Isolated medial posterior meniscal root tear is associated with medial tibiofemoral cartilage loss.

Abstract

Purpose:

To assess the association of meniscal root tear with the development or worsening of tibiofemoral cartilage damage.

Materials and Methods:

Institutional review board approval and written informed consent from all subjects were obtained. A total of 596 knees with radiographically depicted osteoarthritis were randomly selected from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis study cohort. Cartilage damage was semiquantitatively assessed by using the Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) system (grades 0–6). Subjects were separated into three groups: root tear only, meniscal tear without root tear, and neither meniscal nor root tear. A log-binomial regression model was used to calculate the relative risks for knees to develop incident or progressing cartilage damage in the root tear group and the meniscal tear group, with the no tear group serving as a reference.

Results:

In the medial tibiofemoral joint, there were 37 knees with isolated medial posterior root tear, 294 with meniscal tear without root tear, and 264 without meniscal or root tear. There were only two lateral posterior root tears, and no anterior root tears were found. Thus, the focus was on the medial posterior root tear. The frequency of severe cartilage damage (WORMS ≥5) was higher in the group with root tear than in the group without root or meniscal tear (76.7% vs 19.7%, P < .0001) but not in the group with meniscal but no root tear (76.7% vs 65.2%, P = .055). Longitudinal analyses included 33 knees with isolated medial posterior root tear, 270 with meniscal tear, and 245 with no tear. Adjusted relative risk of cartilage loss was 2.03 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.18, 3.48) for the root tear group and 1.84 (95% CI: 1.32, 2.58) for the meniscal tear group.

Conclusion:

Isolated medial posterior meniscal root tear is associated with incident and progressive medial tibiofemoral cartilage loss.

© RSNA, 2013

Introduction

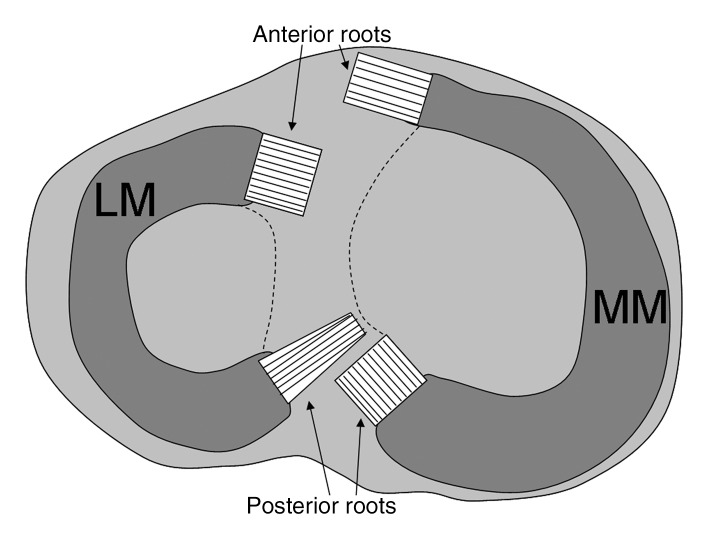

The meniscal roots are ligamentous attachments that anchor the anterior and posterior horns of the meniscus to the tibial plateau (Fig 1) (1). Tears of the meniscal roots are distinctly different from tears of the anterior or posterior horn of the meniscus (2). Root tears may or may not be associated with tears of the meniscus, and isolated root tears can occur with no tearing of the meniscus itself (3). When the meniscal root tears, the meniscus is no longer held within the joint, possibly resulting in meniscal extrusion (4,5).

Figure 1:

Schematic of meniscal roots. The anterior root of the medial meniscus (MM) inserts broadly into the anterior intercondylar crest. The anterior root of the lateral meniscus (LM) inserts into a portion of the anterior intercondylar crest in front of the lateral tibial tubercle and lateral to the anterior cruciate ligament, with which it partially blends. The posterior root of the medial meniscus inserts into the posterior slope of the medial tibial tubercle. Most of the posterior root of the lateral meniscus inserts into a horizontal part of the posterior intercondylar area, but some fibers attach to the posterior slope of the lateral tubercle.

The meniscal roots are readily identifiable on magnetic resonance (MR) images (6). Previous studies based on MR imaging and arthroscopic findings showed cross-sectional associations between medial meniscal root tears and medial tibiofemoral cartilage loss (2,5,7–9). However, these studies were based on a relatively small sample of subjects and were not longitudinal.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the association of medial meniscal root tears with the development or worsening of medial tibiofemoral cartilage loss by using a longitudinal study design.

Materials and Methods

One author (A.G.) has received consultancies, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Genzyme, Stryker, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Astra Zeneca and is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab (Boston, Mass), a company providing image assessment services. One author (F.W.R.) is chief medical officer and shareholder of Boston Imaging Core Lab and has received consultancies, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Merck Serono and the National Institutes of Health. One author (M.D.C.) is a shareholder of Boston Imaging Core Lab.

Subjects

Subjects were participants in the Multicenter Osteoarthritis (MOST) study, a prospective epidemiologic study with the goal of identifying risk factors for incident and progressive knee osteoarthritis (OA). The study included 3026 people aged 50–79 years who have or are at high risk of developing OA. They were recruited from two U.S. communities, Birmingham, Ala, and Iowa City, Iowa, through mass mailing of letters and study brochures, supplemented by media and community outreach campaigns. MOST study subjects were recruited and enrolled between June 2003 and March 2005 (10). The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Iowa, University of Alabama at Birmingham, University of California at San Francisco, and Boston University School of Medicine. We obtained written informed consent from all patients.

Subjects considered at high risk for developing knee OA included those who were overweight or obese; had knee pain, aching, or stiffness on most of the past 30 days; had a history of knee injury that made it difficult to walk for at least 1 week; or had previous knee surgery (11–15). Subjects were not eligible to participate in the MOST study if they had rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, renal insufficiency that required hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, or a history of cancer (except for nonmelanoma types of skin cancer); underwent or planned to undergo bilateral knee replacement surgery; were unable to walk without assistance; or were planning to move out of the area in the next 3 years.

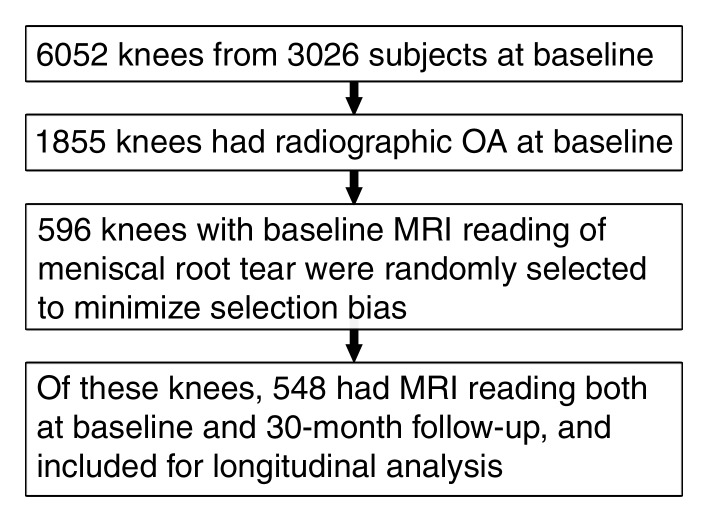

In the present study, we included subjects who had baseline radiographs of knee OA (Fig 2). To minimize selection bias, we randomly selected 596 knees (one knee per subject) from the 1855 knees with baseline radiographically depicted OA and used them for the cross-sectional analysis. Of these knees, 548 were examined with MR imaging at baseline and at 30 months and were used for the longitudinal analysis.

Figure 2:

Flowchart of the selection criteria for the study.

Radiography

All subjects underwent weight-bearing posteroanterior fixed-flexion knee radiography by using the protocol described by Peterfy et al (16) and a SynaFlexer positioning frame (Synarc, San Francisco, Calif). A musculoskeletal radiologist and a rheumatologist (D.T.F.), who both had more than 10 years of experience in reading study radiographs, independently graded the images according to the Kellgren-Lawrence grade (17). Radiographs were presented sequentially, with readers blinded to all clinical data and to MR imaging findings. Radiographs were read during approximately 8 months. Tibiofemoral OA was considered present at radiography if the Kellgren-Lawrence grade was 2 or higher. If readers disagreed on the presence of OA, readings were adjudicated by a panel of three readers (the two readers and an experienced rheumatologist who is not an author, also with 10 years of experience reading study radiographs).

Long-limb radiographs were acquired, allowing measurement of the limb’s mechanical axis, which was defined as the angle formed by the intersection of a line from the center of the head of the femur to the center of tibial spines and a line from the center of the talus to the center of tibial spines (18). Varus alignment was defined as a hip-knee-ankle angle less than 179°, neutral alignment as 179°–181° , and valgus alignment as greater than 181°. Alignment was assessed by the aforementioned two readers (a nonauthor and D.T.F.).

MR Image Acquisition

MR imaging studies were obtained in both knees at baseline and at 30-month interval by using a 1.0-T dedicated extremity unit (OrthOne; GE Healthcare [formerly ONI Medical Systems], Wilmington, Mass) with a circumferential extremity coil. Choice of pulse sequences for the parent MOST study was based on a time-efficient sequence protocol developed by Roemer et al (19). Table 1 shows a summary of the MR sequences used in this study. Examinations were performed at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and at the University of Iowa at Iowa City by using the same MR unit.

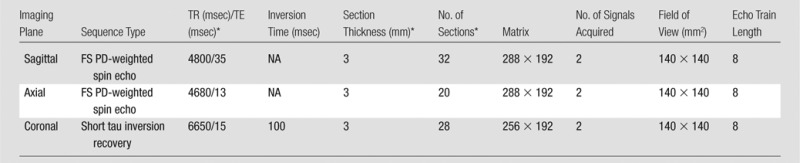

Table 1.

MR Imaging Parameters

Note.—FS PD = Fat-suppressed proton density, TE = echo time, TR = repetition time.

No intersection gap.

MR Image Interpretation

Two musculoskeletal radiologists (A.G. and F.W.R., with 11 and 9 years of experience, respectively, in standardized semiquantitative MR assessment of knee OA), who were blinded to OA grade at radiography and clinical data, systematically evaluated cartilage morphology, meniscal morphology, and effusion using the Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) system (20).

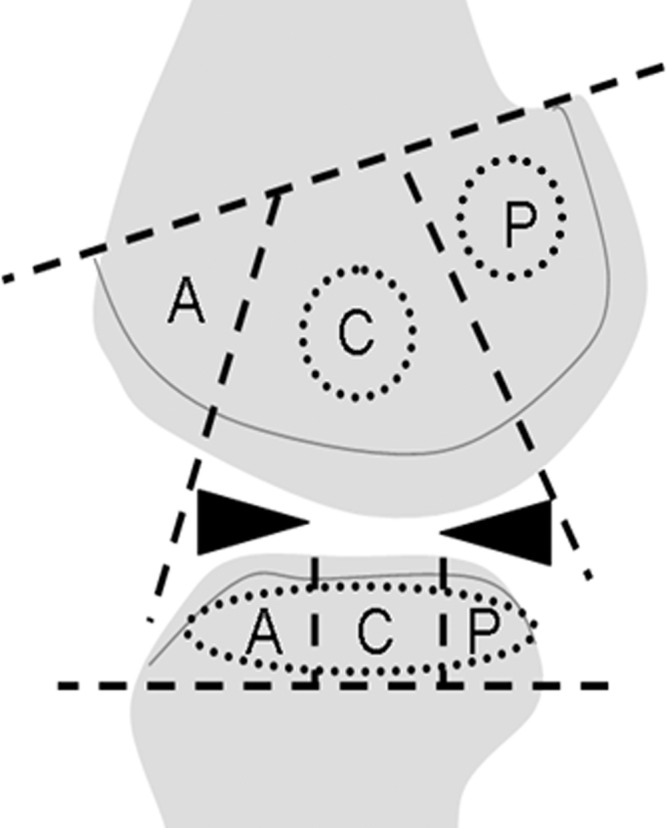

Articular cartilage of the medial tibiofemoral joint was divided into five subregions (Fig 3). With the WORMS system, cartilage morphology was graded as follows: grade 0, normal thickness and signal; grade 1, normal thickness but increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images; grade 2.0, partial-thickness focal defect less than 1 cm at its greatest width; grade 2.5, full-thickness focal defect less than 1 cm at its greatest width; grade 3, multiple areas of partial-thickness defects intermixed with areas of normal thickness or a grade 2.0 defect wider than 1 cm but less than 75% of the subregion; grade 4, diffuse (≥ 75% of the subregion) partial-thickness loss; grade 5, multiple areas of full-thickness loss or a grade 5 lesion wider than 1 cm but less than 75% of the subregion; and grade 6, diffuse (≥ 75% of the subregion) full-thickness loss. Any knees with cartilage grades of 2 or higher in at least one subregion within the medial tibiofemoral joint were considered to have cartilage damage.

Figure 3:

This schematic (sagittal section of the knee) helps explain the subregions of the medial tibiofemoral joint defined by the WORMS system. In this study, the central (C) and the posterior (P) femoral subregions, as well as all tibial subregions (anterior [A], central, and posterior), were included, but the anterior femoral subregion, which corresponds to the patellofemoral joint, was not included.

Longitudinally, worsening of cartilage damage—including incident lesions with baseline scores of 0 or 1, and progressing lesions with baseline scores of 2 or higher—was defined as a within-grade or more increase from baseline to follow-up in at least one subregion.

During a separate reading session, morphology of the meniscus was also assessed by the two readers using a 0–4-point scale as follows: grade 0, normal; grade 1, minor radial tear; grade 2, nondisplaced tear or prior surgical resection; grade 3, displaced tear or partial maceration; or grade 4, complete maceration (20). Any knees with meniscus scores of 1 or higher in at least one subregion were considered to have meniscal damage.

Effusion was also graded, again during a different reading session, by the aforementioned two radiologists (A.G. and F.W.R.) using a 0–3 scale in terms of the estimated maximal distension of the synovial cavity as follows: grade 0, normal; grade 1, less than 33% of maximum potential distension; grade 2, 33%–66% of maximum potential distension; or grade 3, greater than 66% of maximum potential distension (20).

Another musculoskeletal radiologist (M.J., who was not involved in reading the other features, with 6 years of experience in reading knee MR images) recorded the absence (score 0) or presence (score 1) of the tears of the lateral and medial anterior and/or posterior roots on the coronal short tau inversion–recovery sequence (Figs 4, 5).

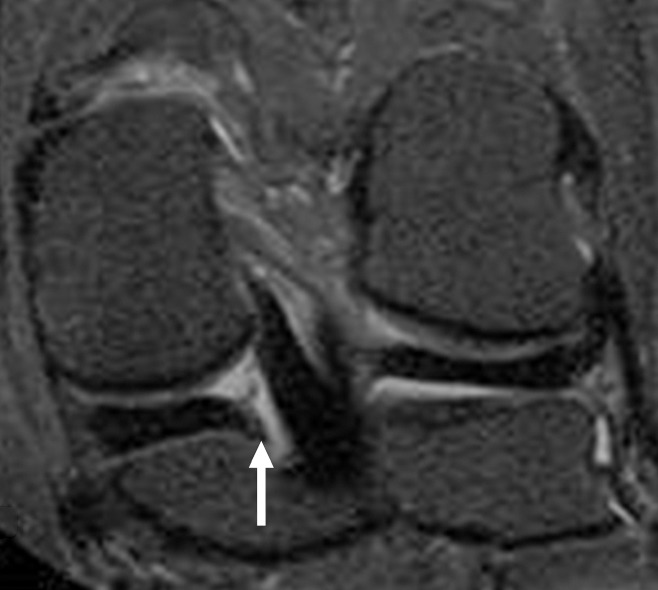

Figure 4:

Coronal short tau inversion recovery image in 57-year-old woman with intact medial posterior meniscal root (arrow) shows a linear band of hypointensity corresponding to the posterior meniscal root, which is attached to the tibial plateau. There is no apparent tibiofemoral cartilage damage.

Figure 5a:

Images in 59-year-old woman. (a) Coronal short tau inversion recovery image shows torn medial posterior meniscal root (*), signified by discontinuity of the bandlike hypointensity between the posterior horn of the medial meniscus and the tibial plateau. Note tibiofemoral cartilage damage (short arrows) and a small subchondral bone marrow edemalike lesion (long arrow). In the lateral compartment, there is no apparent cartilage damage and the root of the lateral meniscus is normal. (b) Axial fat-suppressed proton-density–weighted image confirms medial PMRT (*); lateral meniscus appears normal (arrowheads).

Figure 5b:

Images in 59-year-old woman. (a) Coronal short tau inversion recovery image shows torn medial posterior meniscal root (*), signified by discontinuity of the bandlike hypointensity between the posterior horn of the medial meniscus and the tibial plateau. Note tibiofemoral cartilage damage (short arrows) and a small subchondral bone marrow edemalike lesion (long arrow). In the lateral compartment, there is no apparent cartilage damage and the root of the lateral meniscus is normal. (b) Axial fat-suppressed proton-density–weighted image confirms medial PMRT (*); lateral meniscus appears normal (arrowheads).

Statistical Analysis

Our analyses comprise two statistical models. In the first model, we classified knees into three groups; root tear group (knees with an isolated posterior meniscal root tear [PMRT], without any meniscal abnormality other than the PMRT), meniscal tear group (knees without PMRT but with meniscal WORMS > 0, pointing to some meniscal disease), and no tear group (knees with no PMRT or other meniscal disease). In the second model, the meniscal tear group was further subdivided into mild/moderate meniscal tear (WORMS 1 or 2) and severe meniscal tear groups (WORMS 3 or 4). Thus, in this model, we classified knees into four groups; root tear group, mild/moderate meniscal tear group, severe meniscal tear group, and no tear group. First, we calculated the frequency of cartilage damage according to WORMS in each group of knees at baseline. Then, we used these two models to assess the longitudinal relation between the status of meniscus and/or meniscal root and an increase in WORMS cartilage grade, that is, development of new cartilage damage or progression of pre-existing cartilage damage at follow-up. The no tear group served as the reference in both models. The outcome (an increase in WORMS cartilage grade) was dichotomous, and we used log-binomial regression model to estimate the relative risk, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), malalignment, and clinic site. We then performed subanalyses to take into account potential confounders and made further adjustments for cartilage damage at baseline, Kellgren-Lawrence grade at baseline, and effusion scores at baseline. To calculate the intra- and interreader reproducibility, randomly selected 50 cases were reread by the same two readers (A.G., F.W.R.), with an interval of 1 month between readings.

Results

Only vertical (radial) meniscal root tears were found at baseline in this study. There were no new PMRTs at 30-month follow-up. Also, none of the subjects had any anterior root tear in the lateral or medial compartments. Furthermore, there were only two isolated lateral posterior root tears in our sample. We thus performed statistical analysis for the PMRT, meniscus, and cartilage in the medial tibiofemoral compartment only.

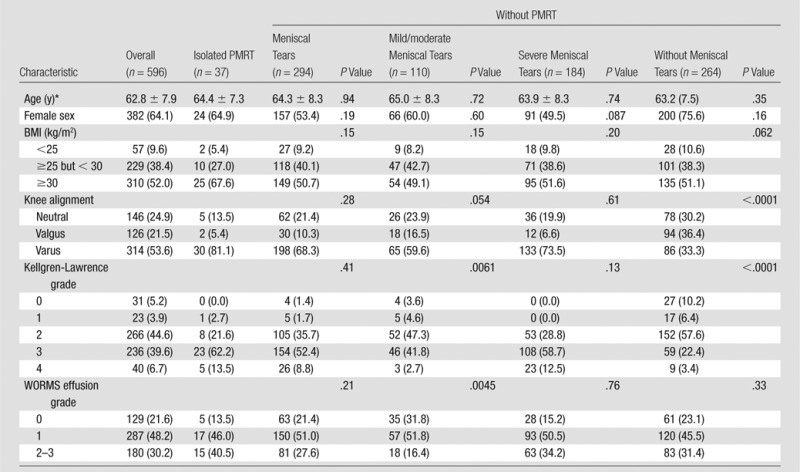

At baseline, the root tear group included 37 knees, the meniscal tear group included 294 knees (110 in mild/moderate group and 184 in severe group), and the no tear group included 264 knees (total of 596 knees). The mean age of all subjects was 62.8 years ± 7.9 (standard deviation) (mean age of women, 64.7 years ± 7.5 years; mean age of men, 62.4 years ± 8.3 years; age range for both sexes, 50–79 years), and the BMI was 30.9 kg/m2 ± 5.2 (Table 2). The majority (382 of 596 [64.1%]) were women. One hundred forty-six (24.9%) knees had neutral alignment, while 126 (21.5%) had valgus malalignment and 314 (53.6%) had varus malalignment. In terms of age, sex, and BMI distribution, statistically significant differences among groups were not observed (P = .062–.94). The root tear group and the meniscal tear group had a higher proportion of knees with varus malalignment than did the no tear group (P < .0001). Distribution of Kellgren-Lawrence grade among knees in the root tear group and the severe meniscal tear group was similar (all but one knee were Kellgren-Lawrence grade ≥ 2). The distribution of effusion severity was similar between the root tear group and the meniscal tear group (P = .21) and the no tear group (P = .33). However, a subanalysis yielded a statistically significant difference between the root tear group and the mild/moderate meniscal tear group, which had a lower prevalence of moderate to severe effusion (P = .0045).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample at Baseline

Note.—Unless otherwise indicated, data are the number of patients and data in parentheses are percentages.

Data are means ± standard deviation.

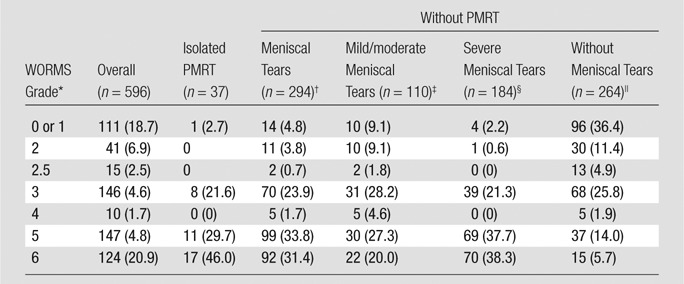

Four hundred eighty- three subjects (81.3%) exhibited variable degree of cartilage damage (Table 3). Distribution of WORMS cartilage grades in the root tear group was significantly different than the distribution in the no tear group but not that in the meniscal tear group (Table 3). The second statistihcal model revealed that presence of diffuse full-thickness cartilage loss (WORMS ≥ 5) was high (∼76%) in both the root tear group and the severe meniscal tear group, but was lower in the mild/moderate meniscal tear group (47.3%) and the no tear group (19.7%).

Table 3.

Frequency and Severity of Medial Compartment Cartilage Lesions at Baseline

Note.—Data are the number of patients and data in parentheses are percentages.

Maximum WORMS cartilage lesions in tibia or femur of the five subregions.

P = .55.

P = .022.

P = .87.

P < .0001.

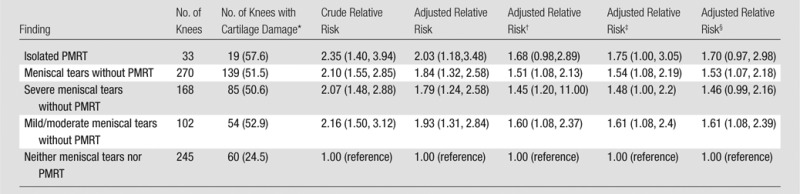

For the longitudinal analysis, the root tear group included 33 knees, while the meniscal tear group included 270 knees (168 in mild/moderate group and 102 in severe group) and the no tear group included 245 knees. The adjusted relative risk of cartilage loss (either incident loss or progression of loss) for the root tear group was 2.03 and that for the meniscal tear group was 1.84 (Table 4). Results of subanalyses are summarized in Table 4. Further adjustments for potential confounders led to loss of statistical significance by a very small margin in some cases, but overall relative risks of cartilage loss over time was higher in the root tear group and the meniscal tear group than the no tear group.

Table 4.

Relative Risk of Incident or Progressing Tibiofemoral Cartilage Damage and Meniscal Damage in the Medial Compartment of the Knee

Note.—Relative risk was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, clinic site, and malalignment. Unless otherwise indicated, data in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

Data in parentheses are percentages.

Further adjustment for prevalent cartilage damage at baseline.

Further adjustment for Kellgren-Lawrence grade at baseline.

Further adjustment for effusion scores at baseline.

Kappa statistics showed intrareader reliability for the MR assessment of PMRT was 1.00. Interreader reliability was 0.80 for meniscal morphology, 0.82 for cartilage damage, and 0.65 for effusion.

Discussion

A tear of the meniscal root is a distinctly different entity than a tear of the meniscus itself and results in the loss of the structure that most robustly holds the meniscus in the normal anatomic position (2). Risk factors for meniscal root tears include female sex, high BMI, greater varus mechanical axis angle, and low levels of exercise (21). This entity seems to be more common than previously thought, with a frequency rate of around 10% (722 of 7148) in patients undergoing knee arthroscopy (22). In the present study, the frequency of medial PMRT was lower than previously reported (22). None of our subjects had a history of knee trauma or arthroscopy, while the earlier study was based on orthopedic patients who had undergone arthroscopic partial meniscectomy, implying that many of the patients had a history of knee trauma and surgical intervention (22).

When the meniscal root is torn, the meniscus can no longer perform its normal function of buffering the mechanical load imposed on the tibiofemoral joint (6). In a recent cadaveric study, a medial PMRT caused a 25% increase in peak contact pressure in the medial compartment compared with an intact meniscus (23). The peak pressure returned to normal when the tear was repaired. There was no difference in peak contact pressure after a total medial meniscectomy and the peak pressure associated with the root tear itself (23). Thus, meniscal root tears seem to have a “pseudomeniscectomy- like” effect.

Meniscal root tears can exist without a tear of the meniscus itself. Our study implies that these two meniscal disruptions have the similar effects on cartilage status. A study by Lee et al (7) reported a very high prevalence of chondral lesions of the medial femoral condyle in knees with medial PMRTs. Their findings are in agreement with a cross-sectional aspect of the present study, but they did not perform a longitudinal analysis.

The association between MR imaging or arthroscopically detected meniscal disease and cartilage loss within the same tibiofemoral joint has been reported (24–26). Moreover, an arthroscopic study showed that, compared with bucket-handle and/or vertical tears of the medial meniscus, root tears were associated with more severe medial tibiofemoral cartilage damage (26). Surgical repair of meniscal root tears varies depending on the exact location and nature of the tear (27), but a relatively young patient with knee OA and an isolated meniscal root tear is likely to benefit from surgical intervention.

Considering the mechanism of degenerative damage to the tissues within the tibiofemoral joint, BMI is an important factor to consider. However, in our study the BMI distribution among the different groups did not notably differ. Moreover, our logistic regression models were always adjusted for BMI, and such adjustments did not alter the associations we observed. Thus, BMI alone is unlikely to explain the increased risk of cartilage loss over time in knees with isolated medial PMRT.

When we stratified our data according to WORMS cartilage grades at baseline, it was shown that a very high proportion of knees with isolated medial PMRT had effusion. However, effusion was also highly prevalent in knees in the meniscal tear group and the no tear group. Since effusion can result from various pathologic mechanisms such as synovitis, ligamentous damage, the status of the meniscal root or meniscus itself is unlikely to solely explain the reason for the observed results.

The intrareader reliability for detection of meniscal root tear was very high in the present study. A likely reason for this high intrareader reliability is that the reader was specifically looking for it in every single case. In routine clinical reading sessions, one does not always expect or look for a meniscal root tear specifically, thereby sometimes missing its presence.

There were several limitations of the present study. The present study included only the medial compartment of the tibiofemoral joint, and thus our findings may not apply to the lateral compartment. In our sample, there were only two knees with isolated lateral PMRT, and meaningful statistical analyses were not possible. However, since the frequency of isolated lateral meniscal root tears is so low, their clinical significance may be questionable. Another limitation is inherent in the nature of the MOST study, which is entirely epidemiologic: Participants are not subject to any surgical intervention in the knee during the study. Thus we could not arthroscopically confirm the definitive presence of the root tear or the exact severity of cartilage damage. Moreover, the sensitivity of the MR imaging protocol used for this study for diagnosis of meniscal abnormalities is not known (19). We included subjects who mostly had baseline radiographically depicted knee OA, and our findings may not be generalized to people without radiographic OA. However, the design of the parent MOST study made it necessary to restrict our subjects to those enrolled in the radiographic OA cohort to minimize selection bias (28). On the other hand, the study sample consisted of patients with relatively stable disease and did not include those with rapidly deteriorating knee arthropathy. This might have created a selection bias if there was a subset of posterior root tears associated with rapid clinical deterioration and severe associated injury. Consequently, we could be underestimating the effect of this injury on subsequent joint deterioration. Last, we did not find any anterior meniscal root tears in our large sample, but that is not surprising since, to our knowledge, tears of the anterior meniscal roots have not been reported in the literature.

In conclusion, in middle-aged and elderly persons with radiographically depicted knee OA, isolated medial PMRT is associated with medial tibiofemoral cartilage loss.

Advance in Knowledge.

• Isolated medial posterior meniscal root tear (PMRT) is associated with development or worsening of medial tibiofemoral cartilage damage.

• Isolated medial PMRT has adverse effects on medial tibiofemoral cartilage integrity similar to a tear or maceration of the meniscus itself.

Implication for Patient Care.

• Isolated medial PMRT without apparent damage to the meniscus itself increases risk of cartilage damage medially.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: A.G. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: received consultancies, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Genzyme, Stryker, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Astra Zeneca and is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab. Other relationships: none to disclose. D.H. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. M.J. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. F.W.R. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: received consultancy fees from Merck Serono and Boston Imaging Core Lab and stock options from Boston Imaging Core Lab. Other relationships: none to disclose. Y.Z. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. J.N. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. M.D.C. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: stock options from Boston Imaging Core Lab. Other relationships: none to disclose. M.E. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. J.A.L. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. M.C.N. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. J.C.T. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. C.E.L. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. D.T.F. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: received consultancy fees from Knee Creations, Inc. Other relationships: none to disclose.

Received November 16, 2012; revision requested January 8, 2013; revision received January 22; accepted February 4; final version accepted February 13.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants U01-AG-18947, U01-AG-18832, U01-AG-19069, U01-AG-18820, and AR47785).

Abbreviations:

- BMI

- body mass index

- MOST

- Multicenter Osteoarthritis

- OA

- osteoarthritis

- PMRT

- posterior meniscal root tear

- WORMS

- Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score

References

- 1.Soames RW. Skeletal system. In: Williams PL, ed. Gray’s anatomy. 38th ed New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone, 1995; 720–724 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenig JH, Ranawat AS, Umans HR, Difelice GS. Meniscal root tears: diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy 2009;25(9):1025–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagnani MJ, Cooper DE, Warren RF. Extrusion of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy 1991;7(3):297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi CJ, Choi YJ, Lee JJ, Choi CH. Magnetic resonance imaging evidence of meniscal extrusion in medial meniscus posterior root tear. Arthroscopy 2010;26(12):1602–1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerer DB, Umans HR, Hu MX, Jones MH. The role of meniscal root pathology and radial meniscal tear in medial meniscal extrusion. Skeletal Radiol 2004;33(10):569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones AO, Houang MT, Low RS, Wood DG. Medial meniscus posterior root attachment injury and degeneration: MRI findings. Australas Radiol 2006;50(4):306–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee YG, Shim JC, Choi YS, Kim JG, Lee GJ, Kim HK. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of surgically proven medial meniscus root tear: tear configuration and associated knee abnormalities. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2008;32(3):452–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SY, Jee WH, Kim JM. Radial tear of the medial meniscal root: reliability and accuracy of MRI for diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;191(1):81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DH, Lee BS, Kim JM, et al. Predictors of degenerative medial meniscus extrusion: radial component and knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19(2):222–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study Operations manual: recruitment and sampling (version 1.0p, May 2009). http://most.ucsf.edu/docs/RecruitSampling1.0pMay2009.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2013

- 11.Anderson JJ, Felson DT. Factors associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in the first national Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES I): evidence for an association with overweight, race, and physical demands of work. Am J Epidemiol 1988;128(1):179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAlindon TE, Wilson PW, Aliabadi P, Weissman B, Felson DT. Level of physical activity and the risk of radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham study. Am J Med 1999;106(2):151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohatsu ND, Schurman DJ. Risk factors for the development of osteoarthrosis of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990. (261):242–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Fithian DC, Rossman DJ, Kaufman KR. Fate of the ACL-injured patient: a prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med 1994;22(5):632–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miranda H, Viikari-Juntura E, Martikainen R, Riihimäki H. A prospective study on knee pain and its risk factors. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2002;10(8):623–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterfy CG, Lynch J, Miaux Y, et al. Non-fluoroscopic method for flexed radiography of the knee that allows reproducible joint-space width measurement [abstr]. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:S361 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957;16(4):494–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma L, Song J, Felson DT, Cahue S, Shamiyeh E, Dunlop DD. The role of knee alignment in disease progression and functional decline in knee osteoarthritis. JAMA 2001;286(2):188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roemer FW, Guermazi A, Lynch JA, et al. Short tau inversion recovery and proton density-weighted fat suppressed sequences for the evaluation of osteoarthritis of the knee with a 1.0 T dedicated extremity MRI: development of a time-efficient sequence protocol. Eur Radiol 2005;15(5):978–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterfy CG, Guermazi A, Zaim S, et al. Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12(3):177–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang BY, Kim SJ, Lee SW, et al. Risk factors for medial meniscus posterior root tear. Am J Sports Med 2012;40(7):1606–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozkoc G, Circi E, Gonc U, Irgit K, Pourbagher A, Tandogan RN. Radial tears in the root of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16(9):849–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus: similar to total meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90(9):1922–1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crema MD, Guermazi A, Li L, et al. The association of prevalent medial meniscal pathology with cartilage loss in the medial tibiofemoral compartment over a 2-year period. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18(3):336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Englund M, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Guermazi A. Meniscus pathology, osteoarthritis and the treatment controversy. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8(7):412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry S, Mascarenhas R, Kowalchuk D, Forsythe B, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD. Medial meniscus tear morphology and chondral degeneration of the knee: is there a relationship? Arthroscopy 2012;28(8):1124–1134, e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vyas D, Harner CD. Meniscus root repair. Sports Med Arthrosc 2012;20(2):86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study Publication Committee Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study knee magnetic resonance imaging assessments (baseline to 15-month and 30-month follow-up WORMS) dataset description and reading protocol. June 2011. http://most.ucsf.edu/docs/DatasetDescription_V012WORMS.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2012