Abstract

Although many studies show that pulmonary Surfactant Protein A (SP-A) functions in innate immunity, fewer studies have addressed its role in adaptive immunity and allergic hypersensitivity. We hypothesized that SP-A modulates the phenotype and prevalence of dendritic cells (DCs) and CD4+ T cells to inhibit Th2-associated inflammatory indices associated with allergen-induced inflammation. In an ovalbumin (OVA) model of allergic hypersensitivity, SP-A deficient (SP-A−/−) mice had greater eosinophilia, Th2-associated cytokine levels, and IgE levels compared to wild-type (WT) counterparts. Although both OVA-exposed groups had similar proportions of CD86+ DCs and Foxp3+ T regulatory cells, the SP-A−/− mice had elevated proportions of CD4+ activated (TA) and effector memory (TEM) T cells in their lungs compared to WT mice. Ex vivo recall stimulation of CD4+ T cell pools demonstrate that the cells from the SP-A−/− OVA mice had the greatest proliferative and IL-4 producing capacity, and this capability was attenuated with exogenous SP-A treatment. Additionally, tracking proliferation in vivo demonstrated that TA and TEM cells expand to the greatest extent in the lungs of SP-A−/− OVA mice. Taken together, our data suggest that SP-A influences the prevalence, types, and functions of CD4+ T cells in the lungs during allergic inflammation and that surfactant protein deficiency modifies the severity of inflammation in allergic hypersensitivity conditions like asthma.

Keywords: Rodent, T cells, Allergy, Inflammation, Lung

INTRODUCTION

Lung surfactant is a lipoprotein complex that both reduces surface tension at the air-liquid interface and participates in host defense. One of its protein components, surfactant-associated protein (SP)-A, is a member of the collectin family of innate immune molecules, and as such, functions in host defense against a variety of inhaled microbial pathogens by acting as an opsonin (reviewed in (1–3)) and by regulating immune cell function (3–5).

In comparison to our understanding of the role of SP-A in innate immunity and infectious disease models (6–9), relatively little is known about the role of SP-A in allergic hypersensitivity conditions such as atopic asthma, where increasing prevalence and related health complications are a top reason for absenteeism from school and work in the U.S. (10). Mounting evidence suggests that SP-A plays a protective role in allergic hypersensitivity, and that this protection is attenuated in conditions where SP-A levels are lowered or where SP-A is inactivated (11–15). Previously, we have shown in vitro that SP-A modulates the functions of two adaptive immune cells that play critical roles in asthma pathogenesis. Specifically, SP-A inhibits T cell proliferation in an accessory cell independent manner and inhibits dendritic cell (DC) maturation and their ability to subsequently stimulate T cell proliferation (16, 17). In addition, other reports have shown that SP-A inhibits the in vitro proliferation of antigen-stimulated human PBMC (18), of murine splenocytes co-cultured with ovalbumin-specific T cell hybridomas (17), and of sensitized murine splenocytes to Aspergillus fumigatus (Afu) re-challenge (12). Administration of SP-A in Afu-treated mice has been shown to attenuate eosinophilia and cytokine production (19). Taken together, these studies suggest that SP-A functions as a dynamic link between innate and adaptive immunity and may be an important regulator of inflammatory consequences associated with allergic lung disease.

DCs and T cells are critical inducers and mediators of adaptive immune responses. Immature DCs are primarily phagocytic and exposure to inhaled allergens normally results in a state of tolerance by producing anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 or stimulating suppressive activity of T regulatory (TREG) cells (20, 21). Upon antigen challenge, DCs undergo a maturation process as evidenced by increased expression of MHC Class II (MHCII) and co-stimulatory molecules CD86 and CD80, which allow for effective antigen presentation to T cells in regional lymph nodes or locally in tissue (22, 23).

CD4+ T cells are a heterogeneous population, endowed with different migratory capacities and effector functions. Naïve T cells (TN) are thought to have not yet encountered cognate antigen and to have high surface expression of the lymph node–homing receptor L-selectin (CD62L) and low expression of the memory cell marker CD44 (24, 25). Upon recognition of its cognate antigen, the TN cell acquires an activated phenotype (TA) with reduced CD62L expression. These cells may then further differentiate into memory cells. Memory cells can be divided into central memory T cell (TCM) and effector memory T cell (TEM) subsets. TCM cells express CD62L and lack immediate effector function; however, upon restimulation in secondary lymphoid organs, they proliferate and differentiate into effector cells (26). TEM cells lack CD62L and express receptors for migration into inflamed tissue. Upon re-encounter with antigen, these cells have immediate effector function and can rapidly produce inflammatory mediators such as Th2-associated cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 (27). Naturally-occurring TREG cells, which constitutively express the α-chain of the IL-2 receptor CD25 and the intracellular transcription factor Foxp3, can inhibit DCs from initiating Th2-driven responses and suppress Th2 effector cell function (28–30). Failure of TREG cells to limit the activity of immune cells implicated in asthma may contribute to the development of the disease (31). In the asthmatic condition effector CD4+ T cells accumulate in the lung and perpetuate a Th2 pattern of inflammation. Increased numbers of activated T cells in people with asthma typically correlate with the numbers of activated eosinophils, the levels of cytokines IL-4 and IL-5, the magnitude of decrement in peak expiratory flow rates, and severity of the disease (32, 33).

The lungs are continuously exposed to a barrage of environmental irritants that challenge the tight regulation between an active immune defense and tolerance. We hypothesized that SPA, as part of the local microenvironment of the lung, is critical in modulating the phenotype and prevalence of DCs and CD4+ T cells to inhibit characteristic Th2-associated inflammatory indices associated with allergen-induced inflammation. We combined the use of SP-A deficient mice, the well-characterized OVA-driven model, and in vivo and ex vivo functional assays that used lung-derived cells to examine the dynamic link between innate and adaptive immunity mediated by SP-A.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and OVA-alum model of allergic asthma

SP-A−/− mice were backcrossed for 12 generations onto a C57BL/6 background. Age- and sex-matched control C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) or Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Experimental protocols were approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were carried out in accordance with the standards established by the U.S. Animal Welfare Acts. Mice (6–8 wks) were sensitized on Days 0 and 14 by i.p. injections of 0.1 ml saline containing 10 μg OVA (Grade V, Sigma-Aldrich) complexed with 2.0 mg Imject Alum (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). On days 21–23, mice were exposed to 1% aerosolized OVA in sterile saline for 20 min in a 60 L Hinner exposure chamber connected to an ultrasonic nebulizer that delivers aerosol particles with 0.6 – 0.7 μm mean diameter (DeVilbiss Ultra-Neb, replaced by Nouvag Ultrasonic 2000, Susquehanna Micro, Inc., PA). Sham mice were given i.p. injections of Alum/saline and were aerosolized with saline. Animals were euthanized and tissue samples were harvested 24 h after the last aerosol challenge. All OVA preparations had an average endotoxin concentration of 70 EU/mg using the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (QCL-1000, BioWhittaker (Lonza), MD.

Lavage and serum protein analysis and histology

Total cell counts, cell differentials, and total protein, and SP-D protein analyses in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and IgE antibody analyses in the serum were performed. Briefly, lungs were lavaged with 1 ml × 3 of PBS/0.1 mM EDTA solution and collected BALF was centrifuged to pellet the cells; only the supernatant from the first ml collected was aliquoted and frozen at − 80°C for later use in cytokine, total protein, and Western blot assays. Cell viability was determined via trypan blue exclusion. Cell differentials were determined on at least 500 cells using standard hematological criteria using cytospin preps stained with Wright-Giemsa. Total protein was determined using a Micro BCA*Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using the microtiter plate protocol and a standard curve prepared from assaying known amounts of bovine serum albumin. Cytokine protein levels were analyzed via ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Serum samples were analyzed for total IgE via ELISA (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). To measure SP-D protein levels equivalent amounts of BALF supernatant (25 μl/lane) were electrophoresed and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was immunoblotted with a rabbit anti-mouse Ab directed against SP-D (diluted 1/5000 in TBS containing 1% Tween 20 and 3% non-fat dry milk) and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG Ab conjugated to HRP (diluted 1/10,000 in TBS containing 1% Tween 20 and 3% non-fat dry milk). Immunoblots were developed by chemiluminescence. To obtain tissue sections for histology, lungs were inflated and fixed with 4% formaldehyde at a pressure of 25 cm of water. Tissues were embedded in paraffin 24 h after fixation. Seven-micron sections were cut and stained with Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS)-Diastase.

Isolation of DCs and T cells for flow cytometry

DCs and T cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation as previously described (34). Briefly, the lungs were perfused to remove intravascular cells and lavaged to remove cells in the airway lumen. Only lungs that were well perfused, as judged by their degree of whiteness, were excised and utilized for further analyses. Lung tissues were minced with a razor blade and digested in HBSS with the enzymes collagenase A and DNAase I (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 1 h with shaking (200 rpm) at 37°C. Single cell suspensions were obtained by passing the digest through a 40-μm mesh filter and erythrocytes were lysed by 1-min incubation in Gey’s lysis solution (0.83% NH4Cl, 0.1% KHCO3). After lysis and centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in buffer containing HBSS with 5% FCS, 2 mM EDTA, and 100 U/ml penicillin–streptomycin. Cells from the lung digests were layered on top of a 4.0% solution of Optiprep (Axis-Shield PoC AS, Rodeloekka, Norway), placed above a 16% Optiprep solution, and centrifuged at 600 × g for 20 min at RT, without applying the brakes at the end. The low-density cells, which included DCs and T cells, were isolated from the 4–16% interface. Splenocytes and lymphocytes from the mediastinal and inguinal lymph nodes were gently teased out from the tissue and passed through a 40-μm mesh filter and the erythrocytes were then lysed. Thereafter, cells were prepared for flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed using a BD LSRII (BD Biosciences, CA) at the Duke University Human Vaccine Institute Comprehensive Core facilities. Cells were incubated first with anti-mouse CD32/CD16 (Fcγ III/II Receptor) blocking antibody and then incubated with the appropriate staining reagents in PBS and 0.2% BSA buffer for 30 min at 4°C. Stained cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. The following monoclonal antibodies purchased from either BioLegend, eBioScience or BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) were used for various labeling reactions: allophycocyanin (APC)/phycoerythrin (PE-H) anti-CD11c, FITC anti-MHC class II (IA/IE), PE-H anti-CD86, FITC/APC anti-CD3, PE-texas red anti-CD4, PE-H anti-CD25 and CD44, and APC anti-CD62L. For intracellular staining using FITC-Foxp3 (BD Pharmingen) or anti-BrdU antibodies (eBioscience), cells were washed well after surface staining, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and permeabilized with 0.3% saponin in HBSS+0.5% FBS for BrdU or Foxp3 staining. Since the anti-BrdU antibody was conjugated to biotin rather than a fluorophore, an additional intracellular staining with either streptavidin-AF633 (Molecular Probes) or Streptavidin-AF488 (BioLegend) was performed. At least 20,000 events per sample were collected on the FACS instrument. Data were analyzed using FlowJo 8 software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). Prior to cell marker examination, dead cells, aggregates, and debris were eliminated according to forward scatter height and area.

SP-A preparation

SP-A was purified from the lung lavage fluid of patients with alveolar proteinosis as described previously (35). Briefly, the lavage fluid was initially treated with butanol to extract SP-A from the lipids. The resulting pellet was then sequentially solubilized with octylglucoside and 5 mM Tris, pH 7.4. Extracted SP-A is treated with polymyxin agarose to reduce endotoxin contamination. SP-A preparations had final endotoxin concentrations of < 0.01 pg/mg SP-A as determined by the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay, according to manufacturers’ instructions [QCL-1000, BioWhittaker (Lonza), MD].

Ex vivo T cell stimulation assay

Single cell suspensions from lung digests and spleens were subject to density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Hypaque 1083 (Sigma) and residual RBCs were lysed. Purified CD4+ T cells were then obtained by negative selection using paramagnetic microbeads. CD4+ T cell purities averaged 97–99%. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were harvested from the marrow of the tibia and femur, washed, and cultured in complete RPMI 1640 supplemented 5% GM-CSF conditioned medium for 6 days. Loosely attached cells were harvested and negatively selected with biotinylated-Gr-1 Abs (BD Pharmingen) and streptavidin paramagnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). CD4+ T cells (~100,000) were incubated under different experimental conditions in Costar 96-well round-bottom plates in complete RPMI, (RPMI 1640 with 5% heat inactivated FBS (Hyclone)), 25 mM HEPES, 5 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine (all from GIBCO, Invitrogen, NY). T cell activation was performed with either 2 μg/ml Con A (Sigma) or indicated ratios of DCs pulsed with OVA. Exogenous SP-A was functionally titered to saturating levels prior to performing and was added at 20 μg/ml at the beginning of the culture. 0.8 μCi of [3H]thymidine (6.7 Ci/mmol; MP Bio) was added to each well for the final 15 h of culture. Incorporated radioactivity (as an indicator of proliferation) was measured by liquid scintillation using CytoScint ES (MP Bio) on a TriCarb 2100TR (Packard Instruments) or MiniBeta counter. IL-4 ELISAs were performed from culture supernatants using eBioScience Ready-Set-Go kits, according to manufacturer instructions.

In vivo T cell proliferation assay

To track the proliferation of T cell subsets in vivo, mice were given i.p. injections of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) at least 2 hrs before each OVA aerosol treatment and supplied water supplemented with 0.8 mg/ml BrdU in 4% sucrose ad libitum during the OVA aerosol period (Days 21–23). Single cell preparations from lung digests or spleen were labeled with T cell markers and analyzed by flow cytometry for BrdU incorporation in the nucleus (36).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS V17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) or Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc, Ca). Results are reported as group means ± SEM. Parametric data were analyzed by ANOVA to determine differences among group means and then by the Tukey’s multigroup comparison to determine which group means differed significantly. Where mentioned, pairwise comparisons using the Mann-Whitney test were performed. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

SP-A−/− mice exhibit enhanced Th2-associated responses during allergen-mediated lung inflammation

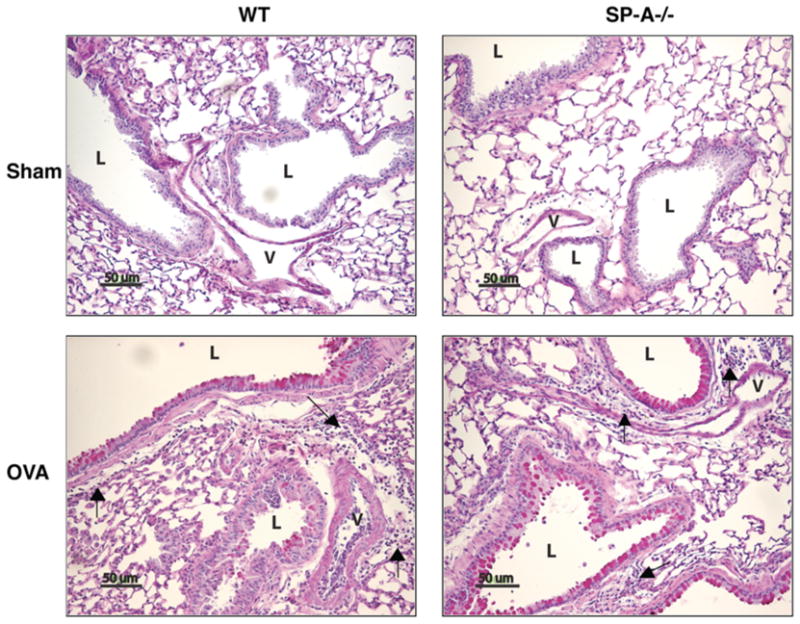

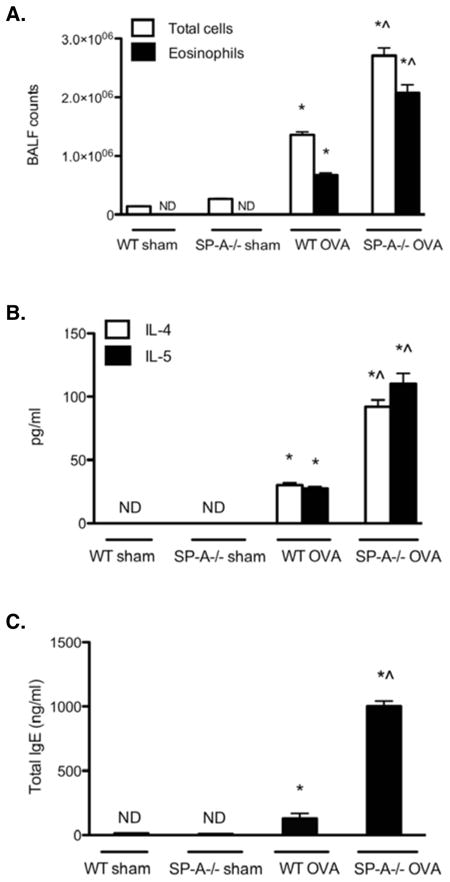

Hallmark indicators of allergic asthma include airway eosinophilia and the production of mucin, Th2-patterned cytokines, and IgE antibodies (37). To assess the influence of SP-A on these parameters, SP-A−/− and WT mice were sensitized and challenged with OVA (SP-A−/− OVA, WT OVA) and the lungs were lavaged, excised, and prepared for analysis. Normal lung histology was observed in the absence of OVA exposure (Fig. 1, WT sham and SP-A−/− sham). Both WT and SP-A−/− OVA mice exhibited the expected OVA-mediated histological changes as demonstrated by perivascular and peribronchiolar inflammatory cell infiltration and mucin production (Fig. 1). The SP-A−/− OVA mice exhibited increased total cell and eosinophil counts (Fig. 2A) in the BALF compared with their WT counterparts. SP-A−/− OVA mice had greater BALF IL-4 and IL-5 protein levels (Fig. 2B) and serum IgE levels (Fig. 2C) compared to WT OVA mice, suggesting that SP-A modulates the extent of the Th2 response and subsequent humoral response in allergen-mediated lung inflammation. The levels of Th1-associated cytokines, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-12 in the BALF did not differ between the OVA groups (data not shown), suggesting that SP-A preferentially downregulated the Th2-associated response. The levels of total protein, as a measure of epithelial layer integrity, have been reported to increase in the BALF of OVA challenged mice (38, 39). The differences in the levels of inflammation between the WT and SP-A−/− OVA mice as measured by BALF cell counts and cytokine levels do not appear to be a consequence of variations in total protein levels (data not shown) nor in SP-D levels (data not shown) because these measures increased similarly in the BALF of both OVA groups.

Figure 1. Inflammatory cellular infiltrates and mucus production in the lung tissue of OVA mice.

Histology was evaluated 24 h after the last aerosol exposure in PAS-Diastase stained tissue sections (bar = 50μm). Mucus is stained bright pink. L, airway lumen; V, blood vessel lumen; →, mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate. Representative of 2 mice/group from 3 separate experiments.

Figure 2. SP-A−/− OVA mice have elevated Th2-associated inflammatory indices.

BALF cells were counted and cell differentials were determined using standard hematological criteria. Eosinophil counts were derived by multiplying the percent of eosinophils by the total BALF cell counts. (n = 10 mice/group; *, p < 0.05 as compared to sham-treated controls, which did not differ from each other; ^, p < 0.05 as compared to WT OVA). BALF supernatant was collected and analyzed for (A) IL-4 and IL-5 protein by ELISA. Results are reported as picograms per ml (pg/ml) of BALF supernatant (n = 8–10 mice/group; *, p < 0.05 as compared to sham-treated controls, whose levels were not detectable (ND); ^, p < 0.05 as compared to WT OVA). Serum samples were monitored for changes in total IgE levels via ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. Results for total IgE levels are reported as nanograms per ml (ng/ml) of serum. (n = 10; *, p < 0.05 as compared with sham-treated controls, whose levels were ND; ^, p < 0.05 as compared with WT OVA).

SP-A−/− and WT mice have similar proportions of mature DCs and Foxp3 expressing CD4+/CD25+ TREG cells in the lungs during allergen-mediated lung inflammation

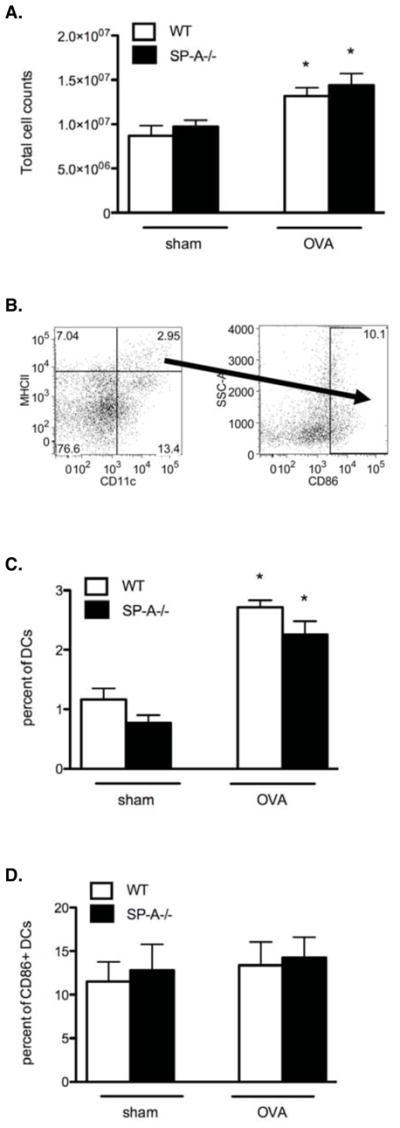

To determine whether SP-A in the lung microenvironment influences DC phenotype, we analyzed DCs for the expression of MHCII and costimulatory molecules, which are essential for the initiation and amplification of T cell-mediated responses and serve as an index of DC functional maturity (40). CD86 is the predominant costimulatory ligand on DCs responsible for CD28 mediated costimulation that leads to T cell activation (41). In flow cytometric assays DCs were discriminated from alveolar macrophages by taking advantage of the high autofluorescence of alveolar macrophages and the variation in the levels of MHC class II expression (42–45). Thus, we identified DCs as CD11c+ and MHCIIhi cell surface staining. As expected, the total numbers of low-density cells and the percent of DCs within that pool of cells increased in response to OVA challenge (Fig. 3, A and C) and the total number of DCs and CD86+ DCs in the lungs increases comparably between WT and SP-A−/− OVA mice in response to OVA challenge (data not shown). In addition, the geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MHCII and CD86 surface expression did not differ among the groups of mice (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicated that SP-A does not specifically alter the phenotype and prevalence of DCs, including those expressing the maturation marker CD86, in response to allergen challenge.

Figure 3. WT and SP-A−/− OVA mice have similar proportions of low-density cells and DCs in the lungs.

A, Representative profile of total lung digest cell counts after density gradient centrifugation (3–4 lungs pooled/group). B, Representative gating strategy shown in SP-A−/− OVA mice to determine the percent of DCs, identified by CD11c+ and MHCIIhi cell surface staining, and percent of DCs that stain CD86+ (CD86+ DCs) using flow plots. C, The percent of cells expressing CD11c+/MHCIIhi as determined by the strategy described in (B). D, The percent of cells expressing CD86 as determined by the strategy described in (B). (n = 4 independent experiments, 2 mouse samples/group/experiment; *, p < 0.05 as compared to sham-treated controls, which did not differ from each other).

CD25, the high affinity IL-2 receptor alpha chain, contributes to T cell activation by stimulating proliferative pathways in response to autocrine and paracrine IL-2. CD25 is expressed in the global T cell population upon activation. It is also expressed constitutively on Foxp3+ TREG cells, which inhibit DCs from initiating Th2-driven responses and suppress Th2 effector cell function (28–30). Thus, we determined whether the presence of SP-A in the lung microenvironment influences the proportions of CD25+ and Foxp3+/CD25+ T cells in the lung. Although flow cytometric data revealed that the total numbers of CD3+/CD4+ cells in the lungs were not statistically different among the groups, the percent of CD3+/CD4+ T cells that expressed CD25 tended to be highest in the SP-A−/− OVA group (data not shown). However, there was no difference in the percent of CD25 cells that concurrently expressed Foxp3 among the groups (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that although SP-A does not modify the prevalence of Foxp3 expressing CD4+/CD25+ TREG cells in lungs in response to allergen challenge, it nominally alters the prevalence of CD4+ T cells that express the activation marker CD25. This phenotypic state was further corroborated by functional studies using the pan-T cell mitogen, Con A. As seen in Supplementary Figure 1, the level of proliferation remains inherently higher in the SP-A−/− OVA group. These results directly led us to explore whether the lungs of SP-A−/− mice had a greater proportion of activated or effector T cells.

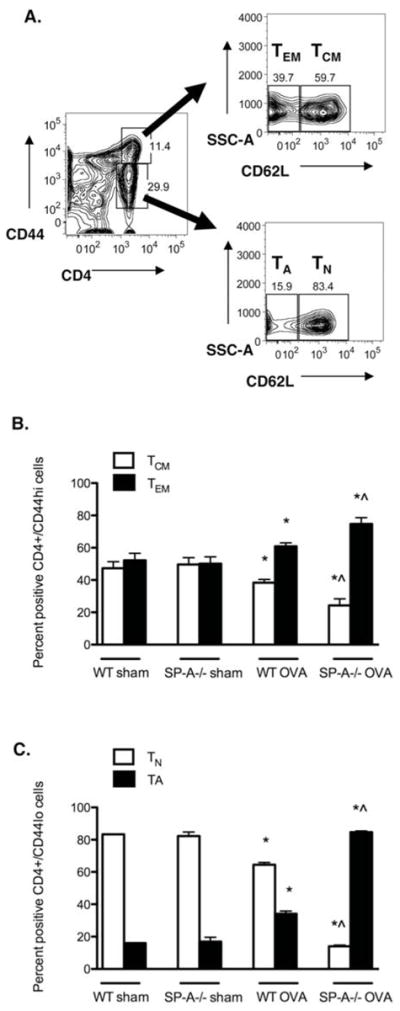

A greater proportion of pre-activated and effector memory CD4+ T cells are present in the lungs of SP-A−/− mice during allergen-mediated lung inflammation

Th2-associated cytokine levels and IgE levels were increased in the SP-A−/− OVA mice, suggesting that SP-A either directly or indirectly modulates CD4+ phenotype and Th2 functions. Because SP-A did not alter the phenotype or prevalence of DCs and TREG cells, we predicted instead that SP-A influences the immunomodulatory repertoire of CD4+ T cells, especially with respect to naive and memory/effector cells, which could account for the differences in inflammatory indices found between the OVA groups.

As described above, the total numbers of CD3+/CD4+ cells in the lungs did not differ among the groups. However, of the CD3+/CD4+/CD44hi population, the percent of TCM cells (CD62L+) and percent TEM cells (CD62Lneg) was 24% and 75%, respectively, in the SP-A−/− OVA mice compared to 38% and 61%, respectively, in the WT OVA mice and to 50% in both sham mouse groups (Fig. 4B). Of the CD3+/CD4+/CD44low population, the percent of TN cells (CD62L+) and percent of TA cells (CD62Lneg) was 14% and 85%, respectively, in the SP-A−/− OVA mice. These proportions were dramatically altered in the WT OVA to 65% and 34%, respectively. Baseline levels in both sham groups were 83% and 17%, respectively (Fig. 4C). To assess whether the effect of SP-A on altering the ratios of T cell subsets was restricted to the lung, T cell subsets in the mediastinal lymph nodes, inguinal lymph nodes, and the spleen were also analyzed. No differences were noted among the groups in the peripheral tissues (Supplementary Figure 2), indicating that the effects of SP-A on T cell phenotype were localized to the cells found specifically within the lung.

Figure 4. SP-A−/− OVA mice have the greatest proportion of TA and TEM cells in the lungs.

A, Representative gating strategy used to determine the percentages of previously activated (TA) and naïve (TN) cells and of effector memory (TEM) and central memory (TCM) T cells in the lungs. Percent of CD3+/CD4+/CD44low T cells that express CD62Lneg staining correspond to TA cells and the percent of CD3+/CD4+/CD44low T cells that express CD62L+ staining correspond to TN cells. Percent of CD3+/CD4+/CD44hi T cells that express CD62Lneg staining correspond to TEM cells and the percent of CD3+/CD4+/CD44+ T cells that express CD62L+ staining correspond to TCM cells. B, Percent of TA and naïve TN cells. C, Percent TEM and TCM cells. (n = 4 independent experiments, 2 mouse samples/group/experiment; p < 0.05; *, as compared to sham-treated controls, which did not differ from each other, ^ as compared to WT OVA).

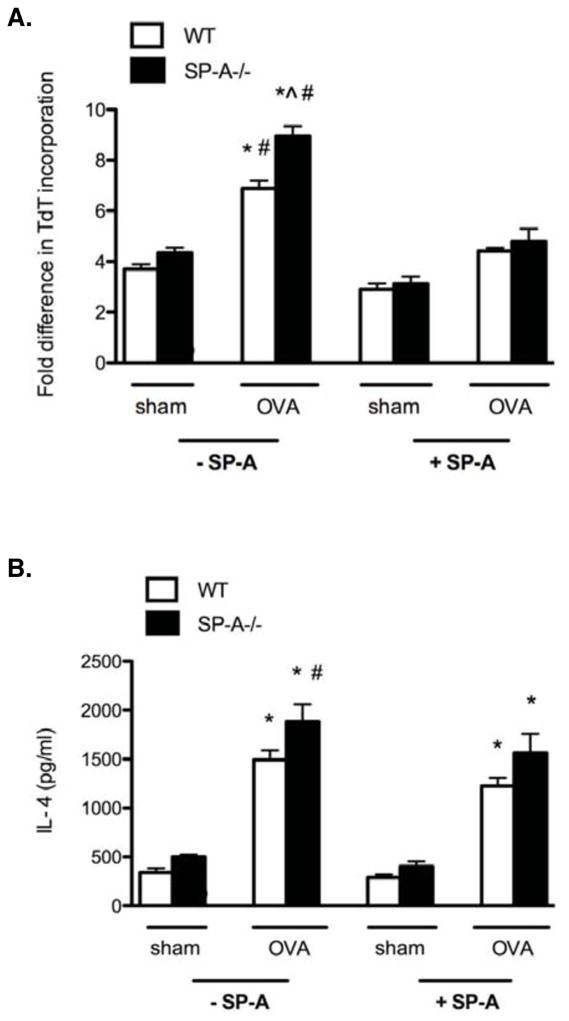

The CD4+ T cells from the lungs of SP-A−/− OVA mice are hyperresponsive to ex vivo recall stimulation and this capacity is attenuated with exogenous SP-A treatment

To determine if the alterations in CD4+ T cell phenotypic ratios described above translated into changes in effector function, we isolated CD4+ T cells from the spleens and lungs of each respective mouse group and stimulated the total CD4+ T cell population with varying ratios of OVA-primed BMDCs and OVA ex vivo. Cellular proliferation was assayed by [3H]-thymidine incorporation recorded as mean cpm and representative data are reported as fold differences compared to unstimulated control (T cells + unprimed BMDCs) (Fig. 5A). Lung derived T cells from the SP-A−/− OVA mice had the greatest proliferative capacity compared to all other groups; SP-A−/− OVA cells had approximately a 2 fold enhancement in proliferation compared to the cells from the sham mice and ~30% enhanced proliferation compared to cells from the WT OVA mice. Supernatant levels of IL-4 were also greatest in the SP-A−/− OVA T cell samples (Fig. 5B). Addition of 20 μg/ml of exogenous SP-A in cell culture reduced proliferation by ~40% in the cells from OVA-exposed mice compared to those from the sham mice. Surprisingly, IL-4 secretion was not as dramatically affected, suggesting that SP-A is able to reduce proliferation without affecting Th2 cytokine production. These results, combined with the Th2-inflammatory response data (Fig. 1), indicate that the global CD4+ T cell population from the SP-A deficient lungs is hyperresponsive during OVA-stimulatory conditions and provide corroborating evidence that a shift in CD4+ T cell profile toward that of an effector phenotype has occurred.

Figure 5. CD4+ T cells from SP-A−/− OVA mice are hyperresponsive to ex vivo recall stimulation and this capacity is attenuated with exogenous SP-A treatment.

Primary mouse lung-derived T cells were purified and activated ex vivo with 40 μg/ml of OVA and 1:10 ratio of BMDC: T cells. Where indicated cells were treated with exogenous SP-A (20 μg/ml). A, Activation was performed for 50 h with a [3H]-thymidine pulse during the last 15 h. Data is represented as fold difference in cellular proliferation normalized to the unstimulated WT cells condition. B, IL-4 was measured from the respective culture supernatants at 30 h post activation. (n = 3 – 4 independent experiments, 2 mouse samples/group/experiment; Mann-Whitney pairwise comparison, p < 0.05; *, as compared to sham-treated controls that were either treated or not treated with exogenous SP-A, which did not differ from each other; ^ as compared to WT OVA not treated with exogenous SP-A, # as compared to OVA groups treated with exogenous SP-A.

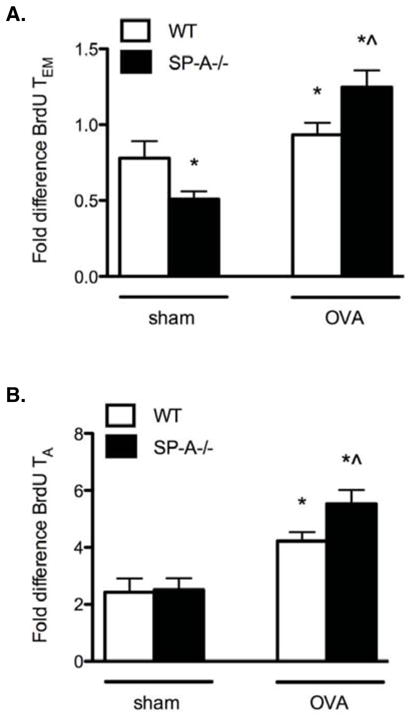

Activated and effector memory CD4+ T cells proliferate to a greater extent in the lungs of SP-A−/− mice during allergen-mediated lung inflammation

Finally, to investigate the mechanism for the increased prevalence of TA and TEM cells in the SPA-deficient condition, BrdU incorporation was analyzed in the sub-populations of lung CD4+ T cells in vivo. Data were normalized to the levels of BrdU incorporation in the control group, which was comprised of splenocytes from saline-treated WT mice. Results show that TEM and TA cells from SP-A−/− OVA mice have a higher proliferation rate compared to WT OVA mice (Fig. 6, A and B). Interestingly, TEM cells from sham treated SP-A−/− mice had reduced levels of BrdU incorporation compared to cells from sham treated WT mice. The largest fold change in both percentage and numbers was observed in the TA cells, which are the pre-dominant responder population and which have the potential to convert to memory cells under conditions of OVA-stimulation. Thus, lung effector memory and activated CD4+ T cells display enhanced proliferation in SP-A−/− mice during allergen-mediated inflammation.

Figure 6. TEM and TA cells proliferate to the greatest extent in the lungs of SP-A−/− OVA mice.

Mice were given intraperitoneal injections of BrdU before each OVA aerosol treatment and the drinking water was supplemented with BrdU during the OVA aerosol period. Single cell preparations from lung digests or spleen were labeled with T cell phenotypic markers (CD3, CD4, CD44, CD62L) and simultaneously analyzed by flow cytometry for BrdU incorporation in the nucleus. Data are represented as mean fold difference normalized to the sham-treated WT CD4+ splenic T cell population. A, Fold differences in BrdU+ TEM cells. (n = 3 independent experiments, 3 mouse samples/group/experiment; Mann-Whitney pairwise comparison, p < 0.05; *, as compared to WT sham, ^ as compared to WT OVA). B, Fold differences in BrdU+ TA cells. (n = 3 independent experiments, 3 mouse samples/group/experiment; Mann-Whitney pairwise comparison, p < 0.05; *, as compared to sham-treated controls, which did not differ from each other, ^ as compared to WT OVA).

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to investigate the phenotype and prevalence of lung-derived adaptive immune cells during allergen-induced inflammation in a SP-A-deficient condition. We demonstrate that TA and TEM cells from OVA-exposed SP-A deficient mice exhibited the greatest extent of in vivo proliferation, correlating with striking phenotypic data showing that these mice had the greatest proportions of CD4+ TA and TEM cells and the lowest proportions of TN and TCM cells in their lungs. This phenotypic shift correlated with an increased proliferative and IL-4-producing capacity ex vivo and with a greater extent of eosinophilia and IL-4 and IL-5 cytokine levels in the BALF and IgE levels in the serum. Taken together, we have identified an important role for SP-A in inhibiting the proliferation of CD4+ TA and TEM subpopulations and inhibiting Th-2-associated inflammatory indices.

SP-A levels have been reported to either increase or decrease (14, 46, 47) in allergic hypersensitivity conditions. For instance, Haley et al. (48), who used a shorter priming but longer and more concentrated OVA aerosol protocol than we did, found increased expression of SP-A in lavage fluid and in nonciliated epithelial cells of noncartilaginous airways. However, a specific decrease in SP-A levels during allergic inflammation was observed in mouse studies that used either Aspergillus fumigatus (Afu), a ubiquitous airborne saprophytic fungi, or dust mite allergen (11, 49). A recently published, well-controlled human study by Erpenbeck et al. (14) showed that segmental allergen challenge in subjects with asthma resulted in massive eosinophil influx with specific increases in SP-B, SP-C, and SP-D and a decrease in SP-A BALF levels. Importantly, in this study, SP levels were compared with baseline and saline control challenge in the same subjects. These alterations occurred in the absence of a concomitant change in total phospholipid levels in the cell-free BALF, suggesting that SP levels are regulated independently from surfactant phospholipid synthesis and secretion. Increasing evidence also shows that polymorphisms in the SP-A genes (SP-A1 and SP-A2) affect the protein expression of functional SP-A (reviewed in (50)). Our study provides further evidence that surfactant protein deficiency or inactivation has the potential to modify the severity of inflammation in allergic lung diseases like asthma.

Under steady-state conditions, lung DCs undergo slow but constitutive migration to draining lymph nodes and can remain there for several days to confer antigen-specific tolerance. In response to allergen exposure in asthma, the numbers of DCs increase (51), particularly in the lower airways as a result of recruited myeloid precursors (52), and then migrate with an increased rate and magnitude to the lymph nodes (53, 54). The concept that SP-A can affect the phenotype and chemotactic responses of DCs was shown in a previous in vitro study conducted in our lab by Brinker et al. (16). Incubation with SP-A decreased the numbers of BMDCs that migrated toward the secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine/CCL21-induced chemokine gradient (16) and decreased the extent of DC maturation. In contrast, we did not find an increase in the prevalence of matured DCs in the absence of SP-A either in the sham or the OVA condition. Brinker et al. used a relatively short-term acute LPS exposure to stimulate the maturation of the BMDCs. Thus, the lack of differences in MHCII and CD86 MFI in our current study may be a consequence of the different agonists used (LPS versus OVA) or the time of analysis. Another possibility is that the previous study was conducted using BMDCs, which may respond differently to surfactant proteins than lung-derived DCs (34, 55, 56). In addition, we examined the later phase of the secondary challenge (i.e., after the third day of OVA aerosol challenge), but it is possible that SP-A interacts differentially with DCs to alter the maturation and trafficking processes at the early phases of the secondary challenge.

Gaining increasing attention is the notion that DCs may not actually be a separate cell type with unique functions but rather part of the mononuclear phagocyte system since they are derived from a common precursor, responsive to the same growth factors (including CSF-1), express the same surface markers (including CD11c), and have no unique adaptation for Ag presentation that is not shared by other macrophages (57). Guth et al. recently demonstrated that the airway environment with locally high concentrations of GM-CSF and, to a lesser extent, SP-D, promotes the development of macrophages with unique DC-like characteristics, illustrating that the phenotype was not predetermined but was, instead, a product of the environment (58). Thus, the distinction between macrophages and DCs are not always clear, particularly in the lung.

Previously published data from our lab and others show that T cells from the alveolar airspace are functionally different than T cells from the circulation and that both surfactant lipids and proteins alter T cell functions in vitro (17, 59–62). The results presented in this current study clearly show that T cells isolated from lung digests of SP-A−/− mice challenged with OVA differ from those isolated from the WT mice challenged with OVA. Therefore, SP-A must be acting on T cells locally in the airspace, making its way from the airspace to the parenchyma to affect T cells there, or acting indirectly by mediating the functions of antigen presenting or other cells that in turn modulate T cells. Determining whether SP-A can act directly on T cells while they are in the airspace or parenchyma and/or whether SP-A is influencing the activity of other cells that in turn modulate T cells in these different locations are important questions to be addressed in future studies.

The proliferative capacity of T cells from the lungs of the SP-A−/− OVA mice was greater in ex vivo assays using Con A or OVA recall stimulation compared to T cells from the WT OVA mice. However, the proliferative capacity of T cells from the WT and SP-A−/− sham mice did not differ and addition of exogenous SP-A to cultures of either WT OVA or SP-A−/− OVA T cells resulted in inhibition of OVA-induced proliferation, both of which suggest that that there are no differences in intrinsic proliferative capacity or responsiveness to SP-A between T cells from WT and SP-A−/− T mice. We hypothesize that the higher proliferative capacity in the SP-A−/− OVA cells can be attributed to the larger proportion of T cells that are primed to respond to stimuli in the these mice, i.e., larger proportion of CD25-expressing cells and TA cells in the case of the Con A assays and larger proportion of TEM cells in case of the OVA recall assays.

The presence or absence of proinflammatory subsets of T cells has major effects on the course and outcome of inflammatory reactions in the lungs secondary to the distinct cytokines secreted (63–67). Th2 TEM cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of asthma because they are known to accumulate in the lung and produce cytokines rapidly. Although it is debatable as to whether there is a true shift toward a Th2 bias or whether there is a concomitant diminishment of Th1 activity, increased levels of Th2 cell-secreted IL-4 and IL-5 have been repeatedly observed in the BALF of subjects with asthma (32). The increased Th2 cytokine profile, IgE production, and eosinophilia as well as hyperresponsivity of the isolated CD4+ T cells we observed are consistent with a predominant prevalence of an effector CD4+ T cell phenotype in the SP-A-deficient condition.

Based on our findings, we propose the following model. The presence of adequate amounts of functional SP-A in the lung milieu negatively regulates the prevalence of effector memory CD4+ T cells in the lung tissues during allergen-induced inflammation. Because of a decreased pool of effector memory CD4+ T cells, there is a concomitant decrease in the production of Th2-associated cytokines, which in turn affects the recruitment or survival of eosinophils and diminishes the IgE-mediated humoral response. Thus, the overall effect of the presence of SP-A in the lung is a reduction in several inflammatory indices associated with allergen-mediated lung inflammation. Understanding the mechanisms by which SP-A influences the phenotype and homing specificity of cells important in asthma pathogenesis could provide new targets for immunotherapy, perhaps unique SP-A-based therapies, for chronic inflammatory lung diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. William M. Foster and Ms. Erin Potts for assistance with the OVA exposures and Dr. Julia K. Walker for her critical review of the manuscript. The authors also wish to thank Dr. John F. Whitesides and Ms. Patrice McDermott in the Duke Human Vaccine Institute Research Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Facility for assistance with flow cytometry procedures.

This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI grants 5P50HL084917 and 5R01HL68072. A.M.P. was supported by NIH/NIAID 1K08AI068822 and additionally by Duke University’s Center for Comparative Biology of Vulnerable Populations 5P30-ES-011961-04. G.D.S. is supported by AG25150. The Duke Human Vaccine Institute Flow Cytometry Core Facility is supported by NIH AI-051445.

Non-standard abbreviations

- SP-A

surfactant protein A

- SP-A−/−

SP-A deficient

- DC

dendritic cell

- WT

wild-type

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- BMDCs

bone marrow-derived DCs

References

- 1.Crouch EC. Collectins and Pulmonary Host Defense. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:177–201. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid KBM. Functional Roles of the Lung Surfactant Proteins SP-A and SP-D in Innate Immunity. Immunobiology. 1998;199:200–207. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright JR. Immunomodulatory functions of surfactant. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:931–962. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crouch EC. Modulation of host-bacterial interactions by collectins. American Journal of Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology. 1999;21:558–561. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.5.f169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawson PR, Reid KB. The roles of surfactant proteins A and D in innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:66–78. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeVine AM, Bruno MD, Huelsman KM, Ross GF, Whitsett JA, Korfhagen TR. Surfactant protein-A deficient mice are susceptible to group B streptococcal infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:4336–4340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeVine AM, Kurak KE, Bruno MD, Stark JM, Whitsett JA, Korfhagen TR. Surfactant protein-A-deficient mice are susceptible to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:700–708. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.4.3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeVine AM, Kurak KE, Wright JR, Watford WT, Bruno MD, Ross GF, Whitsett JA, Korfhagen TR. Surfactant protein-A binds group B Streptococcus enhancing phagocytosis and clearance from lungs of surfactant protein-A-deficient mice. American Journal of Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology. 1999;20:279–286. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.2.3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeVine AM, Gwozdz J, Stark J, Bruno M, Whitsett J, Korfhagen T. Surfactant protein-A enhances respiratory syncytial virus clearance in vivo. Journal Of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103:1015–1021. doi: 10.1172/JCI5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Gwynn C, Redd SC. Surveillance for asthma--United States, 1980–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atochina EN, Beers MF, Tomer Y, Scanlon ST, Russo SJ, Panettieri RA, Jr, Haczku A. Attenuated allergic airway hyperresponsiveness in C57BL/6 mice is associated with enhanced surfactant protein (SP)-D production following allergic sensitization. Respir Res. 2003;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scanlon ST, Milovanova T, Kierstein S, Cao Y, Atochina EN, Tomer Y, Russo SJ, Beers MF, Haczku A. Surfactant protein-A inhibits Aspergillus fumigatus-induced allergic T-cell responses. Respir Res. 2005;6:97. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Graaf EA, Jansen HM, Lutter R, Alberts C, Kobesen J, de Vries IJ, Out TA. Surfactant protein A in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:252–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erpenbeck VJ, Schmidt R, Gunther A, Krug N, Hohlfeld JM. Surfactant protein levels in bronchoalveolar lavage after segmental allergen challenge in patients with asthma. Allergy. 2006;61:598–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deb R, Shakib F, Reid K, Clark H. Major house dust mite allergens Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus 1 and Dermatophagoides farinae 1 degrade and inactivate lung surfactant proteins A and D. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36808–36819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinker KG, Garner H, Wright JR. Surfactant protein A modulates the differentiation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L232–241. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00187.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borron PJ, Mostaghel EA, Doyle C, Walsh ES, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Wright JR. Pulmonary surfactant proteins A and D directly suppress CD3+/CD4+ cell function: evidence for two shared mechanisms. J Immunol. 2002;169:5844–5850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JY, Shieh CC, You PF, Lei HY, Reid KB. Inhibitory effect of pulmonary surfactant proteins A and D on allergen-induced lymphocyte proliferation and histamine release in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:510–518. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9709111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madan T, Kishore U, Singh M, Strong P, Clark H, Hussain EM, Reid KB, Sarma PU. Surfactant proteins A and D protect mice against pulmonary hypersensitivity induced by Aspergillus fumigatus antigens and allergens. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:467–475. doi: 10.1172/JCI10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akbari O, Freeman GJ, Meyer EH, Greenfield EA, Chang TT, Sharpe AH, Berry G, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Antigen-specific regulatory T cells develop via the ICOS-ICOS-ligand pathway and inhibit allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2002;8:1024–1032. doi: 10.1038/nm745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akbari O, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Pulmonary dendritic cells producing IL-10 mediate tolerance induced by respiratory exposure to antigen. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:725–731. doi: 10.1038/90667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christman JW, Sadikot RT, Blackwell TS. The role of nuclear factor-kappa B in pulmonary diseases. Chest. 2000;117:1482–1487. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whelan M, Harnett MM, Houston KM, Patel V, Harnett W, Rigley KP. A filarial nematode-secreted product signals dendritic cells to acquire a phenotype that drives development of Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:6453–6460. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell JJ, Brightling CE, Symon FA, Qin S, Murphy KE, Hodge M, Andrew DP, Wu L, Butcher EC, Wardlaw AJ. Expression of chemokine receptors by lung T cells from normal and asthmatic subjects. J Immunol. 2001;166:2842–2848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parameswaran N, Suresh R, Bal V, Rath S, George A. Lack of ICAM-1 on APCs during T cell priming leads to poor generation of central memory cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:2201–2211. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iezzi G, Scheidegger D, Lanzavecchia A. Migration and function of antigen-primed nonpolarized T lymphocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 2001;193:987–993. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Exploring pathways for memory T cell generation. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:805–806. doi: 10.1172/JCI14005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewkowich IP, Herman NS, Schleifer KW, Dance MP, Chen BL, Dienger KM, Sproles AA, Shah JS, Kohl J, Belkaid Y, Wills-Karp M. CD4+CD25+ T cells protect against experimentally induced asthma and alter pulmonary dendritic cell phenotype and function. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1549–1561. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadeiba H, Locksley RM. Lung CD25 CD4 regulatory T cells suppress type 2 immune responses but not bronchial hyperreactivity. J Immunol. 2003;170:5502–5510. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ling EM, Smith T, Nguyen XD, Pridgeon C, Dallman M, Arbery J, Carr VA, Robinson DS. Relation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell suppression of allergen-driven T-cell activation to atopic status and expression of allergic disease. Lancet. 2004;363:608–615. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15592-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson DS, Larche M, Durham SR. Tregs and allergic disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1389–1397. doi: 10.1172/JCI23595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wills-Karp M. Immunologic basis of antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bentley AM, Menz G, Storz C, Robinson DS, Bradley B, Jeffery PK, Durham SR, Kay AB. Identification of T lymphocytes, macrophages, and activated eosinophils in the bronchial mucosa in intrinsic asthma. Relationship to symptoms and bronchial responsiveness. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:500–506. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.2.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen S, Lo B, Evans K, Neophytou P, Holmskov U, Wright JR. Surfactant protein D augments bacterial association but attenuates major histocompatibility complex class II presentation of bacterial antigens. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:94–102. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0195OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McIntosh JC, Mervin-Blake S, Conner E, Wright JR. Surfactant Protein A protects growing cells and reduces TNF-Alpha activity from LPS-stimulated macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1996;15:L 310–L 319. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.2.L310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tough DF, Sprent J, Stephens GL. Measurement of T and B cell turnover with bromodeoxyuridine. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2007;Chapter 4(Unit 4):7. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0407s77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laitinen LA, Laitinen A. Remodeling of asthmatic airways by glucocorticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)80215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeda K, Miyahara N, Rha YH, Taube C, Yang ES, Joetham A, Kodama T, Balhorn AM, Dakhama A, Duez C, Evans AJ, Voelker DR, Gelfand EW. Surfactant Protein D Regulates Airway Function and Allergic Inflammation through Modulation of Macrophage Function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:783–789. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-548OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haczku A, Cao Y, Vass G, Kierstein S, Nath P, Atochina-Vasserman EN, Scanlon ST, Li L, Griswold DE, Chung KF, Poulain FR, Hawgood S, Beers MF, Crouch EC. IL-4 and IL-13 form a negative feedback circuit with surfactant protein-D in the allergic airway response. J Immunol. 2006;176:3557–3565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staeva-Vieira TP, Freedman LP. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits IFN-gamma and IL-4 levels during in vitro polarization of primary murine CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:1181–1189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inaba K, Witmer-Pack M, Inaba M, Hathcock KS, Sakuta H, Azuma M, Yagita H, Okumura K, Linsley PS, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Hodes RJ, Steinman RM. The tissue distribution of the B7-2 costimulator in mice: abundant expression on dendritic cells in situ and during maturation in vitro. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1849–1860. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirby AC, Raynes JG, Kaye PM. CD11b regulates recruitment of alveolar macrophages but not pulmonary dendritic cells after pneumococcal challenge. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:205–213. doi: 10.1086/498874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Demedts IK, Brusselle GG, Vermaelen KY, Pauwels RA. Identification and characterization of human pulmonary dendritic cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:177–184. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0279OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vermaelen K, Pauwels R. Accurate and simple discrimination of mouse pulmonary dendritic cell and macrophage populations by flow cytometry: methodology and new insights. Cytometry A. 2004;61:170–177. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Rijt LS, Kuipers H, Vos N, Hijdra D, Hoogsteden HC, Lambrecht BN. A rapid flow cytometric method for determining the cellular composition of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cells in mouse models of asthma. J Immunol Methods. 2004;288:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright SM, Hockey PM, Enhorning G, Strong P, Reid KB, Holgate ST, Djukanovic R, Postle AD. Altered airway surfactant phospholipid composition and reduced lung function in asthma. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1283–1292. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng G, Ueda T, Numao T, Kuroki Y, Nakajima H, Fukushima Y, Motojima S, Fukuda T. Increased levels of surfactant protein A and D in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids in patients with bronchial asthma. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:831–835. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.16583100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haley KJ, Ciota A, Contreras JP, Boothby MR, Perkins DL, Finn PW. Alterations in lung collectins in an adaptive allergic immune response. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L573–584. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00117.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang JY, Shieh CC, Yu CK, Lei HY. Allergen-induced bronchial inflammation is associated with decreased levels of surfactant proteins A and D in a murine model of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:652–662. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pastva AM, Wright JR, Williams KL. Immunomodulatory roles of surfactant proteins A and D: implications in lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:252–257. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-018AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Havenith CE, Breedijk AJ, Hoefsmit EC. Effect of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin inoculation on numbers of dendritic cells in bronchoalveolar lavages of rats. Immunobiology. 1992;184:336–347. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jahnsen FL, Moloney ED, Hogan T, Upham JW, Burke CM, Holt PG. Rapid dendritic cell recruitment to the bronchial mucosa of patients with atopic asthma in response to local allergen challenge. Thorax. 2001;56:823–826. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.11.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamath AT, Henri S, Battye F, Tough DF, Shortman K. Developmental kinetics and lifespan of dendritic cells in mouse lymphoid organs. Blood. 2002;100:1734–1741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruedl C, Koebel P, Bachmann M, Hess M, Karjalainen K. Anatomical origin of dendritic cells determines their life span in peripheral lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2000;165:4910–4916. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez-Juarrero M, I, Orme M. Characterization of murine lung dendritic cells infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1127–1133. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1127-1133.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nicod LP, Cochand L, Dreher D. Antigen presentation in the lung: dendritic cells and macrophages. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:246–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hume DA. Macrophages as APC and the dendritic cell myth. J Immunol. 2008;181:5829–5835. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guth AM, Janssen WJ, Bosio CM, Crouch EC, Henson PM, Dow SW. Lung environment determines unique phenotype of alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L936–946. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90625.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaltreider HB, Salmon SE. Immunology of the lower respiratory tract. Functional properties of bronchoalveolar lymphocytes obtained from the normal canine lung. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:2211–2217. doi: 10.1172/JCI107406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ansfield MJ, Kaltreider HB, Benson BJ, Shalaby MR. Canine surface active material and pulmonary lymphocyte function. Studies with mixed-lymphocyte culture. Exp Lung Res. 1980;1:3–11. doi: 10.3109/01902148009057508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borron P, McCormack FX, Elhalwagi BM, Chroneos ZC, Lewis JF, Zhu S, Wright JR, Shepherd VL, Possmayer F, Inchley K, Fraher LJ. Surfactant Protein A Inhibits T Cell Proliferation Via Its Collagen-Like Tail and a 210-Kda Receptor. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular & Molecular Physiology. 1998;19:L 679–L 686. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.4.L679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borron P, Veldhuizen RA, Lewis JF, Possmayer F, Caveney A, Inchley K, McFadden RG, Fraher LJ. Surfactant associated protein-A inhibits human lymphocyte proliferation and IL-2 production. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:115–121. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.1.8679215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hamann A, Syrbe U. T-cell trafficking into sites of inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:696–699. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.7.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bromley SK, Thomas SY, Luster AD. Chemokine receptor CCR7 guides T cell exit from peripheral tissues and entry into afferent lymphatics. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:895–901. doi: 10.1038/ni1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tager AM, Bromley SK, Medoff BD, Islam SA, Bercury SD, Friedrich EB, Carafone AD, Gerszten RE, Luster AD. Leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 mediates early effector T cell recruitment. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:982–990. doi: 10.1038/ni970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goodarzi K, Goodarzi M, Tager AM, Luster AD, von Andrian UH. Leukotriene B4 and BLT1 control cytotoxic effector T cell recruitment to inflamed tissues. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:965–973. doi: 10.1038/ni972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luster AD, Tager AM. T-cell trafficking in asthma: lipid mediators grease the way. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:711–724. doi: 10.1038/nri1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.