Abstract

Background

The association between Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) Ala222Val (rs1801133) has been implicated to alter the risk of bladder cancer, but the results are controversial.

Methods

A comprehensive databases of Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM) were searched for case–control studies investigating the association between MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and bladder cancer susceptibility. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were used to assess this possible association. A χ2-based Q-test was used to examine the heterogeneity assumption. Begg’s and Egger’s test were used to examine the potential publication bias. The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether our assumptions or decisions have a major effect on the results of the review. Statistical analysis was performed with the software program Stata 12.0.

Results

A total of 15 independent studies were identified, including 3,570 cases and 3,926 controls. Our analysis suggested that Ala222Val was not associated with bladder cancer risk in overall population under additive model (OR=0.96, 95%CI=0.76-1.21, P=0.731), dominant model (OR=1.00, 95%CI=0.87-1.15, P=0.975), recessive model (OR=0.92, 95%CI=0.79-1.07, P=0.279), and Ala allele versus Val allele (OR=0.96, 95%CI=0.86-1.07, P=0.427). In the subgroup analysis stratified by ethnicity and sources of controls, there were also no significant associations detected among different descent populations, population-based studies and hospital-based studies.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed the evidence that MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism was not contributed to the development of bladder cancer.

Virtual slide

The virtual slide(s) for this article can be found here: http://www.diagnosticpathology.diagnomx.eu/vs/2117182849994994.

Keywords: Polymorphism, Bladder cancer, MTFHR, Ala222Val, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the second most common genitourinary malignant disease, with an expected 73,510 newly diagnosed cases and 14,880 deaths in 2012 in America [1]. Many studies have suggested that several environmental factors such as cigarette smoking, aromatic amines contained in dyes, chronic inflammation due to infection, anticancer drugs and radiation are thought to be risk factors for bladder cancer [2]. However, most individuals with these known smoking habits, chemical or environmental exposures never develop bladder cancer while many bladder cancer cases develop among individuals without those known risk factors, suggesting that genetic factors also play an important role in bladder carcinogenesis [3]. Host factors including genetic polymorphisms, have been suggested as risk factors for the development of a variety of cancers, including bladder cancer.

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and methionine synthase (MS) are two enzymes essential for maintaining folate homeostasis. MTHFR catalyzes the irreversible conversion of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, which serves as a substrate for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine with subse-quent synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). Polymorphisms in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene are receiving increasing attention as variants that may potentially influence methyl group metabolism and, thereby, alter chromosome integrity. A common Ala222Val variant (an alanine to valine change) within the N-terminal catalytic domain results in a thermolabile enzyme with with 35-50% reduced activity [4]. Folate deficiency is associated with DNA strand breakage and uracil misincorporation into DNA [5]. Thus, if MTHFR polymorphic variants reduce folate levels by diminishing enzymatic activity, they could enhance the propensity for DNA strand breakage and cancer occurrence [6]. Alternatively, variant MTHFR activity could influence the availability of methyl donors by altering S-adeno-sylmethionine levels, and potentially, the methylation status of key tumor suppressor or promoter genes involved in bladder carcinogenesis [7]. Furthermore, functional polymorphisms in MTHFR could affect the metabolism of other carcinogenic substances that undergo one carbon metabolism such as arsenic [8,9].

Recently, many studies have investigated the role of the MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism in the etiology of bladder cancer susceptibility. However, the results of these studies remain inconsistent. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of all available case–control studies that have been published to assess the effect of the MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism on the risk of bladder cancer.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search in the Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, and Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM) databases updated on March 1, 2013. We combined search terms for MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and bladder cancer risk. Search terms included: (Methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase, MTHFR, Ala222Val, or rs1801133) and bladder cancer. There was no sample size and language limitation. We evaluated all associated publications to retrieve the most eligible literatures. All references cited in the included studies were also hand-searched and reviewed to identify additional published articles not indexed in common databases. Of the studies with overlapping data published by the same authors, only the most recent or complete study was included in this meta-analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies included in this meta-analysis had to meet the following criteria: (1) evaluate the MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and bladder cancer risk, (2) Only the case–control studies were considered; (3) The paper should clearly describe the diagnoses of bladder cancer and the sources of cases and controls; (4) sufficient reported genotypic frequencies in both cases and controls for estimating an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI). The exclusion criteria were: (1) none case–control studies; (2) control population including malignant tumor patients; and (3) duplicated publications.

Data extraction

Information was carefully extracted from all eligible publications independently by two investigators according to the selection criteria. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer assessed the articles. For each of the eligible case–control studies, the following data were collected: the first author’s last name, year of publication, ethnicity, source of the controls, total number of cases and controls, and genotype distributions in cases and controls.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of case–control studies in this meta-analysis was performed using the Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) as recommended by the Cochrane Non-Randomized Studies Methods Working Group [10]. This instrument was developed to assess the quality of nonrandomized studies, specifically cohort and case–control studies. Based on the NOS, case–control studies were judged based on three broad perspectives: selection of study groups (1 criterion), comparability of study groups (4 criteria), and ascertainment of outcome of interest (3 criteria). Given the variability in quality of observational studies found on our initial literature search, we considered studies that met 5 or more of the NOS criteria as high quality [10].

Statistical analysis

We examined the association between MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and the bladder cancer risk by calculating pooled odds ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). We explored the association between (Ala-allele vs Val-allele) comparison and bladder cancer development, as well as homozygote comparison (Ala/Ala versus Val/Val), dominant model [(Ala/Ala + Ala/Val) versus Val/Val)] and recessive model [(Ala/Ala versus Ala/Val + Val/Val)]. The significance of pooled OR was tested by Z test. The χ2-based Q-test was also used to examine the heterogeneity assumption [11]. If studies’ findings only differ by the sampling (P≥0.05), a fixed-effects model could be used to calculate the combined OR. By contrast, if the P value of the Q tests is below 0.05, which suggested that the study results statistically differ by heterogeneous case and sampling, a random-effects model could be more suitable. The significance of the pooled OR was determined by the Z-test, and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

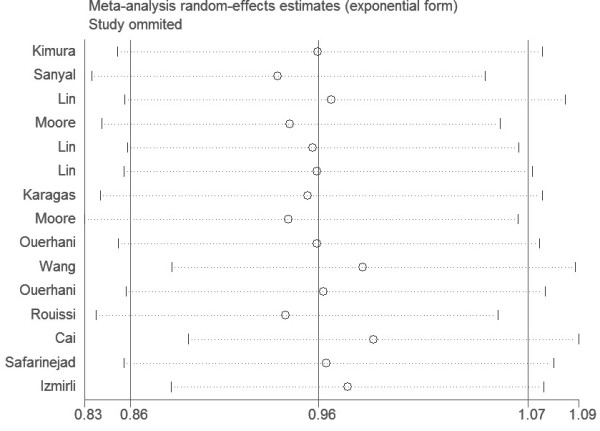

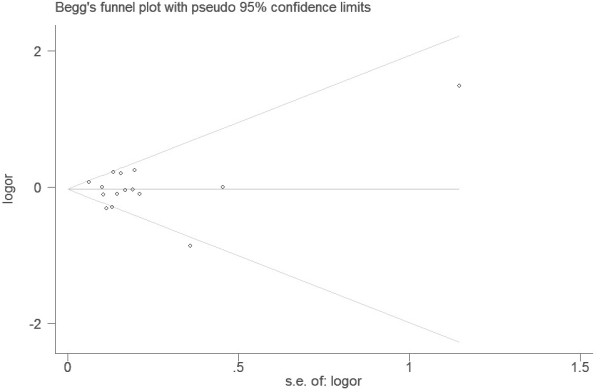

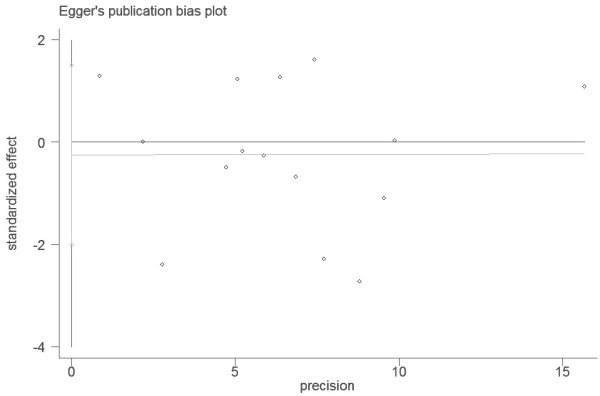

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether our assumptions or decisions have a major effect on the results of the review by omitting each study [12]. Furthermore, subgroup analyses were performed to test whether the effect size varied by the ethnicity and the source of control population. To evaluate the published bias, we used Begg’s [13] and Egger’s [14] formal statistical test and by visual inspection of the funnel plot. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata software (version 12.0; Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX), using two-sided P values.

Results

Study characteristics

In total, 13 publications including 15 case–control studies with 3,570 cases and 3,926 controls met the selection criteria [15-27]. The characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis are listed in Table 1. Among the 15 studies, 5 studies of Caucasians, 5 studies of Asians, 4 studies of Africans and 1 study of mixed population, 8 studies of population-based controls, 7 studies of hospital-based controls. The distribution of the MTHFR Ala222Val genotype in the control groups of these 15 studies was all consistent with HWE (All PHWE values were more than 0.05, Table 1). According to the quality criteria, all the 15 studies were high quality.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of these studies included in this meta-analysis

| First author [Reference] | Year | Ethnicity |

Sample size |

Source of control |

Cases |

Controls |

HWE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala/Ala | Ala/Val | Val/Val | Ala/Ala | Ala/Val | Val/Val | |||||||

| case | control | |||||||||||

| Kimura [15] |

2001 |

Caucasian |

165 |

150 |

HB |

70 |

80 |

15 |

65 |

73 |

12 |

0.17 |

| Sanyal [16] |

2004 |

Caucasian |

309 |

246 |

PB |

173 |

113 |

23 |

121 |

102 |

23 |

0.82 |

| Lin 1[17] |

2004 |

Caucasian |

410 |

410 |

PB |

176 |

183 |

51 |

196 |

164 |

50 |

0.09 |

| Moore [18] |

2004 |

Caucasian |

106 |

109 |

PB |

45 |

42 |

19 |

32 |

59 |

18 |

0.29 |

| Lin 2[17] |

2004 |

Mixed |

17 |

17 |

PB |

16 |

1 |

0 |

13 |

4 |

0 |

0.58 |

| Lin 3[17] |

2004 |

African |

21 |

21 |

PB |

7 |

13 |

1 |

9 |

9 |

3 |

0.76 |

| Karagas [19] |

2005 |

Caucasian |

352 |

551 |

PB |

140 |

171 |

39 |

227 |

245 |

71 |

0.70 |

| Moore [20] |

2006 |

Asian |

1041 |

1049 |

PB |

418 |

478 |

145 |

402 |

486 |

161 |

0.48 |

| Ouerhani [21] |

2007 |

African |

111 |

131 |

HB |

43 |

58 |

10 |

58 |

56 |

17 |

0.55 |

| Wang [22] |

2009 |

Asian |

239 |

250 |

PB |

66 |

129 |

45 |

88 |

132 |

30 |

0.07 |

| Ouerhani [23] |

2009 |

African |

90 |

110 |

HB |

33 |

50 |

7 |

51 |

45 |

14 |

0.42 |

| Rouissi [24] |

2009 |

African |

185 |

191 |

HB |

87 |

86 |

12 |

81 |

90 |

20 |

0.49 |

| Cai [25] |

2009 |

Asian |

312 |

325 |

HB |

82 |

169 |

61 |

113 |

170 |

42 |

0.08 |

| Safarinejad [26] |

2011 |

Asian |

158 |

316 |

HB |

67 |

74 |

17 |

144 |

142 |

30 |

0.56 |

| Izmirli [27] | 2011 | Asian | 54 | 50 | HB | 28 | 22 | 4 | 36 | 14 | 0 | 0.25 |

HB:Hospital-Based Study. PB: Population-Based Study. HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. 1,2,3: Different descent populations in one publication.

Quantitative synthesis

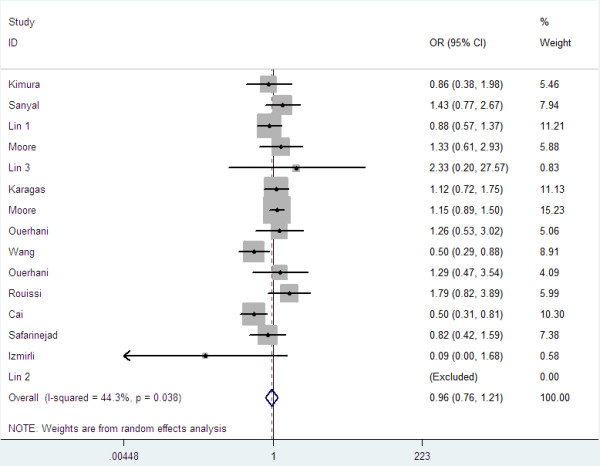

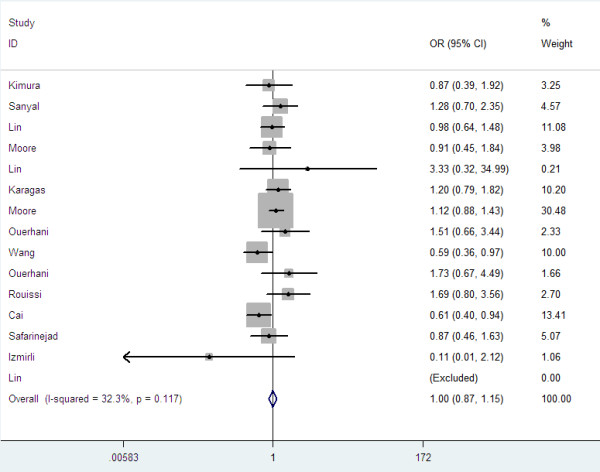

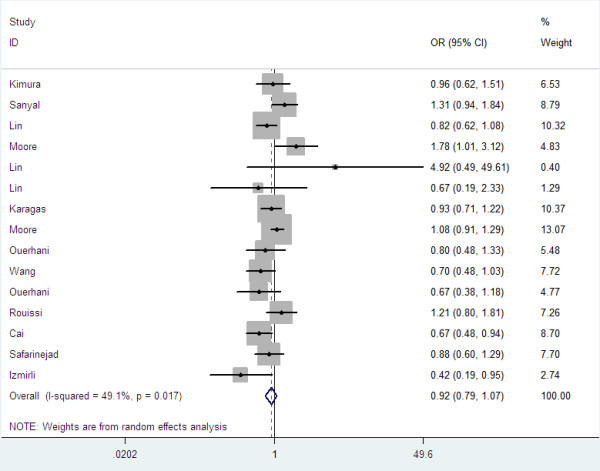

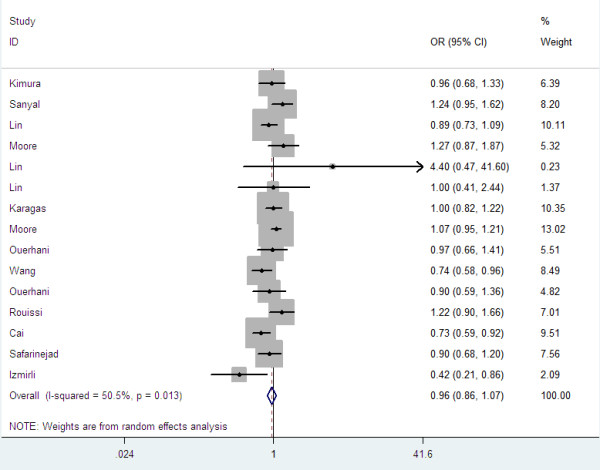

Overall, there was no association between bladder cancer risk and the variant genotypes in different genetic models when all the eligible studies were pooled into the meta-analysis. As show in Table 2, compared with the wild-type homozygote genotype, the homozygote variant genotype Val/Val was not associated with a statistically significant increase risk of bladder cancer (OR=0.96, 95%CI=0.76-1.21, P=0.73, Figure 1). Simultaneously, no significant effects were observed in dominant (OR=1.00, 95%CI=0.87-1.47, P=0.96, Figure 2), recessive models (OR=0.92, 95%CI=0.79-1.07, P=0.28, Figure 3), and Ala allele vs Val allele comparison model (OR=0.96, 95%CI=0.86-1.07, P=0.43, Figure 4). When we analyzed the relationship of MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and bladder cancer risk in different ethnicity subgroup, our data showed that this polymorphism did not contribute to the bladder cancer risk among different descent populations. Subgroup analyses were also performed according to the source of control population. We didn’t observe any significant association both population-based study and hospital-based study in any genetic model using random effect model (Table 2).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis on the association between MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and bladder cancer risk

|

Variables |

Study number |

Sample size |

Test of heterogeneity |

Test of Association |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| case | control | Ph | I2 | OR(95% CL) | P | ||

|

Ala/Ala vs Val/Val |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

15 |

3570 |

3926 |

0.04 |

44.3% |

0.96 (0.76 1.21) |

0.73 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Caucasian |

5 |

1342 |

1466 |

0.70 |

0.0% |

1.07 (0.83 1.38) |

0.59 |

| Asian |

5 |

1804 |

1990 |

0.00 |

74.3% |

0.68 (0.41 1.12) |

0.13 |

| African |

4 |

407 |

453 |

0.91 |

0.0% |

1.50 (0.91 2.45) |

0.11 |

| Mixed population |

1 |

17 |

17 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Source of control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HB |

7 |

1075 |

1273 |

0.07 |

49.3% |

0.90 (0.58 1.39) |

0.62 |

| PB |

8 |

2495 |

2653 |

0.14 |

37.5% |

1.20 (0.79 1.31) |

0.88 |

|

Ala/Ala vs Ala/Val |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

15 |

3570 |

3926 |

0.05 |

41.3% |

0.92 (0.80 1.06) |

0.24 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Caucasian |

5 |

1342 |

1466 |

0.05 |

58.9% |

1.05 (0.81 1.37) |

0.70 |

| Asian |

5 |

1804 |

1990 |

0.15 |

40.4% |

0.86 (0.69 1.06) |

0.15 |

| African |

4 |

407 |

453 |

0.26 |

25.9% |

0.80 (0.56 1.13) |

0.20 |

| Mixed population |

1 |

17 |

17 |

— |

— |

4.92 (0.49 49.61) |

0.18 |

|

Source of control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HB |

7 |

1075 |

1273 |

0.40 |

3.7% |

0.82 (0.68 0.98) |

0.03 |

| PB |

8 |

2495 |

2653 |

0.04 |

51.5% |

1.01 (0.82 1.23) |

0.94 |

|

Ala/Val vs Val/Val |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

15 |

3570 |

3926 |

0.22 |

21.5% |

1.02 (0.85 1.23) |

0.81 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Caucasian |

5 |

1342 |

1466 |

0.69 |

0.0% |

1.07 (0.83 1.37) |

0.60 |

| Asian |

5 |

1804 |

1990 |

0.18 |

36.0% |

0.84 (0.63 1.12) |

0.24 |

| African |

4 |

407 |

453 |

0.86 |

0.0% |

1.86 (1.14 3.03) |

0.01 |

| Mixed population |

1 |

17 |

17 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Source of control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HB |

7 |

1075 |

1273 |

0.14 |

38.6% |

1.08 (0.73 1.59) |

0.71 |

| PB |

8 |

2495 |

2653 |

0.35 |

10.7% |

1.03 (0.85 1.25) |

0.76 |

|

Dominant model |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

15 |

3570 |

3926 |

0.12 |

32.3% |

1.00 (0.87 1.15) |

0.98 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Caucasian |

5 |

1342 |

1466 |

0.86 |

0.0% |

1.07 (0.84 1.35) |

0.58 |

| Asian |

5 |

1804 |

1990 |

0.03 |

63.4% |

0.77 (0.52 1.12) |

0.17 |

| African |

4 |

407 |

453 |

0.94 |

0.0% |

1.68 (1.05 2.69) |

0.03 |

| Mixed population |

1 |

17 |

17 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Source of control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HB |

7 |

1075 |

1273 |

0.09 |

46.0% |

1.00 (0.67 1.49) |

0.99 |

| PB |

8 |

2495 |

2653 |

0.29 |

18.4% |

1.03 (0.84 1.25) |

0.80 |

|

Recessive model |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

15 |

3570 |

3926 |

0.02 |

49.1% |

0.92 (0.79 1.07) |

0.28 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Caucasian |

5 |

1342 |

1466 |

0.07 |

54.4% |

1.06 (0.83 1.34) |

0.66 |

| Asian |

5 |

1804 |

1990 |

0.02 |

67.0% |

0.79 (0.60 1.04) |

0.09 |

| African |

4 |

407 |

453 |

0.33 |

12.9% |

0.90 (0.67 1.21) |

0.49 |

| Mixed population |

1 |

17 |

17 |

— |

— |

4.92 (0.49 49.61) |

0.18 |

|

Source of control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HB |

7 |

1075 |

1273 |

0.20 |

29.8% |

0.92 (0.66 1.01) |

0.06 |

| PB |

8 |

2495 |

2653 |

0.04 |

53.5% |

1.01 (0.83 1.23) |

0.90 |

|

Ala-allele vs Val-allele | |||||||

| Total |

15 |

3570 |

3926 |

0.01 |

50.5% |

0.96 (0.86 1.07) |

0.43 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Caucasian |

5 |

1342 |

1466 |

0.26 |

23.8% |

1.03 (0.90 1.18) |

0.66 |

| Asian |

5 |

1804 |

1990 |

0.00 |

76.5% |

0.81 (0.65 1.03) |

0.08 |

| African |

4 |

407 |

453 |

0.65 |

0.0% |

1.05 (0.86 1.29) |

0.63 |

| Mixed population |

1 |

17 |

17 |

— |

— |

4.40 (0.47 41.60) |

0.20 |

|

Source of control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HB |

7 |

1075 |

1273 |

0.07 |

48.0% |

0.89 (0.74 1.06) |

0.19 |

| PB | 8 | 2495 | 2653 | 0.07 | 47.3% | 1.01 (0.89 1.15) | 0.89 |

HB Hospital-Based Study, PB Population-Based Study, Ph P value of heterogeneit.

Figure 1.

Forest plots for MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and risk of bladder cancer in overall populations (Ala/Ala versus Val/Val).

Figure 2.

Forest plots for MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and risk of bladder cancer in overall populations (Dominant model).

Figure 3.

Forest plots for MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and risk of bladder cancer in overall populations (Recessive model).

Figure 4.

Forest plots for MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and risk of bladder cancer in overall populations (Ala allele vs Val allele).

Sensitivity analysis

In order to compare the sensitivity of this meta-analysis, we conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. A single study involved in this meta-analysis was evaluated each time to reflect the influence of the individual data set to pooled ORs. The results pattern was not impacted by single study in all genetic models, for example, under the allele contrast model (Ala versus Val) was shown in Figure 5. The P for Q test and the I2 value also showed that none of single study affected the heterogeneity of this meta-analysis.

Figure 5.

Sensitive analysis for the MFHTR Ala222Val polymorphism illustrating the influence of each studies on pooled OR (Ala- allele vs Val allele).

Publication bias

Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to assess the publication bias in this meta-analysis. The Funnel plots’ shape of all contrasts did not reveal obvious evidence of asymmetry, and all the P values of Egger’s test were more than 0.05, providing statistical evidence for the funnel plots’ symmetry. For example, this meta-analysis investigated the association between MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and bladder cancer under the allele contrast model (Ala versus Val). Begg’s test for the allele contrast model was shown in Figure 6, and Egger’s test for the allele contrast model was shown in Figure 7. Thus, the above results suggest that publication bias was not evident in this meta-analysis.

Figure 6.

Begg’s funnel plot for assessing the publication bias under the allele contrast model (Ala allele vs. Val allele).

Figure 7.

Egger’s funnel plot for assessing the publication bias under the allele contrast model (Ala allele vs. Val allele).

Discussion

It is wide acknowledged that genetics play an important role in determining cancer risk and association studies have been identified to evaluate cancer susceptibility [28]. However, many associated studies failed to provide convincing evidence of linkage and resulted in contradicting findings. Meta-analysis provided a popular method for combining world literatures across studies to resolve the statistical power and discrepancy problem in associate studies [29]. It was more systematic for its statistical methods than single case–control studies and cohort studies [30-32].

Previous epidemiological studies have evaluated the association between bladder cancer risk and MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism, but with inconclusive results. An initial cohort study suggested a 5.5 fold risk of bladder and kidney cancer combined among 222 Ala>Val variant homozygotes [33]. In contrast, three case–control studies provided the evidence that there was no overall association of MTHFR Ala222Val genotype with bladder cancer [15-17], one study observed a reduced risk among heterozygotes for MTHFR Ala222val [18].

Based on 15 studies providing data on MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism and bladder cancer risk, we conduced a meta-analysis involving in 3,570 cases and 3,926 controls to indicate if this polymorphism was significantly associated with bladder cancer risk. Moreover, we also evaluated the publication bias. The MTHFR Ala222Val genotypes funnel plot was approximately symmetrical. Furthermore, Begg’s and Eggle’s test showed that there was no publication bias in this study. We found that there were no significant associations between this polymorphism and bladder cancer risk in the all genetic models. These results suggested that the MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism might be not contributed to the development of bladder cancer. It has been well known that cancer occurrence and mortality varied by ethnicity and geographic location [34]. In this meta-analysis, all subjects were sub-grouped into four groups (Caucasian, Asian, African and mixed populations). No association of Ala222Val polymorphism with bladder cancer risk was detected in different descent populations. When stratified by source of controls, the similar results were found both in population-based and hospital-based studies.

Some limitations of our meta-analysis should be addressed. Firstly, the numbers of published studies collected in our analysis were not large enough for the comprehensive analysis. Secondly, lacking the original data of the included studies limited our study to further evaluate the potential interactions, since gene-environment and gene-gene interactions may modulate bladder cancer risk. So, a more precise analysis needs to be conducted if individual data such as age and sex are available. Nevertheless, advantages in our meta-analysis should also be acknowledged. A systematic review of the association of MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism with bladder cancer risk is statistically more powerful than any single study. Furthermore, the studies included in our meta-analysis strictly and satisfactory met our selection criteria.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our meta-analysis provided the evidence that the MTHFR Ala222Val polymorphism maybe not contributed to the development of bladder cancer. In addition, further studies with larger sample sizes and careful design are needed to identify this association more comprehensively.

Competing interests

None of the authors have any competing interests to declare.

Authors’ contributions

WX, HZ, and FW carried out the meta-analysis study, drafted the manuscript and involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. HZ and FW participated in the design of the study and revised the manuscript. WX carried out the meta-analysis study and drafted the manuscript. HW participated in the design of the study, drafted the manuscript and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approve the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Wei Xu, Email: weixu_h@163.com.

Haifeng Zhang, Email: haifengzhang_h@163.com.

Fa Wang, Email: fawang_h@163.com.

Honghui Wang, Email: honghuiwang_hlj@163.com.

Funding

No external funding was either sought or obtained for this study.

References

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao Y, Kim WJ, Fujimoto K. Environmental factors promoting bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2009;19:494–499. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32832eb4ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taioli E, Raimondi S. Genetic susceptibility to bladder cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:610–612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, Goyette P, Sheppard CA, Matthews RG, Boers GJ, Den Heijer M, Kluijtmans LA, Van Den Heuvel LP, Rozen R. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10:111–113. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie SJ, Narayanan S, Brand GM, Pirie L, Grant G. Impact of folate deficiency on DNA stability. J Nutr. 2002;132:2444S–2449S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2444S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey LB. Folate, methyl-related nutrients, alcohol, and the MTHFR 677C4T polymorphism affect cancer risk: intake recommendations. J Nutr. 2003;133:3748S–3753S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3748S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie SJ, Narayanan S, Blum S, Pirie L, Brand GM. Folate deficiency in vitro induces uracil misincor-poration and DNA hypomethylation and inhibits DNA excision repair in immortalized normal human colon epithelial cells. Nutr Cancer. 2000;37:245–251. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC372_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDorman EW, Collins BW, Allen JW. Dietary folate deficiency enhances induction of micronuclei by arsenic in mice. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2002;40:71–77. doi: 10.1002/em.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelstein O, Lu X, Le XC, Troen A, Selhub J, Melnyk S, James SJ, Finnell RH. Effects of dietary folate intake and folate binding protein-1 (Folbp1) on urinary speciation of sodium arsenate in mice. Toxicol Lett. 2003;145:167–174. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4274(03)00307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells GA Shea B O'Connell D et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses 2011Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed February 22, 201123888427

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hysong SJ. Meta-analysis: audit and feedback features impact effectiveness on care quality. Med Care. 2009;47(3):356–363. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181893f6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura F, Florl AR, Steinhoff C, Golka K, Willers R, Seifert HH, Schulz WA. Polymorphic methyl group metabolism genes in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Mutat Res. 2001;458:49–54. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5726(01)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S, Festa F, Sakano S, Zhang Z, Steineck G, Norming U, Wijkstrom H, Larsson P, Kumar R, Hemminki K. Polymorphisms in DNA repair and metabolic genes in bladder cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:729–734. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Spitz MR, Wang Y, Schabath MB, Gorlov IP, Hernandez LM, Pillow PC, Grossman HB, Wu X. Polymorphisms of folate metabolic genes and susceptibility to bladder cancer: a case–control study. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1639–1647. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LE, Wiencke JK, Bates MN, Zheng S, Rey OA, Smith AH. Investigation of genetic poly-morphisms and smoking in a bladder cancer case–control study in Argentina. Cancer Lett. 2004;211:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagas MR, Park S, Nelson HH. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) variants and bladder cancer: a population-based case–control study. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2005;208:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LE, Malats N, Rothman N. et al. Polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism and trans-sulfuration pathway genes and susceptibility to bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2452–2458. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouerhani S, Oliveira E, Marrakchi R. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and methionine synthase polymorphisms and risk of bladder cancer in a Tunisian population. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2007;176:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Zhu H, Fu G. et al. Polymorphisms of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and methionine synthase genes and bladder cancer risk: a case–control study with meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2009;9:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10238-008-0013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouerhani S, Rouissi K, Marrakchi R. et al. Combined effect of NAT2, MTR and MTHFR genotypes and tobacco on bladder cancer susceptibility in Tunisian population. Cancer Detect Prev. 2009;32:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouissi K, Ouerhani S, Oliveira E. et al. Polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism pathway genes and risk for bladder cancer in a Tunisian population. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;195:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai DW, Liu XF, Bu RG, Chen XN. et al. Genetic polymorphisms of MTHFR and aberrant promoter hypermethylation of the RASSF1A gene in bladder cancer risk in a Chinese population. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:1882–1889. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. Genetic susceptibility of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene C677T, A1298C, and G1793A polymorphisms with risk for bladder transitional cell carcinoma in men. Med Oncol. 2011;28(1):S398–S412. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izmirli M, Inandiklioglu N, Abat D, Alptekin D, Demirhan O, Tansug Z, Bayazit Y. MTHFR gene polymorphisms in bladder cancer in the Turkish population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1833–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Merikangas K. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science. 1996;273(5281):1516–1517. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Flint J. Meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Trends Genet. 2004;20(9):439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwa Y, Jianqiu C. Association of MHTFR Ala222Val (rs1801133) polymorphism and breast cancer susceptibility: An update meta-analysis based on 51 research studies. Diagnostic Pathology. 2012;7:171. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Q, Qiliu P, Aiping Q, Zhiping C, Liwen L, Yan D, Li X, Juanjuan X, Haiwei L, Taijie L, Shan L, Jinmin Z. Association of COMT Val158Met polymorphism and breast cancer risk: an updated meta-analysis. Diagnostic Pathology. 2012;7:136. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Matos L, Adriana Del G, Carolina M, de Lima Farah M, Auro Del G, da Silva Pinhal M. Expression of ck-19, galectin-3 and hbme-1 in the differentiation of thyroid lesions: systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans BT, Boer JM, Suchiman HE, Cornelisse CJ, Westendorp RG, Kromhout D, Feskens EJ, Slagboom PE. A common variant of the methyle-netetrahydrofolate reductase gene (1p36) is associated with an increased risk of cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1249–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland FD. Ethnic differences in cancer incidence: a marker for inherited susceptibility? Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(Suppl 4):897–900. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]