Abstract

The effect of plant invasion on the microorganisms of soil sediments is very important for estuary ecology. The community structures of methanogens and sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) as a function of Spartina alterniflora invasion in Phragmites australis-vegetated sediments of the Dongtan wetland in the Yangtze River estuary, China, were investigated using 454 pyrosequencing and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) of the methyl coenzyme M reductase A (mcrA) and dissimilatory sulfite-reductase (dsrB) genes. Sediment samples were collected from two replicate locations, and each location included three sampling stands each covered by monocultures of P. australis, S. alterniflora and both plants (transition stands), respectively. qPCR analysis revealed higher copy numbers of mcrA genes in sediments from S. alterniflora stands than P. australis stands (5- and 7.5-fold more in the spring and summer, respectively), which is consistent with the higher methane flux rates measured in the S. alterniflora stands (up to 8.01 ± 5.61 mg m−2 h−1). Similar trends were observed for SRB, and they were up to two orders of magnitude higher than the methanogens. Diversity indices indicated a lower diversity of methanogens in the S. alterniflora stands than the P. australis stands. In contrast, insignificant variations were observed in the diversity of SRB with the invasion. Although Methanomicrobiales and Methanococcales, the hydrogenotrophic methanogens, dominated in the salt marsh, Methanomicrobiales displayed a slight increase with the invasion and growth of S. alterniflora, whereas the later responded differently. Methanosarcina, the metabolically diverse methanogens, did not vary with the invasion of, but Methanosaeta, the exclusive acetate utilizers, appeared to increase with S. alterniflora invasion. In SRB, sequences closely related to the families Desulfobacteraceae and Desulfobulbaceae dominated in the salt marsh, although they displayed minimal changes with the S. alterniflora invasion. Approximately 11.3 ± 5.1% of the dsrB gene sequences formed a novel cluster that was reduced upon the invasion. The results showed that in the sediments of tidal salt marsh where S. alterniflora displaced P. australis, the abundances of methanogens and SRB increased, but the community composition of methanogens appeared to be influenced more than did the SRB.

Keywords: dissimilatory sulfite reductase B (dsrB), methyl coenzyme M reductase A (mcrA), spartina alterniflora, phragmites australis, estuarine marsh

Introduction

Estuarine wetlands are among the most productive ecosystems on the Earth and provide many key ecosystem services. These environments are highly vulnerable to the invasion of exotic plant species, and ecosystem functions may be altered as a consequence of the invasion (Williams and Grosholz, 2008). For example, the native Phragmites australis and Scirpus mariqueter communities of the Dongtan tidal flats, comprising approximately 32,600 ha of the Yangtze River estuary, are currently being invaded by the aggressive exotic Spartina alterniflora. Furthermore, S. alterniflora was introduced to the Yangtze River estuary in 1990s to increase the protection of coastal banks and to accelerate sedimentation and land formation (Chung, 1993; Liao et al., 2007). However, due to its extensive expansion (approximately 43% of the vegetated part as of 2004) (Chen et al., 2008) and displacement of the native species, a number of ecological impacts have occurred. The impacts of S. alterniflora invasion on the aboveground flora and fauna of Dongtan tidal salt marsh have been described by several studies (Jiang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010). Recently, a study by Cheng and his colleagues (2007) demonstrated that methane flux rates in S. alterniflora stands are higher than in areas dominated by P. australis, which is consistent with several studies that indicate higher methane flux rates in the stands covered by S. alterniflora than in those covered by other salt marsh plants (Cheng et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2012). The root exudates and litter decomposition of S. alterniflora can alter the nutritional contents of soils, which in turn may affect the functioning of soil microbial communities. Hence, parallel to the impacts that S. alterniflora may pose to the aboveground ecology, it has the potential to affect belowground microbial communities and processes. In tidal marshes of estuaries where large amounts of vegetation and river-derived organic matter are deposited, nutrients are typically mineralized through anaerobic processes, predominantly via methanogenesis and sulfate reduction.

Methanogenesis and dissimilatory sulfate reduction are the two key terminal electron-scavenging processes in the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter. These anaerobic processes are known to compete for hydrogen and acetate (Abram and Nedwell, 1978; King, 1984), but the latter has higher affinity and can outcompete with methanogenesis in sediments having high sulfate concentration, such as marine and salt marsh surface sediments (Oremland et al., 1982; Winfrey and Ward, 1983; Purdy et al., 2003). Although competition is one of the major factors controlling the distribution and activity of methanogenesis, land and tide-derived depositions and autochthonous production by marsh plants and freshwater dilutions of sea water in tidal marshes may create conditions for methanogenesis to be a major terminal electron accepting process (Senior et al., 1982; Schubauer and Hopkinson, 1984; Holmer and Kristensen, 1994; Kaku et al., 2005). As the type of marsh plants may determine the availability and level of nutrients in sediments and, hence, microbial activities (Andersen and Hargrave, 1984; Ravit et al., 2003; Hawkes et al., 2005; Batten et al., 2006), the structure and function of methanogens and SRB in salt marshes may be influenced by the invasion and displacement of native plants by exotic species.

Methanogens are strictly anaerobic microorganisms. They are composed of six well-established archaeal orders: Methanobacteriales, Methanococcales, Methanomicrobiales, Methanosarcinales, Methanocellales, and Methanopyrales. Moreover, recent culture independent techniques have discovered novel methanogen members such as Zoige cluster-I (ZC-I) (Zhang et al., 2008) and the anaerobic methanotrophs (ANME-1, 2 and 3) (Knittel et al., 2005). Most methanogens are hydrogenotrophic, utilizing carbon dioxide as a source of carbon and hydrogen or formate as electron sources. However, members of the genus Methanosarcina are physiologically versatile, additionally utilizing acetate and methylated compounds such as methanol, monomethylamine, dimethylamine and trimethylamine, whereas genus Methanosaeta is restricted to acetate (Liu and Whitman, 2008). Similarly, sulfate-reducing microbes are strictly anaerobic microorganisms. They reduce sulfate to sulfide using several substrates such as hydrogen, formate, acetate, butyrate, propionate and ethanol as electron sources (Barton and Fauque, 2009). These microbes are found within several phylogenetic lines: in the class Deltaproteobacteria (Desulfobacterales, Desulfovibrionales, and Syntrophobacterales), phylum Firmicutes (Desulfotomaculum, Desulfosporomusa, and Desulfosporosinus), phylum Nitrospirae (Thermodesulfovibrio), phylum Thermodesulfobacteria and archaeal genera (Archaeoglobus, Thermocladium, and Caldivirga). Diverse phylogenetic lines generally present major challenges to specifically targeting these organisms in environmental samples using the universal 16S rRNA gene as a marker. Therefore, targeting group-specific functional genes, such as those encoding methyl coenzyme M reductase A (mcrA) and dissimilatory sulfite reductase (dsrB), are commonly used as alternatives to the 16S rRNA gene to investigate methanogens and SRB, respectively (Luton et al., 2002; Dar et al., 2006; Geets et al., 2006).

In this study, 454 pyrosequencing and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) were used to investigate the diversity and abundance of methanogens and SRB in the sediments vegetated by P. australis, S. alterniflora and transition stands where both plants are available. Investigations were conducted in two seasons: before growth (April) and during the full growth stage (August).

Materials and methods

Sampling and in situ measurements

This study was conducted in the tidal salt marsh of Dongtan, where the intentionally introduced S. alterniflora is aggressively displacing the native P. australis. Two replicate sampling locations (approximately 60 m apart) were selected, each with three distinct sampling stands (approximately 20 m apart) covered by monocultures of P. australis (non-invaded), transition stands (both plants available) and S. alterniflora (completely displaced). Investigations were conducted in two seasons: before growth (April) and at full growth stage (August). In both sampling seasons, the methane and carbon dioxide flux rates were determined from each location by collecting the gases using the enclosed static chamber technique (Hirota et al., 2004) and gas chromatographic analysis using a 6890N gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Ltd. USA).

Soil temperatures and conductivities were directly measured using a Field Scout™ direct soil EC meter with a jab probe (2265FS, USA), whereas pH was measured using a IQ150 portable pH meter (IQ Scientific Instruments, USA). From each sampling stand, five replicate sediment samples (surface to 5 cm) were collected within a radius of approximately 2 m. Soil samples were immediately sealed in polyethylene bags and transported to the laboratory on ice. Within one hour of collection, replicate samples were homogenized and stored at −20°C for downstream analyses.

Sediment samples for chemical analysis were dried completely in an oven at 50°C. Then, all non-decomposed plant litter and root materials were removed easily from the gently crushed sediments. The sediments were then ground into powder and passed through #10 meshes where part of the powder was used for determination of total carbon and total nitrogen using an NC analyzer (FlashEA1112 Series, Thermo Inc., Italy), and the remainder was used for analysis of sulfate ions using an ion chromatograph (ICS-1000; Dionex, USA).

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

The total genomic DNA of each sample was extracted in duplicate tubes from 0.25 g of sediment (wet weight) using a PowerSoil DNA Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Amplicons for 454 pyrosequencing were prepared following the 2-step barcoded PCR method (Berry et al., 2011). In the first-step PCR, the 50 μl reaction contained 2 μl of template DNA (5–10 ng), 25 μl of Taq PCR Master Mix (TianGen, China), 2 μl (10 μM) of each primer (Table 1), 2 μl of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (0.8 μg ul−1 final concentration) and 17 μl of distilled water. Amplifications were conducted in a thermal cycler (PCR Thermal Cycler Dice; Takara, Japan) for 25 cycles. For the second-step PCR, the forward and reverse primers were modified as follows: 5′-Adapter A + 8 bp barcode + TC + forward primer—3′ and 5′-Adapter B + CA + reverse primer −3′, respectively. Whereas Adaptor A and B represent the 30 bp that were used as sequencing primers, the 8-bp barcode sequences were used to identify individual samples, and TC and CA were used as linkers. For each sample, 2 μl of the first-step PCR product was used as template DNA in the second-step PCR. Except for the annealing temperatures, which were raised by 2°C, all the PCR conditions were the same in the second-step PCR as in the first-step PCR. Amplifications were conducted for 10 cycles. The PCR products were then purified using the UltraClean PCR Clean-Up kit (MoBio, USA) and then quantified using the PicoGreen reagent (Invitrogen, USA) for dsDNA on a ND3300 Fluorospectrometer (NanoDrop Technologies, USA). Lastly, the amplicons of all samples were pooled in an equivalent concentration for 454 pyrosequencing. Pyrosequencing was conducted using a Roche/454 (GS FLX Titanium System). For 454 pyrosequencing, the barcoded and pooled amplicons were rechecked for the absence of primer dimers, and emulsion PCR was set up according to Roche's protocols.

Table 1.

Primers used for pyrosequencing and/or qPCR.

| Primer | Sequence (5′ – 3′)a | Target | Ta (°C) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mlas | GGTGGTGTMGGDTTCACMCARTA | mcrA gene | 55 | Steinberg and Regan, 2008 |

| mcrA-rev | CGTTCATBGCGTAGTTVGGRTAGT | |||

| DSRp2060F | CAACATCGTYCAYACCCAGGG | dsrB gene | 53 | Dar et al., 2006; Geets et al., 2006 |

| Dsr-4Rdeg | GTGTARCAGTTDCCRCA | |||

| 27f | AGAGTTGATYMTGGCTCAG | Bacterial 16S rDNA (for pyrosequencing) | 52 | Giovannoni et al., 1988 |

| 536r | GTATTACCGCGGCKGCTG | |||

| 338f | ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGC | Bacterial 16S rDNA (for qPCR) | 52 | Giovannoni, 1991 |

| 536r | GTATTACCGCGGCKGCTG | |||

| Arch340F | CCCTAYGGGGYGCASCAG | Archaeal 16S rDNA | 57 | Gantner et al., 2011 |

| Arch1000R | GAGARGWRGTGCATGGCC |

M, A/C; D, A/G/T; R, A/G; B, C/G/T; V, A/C/G; Y, C/T; K, G/T; S, G/C; W, A/T.

Quantitative real-time PCR

SYBR Green I-based qPCR was conducted for both the 16S rRNA gene (bacteria and archaea) and functional genes (mcrA and dsrB) using the primers presented in Table 1. The coverage and specificity of the functional gene primers were validated through clone library construction before application to qPCR. The reaction mixes were prepared as previously described (Zeleke et al., 2013), and triplicate reaction tubes were used for each sample. Known copy numbers of linearized plasmid DNA with the respective gene inserted from pure clones were used as standards for the quantifications. The linearization of the plasmid DNA of each gene was performed using the EcoRI restriction enzyme (Fermentas, USA) following the recommended protocol. The amplification efficiency and R2 values were between 90–99% and 0.98–1, respectively. qPCR of all genes were conducted using a MX3000P QPCR thermocycler (Stratagene, USA). The annealing temperatures are described in Table 1. Melting curves were analyzed to detect the presence of primer dimers. The results were analyzed using MxPro QPCR software version 3.0 (Stratagene, USA).

Data analysis

The raw 454 pyrosequencing data of the 16S rRNA and functional genes were trimmed using the sample-specific barcodes, in which the forward primers and sequences with ambiguous nucleotides were removed. For the functional genes, BLASTx analyses were performed against the known sequences of the NCBI database. The sequences that did not match the target gene were excluded from further analysis. The remaining sequences were translated by the RDP's functional gene and repository FrameBot tool (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu/FunGenePipeline/framebot/form.spr), which detects and corrects the likely frameshift errors. After removing amino acid sequences with stop codons and/or unknown amino acids, the remaining sequences were aligned by the RDP's functional gene and repository aligner tool. A few (0.5–1%) poorly aligned amino acid sequences were also removed, and the names of the remaining quality amino acid sequences were used to recover the corresponding original nucleotide sequences using Mothur software, version 1.8 (Schloss et al., 2009). Moreover, potential chimeric sequences were also removed (<1%) using the chimra.uchime command in Mothur (Schloss et al., 2009). The final quality nucleotide sequences were used to define operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and downstream analyses. Before calculating the diversity indices, the sequence numbers of each sample were normalized to an equal number. Sequence information was also used for principal component analysis (PCA) using the UniFrac online tool (http://bmf.colorado.edu/unifrac/). For 16S rRNA genes of the total bacteria and archaea, raw data sequences were treated through the Mothur program (Schloss et al., 2009). Briefly, after trimming, pre-clustering and removing the potential chimeric sequences, the remaining purified sequences were used for phylogenetic affiliation, which was performed through BLAST analysis against the Silva taxonomy files at an 80% threshold value.

Sequence accession numbers

All the mcrA, dsrB and 16S rRNA genes of the total bacterial and archaeal sequences recovered from the estuarine marsh of Dongtan were deposited in the NCBI's sequence read archives with the accession numbers of SRP021055, SRP021326, SRP021327 and SRP021329, respectively.

Results

Methane flux rates and sediment characteristics

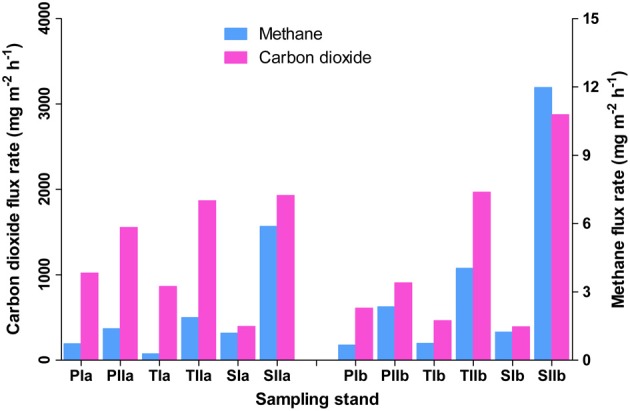

Methane flux rates differed both with the invasion and growth of S. alterniflora (Figure 1). In spring, the mean flux rates in the P. australis, transition, and S. alterniflora stands were approximately 0.51 ± 0.31, 0.93 ± 0.37, and 0.99 ± 0.35 mg m−2 h−1, respectively. This indicates an approximately 97% increase of flux rate with S. alterniflora invasion. When the plants were fully grown, these flux rates were increased to 1.63 ± 0.34, 4.11 ± 2.49, and 8.01 ± 5.61 mg m−2 h−1, respectively, in the P. australis, transition and S. alterniflora stands and the impact of S. alterniflora was significant in the summer (152 and 391% higher in the transition and S. alterniflora strands, respectively, than in P. australis stands). The gas flux rates also displayed significant increases in the summer (225, 343, and 709% in the P. australis, transition and S. alterniflora stands, respectively). These increases were positively correlated with the change in temperatures (R2 = 0.2, α = 0.05), although not significant. Similarly, carbon dioxide flux rates were relatively high in the S. alterniflora stands. When the mean flux ratios of methane to carbon dioxide were compared, higher values were observed in the S. alterniflora stands than in the P. australis stands. In spring, the ratios were approximately 9 × 10−4 and 3 × 10−3, in the P. australis and S. alterniflora stands, respectively, representing an approximate 3.5-fold increase in the S. alterniflora stands (Figure 1). In summer, these ratios were approximately 1.74 × 10−3 and 3.6 × 10−3, in the P. australis and S. alterniflora stands, respectively, representing an increase of approximately 2.1-fold in the S. alterniflora stands.

Figure 1.

Methane and carbon dioxide flux rates in the P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands in the Dongtan salt marsh located in the Yangtze River estuary. In the sample names, I and II represent the spring and summer samples, respectively, whereas “a” and “b” indicate the replicate locations.

As expected, soil temperature, pH, conductivity and sulfate levels did not vary across the sampling stands (Table 2). However, there was a marked increase in the mean soil temperature from spring to summer (from approximately 15—28°C). In both seasons, the total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) levels of sediments were higher in the S. alterniflora-influenced sediments than the P. australis sediments. However, minor reductions of TC and TN were observed in all stands during the summer (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of sediments from P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands in the Dongtan salt marsh in the Yangtze estuary.

| Sample | pH | Temperature (°C) | Conductivity (mS) | Sulfate (mg kg −1) | TC (% of dry soil) | TN (% of dry soil) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Spring | Summer | Spring | Summer | Spring | Summer | Spring | Summer | Spring | Summer | |

| Pa | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 15.4 ± 0.9 | 27.9 ± 0.1 | ND | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 242.4 | 272.2 | 2.1 | 2 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Pb | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 14.8 ± 0.2 | 28.1 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 224.7 | 275.4 | 2.4 | 2 | 0.21 | 0.14 |

| Ta | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 15.9 ± 0.4 | 27.5 ± 0.2 | ND | 8.2 ± 1.1 | 287.3 | 331 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Tb | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 7.3 ± 0.4 | 16.3 ± 0.3 | 28.1 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 7.7 ± 0.5 | 245.3 | 254.7 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Sa | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 15.5 ± 0.4 | 27.8 ± 0.2 | ND | 9.4 ± 0.7 | 263.4 | 331.8 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 0.25 | 0.23 |

| Sb | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.4 | 13.5 ± 0.4 | 27.9 ± 0.1 | 8.2 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 0.3 | 326.6 | 325 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

In the sample names, ‘a’ and ‘b’ represent the replicate sampling locations.

Values given for pH, temperature and conductivity are the means ± standard deviations of 5 replicate measurements, but sulfate was measured once (from the mixed samples) in the lab. ND, not determined.

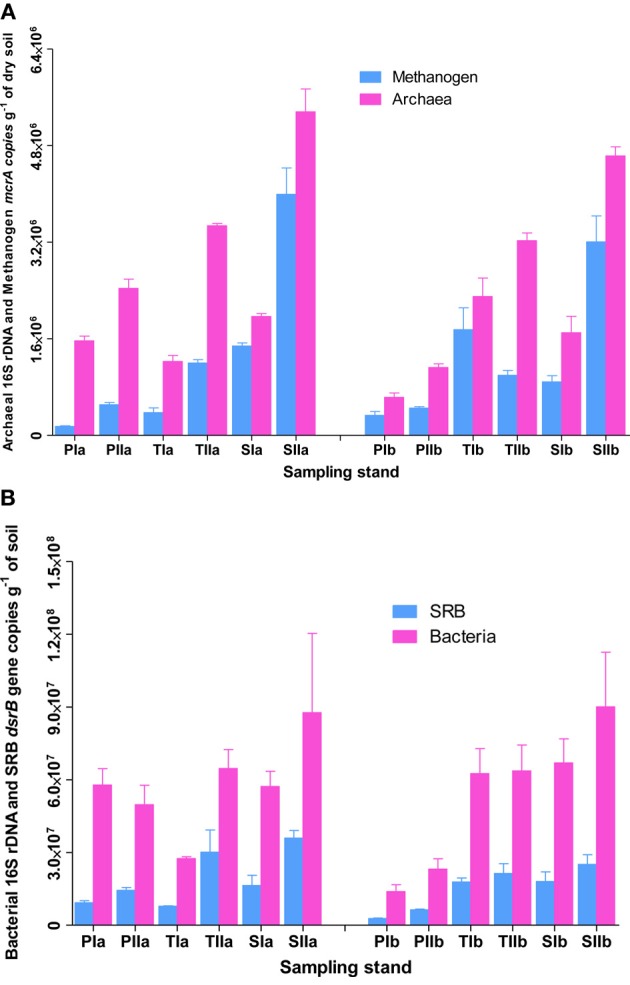

Abundances of methanogens and SRB

To understand the overall relative abundances of methanogens and SRB, SYBR Green I-based quantification of total archaeal and bacterial 16S rRNA genes were determined from the samples used to investigate methanogens and SRB. As revealed from the copy numbers of mcrA and dsrB genes, the abundances of methanogens and SRB varied with the invasion and growth of S. alterniflora (Figures 2A,B). In spring, the mean abundance of methanogens were approximately 2.4 ± 1.3 × 105, 1.1 ± 0.9 × 106 and 1.2 ± 0.4 × 106 copies per g of dried soil in the P. australis, transition and S. alterniflora stands, respectively, indicating there were approximately 5 times more methanogens in the S. alterniflora stands than in the P. australis stands. Furthermore, higher abundances of methanogens were observed in the summer (4.8 ± 0.1 × 105, 1.2 ± 0.1 × 106 and 3.6 ± 0.6 × 106 copies per g of dried soil in the P. australis, transition and S. alterniflora stands, respectively), representing a dramatic increase of methanogens in the S. alterniflora stands (approximately 7.5-fold higher than the P. australis stands). In terms of the changes associated with S. alterniflora invasion, similar trends were observed for the abundance of archaeal 16S rRNA gene copies in both sampling seasons (Figure 2A). The mean abundance proportions of methanogens (copies of mcrA to 16S rRNA gene of total archaea) were also higher in the S. alterniflora-impacted stands than in the P. australis stands. In the spring, the mean abundance proportions of methanogens were approximately 31, 53, and 63% in the P. australis, transition and S. alterniflora stands, respectively, whereas they slightly changed to 30, 32 and 71%, respectively, in the summer.

Figure 2.

Abundance of (A) methanogens and (B) SRB in sediments from P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands of the Dongtan salt marsh located in the Yangtze River estuary. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicate reaction tubes. The sample names are as described in Figure 1.

Similarly, the invasion and growth of S. alterniflora increased the abundance of SRB in both sampling seasons (Figure 2B). In the spring, the mean abundances of SRB were approximately 5.99 ± 4.06 × 106, 1.28 ± 0.71 × 107, and 1.72 ± 0.12 × 107 per g of dried soil, respectively, for P. australis, transition and S. alterniflora stands, indicating 2.2- and 2.9-times more copies in the transition and S. alterniflora stands than in the P. australis stands, respectively. Although the abundance of SRB was greater than that of the methanogens (up to 2 orders of magnitude), the increases in the mean abundances of SRB associated with S. alterniflora invasion in the summer were relatively lower (approximately 3.0-fold lower than the abundances in the spring). When compared with the total bacterial abundance, the mean abundance proportions of the SRB ranged from 17 to 34%. Unlike most of the sediment characteristics measured at the salt marsh, TC was positively correlated with the abundance of methanogens (R2 = 0.54, α = 0.05) and SRB (R2 = 0.70, α = 0.05).

Methanogens and SRB diversity

Purified mcrA sequences were used to define OTUs at the genus (89% similarity cutoff) and family (79% similarity cutoff) levels (Steinberg and Regan, 2008). At the genus level, maximum numbers of mcrA OTUs were observed in sediments collected from P. australis stands, whereas the minimum numbers were observed in sediments from S. alterniflora stands (Table 3). Rarefaction curves at both similarity cutoffs leveled off horizontally between 30 and 58 OTUs (data not shown here), indicating the use of acceptable numbers of sequences for good representation of the methanogen communities from the study site. Despite the greater abundance of methanogens in the S. alterniflora stands of both sampling seasons (Figure 2A), richness and diversity indices (Chao1, ACE and Shannon) indicated lower diversity and richness of methanogens in the S. alterniflora stands compared with the P. australis stands (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of the diversity indices of mcrA genes amplified from sediment samples of the S. alterniflora (S), transition (T) and P. australis (P) stands.

| Season | Sample | NSa | 89% Similarity cutoff | 79% Similarity cutoff | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOb | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | NOb | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | |||

| Spring | PIa | 162 | 58 | 128 | 188 | 3.6 | 33 | 46 | 65 | 2.8 |

| PIb | 176 | 39 | 65 | 115 | 2.6 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 2 | |

| TIa | 504 | 39 | 58 | 82 | 2.5 | 22 | 31 | 39 | 1.9 | |

| TIb | 479 | 32 | 56 | 60 | 2.3 | 20 | 33 | 41 | 1.7 | |

| SIa | 1455 | 33 | 60 | 61 | 2.4 | 21 | 30 | 32 | 1.8 | |

| SIb | 1035 | 25 | 51 | 148 | 2 | 20 | 31 | 33 | 1.6 | |

| Summer | PIIa | 493 | 50 | 95 | 182 | 3.3 | 36 | 113 | 163 | 2.7 |

| PIIb | 319 | 50 | 347 | 371 | 3.2 | 26 | 61 | 111 | 2.3 | |

| TIIa | 598 | 34 | 111 | 130 | 2.5 | 26 | 44 | 72 | 2.1 | |

| TIIb | 516 | 35 | 50 | 96 | 2.7 | 22 | 31 | 41 | 2.1 | |

| SIIa | 763 | 35 | 98 | 97 | 2.7 | 20 | 56 | 41 | 2.1 | |

| SIIb | 586 | 41 | 96 | 93 | 2.9 | 26 | 37 | 68 | 2.3 | |

The diversity indices were calculated at 89 and 79% similarity cutoffs using normalized sequence numbers. The sample names are as described in Figure 1.

NSa, number of sequences; NOb, number of OTUs.

However, dsrB OTUs were defined at three sequence similarity cutoffs (90, 80, and 70%). Unlike mcrA, significantly large numbers of dsrB OTUs were observed at 90 and 80% similarity cutoffs (Table 4). At the 70% similarity cutoff, the numbers of OTUs were reduced by more than half (approximately 160 OTUs), which was used in the construction of a phylogenetic tree. Despite the diversity of SRB, the rarefaction curves indicated good representation of the SRB, particularly at the 80% similarity cutoff (data not shown here). In both seasons, the diversity indices (Chao1, ACE and Shannon) did not vary significantly with S. alterniflora invasion (Table 4), suggesting its minimal impact on the diversity of SRB.

Table 4.

Summary of the diversity indices of dsrB genes amplified from sediment samples in the S. alterniflora (S), transition (T), and P. australis (P) stands.

| Season | Sample | NSa | 90% Similarity cutoff | 80% Similarity cutoff | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOb | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | NOb | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | |||

| Spring | PIa | 414 | 187 | 421 | 600 | 4.7 | 144 | 306 | 356 | 4.3 |

| PIb | 704 | 310 | 1096 | 2137 | 5.4 | 202 | 456 | 846 | 4.8 | |

| TIa | 778 | 294 | 1277 | 2605 | 5.3 | 203 | 530 | 847 | 4.8 | |

| TIb | 706 | 307 | 1000 | 2179 | 5.3 | 215 | 493 | 874 | 4.8 | |

| SIa | 971 | 165 | 331 | 460 | 4.7 | 138 | 199 | 215 | 4.5 | |

| SIb | 701 | 303 | 1558 | 3092 | 5.3 | 214 | 584 | 1073 | 4.9 | |

| Summer | PIIa | 523 | 274 | 591 | 989 | 5.3 | 193 | 302 | 463 | 4.9 |

| PIIb | 675 | 285 | 979 | 2650 | 5.3 | 191 | 466 | 1093 | 4.7 | |

| TIIa | 740 | 311 | 883 | 1349 | 5.5 | 209 | 483 | 680 | 4.9 | |

| TIIb | 686 | 279 | 882 | 1923 | 5.3 | 184 | 455 | 705 | 4.7 | |

| SIIa | 704 | 285 | 1015 | 2283 | 5.2 | 185 | 407 | 570 | 4.6 | |

| SIIb | 890 | 140 | 324 | 368 | 4.6 | 116 | 163 | 164 | 4.3 | |

The diversity indices were calculated at 90 and 80% similarity cutoffs using normalized sequence numbers. Sample names are as described in Figure 1.

NSa, number of sequences; NOb, Number of OTUs.

Phylogenetic analyses of mcrA and dsrB OTUs

To determine the identity and phylogenetic positions of the collected sequences, trees were constructed for both the methanogens and SRB. OTU representatives of both genes (79 and 70% similarity OTUs for mcrA and dsrB, respectively) were translated into amino acid sequences, and their closest relatives were searched for using the NCBI amino acid non-redundant database (BLASTp). For SRB, a 70% similarity cutoff was selected because the numbers of OTUs observed at 90 and 80% similarity cutoffs were relatively large (up to 300) with small variation (<6.5%) among their relative composition.

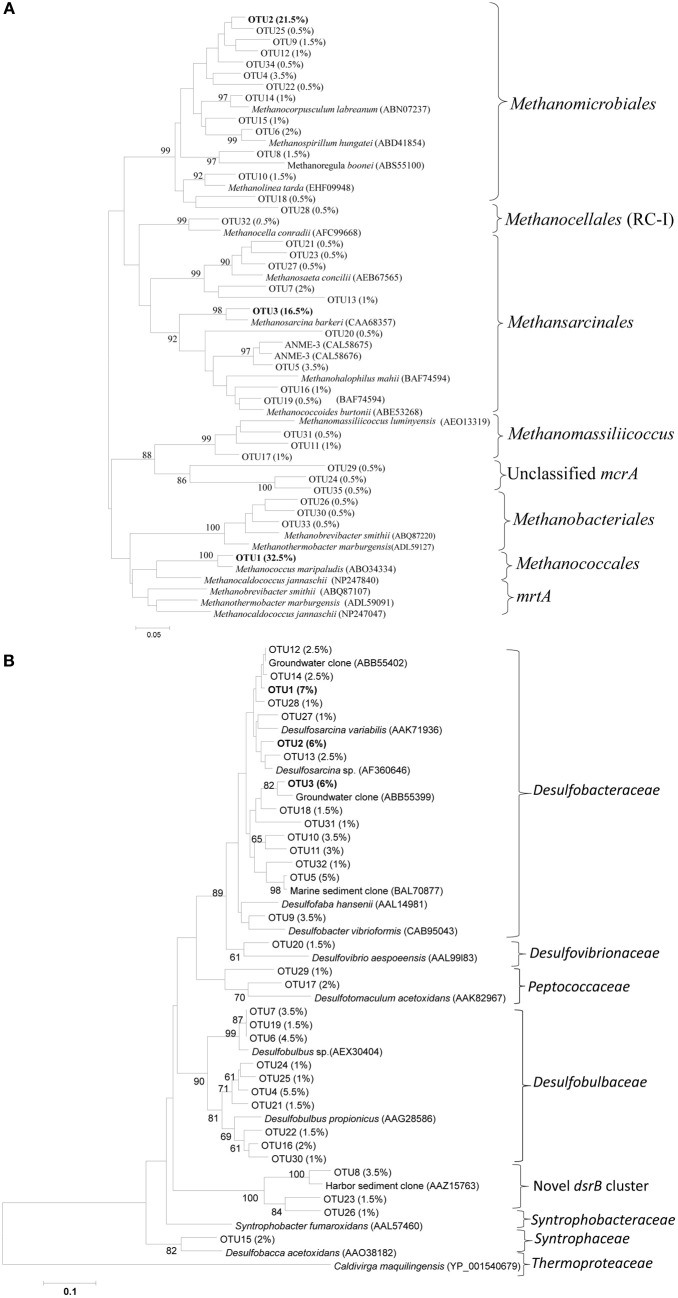

McrA OTUs were dominated by OTU1, 2 and 3, representing approximately 32.5, 21.5, and 16.5% of the total sequences (Figure 3A). OTU1 was closely related to the mcrA of Methanococcus, whereas OTU2 and 3 were related to the mcrA of Methanomicrobiales and Methanosarcina, respectively. Most of the mcrA gene sequences were closely related to the methanogen orders Methanomicrobiales, Methanosarcinales and Methanococcales, although other methanogens such as Methanobacteriales, ANME (1 and 3) and ZC-I were also detected in the salt marsh (Figure 3A). As the primers used in this study (mlas/mcrA-rev) can amplify mcrA and mrtA genes (Steinberg and Regan, 2009), the presence of large number of sequences (32.5%) related to Methanococcales (Luton et al., 2002), methanogens carrying mcrA and mrtA genes, might overestimate the abundance and diversity of the total methanogens. Interestingly, at both similarity cutoffs, Methanococcales was represented by a single OTU that is closely related (approximately 95% at the amino-acid level) to Methanococcus maripaludis. The occurrences of Methanomicrobiales, Methanosarcinales and Methanococcales in the mcrA sequences were also supported by the results from the analysis of archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences where the above three methanogenic orders were also the most abundant in the phylum Euryarchaeota, which itself represented approximately 35% of the total archaeal sequences (data not shown here).

Figure 3.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees of (A) mcrA and (B) dsrB gene OTUs recovered from the Dongtan tidal salt marsh located in the Yangtze estuary. The trees were constructed based on the inferred amino acids of the OTU-representative nucleotide sequences. Percentages in the parenthesis indicate the percent of sequences included in that specific OTU. Only OTUs containing at least 0.5 and 1% of the total sequences mcrA and dsrB OTUs, respectively, are presented here.

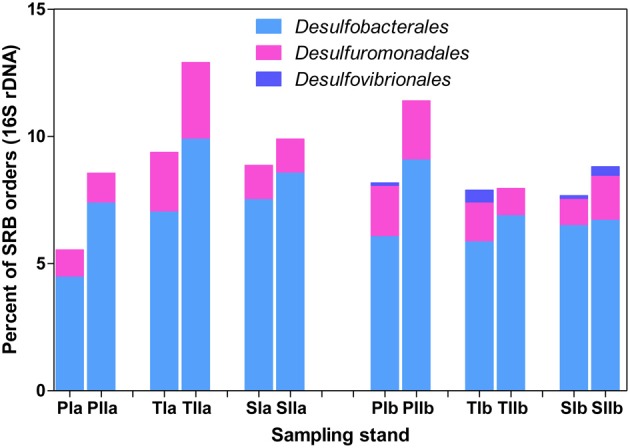

Among the SRB, the variations among the proportions of OTUs were very low. For instance, the most dominant 70% similarity OTUs (OTU 1, 2, and 3) represented approximately 7, 6 and 6% of the total sequences, respectively (Figure 3B). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that more than 85% of the sequences were related to Deltaproteobacteria, suggesting their significant role in the marsh. In the dsrB gene sequences, the most frequently detected families of SRB appeared to be Desulfobacteraceae (49.2 ± 8.5%) and Desulfobulbaceae (29.6 ± 7.8%), whereas sequences related to Desulfovibrionaceae, Peptococcaceae, Syntrophaceae and Syntrophobacteraceae were detected, but at much lower proportions (total <8%), The dominance of Desulfobacteraceae was mainly contributed to by three dominant dsrB OTUs that were either closely related to the genus Desulfosarcina or uncultured family members (Figure 3B). Interestingly, we detected relatively a large proportion of OTUs (11.3 ± 5.1%) clustered distinctly from the previously isolated dsrB phylotypes. This novel cluster formed a distinct deep branch between Desulfobulbaceae (with approximately 56.6% amino-acid sequence similarities) and Syntrophobacteraceae (with approximately 61% amino-acid sequence similarities) (Figure 3B). An analysis of the total bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences indicated consistent results with the dsrB gene sequence results in that sequences related to the order Desulfobacterales were dominant (Figure 7).

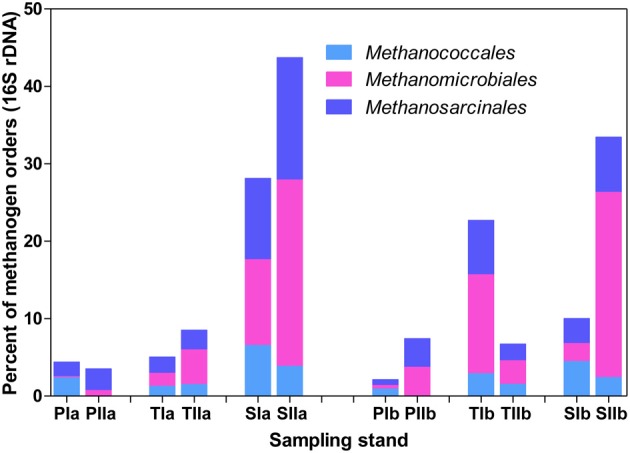

Figure 7.

Proportions of the dominant orders of SRB analyzed from 16S rRNA gene sequences of Bacteria. The samples were collected from P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands. The sample names are as described in Figure 1.

Community distribution patterns with S. alterniflora invasion

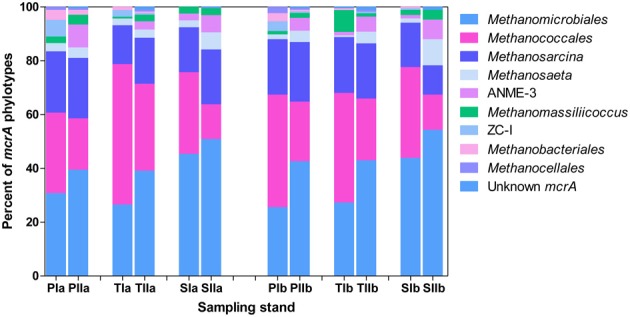

Both invasion- and growth-associated variations in the relative proportions of mcrA and dsrB phylotypes were analyzed. For methanogens, the orders Methanomicrobiales, Methanococcales and Methanosarcinales together represented 85–90% of the total mcrA sequences (Figure 4). However, their proportion responded differently to the invasion of S. alterniflora. For instance, the mean proportions of Methanomicrobiales, the most dominant methanogens detected in the salt marsh (representing approximately 33.1 and 44% of the sequences in the spring and summer, respectively), were greater in the S. alterniflora stands than in the P. australis stands by approximately 58 and 28% in the spring and summer samples, respectively (Figure 4). This might demonstrate the effect of S. alterniflora invasion in promoting the proliferation of Methanomicrobiales. Almost a reverse phenomenon was observed for the order Methanococcales (Figure 4). In the spring, Methanococcales represented approximately 38% of the total mcrA sequences, but its mean proportions indicated approximately 10% reductions from P. australis to S. alterniflora stands. In the summer, not only were the mcrA sequences related to Methanococcales reduced (approximately 20% of the total mcrA gene sequences), but higher reductions (approximately 37%) were observed from P. australis to S. alterniflora stands. Hence, S. alterniflora growth appeared to favor Methanomicrobiales over Methanococcales. However, the two main genera of the order Methanosarcinales (Methanosarcina and Methanosaeta) represented approximately 20 and 24% of the mcrA sequences, respectively, although they did not display similar trends with S. alterniflora invasion. The mean proportions of Methanosaeta increased with S. alterniflora invasion. In contrast, the mean proportions of the genus Methanosarcina did not display significant variations with either the invasion or growth of S. alterniflora (Figure 4). With the exception of ANME-3, most of the rare mcrA phylotypes, such as Methanobacteriales, Methanocellales and ZC-I, detected in this study dominated the P. australis stands. This is consistent with the diversity index results (Table 3) that indicated lower diversity of methanogens in the S. alterniflora stands compared with the transition or P. australis stands.

Figure 4.

Proportions of the major mcrA phylotypes detected in sediments from P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands. The sample names are as described in Figure 1.

Trends in the distribution patterns of the dominant methanogen orders revealed that the mcrA analysis results were generally consistent with the results of the 16S rRNA gene analysis results, except that Methanococcales represented relatively lower proportions of the 16S rRNA gene sequences (Figure 5). The higher proportions of Methanococcales in the mcrA sequences compared with the 16S rRNA gene sequences might be explained by the likely amplification of both mcrA and mrtA genes. Hence, methanogens might be slightly overestimated, particularly in the spring samples where Methanococcales represented a relatively large proportion of the sequences.

Figure 5.

Proportions of the dominant methanogen orders detected from 16S rRNA gene sequences of Archaea. The samples were collected from P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands. The sample names are as described in Figure 1.

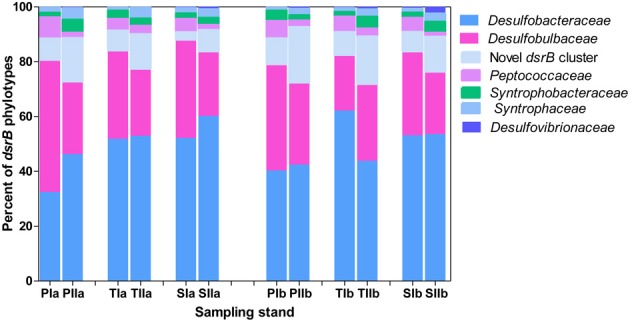

Based on the frequency of nucleotide sequences recovered from the salt marsh, dsrB phylotypes were dominated by Deltaproteobacteria, particularly the families of the order Desulfobacterales (Figure 6), which represented more than 85% of the sequences. Except for the small increase of its relative proportion at PIa and reduction observed at TIIb, Desulfobacteraceae (the most dominant family in the order Desulfobacterales) did not display significant change from the spring to the summer. On the other hand, at the S. alterniflora invaded sediments the mean proportion of Desulfobacteraceae increased from approximately 61 to 54% at locations “a” and “b”, respectively (Figure 6). In contrast, the proportion of Desulfobulbaceae, the second dominant family in the order Desulfobacterales, decreased in the summer (by approximately 45%). However, insignificant change was observed with S. alterniflora invasion. Despite the lower proportions (4.0 ± 2.0%), similar trends were observed for the family Peptococcaceae (Figure 6) within Desulfobulbaceae. Approximately 50% increases were observed from the spring to the summer in the proportions of the novel dsrB cluster (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proportions of major dsrB families detected in sediments from P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands. The sample names are as described as Figure 1.

The abundance patterns of dsrB phylotypes were generally consistent with 16S rRNA gene patterns of Deltaproteobacteria-related phylotypes (Figure 7). Desulfobacterales was represented by 4.5–10% of the total bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences, whereas Desulfuromonadales was represented by 1–5% of the sequences. Similar to dsrB, some orders of SRB, such as Desulfovibrionales, were represented by very low proportions among the 16S rRNA gene sequences (Figure 7). Generally, insignificant variations in the proportions of SRB phylotypes were observed with the invasion of S. alterniflora, although members of Desulfobacterales and Desulfovibrionales were slightly increased with the growth of S. alterniflora.

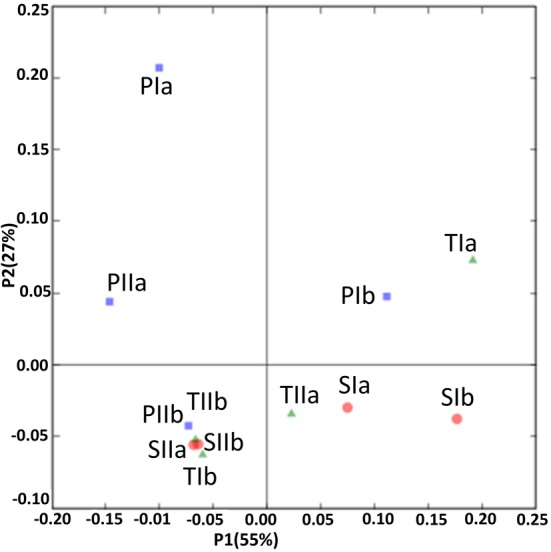

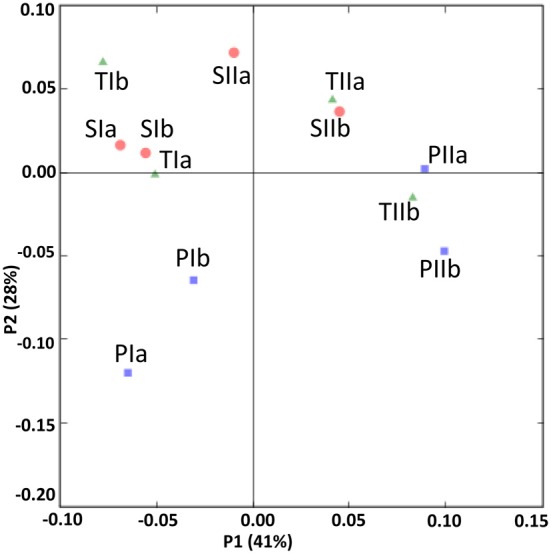

Comparison of communities in different stands

Sediment samples from the different stands were clustered using PCA and environment clustering through weighted normalized UniFrac analysis. With a few exceptions (PIa, TIb and TIIa), PC1 indicated a clear distinction between the methanogen communities of the spring and summer samples (Figure 8). Moreover, most of the communities from the S. alterniflora-influenced samples were also clustered distinctly from non-influenced samples in PC2, signifying the variation in the structures of methanogens in the S. alterniflora and P. australis stands. These variations were clearly supported by the dendrogram clustering of environments where samples from S. alterniflora influenced stands, and different growing seasons clustered separately (data not shown).

Figure 8.

UniFrac analyses showing the PCA plots of methanogen communities based on sequence abundance data in the P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands. The sample names are as described in Figure 1.

The SRB communities of the spring and summer samples were clustered distinctly along PC1 (Figure 9), which is consistent with the abundance data. The SRB community structures in the samples from the P. australis stands and S. alterniflora stands distributed separately along PC2 (Figure 9). These results were also supported by the dendrogram of the environment cluster (data not shown).

Figure 9.

UniFrac analyses showing the PCA plots of SRB based on sequence abundance data in the P. australis (P), S. alterniflora (S) and transition (T) stands. The sample names are as described in Figure 1.

Discussion

The extensive expansion of S. alterniflora is recognized as one of the major threats to the natural ecology of salt marshes, because the plant can alter the carbon and nitrogen contents of sediments (Turner, 1993; Liao et al., 2007; Page et al., 2010). This, in turn, may influence the carbon and nitrogen cycles in the sediments and the microbes that provide these functions. To understand the impact of S. alterniflora invasion on the community structure of methanogens and SRB in the salt marsh sediments of Dongtan, functional gene (mcrA and dsrB)-based investigations were conducted using samples from stands covered by monocultures of P. australis, S. alterniflora and a transition zone where both plants were available.

The higher methane flux rates detected in the S. alterniflora stands, particularly during the summer, were not surprising because many studies have already determined the potential of S. alterniflora to increase the gas flux rates of environments. This might be associated with the higher density of S. alterniflora living biomass, greater gas transportation capacity and substrate stimulation of methane-producing microorganisms (Cheng et al., 2007; Tong et al., 2012). Substrate stimulation of methanogens might be likely, as sediments from S. alterniflora stands displayed higher TC and TN levels compared with the native P. australis stands. Moreover, increases in the ratio of methane to carbon dioxide in the S. alterniflora stands might suggest the invasion of the S. alterniflora resulted in greater methane production. This, in turn, could explain the stimulation of methanogens after the invasion. The relatively high soil temperatures detected during the summer could favor the activity of sediment microbes, which might explain the slight reductions of the TC and TN levels of the sediments.

Abundances of methanogens and SRB were increased with the invasion and growth of S. alterniflora, which could be related to their available nutrients in the S. alterniflora stands. (Schubauer and Hopkinson, 1984; Peng et al., 2011). For instance, Liao and his colleagues (Liao et al., 2008) indicated that the annual litter mass in S. alterniflora stands is approximately 22.8% higher than in P. australis stands. This abundant S. alterniflora-derived organic matter is hydrolyzed and fermented by heterotrophic microorganisms, which can release excess substrates for both methanogens and SRB. The higher abundance of methanogens and SRB in the S. alterniflora stands is also consistent with a report that identified higher TC mineralization capabilities of dissolved organic matter derived from S. alterniflora compared with P. australis-derived matter (Bushaw-Newton et al., 2008). Indeed, the enrichment of sediments with S. alterniflora detritus has been shown to fuel the activity of anaerobic microbial communities (Andersen and Hargrave, 1984; Kepkay and Andersen, 1985). Hines and his colleagues (Hines et al., 1999) detected a high number of active sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) during the active growth stage of S. alterniflora in salt marsh sediments, which may be associated with substrate stimulation of sulfate reducers from root exudates. In contrast, a study on Jiuduansha Island, in the Yangtze River estuary, indicated that the senescence stage of S. alterniflora favors the richness and abundance of SRB (Nie et al., 2009), which is likely associated with litter decomposition-related substrate stimulation of SRB. Despite contrasting reports, it is possible to argue that the presence of S. alterniflora in environments can alter the natural abundance and activity of SRB. In addition to the relative contribution of S. alterniflora to the total carbon and nitrogen levels of sediments (Moran and Hodson, 1990; Liao et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2011), S. alterniflora tissues are important sources of trimethylamine (Cavalieri, 1983). Trimethylamine can be a noncompetitive substrate for methanogens. Moreover, acetate might be released from the root exudates or tissue decompositions could be used by SRB and methanogens (King, 1984; Watkins et al., 2012). Temperature is also one of the important factors controlling the growth of methanogens (Zeikus and Winfrey, 1976; Turetsky et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010), so it is reasonable to conclude that higher abundances of methanogens and higher methane flux rates were detected during the summer and positively correlated with the soil temperature.

Although the abundances of methanogens were higher in the S. alterniflora stands of both seasons, their diversities were lower in the S. alterniflora stands compared with the P. australis stands. Hence, S. alterniflora invasion-related abundance increases might not have contributions from all members of the methanogens, and S. alterniflora might select methanogen communities. Although the proportions of Methanomicrobiales were increased with S. alterniflora invasion, Methanococcales and many of other rare mcrA phylotypes (e.g., Methanobacteriales, Methanocellales and ZC-I) were reduced, which might explain the lower diversity of methanogens in the S. alterniflora stands. Methanomicrobiales and Methanococcales (hydrogenotrophic methanogens) unexpectedly dominated the salt marsh (>60%), although they can be easily outcompeted by SRB (Oremland et al., 1982). However, the availability of excess substrates in such productive environments (Schubauer and Hopkinson, 1984; Peng et al., 2011) might reduce the competition and support the growth of both microbial groups. Interestingly, Methanococcales was represented by the most dominant OTU (OTU1, approximately 32.5%). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that it is closely related (96%) to Methanococcus maripaludis, a methanogen that is commonly distributed in marine and salt marsh sediments (Jones et al., 1983). The reasons for such dominance by a single methanogen species are not clear, but the extremely fast-growing nature of this mesophilic methanogen (Jones et al., 1983) could be triggered by the availability of excess substrates in sediments. On the other hand, the proportion of Methanosarcina did not display significant variation with the invasion and growth of S. alterniflora, which could be associated with their metabolic flexibility to utilize different substrates (King, 1984; Lyimo et al., 2000). However, the proportion of the genus Methanosaeta, strict acetate utilizers, was much lower in the spring but significantly increased with the growth of plants in the summer, indicating the availability of acetate increased with the growth of plants, particularly in the S. alterniflora stands where the microbes displayed marked increases.

The current study also revealed that more than 80% of the dsrB phylotypes that were detected were members of the order Desulfobacterales. These microbes are nutritionally versatile and can oxidize acetate and other organic compounds (Muyzer and Stams, 2008). The SRBA spectrum of substrates from the root exudates and decomposition of S. alterniflora and P. australis tissues could be available for these diverse SRB (Nie et al., 2009). Except for the small changes in Desulfobacteraceae, the proportions of dsrB families in both sampling seasons generally displayed minor variations with S. alterniflora invasion. The reason for such insignificant variation was not clear; however, nutrients that could be released from S. alterniflora tissue decomposition or root exudates might support most SRB phylotypes. The large numbers of novel dsrB OTUs that were clustered distinctly between the families Syntrophobacteraceae and Desulfobulbaceae might offer a clue into the presence of novel SRB types in the tidal salt marsh. Although the physiology of these novel sulfate-reducing phylotypes cannot be speculated about at this time, they could grow with both plant types, particularly in the stands of P. australis.

In conclusion, the invasion of S. alterniflora in the salt marsh sediments of Dongtan might support the proliferation of methanogens and SRB. However, significant impacts were only observed on the diversity of methanogens.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professor Andrew Ogram of University of Florida for reading the draft manuscript and providing us with important comments. This project was partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31070097 and 30930019), National Key Technology R & D Program of China (2010BAK69B14) and Major Program of Science and Technology Department of Shanghai (10DZ1200700).

References

- Abram J. W., Nedwell D. B. (1978). Hydrogen as a substrate for methanogenesis and sulphate reduction in anaerobic saltmarsh sediment. Arch. Microbiol. 117, 93–97 10.1007/BF00689357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen F. O., Hargrave B. T. (1984). Effects of Spartina detritus enrichment on aerobic/ anaerobic benthic metabolism in an intertidal sediment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 16, 161–171 10.3354/meps016161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. L., Fauque G. D. (2009). Biochemistry, physiology and biotechnology of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 68, 41–98 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)01202-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batten K. M., Scow K. M., Davies K. F., Harrison S. P. (2006). Two invasive plants alter soil microbial community composition in serpentine grasslands. Biol. Invasions 8, 217–230 10.1007/s10530-004-3856-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D., Ben Mahfoudh K., Wagner M., Loy A. (2011). Barcoded primers used in multiplex amplicon pyrosequencing bias amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 7846–7849 10.1128/AEM.05220-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushaw-Newton K. L., Kreeger D. A., Doaty S., Velinsky D. J. (2008). Utilization of Spartina- and Phragmites-derived dissolved organic matter by bacteria and Ribbed Mussels (Geukensia demissa) from Delaware bay salt marshes. Estuar. Coast. 31, 694–703 10.1007/s12237-008-9061-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri A. J. (1983). Proline and glycinebetaine accumulation by Spartina alterniflora Loisel. in response to NaCI and nitrogen in a controlled environment. Oecologia 57, 20–24 10.1007/BF00379556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Zhao B., Ren W., Saunders S. C., Ma Z., Li B., et al. (2008). Invasive Spartina and reduced sediments: shanghai's dangerous silver bullet. J. Plant Ecol. 1, 79–84 10.1093/jpe/rtn007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Peng R., Chen J., Luo Y., Zhang Q., An S., et al. (2007). CH4 and N2O emissions from Spartina alterniflora and Phragmites australis in experimental mesocosms. Chemosphere 68, 420–427 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C. H. (1993). Thirty years of ecological engineering with Spartina plantations in China. Ecol. Eng. 2, 261–289 10.1016/0925-8574(93)90019-C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dar S. A., Yao L., Van Dongen U., Kuenen J. G., Muyzer G. (2006). Analysis of diversity and activity of sulfate-reducing bacterial communities in sulfidogenic bioreactors using 16S rRNA and dsrB genes as molecular markers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 594–604 10.1128/AEM.01875-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantner S., Andersson A. F., Alonso-Saez L., Bertilsson S. (2011). Novel primers for 16S rRNA-based archaeal community analyses in environmental samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 84, 12–18 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geets J., Borremans B., Diels L., Springael D., Vangronsveld J., Van Der Lelie D., et al. (2006). DsrB gene-based DGGE for community and diversity surveys of sulfate-reducing bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 66, 194–205 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni S. J. (1991). The polymerase chain reaction, in Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics, eds Stackebrandt E., Goodfellow M. (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 177–203 [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni S. J., Delong E. F., Olsen G. J., Pace N. R. (1988). Phylogenetic group-specific oligodeoxynucleotide probes for identification of single microbial Cells. J. Bacteriol. 170, 720–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C. V., Wren I. F., Herman D. J., Firestone M. K. (2005). Plant invasion alters nitrogen cycling by modifying the soil nitrifying community. Ecol. Lett. 8, 976–985 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00802.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines M. E., Evans R. S., Sharak Genthner B. R., Willis S. G., Friedman S., Rooney-Varga J. N., et al. (1999). Molecular phylogenetic and biogeochemical studies of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the rhizosphere of spartina alterniflora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 2209–2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota M., Tang Y., Hu Q., Hirata S., Kato T., Mo W., et al. (2004). Methane emissions from different vegetation zones in a Qinghai-Tibetan plateau wetland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36, 737–748 10.1016/j.soilbio.2003.12.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmer M., Kristensen E. (1994). Coexistence of sulfate reduction and methane production in an organic-rich sediment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 107, 77–184 10.3354/meps107177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L. F., Luo Y. Q., Chen J. K., Li B. (2009). Ecophysiological characteristics of invasive Spartina alterniflora and native species in salt marshes of Yangtze River estuary, China. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 81, 74–82 10.1016/j.ecss.2008.09.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W. J., Paynter M. J. B., Gupta R. (1983). Characterization of Methanococcus maripaludis sp. nov., a new methanogen isolated from salt marsh sediment. Arch. Microbiol. 135, 91–97 10.1007/BF00408015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaku N., Ueki A., Ueki K., Watanabe K. (2005). Methanogenesis as an important terminal electron accepting process in estaurine sediment at the mouth of Orikasa river. Microbes. Environ. 20, 41–52 10.1264/jsme2.20.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kepkay P. E., Andersen F. O. (1985). Aerobic and anaerobic metabolism of a sediment enriched with Spartina detritus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 21, 53–161 10.3354/meps021153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King G. M. (1984). Utilization of hydrogen, acetate, and “noncompetitive”; substrates by methanogenic bacteria in marine sediments. J. Geomicrobiol. 3, 275–306 10.1080/01490458409377807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knittel K., Losekann T., Boetius A., Kort R., Amann R. (2005). Diversity and distribution of methanotrophic archaea at cold seeps. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 467–479 10.1128/AEM.71.1.467-479.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C., Luo Y., Jiang L., Zhou X., Wu X., Fang C., et al. (2007). Invasion of Spartina alterniflora enhanced ecosystem carbon and nitrogen stocks in the Yangtze estuary, China. Ecosystems 10, 1351–1361 10.1007/s10021-007-9103-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C. Z., Luo Y. Q., Fang C. M., Chen J. K., Li B. (2008). Litter pool sizes, decomposition, and nitrogen dynamics in Spartina alterniflora-invaded and native coastal marshlands of the Yangtze Estuary. Oecologia 156, 589–600 10.1007/s00442-008-1007-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Ding W., Jia Z., Cai Z. (2010). Influence of niche differentiation on the abundance of methanogenic archaea and methane production potential in natural wetland ecosystems across China. Biogeosci. Discuss 7, 7629–7655 10.5194/bgd-7-7629-2010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Whitman W. B. (2008). Metabolic, phylogenetic, and ecological diversity of the methanogenic archaea. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1125, 171–189 10.1196/annals.1419.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luton P. E., Wayne J. M., Sharp R. J., Riley P. W. (2002). The mcrA gene as an alternative to 16S rRNA in the phylogenetic analysis of methanogen populations in landfill. Microbiology 148, 3521–3530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyimo T. J., Pol A., Camp H. J. M. O. D., Harhangi H. R., Vogels G. D. (2000). Methanosarcina semesiae sp. nov., a dimethylsulfide-utilizing methanogen from mangrove sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50, 171–178 10.1099/00207713-50-1-171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M. A., Hodson R. E. (1990). Contributions of degrading Spartina alterniflora lignocellulose to the dissolved organic carbon pool of a salt marsh. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 62, 161–168 10.3354/meps062161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer G., Stams A. J. M. (2008). The ecology and biotechnology of sulphate-reducing bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 441–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie M., Wang M., Li B. (2009). Effects of salt marsh invasion by Spartina alterniflora on sulfate-reducing bacteria in the Yangtze River estuary, China. Ecol. Eng. 35, 1804–1808 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2009.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oremland R. S., Marsh L. M., Polcin S. (1982). Methane production and simultanouse sulafte reduction in anoxic, salt marsh sediments. Nature 296, 143–145 10.1038/296143a016346294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page H. M., Lastra M., Rodil I. F., Briones M. J. I., Garrido J. (2010). Effects of non-native Spartina patens on plant and sediment organic matter carbon incorporation into the local invertebrate community. Biol. Invasions 12, 3825–3838 10.1007/s10530-010-9775-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R. H., Fang C. M., Li B., Chen J. K. (2011). Spartina alterniflora invasion increases soil inorganic nitrogen pools through interactions with tidal subsidies in the Yangtze Estuary, China. Oecologia 165, 797–807 10.1007/s00442-010-1887-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy K. J., Nedwell D. B., Embley T. M. (2003). Analysis of the sulfate-reducing bacterial and methanogenic archaeal populations in contrasting antarctic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 3181–3191 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3181-3191.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravit B., Ehrenfeld J. G., Haggblom M. M. (2003). A comparison of sediment microbial communities associated with Phragmites australis and Spartina alterniflora in two brackish wetlands of New Jersey. Estuaries 26, 465–474 10.1007/BF02823723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss P. D., Westcott S. L., Ryabin T., Hall J. R., Hartmann M., Hollister E. B., et al. (2009). Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541 10.1128/AEM.01541-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubauer J. P., Hopkinson C. S. (1984). Above- and belowground emergent macrophyte production and turnover in a coastal marsh ecosystem, Georgia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 29, 1052–1065 10.4319/lo.1984.29.5.1052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senior E., Borje E. L., Ibrahim M. B., Nedwell D. B. (1982). Sulfate reduction and methanogenesis in the sediment of a saltmarsh on the east coast of the United Kingdom. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43, 987–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. M., Regan J. M. (2008). Phylogenetic comparison of the methanogenic communities from an acidic, oligotrophic fen and an anaerobic digester treating municipal wastewater sludge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 6663–6671 10.1128/AEM.00553-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. M., Regan J. M. (2009). mcrA-targeted real-time quantitative PCR method to examine methanogen communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 4435–4442 10.1128/AEM.02858-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong C., Wang W. Q., Huang J. F., Gauci V., Zhang L. H., Zeng C. S. (2012). Invasive alien plants increase CH4 emissions from a subtropical tidal estuarine wetland. Biogeochemistry 111, 677–693 10.1007/s10533-012-9712-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turetsky M. R., Treat C. C., Waldrop M. P., Waddington J. M., Harden J. W., McGuire A. D. (2008). Short-term response of methane fluxes and methanogen activity to water table and soil warming manipulations in an Alaskan peatland. J. Geophy. Res. 113:G00A10 10.1029/2007JG0004960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. E. (1993). Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus leaching rates from Spartina alterniflora salt marshes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 92, 135–140 10.3354/meps092135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Chen Z., Xu S. (2009). Methane emission from Yangtze estuarine wetland, China. J. Geophys. Res. 114:G02011 [Google Scholar]

- Watkins A. J., Roussel E. G., Webster G., Parkes R. J., Sass H. (2012). Choline and N,N-Dimethylethanolamine as direct substrates for methanogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 8298–8303 10.1128/AEM.01941-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. L., Grosholz E. D. (2008). The invasive species challenge in estuarine and coastal environments: marrying management and science. Estuar. Coast. 31, 3–20 10.1007/s12237-007-9031-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winfrey M. R., Ward D. M. (1983). Substrates for sulfate reduction and methane production in intertidal sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45, 193–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeikus G., Winfrey M. R. (1976). Temperature limitation of methanogenesis in aquatic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 31, 99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeleke J., Lu S. L., Wang J. G., Huang J. X., Li B., Ogram A. V., et al. (2013). Methyl coenzyme M reductase A (mcrA) gene-based investigation of methanogens in the mudflat sediments of Yangtze River Estuary, China. Microb. Ecol. 66, 257–267 10.1007/s00248-012-0155-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Tian J., Jiang N., Guo X., Wang Y., Dong X. (2008). Methanogen community in Zoige wetland of Tibetan plateau and phenotypic characterization of a dominant uncultured methanogen cluster ZC-I. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1850–1860 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01606.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ding W., Cai Z., Valerie P., Han F. (2010). Response of methane emission to invasion of Spartina alterniflora and exogenous N deposition in the coastal salt marsh. Atmos. Environ. 44, 4588–4594 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.08.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]