with VP16 in vivo. Some of the additional clones may also represent false positives (kynureninase, UDP-glucose dehydrogenase). In summary, these results demonstrate that RTA can be used to screen for novel proteins that interact with transactivators. Our screen using RTA identified specific clones at a proportion comparable to screens using the standard two-hybrid and interaction trap systems.

Table 1.

Identification of VP16-interacting proteins by using RTA

| Sequence | Clones* | In vitro† | Function/notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bA155N3.1 | 4 | I | Novel protein similar to KIAA0694 | 37 |

| BCL7B | 3 | + | Rearranged in B cell lymphoma, novel conserved gene family | 38 |

| DDX5 | 1 | NS | DEAD-box helicase, 68 kDa | 39 |

| HSHZF4 | 1 | + | Krüppel-related zinc finger protein | 40 |

| KIAA0710 | 1 | + | Unknown function | 37 |

| Pol2RA | 1 | − | RNA polymerase II 220-kDa α-subunit | 41 |

| hSAN | 1 | I | Similar to Drosophila melanogaster separation anxiety protein, AK023256 | |

| TAFII68 | 1 | + | 68-kDa TBP-associated factor | 42 |

| 28S | 1 | ND | 28S Ribosomal RNA | |

| HSPA5 | 2 | NS | BiP heat shock protein | 43 |

| Kynureninase | 1 | ND | l-Kynurenine hydrolase | 44 |

| UGDH | 1 | ND | UDP-glucose dehydrogenase | 45 |

| ESTs | 3 | ND | Uncharacterized EST sequences | |

| Unannotated | 9 | ND | Sequences from unannotated genomic DNA |

BiP, immunoglobulin light chain binding protein; EST, expressed sequence tag.

Number of independent isolates.

I, inconclusive; +, in vitro interaction; −, no in vitro interaction; NS, nonspecific in vitro interaction; ND, not determined.

Discussion

We demonstrate that the repression domain of TUP1 can function when recruited to promoters by specific interactions between fusion proteins. The TUP1 RD fused to GAL80 causes repression of GAL4-dependent reporter genes. Repression by TUP1-GAL80 requires the C-terminal 30 residues of GAL4, which are known to interact with GAL80 in vitro, and are necessary for normal inhibition by GAL80 in vivo. Furthermore, repression by TUP-GAL80 requires SRB10, indicating that the TUP1 RD inhibits transcription through its normal function in the context of the two-hybrid interaction. We show that this property of the TUP1 RD can be exploited for detecting interactions with transactivator proteins in vivo. Protein interactions with two different mammalian transcription factors, MyoD and c-Myc, were detected by using RTA. We have also performed a pilot scale two-hybrid screen using GAL4-VP16 as a bait to identify several interacting proteins not previously described. These results demonstrate the usefulness of RTA for characterizing interactions with transactivators in vivo.

Proteins that normally function to activate transcription, or proteins that artificially activate when fused to a DBD, cannot be used as baits in the standard two-hybrid or interaction-trap systems unless the regions that cause activation are deleted. This problem needed to be addressed because critical interactions between transcription factors and their regulators are often mediated by the same regions that cause transcriptional activation. This is illustrated in the results presented here. Interaction of GAL80 with GAL4 requires the C-terminal 30 residues of GAL4. This region is also necessary for efficient activation of transcription, and is known to contact several general initiation factors (28, 46). In addition, interaction between the putative tumor suppressor protein Bin1 requires the N-terminal transactivation domain of c-Myc (47). Our experiments demonstrate that the RTA system is useful for genetically detecting interactions with transactivation domains. However, the assay is not dependent on direct interaction of the TUP1-prey fusion with the activation domain of the activator bait, because we also demonstrate interaction between MyoD and its heterodimer partner E12. This interaction occurs through helix 2 of the bHLH motif (48), which is not directly responsible for transactivation.

In our screen with GAL4-VP16 as a bait fusion, we identified several previously undescribed interacting proteins, including BCL7B, HZF4, and TAFII68. These appear to be direct interactions, as protein produced by in vitro transcription/translation of the cDNA inserts bound GST-VP16 in pull-down assays (data not shown, and Table 1). The significance of these interactions for activation by VP16, or replication of HSV-1, will require confirmation and characterization of the interactions in vivo. Interaction of an activator with TAFII68 has not been demonstrated previously, although several viral activators are known to interact with TAFII250 (49–51), and TAFII40 (52). Surprisingly, in our screen, we did not identify general transcription factors (GTFs) that are known transcriptional activation targets for VP16 in vitro (52–55). It is possible that these interactions are too weak to be identified at the 5-FOA concentration used, or some TUP1-GTF fusions may be toxic in yeast due to nonspecific recruitment to promoters. One clone representing the largest RNA polymerase II subunit (Pol2RA) was recovered in the screen, but we did not detect interaction of the protein with VP16 in vitro (not shown). This result indicates that, as with the standard two-hybrid and interaction-trap systems, some interactions between the bait and prey fusions in RTA may be mediated through complexes with one or more yeast proteins.

Several other two-hybrid systems can be used with bait proteins that activate transcription. The Sos- and Ras-recruitment two-hybrid strategies rely on interaction between the bait and prey fusions for recruitment of CDC25 or Ras to the plasma membrane, allowing growth at the nonpermissive temperatures in cdc25 or ras temperature-sensitive strains (56, 57). Additionally, an RNA polymerase III-based system has been developed that utilizes the activating protein τ138 (58). The advantage of RTA over these strategies is that interactions with transactivator baits can be assayed in the context of their normal function—when they are localized to the nucleus, bound to a promoter, and activating RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription. We expect that the RTA system will be useful for characterizing interactions between transcriptional activator proteins and their regulatory molecules and coactivators, as well as identifying novel interactions involved in transcriptional regulation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and National Cancer Institute of Canada with funds from the Canadian Cancer Society.

Abbreviations

- RTA

repressed transactivator assay

- RD

repression domain

- AD

activation domain

- DBD

DNA-binding domain

- 5-FOA

5-fluoroorotic acid

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Fields S, Song O. Nature (London) 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golemis E, Gyuris J, Brent R. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 13. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 20.1.1–2.1.40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brent R, Ptashne M. Cell. 1985;43:729–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nehlin J O, Carlberg M, Ronne H. EMBO J. 1991;10:3373–3377. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bu Y, Schmidt M C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1002–1009. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper J P, Roth S Y, Simpson R T. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1400–1410. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frolova E, Johnston M, Majors J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1350–1358. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.5.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gavin I M, Simpson R T. EMBO J. 1997;16:6263–6271. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmondson D G, Smith M M, Roth S Y. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1247–1259. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang L, Zhang W, Roth S Y. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6555–6562. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuchin S, Carlson M. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1163–1171. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzamarias D, Struhl K. Nature (London) 1994;369:758–761. doi: 10.1038/369758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J, Ptashne M. Cell. 1987;48:847–853. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma J, Ptashne M. Cell. 1987;50:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90670-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung W, Olson K A, Breitkreutz A, Sadowski I. Eur J Biochem. 1997;245:241–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone G, Sadowski I. EMBO J. 1993;12:1375–1385. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato J G, Barrett J, Villa-Garcia M, Dang C V. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5914–5920. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wechsler-Reya R, Sakamuro D, Zhang J, Duhadaway J, Prendergast G C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31453–31458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gietz R D, Sugino A. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masuda Y, Park S M, Ohkuma M, Ohta A, Takagi M. Curr Genet. 1994;5:412–417. doi: 10.1007/BF00351779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christianson T W, Sikorski R S, Dante M, Shero J H, Hieter P. Gene. 1992;110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadowski I, Niedbala D, Wood K, Ptashne M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10510–10514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas B J, Rothstein R. Cell. 1989;56:619–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balciunas D, Ronne H. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4421–4425. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vidal M, Brachmann R K, Fattaey A, Harlow E, Boeke J D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10315–10320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadowski I, Bell B, Broad P, Hollis M. Gene. 1992;118:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90261-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birnboim H C. Methods Enzymol. 1983;100:243–255. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melcher K, Johnston S A. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2839–2848. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barlev N A, Candau R, Wang L, Darpino P, Silverman N, Berger S L. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19337–19344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boeke J D, Trueheart J, Natsoulis G, Fink G R. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:164–175. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee M, Chatterjee S, Struhl K. Genetics. 2000;155:1535–1542. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma J, Ptashne M. Cell. 1987;51:113–119. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Megeney L A, Rudnicki M A. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:723–732. doi: 10.1139/o95-080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czernik P J, Peterson C A, Hurlburt B K. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9141–9149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.9141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murre C, McCaw P S, Vaessin H, Caudy M, Jan L Y, Jan Y N, Cabrera C V, Buskin J N, Hauschka S D, Lassar A B, et al. Cell. 1989;58:537–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakamuro D, Elliott K J, Wechsler-Reya R, Prendergast G C. Nat Genet. 1996;14:69–77. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishikawa K, Nagase T, Suyama M, Miyajima N, Tanaka A, Kotani H, Nomura N, Ohara O. DNA Res. 1998;5:169–176. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.3.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jadayel D M, Osborne L R, Coignet L J, Zani V J, Tsui L C, Scherer S W, Dyer M J. Gene. 1998;224:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossler O G, Hloch P, Schutz N, Weitzenegger T, Stahl H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:932–939. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.4.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abrink M, Aveskogh M, Hellman L. DNA Cell Biol. 1995;14:125–136. doi: 10.1089/dna.1995.14.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho K W, Khalili K, Zandomeni R, Weinmann R. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:15204–15210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertolotti A, Lutz Y, Heard D J, Chambon P, Tora L. EMBO J. 1996;15:5022–5031. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koh S S, Ansari A Z, Ptashne M, Young R A. Mol Cell. 1998;1:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elliott K, Sakamuro D, Basu A, Du W, Wunner W, Staller P, Gaubatz S, Zhang H, Prochownik E, Eilers M, Prendergast G C. Oncogene. 1999;18:3564–3573. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirakata M, Paterson B M. EMBO J. 1995;14:1766–1772. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carrozza M J, DeLuca N A. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3085–3093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geisberg J V, Chen J L, Ricciardi R P. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6283–6290. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weissman J D, Brown J A, Howcroft T K, Hwang J, Chawla A, Roche P A, Schiltz L, Nakatani Y, Singer D S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11601–11606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodrich J A, Hoey T, Thut C J, Admon A, Tjian R. Cell. 1993;75:519–530. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao H, Pearson A, Coulombe B, Truant R, Zhang S, Regier J L, Triezenberg S J, Reinberg D, Flores O, Ingles C J, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7013–7024. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.7013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin Y S, Ha I, Maldonado E, Reinberg D, Green M R. Nature (London) 1991;353:569–571. doi: 10.1038/353569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobayashi N, Horn P J, Sullivan S M, Triezenberg S J, Boyer T G, Berk A J. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4023–4031. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Broder Y C, Katz S, Aronheim A. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1121–1124. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aronheim A, Zandi E, Hennemann H, Elledge S J, Karin M. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3094–3102. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marsolier M C, Prioleau M N, Sentenac A. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:243–249. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]