Abstract

Background

The article discusses the position of elderly patients in the context of medical intervention. The phenomenon of a “greying” population has changed the attitude towards the elderly but common observations prove that the quality of geriatric care is still unsatisfactory. This is a comparative study of personality among people at different ages, designed to improve specialists’ understanding of ageing. The results are discussed in relation to the elderly patient-centered paradigm to counterbalance ageist practices.

Material/Methods

This study involved 164 persons in early and late adulthood. Among the old, there were the young old (ages 65–74) and the older old (ages 75+). All participants were asked to fill-out the NEO-FFI [11].

Results

The results demonstrate age-related differences in personality. In late adulthood, in comparison to early adulthood, there is decreased openness to new experiences. Two traits – agreeableness and conscientiousness – increase significantly. Age did not differentiate significantly the level of neuroticism or extraversion. The results of cluster analyses show differences in taxonomies of personality traits at different periods of life.

Conclusions

The results challenge the stereotypes that present older people as neurotic and aggressive. Age did not significantly influence the level of neuroticism or extraversion. In general, the obtained results prove that the ageist assumption that geriatric patients are troublesome is false. This article builds support for effective change in geriatric professional practices and improvement in elderly patients’ quality of life.

Keywords: aging, coping strategies, prophylaxis of aging, the satisfaction with one’s own activity

Background

Demands for care services are growing as the ageing population becomes an obvious phenomenon [1]. Nowadays, one witnesses the highest participation of seniors in modern societies in history. In Europe, the problem of the growing “grey” population is overwhelming. Joyce and Loe [2] searched worldwide for countries with the highest proportion of citizens over 65. Of the 25 leading “grey” countries, 23 were in Europe. Demographic forecasts estimate that 20% of the U.S. population will be over age 65 by 2030; in Canada, this level is to be attained in 2024 [2]. In China, where there are currently about 120 million people over 60 years old, the number will double by 2030 [3].

As the number of seniors increases, the number of patients increases due to advances in medicine that prolong the life expectancy of seniors with medical conditions. Bigby [4] analyzed ageing among people with intellectual disabilities. During the period of 1900 to 1930, these people only lived to an average age of 20 years; but by 1993, they survived on average to age 70. This demonstrates that the ageing process poses new challenges, not only for the old themselves, but also for their families, doctors, therapists, and the whole health care system [4,5]. The decrease in informal care by family members is becoming more common [3,6,7] and the percentage of elderly who live alone is also increasing. All in all geriatric complex healthcare services become a dynamically growing demand [4,7,8].

Lifespan psychologists currently agree that ageing should not be perceived only as a decline, but also as a further stage of individual growth. But many medical practitioners know little about geriatric patients [7]. Their expectations are deeply rooted in cultural stereotypes and prejudices. Their personal view of ageing leads to an inadequate, negative, and mechanistic approach to elderly patients. Many practitioners still consider old patients as untreatable or presenting hostility and anger. Thus, they expect a high workload and stress of different occupations working in the geriatric care sector. These factors, plus a lack of financial resources, are why so few physicians, nurses, and other employees in professional care decide to specialize in geriatric branches of medicine [6].

The purpose of this paper is to stress the urgent need for improvement of medical and social care for the elderly. To enhance the incentive for a higher quality of service, there should be a visible change in specialists’ approach to ageing. This is because one of the remaining barriers to improvements in geriatric care is the lack of adequate knowledge about late adulthood. Changing these factors may result in the improvement of specialists’ attitude towards the elderly. This can address the demand for quick and cost-limited solutions in order to bring long-term gains for patients and caregivers. To provide appropriate interventions, it is necessary to understand what constitutes good quality of life for the elderly. The first step to achieve this goal is to investigate how people grow older. This paper discusses the results of measurement of personality in 2 age-groups: early and late adulthood.

Personality Variation in Late Adulthood

The study of development of personality in adulthood has been widely discussed in the literature [1,9]. In general it is assumed that in old age personality changes, mostly due to cognitive decline. However, the influence of the individual’s social environment on personality traits can be also very significant as well as life history. This approach is developed mostly by the contextualists [9]. According to a transactional perspective on mean-level personality changes, the different normative experiences lead to the advancement of personality growth. In late adulthood, for example, there are some important social role domains that undergo changes; these are connected with an urgent need to redefine personal identity after retirement [1], with grand-parenting children and some volunteering [10], and with the feeling of loss that accompany the deaths of relatives and intimate friends. The current literature provides some hints about how personality traits change. It is predicted that agreeableness, which is linked to prosocial behaviors [9], should undergo changes, as well as conscientiousness linked to work commitment [9]. Moreover other theories suggest that as people grow older they become more mature at emotional regulation [1,9]. This should lead to decline in neuroticism with age. According to socioemotional selectivity theory, the levels of openness and extraversion decline, and agreeableness increases [9]. These changes are provoked mostly by the social marginalization of the old. Knowledge about how personality traits change across the life span may help physicians and other healthcare providers in offering more effective services. This process must take consecutive steps: changing their viewpoints, altering their attitudes towards the old, and replacing ageist practices with positive behaviors.

Material and Methods

The present study was designed to test a hypothesis about adult personality changes during different developmental stages. The sample included 164 subjects aged 19–92 years who were all research volunteers recruited through word of mouth. Personality data were available for 108 women (66%) and 56 men (34%). The detailed information on age is presented in Table 1. Late adulthood was divided into 2 subgroups – young, old, and older old – to study the differences of less and more advanced age.

Table 1.

The mean age of participants during studied life periods.

| Variable | Mean age in years (SD) | Variable | Mean age in years (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early adulthood (N=82) | 22.99 (2.47) | Men (N=28) | 23.46 (2.92) |

| Women (N=54) | 22.74 (2.47) | ||

| Late adulthood (N=82) | 73.16 (6.5) | Men (N=28) | 72.29 (5.47) |

| Women (N=54) | 73.6 (6.99) | ||

| Young old (N=41) | 67.46 (2.24) | Men (N=14) | 67.21 (1.42) |

| Women (N=27) | 67.59 (2.58) | ||

| Older old (N=41) | 78.85 (3.79) | Men (N=14) | 77.36 (2.17) |

| Women (N=27) | 79.63 (4.23) |

To measure the Big Five personality dimensions, all participants filled out the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) [11]. The NEO-FFI items are short and easy-to-understand phrases to assess neuroticism, extraversion, openness to new experiences, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. The psychometric properties and measuring qualities of the inventory have been investigated and approved. The NEO-FFI items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 – disagree strongly to 5 – agree strongly[11]. The study was carried out in a paper and pencil format. Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics, comparison of mean scale values using analysis of variance, and cluster analysis.

Results

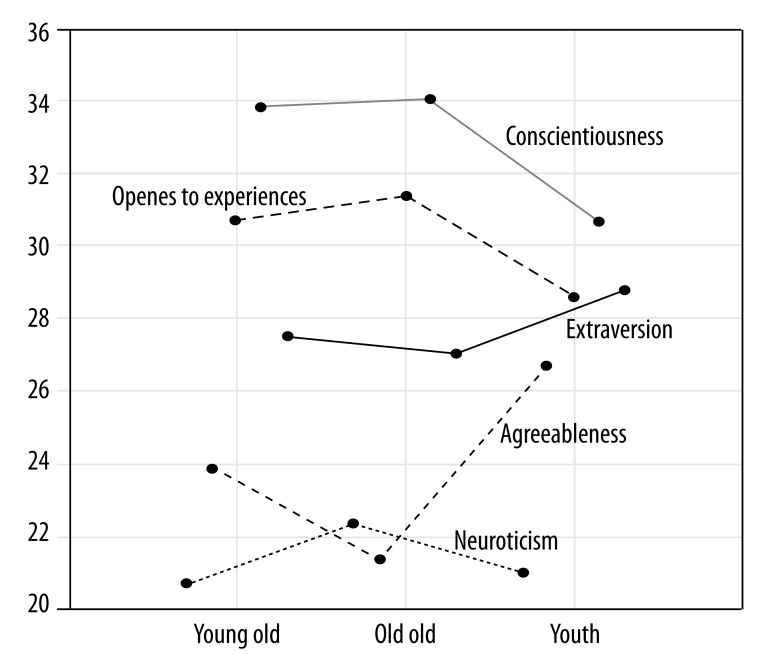

For purposes of statistical analysis we compared the results received into 3 age groups: early adulthood, the young old, and the older old. The obtained differences among the mean scores are in accordance with studies of mean-level change in the Big Five [9]. The trends are stable: conscientiousness and agreeableness tend to increase with age, but extraversion does not change significantly. The basic pattern of neuroticism decline is found in the young old period. Later in life, the results tend to increase (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Mean scores and standard deviations (SD) of personality traits.

| Variable | Total sample (N=164) Mean (SD) | Men (N=56) Mean (SD) | Women (N=108) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | 21.62 (8.26) | 19.96 (8.59) | 22.48 (7.98) |

| Extraversion | 28.09 (6.49) | 27.91 (6.42) | 28.19 (6.55) |

| Openness to experiences | 24.44 (7.31) | 25.21 (7.43) | 24.04 (7.25) |

| Agreeableness | 30.36 (6.32) | 28.13 (5.97) | 31.52 (6.21) |

| Conscientiousness | 32.80 (6.49) | 30.84 (7.81) | 33.81 (6.56) |

| Age groups | Early adulthood (N=82) Mean (SD) | Young old (N=41) Mean (SD) | Old old (N=41) Mean (SD) |

| Neuroticism | 21.34 (8.18) | 21.07 (7.77) | 22.73 (8.96) |

| Extraversion | 28.85 (6.31) | 27.59 (6.52) | 27.07 (6.76) |

| Openness to experiences | 26.50 (6.86) | 23.63 (7.84) | 21.12 (6.34) |

| Agreeableness | 29.13 (5.98) | 31.24 (6.03) | 31.93 (6.90) |

| Conscientiousness | 31.13 (7.68) | 34.37 (6.43) | 34.56 (5.90) |

Figure 1.

Differences in means scores of personality traits.

To evaluate the significance of the obtained differences of the mean scores, we ran analysis of variance. A significant group effect was found for 3 traits: openness to new experiences, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. The differences among the means of neuroticism and extraversion in the 3 analyzed groups were not significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of analysis of variance in three age subgroups.

| Variable | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | 0.505 | 0.604 |

| Extraversion | 1.199 | 0.304 |

| Openness to experiences | 8.440 | 0.001 |

| Agreeableness | 3.293 | 0.039 |

| Conscientiousness | 4.682 | 0.010 |

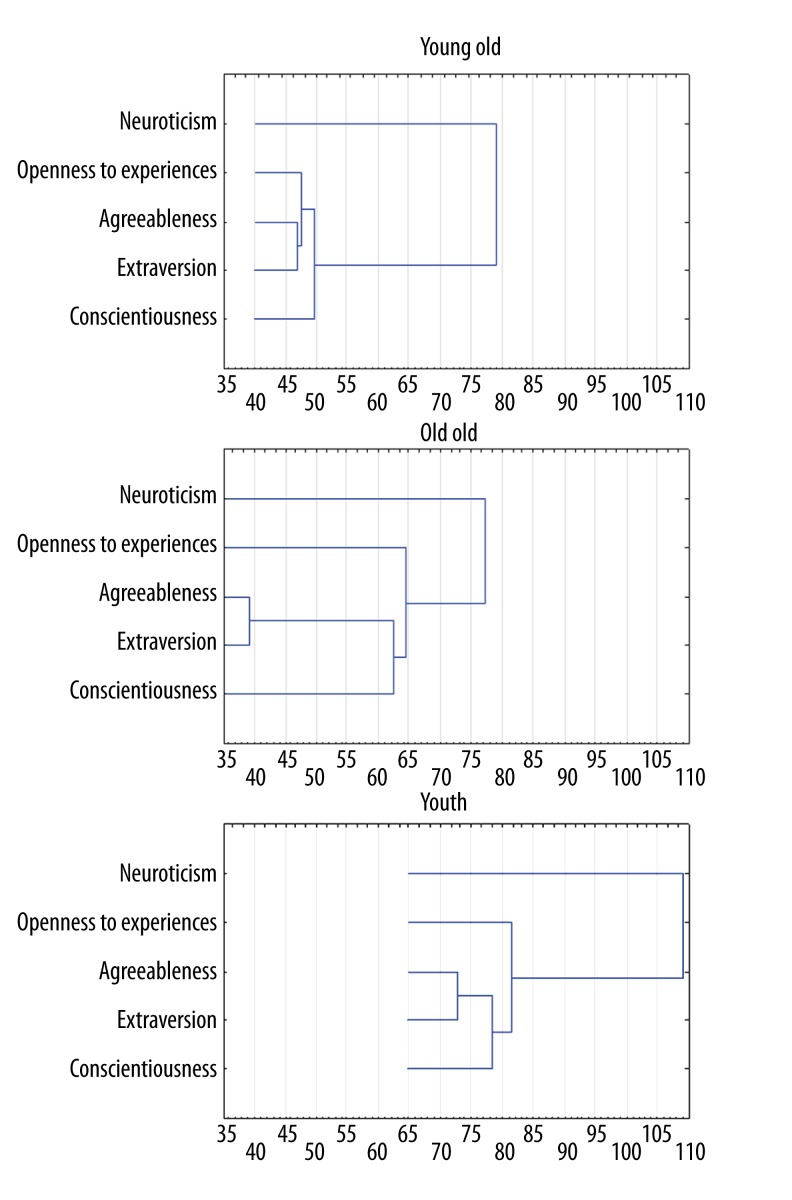

Cluster analyses were performed to test for more descriptive change patterns. The data showed some interesting age effects. The clustering techniques showed some differences in taxonomies of personality traits. In general, a horizontal hierarchical tree plot proved that the patterns according to which the traits aggregate in youth and young old groups are quite similar.

In both subsamples, neuroticism showed the strongest uniqueness of all traits. Although in the old old this tendency was also found, the distance between neuroticism and the other aggregated traits was smaller. Analyzing the similarities among traits in 2 age groups (youth and young old), the most similar ones were agreeableness and extraversion. In the old old group, the first cluster was composed of agreeableness and conscientiousness (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The results of cluster analyses in three age subgroups.

Discussion

Geriatric patients are a heterogeneous population. They differ not only in socioeconomic and educational status, but also in personality. Nevertheless, there is a common practise of the specialists and the general public to focus on such topics as Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, chronic rheumatology, muscle impairment, cerebrovascular disease, and functional decline. This practice does not reveal the true quality of aging and illustrates Gergen and Gergen’s statement that “the geriatric set” has a negative attitude towards the ageing population. To improve this situation, a good understanding of the patient is needed, including proper recognition of personality differences and life span dynamics. This knowledge is a key component of openness to the elderly in the context of geriatric care. In this article, the relation between age and personality traits in early and late adulthood was examined. The main aim was to determine if the “soft plaster effect” [9] supports prejudices towards misbehaviors of geriatric patients. Although some changes in personality traits were demonstrated, none of them supported maladaptive changes in behaviors that develop as ageing progresses. The data did not show the expected personal deterioration and reduction in social abilities of the old compared to young adults. The differences in the measurement of the personality traits of the old do not manifest any clear impairments or functional declines in comparison to the young. On the contrary, the observed changes – a significant increase in conscientiousness and agreeableness – may indicate better social adaptation as people get older. As Coleman [14] points out, a slightly higher score in neuroticism and high score in conscientiousness can be implicated in health-promoting behavior: to trace symptoms, to seek medical advice for early signs of illness, and to faster physical recovery.

What do the results discussed in this article imply for improvement in geriatric medical practices? The results of study of the ageing process need to be disseminated to healthcare providers and may lead to comprehensive care for older persons and to general improvements in their quality of life. Re-education and change among professionals in geriatric knowledge and skills, as well as expectations and perceptions of the elderly’s needs, will decrease costs of medical interventions and increase effectiveness in formulating, executing, and evaluating appropriate services in the elder care sector.

Personality data from our study show that patterns of change in traits are determined not solely by biological evolution, but also by culture and social interactions. If we agree that adult personality is characterized by plasticity, we realize that manipulation of life context will contribute to the mechanism of personality change. This knowledge may help in improving attitudes, and thus improving quality of relationships between geriatric patients and their physicians. This attempt to re-educate and sensitize healthcare workers to have positive attitudes toward ageing should be made at least at the individual level of geriatric professionals and also among healthcare teams and organizations providing healthcare. It demands development of new strategies of medical practices that encourage the physicians to increase knowledge-to-action and positive attitude towards the old, and to exchange experiences with coworkers in order to develop expertise in geriatrics and master the competence necessary for successful interventions with geriatric patients. Although professionals should receive geriatric training to master skills in caring for the elderly’s unique needs, they should also learn that personality of geriatric patients is not destined for psychopathology or any other social deviation. Educating professionals providing services geriatrics and gerontology will improve the quality of life of the elderly.

Health care and the quality of life

The old are the marginalized and often ignored. The first step to change this is to convince the healthcare providers to revise their beliefs about geriatric patients’ personalities. Using the results of the present study, they should learn that there is no specific age-determined pathology in personality traits taxonomy. This novel insight into the nature of ageing may stimulate some changes in their professional practices and thus improve the quality of life of the elderly patients. This is because the main issue in healthcare situations concerns the problem of balance between extending life and assuring that this life remains worth living [12].

The pitfalls of thinking about geriatric patients and their position lead to serious misunderstandings and lack of care. Examples of disregard for elderly patients among medical staff are common and include frequent misdiagnosis, ignorance of important symptoms, and communication barriers [8]. This situation resembles a self-perpetuating cycle of despair and resignation.

The last few years have seen a considerable amount of research and publications on the issues of the greying population. Thus, we may admit that the position of an average elderly patient does not resemble that described in sophisticated models of “geroscience”. Although we should be critical of some overgeneralizations, we should also agree on common practices. If we take into account the characteristics of quality of life (QoL) of the old, we come up with some general conclusions:

Life satisfaction is not merely an idea in gerontology literature, but this is a shared experience among the old [8];

Health determinants are important aspects of life satisfactions in late adulthood;

Objective handicap judged by the professionals differs from subjective handicap perceived by the patient [13];

Social expectations and cultural environment are important elements of the elderly’s feeling of being handicapped.

The last problem is the most important to be recognized and discussed further in detail. Social environment, attitudes, stereotypes, and prejudices play a central role in modelling the elderly’s concept of being a patient and in defining the range of responsibility and possible tasks for the patient. Unfortunately, the elderly are most often thought to adapt to being handicapped. In social perception, the old fit the “handicap profile” well. In the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps (ICIDH), a handicapped person is one whose ability to survive is limited in at least one of the following areas: 1) orientation, 2) physical independence, 3) mobility, 4) occupations, 5) social integration, 6) economic independence, and 8) other domains [13]. Most of the listed domains of handicap are prescribed to the elderly people and also relate to their quality of life [13]. Gaillard et al. [15] proved empirically that older adults exposed to age-related stereotypical expectations had worse performance. In other words, the elderly’s self-regulatory mechanisms are prone to stereotype threat effects. Furthermore, they influence the elderly’s well-being. This is only one example of numerous external forces impinging on the elderly’s self-esteem and QoL (see: double/triple jeopardy [1], internalized ageism [16]). The impact of possible significant shifts in specialists’ attitudes to ageing and to older adults is almost certain to improve the quality of lives of future cohorts of older patients. If healthcare providers approach older people with adequate knowledge and an open mind, the future generations of the elderly, as Stuart-Hamilton states, will stand up for what they want, rather then what younger adults are foisting on them ‘for their own good’ [1].

There are many possible predictors of personality (e.g., genes, cultural and social contexts, and individual experiences. Among all of them, there is also an evident age effect. In this article we attempted to sensitize the healthcare workers and raise their awareness about the quality of personality changes in late adulthood. The presented data proves that the ageist view on geriatric patients is a serious misjudgment and the starting point to search for solutions to improve the standards of caring for the elderly that will be positively evaluated from both receivers’ and providers’ points of view. This is important in the geriatric patients’ current situation when many medical services and devices are inaccessible and too expensive. The irregular and insufficient utilization of healthcare services is also due to their poverty, immobility, misconceptions, and misinformation of the necessity of constant compliance with treatment plans and drug regimens. Thus, it is impossible to overstate the importance of any attempts to improve the quality of geriatric care.

A proper attitude toward geriatric patients helps physicians, therapists, and caregivers to provide adequate care at a lower cost and delay admission into high-cost institutional care. It leads to using home-care in place of geriatric and hospice care. But to achieve it, physicians must demonstrate better recognition of the clinical, functional, and individual implications of ageing. They should also become more reliable and trustworthy in the elderly’s view. The improvement of elder care lowers psychological burdens of patients. The safe and nurturing environment created by specialists, patients, and their relatives cooperating together provides numerous benefits such as higher emotional and social support for patients’, better health outcomes for patients, and lesser damage to the health of caregivers. This paper argues that we can enhance the probability of success through the education and training of healthcare providers and then disseminating the evidence for improvements through the knowledge-to-action cycle.

The interest in personality has many meaningful outcomes in the fields of diagnosis and therapy [14]. Physicians as well as therapists and caregivers must learn how to use the knowledge of personality traits in better understanding the progress of a disease. It is good to know that patients with different personalities may manifest the symptoms of diseases with different indicators at different points in time. Furthermore, physicians and healthcare providers should also be aware of the fact that patients with different personalities may be prone either to health-damaging behaviors or health-promoting actions. Depending on their personality traits, patients are more or less open to change, more or less motivated to recovery from illness, and prefer and choose different strategies for coping with acute and chronic illness. It improves the satisfaction with one’s own activity, even in conditions of limitations, which allows for some degree of recompense for the impact of ageing on the functioning of the elderly person, which is important for quality of life [17–19]. All these facts prove how useful personality diagnosis may be for improvement of medical and social care for the elderly.

Conclusions

The results challenge the stereotypes that present older people as neurotic and aggressive. Age did not significantly correlate with the level of neuroticism and extraversion. In general, the obtained results prove that the ageist assumption that geriatric patients are troublesome is false. This article builds support for effective change in geriatric professional practices and improvement in the elderly patients’ quality of life.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Stuart-Hamilton I. The psychology of ageing. London & Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joyce K, Loe M. Theorising technogenarians: a sociological approach to ageing, technology and health. In: Joyce K, Loe M, editors. Technogenarians Studying health and illness through an ageing, science, and technology lens. Wiley-Black; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie X, Xia Y, Liu X. Family income and attitudes toward older people in China: comparison of two age cohort. JFEI. 2007;28(1):171–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigby Ch. Ageing with a lifelong disability A guide to practice, program and policy issues for human services professionals. London & Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moye J, Armesto JC, Karel MJ. Evaluating capacity of older adults in rehabilitation settings: conceptual models and clinical challenges. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2005;50(3):207–14. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nübling M, Vomstein M, Schmidt SG, et al. Psychosocial work load and stress in the geriatric care. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:428. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans JM, Kiran PR, Bhattacharyya OK. Activating the knowledge-to-action cycle for geriatric care in India. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Błachnio A. Impact of older adults’ social status and their life satisfaction on health care resources. Acta Neuropsychologica. 2011;9(4):335–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srivastava S, John OP, Gosling SD, Potter J. Development of personality in early and middle adulthood: set like plaster or persistent change? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(50):1041–53. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Błachnio A, Starostecka JE. Volunteering activity in late adulthood. Motives and personality conditioning. In: Liberska H, editor. Current psychosocial problems. Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zawadzki B, Strelau J, Szczepaniak P, Œliwińska M. Adaptacja polska. Podręcznik. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP; 1998. Inwentarz osobowości NEO-FFI Costy i McCrae. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pąchalska M, Buliński L, Makarowski R. Izolacja społeczna osób po urazie mózgu. In: Rostowska T, Peplińska A, editors. Psychospołeczne aspekty życia rodzinnego. Warszawa: Dyfin; 2010. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein Hofmeijer MAJ. Long term handicap after traumatic brain injury: its relationship to quality of life. Acta Neuropsychologica. 2005;3(1/2):2–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman PG. Personality, health and ageing. J R Soc Med. 1997;90(Suppl 32):27–33. doi: 10.1177/014107689709032s08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaillard M, Desmette D, Keller J. Regulatory focus moderates the influence of age-related stereotypic expectancies on older adults’ test performance and threat-based concerns. J Revue européenne de psychologie appliquée. 2011;61:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett AE, Cantwell LE. Drawing on stereotypes: using undergraduates’ sketches of elders as a teaching tool. Educational Gerontology. 2007;33:327–48. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pąchalska M, Mańko G, Chantsoulis M, et al. The quality of life of persons with TBI in the process of a Comprehensive Rehabilitation Program. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(13):CR432–42. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomaszewski W, Mańko G, Pachalska M, et al. Improvement of the Quality of Life of the persons with degenerative joint disease in the process of a comprehensive rehabilitation program enhanced by Tai Chi: the perspective of increasing therapeutic and rehabilitative effects through the applying of eastern techniques combining health-enhancing exercises and martial arts. Arch Budo. 2012;7(3):169–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomaszewski W, Mańko G, Ziółkowski A, Pąchalska M. An evaluation of health-related quality of life of patients aroused from prolonged coma when treated by physiotherapists with or without training in the ‘Academy of Life’ programme. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2013;20(2):319–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]