Abstract

Small-colony variants (SCVs) are slow-growing variants of human bacterial pathogens. They are associated with chronic persistent infections, and their biochemical identification and antimicrobial treatment are impaired by altered metabolic properties. To contribute to the understanding of SCV-mediated infections, we analyzed a clinical SCV isolate derived from a chronic prosthetic hip infection. A sequence analysis of housekeeping genes identified an Enterobacter hormaechei-like organism. The SCV phenotype, with growth as microcolonies, was caused by a block within the heme biosynthesis pathway through deletion of the hemB locus, as shown by hybridization and complementation experiments. At a low frequency, large-colony variants (LCVs) arose that were dependent on exogenous hemin. To investigate this phenomenon, we cloned and sequenced the 5.8-kb hemin uptake system, denoted ehu. Gene expression analysis indicated regulation of this locus in wild-type bacteria by the global iron regulator Fur. Inactivation of Fur in LCVs caused the derepression of ehu expression and facilitated bacterial growth. Genetic alterations of the fur locus in LCVs were identified as insertions of IS1A elements and point mutations. In contrast, SCVs could utilize exogenous hemin only in the absence of iron. Thus, we provide the first molecular characterization of the growth properties of a clinical SCV isolate, which may help to improve the diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients with chronic persistent infections.

The isolation of small-colony variants (SCVs) from clinical specimens has been reported since the beginning of the last century (16). These growth-deficient variants are formed by a wide range of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Although SCVs have repeatedly been associated with persistent and recurrent infections of the skeletal system, the heart, the lung, and indwelling medical devices, their precise role in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases has not been defined (13).

SCVs are characterized by reduced growth on routine culture media, with colony sizes of <1/10 the size appropriate for the species. Biochemical differentiation is impaired by decreases in metabolic properties, such as the fermentation of carbohydrates. Enhanced resistance against various antibiotics, particularly aminoglycosides, complicates antibiotic therapy and medical management. A deficiency in aerobic respiration is indicated by auxotrophy for hemin, thiamine, or menadione. SCV strains are characterized by an unstable growth behavior. Rapidly growing subpopulations, so-called revertants or large-colony variants (LCVs), arise spontaneously at low frequencies (24).

Despite a considerable number of reports about the isolation of SCVs from clinical specimens, the underlying molecular mechanisms of the altered growth properties have not been investigated. Members of our laboratory recently presented the first detailed molecular characterization of a clinical SCV strain isolated from a chronic prosthetic hip infection (29). The SCV phenotype of the gram-negative isolate Z-2376 was due to a deletion of the hemB gene. hemB codes for the single pathway enzyme, porphobilinogen synthase, that is required for heme biosynthesis (2). Heme derivatives are key components of the electron transfer apparatus, and heme deficiency causes a broad range of metabolic disturbances and a lack of intracellular energy. In fact, in vitro mutations in heme biosynthesis genes have been reported to generate strains with reduced growth rates, similar to the SCV phenotype (18, 34).

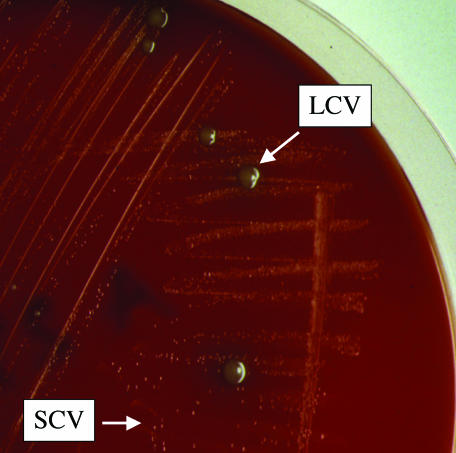

The examined clinical isolate, Z-2376, showed an unstable growth behavior, forming two colony types (29). On rich, hemin-containing agar plates, the majority of the strain grew as microcolonies (SCVs, with <0.1-mm diameters after 48 h at 37°C). Between these, large colonies (LCVs, with >1.5-mm diameters after 48 h at 37°C) appeared spontaneously with a frequency of 2 × 10−3 (Fig. 1). In contrast, both colony types grew as microcolonies on hemin-free agar plates. Although the emergence of fast-growing subpopulations among SCVs has been previously noted, the underlying functional mechanisms and the clinical importance are unknown (24). For the present study, we investigated this phenomenon and identified derepression of the global iron regulator Fur and an enhanced uptake of exogenous hemin by the hemin uptake system ehu to compensate for the heme biosynthesis defect.

FIG. 1.

Growth morphology of Z-2376. Z-2376 was grown on a Columbia blood agar plate for 48 h at 37°C. The majority of clones formed typical microcolonies characteristic for SCVs. A small subpopulation of Z-2376 grew as large colonies (LCVs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Z-2376 was isolated from a chronic prosthetic hip infection (29). The type strain of Enterobacter hormaechei ATCC 49162 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Escherichia coli K-12 strain DH5α was used for the cloning of hemB. E. coli strain W3110 was used as a Fur-proficient strain, and its fur-negative derivative H1673 was used as an E. coli fur mutant (33). The E. coli strain TOP10 was obtained from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany). E. coli strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani medium, and strains Z-2376 and DH5αhemB were grown on Columbia blood agar plates or in brain heart infusion broth (BHI; Oxoid, Wesel, Germany). Nutrient broth (NB) supplemented with 0.25 mM 2,2′-dipyridyl (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) (NBD) was used to generate low-iron growth conditions. Hemin (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved at a concentration of 25 mM in 20 mM NaOH. Antibiotic selection was performed with tetracycline (20 μg/ml) and ampicillin (100 μg/ml).

Selection of a heme biosynthesis-deficient mutant.

The exposure of bacteria to aminoglycosides at or above their MICs was used to select for respiration-deficient mutants (Res−) (14, 31). Res− mutants are unable to produce a proton gradient across the cytoplasmic membrane, which is a prerequisite for the uptake of aminoglycosides into bacterial cells. Most of the Res− mutants carried defects in heme biosynthesis genes (18). For generation of a mutant deficient in heme biosynthesis, E. coli DH5α was exposed to 8 μg of gentamicin/ml. The resulting microcolonies were analyzed by PCR and DNA-DNA hybridization to verify the presence or absence of the genes involved in the biosynthesis of heme. One mutant harboring a complete deletion of the hemB gene was chosen for further experiments and was named DH5αhemB.

Molecular biological procedures.

Plasmids and cosmids were isolated with NucleoBond anion-exchange columns (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Chromosomal DNA was prepared by use of proteinase K and hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the protocol of Rahn et al. (27). Standard procedures were used for PCR, ligation, electroporation, transformation, and analysis of DNA and RNA (1). For cloning procedures, the proofreading Pfu DNA polymerase was used (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). For DNA-DNA hybridization experiments, probes were generated and labeled with digitoxin-conjugated dUTP (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) by PCR. DNA sequencing was performed by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method in an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The ehu operon and the fur gene were sequenced by primer walking in both directions. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis were performed as described previously (28).

RT-PCR analysis.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed with the Access Quick RT-PCR system (Promega GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and the primers HR-361 (5′-GATCCGGCGCTGATCAACG-3′) and HR-1108 (5′-TCTCATCCTGCAACCAGCC-3′) for ehuA. Amplification of the housekeeping gene hsp60 (accession no. AB008137) with the primers HSP60-1 (5′-GGTAGAAGAAGGCGTGGTTGC-3′) and HSP60-2 (5′-ATGCATTCGGTGGTGATCATCAG-3′) was used as a control.

Identification and characterization of the hemin uptake locus of Z-2376.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from an LCV of Z-2376, partially digested with Sau3A, ligated into the BamHI site of the cosmid vector pLAFR2 (6), and packed in vitro (Stratagene). DH5αhemB was infected with recombinant phages and screened for tetracycline resistance and rapid growth in the presence of 8 μM hemin. Four independent colonies were isolated and denoted DH5αhemB pHR1 to pHR4. A restriction fragment analysis of the cosmids pHR1 to pHR4 showed identical patterns with three different enzymes.

Cloning of the hemB gene.

For complementation of the hemB-deficient clinical isolate Z-2376 in trans, the hemB gene of DH5α was amplified as a 1.37-kb fragment by use of the primers HemB-1 (5′-GGTTGGATCCTTGGGGATAAACCG-3′) and HemB-2 (5′-GTATGGATCCTATGAATATGCAACAAAG-3′). Both primers include BamHI sites at their 5′ ends. The amplicon was digested with BamHI, ligated into the broad-host-range vector pSUP102, generating pGH1, and verified by sequencing (8).

Characterization of the fur locus in Z-2376.

The fur gene of the clinical isolate Z-2376 was amplified by use of the following primers deduced from conserved regions of the fur genes of E. coli (accession no. D90707.1), Klebsiella pneumoniae (accession no. L23871.1), and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (accession no. AE008728.1): FldA-1 (5′-GAAGAGATYGAYTTCAAYGGCAAA-3′) and Fur-1 (5′-CAATNTCTTCACCNATATCGATCAG-3′) or Fur-2 (5′-GGTGYGATGTATGACCTGAAAAA-3′). Primers FldA-EH (5′-GACGATATCCTTAACGCCTGA-3′) and Fur2-EH (5′-CCTTCGGCACAGTGACCGTA-3′) were used for specific amplification of fur from Z-2376. IS1A PCR was done with the primers IS-1-76 (5′-CTGTCCCTCCTGTTCAGCTA-3′) and IS-1-711 (5′-GTCATGCAGCTCCACCGATT-3′), deduced from a known sequence (accession no. X52534).

EhuA antiserum preparation.

For preparation of a rabbit antiserum against EhuA, a gene fragment of ehuA representing bp 643 to 1529 of the coding sequence was amplified by use of primers HRexT-1 (5′-CACCAGGGCGCCAAACGACGAAT-3′) and HRexT-2 (5′-CGGTAGTGGAGATGTAATCTT-3′), ligated into pET100, and transformed into E. coli strain TOP10 (Invitrogen). The resulting construct was verified by sequencing and denoted pETEhuA-1. Plasmid pETEhuA-1 was transformed into E. coli BL21 Star (Invitrogen), and gene expression was induced with 2 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 6 h at 37°C. The 33-kDa recombinant protein (rEhuA) was purified under denaturing conditions as recommended by the manufacturer. A 2-month-old New Zealand White rabbit was immunized with 150 μg of rEhuA and complete adjuvant (ABM adjuvant; Sebak GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany), followed by three booster immunizations of 150 μg of rEhuA and incomplete adjuvant each time.

Reporter gene analysis.

EhuA-luciferase reporter fusions were constructed by using pCJYE138-L, a recently described pACYC184 derivative (12). A 1-kb ehuA promoter fragment carrying the ehuA promoter and the first eight codons was generated by PCR amplification from Z-2376 LCV DNA with primers HR-P-1 (5′-TGTCCTAAGCTTGAGCTCTCCTGTCCGGTGGGCT-3′) and HR-P-2 (5′-GCAGAGGATCCAGACGCGGATTGCAGGTGTGG-3′). The gene fragment was cloned into pCJYE138-L, replacing the HindIII/BamHI fragment (yopE insert); the resulting construct was denoted pEhuA-Luc. Luciferase reporter gene assays were performed as described by Jacobi et al. (12). In brief, cells were cultured for 6 h and then harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysate buffer, and frozen at −20°C. Determination of the optical density of the culture and serial plating were performed to standardize the bacterial lysate. The reporter gene activity of the bacterial lysates was measured for 10 min with a charge-coupled device camera.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the ehu operon (AJ538328), the fur gene (AJ539162), and the IS1A (AJ539161) element of the clinical isolate Z-2376 have been deposited in GenBank.

RESULTS

Biochemical and genetic differentiation of Z-2376.

The biochemical properties of the clinical strain Z-2376 isolated from a chronic prosthetic hip infection were not indicative of any known species (29). Z-2376 was therefore presumptively identified previously as E. coli based on its high level of 16S ribosomal DNA sequence similarity (>99%) (accession no. Z83204.1). Since the low reliability of 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing for the differentiation of Enterobacteriaceae has been demonstrated, we additionally performed sequencing of a number of housekeeping genes (10, 32). Partial sequencing of hsp60 and rpoB identified Z-2376 as a member of the genomic cluster X of the Enterobacter cloacae complex, most closely related to E. hormaechei (11; also data not shown).

Reversion of the growth defect of Z-2376 by complementation with the hemB gene of E. coli.

DNA hybridization experiments had previously indicated that the hemB gene is deleted in the small and the large colony types of the clinical isolate Z-2376 (29). To verify that the deletion of hemB is responsible for the growth defect of Z-2376, we introduced the hemB gene of E. coli in the plasmid pGH1 into the SCV form of Z-2376. The resulting strain, Z-2376pGH1, exhibited the typical growth behavior of Enterobacteriaceae on MacConkey agar plates, with a colony size exceeding 1.5 mm after incubation at 37°C for 18 h, indicating successful restitution of the genetic defect. In addition, the metabolic properties of Z-2376pGH1 were analyzed by the API20E identification system of bio-Merieux Ltd. (Marcy l'Étoile, France). The resulting numerical code of Z-2376pGH1 (3305573, which is a very accurate identification of Enterobacter species) supported the genotypic identification of Z-2376 as a member of the E. cloacae complex. Thus, the resulting phenotype of the hemB-complemented SCV strain demonstrated that the deletion of hemB was indeed responsible for the growth deficiency of Z-2376 SCVs.

Cloning and sequencing of the hemin uptake locus ehu from Z-2376.

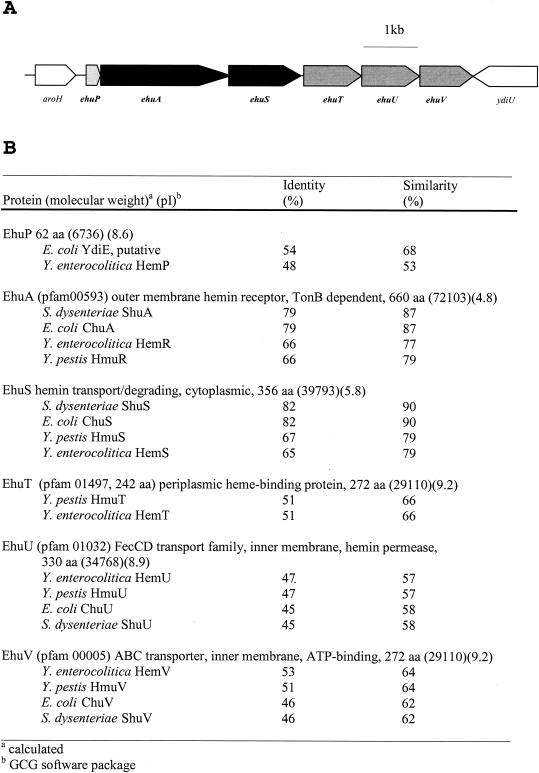

Feeding experiments suggested that the colony size of Z-2376 LCVs was dependent on the presence of hemin (29). In contrast to Z-2376 SCVs, Z-2376 LCVs were able to utilize exogenous hemin, resulting in a larger colony size on hemin-containing BHI or Columbia blood agar plates (Fig. 1). Since the cell membranes of gram-negative bacteria are impermeable for heme, specific hemin uptake systems are required (7). However, E. coli K-12 has been shown to lack heme uptake systems and no such system has been described for members of the E. cloacae complex. In order to identify genes responsible for the utilization of hemin by Z-2376 LCVs and subsequently to identify the mechanism controlling the formation of LCVs in Z-2376, we constructed a Sau3A cosmid library of Z-2376 LCVs in an E. coli hemB mutant (DH5αhemB) and screened them for growth on hemin-containing medium. Four independent clones exhibited hemin-dependent growth behavior, forming normally sized colonies (>1.5 mm) on BHI-hemin-agar plates but forming microcolonies (<0.1 mm) on nonsupplemented growth medium. A restriction fragment analysis of the isolated cosmids using three different enzymes showed identical restriction patterns. Sequence analysis identified a previously unknown operon of 5.8 kb with homologies to reported hemin uptake loci in other gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 2). A 10-kb EcoRI/SphI fragment which encoded the complete operon and was sufficient to promote the growth of DH5αhemB on hemin-containing agar was subcloned (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Hemin uptake system ehu of Z-2376. (A) Genetic organization of the hemin uptake system ehu of Z-2376. (B) Comparison of the proteins encoded by the ehu locus with known related heme proteins. Accession numbers for proteins are as follows: Y. enterocolitica proteins, X68147 and X77867; S. dysenteriae proteins, U64516; E. coli proteins, U67920 and D90813; and Y. pestis proteins, U60647.

The genetic organization of the hemin uptake locus of Z-2376 LCVs was denoted ehu (for Enterobacter hemin uptake). It revealed close homology to the hem operon of Yersinia enterocolitica. Also, the first protein encoded by this operon, denoted EhuA, exhibited the following conserved features of outer membrane hemin receptor proteins: (i) an N-terminal leader sequence of 29 amino acids (aa), (ii) a TonB box (aa 31 to 38), (iii) region V of Ton B-dependent proteins (aa 523 to 531), (iv) FRAP (aa 434 to 437) and NPNL (aa 462 to 465) motifs as well as the conserved histidine residues (aa 115 and 451) recently described by Bracken et al. (3), and (v) a C-terminal aromatic tryptophan residue required for proper incorporation into the outer membrane (15). Additionally, a putative Fur box (GATAATGATTATCATTGT) was found 296 to 313 bp upstream of the putative transcriptional start site of the operon, indicating iron-dependent regulation (4).

Subsequently, possible genetic differences between the hemin-utilizing LCV type of Z-2376, the SCV type of Z-2376, and the type strain of E. hormaechei were investigated. DNA probes recognizing a variety of different genes of the ehu operon hybridized specifically with chromosomal DNAs of the E. hormaechei type strain and both colony variants (SCVs and LCVs) of Z-2376 (data not shown). Also, sequencing of PCR products amplified from the E. hormaechei type strain and Z-2376 SCVs and LCVs showed that all three strains encoded the complete ehu hemin uptake system. Alterations of the DNA sequence, particularly within the promoter region of ehuA, could not be identified. Thus, we identified and characterized the Enterobacter hemin uptake system ehu. However, no genetic differences were detected between the type strain and SCV subpopulations.

ehu is regulated by Fur in an iron-dependent fashion.

Hemin uptake systems in Enterobacteriaceae are controlled by the global regulator Fur and are upregulated under conditions of low iron concentrations (4, 7, 9, 17). Fur binds as a transcriptional repressor to a consensus sequence know as the Fur box located upstream of all Fur-regulated genes. Similarly, a putative Fur box was identified in Z-2376 upstream of the first gene of the ehu operon, ehuA. To verify that genes of the ehu operon were regulated by Fur in an iron-dependent fashion, we constructed an EhuA-luciferase reporter fusion. Expression analysis was subsequently performed with Fur-positive E. coli W3110 and the Fur-deficient derivative H 1673 under iron-rich and iron-depleted conditions. As expected for a Fur-regulated gene, EhuA-luciferase was produced by the wild-type strain exclusively in iron-depleted medium (NBD) (54,097 ± 6,770 relative light units [mean ± standard deviation] versus 899 ± 101 in NB). In contrast, a high reporter gene activity was found for the E. coli fur mutant H 1673 regardless of the presence or absence of iron (81,002 ± 7,171 relative light units in NBD and 53,314 ± 7,964 in NB). Thus, the reporter gene analysis performed with E. coli suggested that the ehu operon is controlled by the global iron regulator Fur, leading to upregulation under conditions of low iron concentrations. The regulation of the ehu operon might differ in Z-2376. However, attempts to analyze ehu regulation in Z-2376 by genetic manipulations, e.g., the construction of a fur mutant, failed.

EhuA is dysregulated in both colony types of Z-2376.

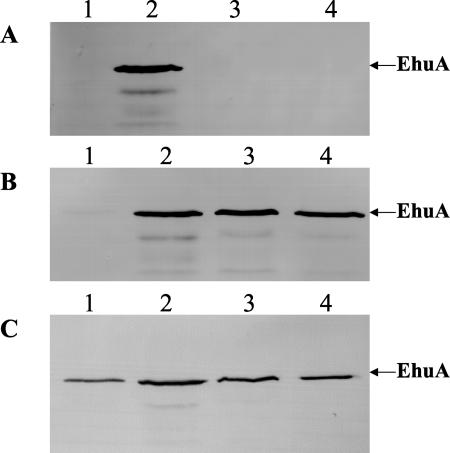

For confirmation of the iron-dependent expression of EhuA, an immunoblot analysis of whole bacterial cell lysates was performed using a polyclonal rabbit antiserum raised against EhuA. Analysis of the type strain of E. hormaechei and the hemB-complemented Z-2376pGH1 strain revealed that there is indeed induction of EhuA synthesis in the absence of iron (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4).

FIG. 3.

Production of EhuA in Z-2376 SCVs and LCVs as well as E. hormaechei. An immunoblot analysis was performed with whole-cell lysates (30 μg) and a rabbit antiserum specific for EhuA (72.1 kDa). The different strains were grown at 37°C for 6 h in NB (A), iron-depleted NBD (B), or iron-depleted NBD containing 8 μM hemin (C). Lanes 1, Z-2376 SCVs; lanes 2, Z-2376 LCVs; lanes 3, Z-2376pGH1; lanes 4, E. hormaechei ATCC 49162.

Whereas both colony types of Z-2376 encode the ehu hemin uptake system, only the LCV subtype of Z-2376 was able to utilize exogenous hemin. Accordingly, the production of EhuA in Z-2376 SCVs and LCVs in the presence or absence of iron was compared. Unexpectedly, Z-2376 LCVs were able to produce EhuA even in the presence of iron, indicating a derepressed expression of ehuA. In contrast, immunoblot analysis failed to detect any EhuA expression in Z-2376 SCVs, even under iron-depleted conditions (Fig. 3A and B). However, Z-2376 SCVs were able to produce EhuA in iron-depleted medium in the presence of hemin (Fig. 3C). Thus, in contrast to the derepressed expression of ehuA in Z-2376 LCVs, the Z-2376 SCVs produced EhuA in iron-depleted medium only in the presence of hemin.

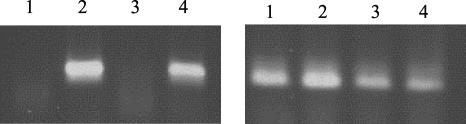

Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of EhuA.

RT-PCR analysis was performed to investigate whether the lack of EhuA production in Z-2376 SCVs cultured in iron-depleted, hemin-free medium was a transcriptional or posttranscriptional phenomenon. As shown in Fig. 4, ehuA was transcribed in Z-2376 SCVs in iron-depleted medium independent of the presence or absence of hemin. The posttranscriptional stop of EhuA production in hemin-free medium was an unexpected finding. Notably, a direct influence of hemin on the regulation and expression of Fur-regulated genes has not previously been described for members of the Enterobacteriaceae.

FIG. 4.

Transcriptional expression of ehuA in Z-2376 SCVs. RNAs were prepared from Z-2376 SCVs incubated in different media for 2 h at 37°C. RT-PCR analyses of ehuA (741 nucleotides; left) and hsp60 (350 nucleotides; right) are shown. Lanes 1, Z-2376 SCVs grown in NB; lanes 2, Z-2376 SCVs grown in iron-depleted NBD; lanes 3, Z-2376 SCVs grown in NB plus 8 μM hemin; lanes 4, Z-2376 SCVs grown in iron-depleted NBD plus 8 μM hemin.

Correlation between EhuA production and utilization of hemin in Z-2376.

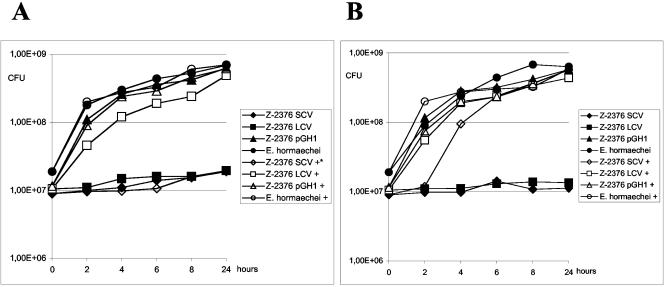

To analyze if the production of EhuA correlated with the utilization of exogenous hemin in Z-2376, we performed growth experiments in different culture media in the present or absence of hemin (Fig. 5). Corresponding to the size of the colonies on hemin-containing agar plates, Z-2376 LCVs, but not SCVs, utilized hemin in iron-containing media and multiplied to the same extent as the E. hormaechei type strain. In the absence of hemin, both colony types of Z-2376 were not able to grow in NB. In contrast, Z-2376 SCVs multiplied in iron-depleted medium in the presence of hemin, suggesting that the production of EhuA was functional, enabling the strain to utilize hemin under conditions of low iron concentrations. Attempts to inactivate ehuA in Z-2376 SCVs or LCVs by marker exchange using kanamycin- or chloramphenicol-resistant genes and temperature-sensitive suicide vectors failed due to a marked resistance of Z-2376 against transformation. Thus, in contrast to the iron-independent utilization of hemin by LCVs, Z-2376 SCVs were able to utilize hemin and to multiply comparably to an Enterobacter wild-type strain only under the appropriate conditions.

FIG. 5.

Iron- and hemin-dependent growth of the different colony variants of Z-2376. Z-2376 SCVs and LCVs as well as E. hormaechei ATCC 49162 were grown in NB (A) or iron-depleted NBD (B). Medium supplementation with 8 μM hemin is indicated with “+” symbols. Bacterial growth was quantified by plating of serial dilutions on blood agar plates. The emergence of LCV variants in SCV cultures was excluded by repeated subcultures showing exclusively SCV-type colonies. The data represent one of three identical experiments.

Cloning of the Z-2376 fur gene.

Z-2376 LCVs were able to produce EhuA independent of the presence of iron, indicating a derepressed expression of ehuA. Therefore, we next investigated a possible mutational inactivation of the global iron regulator fur in Z-2376 LCVs. Since the sequence of the Enterobacter fur gene was unknown, the fur gene of Z-2376 SCVs was initially cloned and sequenced by using oligonucleotides deduced from conserved regions upstream and downstream of the E. coli fur gene. Gene products of the appropriate size could be amplified from Z-2376 SCVs. A DNA sequence analysis of the PCR products revealed one open reading frame (ORF), with 447 bp coding for 148 aa. The translated gene product showed 95% identity and 98% similarity to Fur of E. coli. The promoter region upstream of the ORF contained a putative Fur-binding site (64 to 91 bp upstream of the start codon) and a putative OxyR-binding site (215 to 263 bp upstream of the start codon). Both motifs were also present in the E. coli fur operon (35). These results strongly suggested that we amplified the fur gene of Z-2376 SCVs.

Mutations of the fur gene are responsible for the formation of LCVs in Z-2376.

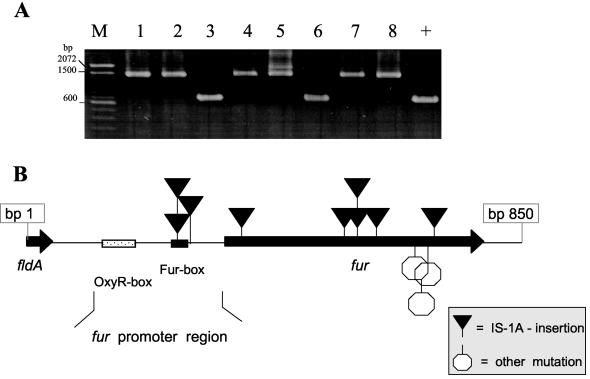

To determine whether the genetic organization of the fur gene was altered in Z-2376 LCVs, we selected 12 independent colonies of Z-2376 showing the typical growth properties of LCVs. All isolates were analyzed by PCR using oligonucleotides located upstream and downstream of fur. Strikingly, in comparison to the fur locus of Z-2376 SCVs, the PCR products of nine Z-2376 LCV isolates were about 800 bp larger (Fig. 6A). DNA sequence analyses revealed that in each case the same insertion sequence (IS) element was inserted more or less randomly within the fur gene. Six isolates harbored the IS element within the coding sequence of fur, at positions 38, 174, 177 (two times), 233, and 334. Three other isolates harbored the IS element within the promoter region, 45 or 65 (two times) bp upstream of the start codon (for an overview, see Fig. 6B). The identified IS element exhibited 99% identity to known IS1A elements described for E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae (accession no. AJ278144.1) (20). Similar to other described insertions of IS1 elements, each IS1A fur insertion resulted in a duplication of 9 bp. However, no frameshift mutations within the two ORFs, insA and insB, of the IS1 element, which have been described to increase the frequency of transposition, were detected (5). Subsequent hybridization experiments using labeled IS1A probes revealed that all nine LCV isolates with identified IS element insertions within the fur gene contained six IS1A copies in their chromosomes, whereas Z-2376 SCVs and Z-2376pGH1 harbored five (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

PCR analysis of the fur locus of Z-2376 LCVs. (A) PCR analysis of the fur locus of different LCV-type colonies (LCVs 1 to 8) with primers FldA-EH and Fur2-EH. As a control, the result for Z-2376 SCVs is included (+). M, 100-bp DNA ladder. (B) Schematic drawing of all mutations within the fur locus identified in LCV-type colonies of Z-2376.

Additionally, we examined the underlying mechanism of fur inactivation of the remaining three LCV isolates, which did not show enhanced lengths of the fur locus. Careful sequence analysis revealed that there were indeed minor mutations of the fur gene in all three cases (Table 1). Besides a frameshift mutation leading to a premature stop, a point mutation as well as a short deletion responsible for an amino acid exchange within the Fur protein was found. Together, these results strongly suggest that an inactivation of fur was responsible for the derepression of the ehu locus in LCVs. Thus, whereas the deletion of hemB in SCVs facilitated growth only in the absence of iron, the additional inactivation of fur and derepression of ehu allowed LCVs of Z-2376 to internalize exogenous hemin independent of the presence of low iron concentrations.

TABLE 1.

Mutations within the fur gene of three different Z-2376 LCV isolates

| Isolate no. | Nucleotide position of mutation | Description of mutation | Mutated amino acid |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 337 | Duplication of 16 nucleotides plus C | Frameshift after aa 112 |

| 6 | 287 | G→T | Cys 96→Phe96 |

| 11 | 294-296 | Deletion of 3 nucleotides (GGT) | Lys 98 + Val 99→Asp |

DISCUSSION

Infections caused by SCV pathogens require a high level of attention and careful management from clinical laboratories and clinicians. SCVs often trigger long-lasting and recurrent infections and exhibit significant resistance to many antibiotics. Slow growth on standard culture media, altered biochemical properties, and colony polymorphisms frequently lead to insufficient or false identification in routine diagnostic laboratories. In addition, the emergence of SCVs may significantly contribute to the chronic persistent course of the infection. Very little is known about the effect of the reduced and unstable growth of SCVs on the pathogenesis of infection. It has been speculated that once a slow-growing SCV subpopulation of the original pathogen has been selected, the course of infection may slow down from a rapid, ongoing infection to a chronic, persistent one (13, 25, 26). Thus, the quiescent state of SCV isolates may trigger therapy-resistant chronic infections. In contrast, the appearance of more rapidly growing LCVs may be the reason for the recrudescence of SCV-mediated infections.

Here we present the first characterization of the underlying molecular mechanisms that lead to the development of slow-growing SCVs as well as the reemergence of rapidly proliferating LCVs derived from a clinical isolate of a chronic prosthetic hip infection. Our description also illustrates the typical problems that arise with routine laboratory biochemical and sequence-based identification techniques. Only sequencing of several housekeeping genes revealed that the SCV strain Z-2376 was an E. hormaechei-like organism and a member of the genomic cluster X of the E. cloacae complex. Therefore, this report adds another organism to the list of possible SCV-forming strains and stresses the general potential of this ill-defined phenomenon.

DNA hybridization and complementation experiments demonstrated that the deletion of the hemB gene was responsible for the reduced growth rate of SCV Z-2376 (29). HemB catalyzes an essential step in the heme biosynthesis pathway. Hemin itself is required as a cofactor of a variety of important enzymes, such as catalase, and of respiratory cytochromes. Therefore, the lack of heme biosynthesis results in a pleiotropic phenotype with (i) an incapability of generating energy from proton motive force, (ii) a lack of energy-dependent transport across the bacterial membrane, and (iii) enhanced susceptibility to oxidative stress (19). Heme biosynthesis mutants grow normally under anaerobic conditions; however, in an aerobic atmosphere, these mutants exhibit a distinct growth deficiency similar to the phenotype of SCVs (34).

At a low frequency, SCVs form fast-growing subpopulations, so-called revertants or LCVs. A careful analysis of this phenomenon led to the identification of the hemin uptake system ehu, the first hemin uptake system described for Enterobacter sp. The ehu operon was inserted between aroH and ydiU and exhibited the highest homology to the hemin uptake system hem of Y. enterocolitica. Other yet unknown hemin uptake systems may also contribute to the utilization of exogenous hemin in Z-2376. Multiple hemin uptake systems have been described for other gram-negative bacteria, such as Yersinia spp., Vibrio cholerae, and P. aeruginosa (21, 23, 30). However, hybridization experiments using low-stringency conditions and probes for ehuA or the alternative hemin uptake system of Yersinia spp. failed to detect a second hemin uptake system in Z-2376 (data not shown).

Similar to homologous hemin uptake systems in other gram-negative bacteria, ehu was regulated by the global repressor Fur in an iron-dependent manner. Fur is known as an important regulator, controlling more than 90 genes in E. coli, including a set of virulence factors (9). Derepression of ehu by the inactivation of Fur in LCV subpopulations was identified to facilitate normal growth on hemin-containing media. Interestingly, fur mutants have not been associated with an enhanced pathogenic potential so far. Spontaneous inactivation of Fur most often occurred by the insertion of IS1A elements. Phase variation due to IS insertions has been reported for many genera (18, 36), but IS insertions have never been described for fur. IS1A insertions in fur appeared to be stable, since a transition from the LCV to the SCV phenotype was not observed. In addition to IS1A insertions, other mutations within the fur gene were identified that impaired the regulatory functioning of Fur. However, the formation of LCVs in other SCV strains could be caused by other mechanisms. For example, Lewis et al. described unstable E. coli hemB mutants that emerged in vitro and harbored a precise excision of the IS2 element from hemB (18).

To summarize the results of the in vitro experiments, the growth of SCVs and LCVs of Z-2376 was dependent on the presence of hemin and iron. Due to the deletion of hemB, both types of colony variants were defective in heme biosynthesis, and due to the presence of ehu, both compensated for the defect by utilizing exogenous hemin. In the absence of hemin, the growth of both types of colony variants was strongly reduced irrespective of the presence of iron. The presence of hemin and iron promoted the rapid growth of LCVs but not SCVs. LCVs carried second mutations in fur, resulting in the derepression of the heme uptake system ehu, the production of the hemin receptor EhuA, the utilization of hemin, and the acceleration of growth. In contrast, the fur gene remained unaltered in SCVs, and in the presence of iron, Fur repressed the transcription of ehu, EhuA was not produced, and hemin was not utilized, resulting in reduced growth and the formation of microcolonies. In iron-depleted, hemin-containing medium, both colony types multiplied equally well. For LCVs, ehu remained derepressed and hemin was utilized. For SCVs, the absence of iron resulted in the transcription of ehu and subsequently in the utilization of hemin.

Interestingly, EhuA was only produced by SCVs under iron-deficient conditions in the presence of hemin. A direct influence of hemin on the expression of hemin uptake systems in Enterobacteriaceae has not previously been described. However, since ehu was regulated independently of hemin in the E. hormaechei type strain, the hemin-dependent production of Ehu in Z-2376 SCVs might have been due to a lack of energy in this heme biosynthesis-negative mutant.

The in vitro growth behavior of Z-2376 may be of relevance for in vivo conditions. Importantly, iron is restricted inside the mammalian host and hemin may be available for a pathogen, particularly at the site of infection and inflammation. Thus, SCVs may not persist in a quiescent state inside the host as recently postulated. The expression of the hemin uptake system compensated for the chromosomal deletion of hemB in vivo. Fur inactivation and LCV formation of Z-2376 occurred spontaneously at a low frequency under in vitro conditions. The occurrence of a hemB fur double mutant might be advantageous under microaerophilic conditions with variable iron and hemin concentrations. To investigate this question, we are currently developing an animal model. This will also allow for the analysis of other important features, such as the production of virulence factors (e.g., capsular polysaccharides and hemolysin), of SCV strains. A recent report by Musher et al. demonstrated a similar pathogenic potential of gentamicin-resistant SCVs compared to their parental strain (22). However, this study used in vitro-generated SCVs with an unknown molecular background.

In conclusion, we have presented the first molecular characterization of the mechanisms that lead to the development of SCVs and demonstrated a critical role for the regulation of the hemin uptake system in the emergence of fast-growing subpopulations. These results advance our understanding of the mechanisms that contribute to the development of chronic persistent infections and will help us to develop new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to improve the clinical management of infected patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Giesela Anding for excellent expertise.

The German Research Association (DFG) in the context of a special research field (SFB no. 576) funded this study.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1989. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 2.Beale, S. I. 1996. Biosynthesis of heme, p. 731-748. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 3.Bracken, C. S., M. T. Baer, A. Abdur-Rashid, W. Helms, and I. Stojiljkovic. 1999. Use of heme-protein complexes by the Yersinia enterocolitica HemR receptor: histidine residues are essential for receptor function. J. Bacteriol. 181:6063-6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escolar, L., J. Perez-Martin, and V. de Lorenzo. 1999. Opening the iron box: transcriptional metalloregulation by the Fur protein. J. Bacteriol. 181:6223-6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escoubas, J. M., M. F. Prere, O. Fayet, I. Salvignol, D. Galas, D. Zerbib, and M. Chandler. 1991. Translational control of transposition activity of the bacterial insertion sequence IS1. EMBO J. 10:705-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman, A. M., S. R. Long, S. E. Brown, W. J. Buikema, and F. M. Ausubel. 1982. Construction of a broad host range cosmid cloning vector and its use in the genetic analysis of Rhizobium mutants. Gene 18:289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genco, C. A., and D. W. Dixon. 2001. Emerging strategies in microbial haem capture. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guiney, D. G., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. The DNA-protein relaxation complex of the plasmid RK2: location of the site-specific nick in the region of the proposed origin of transfer. Mol. Gen. Genet. 176:183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hantke, K. 2001. Iron and metal regulation in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauben, L., E. R. Moore, L. Vauterin, M. Steenackers, J. Mergaert, L. Verdonck, and J. Swings. 1998. Phylogenetic position of phytopathogens within the Enterobacteriaceae. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:384-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann, H., and A. Roggenkamp. 2003. Population genetic study of the Enterobacter cloacae complex. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5306-5318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobi, C. A., A. Roggenkamp, A. Rakin, R. Zumbihl, L. Leitritz, and J. Heesemann. 1998. In vitro and in vivo expression studies of yopE from Yersinia enterocolitica using the gfp reporter gene. Mol. Microbiol. 30:865-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahl, B., M. Herrmann, A. S. Everding, H. G. Koch, K. Becker, E. Harms, R. A. Proctor, and G. Peters. 1998. Persistent infection with small colony variant strains of Staphylococcus aureus in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1023-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanner, B. I., and D. L. Gutnick. 1972. Use of neomycin in the isolation of mutants blocked in energy conservation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 111:287-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koebnik, R., K. P. Locher, and P. Van Gelder. 2000. Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: barrels in a nutshell. Mol. Microbiol. 37:239-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolle, W., and H. Hetsch. 1911. Die experimentelle Bakteriologie und die Infektionskrankheiten mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Immunitätslehre, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Urban und Schwarzenberg, Berlin, Germany.

- 17.Lee, B. C. 1995. Quelling the red menace: haem capture by bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 18:383-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis, L. A., D. Lewis, V. Persaud, S. Gopaul, and B. Turner. 1994. Transposition of IS2 into the hemB gene of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 176:2114-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis, L. A., K. Li, A. Gousse, F. Pereira, N. Pacheco, S. Pierre, P. Kodaman, and S. Lawson. 1991. Genetic and molecular analysis of spontaneous respiratory deficient (res−) mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiol. Immunol. 35:289-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahillon, J., and M. Chandler. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mey, A. R., and S. M. Payne. 2001. Haem utilization in Vibrio cholerae involves multiple TonB-dependent haem receptors. Mol. Microbiol. 42:835-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musher, D. M., R. E. Baughn, and G. L. Merrell. 1979. Selection of small-colony variants of Enterobacteriaceae by in vitro exposure to aminoglycosides: pathogenicity for experimental animals. J. Infect. Dis. 140:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ochsner, U. A., Z. Johnson, and M. L. Vasil. 2000. Genetics and regulation of two distinct haem-uptake systems, phu and has, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 146:185-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proctor, R. A. 1994. Microbial pathogenic factors: small colony variants, p. 79-90. In A. L. Bisno and F. A. Waldvogel (ed.), Infections associated with indwelling medical devices, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 25.Proctor, R. A., J. M. Balwit, and O. Vesga. 1994. Variant subpopulations of Staphylococcus aureus as cause of persistent and recurrent infections. Infect. Agents Dis. 3:302-312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Proctor, R. A., P. van Langevelde, M. Kristjansson, J. N. Maslow, and R. D. Arbeit. 1995. Persistent and relapsing infections associated with small-colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahn, A., J. Drummelsmith, and C. Whitfield. 1999. Conserved organization in the cps gene clusters for expression of Escherichia coli group 1 K antigens: relationship to the colanic acid biosynthesis locus and the cps genes from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 181:2307-2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roggenkamp, A., H. R. Neuberger, A. Flugel, T. Schmoll, and J. Heesemann. 1995. Substitution of two histidine residues in YadA protein of Yersinia enterocolitica abrogates collagen binding, cell adherence and mouse virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1207-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roggenkamp, A., A. Sing, M. Hornef, U. Brunner, I. B. Autenrieth, and J. Heesemann. 1998. Chronic prosthetic hip infection caused by a small-colony variant of Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2530-2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossi, M. S., J. D. Fetherston, S. Letoffe, E. Carniel, R. D. Perry, and J. M. Ghigo. 2001. Identification and characterization of the hemophore-dependent heme acquisition system of Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 69:6707-6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasarman, A., M. Surdeanu, A. Szegli, T. Horodniceanu, V. Greceanu, and A. Dumitrescu. 1968. Hemin-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 96:570-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang, Y. W., N. M. Ellis, M. K. Hopkins, D. H. Smith, D. E. Dodge, and D. H. Persing. 1998. Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic techniques for identification of unusual aerobic pathogenic gram-negative bacilli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3674-3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tardat, B., and D. Touati. 1991. Two global regulators repress the anaerobic expression of MnSOD in Escherichia coli::Fur (ferric uptake regulation) and Arc (aerobic respiration control). Mol. Microbiol. 5:455-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Eiff, C., C. Heilmann, R. A. Proctor, C. Woltz, G. Peters, and F. Gotz. 1997. A site-directed Staphylococcus aureus hemB mutant is a small-colony variant which persists intracellularly. J. Bacteriol. 179:4706-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng, M., B. Doan, T. D. Schneider, and G. Storz. 1999. OxyR and SoxRS regulation of fur. J. Bacteriol. 181:4639-4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziebuhr, W., C. Heilmann, F. Gotz, P. Meyer, K. Wilms, E. Straube, and J. Hacker. 1997. Detection of the intercellular adhesion gene cluster (ica) and phase variation in Staphylococcus epidermidis blood culture strains and mucosal isolates. Infect. Immun. 65:890-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]