Abstract

Research on caregiving of elders in Mexican American families is urgently needed. We know little about family caregivers, family transitions in relation to the caregiving role, reciprocal impact of caregivers and care recipients on one another, adaptive strategies, positive benefits of caregiving (caregiver gain), specific caregiving burdens, or supportive interventions for family caregiving. Theory derivation using the concepts and structure of life course perspective provides a way to fill the knowledge gaps concerning Mexican American caregiving families, taking into account their ethnic status as an important Hispanic subgroup and the unique cultural and contextual factors that mark their caregiving experiences.

Keywords: Mexican American, life course perspective, elder caregiving

Mexican Americans, the largest ethnic minority in the United States, compose 66% of the Hispanic population in our country. It is estimated that there are more than 42 million Hispanics in the United States (almost 14% of the population), a number that has grown about 60% since 1990 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000). The over-65 cohort will grow faster than any other racial or ethnic group, tripling in number to 13 million by 2050. Thirteen percent of Hispanic households currently provide care to an adult age 50 or older; however, given this imminent and dramatic shift in demographics, a burgeoning number of Hispanic families soon will be placed in a caregiving role (Coon et al., 2004).

Research on caregiving of elders in Mexican American families is urgently needed because little is known about their levels of caregiver burden, defined as the emotional, psychological, physical, and financial weight assumed by caregivers, along with their subjective appraisals of how caregiving affects their lives (Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, 1980; Zarit, Todd, & Zarit, 1986). By 2030, one quarter of the Hispanic population will be 80 or older, an age when the risk of disability, the key factor in nursing home admission, increases dramatically (Espino et al., 2001). An important cause of disability in these vulnerable elders, cognitive impairment, can be predicted by education and occupation, both of which disadvantage Hispanics. Currently, 36.7% of Mexican Americans older than 65 have some evidence of cognitive impairment (Espino et al., 2001) and greater impairment in activities of daily living (ADLs) than their Anglo counterparts (Raji et al., 2005), even at a younger age (Espino, Moreno, & Talamantes, 1993). Behavioral problems associated with this cognitive decline result in increased caregiver burden and strain across all cultures, but differences in social and economic resources and cultural expectations for Mexican American families may preclude seeking formal care and create additional burden (Torti, Gwyther, Reed, Friedman, & Schulman, 2004).

Although these families keep elders at home longer than Anglo families (Espino, Neufeld, Mulvihill, & Libow, 1988; Meyer, 2001), unmanageable cognitive and functional disability may force nursing home admission. Mexican American nursing home residents are much more impaired on all ADLs except bathing, have more mood and cognitive disorders, are 3.5 times more likely to have a stroke diagnosis, and are almost 8 times more likely to be diabetic than their Anglo counterparts (Espino et al., 1988; Espino et al., 1993).

Literature about informal caregivers of older Mexican Americans, or how such caregivers adapt to critical events in the caregiving experience, is limited and much is dated. We do know, however, that caregiving issues are critical for these families because continuing informal care for parents is central to the culture. Caregiving of Hispanic families is complicated by factors such as immigration, acculturation, socioeconomic status, lack of culturally appropriate services (including those that are language specific; Giunta, Chow, Scharlach, & Dal Santo, 2004), and specific cultural guidelines such as those associated with la familia, where the family is the main source of social interaction, transcending socioeconomic status or sex. Additionally, expectations for care may differ greatly among younger caregivers and elders, particularly for older people born in Mexico. Many Mexican American caregivers have not been exposed to the same elder care models their parents knew from their childhoods. Although la familia may require caregiving, these different generational models of care can lead to conflict in caregiving relationships, increasing caregiver burden and burnout (Clark & Huttlinger, 1998).

Mexican Americans are poorly represented in higher socioeconomic categories and disproportionately overrepresented in low educational attainment (Marotta & Garcia, 2003). The Hispanic/Latino poverty rate is 22.5%; 22% work in service occupations, and another 21% are operators and laborers. Only 14% are in managerial and professional occupations (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000), and only 49% own their own homes, as compared to 76% of Anglos (Ready, 2006). Less education (51% of Mexican Americans have a high school education; only 6.9% hold a bachelor’s degree [U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000]), lower status jobs, and high workload may affect caregiver self-care (Devine, Connors, Sobal, & Bisogni, 2003). Current trends away from traditional values as Mexican American families become more acculturated, combined with lower educational and socioeconomic status (qualifications for Medicaid), may increase the number of Hispanic nursing home residents exponentially unless effective informal care interventions can be identified. The purpose of this article is to use theory derivation (Walker & Avant, 2004) to suggest life course perspective, a theory from the social sciences, as a pragmatic framework for exploring underresearched caregiving experiences in Mexican American families.

Theory Derivation: Studying Mexican American Caregivers

Theory derivation is “the process of using analogy to obtain explanations or predictions about a phenomenon in one field from the explanations or predictions in another field” (Walker & Avant, 2004, p. 171). Walker and Avant (2004) note that it requires imagination and creativity to see analogous dimensions of phenomena in two fields of interest and to transpose one’s content or structure to the other. When transposing, the entire structure is moved to the new field and modified to fit it. For example, a theory that permits longitudinal investigation of phenomena in the social sciences could be transposed into nursing, offering a new approach and additional insights for nursing research.

Theory derivation is used to (a) explain and predict phenomena that are poorly understood or (b) identify a framework for investigation when there is no structural way to represent a set of interrelated concepts using extant theory in the discipline (Walker & Avant, 2004). If a useful structure can be found in another field or discipline, it can be adapted to fit the concepts to add to the body of knowledge. Walker and Avant’s steps for theory derivation include the following:

becoming thoroughly familiar with the literature on the phenomenon in one’s own field so that any relevant theories, if present, can be identified and used to guide investigation;

if such theories are absent, reading widely in other fields with an imaginative and creative eye to discover analogies;

selecting a theory that invites adaptation in content or structure, or both, and offers a new and insightful look at the phenomenon;

identifying content or structure that can be transposed; and developing, refining, or modifying content or structure so that it becomes meaningful for investigation of the phenomenon in the new field.

The process of theory derivation is particularly well suited for addressing the poorly understood caregiving experiences of Mexican American families because it lends itself to the rapid development of knowledge in areas where few data are available (Walker & Avant, 2004).

It also enables identification of a temporal structure (an investigational framework) that does not exist in nursing but can accommodate a set of interrelated caregiving concepts (Walker & Avant). Nursing commonly uses stage theories to study the caregiving process, assigning individuals to a category with others who share the attributes that define that stage. Stages, however, are merely theoretical constructs. Few people will match the prototypical definitions of stages, and in fact, some stage theorists even fail to accommodate developmental changes across the life span. Complicating the use of stage theory is that, because people become increasingly heterogeneous as they age, they are even less likely to fit into a circumscribed category. Stage theories also assume that people progress through stages in an invariant, hierarchical sequence; the large “boxes” to which individuals are assigned may obscure small, common shifts in behavior that could provide vital data about the caregiving process.

Often used in cross-sectional studies at a single point in time, stage theories cannot capture the complexity of caregiving or the aging process, set within the context of the family and the cultural context of aging. Both caregiving and aging (which begins at birth) are gradual, intricate processes of adapting to biological and contextual changes over time through use of culturally based knowledge to compensate for functional decline and maintain well-being (Hazuda, Gerety, Lee, Mulrow, & Lichtenstein, 2002). To study such multifaceted processes, a dynamic paradigm is needed that takes into account individual yet intertwined life courses with various levels of human agency and opportunity, over time, where relationships unite people into groups that are affected by history and culture.

Theories commonly used in nursing to study ethnically and culturally diverse groups include Leininger’s (2001) Culture Care Diversity and Universality and Purnell & Paulanka’s (2003) Model for Cultural Competence. Although detailed and comprehensive in their explication of the domains and dimensions of culture, concepts relating to culture, and the role of nursing in providing culturally competent care, these models provide only cross-sectional snapshots of caregiving in Mexican American families. They do not include the key concept of temporality and therefore do not allow a longitudinal assessment of continuity and change in caregiving across the life span. Life course perspective, however, draws attention to and integrates complex life pathways, family relationships, social and cultural factors, and the interconnectedness of one’s life trajectory with others’ lives and developmental trajectories, as seen over time (Turner, Killian, & Cain, 2004). It addresses the temporal importance of experiences and adaptations to life course transitions such as changes in roles or responsibilities, states of health that develop and persist over time, concomitant social and cultural factors, and decision points where life takes a fateful turn, often with striking consequences. It provides a temporal, historical context for such decisions that shape the trajectory of life and allows consideration of cumulative health advantages or disadvantages (Wethington, 2005). In short, it allows researchers to “understand how group differences in health, health behaviors, and mortality come about and persist across time … and how the accumulation of advantage and disadvantage across the life course affects health status in later life” (Wethington, 2005, p. 118).

Utility of the Life Course Perspective in Studying Caregiving in Mexican American Families

One way to examine the complex processes of caregiving of aging adults is through life course perspective. Although nursing literature uses this approach infrequently, life course perspective is widely used in the social sciences, where it is the leading theoretical orientation for longitudinal study of health and behavior patterns. Its particular strength is a powerful set of cross-disciplinary organizing concepts that can be used for intensive study of family caregiving across time (Wethington, 2005).

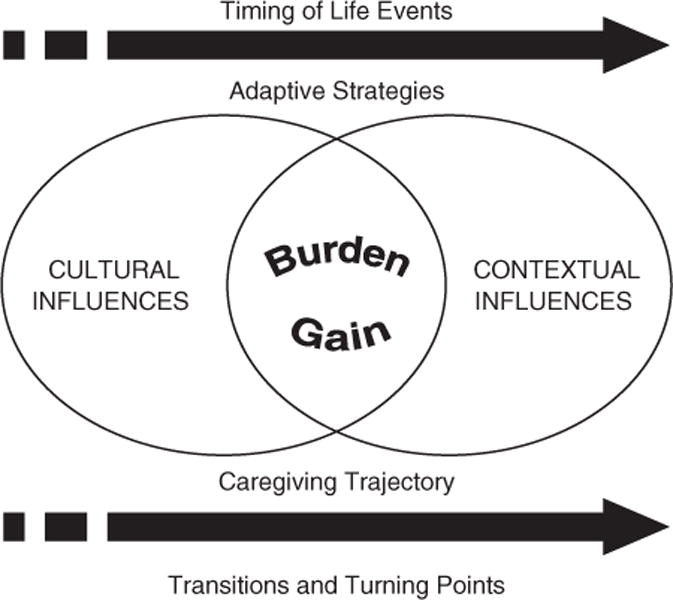

The major theoretical innovation of this approach is that life course perspective allows for the temporal integration of a variety of explanations for differences in caregiver burden and gain (positive aspects of the caregiving role), including cultural and contextual influences. Life course perspective research uses a set of related concepts designed to facilitate derivation of testable hypotheses: trajectories, transitions, turning points, timing, adaptive strategies, and cultural and contextual differences (Wethington, 2005). Family caregiving, with all its attendant influences, decisions, and events, can be plotted visually on a timeline representing the life course trajectory. For example, to capture the progression of events across the full trajectory, we can visualize the very beginning of the caregiving trajectory, the “point of reckoning” when caregiving is recognized and accepted by the caregiver; the well-established caregiving trajectory with transitions and turning points; and the extended trajectory where nursing home admission may be contemplated.

Figure 1 depicts relationships between these concepts, as applied to the experience of the caregiving trajectory.

Figure 1.

Life Course Perspective: Caregiving Trajectory

Contributions of the Life Course Perspective to the Study of Mexican American Caregivers

Using theory derivation, we can transpose the concepts of trajectory, transition, turning point, timing, adaptive strategies, and cultural and contextual differences from life course perspective, a theory from the social sciences, using its temporal orientation in the discipline of nursing to explore underresearched caregiving experiences in Mexican American families.

What nursing knows about caregiving in Mexican American families is complicated by inconsistent results from existing cross-sectional studies. For example, Barber (2002) finds that Hispanic caregivers have slightly lower levels of burden than Anglos, but Garcia (1999) reports higher burden in Hispanics. Additionally, few studies examine the familial, social, and cultural factors that determine who will act as caregivers for older Hispanic family members or describe their experiences (Clark & Huttlinger, 1998). Meta-analyses completed in 1996 and 1997 (Bourgeois, Schulz, & Burgio, 1996; Aranda & Knight, 1997) demonstrated that Hispanic representation in caregiving studies, if present at all, was usually less than 15% of the sample and that, of 12 studies that included minority caregivers, only 2 included Hispanics. There also is little mention of such caregivers in intervention research. Data on the Hispanic subgroup of Mexican Americans are even more limited because some studies fail to conduct subanalysis of data collected from Mexican Americans from other Hispanic subgroups, or samples are small, rendering conclusions inapplicable. Other projects report subgroup data, but participants may be dissimilar to Mexican Americans living in border regions such as Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, making generalization of findings difficult. Additionally, almost all studies focus on negative effects of caregiving (caregiver burden), ignoring the benefits received when caregivers act in accordance with cultural norms (caregiver gain). None of these studies, however, have a temporal orientation. Theory derivation using the concepts and structure of life course perspective provides a way to fill the knowledge gaps concerning Mexican American caregivers, taking into account their status as an important Hispanic subgroup and the unique cultural and contextual factors that mark their caregiving experiences (Walker & Avant, 2004).

Trajectory

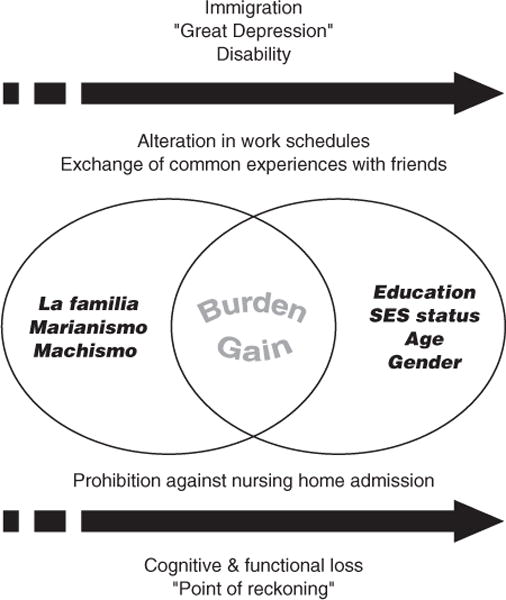

In the social sciences, trajectory refers to patterns of health status or health behavior, persisting over time, and factors that may be associated with health, such as the social network. Such patterns develop in consistent ways, reinforce each other, and are interconnected across other people’s lives and developmental trajectories. In Mexican American families, caregiving of elders is seen as a natural part of life, although that may change with acculturation and its attendant stressors. Despite an extensive literature search, no studies could be found that used the concept of trajectory, set within a life course perspective, to explore caregiving in Mexican American families. Lack of available data in this area creates a fertile opportunity for the use of theory derivation (Walker & Avant, 2004). Figure 2 illustrates the use of life course perspective as applied to the caregiving trajectory of elders in Mexican American families.

Figure 2.

Life Course Perspective: Mexican American Caregiving Families

Transitions and turning points

For sociologists, psychologists, and experts in the fields of education, public health, and medicine, transition is defined as an alteration in social, job, or family roles and responsibilities that may be incorporated into an ongoing trajectory as a gradual change (Wethington, 2005). Transitions may be stressful, especially if unexpected, and lead to demands that overwhelm coping. However, they also may be positive, providing rewards or validating past experiences. Transitions are common and those affecting one’s social role also may affect other trajectories, such as health and lifestyle habits. For the elder care recipient, transitions may include gradual loss of cognitive or functional abilities that leads to a turning point such as nursing home admission.

Little research has been done in nursing on how family caregiver health affects older care recipients of any cultural or ethnic group (Lyons, Sayer, Archbold, Hornbrook, & Stewart, 2007), although Archbold et al. have published cross-sectional descriptions of differences in demographic characteristics, predictors of role strain, coping strategies, and levels of burden across cultures (e.g., Nkongho & Archbold, 1996; Shyu, Archbold, & Imle, 1998). Despite the fact that her team refers to “transitions” and “trajectories” (Archbold et al., 1995; Lyons et al., 2007; Lyons, Stewart, Archbold, Carter, & Perrin, 2004; Lyons & Sayer, 2005a, 2005b), they have not yet applied those concepts in the longitudinal context of life course perspective. Also, the Archbold team focuses primarily on Anglo populations, representative of the population of the Pacific Northwest. Exploration of caregiving in Mexican American populations using a life course perspective framework is a logical extension of their impressive body of work that will illuminate the portion of the caregiving trajectory in which Mexican American families, in particular, make the decision to continue caregiving or relinquish their family member to a nursing home.

Critical transitions in the life course occur in regard to marital status, childbearing, and mortality. Changes in life expectancy and death rates affect the timing and duration of transitions, such as the age of widowhood and the caregiving period for elders. Caregiver age at marriage, age at birth of first and last child, and age when the last child leaves home seem to be of particular importance when studying Mexican American elders who tend to coreside with others and require intergenerational care. Developmental transitions such as these often provide context for dawning acknowledgement of a future caregiving role and efforts to merge one’s understanding of that role with already established roles, such as daughter or niece (Escandon, 2006). However, we know little about transitions in Mexican American families in relation to the caregiving role, or the reciprocal impact of caregivers and care recipients on one another.

Turning points are defined as less common, major transitions where life is perceived as having taken a fateful turn and trajectories are broken. Turning points involve decisions about future commitments or life paths, are usually identified retrospectively (Wethington, 2005), and may be influenced by caregiver gain, the positive effect of the caregiving situation on the Mexican American family (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2004). One turning point identified by Mexican American caregivers is the “point of reckoning” (Clark & Huttlinger, 1998) or “point of no return” (Escandon, 2006) in which the caregiver accepts primary responsibility for caregiving, modifying his or her life as a result of a significant event such as an elder’s need for increased assistance. Even an elder’s diminishing ability to deal with the English language or interact with the Anglo world may precipitate this fateful turn (Phillips, de Ardon, Komnenich, Killeen, & Rusinak, 2000). The “point of reckoning” is accompanied by the loss and grieving of the child or spouse role that has previously characterized the relationship. Such turning points are often precipitated by stress and frustration associated with trying to meet job, family, and elder care demands simultaneously.

The discipline of nursing is currently unable to provide a theoretical framework that allows simultaneous consideration and integration of the complex relationships between patterns of health and health behaviors, alteration in roles and responsibilities, transitions and turning points such as marital status, and intergenerational factors across the trajectory of the caregiving experience. Theory derivation allows use of a powerful framework from the social sciences to represent these multiple relationships within the context of nursing research (Walker & Avant, 2004).

Timing of life events and adaptive strategies

Social scientists study the timing of life events such as immigration or the Great Depression that may have long-lasting effects on caregivers and their adaptive strategies. Individuals may have very different reactions to the timing and import of such events, a response that is partly shaped by social class. Ten million Mexican Americans living in the United States today were born in Mexico (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000). For these individuals, the life course timing of immigration entails various, momentous socioeconomic issues that affect their future decisions and, by proxy, those of their families. Recency of immigration also influences the number of social ties, which increase with length of stay in the United States; those newly immigrated may be vulnerable to stress because of smaller family networks (Aranda & Knight, 1997; Phillips et al., 2000).

Adaptive strategies are defined in the social sciences as conscious decisions to change, based on social or cultural norms affecting the ways in which such decisions are made. Such strategies may be developed over time as responses to severe stress faced by disadvantaged minorities (Aranda & Knight, 1997). Mexican American adult children often assume the caregiving role earlier than their Anglo counterparts, perhaps because of the children’s tendency to protect their aging mothers (Phillips et al., 2000). Although we know little about other adaptive strategies in the caregiving trajectory of Mexican American families, Hazuda et al. (2002) did identify physical (35%), cognitive (13%), affective (12%), social (31%), and environmental (9%) adaptive changes in such families in response to increasing disability in elder care recipients.

Adaptive strategies are vital for adult Mexican American children who often are expected to provide care regardless of whether a spouse is available (Phillips et al., 2000). In general, daughters, wives, or daughters-in-law are likely to be primary caregivers and provide more hands-on hours of care than sons or husbands, who tend to provide help with activities such as money management and help around the house. Forty-seven percent of female Hispanic caregivers also are responsible for children in the home (Giunta et al., 2004), and increasingly, such caregivers are single women who work at an outside job as well (Torti et al., 2004). Caring for their aging parent or a spouse, however, requires a different set of adaptive strategies than caring for children, whose needs decrease over time (Clark & Huttlinger, 1998).

Adaptive strategies, however, may not be effective. Female Mexican American caregivers report higher levels of depression than males. In one study examining acculturation, caregiver burden, and family support in Hispanic women, almost half were depressed; depression was significantly related to dissatisfaction with family support in more acculturated caregivers (Polich & Gallagher-Thompson, 1997). Other recent work with 48 Hispanic caregivers (female and male) found that la familia had a protective effect against perceived burden. In this study, acculturation did not directly relate to perceived burden or depression but had indirect effects on depression through familism and perceived burden (Robinson-Shurgot & Knight, 2005). Effect sizes for associations between acculturation, familism, burden, and depression were approximately .30 or greater, a medium to large effect size, and power was .55 or greater.

Caregiver gain may be similar across various ethnic caregivers who feel useful and see themselves as able to handle difficult situations, set an example for their children, and fulfill their cultural obligations (Giunta et al., 2004). Mexican American caregivers with friends or other family members engaged in caregiving may exchange common experiences, foster feelings of solidarity, and view caregiving more positively (Escandon, 2006; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2004). They may express a need for reciprocity, for provision of physical and emotional support, and for paying back their debts to elders (Clark & Huttlinger, 1998). They accept elders for both who they are and who they were, and they view caregiving as normative, which strengthens their long-term commitment and affirms familial responsibility and the bond with the elder. If Mexican American women judge caregiving as normative and as strengthening social continuity, they tend to view it in a positive light and have greater role satisfaction. However, the more acculturated these women are, the less likely they are to hold such positive views and the more likely they are to admit elders to nursing homes (Phillips et al., 2000).

We need rapid knowledge development (Walker & Avant, 2004) concerning the effect of tumultuous life events such as immigration and ways in which rapidly acculturating Mexican American families adapt, or struggle to adapt, to these events and the demands of caregiving. To accomplish this task, we need more than one data “snapshot” in time, and we need detailed information about individuals’ responses to events, in the context of social class, an approach that is afforded by life course perspective.

Cultural and contextual influences

Scientists who study health and health behavior across the life course define cultural and contextual influences as historical or individual events from childhood or young adulthood that shape the caregiving trajectory. Also included in their definition is the notion that persistent, cumulative advantages or disadvantages of socioeconomic status accrue, affecting health as people age (Wethington, 2005). In their view, socioeconomic status (years of education, current income, and occupation), race, age, and gender all affect the caregiving trajectory.

Mexican Americans may be particularly at risk for cumulative health disadvantages and health disparities because of ethnicity, class, and immigration status. They are poorly represented in higher socioeconomic categories and disproportionately overrepresented in low educational attainment (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000). Less education (51% of Mexican Americans have a high school education; 6.9% hold a bachelor’s degree), lower status jobs, and high workload may affect caregiver self-care and mold individuals’ explanatory models (sets of explanations about disease and illness), which affect caregiver response to elder care recipients.

Role strain may be greater for families from lower socioeconomic groups who hold unskilled and service jobs without employee benefits such as health insurance, sick leave, or even access to telephones to arrange for elder care (Aranda & Knight, 1997). Such factors, combined with language barriers, can result in lack of awareness of outside resources and lack of use of formal services that could ease caregiver burden (Giunta et al., 2004).

When studying the caregiving trajectory in Mexican American families, it is vital to acknowledge cultural prohibitions against nursing home admission, even in the face of their uncertainty about their ability to continue informal caregiving (Escandon, 2006). Although their specific caregiving burdens remain to be documented, simply belonging to an ethnic group predicts differences in caregiving burden, depression, use of formal services, and physical health (Aranda & Knight, 1997; Coon et al., 2004). Such differences are thought to be critical elements in the decision to care for elders at home, particularly for more traditional caregivers—that is, those who are less acculturated (Torti et al., 2004).

Spirituality appears to provide a durable, substantial foundation for coping with caregiving struggles in Mexican American families. Spirituality is conceptualized quite differently by such families than it is by Anglos. It is not an autonomous search for meaning in life but rather a personal and collective responsibility for self, family, and community that is woven into one’s daily life (Campesino & Schwartz, 2006). According to Campesino, Mexican Americans merge Roman Catholicism religious symbols with their indigenous cultural roots, reflecting the colonization and subjugation of Mexico by European Christians. Modern Mexican American women express this fusion in the form of “popular religiosity,” in which they exemplify the traditional cultural values of personalismo (characterized by warmth, affection, and empathy) and familismo (marked by an enduring connection and commitment to family) in their intimate, active, everyday relationships with God, the Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Guadalupe, and the saints (Campesino & Schwartz, 2006). These affectionate, devoted, personal relationships offer opportunities to speak intimately with religious figures about caregiving problems, just as one would converse with a trusted friend. The result is that even third- and fourth-generation Hispanics rely heavily on their spirituality as an important resource in caregiving.

Theory derivation using life course perspective promotes understanding of these families and of the power of spirituality and la familia, which influence elder care in Mexican American families, providing strong support and intergenerational reliance. Elders, who play an important role in the family, rely primarily on family members for help with financial, medical, or personal problems (Clark & Huttlinger, 1998). Families feel a strong moral obligation to unconditionally help and care for parents, grandparents, or spouses (including physical and emotional support; Clark & Huttlinger, 1998). Hispanic caregivers are almost twice as likely to reduce work hours or quit work to provide care as Anglos (Odds Ratio = 1.90, 95% Confidence Interval = 1.43 to 2.52; Covinsky et al., 2001).

Analogies Between the Life Course Perspective and the Caregiving Trajectory in Mexican American Families

Understanding individual lives in changing contexts over time is fundamental to both life course perspective and the caregiving trajectory for Mexican American families. Elements of life course perspective lend structure to exploring the experiences of such families who operate within a constantly changing social, cultural, and environmental context that includes immigration and acculturation. Content for these explorations also is provided by life course delineation of such concepts as transition and turning point and elucidation of the dynamic relationships between them. Examples of analogies between these concepts, structured by life course perspective and applied to the Mexican American caregiving trajectory, are set forth in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of Analogies Between the Life Course Perspective and the Mexican American Caregiving Trajectory

| Concept | Life Course Perspective | Derived Concept | Examples in the Mexican-American Caregiving Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory | Health, social, and other trajectories in one’s life tend to develop together in consistent ways that reinforce each other and remain stable over time. | Caregiving trajectory | The caregiving trajectory for Mexican American families, although underresearched, should unfold over time in ways consistent with the social trajectory already established with relatives and friends. |

| Transitions | Transitions are significant changes in social roles or in responsibilities of an existing role, often accommodated into a trajectory as a gradual change. | Caregiving transitions | Case in point: When abuelita (little grandmother) grows increasingly confused, adult children adjust by altering their work hours so that someone is always home to act as caregiver. |

| Turning points | Transitions may be of sufficient magnitude to cause a break in the life course trajectory: life takes a fateful turn. | Reckoning points | Caregivers, many of whom work outside the home, may come to a “reckoning point” where they accept responsibility for caring for an aging or disabled parent because there is no one else to do it. |

| Timing of life events | Health is affected by accumulated disadvantage in the interaction between early-life and later-life social, behavioral, and environmental factors. | Timing of caregiving | Many older adults who emigrated, worked in low-paying jobs, and had little health care are more disabled at younger ages than Anglos yet continue to be cared for at home. |

| Adaptive strategies | Adaptive strategies are templates that guide the interaction between the context and culture of a group and the conscious decisions that one makes to adjust to external events. | Caregiving strategies | The need for reciprocity for their own caregiving as children compels commitment to caregiving of elders, even though privacy and family life with a spouse and children may be compromised. |

| Cultural and contextual influences | Cultural and contextual influences in childhood and adolescence affect adaptive strategies and health across the lifespan. | Caregiving in la familia | Age, gender, spirituality, and socioeconomic status shape the caregiving trajectory through social norms or expectations for behavior in la familia. |

Source: Adapted from Wethington (2005).

Implications for Research

Little is known about ways to support the caregiving trajectory of elders in the Mexican American population, and much of what is known addresses care recipients’ perspectives rather than caregivers’. A life course perspective could assist researchers and practitioners in integrating explanations of group and individual patterns of health and health behavior, along with other individual factors such as personal preferences, in dynamic ways that accommodate the passage of time (Wethington, 2005).

We know even less about how to support the caregiving trajectory of Mexican American male caregivers. Currently, because of taboos in regard to personal care by Hispanic males of female relatives, particularly mothers, most males help with such tasks as cooking and medication management but cannot bathe or toilet female elders. Others, however, have no choice because there is no one else to do it. Traditionally, males rarely act in that capacity (Clark & Huttlinger, 1998), but one recent study demonstrated that more Hispanic husbands than daughters-in-law (14.6% and 6.3%, respectively) were caregivers (Robinson-Shurgot & Knight, 2005). Whatever their caregiving role, however, males remain as primary decision makers, and family conflict may result when daughters or daughters-in-law try to step in as caregivers. Theory derivation could lead to important knowledge about the evolving caregiving roles of Mexican American men in present-day society so that nurses could better support them as they embark on this dramatic cultural shift.

Life course perspective also offers the opportunity to study the role of marianismo in the caregiving trajectory of Mexican American females. Marianismo teaches rules for saintliness and goodness that are modeled on the suffering of the Virgin Mary, thereby shaping the socialization process of Hispanic girls. Such rules, however, must be balanced by a sense of dignity and nobility (Arredondo, 2002). Marianismo can create conflict in the female caregiver because seeking outside help may be seen as undignified. She may be caught between self-sacrifice, faithfulness, and subordination to one’s husband, which preclude seeking help and acknowledging her own needs for caregiving assistance. Although many Mexican American women accept the subservient role traditionally associated with marianismo, others have reinterpreted the role as a symbol of dignity and strength. Because marianismo is reinforced by machismo in Mexican American males, this modern reinterpretation can result in family conflict, with unpredictable results.

Life course perspective could address these underresearched areas through intensive, longitudinal exploration of the caregiving trajectory in Mexican American families. Examination of transitions (changes in responsibilities) in the trajectory (pattern of behavior across time) of the caregiving experience, turning points (major transitions where life takes a different direction) to which caregivers must respond in light of cognitive or functional decline of care recipients and caregivers, would offer a greatly increased understanding of their caregiving concerns.

In summary, life course perspective offers a means of understanding caregiving in Mexican American families, a significant issue because of the rapidly changing demographics of the Mexican American population, increasing levels of disability in elders, and gradual acculturation that results in Mexican American families who are less able or willing to continue informal care. Gerontologists should prepare themselves to address the health issues of this group, the fastest growing population in the country, whose life expectancy will increase to 87 years by 2050, surpassing all other ethnic groups (Espino et al., 2001; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000). Using life course perspective as a theoretical framework, nurse researchers could state propositions and test theory in future research by retrospectively examining critical landmark events in Mexican American caregiving trajectories to generate reliable data and hypothesizing and testing predictions of difference in trajectories throughout the course of a caregiving lifetime. Additionally, systematic research that examines the trajectory of caregiving could prove useful in clinical practice by guiding the design of evidence-based interventions (timed so as to occur simultaneously with transitions and turning points) to keep elders at home longer or to help families acknowledge when formal nursing home care should be sought.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Lorraine Walker, University of Texas at Austin, and Drs. Julie Fleury and Kathryn Records, Arizona State University College of Nursing and Healthcare Innovation, for their kind and expert assistance with preparation of this article.

Contributor Information

Bronwynne C. Evans, Arizona State University.

Neva Crogan, University of Arizona.

David Coon, Arizona State University.

References

- Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. Gerontologist. 1997;37(3):342–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archbold P, Stewart B, Miller L, Harvath T, Greenlick M, Van Buren L, et al. The PREP system of nursing interventions: A pilot test with families caring for older family members. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18:3–16. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo P. Mujeres latinas—Santas y marquesas. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8(4):308–319. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber CE. A comparison of Hispanic and non-Hispanic white families caring for elderly patients. Gerontological Society of America; Boston: 2002. Nov, Paper presented at 55th Annual. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois MS, Schulz R, Burgio L. Interventions for caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A review and analysis of content, process, and outcomes. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 1996;43(1):35–92. doi: 10.2190/AN6L-6QBQ-76G0-0N9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campesino M, Schwartz G. Spirituality among Latinas/os: Implications of culture in conceptualization and measurement. Advances in Nursing Science. 2006;29:69–81. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200601000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M, Huttlinger K. Elder care among Mexican American families. Clinical Nursing Research. 1998;7(1):64–81. doi: 10.1177/105477389800700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon D, Rubert M, Solano N, Mausbach B, Kraemer H, Arguëlles T, et al. Well-being, appraisal, and coping in Latina and Caucasian dementia caregivers: Findings from the REACH study. Aging & Mental Health. 2004;8(330):345. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001709683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui LY, Sands LP, Sehgal AR, Walter LC, et al. Reduced employment in caregivers of frail elders: Impact of ethnicity, patient clinical characteristics, and caregiver characteristics. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2001;56(11):M707–M713. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.11.m707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Connors MM, Sobal J, Bisogni CA. Sandwiching it in: Spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate-income urban households. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(3):617–630. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escandon S. Mexican American intergenerational caregiving model. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2006;28(5):564–585. doi: 10.1177/0193945906286804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino D, Moreno C, Talamantes M. Hispanic elders in Texas: Implications for health care. Texas Medicine. 1993;89(10):58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino DV, Mouton CP, Del Aguila D, Parker RW, Lewis RM, Miles TP. Mexican American elders with dementia in long term care. Clinical Gerontologist. 2001;23(3/4):83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Espino DV, Neufeld RR, Mulvihill M, Libow LS. Hispanic and non-Hispanic elderly on admission to the nursing home: A pilot study. Gerontologist. 1988;28(6):821–824. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.6.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia EM. Caregiving in the context of ethnicity: Hispanic caregiver wives of stroke patients. University of California; Irvine: 1999. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta N, Chow J, Scharlach A, Dal Santo T. Racial and ethnic differences in family caregiving in California. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2004;9(4):85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hazuda HP, Gerety MB, Lee S, Mulrow CD, Lichtenstein MJ. Measuring subclinical disability in older Mexican Americans. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64(3):520–530. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M. Culture care diversity and universality: A theory of nursing. Boston: Jones & Bartlett; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons K, Sayer A. Longitudinal dyad models in family research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005a;67:1048–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons K, Sayer A. Using multilevel modeling in caregiving research. Aging & Mental Health. 2005b;9:189–195. doi: 10.1080/13607860500089831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons K, Sayer A, Archbold P, Hornbrook M, Stewart B. The enduring and contextual effects of physical health and depression on care-dyad mutuality. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30:84–98. doi: 10.1002/nur.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons K, Stewart B, Archbold P, Carter J, Perrin N. Pessimism and optimism as early warning signs for compromised health for caregivers of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Nursing Research. 2004;53(6):354–362. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta SA, Garcia JG. Latinos in the United States in 2000. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25(1):13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MH. Medicaid reimbursement rates and access to nursing homes: Implications for gender, race, and marital status. Research on Aging. 2001;23(5):532–551. [Google Scholar]

- Nkongho N, Archbold P. Working-out caregiving systems in African-American families. Applied Nursing Research. 1996;9:108–114. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(96)80194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips L, Torres de Ardon E, Komnenich P, Killeen M, Rusinak R. The Mexican American caregiving experience. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2000;22(3):296–313. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Associations of caregiver stressors and uplifts with subjective well-being and depressive mood: A meta-analytic comparison. Aging & Mental Health. 2004;8(5):438–449. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001725036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich T, Gallagher-Thompson D. Preliminary study investigating psychological distress among female Hispanic caregivers. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 1997;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Purnell L, Paulanka B. Transcultural health care: A culturally competent approach. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Raji MA, Kuo YF, Snih SA, Markides KS, Peek MK, Ottenbacher KJ. Cognitive status, muscle strength, and subsequent disability in older Mexican Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(9):1462–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ready T. Hispanic housing in the US. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame, Institute for Latino Studies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Shurgot GS, Knight BG. Preliminary study investigating acculturation, cultural values, and psychological distress in Latino caregivers of dementia patients. Hispanic Health Care International. 2005;3(1):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shyu Y, Archbold P, Imle M. Finding a balance point: A process central to understanding family caregiving in Taiwanese families. Research in Nursing & Health. 1998;21:261–270. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199806)21:3<261::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torti FM, Jr, Gwyther LP, Reed SD, Friedman JY, Schulman KA. A multinational review of recent trends and reports in dementia caregiver burden. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2004;18(2):99–109. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000126902.37908.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Killian T, Cain R. Life course transitions and depressive symptoms among women in midlife. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2004;58(4):241–265. doi: 10.2190/4CUU-KDKC-2XAD-HY0W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Census 2000. Washington DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walker L, Avant K. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. 4. Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Lange; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E. The life course perspective on health: Implications for health and nutrition. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2005;37:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit S, Todd P, Zarit J. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: A longitudinal study. Gerontologist. 1986;26(3):260–266. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]