Abstract

Replication-competent, attenuated herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) derivatives that contain engineered mutations into the viral γ34.5 virulence gene have been used as oncolytic agents. However, as attenuated mutants often grow poorly, they may not completely destroy some tumors and surviving cancer cells simply regrow. Thus, although HSV-1 γ34.5 mutants can reduce the growth of human tumor xenografts in mice and have passed phase I safety studies, their efficacy is limited because they replicate poorly in many human tumor cells. Previously, we selected for a γ34.5 deletion mutant variant that regained the ability to replicate efficiently in tumor cells. Although this virus contains an extragenic suppressor mutation that confers enhanced growth in tumor cells, it remains attenuated. Here, we demonstrate that the suppressor virus replicates to greater levels in prostate carcinoma cells and, importantly, is a more potent inhibitor of tumor growth in an animal model of human prostate cancer than the γ34.5 parent virus. Thus, genetic selection in cancer cells can be used as a tool to enhance the antitumor activity of a replication-competent virus. The increased therapeutic potency of this oncolytic virus may be useful in the treatment of a wide variety of cancers.

Throughout the past century, there have been sporadic reports of malignancies regressing in response to coincidental infections (reviewed in ref. 1). These reports are supported, in principle, by the observation that viral infections can regress experimentally induced tumors in animal models of human cancer (2–4). To implement a biological agent as a potential therapeutic agent in the treatment of human cancer, however, requires that its ability to cause disease be effectively curtailed. The advent of genetic engineering techniques has made it possible to selectively ablate viral virulence genes in the hope of creating a safe, avirulent virus that can selectively replicate in and destroy tumor cells (2–4). Such a virus would be able to propagate an infection throughout a tumor mass and directly kill the cancer cells, but be unable to inflict substantial damage to normal terminal differentiated cells. Although safe viruses have been created by such methodology, the attenuation process often has an overall deleterious effect on viral replication. This replication defect prevents the virus from completely destroying the tumor mass, and the surviving cancer cells can simply regrow. Thus, enhancing the ability of weakened, attenuated mutants to grow in cancer cells without a concomitant increase in their toxicity to normal tissues could have an enormous impact on the effectiveness with which a replication-competent virus destroys a tumor.

The antitumor potential of replication-competent herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) with engineered mutations in the γ34.5 virulence gene has been explored in several studies (refs. 5–8; reviewed in refs. 3 and 4). HSV-1 is a neurotrophic herpes virus, and its ability to replicate and cause disease in the central nervous system is governed by multiple viral gene products (reviewed in ref. 9). The γ34.5 gene is a critical determinant of viral neurovirulence, because γ34.5 mutants are effectively non-neurovirulent in mice and monkeys (6, 10–12). Recently, two different γ34.5 mutant derivatives successfully completed phase I safety studies where they were inoculated intracranially into human subjects (13, 14). Although γ34.5 mutant derivatives can suppress the growth of xenografts in animal models of human cancer, their overall effectiveness as an antitumor agent is diminished by their impaired ability to replicate in some human tumor cells.

γ34.5 mutants cannot complete their lytic program in many tumor cells because of the activation of a cellular antiviral response that inhibits protein synthesis. The γ34.5 gene product encodes a regulatory component for the protein phosphatase 1α catalytic subunit that is required to maintain pools of active, unphosphorylated eIF2, a critical translation initiation factor (15). In the absence of the γ34.5 protein, the cellular PKR kinase is activated, phosphorylated eIF2 accumulates, and the initiation of protein synthesis is blocked (16, 17). The inhibition of translation severely impairs viral growth. To create a γ34.5 mutant with increased capacity to replicate in and kill cancer cells, we performed a genetic selection that capitalized on the poor growth of γ34.5 mutants in tumor cells. Following the serial passage of a γ34.5 deletion mutant in cultured human tumor cells, we isolated a suppressor variant that contained a novel mutation and exhibited dramatically improved growth properties (18). This extragenic suppressor virus contains an additional mutation that overcomes the protein synthesis block by altering the temporal expression profile of Us11, a viral RNA-binding protein, from late in the infectious program to very early in the cycle (18–20). Accumulation of Us11 at early times inhibits the activation of the cellular PKR kinase and allows protein synthesis to proceed in the absence of the γ34.5 gene product (19, 21). Thus, the suppressor virus is more effective at killing tumor cells because it prevents a cellular antiviral response that inhibits protein synthesis. Surprisingly, although the suppressor regained the ability to replicate in tumor cells that failed to support the replication of the γ34.5 parent virus, it remained severely attenuated for neurovirulence following intracerebral injection into immunocompetent mice and i.p. administration to athymic mice. Subsequent analysis demonstrated that the attenuated phenotype of the suppressor virus in mice is completely due to the γ34.5 mutation (22). Here, we report that the suppressor virus replicates to greater levels than the γ34.5 parent virus in prostate carcinoma cells and is a more effective antineoplastic agent in an animal model of human cancer. This demonstrates that the introduction of additional mutations into the viral genome can dramatically improve the ability of replication-competent viruses to destroy tumors in vivo without a corresponding increase in virulence. Furthermore, it has implications for the design of future, more efficacious viral antitumor agents.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Viruses.

PC3 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were propagated in Ham's F-12 media (GIBCO) supplemented with 5% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO). The HSV-1 Patton strain is used exclusively in this study. All viral nucleotide numbers refer to the published coordinates for the sequenced strain 17 (GenBank accession no. X14112). In the Δ34.5 virus, both copies of the γ34.5 gene have been replaced with sequences that encode β-glucuronidase. The suppressor (SUP) virus used in these studies was isolated at New York University School of Medicine and is identical to the SUP1 isolate described previously (18). In addition to the γ34.5 deletion present in the Δ34.5 virus, the SUP virus contains a deletion of nucleotides 145416–145999. This mutation removes the endogenous Us11 late promoter, and allows Us11 to be expressed from the Us12 immediate early promoter (19).

Analysis of Viral Protein Synthesis.

High multiplicity infections and metabolic labeling of infected cells was performed as described (18).

Establishment and Treatment of Subcutaneous PC3 Tumors in Mice.

1 × 108 PC3 cells were injected s.c. into the flank of a BALB/c nu/nu outbred mouse (Charles River Breeding Laboratories). Tumors were measured every other day with Vernier calipers and their volume was determined by using the formula 0.52 × width × height × depth. Once the tumor size reached 150 mm3, the animal was killed and the tumor was explanted and sectioned into fragments that measured 2 × 2 × 2 mm. Individual fragments were implanted s.c. into tumor naive mice. When the transplanted tumors reached a size of ≈50 mm3, groups of five mice received a single injection of virus or a virus-free lysate prepared from mock-infected cells. Tumors were measured every 2 days for 34 days, at which point the animals were killed and tumors were harvested, weighed, and frozen for subsequent histological studies. P values were calculated by direct comparison of tumor volumes in different treatment groups on completion of the study by using an ANOVA t test (JMP software package, SAS Institute, Cary, NC)

Histology.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of frozen tissue sections was performed by using standard methodology. To detect β-glucuronidase by in situ staining, frozen tissue sections were fixed in 1.25% glutaraldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. The sections were washed in PBS and then submerged in 1 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-D-glucuronide for 4 h at 37°C. After the substrate was washed away, nuclear fast red was applied as a counterstain for 5 min at room temperature. Sections were then mounted with Crystal/Mount before inspection.

Results

Replication of the Suppressor Mutant in Prostate Cancer Cells.

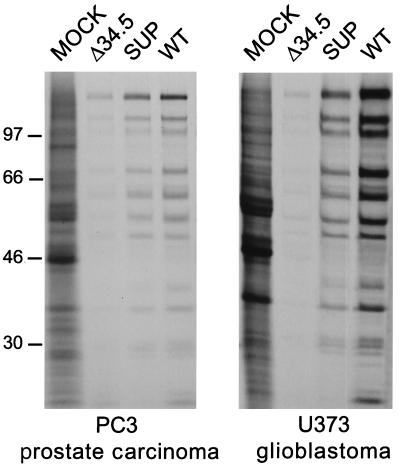

To explore the effectiveness of the suppressor mutant as an antitumor agent, we chose to focus our attention on an animal model of human prostate cancer. As the suppressor virus was initially selected for its enhanced ability to replicate in human glioblastoma cells, it was necessary to examine its ability to replicate in prostate carcinoma cells. Replicate dishes of PC3 human prostate carcinoma cells were either mock infected, or infected at high multiplicity with the γ34.5 deletion mutant (Δ34.5), the extragenic suppressor (SUP), or wild-type HSV-1. At late times postinfection, the cultures were labeled with 35S amino acids, and cell-free lysates were prepared and fractionated by gel electrophoresis. Fig. 1 demonstrates that the suppressor virus directs greater levels of viral protein synthesis than the Δ34.5 parent virus in PC3 cells, and the phenotype is similar to that observed previously in U373 glioblastoma cells. In both cell types, the suppressor virus directs near wild-type levels of protein synthesis. The suppressor virus is more effective at killing tumor cells because it can prevent a cellular antiviral response that inhibits protein synthesis. HSV-1 γ34.5 mutants cannot inhibit this response, limiting their growth in many cell types. In the absence of the γ34.5 protein, the initiation of protein synthesis is blocked late in infection, and the production of viral proteins required to assemble infectious progeny virions is prevented, severely limiting viral growth (16, 17). The additional mutation present in the suppressor virus allows for the expression of the Us11 viral RNA binding protein early in the infectious cycle and this prevents the premature cessation of protein synthesis (19). A comparable phenotype to that described for prostate carcinoma and glioblastoma cell lines in Fig. 1 has been observed in a variety of transformed human cell lines, including those derived from neuroblastoma, cervical carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, and embryonic kidney (ref. 17; S.M. and I.M., unpublished observation). Thus, a diverse assortment of human tumor cell lines that do not support sustained protein synthesis following infection with γ34.5 mutants allow the suppressor virus to synthesize near wild-type levels of late viral proteins and complete their replicative cycle.

Figure 1.

Examination of viral protein synthesis in prostate carcinoma and glioblastoma cells. PC3 prostate carcinoma and U373 glioblastoma cells were mock-infected, or infected at high multiplicity with either the γ34.5 deletion mutant virus (Δ34.5), the suppressor virus (SUP), or wild-type HSV-1 (WT). Following a 1-h pulse with 35S amino acids at late times postinfection, proteins were solubilized in sample buffer and fractionated by SDS/PAGE. The fixed, dried gel was subsequently exposed to Kodak XAR film. Molecular mass markers, in kilodaltons, appear on the left.

To quantitatively compare the ability of Δ34.5 and SUP viruses to replicate in tumor cells, cultures of either PC3 prostate carcinoma cells or U373 glioblastoma cells were infected at low multiplicity with either Δ34.5, SUP, or wild-type HSV-1. At 5 days postinfection, cell-free lysates were prepared and the virus produced was titered in permissive monkey kidney cells (Vero). Under these conditions, the suppressor virus replicates to 102-fold greater levels than Δ34.5 in PC-3 cells, and to 104-fold greater levels in U373 glioblastoma cells (Table 1). Thus, the enhanced growth of the suppressor virus is not limited to glioblastoma cells, but is also seen in prostate cancer cells.

Table 1.

Replication of the suppressor virus and the γ34.5 mutant virus in human cancer cells

| Virus | Titer of virus grown in PC3 cells | Titer of virus grown in U373 cells |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 1.1 × 108 | 9 × 108 |

| SUP | 3 × 107 | 8.1 × 107 |

| Δ34.5 | 2.8 × 105 | 4.3 × 103 |

PC3 or U373 (3 × 106) cells were infected with 103 pfu of either the γ34.5 deletion mutant Δ34.5, the SUP suppressor virus, or wild-type HSV-1 (WT). After 5 days, cell-free lysates were prepared and titered in permissive African Green Monkey kidney (Vero) cells.

Antitumor Activity of the Suppressor Mutant in an Animal Model of Human Prostate Cancer.

To evaluate the ability of the suppressor virus to reduce the growth of tumors in vivo, s.c. xenografts of human PC3 prostate carcinoma cells were established in immunocompromised (nude) mice. Once the implanted tumors reached ≈50 mm3 in volume, they were challenged by a single injection of either the Δ34.5 mutant virus, the SUP γ34.5 extragenic suppressor virus, or a virus-free lysate prepared from mock infected cells. Fig. 2a demonstrates that Δ34.5 can reduce the growth of PC3 xenografts at a dose of 2 × 107 plaque-forming units (pfu). This is in agreement with results obtained by other groups using different tumor cell lines and serves to validate our experimental system. The suppressor virus was more effective than Δ34.5 at reducing the growth of the PC3 xenograft at a dose of 2 × 107 pfu (Fig. 2a). Comparable results have been obtained in three independent experiments (P = 0.015, n = 18 for Δ34.5 vs. SUP at 2 × 107 pfu). At the lower doses of 2 × 106 and 2 × 105 pfu, Δ34.5 was not effective in reducing the growth of the xenograft (P > 0.5 for Δ34.5 vs. mock at 2 × 106 pfu, Fig. 2b; P > 0.25 at 2 × 105 pfu, data not shown). The SUP virus, however, was extremely effective in inhibiting the growth of the PC3 xenograft at doses of 2 × 106 and 2 × 107 pfu (Fig. 2; P < 0.05 for SUP vs. mock). Significantly, the antitumor activity of SUP at the reduced dose of 2 × 106 pfu was substantially greater than Δ34.5 (Fig. 2b; P < 0.05 for SUP vs. Δ34.5 at 2 × 106 pfu). In addition, SUP retained antitumor activity at 2 × 105 pfu, the lowest dose tested (P = 0.05 for SUP vs. mock at 2 × 105 pfu, data not shown). At all doses examined, including the lower doses of 2 × 105 and 2 × 106 pfu, the suppressor virus is more effective than the Δ34.5 parent virus at reducing the size of the xenograft by 50% or greater (Table 2). Furthermore, only groups treated with the SUP virus yielded animals that completely responded and had no measurable tumor burden by the conclusion of the study period. Thus, the enhanced replication of the SUP virus observed in cultured cells correlates with its greater oncolytic activity at reduced doses in animals. The improved growth properties of the suppressor virus may also be responsible for the larger number of animals that completely responded to treatment.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the suppressor virus as an antitumor agent in an animal model of human prostate cancer. BALB/c nu/nu mice (n = 5 for each treatment group) harboring established, s.c. PC3 tumors measuring ≈50 mm3 received a single injection containing 2 × 107 pfu (a) or 2 × 106 pfu (b) of either the γ34.5 deletion mutant Δ34.5 (▴, broken line), the suppressor mutant SUP (■), or a virus-free lysate prepared from mock-infected cells (♦). Tumors were measured every 2 days for 34 days and the average normalized values reflecting relative tumor size on each day were plotted. The initial tumor volume immediately before treatment was normalized to a relative size of 1.0. Error bars reflect the SEM.

Table 2.

Antitumor efficacy of the suppressor virus compared to the γ34.5 deletion mutant

| Virus | Dose | No. animals treated | ≥50% response | Complete response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUP | 2 × 107 | 18 | 72% | 22% |

| 2 × 106 | 5 | 60% | 40% | |

| 2 × 105 | 5 | 20% | 0% | |

| Δ34.5 | 2 × 107 | 18 | 39% | 0% |

| 2 × 106 | 5 | 0% | 0% | |

| 2 × 105 | 5 | 0% | 0% |

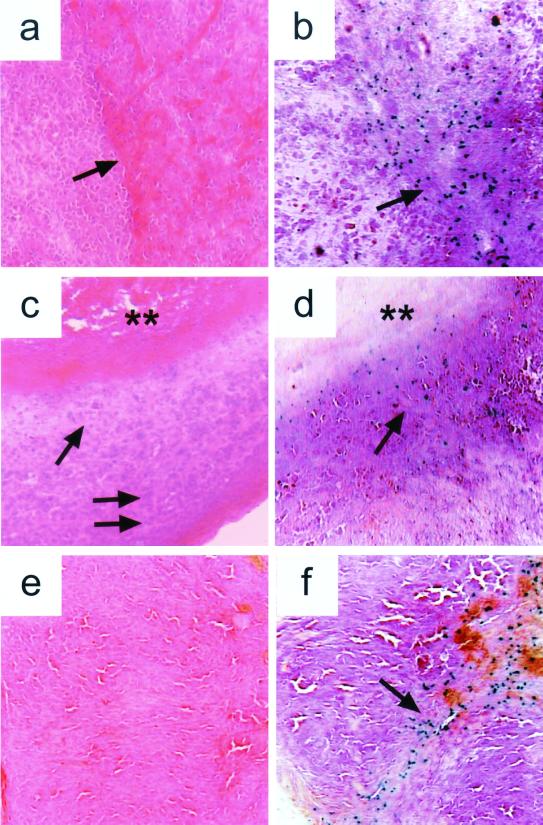

To examine sites of viral replication, tumors were harvested on days 3, 12, or 28, following injection with the SUP virus. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to evaluate overall histology, and sites of viral replication were identified by in situ staining for β-glucuronidase produced from a reporter gene present in the SUP virus. Because the β-glucuronidase reporter gene is under the control of a late viral promoter, its expression reflects active viral replication. On day 3, an early time point, pockets of infected cells are seen proximal to a region that contains viable tumor and within an area that contains extravasated red cells (Fig. 3 a and b). Day 12 is the point of maximum average regression, and a hypocellular area is observed between a necrotic central region and viable tumor at the periphery (Fig. 3c). Virus is detected in an area adjacent to the necrotic region (Fig. 3d). Finally, by day 28, viable tumor has been replaced by an acellular zone, possibly representing highly necrotic or scar tissue, and some infected cells are still present (Fig. 3 e and f). Thus, we can detect the SUP virus in the tumor at various stages of regression. Although multiple factors may contribute to tumor regression, these findings are consistent with idea that the cytolytic action of the replicating virus plays an important role in destroying the tumor.

Figure 3.

The suppressor virus is present in the human tumor xenograft at various stages of regression following a single intratumoral injection. BALB/c nu/nu mice harboring established, s.c. PC-3 tumors measuring 50 mm3 received a single injection of 2 × 107 pfu of the suppressor virus. On days 3 (a and b), 12 (c and d), and 28 (e and f) post-treatment, the animals were killed and the tumors explanted. Frozen sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (a, c, and e) or processed for in situ detection of the viral β-glucuronidase reporter gene product (b, d, and f). All sections are shown at 10× magnification. (a) By day 3, hemorrhage is noted centrally within the tumor (arrow). (b) Infected cells expressing β-glucuronidase are seen within this region of hemorrhage (arrow). (c) By day 12, a region of central necrosis (double asterisk) is surrounded by a zone of decreased cellularity (arrow) and a peripheral area of densely packed tumor cells (double arrow). (d) Infected cells (arrow) are observed in the area surrounding the central necrotic region. (e) By day 28, viable tumor has been largely replaced by an acellular residual mass. (f) Some infected cells are observed (arrow).

Discussion

Although large doses of HSV-1 γ34.5-based mutants have been safely administered to human cancer patients, the efficacy of these viruses as antitumor agents in animal models of human cancer is limited because of their reduced growth in tumor cells (5–8). We have modified the γ34.5 mutant virus by genetic selection such that it replicates more effectively in tumor cells in culture, yet remains as attenuated as the Δ34.5 virus in animals (18, 22). In this study, we demonstrate that the suppressor virus replicates better than the γ34.5 mutant in PC3 prostate cancer cells, and is a more potent antitumor agent in an animal model of human prostate cancer. Greater regression was observed in tumors that received a single intratumoral injection of the suppressor virus compared with the γ34.5 mutant virus. The enhanced efficacy of the suppressor mutant as an oncolytic virus was most apparent at reduced viral doses where the γ34.5 mutant was relatively ineffective. Although the suppressor mutant was more effective in achieving a 50% reduction of tumor volume in a larger number of animals than the γ34.5 mutant, only treatment with the suppressor virus yielded animals that completely responded and had no measurable tumor at the conclusion of the study period. Moreover, the number of animals that completely responded to treatment could potentially be even larger, because the small masses remaining in some animals at the end of the study appear to be composed predominately of acellular fibrous tissue and may not necessarily contain viable neoplastic cells. Further studies are required to discern whether this residual tissue contains any surviving tumor cells. These results demonstrate that the ability of existing replication-competent viruses to destroy tumors in vivo can be dramatically improved by the introduction of additional mutations into the viral genome. In the case of HSV-1, the suppressor mutation we describe enhances the ability of a γ34.5 mutant to replicate in human tumor cells and destroy tumors in vivo. A parallel effort aimed at improving the efficacy of replication-competent adenoviruses has identified existing mutant E1a alleles that enable the virus to more effectively destroy a broad range of cancer cells with defective cell-cycle checkpoints and enhance its oncolytic potential (23). Importantly, the increase in viral replication and oncolytic activity does not have to be accompanied by a commensurate increase in virulence.

A major limitation in the use of attenuated, replication-competent viruses to directly destroy tumors is the reduced growth of these weakened strains in many cell types, including cancer cells. Recent efforts have focused on augmenting the antitumor activity of these mutant viruses either by expressing ectopic trans genes that promote tumor eradication or attempting to correct for their limited replication potential through the selective expression of viral virulence genes in rapidly dividing cells (24, 25). Although both strategies succeed in increasing viral antitumor activity, the former approach does not address the replication defect of the attenuated virus, whereas the latter approach results in a virus with an undesirable increase in overall virulence. Our findings directly demonstrate that genetic selection can be used as a tool to isolate new mutant viral derivatives that exhibit substantially improved growth properties in human cancer cells, and that these viruses are more effective antitumor agents. These results have important implications for the rational design of attenuated, replication-competent viruses and the modification of the initial safe isolates into more potent, efficacious derivatives. Once a deletion is engineered into the virulence gene(s) to create an attenuated, recombinant virus, the ability of this weakened virus to replicate in tumor cells can then be enhanced by genetic selection. In the case of HSV-1, the defined suppressor mutation that alters Us11 expression radically improves the growth properties of the γ34.5 mutant virus without compromising its safety. This second mutation enables the virus to reduce the growth of human prostate cancer xenografts in mice more effectively than the Δ34.5 parent virus.

Although we chose to concentrate on prostate cancer because of the urgent need for new modalities of treatment and the accessibility of the human prostate to injection, the results described here are likely to be applicable to a wide variety of cancers. Large amounts of the γ34.5 mutant derivatives G207 and 1716 have already been safely administered to glioblastoma patients in a phase I trial (13, 14). Future work to establish efficacy, however, may benefit from the incorporation of our conclusion that a new γ34.5 derivative is a more potent therapeutic agent in animals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan Melamed for helpful discussions concerning the histology, and Michael Garabedian and Len Freedman for their critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Department of Defense and an award from CapCure.

Abbreviations

- HSV-1

herpes simplex virus type 1

- pfu

plaque-forming units

- SUP

suppressor

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Kirn D H. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:837–839. doi: 10.1172/JCI9761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heise C, Kirn D H. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:847–851. doi: 10.1172/JCI9762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martuza R. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:841–846. doi: 10.1172/JCI9744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markert J M, Gillespie G Y, Weichselbaum R R, Roizman B, Whitely R J. Rev Med Virol. 2000;10:17–30. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(200001/02)10:1<17::aid-rmv258>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers R, Gillespie G Y, Soroceanu L, Andreansky S, Chatterjee S, Chou J, Roizman B, Whitely R J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1411–1415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mineta T, Rabkin S D, Yazaki T, Hunter W D, Martuza R L. Nat Med. 1995;1:938–943. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kesari S, Randazzo B P, Valyi-Nagy T, Huang Q S, Brown S M, MacLean A R, Lee V M, Trojanowski J Q, Fraser N W. Lab Invest. 1995;73:636–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreansky S, He B, Gillespie G Y, Soroceanu L, Markert J, Chou J, Roizman B, Whitely R J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11313–11318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roizman B R, Sears A. In: Virology. Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P, Chanock R M, Hirsch M S, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, editors. New York: Raven; 1996. pp. 2231–2295. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou J, Kern E, Whitely R, Roizman B. Science. 1990;250:1262–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.2173860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLean A R, Ul-Fareed M, Robertson L, Harland J, Brown S M. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:631–639. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolovan C A, Sawtell N M, Thompson R L. J Virol. 1994;68:48–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.48-55.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rampling R, Cruickshank G, Papanastassiou V, Nicoll J, Hadley D, Brennan D, Petty R, MacLean A, Harland J, McKie E, et al. Gene Ther. 2000;7:859–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markert J M, Medlock M D, Rabkin S D, Gillespie G Y, Todo T, Hunter W D, Palmer C A, Feigenbaum F, Tornatore C, Tufaro F, Martuza R L. Gene Ther. 2000;7:867–874. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He B, Gross M, Roizman B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;94:843–848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou J, Chen J J, Gross M, Roizman B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10516–10520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou J, Roizman B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3266–3270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohr I, Gluzman Y. EMBO J. 1996;15:4759–4766. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulvey M, Poppers J, Ladd A, Mohr I. J Virol. 1999;73:3375–3385. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3375-3385.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cassady K, Roizman B. J Virol. 1998;72:7005–7011. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7005-7011.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cassady K, Gross M, Roizman B. J Virol. 1998;72:8620–8626. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8620-8626.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohr I, Sternberg D, Ward S, Leib D, Mulvey M, Gluzman Y. J Virol. 2001;75:5189–5196. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5189-5196.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heise C, Hermiston T, Johnson L, Brooks G, Sampson-Johannes A, Williams A, Hawkins L, Kirn D. Nat Med. 2000;6:1134–1139. doi: 10.1038/80474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker J N, Gillespie G Y, Love C E, Randall S, Whitely R J, Markert J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2208–2213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040557897. . (First Published February 18, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.040557897) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung R Y, Saeki Y, Chiocca E A. J Virol. 1999;73:7556–7564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7556-7564.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]