Abstract

Reduced expression of the pro-apoptotic protein SMAC (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase) has been reported to correlate with cancer progression, while its significance and underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the role of SMAC in intestinal tumorigenesis using both human samples and animal models. Decreased SMAC expression was found to correlate with increased cIAP2 expression and higher grades of human colon cancer. In mice, SMAC deficiency significantly increased the incidence and size of colon tumors induced by azoxymethane (AOM)/dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS), and highly enriched β-catenin hot spot mutations. SMAC deficiency also significantly increased the incidence of spontaneous intestinal polyps in APCMin/+ mice. Loss of SMAC in mice led to elevated levels of cIAP1 and cIAP2, increased proliferation and activation of the NF-κB p65 subunit in normal and tumor tissues. Unexpectedly, SMAC deficiency had little effect on the incidence of precursor lesions, or apoptosis induced by AOM or DSS, or in established tumors in mice. Furthermore, SMAC knockout enhanced TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation via cIAP2 in HCT 116 colon cancer cells. These results demonstrate an essential and apoptosis-independent function of SMAC in tumor suppression and provide new insights into the biology and targeting of colon cancer.

Keywords: SMAC, cIAP, NF-κB, proliferation, colon cancer

INTRODUCTION

Second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase (SMAC), also known as direct inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP)-binding protein with low pI (Diablo), is a pro-apoptotic mitochondrial protein that is released into the cytosol in response to diverse apoptotic stimuli.1–3 Upon release into the cytosol, SMAC interacts with and antagonizes IAPs, such as XIAP, cIAP1 and cIAP2, through its N-terminal AVPI domain. This allows for caspase activation and subsequent cell death.1,2,4,5 SMAC appears to mediate apoptosis induced by selective classes of anticancer agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis inducing ligand in human cancer cells.1,6,7 Enhanced expression of SMAC and agents that mimic the AVPI domain of SMAC, also called SMAC mimetics or IAP antagonists, sensitizes human cancer cells to apoptosis induced by anticancer agents including TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand.7,8 However, induction of apoptosis is not affected by SMAC deficiency in response to various anticancer agents in murine models.9 A significant inverse correlation between SMAC expression and either the cancer stage or grade has been reported in renal cell carcinoma, lung cancer, testicular germ tumors, hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate,10 esophageal11 and colon cancer.12 However, the significance of SMAC in cancer progression is not well understood.10

Overexpression of IAP members, including XIAP, survivin and cIAP1/2, is found in many types of human cancer, and is associated with chemoresistance, disease progression and poor prognosis.13 The IAPs are best known for their ability to inhibit caspase activation and apoptosis.3 However, emerging evidence suggests that cIAP1 and cIAP2 have a crucial role in regulating canonical and non-canonical nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling in opposite directions.3 In the canonical NF-κB pathway, cIAP1 and cIAP2 regulate ubiquitin(Ub)-dependent activation of NF-κB downstream of TNFR1, which in turn drives the expression of genes important for inflammation, immunity, cell survival, cell migration and tumor development.3 Conversely, rapid degradation of cIAP1 and cIAP2 triggered by SMAC mimetics leads to activation of the non-conical NF-κβ pathway and TNFα secretion, which promotes apoptosis in certain cancer cells.14–17 IAP overexpression can result from gene amplification and chromosomal aberrations.3 Yet, whether IAP overexpression relates to reduced SMAC levels is still unclear.

In the current study we investigated the role of SMAC in intestinal tumorigenesis using human tumor samples, and two mouse models: azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS) (AOM/DSS)-induced colon cancer, and spontaneous intestinal tumors in APCMin/+ mice. We found that decreased SMAC expression correlates with progression of human colon cancer and increased cIAP2 expression. SMAC deficiency results in increased levels of cIAP1/2 in the intestinal mucosa and enhanced tumor development in both models. Surprisingly, loss of SMAC had little to no effect on apoptosis, but promoted proliferation and activation of NF-κB in the adjacent normal tissues as well as tumors in mice. Additionally, SMAC loss led to NF-κB activation via elevated cIAP2 levels and IkBα degradation in colon cancer cells. These data establish an apoptosis-independent function of SMAC in suppressing tumor progression, rather than tumor initiation.

RESULTS

SMAC expression was inversely correlated with the progression of human colon cancer

To determine a potential role of SMAC in colon cancer, we examined the expression of SMAC in colon cancer tissue arrays by immunohistochemistry (IHC). SMAC IHC confirmed the cytoplasmic expression of SMAC in normal as well as colon tumor cells (Figure 1a and Supplementary Figure S1A) as previously reported.12 Interestingly, compared with normal colon tissues, SMAC expression decreased during tumor progression in sex and age-matched patients (Figure 1b, Supplementary Figure S2, and Tables S1, S2 and S3). For example, 100% (17/17) of normal tissues had modest or high SMAC expression, while 14.8% (8/54) of Grade I, 20.2% (17/84) of Grade II, 39.0% (23/59) of Grade III and 65.4% (17/26) of Grade IV colon cancer tissues showed little to no SMAC expression (Figure 1b, Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S3). Notably, the intensity of SMAC expression also decreased as the tumor grade increased. Specifically, 10.2% (6/59) of Grade III and 0% (0/26) of Grade IV tumors expressed high levels (+ + and + + +) of SMAC compared with 24.1% (13/54) of Grade I and 34.5% (29/84) of Grade II tumors (Figure 1b and Supplementary Table S3). The specificity of human SMAC antibody was validated using isogenic SMAC knockout (KO)6 in IHC, and western blotting and control immunoglobin G in IHC (Supplementary Figures S1A and 7A). Analysis using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient indicated a significant negative correlation between SMAC expression and tumor grade (P<0.001) (Supplementary Figure S2). These results suggest that SMAC decreases during colon tumor development.

Figure 1.

SMAC and cIAP2 expression in human colon cancers. (a) Representative pictures of SMAC and cIAP2 staining (brown) in human colon tumors, magnification ×400 and ×200, respectively. (b) Quantification of expression of SMAC (left) and cIAP2 (right) in two human colon cancer TMAs. (c) Left, representative pictures of SMAC and cIAP2 staining (brown) in the grade IV stage human colon tumors on TMAs. Right, a scatter plot for the association between SMAC and cIAP2 staining in human colon tumors.

Decreased SMAC expression was correlated with increased cIAP2 expression in colon cancer progression

SMAC mimetics or overexpression downregulates cIAP l/2, but whether IAP levels are regulated by endogenous SMAC is not known.3 We therefore examined the expression of cIAP1 and cIAP2 by IHC in colon TMAs. IHC showed both cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of cIAP1 and cIAP2 proteins in cells (Figure 1a, and Supplementary Figures S1B, S1C, S2 and S3) as previously reported.18 Interestingly, cIAP2 expression increased during tumor progression (Figures 1a and b, Supplementary Figures S1B, S2, and Supplementary Tables S1 and S3). For example, none (0/17) of the normal tissues expressed modest or high levels (+ + and + + +) of cIAP2, whereas 17.9% (10/56) of Grade I, 43.2% (38/88) of Grade II, 79.7% (47/59) of Grade III and 81.6% (22/27) of Grade IV cancers did (Supplementary Table S3). Spearman’s analysis indicated both a significant positive correlation between cIAP2 expression and tumor grade (P<0.001) (Supplementary Figure S2), and an inverse correlation between cIAP2 and SMAC expression (P<0.01) (Figure 1c). Interestingly, this inverse correlation was highly significant in Grade III–IV tumors, but not in Grade I tumors (Supplementary Table S4). cIAP1 expression was not found to correlate with either grade or SMAC expression, which increased in early-stage colon tumors (Grade I) and gradually decreased in advanced tumors (Supplementary Figures S3B and C). Together, these results suggest an inverse correlation of SMAC and cIAP2 expression in human colon cancer development.

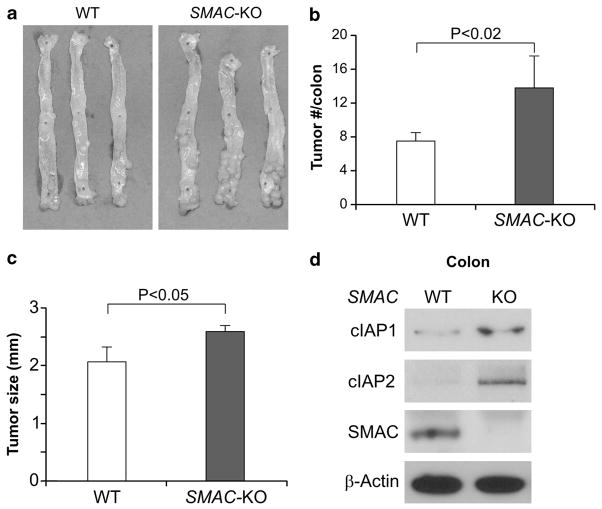

SMAC deficiency enhanced AOM/DSS-induced colon cancer in mice

The above observations prompted us to further investigate the role of SMAC in colon cancer using mouse models. Treatment of AOM followed by DSS induces colon cancer within 4 months in all C57BL/6 mice.19 We compared tumor incidence, size and grade in wild-type (WT) and SMAC KO littermates using this model (Figures 2a and b). Tumor incidence in SMAC KO mice increased by 84% compared with WT mice (13.8±3.7 vs 7.5±1.1), with the majority of tumors located in the middle and distal colon (Figures 2a and b). Additionally, the tumors found in SMAC KO mice were of larger size and higher grade (Figure 2c and Table 1). For instance, 60.0% of tumors in WT mice were adenomas with low-grade dysplasia (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S4A). This is in contrast to SMAC KO mice where 79.2% of tumors were adenomas with high-grade dysplasia (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S4A). Furthermore, SMAC deficiency resulted in elevated levels of both cIAP1 and cIAP2 in mouse colon (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

SMAC deficiency enhanced AOM/DSS-induced colon cancer in mice. (a) Representative pictures of AOM- and DSS-induced colon tumors in WT and SMAC KO mice. The colons from three mice with indicated genotypes were shown. (b) Quantification of colon tumor burden in WT and SMAC KO mice at 4 months. Values are means±s.d. (n =8 in each group). *P<0.001. (c) Quantification of tumor size in WT and SMAC KO mice. Values are means±s.d. (n =8 in each group). *P<0.05. (d) The levels of cIAP-1, cIAP-2 and SMAC in the colonic mucosa of WT and SMAC KO mice were analyzed by western blotting. β-Actin was used as the control for loading. Results from the pooled samples were shown (n =3 mice in each group).

Table 1.

Histological grades of AOM/DSS-induced colon tumors

| WT mice | SMAC KO mice |

|---|---|

| 3 LGD, 1 HGD | 10 HGD |

| 3 LGD, 2 HGD | 1 LGD, 8 HGD |

| 4 LGD, 1 HGD | 2 LGD, 7 HGD |

| 3 LGD, 2 HGD | 3 LGD, 6 HGD |

| 2 LGD, 3 HGD | 3 LGD, 5 HGD |

| 3 LGD, 3 HGD | 2 LGD, 6 HGD |

Abbreviations: LGD, adenoma with low grade dysplasia; HGD, adenoma with high grade dysplasia; SMAC KO, second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase gene knockout.

Aberrant crypt foci (ACF) have been reported as precursor lesions and a risk factor for colon cancer in both human and rodents, and can be induced by AOM treatment in mice.19,20 We therefore analyzed the incidence of AOM-induced ACF in WT and SMAC KO mice. Surprisingly, SMAC deficiency had no effect on ACF incidence (Supplementary Figure S4B). These results suggest that SMAC inhibits tumor progression, rather than tumor initiation.

SMAC deficiency enriched β-catenin mutations in AOM/DSS-induced colon tumors

Mutations in β-catenin lead to stabilization of β-catenin and increased signaling through the Tcf/Lef transcription factors.21 Frequent mutations in codons 32, 33, 34, 37 and 41 within the glycogen synthase kinase-3β phosphorylation motif have been reported in mouse and rat colon tumors induced by AOM or AOM/DSS.19,22 We sequenced exon 3 of β-catenin in tumors from WT and SMAC KO mice, and found that 44% (7/16) of tumors in WT mice had β-catenin mutations. Interestingly, 100% (19/19) of SMAC KO mice had mutations in all five codons (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S5A, P<0.001). Intense nuclear β-catenin staining, a marker for activation, was found in 3 of 12 (25%) tumors in WT mice, and 11 of 28 (39.3%) tumors in SMAC KO mice (Figure 3b and Supplementary Figure S5B). These data suggest that SMAC deficiency selectively cooperates with β-catenin mutations to promote colon cancer in AOM/DSS-treated mice.

Figure 3.

SMAC deficiency highly enriched β-catenin mutations in AOM/DSS-induced tumors. (a) The frequency of β-catenin exon 3 mutations in WT and SMAC KO mice (P<0.001). (b) Index of nuclear β-catenin of AOM/DSS-induced tumors in WT and SMAC KO mice.

SMAC deficiency did not affect apoptosis in tumors or colonic crypts following AOM or DSS treatment

To determine whether loss of SMAC is associated with reduced apoptosis, we analyzed size-matched tumors from WT and SMAC KO mice, but did not find a significant difference (Supplementary Figure S6A). Acute exposure to AOM or DSS is known to induce apoptosis in the colonic epithelium of mice.19,23,24 We then compared AOM-induced apoptosis in the colonic crypts of WT and SMAC KO mice at 8 h following treatment and found no significant difference (Supplementary Figure S7A). Additionally, no difference in apoptosis was detected in colonic crypts of WT or SMAC KO mice following DSS treatment (Supplementary Figure S7B). These results indicate that SMAC does not affect apoptosis in tumors or normal colonic crypts induced by either AOM or DSS.

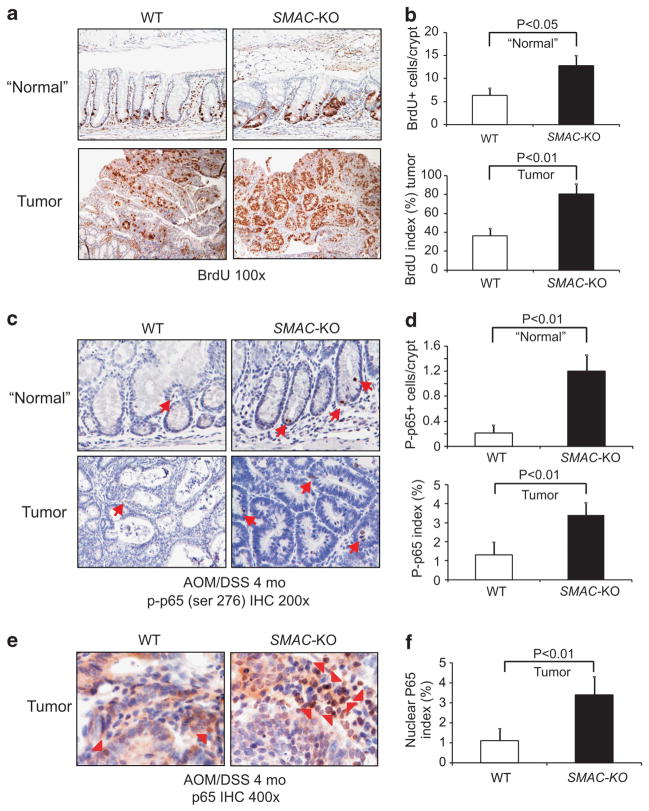

SMAC deficiency promoted proliferation and activation of p65 in AOM/DSS-induced colon tumors

We then analyzed proliferation in size-matched colon tumors from WT and SMAC KO mice by BrdU staining. The proliferation index significantly increased in adjacent ‘normal’ crypts as well as tumors of SMAC KO mice when compared with WT mice (Figures 4a and b). As cIAPs are required for TNFR1-mediated activation of NF-κB,3 and loss of SMAC resulted in increased cIAP1 and cIAP2 levels in the colonic mucosa (Figure 2d), we analyzed NF-κB activation by examining phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation of p65 in size-matched tumors. Interestingly, p-p65 increased significantly in both adjacent normal regions and tumors of SMAC KO mice compared with WT mice (Figures 4c and d and Supplementary Figure S8A). When compared with WT, SMAC KO mice also consistently showed a more than twofold increase in cells with nuclear p65 (Figures 4e and f, and Supplementary Figure S8B). These results suggest that loss of SMAC promotes proliferation, p65 activation and development of AOM/DSS-induced colon cancer.

Figure 4.

SMAC deficiency increased proliferation and NF-κB activation in the AOM/DSS-induced tumors. Tumors and adjacent normal tissues from WT and SMAC KO mice at 4 months of AOM/DSS treatment were analyzed for proliferation and p65 activation. (a) Representative pictures of BrdU (brown) incorporation in the “normal” crypts adjacent to tumors (top) and tumors (bottom). (b) Top, BrdU incorporation index was quantitated by counting 100 crypts per mouse. Bottom, BrdU incorporation index was quantitated by counting 100 cells per tumor. Values are means ±s.d., n =6 mice in each group. (c) Representative pictures of p-p65 (ser 276) in the ‘normal’ areas adjacent to tumors (top) and tumors (bottom), magnification, ×400. (d) Quantification of p-p65 (ser 276) in the ‘normal’ areas adjacent to tumors (top) and tumors (bottom). Values are means±s.d., n =4 mice in each group. (e) Representative pictures of total p65 in the tumors of WT and SMAC KO mice, magnification, ×400. Arrow heads indicate tumor cells with nuclear p65. (f) Quantification of nuclear p65 in the tumors of WT and SMAC KO mice. Values are means±s.d., n =4 mice in each group.

SMAC deficiency increased tumor formation in APCMin/+ mice

APCMin/+ mice develop multiple small intestinal polyps and recapitulate the prevalence of APC mutations in human colon cancer.25 We generated APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice to determine a potential role of SMAC in spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis. Sex- and age-matched cohorts of APCMin/+ and APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice were analyzed for tumor incidence at 4 months of age. APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice exhibited obvious weight loss (17.5±1.4 vs 25.6±1.1 g) (Supplementary Figure S9A) and developed significantly more macroadenomas (polyps) (67.4±9.3 vs 31.5±2.1) compared with APCMin/+ mice (Figure 5a and Supplementary Figure S9B). The increased incidence of macro-adenomas was found in all three portions of the small intestine, with a significant increase in large tumors (2–3 mm in diameter) (Figure 5b) compared with WT mice. However, the incidence of macrodenomas in the colon at 22 weeks of age or microadeno-mas19 of APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice at 4 weeks of age was not significantly different from that of APCMin/+ mice (Figures 5c and d). These data suggest SMAC deficiency preferentially enhances tumor progression in APCMin/+ mice.

Figure 5.

SMAC deficiency enhanced tumorigenesis in APCMin/+ mice. (a) Polyps in the colon (≥0.5 mm in diameter) were scored under stereoscope in age (22 weeks)- and sex-matched APCMin/+ and APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice. (b) Left, polyps in the small intestine stratified by anatomical regions. Right, the size distribution of polys in the small intestine. (c) Polyps in the colon were scored as in (a). (d) The number of microadenomas scored on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections in the small intestine and colon of mice at 4 weeks of age. n =5 in each group. Values are means±s.d. n =6 in each group in (a, b and c).

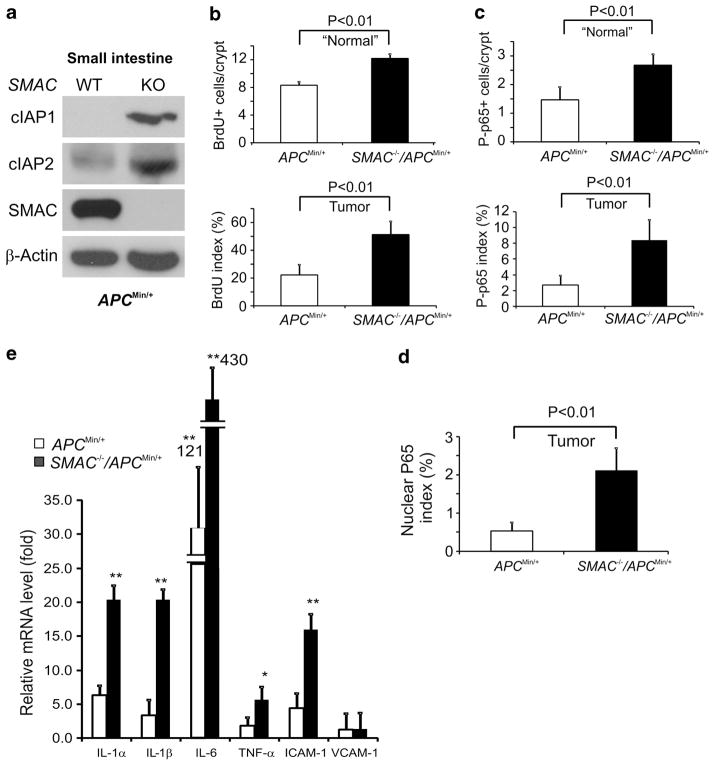

SMAC deficiency increased cIAP1 and cIAP2 expression, intestinal proliferation, and promoted p65 activation in APCMin/+ mice

To determine the potential roles of SMAC deficiency in enhancing spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis we compared cIAP1/2 levels, apoptosis, proliferation and p-p65 in APCMin/+ and APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice. Both cIAP1 and cIAP2 levels were significantly elevated in the intestinal mucosa of APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice (Figure 6a). However, no significant difference in apoptosis was found in size-matched tumors from these two groups of mice (Supplementary Figure S10A). Interestingly, the proliferation index and p-p65 levels significantly increased in both the adjacent normal and tumors of APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice. Consistently, over twofold more cells with nuclear p65 in these tumors were found (Figures 6b–d and Supplementary Figure S10B–E). Moreover, the levels of inflammatory cytokines, including several interleukins and TNF-α, were significantly elevated in the tumors from APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice compared with those from APCMin/+ mice (Figure 6d). Importantly, SMAC deficiency did not affect the serum levels of TNF-α (Supplementary Figure S10E), excluding the systemic inflammatory response as an explanation. These data suggest that loss of SMAC promotes proliferation of the intestinal epithelial cells likely through the activation of cIAP/NF-κB signaling in the tumor microenvironment to enhance tumor development in APCMin/+ mice.

Figure 6.

SMAC deficiency led to increased cIAPs, proliferation and p-p65 (ser 276) in intestinal crypts of APCMin/+ mice. (a) Levels of cIAP1, cIAP2, and SMAC in the small intestinal mucosa of 6–8-week old APCMin/+ and APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice were analyzed by western blotting. β-actin was used as the control for loading. Results from pooled samples were shown (n =3 mice in each group). (b) Quantification of BrdU incorporation index in the “normal” areas adjacent to tumors (top) and tumors (bottom) of APCMin/+ and APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice. Values are means±s.d., n =6 mice in each group. (c) Quantification of p-p65 (ser 276) in the ‘normal’ areas adjacent to tumors (top) and tumors (bottom) of APCMin/+ and APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice at 5 months old. Values are means ±s.d., n =4 mice in each group. Quantification was based on counting 100 crypts/mouse or 100 cells/tumor. (d) Quantification of nuclear p65 in the tumors from 5 month-old APCMin/+ or APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice. Values are means ±s.d., n =3 mice in each group. (e) Levels of various inflammatory cytokines in tumors from APCMin/+ or APCMin/+/SMAC KO mice were analyzed by RT–PCR. Values are means ±s.d., n =3 mice in each group. Levels in age-matched WT mice were defined as 1. *P<0.01 and **P<0.001.

SMAC deficiency promoted TNF-α-induced p65 activation through cIAP2 in human colon cancer cells

To directly probe the effect of SMAC loss on NF-κB signaling we examined p-p65, IkBα and cIAP1/2 levels in WT and SMAC KO HCT 116 colon cancer cells6 in response to TNFα treatment. Levels of cIAP1, cIAP2 l and p-p65 were significantly induced by TNFα in WT HCT116 cells, and increased further in SMAC KO cells (Figure 7a). Importantly, a more significant decrease of IkBα occurred in SMAC KO cells (Figure 7a). SMAC levels did not change in WT HCT 116 cells following TNFα treatment (Figure 7a). Using reporter assays, we found that NF-κB-mediated transcription following TNFα treatment was also significantly elevated in SMAC KO cells (Figure 7b). Knockdown of cIAP2, but not cIAP1, reduced TNFα-induced increase of p-p65 in SMAC KO cells (Figure 7c). Interestingly, depletion of cIAP1 knockdown led to elevated cIAP2 levels as expected,3 suggesting cIAP1 is not essential or rate-limiting for the activation of canonical NF-κB pathway by TNFα in these cells. These data strongly suggest that loss of SMAC in cancer cells leads to enhanced NF-κB activation in response to TNFα via cIAP2.

Figure 7.

SMAC deficiency increased TNF-α-induced p65 activation through cIAP2 in HCT116 cells. (a) Levels of indicated proteins in WT and SMAC KO HCT116 cells with or without 10 ng/ml TNFα treatment were analyzed by western blotting. β-Actin was used as the control for loading. (b) Relative p65 reporter activities were analyzed in the WT and SMAC KO HCT116 cells with or without 10 ng/ml TNFα treatment. (c) Levels of indicated proteins in WT and SMAC KO HCT116 cells treated with control (C), cIAP2 siRNA (CP2), or cIAP1 siRNA (CP1), with or without 10 ng/ml TNFα, were analyzed by western blotting. β-Actin was used as the control for loading. (d) A model for SMAC-mediated tumor suppression. Exposure to carcinogens or oncogenic mutations cooperate with TNFR1-mediated NF-κB signaling to promote tumor progression via enhance proliferation and a positive feedback loop. SMAC or SMAC mimetics keep the levels of cIAPs low to suppress this loop. It is conceivable (dashed line) that engagement of other death receptors, that is, Fas/CD95 sequesters cIAP1/2 to suppress NF-κB signaling and tumor progression, while their ablation promotes NF-κB activation and tumor progression independent of apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

Altered expression of SMAC or IAP is correlated with cancer progression and therapeutic resistance.3,10,12 Our studies demonstrated that SMAC selectively suppresses colon cancer progression by inhibiting cell proliferation and NF-κB activation, independent of apoptosis, and provides a potential mechanism of IAP overexpression in cancer. SMAC expression was shown to decrease during human colon cancer progression. Furthermore, loss of SMAC increased intestinal tumor formation induced by either carcinogens or loss of APC tumor suppressor gene, but had little or no effect on the incidence of precursor lesions. Finally, knockout of SMAC in colon cancer cells enhances TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation via cIAP2. These observations are novel and different for an established role of SMAC in promoting apoptosis in vivo26 and in cancer cells in response to selective agents, or that of SMAC mimetics or overexpression in blocking canonical NF-κB signaling by depleting both cIAP1 and cIAP2.3 To our knowledge, our work provides the first evidence that loss of endogenous SMAC is sufficient to promote NF-κB activation and tumorigenesis selectively via cIAP2, consistent with sensitization to SMAC mimetics upon cIAP2, but not cIAP1, knockdown in lung cancer cells.27 It is likely that factors other than SMAC contribute to elevated cIAP1 in colon and other cancers.

Apoptosis serves as a critical road block in transformation,28 and both p53-dependent and independent apoptosis inhibit intestinal tumorigenesis.19 Surprisingly, SMAC deficiency had little or no effect on colonic apoptosis induced by acute treatment of AOM or DSS, or in tumors induced by AOM/DSS or loss of APC. Instead, SMAC deficiency promoted proliferation in both the adjacent normal tissue and tumors. Therefore, the apoptotic function of SMAC does not have a critical role in tumor suppression in the colon. This is in line with earlier observations that SMAC deficiency does not promote spontaneous tumorigenesis, or cause resistance to apoptosis in murine models.9 While the mechanisms of SMAC downregulation in colon cancer remain largely unknown, our data indicate that loss of SMAC promotes intestinal tumor development independently of apoptosis.

Our data suggest that SMAC restricts cell proliferation and NF-κB activation in the intestinal epithelium through down-regulation of cIAP1/2. This mechanism appears to be critical in tumor suppression following exposure to carcinogens or mutations that activate stem cells, that is, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, but insufficient in WT or untreated mice (Figure 7d). Several possibilities may help explain increased tumor development in SMAC-deficient mice. cIAPs function as E3 ligases in TNFR1-mediated activation of NF-κB,3,29,30 and elevated cIAPs might contribute to tumor progression via increased NF-κB activation and cell proliferation.31 In addition, TNFα is abundant in tumor microenvironment and forms a positive feedback loop with NF-κB and TNFα in inflammation-associated cancer.24,32–36 Therefore, our model predicts that elevated cIAP levels amplify NF-κB signaling to promote tumor progression by cooperating with oncogenic mutations and proinflammatory cytokines (Figure 7d).

It is now widely accepted that death receptors can regulate NF-κB signaling.3,33 Two previous studies demonstrate apoptosis-independent functions of Fas/CD95 and Fas ligand in suppressing tumorigenesis in APCMin/+ mice.37,38 Loss of Fas or Fas L resulted in higher incidence of, and more invasive, cancer with enhanced proliferation and minimal change in apoptosis. Furthermore, cIAPs were reported to regulate Fas/CD95 signaling in a manner similar to TNFR1.39 Our study suggests an interesting possibility that loss of Fas/CD95 activates NF-κB signaling via a TNFR-1-dependent mechanism by releasing the downstream signaling molecules, and loss of SMAC potentially compromises Fas-mediated tumor suppression by sequestering such molecules (Figure 7d). Given the close interaction between intestinal epithelium and the immune system and the importance of NF-κB in both, a potential role of SMAC/IAPs in tumor microenvironment cannot be ruled out. Future studies utilizing tissue- or cell type-specific gene ablation or overexpression can help clarify their roles in colon cancer. Another rather surprising finding of our study is that SMAC deficiency selectively cooperates with β-catenin mutations clustered around the S33 residue. These findings suggest a potential crosstalk between death receptors and Wnt signaling in tumor progression, which is certainly worth exploring.

Altered expression of SMAC and IAP is found in various cancers.3,10,12 Our data further support the SMAC/IAP axis as potential targets in colon cancer. SMAC mimetics are currently in cancer trials, and have been found to be well tolerated, with minimal toxicity towards normal or primary cells.13,40,41 SMAC mimetics trigger auto-ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of cIAP1 and cIAP2, which results in activation of non-canonical NF-κB and assembly of TNFα-dependent death complex involving RIPK1/caspase 8 in cancer cells.14,42,43 Additionally, SMAC mimetics, as suggested by our work, might suppress tumor progression by inhibiting proliferation and the canonical NF-κB pathway (Figure 7d). Therefore, combination therapies involving SMAC mimetics may be a useful approach in patients with more advanced colon cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and treatment

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Pittsburgh. Detailed information on the generation of SMAC +/+, SMAC −/− (F6 on C57BL/6 background), APCMin/+ and APCMin/+/SMAC −/− mice has been previously described.26

AOM and DSS treatment

Methods were as previously described.19 In brief, 6–10-week-old littermates were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with a single dose of 12.5 mg/kg AOM (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). At 7 days post injection, mice were provided 2.5% DSS (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) in drinking water for 7 days, then followed by 14 days of regular water. This cycle was repeated twice. Following the final cycle, mice were given regular water for 2 months before killing. Some mice were injected i.p. with 100 mg/kg BrdU 2 h prior to killing to analyze crypt or tumor proliferation.

AOM treatment

The method was as previously described.19 For ACF formation, 6–10-week-old mice were injected i.p. with AOM (10 mg/kg) or saline (control) once a week for 6 weeks. Animals were then killed 4 weeks after the last AOM injection. To determine the level of apoptosis induction by AOM, mice were injected i.p. with 15 mg/kg AOM and killed 8 h later. BrdU (100 mg/kg) was i.p. injected into the mice 2 h prior to killing for analyzing crypt proliferation.

DSS treatment

The method was as previously described.19 Mice were given 2.5% DSS (MP Biomedicals) via drinking water. Mice received DSS treatment for either 1 or 3 days and then were immediately killed after treatment for analysis.

Analysis of protein and mRNA expression

Preparation of intestinal mucosa, scraping and isolation of DNA, total RNA and protein extracts from mouse tissues were performed and analyzed as previously described.44–46 Total protein extracts were analyzed by NuPage gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) electrophoresis, followed by western blotting. Primary antibodies used included those against human SMAC (IMG-248A, Imgenex, San Diego, CA, USA) for human tissue, mouse SMAC (gift from Dr Chunyin Du), cIAP1 (AF8181, R&D, Minneapolis, MN, USA), cIAP2 (AF8171, R&D), p-p65 (ser 276) (3037, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), p65 (#4764, Cell Signaling), β-catenin (C19220, Transduction Labs, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and β-actin (A5441, Sigma). Real-time RT–PCR was performed on a CFX96 Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with SYBR Green (Invitrogen) using previously described primers.24 Agarose (2%) gel electrophoresis was used to verify PCR products.

Tumor histology

Macroadenomas (>0.5 mm, polyps) induced by AOM/DSS were scored under a stereo microscope using fixed colons. Histology grading was done according to the established criteria using 5-μm hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections.19,47 Macroadenomas in APCMin/+ mice on the AIN93G diet (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA) were scored at 22 weeks as described above. The microadenomas in APCMin/+ mice were scored as previously described.19,45 ACF were identified in methylene blue-stained colons as previously described.19

Immunostaining

Mouse tissues and sections were prepared as described previously.19 Human colon tissue micro arrays (TMAs) CO208, CO2085a, CO1002 and T054a were purchased from US Biomax (Rockville, MD, USA). CO208 contains 60 cases of colon cancer and 9 cases of normal colon tissues, CO2085a contains 187 cases of colon cancer and 10 cases of normal colon tissues. Details on the staining of TMAs with antibodies and controls, as well as WT and SMAC KO HCT 116 cell blocks are found in Supplementary Material and Supplementary Table S1.

TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine-triphosphate nick end labeling) staining, BrdU, β-catenin p-p65 (ser 276) and total p65 IHC were performed on 5-μm sections of mouse tissues as previously described.19 For SMAC, cIAP1, cIAP2, p-p65 (ser 276) and total p65 immunohistochemical staining, slides were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the sections for 10 min in 0.1 M citrate buffer antigen retrieval solution (pH 6.0). After blocking with 20% goat or rabbit serum for 30 min, the sections were incubated with polyclonal anti-SMAC (IMG-248A, Imgenex), anti-cIAP1 (AF8181, R&D), anit-cIAP2 (AF8171, R&D), p-p65 (3037, Cell Signaling) and p65 (3987, Cell Signaling) antibody at 4°C overnight, at 1:50, 1:100, 1:200, 1:100 and 1:50 dilution, respectively. The control goat immunoglobin G (AB-108-C, R&D) and rabbit immunoglobin G (AB-105-C, R&D) were diluted as the same concentration as primary antibodies. Signal was detected using ABC and DAB kits (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). TUNEL or BrdU-positive cells were scored in 100 crypt sections and reported as mean±s.e.m. Three mice were used in each group.

IHC scoring criteria

The IHC signals were quantified visually. For SMAC, cytoplasmic staining was considered positive. For cIAP1 and cIAP2, both cytoplasmic and nuclear localization were considered positive. The staining is scored as − (0, no signal), + (1, weak signal), + + (2, moderate signal), + + + (3, strong staining) by two independent observers masked to patient outcome and stage, and a positive sample has at least 1% of cells with staining score ≥1.48

Mutational analysis of β-catenin

DNA isolation, PCR primers and conditions used for β-catenin exon 3 amplification and sequencing have been described.19

Cell culture and transfection

Colon cancer cell line HCT 116 was obtained from ATCC. The somatic knockout cell line HCT 116 SMAC KO has been described.6 Cell culture and transfection conditions, TNFα (R&D System) treatment, p65 reporter (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) assays and cIAP1/2 siRNA experiments are performed as described in Yu et al.49 and Wang et al.50 and details are found in Supplementary Material.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by the analysis of variance test (ANOVA), in which multiple comparisons were performed using the method of least significant difference. Data on the frequency of β-catenin mutations were analyzed by the χ2 test.19 The sex and age balance between patients with different tumor grades was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. The correlation between SMAC and cIAP2 expression and tumor grade was analyzed by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Differences were considered significant if the probability of the difference occurring by chance was less than 5 in 100 (P<0.05).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Monica E Buchanan, Matthew F Brown and other members of Zhang and Yu labs for helpful discussion and critical reading, and Laurice A Vance-Carr for editorial assistance. This work is supported in part by NIH grants CA129829, UO1-DK085570, American Cancer Society grant RGS-10-124-01-CCE and FAMRI (JY), NIH grants CA106348, CA121105, and American Cancer Society grant RSG-07-156-01-CNE (LZ). This project used the UPCI shared glassware, animal, and cell and tissue imaging facilities that were supported in part by award P30CA047904.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SMAC

second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases

- IAPs

inhibitors of apoptosis proteins

- BrdU

5-bromodeoxyuridine

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridinetriphosphate nick end labeling

- WT

wild type

- KO

knockout

- AOM

azoxymethane

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium salt

- ACF

aberrant crypt foci

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- GSK-3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

- TRAIL

tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions: WQ, HL, AS and QS performed the experiments and analyzed the data. HW analyzed the data. WQ, LZ and JY designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Du C, Fang M, Li Y, Li L, Wang X. Smac a mitochondrial protein that promotes cytochrome c-dependent caspase activation by eliminating IAP inhibition. Cell. 2000;102:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verhagen AM, Ekert PG, Pakusch M, Silke J, Connolly LM, Reid GE, et al. Identification of DIABLO, a mammalian protein that promotes apoptosis by binding to and antagonizing IAP proteins. Cell. 2000;102:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gyrd-Hansen M, Meier P. IAPs: from caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF-kappaB, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:561–574. doi: 10.1038/nrc2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu J, Wang P, Ming L, Wood MA, Zhang L. SMAC/Diablo mediates the pro-apoptotic function of PUMA by regulating PUMA-induced mitochondrial events. Oncogene. 2007;26:4189–4198. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Q, Zheng X, Zhang L, Yu J. Smac modulates chemosensitivity in head and neck cancer cells through the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2361–2372. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohli M, Yu J, Seaman C, Bardelli A, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, et al. SMAC/Diablo-dependent apoptosis induced by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in colon cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16897–16902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403405101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bank A, Wang P, Du C, Yu J, Zhang L. SMAC mimetics sensitize nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced apoptosis by promoting caspase-3-mediated cytochrome c release. Cancer Res. 2008;68:276–284. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fulda S, Wick W, Weller M, Debatin KM. Smac agonists sensitize for Apo2L/TRAIL-or anticancer drug-induced apoptosis and induce regression of malignant glioma in vivo. Nat Med. 2002;8:808–815. doi: 10.1038/nm735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada H, Suh WK, Jin J, Woo M, Du C, Elia A, et al. Generation and characterization of Smac/DIABLO-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3509–3517. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3509-3517.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Ruiz G, Maldonado V, Ceballos-Cancino G, Grajeda JP, Melendez-Zajgla J. Role of Smac/DIABLO in cancer progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:48. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, Zhou L, Huang J, Liu F, Yu J, Zhan Q, et al. Role of smac in determining the chemotherapeutic response of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5412–5422. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endo K, Kohnoe S, Watanabe A, Tashiro H, Sakata H, Morita M, et al. Clinical significance of Smac/DIABLO expression in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:351–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaCasse EC, Mahoney DJ, Cheung HH, Plenchette S, Baird S, Korneluk RG. IAP-targeted therapies for cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:6252–6275. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varfolomeev E, Blankenship JW, Wayson SM, Fedorova AV, Kayagaki N, Garg P, et al. IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-kappaB activation, and TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007;131:669–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaither A, Porter D, Yao Y, Borawski J, Yang G, Donovan J, et al. A Smac mimetic rescue screen reveals roles for inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11493–11498. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vince JE, Wong WW, Khan N, Feltham R, Chau D, Ahmed AU, et al. IAP antagonists target cIAP1 to induce TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007;131:682–693. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Du F, Wang X. TNF alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 2008;133:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krajewska M, Krajewski S, Banares S, Huang X, Turner B, Bubendorf L, et al. Elevated expression of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4914–4925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiu W, Carson-Walter EB, Kuan SF, Zhang L, Yu J. PUMA suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4999–5006. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens RG, Swede H, Rosenberg DW. Epidemiology of colonic aberrant crypt foci: review and analysis of existing studies. Cancer Lett. 2007;252:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi M, Nakatsugi S, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Frequent mutations of the beta-catenin gene in mouse colon tumors induced by azoxymethane. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1117–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirose Y, Yoshimi N, Makita H, Hara A, Tanaka T, Mori H. Early alterations of apoptosis and cell proliferation in azoxymethane-initiated rat colonic epithelium. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1996;87:575–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiu W, Wu B, Wang X, Buchanan ME, Regueiro MD, Hartman DJ, et al. PUMA-mediated intestinal epithelial apoptosis contributes to ulcerative colitis in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1722–1732. doi: 10.1172/JCI42917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu W, Wang X, Leibowitz B, Liu H, Barker N, Okada H, et al. Chemoprevention by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs eliminates oncogenic intestinal stem cells via SMAC-dependent apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20027–20032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010430107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen SL, Peyton M, Minna JD, Wang X. Overcoming cancer cell resistance to Smac mimetic induced apoptosis by modulating cIAP-2 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11936–11941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005667107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mace PD, Smits C, Vaux DL, Silke J, Day CL. Asymmetric recruitment of cIAPs by TRAF2. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conze DB, Albert L, Ferrick DA, Goeddel DV, Yeh WC, Mak T, et al. Posttranscriptional downregulation of c-IAP2 by the ubiquitin protein ligase c-IAP1 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3348–3356. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3348-3356.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, et al. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quante M, Wang TC. Inflammation and stem cells in gastrointestinal carcinogenesis. Physiology. 2008;23:350–359. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00031.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlantis K, Wullaert A, Sasaki Y, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky K, Roskams T, et al. Constitutive IKK2 activation in intestinal epithelial cells induces intestinal tumors in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2781–2793. doi: 10.1172/JCI45349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R. Regulation of spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis through the adaptor protein MyD88. Science. 2007;317:124–127. doi: 10.1126/science.1140488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popivanova BK, Kitamura K, Wu Y, Kondo T, Kagaya T, Kaneko S, et al. Blocking TNF-alpha in mice reduces colorectal carcinogenesis associated with chronic colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:560–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI32453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guillen-Ahlers H, Suckow MA, Castellino FJ, Ploplis VA. Fas/CD95 deficiency in ApcMin/+ mice increases intestinal tumor burden. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fingleton B, Carter KJ, Matrisian LM. Loss of functional Fas ligand enhances intestinal tumorigenesis in the Min mouse model. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4800–4806. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geserick P, Hupe M, Moulin M, Wong WW, Feoktistova M, Kellert B, et al. Cellular IAPs inhibit a cryptic CD95-induced cell death by limiting RIP1 kinase recruitment. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1037–1054. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu J, Zhang L. Apoptosis in human cancer cells. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:19–24. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leibowitz B, Yu J. Mitochondrial signaling in cell death via the Bcl-2 family. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:417–422. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.6.11392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertrand MJ, Milutinovic S, Dickson KM, Ho WC, Boudreault A, Durkin J, et al. cIAP1 and cIAP2 facilitate cancer cell survival by functioning as E3 ligases that promote RIP1 ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2008;30:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahoney DJ, Cheung HH, Mrad RL, Plenchette S, Simard C, Enwere E, et al. Both cIAP1 and cIAP2 regulate TNFalpha-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11778–11783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711122105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu B, Qiu W, Wang P, Yu H, Cheng T, Zambetti GP, et al. p53 independent induction of PUMA mediates intestinal apoptosis in response to ischaemia-reperfusion. Gut. 2007;56:645–654. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiu W, Carson-Walter EB, Liu H, Epperly M, Greenberger JS, Zambetti GP, et al. PUMA regulates intestinal progenitor cell radiosensitivity and gastrointestinal syndrome. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leibowitz BJ, Qiu W, Liu H, Cheng T, Zhang L, Yu J. Uncoupling p53 functions in radiation-induced intestinal damage via PUMA and p21. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:616–625. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boivin GP, Washington K, Yang K, Ward JM, Pretlow TP, Russell R, et al. Pathology of mouse models of intestinal cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:762–777. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yue W, Dacic S, Sun Q, Landreneau R, Guo M, Zhou W, et al. Frequent inactivation of RAMP2, EFEMP1 and Dutt1 in lung cancer by promoter hypermethylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4336–4344. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang P, Qiu W, Dudgeon C, Liu H, Huang C, Zambetti GP, et al. PUMA is directly activated by NF-kappaB and contributes to TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1192–1202. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.