Abstract

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to develop bonding agent containing a new antibacterial monomer dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate (DMADDM) as well as nanoparticles of silver (NAg) and nanoparticles of amorphous calcium phosphate (NACP), and to investigate the effects of water-ageing for 6 months on dentine bond strength and anti-biofilm properties for the first time.

Methods

Four bonding agents were tested: Scotchbond Multi-Purpose (SBMP) Primer and Adhesive control; SBMP + 5% DMADDM; SBMP + 5% DMADDM + 0.1% NAg; and SBMP + 5% DMADDM + 0.1% NAg with 20% NACP in adhesive. Specimens were water-aged for 1 d and 6 months at 37 °C. Then the dentine shear bond strengths were measured. A dental plaque microcosm biofilm model was used to inoculate bacteria on water-aged specimens and to measure metabolic activity, colony-forming units (CFUs), and lactic acid production.

Results

Dentine bond strength showed a 35% loss in 6 months of water-ageing for SBMP control (mean ± sd; n = 10); in contrast, the new antibacterial bonding agents showed no strength loss. The DMADDM–NAg–NACP containing bonding agent imparted a strong antibacterial effect by greatly reducing biofilm viability, metabolic activity and acid production. The biofilm CFU was reduced by more than two orders of magnitude, compared to SBMP control. Furthermore, the DMADDM–NAg–NACP bonding agent exhibited a long-term antibacterial performance, with no significant difference between 1 d and 6 months (p > 0.1).

Conclusions

Incorporating DMADDM–NAg–NACP in bonding agent yielded potent and long-lasting antibacterial properties, and much stronger bond strength after 6 months of water-ageing than a commercial control. The new antibacterial bonding agent is promising to inhibit biofilms and caries at the margins. The method of DMADDM–NAg–NACP incorporation may have a wide applicability to other adhesives, cements and composites.

Keywords: Antibacterial primer and adhesive, Long-term water-ageing, Dentine bond strength, Quaternary ammonium, methacrylate, Human saliva microcosm biofilm, Caries inhibition

1. Introduction

Secondary caries refers to carious lesions affecting the margins of existing restorations.1,2 It has been widely demonstrated to be the most common reason for replacement of failed restorations in permanent and primary teeth, regardless of the type of restorative material.3–7 Secondary caries showed similar initiation and arrestment processes to primary caries,1 resulting from acids and enzymes produced by dental biofilms.8 Composites are popular tooth cavity filling materials,9–14 and composite restorations are bonded to the tooth structure using adhesives.15–22 Therefore, efforts have been made to develop antibacterial composites and adhesives that could kill bacteria and reduce or avoid the formation of biofilms.23–27 Antibacterial quaternary ammonium methacrylates (QAMs) was synthesized and incorporated into dental resins.28–33 In addition, antibacterial adhesives were proposed to be beneficial when the clinical situation prevented complete caries removal.34

In pioneering work on the development of antibacterial restoratives containing QAMs, 12-methacryloyloxydodecyl-pyridinium bromide (MDPB) was incorporated into composites, 24 primer and adhesive.23–35 Methacryloxylethyl cetyl dimethyl ammonium chloride (DMAE-CB) was also developed and served as a component for antibacterial bonding agents.25,36 Another study developed the poly(quaternary ammonium salt)-containing polyacid to formulate the light-curable glass-ionomer cements.26 The antibacterial activity of quaternary ammonium polyethylenimine nanoparticles embedded in dental composite resins was also studied.37 A quaternary ammonium dimethacrylate (QADM) was synthesized and incorporated into dental composites,30 primer,31 and adhesive,38 which substantially reduced biofilm viability and acid production. Regarding the antimicrobial mechanism, when the negatively charged bacterial cell contacts the positively charged (N+) sites of the QAM resin, the electric balance of the cell membrane could be disturbed, and the bacterium could explode under its own osmotic pressure.37 There have been only a small number of reports on the development of antibacterial resins, and more efforts are needed to investigate QAM resin processing, anti-biofilm properties, and long-term durability. Recently, in our pilot study,39 a new quaternary ammonium monomer dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate (DMADDM) was synthesized and showed much stronger antibacterial effect than the previous QADM. DMADDM possessed a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) that were three orders of magnitude lower than QADM.39 However, the long-term antibacterial effects of primer and adhesive containing DMADDM have not been investigated, and the dentine bond strength of primer and adhesive containing DMADDM after long-term water-ageing needs to be determined.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to investigate the effects of water-ageing on (1) the antibacterial effects of primer and adhesive containing the new DMADDM; and (2) the dentine bond strength of DMADDM-containing primer and adhesive. Besides DMADDM, nanoparticles of silver (NAg) were incorporated into bonding agent to further enhance the antibacterial potency, and nanoparticles of amorphous calcium phosphate (NACP) were incorporated into adhesive for remineralization. The antibacterial effects were examined with a microcosm model inoculated using human saliva. It was hypothesized that: (1) the new bonding agent containing DMADDM, NAg and NACP would not show a decrease in dentine bond strength during 6 months of water-ageing, while a commercial bonding agent control would show substantial bond strength loss; (2) The new bonding agent containing DMADDM, NAg and NACP would not show a decrease in antibacterial activity in the 6-month water-ageing; (3) The DMADDM–NAg–NACP containing bonding agents would greatly reduce biofilm viability, acid production, and colony-forming units (CFUs), compared to commercial control.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Incorporation of DMADDM into bonding agent

The new antibacterial monomer DMADDM with an alkyl chain length of 12 was synthesized using a modified Menschutkin reaction method. This method, in which a tertiary amine group is reacted with an organo-halide, is desirable because the reaction products were generated at quantitative amounts and required no further purification.27,31,38 For DMADDM, the organo halide was 2-bromoethyl methacrylate (BEMA), and the tertiary amine was 1-(dimethylamino)docecane (DMAD).39 Ten millimole of BEMA (Monomer-Polymer and Dajac Labs, Trevose, PA), 10 mmol DMAD (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan), and 3 g of ethanol were put into a 20 mL scintillation vial. The vial was capped and stirred with a magnetic stir bar at 70 °C for 1 d. When the reaction was completed, the ethanol solvent was evaporated, yielding DMADDM as a clear, colourless, and viscous liquid. The reaction and product of DMADDM were verified via Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet 6700, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) as reported in a pilot study.39

Scotchbond Multi-Purpose Adhesive and Primer (referred as “SBMP”) (3M, St. Paul, MN) were used as the parent bonding system to test the effect of incorporation of antibacterial agents. According to the manufacturer, SBMP adhesive contained 60–70% of bisphenol A diglycidyl methacrylate (BisGMA) and 30–40% of 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), tertiary amines and photo-initiator. SBMP primer contained 35–45% of HEMA, 10–20% of a copolymer of acrylic and itaconic acids, and 40–50% water. SBMP etchant contained 37% of phosphoric acid. DMADDM was incorporated into SBMP primer at a mass fraction of DMADDM/(SBMP primer + DMADDM) = 5%. The 5% was selected following a previous study.35 Similarly, DMADDM was incorporated into SBMP adhesive at 5% mass fraction.

2.2. Incorporation of NAg and NACP into bonding agent

Silver 2-ethylhexanoate (Strem, Newburyport, MA) of 0.1 g was dissolved into 0.9 g of 2-(tert-butylamino)ethyl meth-acrylate (TBAEMA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The Ag solution was mixed with SBMP adhesive or SBMP primer at a silver 2-ethylhexanoate mass fraction of 0.1%, following a previous study.38 TBAEMA was chosen because it improved the solubility of Ag in the resin solution by forming Ag-N coordination bonds.40 TBAEMA contains reactive methacrylate groups, and can be chemically incorporated into a dental resin upon photopolymerization. 30,40

Composites containing NACP could release calcium (Ca) and phosphate (P) ions and remineralize tooth lesions.41–43 NACP, Ca3(PO4)2, were synthesized using a spray-drying technique.41 Briefly, calcium carbonate and dicalcium phosphate anhydrous were dissolved in acetic acid to produce Ca and P concentrations of 8 mmol/L and 5.333 mmol/L, respectively, thus yielding a Ca/P molar ratio = 1.5, the same as that for ACP. This solution was sprayed into a heated chamber, and an electrostatic precipitator collected the dried particles. This yielded NACP with a mean particle size of 116 nm.41 NACP were incorporated into the SBMP adhesive, but not into the primer, as preliminary study showed that adding NACP into primer decreased the dentine bond strength. NACP were incorporated into SBMP adhesive at NACP/(adhesive + NACP) = 20% mass fraction. Previous studies showed that this mass fraction could release significant levels of Ca and P ions,41 while having no adverse effect on dentine bond strength.44

Therefore, the following four bonding systems were investigated:

SBMP adhesive and primer control (designated “SBMP control”);

SBMP adhesive and primer each + 5% DMADDM (designated “DMADDM”);

SBMP adhesive and primer each + 5% DMADDM + 0.1% NAg (“DMADDM + NAg”);

SBMP adhesive + 5% DMADDM + 0.1% NAg + 20% NACP; SBMP primer + 5% DMADDM + 0.1% NAg (“DMADDM + NAg + NACP”).

2.3. Dentine shear bond testing

Extracted caries-free human third molars were used, which was approved by the University of Maryland. The molars were first sawed to remove the crowns (Isomet, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL), then ground perpendicularly to their longitudinal axes on 320 grit SiC paper until occlusal enamel was completely removed. After etching for 15 s and rinsing with water,45 the dentine surface was brushed with primer, and the solvent of primer was evaporated with an air stream. The adhesive was then applied and light-cured for 10 s (Optilux-VCL401, Demetron, Danbury, CT). A stainless-steel iris with a central opening having a diameter of 4 mm and a thickness of 1.5 mm, was held against the adhesive-treated dentine surface.45 The opening was filled with a composite (TPH, Dentsply, Milford, DE) and light-cured for 60 s. The bonded specimens were stored in distilled water at 37 °C. Each of the aforementioned four groups was randomly divided for water-ageing at 1 d and 6 months, respectively. This constituted a 4 × 2 full factorial design with four bonding agents and two immersion times. Ten teeth for each condition (n = 10) required 80 bonded teeth. After water-ageing, the dentine shear bond strength, SD, was measured following a previous method.45 A chisel was held parallel to the composite–dentine interface, and loaded via a computer-controlled Universal Testing Machine (MTS, Eden Prairie, MN) at 0.5 mm/min until the composite–dentine bond failed. SD was calculated as: SD = 4P/(πd2), where P is the load at failure, and d is the diameter of the composite.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were used to examine the dentine–adhesive interface. The bonded teeth were cut longitudinally. The sections were treated with 50% phosphoric acid and 10% NaOCl,31 then gold-coated and examined via SEM (Quanta 200, FEI, Hillsboro, OR). For TEM, thin sections with an approximate thickness of 120 μm were cut and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde following a previous study.46 Samples were embedded in epoxy (Spurr’s, Electron Microscopy Sciences, PA). Ultra-thin sections with approximate thickness of 100 nm were cut using a diamond knife (Diatome, Bienne, Switzerland) with an ultra-microtome (EM-UC7, Leica, Germany). The non-demineralized sections were examined in TEM (Tecnai-T12, FEI).

2.4. Saliva collection for the dental plaque microcosm biofilm model

The dental plaque microcosm biofilm model was approved by University of Maryland. This model has the advantage of maintaining much of the complexity and heterogeneity of in vivo plaques.47 Saliva was collected from a healthy adult donor having natural dentition without active caries or periopathology, and without the use of antibiotics within the past three months.31,38 The donor did not brush teeth for 24 h and stopped any food/drink intake for at least 2 h prior to donating saliva. Stimulated saliva was collected during parafilm chewing and kept on ice. Saliva was diluted in sterile glycerol to a saliva concentration of 70% and stored at −80 °C. Aliquots of 1 mL were stored at −80 °C for subsequent use.31,38

2.5. Resin specimens for biofilm experiments

Primer/adhesive/composite tri-layer disks were fabricated following previous studies.31,38 Each primer was brushed on a glass slide, then a polyethylene mould (inner diameter = 9 mm, thickness = 2 mm) was placed on the glass slide. After drying with a stream of air, 10 μL of an adhesive was applied and cured for 20 s with Optilux. Then, the composite (TPH) was placed on the adhesive to fill the mould and cured for 1 min (Triad 2000, Dentsply, Milford, DE).31,38 The cured specimens were agitated in water for 1 h to remove any uncured monomers, following a previous study.23 The specimens were then immersed in distilled water at 37 °C for 1 d or 6 months. The water was changed every week. After water-ageing, the specimens were inoculated with biofilms to examine their antibacterial activity.

2.6. Bacteria inoculum and live/dead biofilm staining

The disks were sterilized with ethylene oxide sterilizer (Anprolene AN 74i, Andersen, Haw River, NC) following the manufacturer’s instructions.38 The saliva–glycerol stock was added, with 1:50 final dilution, to a growth medium as inoculum. The growth medium contained mucin (type II, porcine, gastric) at a concentration of 2.5 g/L; bacteriological peptone, 2.0 g/L; tryptone, 2.0 g/L; yeast extract, 1.0 g/L; NaCl, 0.35 g/L, KCl, 0.2 g/L; CaCl2, 0.2 g/L; cysteine hydrochloride, 0.1 g/L; haemin, 0.001 g/L; vitamin K1, 0.0002 g/L, at pH 7.48 Each disk was placed into a well of a 24-well plate with the primer side facing up. Each well was filled with 1.5 mL of inoculum, and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After 8 h, each specimen was transferred into a new 24-well plate with 1.5 mL fresh medium, and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 16 h. Then, each specimen was transferred into a new 24-well plate with 1.5 mL fresh medium, and incubated for 1 d. This totaled 2 d of incubation, which was shown to form biofilms on resins.31,38

Specimens with biofilms were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and live/dead stained using the BacLight live/dead bacterial viability kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Imaging was performed via confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM 510, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Four randomly chosen fields of view were photographed from each disk, yielding a total of 16 images for each bonding agent at each water-ageing period.

2.7. MTT assay of metabolic activity

A MTT assay (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was used to examine the metabolic activity of biofilms.27,30 MTT is a colorimetric assay that measures the enzymatic reduction of MTT, a yellow tetrazole, to formazan. Disks with 2d biofilms (n = 6) were transferred to a new 24-well plate, and 1 mL of MTT dye (0.5 mg/mL MTT in PBS) was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 1 h. During the incubation, metabolically active bacteria metabolized the MTT, a yellow tetrazole, and reduced it to purple formazan inside the living cells. Disks were then transferred to new 24-well plates, and 1 mL of dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) was added to solubilize the formazan crystals. The plates were incubated for 20 min with gentle mixing at room temperature. Two hundred microlitres of the DMSO solution from each well was collected, and its absorbance at 540 nm was measured via a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). A higher absorbance means a higher formazan concentration, which is related to more metabolic activity in the biofilm on the surface of different groups of adhesive and primer.

2.8. Lactic acid production by biofilms adherent on resin disks

Disks with 2 d biofilms (n = 6) were rinsed with cysteine peptone water (CPW) to remove loose bacteria, and then transferred to 24-well plates containing 1.5 mL buffered-peptone water (BPW) plus 0.2% sucrose. The specimens were incubated for 3 h to allow the biofilms to produce acid. The BPW solutions were collected for lactate analysis using an enzymatic method.31,38 The 340-nm absorbance of BPW was measured with the microplate reader. Standard curves were prepared using a standard lactic acid (Supelco Analytical, Bellefonte, PA).30,31,38

2.9. Colony-forming unit (CFU) counts of biofilms adherent on resin disks

Disks with biofilms were transferred into tubes with 2 mL CPW, and the biofilms were harvested by sonication and vortexing via a vortex mixer (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA).31,38 Three types of agar plates were prepared. First, tryptic soy blood agar culture plates were used to determine total microorganisms. 31,38 Second, mitis salivarius agar (MSA) culture plates, containing 15% sucrose, were used to determine total streptococci.31,38,49 This is because MSA contains selective agents crystal violet, potassium tellurite and trypan blue, which inhibit most gram-negative bacilli and most gram-positive bacteria except streptococci, thus enabling streptococci to grow.49 Third, cariogenic mutans streptococci are known to be resistant to bacitracin, and this property is often used to isolate mutans streptococci from the highly heterogeneous oral microflora. Hence, MSA agar culture plates plus 0.2 units of bacitracin per mL was used to determine mutans streptococci.31,38,50 The bacterial suspensions were serially diluted and spread onto agar plates for CFU analysis.31,38

2.10. Statistical analysis

One-way and two-way analyses-of-variance (ANOVA) were performed to detect the significant effects of variables. Tukey’s multiple comparison was used to compare the data at p of 0.05.

3. Results

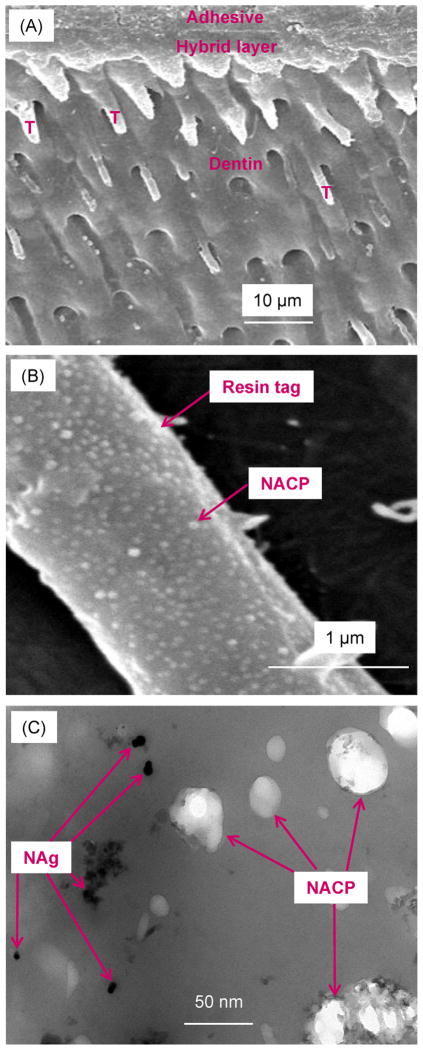

SEM and TEM images of typical dentine–adhesive interfaces are shown in Fig. 1(A) and (B) SEM at low and high magnification, respectively, and (C) TEM. Numerous resin tags were visible in (A). Resin tags were formed by adhesive filling into dentinal tubules. The hybrid layer between the adhesive and the underlying mineralized dentine was formed via bonding agent infiltrating into the demineralized collagen layer. Some resin tags appeared shorter than others. This was because during sample preparation, the sectioned surface was not exactly parallel to the long axis of dentinal tubules. Hence some tubules were intersected by the cut and appeared short on the two-dimensional image. The example shown in (A) was for specimens with DMADDM, NAg and NACP. All four groups had similar features. A higher magnification of a resin tag is shown in (B) for a sample with NACP. A representative TEM image at a higher magnification is shown in (C) inside a resin tag for the DMADDM + NAg + NACP group. The NAg were formed in the resin tags, and the NACP were successfully flowed with the adhesive resin into the dentinal tubules.

Fig. 1.

Representative images of dentine–adhesive interface for specimens after 1 d immersion: (A and B) SEM images at low and high magnification, and (C) TEM image. “T” in (A) indicates resin tags. The example in (A) is for group DMADDM + NAg + NACP; other groups had similar features. (B) Higher magnification for DMADDM + NAg + NACP shows NACP inside a resin tag. (C) At an even higher magnification in TEM, both NACP and NAg are visible inside resin tags. Hence, both NACP and NAg were successfully flowed into dentinal tubules.

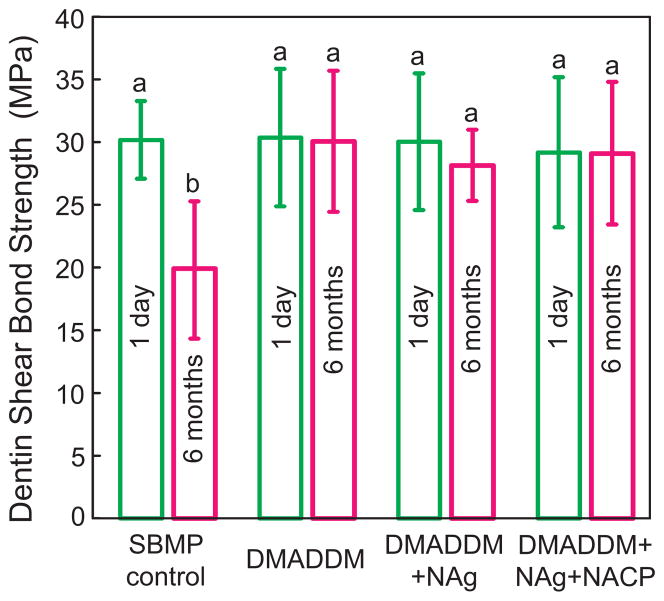

Dentine shear bond strengths are plotted in Fig. 2 (mean ± sd; n = 10). All the strengths were not significantly different from each other (p > 0.1), except the control group after 6 months of water-ageing, which was significantly lower than others (p < 0.05). There was a 35% strength loss for the commercial bonding agent during 6 months’ water-ageing. However, there was no strength loss for the antibacterial bonding agents incorporating DMADDM, NAg, and NACP.

Fig. 2.

Dentine shear bond strengths using extracted human molars (mean ± sd; n = 10). Values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05). There was a 35% loss in bond strength for commercial bonding agent in 6 months’ water-ageing. However, there was no bond strength loss for the new antibacterial bonding agents incorporating DMADDM, NAg, and NACP.

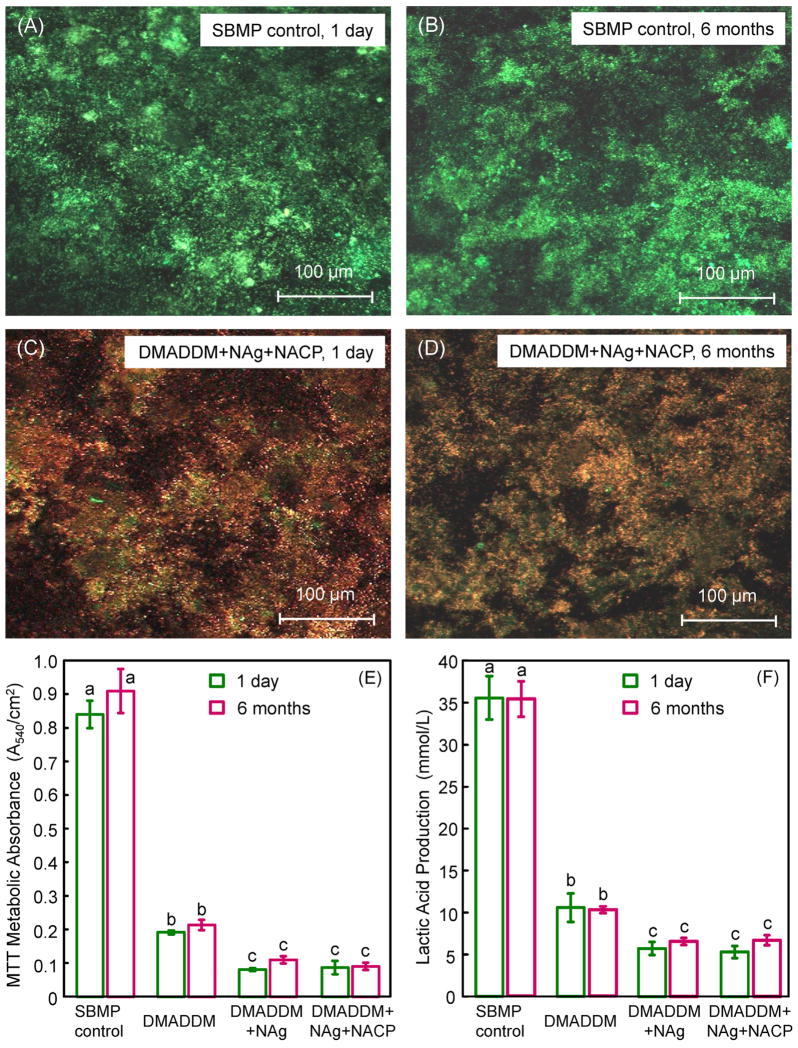

Fig. 3(A–D) shows representative confocal laser scanning microscopy of live/dead images. SBMP control was fully covered by primarily live bacteria, and there was no noticeable difference between 1 d and 6 months. The group DMADDM + NAg + NACP had mostly dead bacteria, and there was no noticeable difference between 1 d and 6-month samples, indicating that the antibacterial activity was not lost in water- ageing for 6 months. The other groups (DMADDM, and DMADDM + NACP) had images similar to (C) and (D) (not included). The total area of biofilm coverage, (live + dead bacteria area)/entire image area, was measured (mean ± sd; n = 5). This yielded (88.3 ± 7.4)% for SBMP control at 1 d, vs. (77.9 ± 6.6)% for DMADDM + NAg + NACP (p > 0.1). At 6 months, the total area of biofilm coverage was (90.4 ± 8.1)% for SBMP control, vs. (78.6 ± 9.1)% for DMADDM + NAg + NACP (p > 0.1). These data show that the total biofilm coverage on the resin disks was similar among the different groups, but there were less live bacteria and more dead bacteria on the antibacterial resins, as shown in the images in Fig. 3(A–D).

Fig. 3.

Results of live/dead assay, MTT assay, and lactic acid production. (A and B) Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy live/dead images for SBMP control at 1 d and 6 months, respectively. (C and D) Live/dead images of biofilms on DMADDM + NAg + NACP at 1 d and 6 months, respectively. DMADDM and DMADDM + NACP had images similar to (C) and (D) (not shown). The new antibacterial bonding agent had mostly dead bacteria, while SBMP had primarily live bacteria. (E) Metabolic activity, and (F) lactic acid production (mean ± sd; n = 6). The strong antibacterial effect was maintained after water-ageing for 6 months.

Quantitative metabolic activity via the MTT assay is plotted in Fig. 3(E) (mean ± sd; n = 6). (1) Adding DMADDM into the bonding agent greatly reduced the biofilm metabolic activity. (2) Adding NAg further significantly decreased the metabolic activity. (3) Adding NACP (which would gain a remineralizing capability as shown previously) did not interfere with the antibacterial activity. (4) Water- ageing for 6 months did not reduce the antibacterial efficacy compared to 1 d (p > 0.1). The lactic acid production by biofilms in Fig. 3(F) showed a similar trend. These results demonstrated a durable antibacterial activity of bonding agents containing DMADDM and NAg that was retained in the 6 months’ water- ageing.

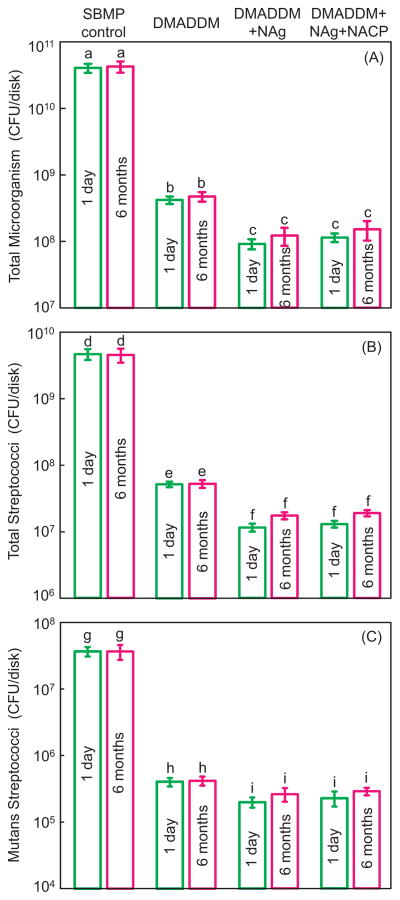

The biofilm CFU counts are plotted in Fig. 4 for (A) total microorganisms, (B) total streptococci, and (C) mutans streptococci (mean ± sd; n = 6). DMADDM, DMADDM + NAg and DMADDM + NAg + NACP greatly decreased the biofilm CFU (p < 0.05). The incorporation of dual agents (DMADM + NAg) in primer and adhesive had a significantly stronger antibacterial effect than DMADDM alone (p < 0.05). The antibacterial potency did not decrease over time, since there was no significant difference of CFU before and after 6 months of water- ageing for each group (p < 0.05). DMADDM + NAg and DMADDM + NAg + NACP reduced the biofilm CFU of the commercial SBMP control by more than two orders of magnitude.

Fig. 4.

CFU of biofilms adherent on cured bonding agent disks: (A) total microorganisms, (B) total streptococci, and (C) mutans streptococci (mean ± sd; n = 6). Each plot has four groups. The names of the four groups are listed on the top of the figure. DMADDM + NAg and DMADDM + NAg + NACP reduced the biofilm CFU of the commercial SBMP control by more than two orders of magnitude. In each plot, values with dissimilar letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this study, novel DMADDM–NAg–NACP containing bonding agents were developed that demonstrated an excellent dentine bond strength durability, and maintained a potent anti-biofilm activity in 6 months of water-ageing for the first time. DMADDM was an antibacterial quaternary ammonium monomer with an alkyl chain length of 12 which possessed a strong antibacterial potency.39 QAMs had bacteriolysis effects, because their positively charged quaternary amine N+ can attract the negatively charged cell membrane of bacteria, which could disrupt the cell membrane and cause cytoplasmic leakage.37,51 Our recent study showed that by increasing the alkyl chain length from 6 to 12, the antibacterial potency of the QAMs was strongly enhanced.39 However, that pilot study did not investigate the effect of water-ageing on antibacterial activity or dentine bond strength. The present study showed that the DMADDM–NAg–NACP containing bonding agents could achieve a long-term antibacterial capability by substantially reducing biofilm viability, CFU, and acid production after 6 months of water-ageing, while possessing a much higher long-term bond strength than that of the commercial control. Therefore, it is promising to use DMADDM–NAg–NACP containing bonding agents to combat both residual bacteria in the tooth cavity and invading bacteria at the margins to inhibit caries. The results of the present study suggest that DMADDM, NAg and NACP may be promising for incorporation into other adhesives and restoratives.

While most dental adhesives exhibit excellent initial and short-term bonding strength, the durability and stability of resin-bonded interfaces still remain a challenge.52,53 Previous studies reported the progressive decrease in resin –dentine bond strength occurring after ageing.54–56 The degradation of the hybrid layer at the dentine–adhesive interface was believed to be the primary reason, which was caused by several physical and chemical factors, including the hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation of the exposed collagen as well as the adhesive resin.53 Since some water sorption was inevitable due to the polar ether-linkages and/or hydroxyl groups in adhesive system,57 this may result in hydrolysis of the hydrophilic resin components.17,55 In addition, bacterial enzymes and host-derived matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) may also be involved in the degradation of the hybrid layer.18 MMPs could be released and activated during dentine bonding, causing breakdown of the unprotected collagen fibrils in the hybrid layer.16,18,58,59 The breakdown of collagen may increase the water content, causing further collagen degradation and inducing deterioration of the durability of dentine bonding.53 Furthermore, some uncured monomers and break-down products of the bonded interface can elute and thus weaken the bond strength.16 Chlorhexidine (CHX) has been found to have MMP inhibitory and anti-enzyme properties.60 Collagen degradation of demineralized dentine was almost completely inhibited via CHX.61,62 However, CHX is water-soluble and, when incorporated into the adhesive resin, may elute to decrease its long-term anti-MMP effectiveness. 63 In contrast, QAMs are co-polymerized in adhesive, and are thus immobilized, which can potentially provide durable MMP inhibition. It was reported, both in vivo and in vitro, in a one-year study that bond strengths decreased with time for a control adhesive, but not for an antibacterial adhesive that contained MDPB.64 Still, the long-term inhibition activity of QAMs requires further investigation.63 In the present study, a new DMADDM was incorporated into a bonding agent. The dentine shear bond strength of the control group substantially decreased after 6 months of water-ageing. However, the new antibacterial bonding agents showed no reduction on bond strength. This was likely because the antibacterial agent copolymerized with and immobilized in the adhesive monomers, and was not leached out and lost over time, thereby exerting a lasting anti-biofilm and anti-MMP effects. Further studies are needed to validate the anti-MMP effect of the new bonding agent and the relationship with the dentine bond strength durability in long-term ageing.

The bonding agent containing DMADDM, NAg and NACP exhibited a long-term antibacterial performance by substantially reducing biofilm viability, CFU, and acid production after water- ageing. Inclusion of antibacterial agents into the adhesive system is promising for caries inhibition.34 This is because recurrent caries at the tooth-restoration margins is the main reason for restoration failure. By inhibiting the formation of biofilms which produce the acids and enzymes to cause tooth decay, these antibacterial agents could combat the recurrent caries. When the clinical situation prevents complete caries removal and in minimal intervention dentistry,65 more carious tissues with residual bacteria could be left in the prepared tooth cavity. Uncured dentine primer with DMADDM monomer has direct contact with the tooth structure and can flow into dentinal tubules, which is useful in killing the residual bacteria. During service, there are also new bacteria invading the tooth-composite margins because of microgaps at the tooth-restoration interfaces.66 It is therefore advantageous to use adhesive copolymerized with DMADDM to inhibit bacterial invasion. The present study showed for the first time that the bonding agent containing DMADDM, NAg and NACP had strong antibacterial activity that was maintained in the 6 months of water-ageing. While the copolymerization and covalent bonding of the DMADDM with the polymer network would indicate this to be a long-lasting antibacterial bonding system, a water-ageing study longer than 6 months is needed.

Ag is an effective antimicrobial agent.67,68 Previous studies showed that Ag has good biocompatibility and low toxicity to human cells, has long-term antibacterial effects,67 and causes less bacterial resistance than antibiotics.69 Ag has been incorporated to develop antibacterial dental composites. 31,40,70 In the present study, the Ag salt was reduced to NAg in the resin in situ to avoid agglomeration. The NAg had a small particle size with a high specific surface area, which imparted a strong antibacterial activity at a 0.1% mass fraction.38 This low concentration of NAg did not compromise the resin colour and mechanical properties. Indeed, groups 2 and 3 had similar dentine bond strengths (Fig. 2). The antimicrobial mechanism of Ag was suggested to be that the vital enzymes of bacteria could interact with and be inactivated by Ag ions, causing the loss of the DNA replication ability and cell death.68

Comparison of group 3 with group 4 indicated that NACP had no antibacterial activity against biofilms. The purpose of incorporating NACP into the adhesive was to impart a remineralizing capability. A previous study showed that NACP nanocomposite was advantageous in that it could release high levels of Ca and P ions at relatively low NACP filler levels because of the high surface area of the nanoparticles.41 By increasing the saliva calcium-phosphate concentrations to levels higher than those in natural saliva, the remineralization of tooth lesions can be significantly promoted. Indeed, recent studies showed that the NACP nanocomposite effectively remineralized enamel lesions in vitro,43 and inhibited secondary caries formation in a human in situ study.43 The present study focused on the effects of the 6 months of water-ageing treatment on dentine bond strength and antibacterial properties, without investigating the remineralization of tooth lesions via the NACP-containing bonding agent. Further study is needed to address this issue. Further study is also needed to investigate the incorporation of DMADDM, NAg and NACP in other bond agents, pit and fissure sealants, orthodontic bracket cements, and composites with antibacterial and remineralizing capabilities to inhibit caries.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the durability of bonding agents containing a new antibacterial monomer DMADDM, NAg and NACP in water-ageing for the first time. While a commercial bonding agent lost 35% of its dentine bond strength in 6 months of water-ageing, the new antibacterial bonding agent containing DMADDM, NAg and NACP showed no loss in dentine bond strength in water-ageing. Furthermore, the biofilm viability, metabolic activity and lactic acid production were substantially reduced via the new bonding agent. Compared to control, bonding agent containing DMADDM and NAg decreased the biofilm CFU by more than two orders of magnitude. There was no significant decrease in antibacterial activity in water-ageing for 6 months. Therefore, DMADDM, NAg and NACP could impart three benefits: protecting dentine bond strength from degrading in long-term water-ageing; potent antibacterial activity that was long-lasting; and remineralization. The bonding agent containing DMADDM, NAg and NACP is promising for durable dentine bonding to help inhibit biofilm acids and secondary caries. The method of DMAMD + NAg + NACP incorporation may have a wide applicability to other bonding systems, cements, and composites.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Joseph M. Antonucci, Nancy J. Lin and Sheng Lin-Gibson of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and Ashraf F. Fouad of the University of Maryland School of Dentistry for discussions. We thank Dr. Huaibing Liu at Caulk/Dentsply (Milford, DE) for donating the TPH composite. This study was supported by the School of Stomatology at the Capital Medical University in China (K.Z.), NIH R01DE17974 (HX) and a seed fund from the University of Maryland School of Dentistry (H.X.).

References

- 1.Mjor IA, Toffenetti F. Secondary caries: a literature review with case reports. Quintessence International. 2000;31:165–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidd EA. Diagnosis of secondary caries. Journal of Dental Education. 2001;65:997–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deligeorgi V, Mjor IA, Wilson NH. An overview of reasons for the placement and replacement of restorations. Primary Dental Care. 2001;8:5–11. doi: 10.1308/135576101771799335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Totiam P, Gonzalez-Cabezas C, Fontana MR, Zero DT. A new in vitro model to study the relationship of gap size and secondary caries. Caries Research. 2007;41:467–73. doi: 10.1159/000107934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asghar S, Ali A, Rashid S, Hussain T. Replacement of resin-based composite restorations in permanent teeth. Journal of College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 2010;20:639–43. doi: 10.2010/JCPSP.639643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chrysanthakopoulos NA. Placement, replacement and longevity of composite resin-based restorations in permanent teeth in Greece. International Journal of Dentistry. 2012;62:161–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2012.00112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordan VV, Riley JL, 3rd, Geraldeli S, Rindal DB, Qvist V, Fellows JL, et al. Repair or replacement of defective restorations by dentists in The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2012;143:593–601. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi N, Nyvad B. The role of bacteria in the caries process: ecological perspectives. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90:294–303. doi: 10.1177/0022034510379602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts DC, Marouf AS, Al-Hindi AM. Photo-polymerization shrinkage-stress kinetics in resin-composites: methods development. Dental Materials. 2003;19:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch CD, Frazier KB, McConnell RJ, Blum IR, Wilson NHF. State-of-the-art techniques in operative dentistry: contemporary teaching of posterior composites in UK and Irish dental schools. British Dental Journal. 2010;209:129–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond JL. Degradation, fatigue, and failure of resin dental composite materials. Journal of Dental Research. 2008;87:710–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan Q, Sheffield J, McCool J, Baran GR. Light curable dental composites designed with colloidal crystal reinforcement. Dental Materials. 2008;24:1694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferracane JL. Resin composite – state of the art. Dental Materials. 2011;27:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milward PJ, Adusei GO, Lynch CD. Improving some selected properties of dental polyacid-modified composite resins. Dental Materials. 2011;27:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer P, Wang Y. Adhesive phase separation at the dentin interface under wet bonding conditions. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2002;62:447–56. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto M, Ohno H, Sano H, Tay FR, Kaga M, Kudou Y, et al. Micromorphological changes in resin–dentin bonds after 1 year of water storage. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2002;63:306–11. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Water treeing—a potential mechanism for degradation of dentin adhesives. American Journal of Dentistry. 2003;16:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pashley DH, Tay FR, Yiu C, Hashimoto M, Breschi L, Carvalho RM, et al. Collagen degradation by host-derived enzymes during aging. Journal of Dental Research. 2004;83:216–21. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coelho-De-Souza FH, Camacho GB, Demarco FF, Powers JM. Fracture resistance and gap formation of MOD restorations: influence of restorative technique, bevel preparation and water storage. Operative Dentistry. 2008;33:37–43. doi: 10.2341/07-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park J, Ye Q, Topp E, Misra A, Kieweg SL, Spencer P. Water sorption and dynamic mechanical properties of dentin adhesives with a urethane-based multifunctional methacrylate monomer. Dental Materials. 2009;25:1569–75. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Godoy F, Kramer N, Feilzer AJ, Frankenberger R. Long-term degradation of enamel and dentin bonds: 6-year results in vitro vs. in vivo. Dental Materials. 2010;26:1113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blum IR, Hafiana K, Curtis A, Barbour ME, Attin T, Lynch CD, et al. The effect of surface conditioning on the bond strength of resin composite to amalgam. Journal of Dentistry. 2012;40:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imazato S, Ehara A, Torii M, Ebisu S. Antibacterial activity of dentine primer containing MDPB after curing. Journal of Dentistry. 1998;26:267–71. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imazato S. Bio-active restorative materials with antibacterial effects: new dimension of innovation in restorative dentistry. Dental Materials Journal. 2009;28:11–9. doi: 10.4012/dmj.28.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li F, Chen J, Chai Z, Zhang L, Xiao Y, Fang M, et al. Effects of a dental adhesive incorporating antibacterial monomer on the growth, adherence and membrane integrity of Streptococcus mutans. Journal of Dentistry. 2009;37:289–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie D, Weng Y, Guo X, Zhao J, Gregory RL, Zheng C. Preparation and evaluation of a novel glass-ionomer cement with antibacterial functions. Dental Materials. 2011;27:487–96. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonucci JM, Zeiger DN, Tang K, Lin-Gibson S, Fowler BO, Lin NJ. Synthesis and characterization of dimethacrylates containing quaternary ammonium functionalities for dental applications. Dental Materials. 2012;28:219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imazato S, Kinomoto Y, Tarumi H, Ebisu S, Tay FR. Antibacterial activity and bonding characteristics of an adhesive resin containing antibacterial monomer MDPB. Dental Materials. 2003;19:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imazato S, Tay FR, Kaneshiro AV, Takahashi Y, Ebisu S. An in vivo evaluation of bonding ability of comprehensive antibacterial adhesive system incorporating MDPB. Dental Materials. 2007;23:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng L, Weir MD, Xu HH, Antonucci JM, Kraigsley AM, Lin NJ, et al. Antibacterial amorphous calcium phosphate nanocomposites with a quaternary ammonium dimethacrylate and silver nanoparticles. Dental Materials. 2012;28:561–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng L, Zhang K, Melo MA, Weir MD, Zhou X, Xu HH. Anti-biofilm dentin primer with quaternary ammonium and silver nanoparticles. Journal of Dental Research. 2012;91:598–604. doi: 10.1177/0022034512444128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu X, Wang Y, Liao S, Wen ZT, Fan Y. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial dental monomers and composites. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B Applied Biomaterials. 2012;100:1151–62. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weng Y, Howard L, Guo X, Chong VJ, Gregory RL, Xie D. A novel antibacterial resin composite for improved dental restoratives. Journal of Materials Science. 2012;23:1553–61. doi: 10.1007/s10856-012-4629-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Landuyt KL, Snauwaert J, De Munck J, Peumans M, Yoshida Y, Poitevin A, et al. Systematic review of the chemical composition of contemporary dental adhesives. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3757–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imazato S, Kuramoto A, Takahashi Y, Ebisu S, Peters MC. In vitro antibacterial effects of the dentin primer of Clearfil Protect Bond. Dental Materials. 2006;22:527–32. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li F, Chai ZG, Sun MN, Wang F, Ma S, Zhang L, et al. Anti-biofilm effect of dental adhesive with cationic monomer. Journal of Dental Research. 2009;88:372–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034509334499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beyth N, Yudovin-Farber I, Bahir R, Domb AJ, Weiss EI. Antibacterial activity of dental composites containing quaternary ammonium polyethylenimine nanoparticles against Streptococcus mutans. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3995–4002. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang K, Melo MA, Cheng L, Weir MD, Bai Y, Xu HH. Effect of quaternary ammonium and silver nanoparticle-containing adhesives on dentin bond strength and dental plaque microcosm biofilms. Dental Materials. 2012;28:842–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng L, Weir MD, Zhang K, Arola DD, Zhou XD, Xu HHK. Dental primer and adhesive containing a new antibacterial quaternary ammonium monomer dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate. Journal of Dentistry. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.01.004. submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng YJ, Zeiger DN, Howarter JA, Zhang X, Lin NJ, Antonucci JM, et al. In situ formation of silver nanoparticles in photocrosslinking polymers. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B Applied Biomaterials. 2011;97:124–31. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu HH, Moreau JL, Sun L, Chow LC. Nanocomposite containing amorphous calcium phosphate nanoparticles for caries inhibition. Dental Materials. 2011;27:762–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weir MD, Chow LC, Xu HHK. Remineralization of demineralized enamel via calcium phosphate nanocomposite. Journal of Dental Research. 2012;91:979–84. doi: 10.1177/0022034512458288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melo MAS, Weir MD, Rodrigues LKA, Xu HHK. Novel calcium phosphate nanocomposite with caries-inhibition in a human in situ model. Dental Materials. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.10.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melo MAS, Cheng L, Zhang K, Weir MD, Rodrigues LKA, Xu HHK. Novel dental adhesives containing nanoparticles of silver and amorphous calcium phosphate. Dental Materials. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.10.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antonucci JM, O’Donnell JN, Schumacher GE, Skrtic D. Amorphous calcium phosphate composites and their effect on composite–adhesive–dentin bonding. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology. 2009;23:1133–47. doi: 10.1163/156856109x432767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Meerbeek B, Yoshida Y, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G, Duke ES, Eick JD, et al. A TEM study of two water-based adhesive systems bonded to dry and wet dentin. Journal of Dental Research. 1998;77:50–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McBain AJ. In vitro biofilm models: an overview. Advances in Applied Microbiology. 2009;69:99–132. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)69004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McBain AJ, Sissons C, Ledder RG, Sreenivasan PK, De Vizio W, Gilbert P. Development and characterization of a simple perfused oral microcosm. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2005;98:624–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shewmaker PL, Gertz RE, Jr, Kim CY, de Fijter S, DiOrio M, Moore MR, et al. Streptococcus salivarius meningitis case strain traced to oral flora of anesthesiologist. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48:2589–91. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00426-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lima JP, Sampaio de Melo MA, Borges FM, Teixeira AH, Steiner-Oliveira C, Nobre Dos Santos M, et al. Evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of photodynamic antimicrobial therapy in an in situ model of dentine caries. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2009;117:568–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Namba N, Yoshida Y, Nagaoka N, Takashima S, Matsuura-Yoshimoto K, Maeda H, et al. Antibacterial effect of bactericide immobilized in resin matrix. Dental Materials. 2009;25:424–30. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burrow MF, Tyas MJ. Clinical evaluation of three adhesive systems for the restoration of non-carious cervical lesions. Operative Dentistry. 2007;32:11–5. doi: 10.2341/06-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manuja N, Agpal NR, Pandit IK. Dental adhesion: mechanism, techniques and durability. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2012;36:223–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kitasako Y, Burrow MF, Katahira N, Nikaido T, Tagami J. Shear bond strengths of three resin cements to dentine over 3 years in vitro. Journal of Dentistry. 2001;29:139–44. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Munck J, Van Landuyt K, Peumans M, Poitevin A, Lambrechts P, Braem M, et al. A critical review of the durability of adhesion to tooth tissue: methods and results. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:118–32. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koshiro K, Inoue S, Sano H, De Munck J, Van Meerbeek B. In vivo degradation of resin–dentin bonds produced by a self-etch and an etch-and-rinse adhesive. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2005;113:341–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sideridou I, Tserki V, Papanastasiou G. Study of water sorption, solubility and modulus of elasticity of light-cured dimethacrylate-based dental resins. Biomaterials. 2003;24:655–65. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y, Spencer P. Hybridization efficiency of the adhesive/dentin interface with wet bonding. Journal of Dental Research. 2003;82:141–5. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishitani Y, Yoshiyama M, Wadgaonkar B, Breschi L, Mannello F, Mazzoni A, et al. Activation of gelatinolytic/collagenolytic activity in dentin by self-etching adhesives. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2006;114:160–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gendron R, Grenier D, Sorsa T, Mayrand D. Inhibition of the activities of matrix metalloproteinases 2, 8, and 9 by chlorhexidine. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 1999;6:437–9. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.3.437-439.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Nato F, Carrilho M, Visintini E, Tjaderhane L, et al. Chlorhexidine stabilizes the adhesive interface: a 2-year in vitro study. Dental Materials. 2010;26:320–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.11.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osorio R, Yamauti M, Osorio E, Ruiz-Requena ME, Pashley D, Tay F, et al. Effect of dentin etching and chlorhexidine application on metalloproteinase-mediated collagen degradation. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2011;119:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Agee KA, Uchiyama T, Imazato S, Mutluay MM, Cadenaro M, et al. The inhibitory effects of quaternary ammonium methacrylates on soluble and matrix-bound MMPs. Journal of Dental Research. 2011;90:535–40. doi: 10.1177/0022034510389472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donmez N, Belli S, Pashley DH, Tay FR. Ultrastructural correlates of in vivo/in vitro bond degradation in self-etch adhesives. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:355–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lynch CD, Frazier KB, McConnell RJ, Blum IR, Wilson NH. Minimally invasive management of dental caries: contemporary teaching of posterior resin-based composite placement in U.S. and Canadian dental schools. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2011;142:612–20. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loguercio AD, Reis A, Bortoli G, Patzlaft R, Kenshima S, Rodrigues Filho LE, et al. Influence of adhesive systems on interfacial dentin gap formation in vitro. Operative Dentistry. 2006;31:431–41. doi: 10.2341/05-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Damm C, Munsted H, Rosch A. Long-term antimicrobial polyamide 6/silver nanocomposites. Journal of Materials Science. 2007;42:6067–73. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rai M, Yadav A, Gade A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnology Advances. 2009;27:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Percival SL, Bowler PG, Russell D. Bacterial resistance to silver in wound care. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2005;60:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fan C, Chu L, Rawls HR, Norling BK, Cardenas HL, Whang K. Development of an antimicrobial resin – a pilot study. Dental Materials. 2011;27:322–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]