Abstract

Leishmania spp. are protozoans that survive and replicate intracellularly in mammalian macrophages. Antileishmanial immunity requires gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-mediated macrophage activation and generation of microbicidal effector molecules. The presence of intracellular Leishmania sp. impairs macrophage responses to IFN-γ, which has led to the description of macrophages as deactivated. It has recently become apparent that in addition to classical activation, macrophages can be activated by distinct triggers to express noninflammatory or anti-inflammatory genes. These nonclassical activation programs have been called alternative or type II pathways. We hypothesized that during initial contact with a phagocyte, leishmaniae activate one of these nonclassical pathways, resulting in expression of genes whose products suppress microbicidal responses. Using DNA microarrays, we studied gene expression in RNAs from BALB/c bone marrow macrophages with and without Leishmania chagasi infection. Some changes were verified by an RNase protection assay, reverse transcription-PCR, immunoblotting, or a bioassay. The pattern of genes activated by leishmania phagocytosis differed from the pattern of genes activated by bacteria or lipopolysaccharide and IFN-γ. Genes encoding some proinflammatory cytokines, receptors, and Th1-type immune response genes were down-modulated, and some genes associated with anti-inflammatory or Th2-like immune responses were up-regulated. Nonetheless, some markers of alternative (arginase) or type II activation (interleukin-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha) were unchanged. These data suggest that macrophages infected with L. chagasi exhibit a hybrid activation profile that is more characteristic of alternative or type II activation than of classical activation but does not strictly fall into either of these categories. We speculate that the pattern of genes upregulated by leishmania phagocytosis optimizes the chance of parasite survival in this hostile environment.

Leishmania spp. are parasitic protozoans with a two life stages that correspond to the transit of the organisms between two hosts. The extracellular promastigote is found in the gut of the sand fly vector, and the obligate intracellular amastigote resides in the mammalian host macrophage. During a blood meal the sand fly inoculates the promastigote into a pool of blood in the skin, where it is phagocytosed by a resident mononuclear phagocyte. Inside the macrophage the parasite changes to an amastigote, which is the obligate intracellular form and the only form of the parasite found in a mammalian host. Intracellular parasites spread to other mononuclear phagocytes of the reticuloendothelial system and cause a spectrum of diseases ranging from a self-limiting cutaneous disease to potentially fatal visceral leishmaniasis (50).

Leishmania spp. survive and replicate inside mammalian macrophages, a hostile environment that is lethal to other microbes (7). Paradoxically, leishmaniae are killed by exposure in vitro to the oxidative effector molecules generated by macrophages. In addition, both human and murine macrophages can be activated by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) to kill intracellular Leishmania donovani (42, 47). However, it has also been documented that macrophages infected with Leishmania spp. are defective in their responses to IFN-γ, which has led to description of these macrophages as deactivated (20, 34, 44, 45, 49, 56). These seemingly conflicting reports may reflect the effects that the intracellular parasite has on macrophage gene expression and competition between these effects and microbicidal activities of the macrophage. Until recently, it was not technically feasible to analyze the spectrum of genes modulated when a pathogen enters a host cell. The advent of oligonucleotide arrays has now made it possible to examine the steady-state levels of thousands of genes in a single experiment. Matlashewski and Buates were the first workers to characterize which of a large number of macrophage genes were modulated by leishmania infection, in a study of 588 genes expressed by mouse macrophages after 4 days of infection with L. donovani amastigotes (38). The data of these researchers showed that expression of 37% of the genes analyzed was down-modulated approximately twofold in infected macrophages compared to the expression in uninfected macrophages. In contrast, only eight of the mRNAs studied were up-regulated during L. donovani infection, supporting the notion that there is macrophage deactivation. In a quite different study, Chaussabel et al. (10) analyzed the expression of 12,000 genes in human dendritic cells and human macrophages infected for 16 h with Leishmania major or L. donovani. The data of these authors indicated that Leishmania spp. were not good inducers of proinflammatory gene expression in human macrophages. Interestingly, similar numbers of mRNAs were down- or up-regulated, in contrast to the study of Matlashewski and Buates in which longer-term infection was examined. These data argue against the hypothesis that there is general suppression of gene activation that arises acutely at the time of leishmania phagocytosis by human macrophages.

Resident tissue macrophages undergo local activation in response to various inflammatory and immune stimuli (27). In IFN-γ-primed macrophages, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces classical activation, which is characterized by activation of an array of proinflammatory molecules, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), as well as induction of an oxidative burst and production of NȮ through the action of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). It has now become apparent that macrophages can also be activated by certain stimuli to express anti-inflammatory molecules, which results in a state that has been called alternative activation (25, 27, 31, 40). Further complicating matters, a state of macrophage activation that differs from both classical activation and alternative activation has been described as type II activation (2, 40). In the present study we began with the hypothesis that phagocytosis of leishmania activates a program of genes in the macrophage corresponding to either the alternative phenotype or the type II phenotype, resulting in expression of genes whose products suppress inflammation. Our model system was BALB/c bone marrow macrophages infected with Leishmania chagasi, the causative agent of visceral leishmaniasis in the Americas. The steady-state abundance of RNA from the infected macrophages was analyzed by using an Affymetrix DNA microchip. Our results suggested that macrophages infected with L. chagasi down-modulate expression of many proinflammatory genes, whereas they up-regulate expression of several genes implicated in anti-inflammatory responses, with some but not all characteristics of alternative or type II activation. The data suggest that L. chagasi infection promotes a state of nonclassical activation in macrophages, which promotes an anti-inflammatory environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

A Brazilian strain of L. chagasi (MHOM/BR/00/1669) was maintained by serial passage in male Syrian hamsters as described previously (68). Promastigotes grown in hemoflagellate modified minimal essential medium were used in the stationary phase of growth for all experiments.

Bone marrow macrophage infection and RNA harvest.

Bone marrow cells from BALB/c mouse long bones were cultured at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 in RPMI-based macrophage culture medium with 10% fetal calf serum (RP-10) (10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1% l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml in RPMI [GIBCO, Carlsbad, Calif.]) containing 20% L929 cell culture supernatant (American Tissue Type Collection, Manassas, Va.) as a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor. After 7 to 9 days, differentiated adherent macrophages were detached from the plate with a solution containing 2.5 mg of trypsin per ml and 1 mM EDTA (GIBCO) (12). A total of 12 × 106 macrophages were cultured in petri dishes in RP-10 without L929 medium for an additional 48 h prior to infection. A total of 5 × 105 macrophages were allowed to adhere to coverslips in 24-well plates to determine the levels of infection microscopically at several times after infection. Stationary-phase L. chagasi promastigotes were opsonized by incubation in 5% fresh serum from C5-deficient A/J mice in Hanks balanced salt solution for 30 min at 37°C and added to some macrophage cultures at a multiplicity of infection of 5:1. The infection was synchronized by centrifugation of the plates for 3 min at 330 × g. Promastigotes were removed by rinsing after 1 h of infection, and cells were then incubated in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Then 1, 4, and 24 h after addition of promastigotes, RNA was harvested from replicate infected or uninfected wells by using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, Tex.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The times were chosen because of preliminary RNase protection assays which showed that that the levels of some transcripts (macrophage inflammatory protein 1α [MIP-1α], MIP-1β) increased by 30 min and peaked 4 h after exposure of macrophages to IFN-γ and LPS, whereas the levels of other transcripts (IL-1Ra) peaked after 24 h. Early and late times were therefore included in order to not miss important changes in transcript abundance. RNA concentrations were measured with a Beckman DU 530 spectrophotometer.

Microarray methodology.

Microarray analyses were performed by using Affymetrix chips as recommended by the manufacturer. Contaminating DNA was removed from total macrophage RNA by using 1 U of DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) per μg of RNA, and this was followed by purification with RNeasy (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Ten micrograms of total RNA was used for microarray analyses. Briefly, cDNA was synthesized from total RNA [with BRL Superscript T7-(dT)24 primer], and this was followed by an in vitro transcription reaction with biotinylated UTP-CTP (ENZO kit; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, Calif.). The cRNA was fragmented to obtain 50- to 100-mers by using a high salt concentration and heat. cRNA samples were first hybridized to a test chip (Affymetrix) containing target sequences from the 5′, middle, and 3′ coding regions of several housekeeping genes (including the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH] and β-actin genes) to evaluate the quality. Once the test chip confirmed that full-length products were represented, the remainder of the cRNA was hybridized overnight to the murine genome MG-U74 A DNA chip from Affymetrix. This chip contains oligonucleotides representing functionally characterized (known) sequences from the Mouse UniGene database (build 74; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene). In addition, public data sources, such as GenBank, were used to design oligonucleotide sequences on arrays. A draft assembly of the genome was used to assess the sequence orientation and quality. Approximately 6,000 expressed sequence tags, also included in the Affymetrix MG-U74 A chip, were derived from the same UniGene build. Two other chips in the murine Affymetrix set (not used in this study) included the additional unknown murine expressed sequence tags from UniGene build 74. Each transcript was represented by 16 pairs of probes, including one perfectly matched probe and another probe with a mismatched base. Further details of the chip design can be found at the www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/technotesmain.affx website.

DNA chips were hybridized with 15 μg of fragmented cRNA in a hybridization mixture that included control oligonucleotide B2 designed by Affymetrix, 0.1 mg of herring sperm DNA per ml, 0.5 mg of acetlyated bovine serum albumin per ml, and 1× MES hybridization buffer (50 mM MES [2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid monohydrate], 0.5 M [Na+], 10 mM EDTA, 0.005% Tween 20). The control oligonucleotide B2 hybridized to structural segments of the chip, which allowed proper scanning and grid alignment. The hybridization cocktail was heated to 95°C and then hybridized to a Test3 gene chip array at 45°C for 16 h. The remainder of the cocktail was stored at −20°C for subsequent hybridization to the MG-U74 A chip by using a method similar to the method used for test chip hybridization.

After hybridization, the chip was washed and stained with streptavidin-phycoerythrin. By monitoring the fluorescence associated with each DNA location, it was possible to infer the abundance of each mRNA in the sample. The relative fluorescence of the mismatched probe was subtracted from that of the perfect match. Chips were scanned twice and analyzed first for the presence or absence of transcripts. The hybridization intensities in chips prepared for different conditions were compared to determine whether the level of a particular transcript was induced, decreased, or not changed compared to the level of the baseline (uninfected macrophage) control. Analyses were performed by using the Affymetrix software and were exported in Excel spreadsheet format.

Microarray data analysis.

The sample integrity and hybridization performance were assessed by hybridization to sets of spiked and endogenous controls [bioB, bioC, bioD, cre; poly(A)-diaminopimelic acid, Lys, Phe, Thr, and Trp; control actin, GAPDH, and hexokinase genes]. The fluorescence intensities of controls and cRNAs were monitored by using Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5 software, which evaluated the fluorescence signal elicited by each probe set to determine whether a transcript was present, absent, or marginal. The algorithm identified and removed the contributions of stray hybridization signals, and it estimated the relative abundance of each transcript. The data were analyzed by comparison of two arrays, which generated a qualitative output with an associated Affymetrix P value and a quantitative measure with a confidence interval. The qualitative output indicated whether a transcript was increased, decreased, or equivalent compared to the baseline. The quantitative measure provided an estimate of the relative difference in transcript abundance between the two arrays.

The Affymetrix Data Mining Tool was used to filter and sort the combined data sets from replicate samples and multiple arrays (www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/technotesmain.affx). This tool contains clustering algorithms to group together samples or genes with similar expression patterns. These algorithms start with sequence clusters in UniGene and functional StackPACK cluster assemblies in Electric Genetics (http://www.egenetics.com/stackpack.html). For this analysis, transcript sets were generated by querying gene groups that were modulated during L. chagasi infection. The cutoff to determine whether the level of a gene increased or decreased was a twofold difference between the fluorescence signal intensity from a noninfected control and the fluorescence signal intensity from an L. chagasi-infected macrophage.

RT-PCR and RNase protection assays.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and RNase protection assays were performed to corroborate some microarray results. Either 18S rRNA, L32, or GAPDH transcripts were used as loading controls. Primers were designed to cross intron-exon boundaries. The RT-PCR primers were 18S rRNA sense (5′-TCA AGA ACG AAA GTC GGA GG-3′), 18S rRNA antisense (5′-GGA CAT CTA AGG GCA TCA CA-3′), caveolin-1 sense (5′-ACG TGG TCA AGA TTG ACT TTG AA-3′), caveolin-1 antisense (5′-GCA GTA GCT TAG AAG AGA CAA G-3′), androgen receptor sense (5′-TCT CAA GAG TTT GGA TGG CTC C-3′), and androgen receptor antisense (5′-GAG ATG ATC TCT GCC ATC ATT TC-3′) (5). All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, Iowa). RT-PCRs were performed by using One Step RT-PCR kits (Qiagen). Reaction products were analyzed in 0.6% agarose gels, and densitometry analysis was performed with a CP700D Mitsubishi densitometer.

For RNase protection assays, total RNA was hybridized to MCK-2B templates or custom templates manufactured by PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.). [32P]RNA probes were synthesized and RNase protection assays were performed by using kits from PharMingen according to the manufacturer's instructions. The hybridized samples were separated on 5% acrylamide gels and exposed to Kodak X-OMAT AR film, followed by densitometry. The band densities corresponding to the transcripts tested were normalized to the densities of the L32 and GAPDH internal control transcripts for each sample.

Arginase activity assays.

Arginase activity in bone marrow macrophages was measured as the percentage of conversion of [14C]arginine to [14C]urea and ornithine for 48 h of culture as described previously (14, 61). Briefly, 0.25 μM l-[guanido-14C]arginine was added to 1 × 105 bone marrow macrophages in 200 μl in 96-well plates, with or without promastigotes at a ratio of 5:1. Then 20 ng of recombinant murine IL-4 (R&D Systems) per ml was added to some wells as a positive control. After incubation for 48 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2, 0.8 ml of 250 mM acetic acid-100 mM urea-10 mM l-arginine (pH 4.5) was added to 150 μl of culture supernatant. The nonmetabolized [14C]arginine in supernatants was precipitated with Dowex resin (Sigma), and the soluble [14C]urea in 0.5 ml of solution was counted with a scintillation counter. The percentage of conversion of [14C]arginine was calculated as follows:

|

where 0.36 is a correction factor for volume dilutions made in the assay.

Immunoblotting.

Total protein was harvested from uninfected or infected macrophages 24 and 48 h after infection. Proteins from 1.2 × 106 cells were separated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose (35). After blocking, immunoblots were incubated with 1:500 polyclonal rabbit antiserum against the androgen receptor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.), 1:1,000 mouse anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (Oncogene, San Diego, Calif.), 1:1,000 goat anti-caveolin-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), or 1:20,000 rabbit polyclonal anti-β-actin (ABCAM; http://www.abcam.com/). Incubation with primary antibody was followed by incubation with 1:10,000 secondary peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Jackson Immunoresearch), peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (Jackson), or peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.). Blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.).

RESULTS

Changes in average levels of mRNAs upon leishmania infection.

Pooled bone marrow macrophages from 10 BALB/c mice were infected with serum-opsonized L. chagasi promastigotes for 1, 4, or 24 h. Opsonization was performed with C5-deficient A/J mouse serum to avoid disruption of the parasite membranes. To ensure that a majority of the macrophages were infected, conditions were optimized so that the initial infection levels were ≥75%. The degrees of infection at various times during infection are shown in Table 1. Most parasites remained oblong and promastigote-like at 4 h. The transition to small oval or round amastigote-like forms began at 24 h and was complete by 48 h. As reported previously, many parasites were killed during the first few days of bone marrow macrophage infection (23).

TABLE 1.

Intracellular survival of L. chagasi in bone marrow macrophages used for microarray experiments

| Array | % Infection (no. of parasites/100 macrophages) at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | |

| 1 | 75 (325) | 68 (253) | 61 (177) | |

| 2 | 83 (261) | 74 (205) | 55 (120) | 46 (87) |

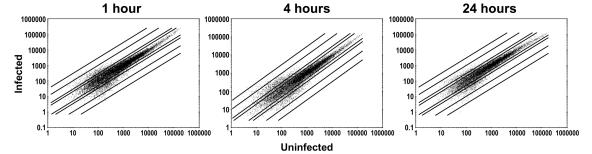

Total RNA from infected or control uninfected macrophages was used to generate cRNA, which was followed by hybridization to replicate Affymetrix MG-U74 A DNA chips. Overall changes in the abundance of mRNAs are summarized in Fig. 1, Table 2, and the table found at http://www.int-med.uiowa.edu/research/wilsonm/Table2.htm. For the 12,488 transcripts on the DNA chip, the steady-state levels of most mRNAs in infected macrophages were less than twofold different from the steady-state levels of the corresponding mRNAs in uninfected macrophages (77.8% of the transcripts were unchanged after 1 h of infection, 77.9% were unchanged after 4 h, and 81.8% were unchanged after 24 h). The mean variation in the absolute fluorescence values for the two replicate uninfected macrophage samples was 20.47%. The scatter plots in Fig. 1 show that the majority of cRNAs from infected (y axis) versus uninfected (x axis) macrophages generated hybridization signals between 0.5 and 2.0, indicating that there was a less-than-twofold change in either direction. When only the mRNAs whose levels changed more than twofold compared with the levels in the controls were considered, there were more increases in transcript abundance at 4 h than at the two other times. In contrast, the levels of more transcripts were decreased at 1 or 24 h after infection than at 4 h after infection (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Overall changes in mRNA levels during infection. Murine bone marrow macrophages were infected with stationary-phase L. chagasi promastigotes, and mRNA was isolated from replicate cultures after 1, 4, or 24 h. After generation of cRNA and hybridization to Affymetrix chips, the normalized intensities of hybridization in uninfected and infected cultures were compared. In scatter plots on a log scale, each of the 12,488 transcripts on the chip is represented by a single dot corresponding to the intensity of hybridization of cRNA from uninfected macrophages to the chips (x axis) versus the intensity of hybridization of cRNA from infected macrophages to the chips (y axis). The units are arbitrary. Dots that lie between the lines represent transcripts whose signal intensities changed less than twofold after infection. The lines extending in either direction outward represent transcripts with 2-fold, 10-fold, and 30-fold changes in fluorescence intensity. Dots falling above and to the left of lines represent transcripts whose hybridization intensities were greater in infected macrophages than in uninfected macrophages, whereas dots falling below and to the right of lines represent transcripts whose hybridization intensities were less in infected macrophages than in uninfected macrophages.

TABLE 2.

Transcripts that changed after phagocytosis of L. chagasi promastigotes

| Change | 1 ha

|

4 h

|

24 h

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. changedb | % Changedc | No. changed | % Changed | No. changed | % Changed | |

| Decreased ≤0.1 fold | 128 | 1.02 | 82 | 0.66 | 91 | 0.73 |

| Decreased ≤0.2 fold | 409 | 3.28 | 286 | 2.29 | 297 | 2.38 |

| Decreased ≤0.5 fold | 1,633 | 13.08 | 1,171 | 9.38 | 1,383 | 11.07 |

| Increased ≥2-fold | 1,134 | 9.08 | 1,584 | 12.7 | 891 | 7.13 |

| Increased ≥5-fold | 122 | 0.98 | 325 | 2.6 | 70 | 0.56 |

| Increased ≥10-fold | 18 | 0.14 | 61 | 0.49 | 7 | 0.06 |

| Increased ≥20-fold | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0.10 | 0 | 0 |

Time after infection was initiated.

Absolute number of mRNAs that were different in infected macrophages compared to uninfected macrophages.

Percentage of transcripts that changed.

Changes in specific transcripts on microarrays.

By using the data-mining tools provided by Affymetrix, L. chagasi infection was found to result in changes in the levels of transcripts in different functional groups. Infection-induced changes in some transcripts of interest to leishmania phagocytosis are shown in the table at the http://www.int-med.uiowa.edu/research/WilsonM/Table2.htm website. This table shows changes observed at all times after infection; Affymetrix codes for transcript pairs are shown for ease of comparison with other studies. Table 3 shows the 20 transcripts showing the greatest increases and the 20 transcripts showing the greatest decreases at the different times after infection. In each case a change in gene expression was calculated by determining the ratio of fluorescence intensity (degree of hybridization) corresponding to a gene in cRNA from infected macrophages to the mean fluorescence intensity for the same gene in cRNA from two replicate uninfected macrophage samples. Data are shown only for changes in transcripts that were consistently observed in both replicate microarray experiments. Expressed sequence tags were not included in these tables.

TABLE 3.

Transcripts with the greatest changes at each time point (excluding expressed sequence tags)

| Time (h) | Increase

|

Decrease

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold | Description | Fold | Description | |

| 1 | 13.42 | Enabled homolog (Drosophila) | 0.03 | Sterol-C5-desaturase |

| 12.97 | Disintegrin metalloprotease (decysin gene) | 0.04 | CPETR2 (Cpetr2) | |

| 12.31 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 8 | 0.04 | BMP-4 gene | |

| 12.27 | 5-HT1c receptor | 0.07 | Salivary protein 1 | |

| 12.27 | AREC3 | 0.07 | Cannabinoid receptor 2 (macrophage) | |

| 10.91 | Murine retrovirus readthrough RNA | 0.08 | Phenylalanine hydroxylase | |

| 10.70 | Dermatan sulfate proteoglycan 3 | 0.08 | Protease-activated receptor 3 | |

| 10.20 | AMY-1 | 0.09 | Fused toes | |

| 9.59 | Cyritestin 1 | 0.10 | Adenosine kinase | |

| 8.94 | Keratin complex 2, gene 17 | 0.10 | Testis 14-3-3 protein theta-subtype | |

| 8.90 | Developmentally regulated repeat (Dr-3) | 0.10 | Potential grb2- and fyn-binding protein | |

| 8.88 | Calcitonin receptor | 0.10 | Chromogranin B | |

| 8.88 | Neurexophilin 2 (Nxph-2) | 0.11 | Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-3, delta™-3-beta | |

| 8.84 | IL-6 | 0.11 | Matrix metalloproteinase 3 | |

| 8.08 | Vesl-1L | 0.11 | Protein encoded by methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 | |

| 7.82 | Ephrin A5 | 0.11 | Leptin receptor | |

| 7.82 | Myoglobin | 0.11 | Zinc finger protein 96 (Zfp96) | |

| 7.42 | Membrane cofactor protein | 0.11 | T-cell receptor beta-chain mRNA, VDJ region | |

| 7.07 | CD44 | 0.11 | Transformed mouse 3T3 cell double minute | |

| 6.93 | Phenol sulfotransferase | 0.12 | Tektin | |

| 4 | 22.84 | Alpha-tubulin isotype M-alpha-3 | 0.06 | Crystallin, gamma B |

| 22.37 | AMY-1 | 0.07 | Erythroid alpha-spectrin (Spna 1) | |

| 16.43 | Granzyme E | 0.07 | Dihydrofolate reductase | |

| 14.65 | Transcription factor A, mitochondrial | 0.08 | Tumor necrosis factor induced protein 3 | |

| 13.79 | Fibroblast-inducible secreted protein | 0.09 | A12 | |

| 12.87 | Zinc finger protein | 0.09 | Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK2L), 39-kDa CDK2 variant | |

| 12.76 | Caspase 12 | 0.09 | 3-OH-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase | |

| 12.73 | Kallikrein-binding protein | 0.10 | Budding inhibited by benzimidazoles homolog | |

| 12.68 | Intestinal tyrosine kinase | 0.10 | P glycoprotein 3 | |

| 12.63 | Coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor-like 1 | 0.10 | Nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 2 | |

| 12.35 | ISBT | 0.11 | Anti-DNA immunoglobulin light chain immunoglobulin M | |

| 12.14 | Nidogen | 0.11 | Alpha 1A-adrenergic receptor | |

| 12.00 | mRNA expressed in renal proximal tubles | 0.11 | GABA-A receptor subunit alpha 6 | |

| 11.52 | Desmocollin 2 | 0.11 | Caspase 7 | |

| 11.47 | Epsilon-casein | 0.11 | Deubiquitinating enzyme 2 | |

| 11.00 | TGF-α | 0.11 | Alpha-1,3-fucosyltransferase IX | |

| 10.70 | TGF-β receptor II | 0.11 | Transcription factor L-Sox5 | |

| 10.49 | Guanylin mRNA | 0.12 | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 8 | |

| 10.36 | Inhibitor protein of cAMP-dependent protein kinase | 0.12 | Angiopoietin-1 | |

| 9.85 | Lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 | 0.13 | Putative transcriptional regulator (MmTbx14) | |

| 24 | 12.87 | EYA4 protein | 0.06 | IL-4 |

| 12.02 | Hus1-like protein (Hus1) | 0.06 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2 family, member 5 | |

| 10.03 | Calcium binding protein D-9k | 0.07 | DNA segment, Chr 6, human | |

| 8.87 | Transferrin receptor | 0.07 | Pax9 | |

| 8.86 | YE1/48 | 0.07 | T-cell receptor beta-chain mRNA, VDJ region | |

| 8.75 | Potassium inwardly rectifying channel J12 | 0.09 | Stromelysin-2 | |

| 7.85 | Retinal pigment rhodopsin homolog | 0.09 | Fused toes | |

| 7.68 | Osteomodulin | 0.09 | AC133 antigen homolog | |

| 7.42 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 8 | 0.10 | Kinesin heavy chain | |

| 7.23 | Putative pheromone receptor (VR8) | 0.10 | Disintegrin and metalloprotease+thrombospondin motifs | |

| 7.03 | CF membrane conductance regulator homolog | 0.10 | N-Acetylgalactosaminyltransferase | |

| 6.36 | Retina and anterior neural fold homeobox | 0.11 | Growth factor-independent 1B | |

| 6.34 | gag-related peptide | 0.11 | Elastin | |

| 6.05 | Kinesin heavy chain member 1A | 0.11 | Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 2 | |

| 6.01 | IFN-β | 0.11 | Pleiotrophin | |

| 5.99 | Link protein | 0.11 | Disintegrin and metalloprotease domain (ADAM) 5 | |

| 5.99 | Disintegrin metalloprotease domain (ADAM) 7 | 0.11 | Calpain-like protease | |

| 5.86 | Neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor type 3 | 0.12 | Integrin binding sialoprotein | |

| 5.85 | Vitamin D receptor | 0.13 | Pericentriolar material 1 (Pcm1) | |

| 5.73 | Phenol sulfotransferase mRNA | 0.13 | Major urinary protein 2 | |

Proinflammatory molecules and chemokines.

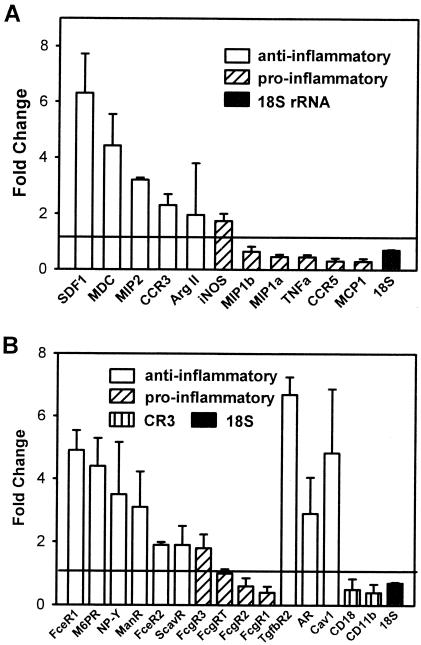

The data are remarkable because of the lack of induction of mRNAs associated with a proinflammatory response. This is in contrast to the response to the changes in macrophage gene expression induced by phagocytosis of bacterial pathogens, as documented in several previously described microarray experiments (8, 11, 18, 43, 48, 59, 60, 62, 66). Figure 2 shows the changes (means ± standard deviations) in the levels of mRNAs encoding some chemokines, chemokine receptors, or phagocytic receptors 4 h after L. chagasi infection. The data represent the means of two separate experiments performed with different harvests of infected or uninfected pooled BALB/c bone marrow macrophages, different hamster isolates of L. chagasi, and replicate chips for uninfected macrophages. Transcripts associated with proinflammatory or Th1-type immune responses and transcripts associated with anti-inflammatory or Th2-type immune responses are indicated in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Changes in the levels of some selected macrophage transcripts associated with pro- or anti-inflammatory responses induced by L. chagasi phagocytosis. The data indicate the fold changes (means ± standard deviations) in fluorescence intensities for selected transcripts in infected macrophages compared to the fluorescence intensities for the transcripts in noninfected macrophages. A ratio of 1.0, indicated by the horizontal line, indicates that there was no change upon infection. The data were derived from two separate microarray experiments; in each experiment we used pooled bone marrow macrophages derived from 10 individual mice. Two control samples (uninfected macrophages) were individually hybridized. (A) mRNAs encoding chemokines, chemokine receptors, and some antimicrobial proteins. Ratios are shown for some transcripts whose levels changed significantly after 4 h of L. chagasi infection. Transcripts that have been associated with classical macrophage activation or a Th1-type response are indicated by bars with diagonal stripes. Transcripts implicated in alternative activation or Th2-type immune responses are indicated by open bars. The control 18S rRNA is indicated by a solid bar. The timing of the increase in the level of MIP-2 mRNA was different in different experiments; the data shown are the mean for the hybridization intensity at 4 h of infection in the first experiment and the hybridization intensity at 1 h of infection in the second experiment. (B) Steady-state levels of mRNAs encoding some phagocytosis receptors involved in classical (striped bars) or alternative (open bars) macrophage activation after 4 h of L. chagasi infection. Fc-γ receptors associated with phagocytosis by classically activated macrophages are indicated by bars with diagonal stripes. The CD11b and CD18 subunits of the complement receptor CR3, which is involved in leishmania phagocytosis, are indicated by bars with vertical stripes. The ratio of 18S rRNA levels is indicated by a solid bar. FceR1, Fc-ɛ receptor 1; M6PR, mannose 6-phosphate receptor; ManR, mannose receptor; FceR2, Fc-ɛ receptor 2; ScavR, scavenger receptor; FcgR3, Fc-γ receptor 3; FcgRT, Fc-γ receptor α chain transporter; FcgR2, Fc-γ receptor 2; FcgR1, Fc-γ receptor 1; TgfbR2, TGF-β receptor 2; AR, androgen receptor; Cav1, caveolin-1.

The levels of transcripts encoding some proinflammatory chemokines and other molecules were modestly decreased in infected macrophage RNA samples 4 h after infection (Fig. 2A and table at http://www.int-med.uiowa.edu/research/WilsonM/Table2.htm). The MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) mRNAs were among the mRNAs whose amounts decreased modestly, which is in contrast to classical macrophage activation, in which there is acute elevation of MIP-1α mRNA levels (25). MIP-1β shares most functions with MIP-1α, and MCP-1 has been shown to contribute to healing of cutaneous leishmaniasis (39, 57); thus, these data are also indicative of classically activated or microbicidal macrophages. Similarly, the level of mRNA encoding CCR5, the common receptor for MIP-1α and MIP-1β, was decreased 4 h after infection.

Classical activation and alternative activation have been associated with the activities of the enzymes iNOS and arginase, respectively, which compete for a common substrate, arginine (9, 14, 19). NȮ generated through the action of iNOS is essential for parasite clearance from mouse macrophages (22). Arginase converts arginine to urea and ornithine, a precursor of polyamines that promotes survival of intracellular L. major and Leishmania infantum (32). Consistent with previous observations, the level of the macrophage transcript for iNOS was changed less than twofold by leishmania infection (Fig. 2A) (45, 53). The results for the change in mRNA encoding arginase I were inconsistent in the replicate arrays. Nonetheless, the level of arginase activity was not significantly changed in BALB/c macrophages after 48 h of L. chagasi infection compared to the level in the control (uninfected) macrophages. Arginase activity was not present in uninfected macrophages and ranged from 0% ± 3.6% to 1.4% ± 4.1% in triplicate cultures of 1 × 106 BALB/c bone marrow macrophages infected with opsonized promastigotes at concentrations ranging from 3 × 105 to 3 × 108 cells/ml. Nonopsonized promastigotes also failed to induce arginase activity. In contrast, incubation of bone marrow macrophages with 20 ng of IL-4/ml led to conversion of 52.7% ± 4.6% of the l-[14C]arginine in the culture to ornithine and urea (n = 6). Thus, neither the expression of iNOS, a hallmark of classical activation, nor the activity of arginase, the hallmark of alternative activation, was up-regulated by incubation with promastigotes.

In contrast to proinflammatory mRNAs, the levels of transcripts encoding some genes associated with Th2-type immune responses were increased more than twofold. CCR3, the receptor for the eosinophil chemoattractants eotaxin and eotaxin 3, has been implicated in Th2-type immune responses (58, 71). The signal corresponding to the CCR3 transcript was 2.3-fold greater in macrophages that were infected with L. chagasi than in controls. Other transcripts whose levels increased during L. chagasi infection included stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and MIP-2, whose levels increased 6.3- and 3.2-fold, respectively. SDF-1 is chemotactic for monocytes and T cells. MIP-2 is a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils and may be relevant to the outcome of leishmaniasis since neutrophils have been associated with a Th2-type response in BALB/c mice, which prevents eradication of L. major infection (30, 65). Macrophage-derived chemokine, whose transcript level increased 4.4-fold during infection, has been implicated as an amplifier of polarized Th2-type responses (27, 37), and it is produced by alternatively activated macrophages (27). Although progressive L. chagasi and L. donovani infections are not characterized by Th2-type responses in vivo (33, 69, 70), there seems to be a trend away from the Th1-type proinflammatory response at the level of the infected macrophage.

Receptors.

Expression of several receptors seemed to be modified in response to L. chagasi invasion of macrophages. Receptors described as being associated with alternative activation or an anti-inflammatory state appeared to be preferentially up-regulated (Fig. 2B). Some receptors with broad specificity, including scavenger receptors, mannose receptors, and type II Fc-epsilon receptors (CD23), have been implicated in alternative macrophage activation (25, 27, 31). In contrast, the Fc-gamma receptors have generally been associated with phagocytosis-induced classical macrophage activation (25, 31). The androgen receptor, whose transcript level increased 2.9-fold during infection, is relevant in that testosterone induces the macrophage J774 cell line to produce IL-10 (15). It has been debated whether IL-10 induces alternative macrophage activation, but IL-10 undoubtedly acts as a general suppressor of classical macrophage activation (25, 27, 31). Furthermore, testosterone significantly reduces the IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio in T cells from SJL/L mice, supporting the hypothesis that testosterone down-modulates proinflammatory responses while favoring an anti-inflammatory Th2-type environment (5). The overall pattern suggested that there were increases in the levels of transcripts encoding some receptors implicated in alternative activation and that there were decreases in the levels of transcripts for some receptors implicated in classical activation.

The subunits of CR3 CD11b and CD18 should be mentioned since CR3 contributes to leishmania phagocytosis. The levels of these subunits were only modestly decreased after phagocytosis (6, 41, 68). The level of the signal corresponding to the neuropeptide Y receptor was increased in infected macrophages. Although the neuropeptide Y receptor has not been implicated in alternative activation per se, addition of this neuropeptide at concentrations similar to those found in vivo reduced the antileishmanial response of macrophages infected with L. major (1). Caveolin-1 has been implicated in specialized endocytosis pathways that promote survival of intracellular pathogens (16, 51, 63, 64), and the level of its transcript was increased in leishmania-infected cells.

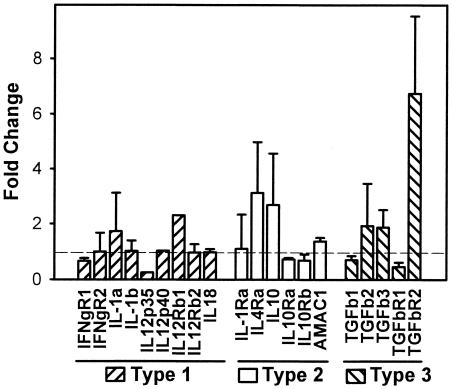

Cytokines.

Figure 3 shows the mean levels of mRNAs encoding several cytokines and cytokine receptors associated with Th1-type (type 1), Th2-type (type 2), or transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-associated (Th3-type or type 3) cell-mediated immune responses (7, 13, 21, 26, 70). According to microarray data, the levels of cytokine transcripts associated with a Th1-type immune response (TNF-α, IL-12 p40 or p35, and IL-18) were not dramatically altered by infection (Fig. 3). These findings were verified by RNase protection assays (data not shown). Replicate microarrays showed that there were increased or unchanged levels of IL-10 mRNA in different experiments (Fig. 3). Illustrating that changes did not occur exactly as predicted, the levels of mRNAs for the key signaling intermediates STAT4 and STAT6 in the IFN-γ and IL-4 pathways, respectively, changed in the direction opposite the direction that was predicted; i.e., the level of STAT4 increased (5.41 ± 0.05)-fold with infection, and the level of STAT6 remained at (0.55 ± 0.25)-fold of the control level withinfection (http://www.int-med.uiowa.edu/research/WilsonM/Table2.htm).

FIG. 3.

L. chagasi phagocytosis-induced changes in the levels of some selected transcripts associated with Th1-type, Th2-type, or Th3-type (TGF-β) cellular immune responses. The data indicate the fold changes (means ± standard deviations) in fluorescence intensity for selected transcripts in infected macrophages compared to the fluorescence intensity for noninfected macrophages. A ratio of 1.0, indicated by the horizontal line, indicates no change upon infection. The data were derived from two separate microarray experiments as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Transcripts associated with Th1-type, Th2-type, or Th3-type immune responses are indicated. IFNgR1 and IFNgR2, IFN-γ receptors 1 and 2, respectively; TGFb1, TGFb2, and TGFb3, TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3, respectively; TGFbR1 and TGFbR2, TGF-β receptors 1 and 2, respectively.

TGF-βs play a role in the progression of visceral leishmaniasis in mouse models by inhibiting Th1-type responses (3, 4, 23, 26, 70). The levels of transcripts for TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 were not changed during L. chagasi infection of macrophages, as expected since regulation of TGF-β is largely posttranslational. Nonetheless, the transcript encoding the TGF-β receptor 2 subunit, which contains the binding site for the active TGF-β dimer, was up-regulated 6.7-fold by infection. This raises the possibility that responses to TGF-β could be augmented in infected macrophages compared to the responses of their uninfected counterparts.

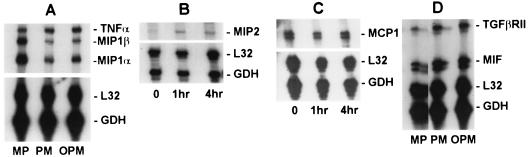

Verification of some changes in transcript abundance.

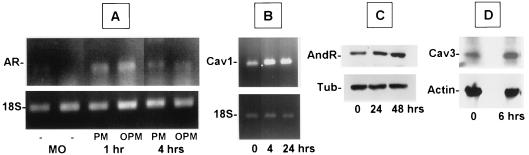

Due to the low sensitivity of microarrays, we used other methods to replicate some of the observations described above. Changes in the levels of some transcripts were verified by either RNase protection assays (Fig. 4) or RT-PCR (Fig. 5). RNase protection assays verified the increased expression of mRNAs encoding TGF-βRII and MIP-2 and decreases in MCP-1, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β expression. RNase protection assays also confirmed that there were no changes in transcripts encoding TNF-α. The increases in the levels of mRNAs for the androgen receptor and caveolin-1 were verified by RT-PCR. Increases in androgen receptor expression and caveolin-3 expression were further verified by immunoblotting (Fig. 5). Other transcripts whose levels were verified by RNase protection assays were those of RANTES and IFN-γ, and the levels were not consistently changed (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

RNase protection assays. The levels of some selected mRNAs were quantified by using RNase protection assays to verify trends observed in microarray data. Transcript levels were compared in mRNA samples from BALB/c bone marrow macrophages that were not infected (MP), were infected for 4 h with untreated promastigotes (PM), or were infected for 4 h with promastigotes that were preopsonized with C5-deficient A/J mouse serum (OPM). Parallel MP and OPM samples were used for the microarrays. Three to five micrograms of total RNA was hybridized to [32P]RNA probes representing the transcripts indicated. Each RNA sample was also hybridized to L32 and GAPDH (GDH) to control for equal loading of lanes.

FIG. 5.

RT-PCR and immunoblotting were used to determine the levels of some gene products found to change in microarrays. (A and B) RT-PCR. cDNA was generated, and sequences were amplified by using primers described in the text. Preliminary studies were performed to optimize the amount of RNA and the cycle number so that bands fell on the linear portion of the amplification curve. 18S rRNA controls were amplified by using the same amount of starting RNA for all pairs; fewer cycles than were used the test mRNA were used. RT-PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. In all cases, the amplified band corresponded to the band size predicted from the gene sequence. AR, androgen receptor; Cav1, caveolin-1; MO, uninfected macrophages; PM, macrophages infected with untreated promastigotes; OPM, macrophages infected with promastigotes that were preopsonized with C5-deficient A/J mouse serum. (C and D) The levels of androgen receptor (AndR) and caveolin-3 (Cav3) were verified on immunoblots. Total proteins from 106 uninfected bone marrow macrophages or bone marrow macrophages infected with L. chagasi for different times were analyzed to determine the levels of androgen receptor, caveolin-3, actin, or β-tubulin (Tub) by using specific antiserum or antibody as described in the text. The autoradiograms are autoradiograms of blots developed with enhanced chemiluminescence.

Overall, the data described above imply that L. chagasi infection may decrease or not change the levels of some transcripts associated with classical macrophage activation and Th1-type cytokine responses. In contrast, the levels of some transcripts that are associated with Th2-type or Th3-type cytokine responses or alternative macrophage activation may be increased.

DISCUSSION

The presence of an intracellular Leishmania sp. profoundly influences the expression of genes in an infected macrophage. Because of the inability to mount a microbicidal response to IFN-γ, this effect has been called deactivation (38, 46, 52, 55). It has become evident that macrophages can be activated in several ways, resulting in reprogramming of the pattern of gene expression towards either up- or down-modulation of microbicidal responses (2, 27). We reasoned that the type of macrophage activation initiated upon phagocytosis may determine which genes are activated or down-regulated later in infection. In the present study we examined the hypothesis that Leishmania sp. promastigotes initiate a pattern of macrophage activation that eventually leads to suppression of microbicidal responses. We used a microarray approach to study genes activated or suppressed immediately after phagocytosis of L. chagasi by bone marrow macrophages from a susceptible (BALB/c) host. Presumably, BALB/c macrophages might be susceptible to either deactivation or alternate programs of activation.

Our results suggested that phagocytosis of L. chagasi promastigotes did not immediately induce a state of generalized gene deactivation. Infection modulated the steady-state levels of many transcripts, and the greatest number of changes was observed after 4 h of infection. At this time, the percentage of transcripts that were up-regulated (12.7%) was greater than the percentage of transcripts that were down-modulated (9.38%) by L. chagasi infection. There was a general trend for genes encoding Th1-type responses or classical macrophage activation to be predominantly down-modulated, whereas many genes implicated in anti-inflammatory or Th2-type immune responses tended to be up-regulated.

The deactivation or suppressed responses to IFN-γ in macrophages infected with Leishmania spp. result in part from activation of the phosphatase SHP-1 by leishmania products (44-46). As determined in the present study, leishmania phagocytosis also influences expression of a number of genes associated with general programming of the macrophage away from a microbicidal response. Whether this reprogramming is entirely due to SHP-1 or whether other factors are also modified remains to be determined.

Macrophages can become activated through different signals to express several different phenotypes (2, 27). Classical activation induced by LPS plus IFN-γ leads to induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and MIP-1α. Classically activated murine macrophages undergo a respiratory burst and express iNOS, the enzyme that catalyzes the formation of NȮ (25, 27, 31, 40). Alternative activation has been observed in macrophages exposed to IL-4, IL-13, TGF-β, and glucocorticoids (25, 27, 31, 40). Alternatively, activated macrophages metabolize arginine through arginase rather than iNOS, they are poor at antigen presentation, and they produce AMAC, IL-1Ra, and IL-10 (2, 25, 27). The induction of arginase, a competitor for the iNOS substrate arginine, is characteristic of alternative activation. The physiological consequences of alternative activation are evident in murine macrophages infected with L. major or L. infantum, in which an inhibitor of arginase decreases parasite growth and an inhibitor of iNOS promotes parasite growth (32).

Anderson and Mosser recently reported yet another novel phenotype of macrophage activation, which they called a type II activation pattern and which is induced by ligation of Fc-γ receptors in combination with one of the Toll-like receptors, CD40, or CD44 (2, 40). Type II activation leads to expression of a mixed group of activating and deactivating cytokines, including IL-1, IL-10, TNF-α, and IL-6. In contrast, arginases are not induced and the level of IL-12 is diminished. Type II activated macrophages can induce T cells to express IL-4, suggesting that they determine the adaptive immune response to antigen. The three distinct macrophage activation phenotypes may result from different biological properties of the inducing agents (2).

Our results agree with the observation that BALB/c macrophages infected with L. chagasi are not classically activated, since the levels of transcripts encoding cytokines or chemokines implicated in classical, proinflammatory responses either did not change or decreased initially. Expression of several phagocytosis receptors implicated in classical, proinflammatory activation, including Fc-γRI and Fc-γRIIb, was also down-modulated. On the other hand, several transcripts implicated in anti-inflammatory responses or Th2-type responses (CCR3, SDF-1, macrophage-derived chemokine, MIP-2) were up-regulated. Furthermore, expression of several phagocytosis receptors implicated in alternative activation (scavenger receptor I, mannose receptor, mannose 6-phosphate receptor, Fc-ɛRI gamma chain, and Fc-ɛRII alpha chain) also increased. Arguing against a true alternative activation phenotype, however, is the fact that there was not a consistent increase in the levels of cytokines characteristic of this state (AMAC, IL-1Ra), and arginase activity was not induced in infected cells. Expression of some markers of type II activation was apparently increased in microarrays (IL-6), whereas expression of other markers was not (TNF-α) or was equivocal (IL-10) (40). Other potentially important changes included an increase in TGF-βRII expression, which could augment responses to this inhibitory cytokine and suppress the development of Th1-type responses (28, 29). Also increased was the level of the androgen receptor, which has been found to augment IL-10, antagonize NF-κB RelA, and suppress the Th1-type IFN-γ responses (5, 15). Overall, these data indicate that there is induction of a novel hybrid phenotype which is more characteristic of type II or alternative activation than of classical activation but does not strictly fit either of the definitions.

In two previously described studies the workers analyzed changes in mRNA abundance in macrophages infected with Leishmania spp. Matlashewski and Buates studied the expression of 588 genes in BALB/c macrophages infected for 96 h with L. donovani amastigotes by using a mouse cDNA expression array. The data obtained differ from our data in that the data of Matlashewski and Buates are data for macrophage gene expression at a late time point when amastigote infection is established rather than data for the response to the initial invasion of the promastigote. These authors found that 37% (90 of 245) of the gene products analyzed were down-modulated by approximately twofold, whereas only eight transcripts were up-regulated. These data support the notion of macrophage deactivation at least with reference to the selected genes at this late time in macrophage infection. In the second study Chaussabel et al. documented expression of 12,000 genes in human dendritic cells and macrophages after 16 h of infection with Toxoplasma gondii, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, L. major, L. donovani, or Brugia malayi. Although the Leishmania species and the macrophage host used in the study of Chaussabel et al. were different from the Leishmania species and host used in our study, the 16-h time point and the use of infectious promastigotes for infections make the study of Chaussabel et al. conceptually more similar to our study than the study of Matlashewski and Buates was. Not surprisingly, macrophages responded differently to each pathogen, and there were differences between macrophage and dendritic cell responses. The degrees of proinflammatory responses can be placed approximately in the following order: T. gondii > M. tuberculosis > L. major > L. donovani > B. malayi, with the latter pathogen inducing almost no response. Similar numbers of genes were up-regulated and were down-regulated in both cell types by both Leishmania species, in agreement with our data, suggesting that phagocytosis of leishmania promastigotes by macrophages does not induce an overall state of dormancy initially after phagocytosis.

Several microarray studies have documented the responses of monocytes or macrophages to microbial infection or to bacterial products. In a majority of these studies the workers used cell lines rather than primary cells. Table 4 shows the monocyte and macrophage responses to microbes or microbial products determined in some of these studies; the responses are listed as either human or murine macrophage responses.

TABLE 4.

Data from previously published studies: changes in the steady-state levels of macrophage or monocyte mRNAs encoding some macrophage inflammatory molecules after exposure to microbes or microbial productsa

| Macro- phages | Stimulus | Refer- ence(s) | Regulation

|

Others up- regulatedf | Others down- regulated | Others with no changes | Cellsf | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFκB pathb | TNF familyc | TNF-α | MIP- 1α/β | RANTES | MIP-2 | IL-1β | iNOS | IL-6 | IL-10 | IL8 | IL-12 p40 | |||||||

| Human | E. coli | 8, 48 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | PBMCs, human MN | ||||||

| Bordetella pertussis | 8 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | PBMCs | ||||||

| Listeria monocytogenes | 11 | (IκB, NF-κB) | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | COX2, MnSOD | THP-1 | ||||||

| S. aureus | 8, 48, 66 | Up | Up | Upd | Upd | Upd | Upd | Upd | Up | Up | Androgen receptor | PBMCs, human MN | ||||||

| M. tuberculosis | 10, 48 | NC | NC | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Down | Human MN | |||||||

| T. gondii | 10 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Up | Human MN | ||||||||

| L. major | 10 | NC | NC | Up | NC | NC | NC | NC | Up | Human MN | ||||||||

| L. donovani | 10 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Up | Human MN | ||||||||

| B. malayi | 10 | Down | Down | Down | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Human MN | ||||||||

| LPS | 48, 66 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | MCP-1 | Androgen receptor† | PBMCs, human MN | ||||||

| Peptidoglycan | 66 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Androgen receptor | PBMC MN | |||||||||

| IFN-γ | 66 | Up | PBMC MN | |||||||||||||||

| Murine | Salmonella | 59, 60 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | NC | Androgen receptor | Dystroglycan, cyclin D1 | RAW267.4 | |||||

| Legionella pneumophila | 43 | Up | Up | MH-S (alveolar Mφ) | ||||||||||||||

| Yersinia enterocolitica | 62 | Up | Up | Up | Up | Up | PU5-1.8 | |||||||||||

| Brucella abortus | 18 | Up (NF-κB) | Up | Up | Up | SCY proteins | RAW267.4 | |||||||||||

| M. tuberculosis | 17 | Up | Up | Up | NC | Down | NC | CXCR4 | C57BL/6 BMM | |||||||||

| L. donovani | 38 | Down | Up | Up | Down | IL-4Rα, IL-6Rα, dystroglycan | BALB/c BMM | |||||||||||

| LPS | 24, 54, 60 | Up | Up | Up | Up | NC | Up | Up | Down | Up | Up | Fc-γ1, M6PR, COX2 | Dystroglycan | RAW267.4 | ||||

| CpG | 24 | Up | Up | Up | Up | NC | NC | Up | Fc-γR2b, COX2 | Fcgr1, M6PR | RAW267.4 | |||||||

| IFN-γ | 17 | NC | Up | NC | Up | CXCR4 | C57BL/6 BMM | |||||||||||

| IL-10 | 36 | Downe | Downe | Downe | Up | Downe | Downe | Up; downe | Downe | Up | Downe | IL-4Rα, PAI2 | Caveolin-1 IRF1 | Peritoneal Mφ, BMM | ||||

| IL-4 | 67 | Arginase | RAW267.4 | |||||||||||||||

mRNAs are that are either up-regulated; down-regulated; or unchanged (NC) by the stimulus are indicated. The TNF family and the NF-κB path are indicated as being up-regulated if there is documentation that an mRNA for one or more genes in the pathway is up-regulated by the microbial stimulus. A blank indicates that the mRNA was not mentioned in the report(s).

The NF-κB path includes NF-κ1, NF-κB2, REL, RELA, RELB, and NF-κBIA.

The TNF family includes TNFSF4/OX40, TNFSF5/CD40, TNFAIP2, TNFAIP3, TRAF1, and TNFRI.

Causes a lower level of induction of IL-1α/β, IL-3, IL-6, IL-10, colony-stimulating factor, IL-8, MIP-1α/β, MIP-2α, and MIP-3α than E. coli or B. pertussis.

Effect of IL-10 on the LPS response.

PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; MN, mononuclear cells; Mφ, macrophage; BMM, bone marrow macrophages; Mn SOD, Mn superoxide dismutase; M6PR, mannose 6-phosphate receptor.

In general, macrophage exposure to gram-negative bacteria, LPS, or peptidoglycan causes up-regulation of transcripts encoding chemokines and some proinflammatory cytokines (Table 4) (48). The chemokines up-regulated by gram-negative bacteria include MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, MIP-2, and IL-8. The cytokines include TNF-α, IL-1α and -β, IL-6, and IL-12 p40. The gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus induces some inflammatory chemokine mRNAs in human cells but to a lesser extent than gram-negative bacteria do this (48). The response to M. tuberculosis is somewhat different; there is no change in NF-κB and IL-12 p40, and there is no change in IL-1β expression in murine cells. In some cases virulence is associated with decreased expression of inflammatory molecules. For example, the Yersinia enterocolitica type II secretion proteins down-modulate several inflammatory mRNAs (62), and heat-killed M. tuberculosis induces TNF-α, whereas virulent organisms do not (17).

In contrast to what happens with bacterial pathogens, the microarray experiment described above suggested that parasitic pathogens, including leishmaniae, T. gondii, and B. malayi, may enter macrophages without eliciting expression of proinflammatory response genes (10). The microarray data presented in the present study support the hypothesis that L. chagasi-infected macrophages are not deactivated but rather are activated to preferentially express genes encoding noninflammatory or anti-inflammatory molecules rather than proinflammatory markers. Some markers of alternative activation and some markers compatible with the recently described type II activation (2) were induced. We speculate that Leishmania sp. infection may lead to an atypical macrophage activation pattern after initial entry into a host macrophage, which optimizes its chances of survival in the otherwise hostile host cell environment. We suggest that there may be gradations of macrophage activation, induced according to specific characteristics of the particle or pathogen interacting with the phagocyte, that lead to a spectrum of macrophage programs and different outcomes of infection.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kevin Knudtson and Lora Huang of the Carver College of Medicine DNA core facility at the University of Iowa for Affymetrix DNA microarrays.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI45540, R01-AI48822, and R01 AI32135, by a merit review grant from the Department of Veteran's Affairs, and by NIH training grant T32 AI07511.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, A. A., A. H. Wahbi, and K. Nordlind. 2001. Neuropeptides modulate a murine monocyte/macrophage cell line capacity for phagocytosis and killing Leishmania major parasites. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 23:397-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, C. F., and D. M. Mosser. 2002. A novel phenotype for an activated macrophage: the type 2 activated macrophage. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72:101-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barral, A., M. Barral-Netto, E. C. Yong, C. E. Brownell, D. R. Twardzik, and S. G. Reed. 1993. Transforming growth factor β as a virulence mechanism for Leishmania braziliensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90:3442-3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barral-Netto, M., A. Barral, C. E. Brownell, Y. A. W. Skeiky, L. R. Ellingsworth, D. R. Twardzik, and S. G. Reed. 1992. Transforming growth factor-β in leishmanial infection: a parasite escape mechanism. Science 257:545-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bebo, B. F., J. C. Schuster, A. A. Vandenbark, and H. Offner. 1999. Androgens alter the cytokine profile and reduce encephalitogenicity of myelin-reactive T cells. J. Immunol. 162:35-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackwell, J. M. 1985. Role of macrophage complement and lectin-like receptors in binding Leishmania parasites to host macrophages. Immunol. Lett. 11:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogdan, C., A. Gessner, W. Solbach, and M. Rollinghoff. 1996. Invasion, control and persistence of Leishmania parasites. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8:517-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldrick, J. C., A. A. Alizadeh, M. Diehn, S. Dudoit, C. L. Liu, C. E. Belcher, D. Botstein, L. M. Staudt, L. O. Brown, and D. A. Relman. 2002. Stereotyped and specific gene expression programs in human innate immune responses to bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99:972-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boutard, V., R. Havouis, B. Fouqueray, C. Philippe, J.-P. Moulinoux, and L. Baud. 1995. Transforming growth factor-β stimulates arginase activity in macrophages. J. Immunol. 155:2077-2084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaussabel, D., R. T. Semnani, M. A. McDowell, D. Sacks, A. Sher, and T. B. Nutman. 2003. Unique gene expression profiles of human macrophages and dendritic cells to phylogenetically distinct parasites. Blood 102:672-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen, P., M. Bouaboula, M. Bellis, V. Baron, O. Jbilo, C. Poinot-Chazel, S. Galiegue, E. H. Hadibi, and P. Casselas. 2000. Monitoring cellular responses to Listeria monocytogenes with oligonucleotide arrays. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11181-11190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coligan, J. E., A. M. Kruisbeek, D. H. Margulies, E. M. Shevach, and W. Strober. 1991. Current protocols in immunology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 13.Constantinescu, C. S., B. D. Hondowicz, M. M. Elloso, M. Wysocka, G. Trinchieri, and P. Scott. 1998. The role of IL-12 in the maintenance of an established Th1 immune response in experimental leishmaniasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:2227-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corraliza, I. M., G. Soler, K. Eichmann, and M. Modolell. 1995. Arginase induction by suppressors of nitric oxide synthesis (IL-4, IL-10 and PGE2) in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 206:667-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Agostino, P., S. Milano, C. Barbera, G. Di Bella, M. La Rosa, V. Ferlazzo, R. Farruggio, D. M. Miceli, M. Miele, L. Castagnetta, and E. Cillari. 1999. Sex hormones modulate inflammatory mediators produced by macrophages. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 876:426-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan, M. J., J.-S. Shin, and S. N. Abraham. 2002. Microbial entry through caveolae: variations on a theme. Cell. Microbiol. 4:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrt, S., D. Schnappinger, S. Bekiranov, J. Drenkow, S. Shi, T. R. Gingeras, T. Gassterland, G. Schoolnik, and C. Nathan. 2001. Reprogramming of the macrophage transcriptome in response to interferon-γ and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: signaling roles of nitric oxide synthase-2 and phagocyte oxidase. J. Exp. Med. 194:1123-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eskra, L., A. Mathison, and G. Splitter. 2003. Microarray analysis of mRNA levels from RAW264.7 macrophages infected with Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 71:1125-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fedyk, E. R., D. Jones, H. O. D. Critchley, R. P. Phipps, T. M. Blieden, and T. A. Sprinter. 2001. Expression of stromal-derived factor-1 is decreased by IL-1 and TNF and in dermal wound healing. J. Immunol. 166:5749-5755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forget, G., K. A. Siminovitch, S. Brochu, S. Rivest, D. Radzioch, and M. Olivier. 2001. Role of host phosphotyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in the development of murine leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 31:3185-3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukaura, H., S. C. Kent, M. J. Pietrusewicz, S. J. Khoury, H. L. Weiner, and D. A. Hafler. 1996. Induction of circulating myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein-specific transforming growth factor-β1-secreting Th3 T cells by oral administration of myelin in multiple sclerosis patients. J. Clin. Investig. 98:70-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gantt, K. R., T. L. Goldman, M. A. Miller, M. L. McCormick, S. M. B. Jeronimo, E. T. Nascimento, B. E. Britigan, and M. E. Wilson. 2001. Oxidative responses of human and murine macrophages during phagocytosis of Leishmania chagasi. J. Immunol. 167:893-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gantt, K. R., S. Schultz-Cherry, N. Rodriguez, S. M. B. Jeronimo, E. T. Nascimento, T. L. Goldman, T. J. Recker, M. A. Miller, and M. E. Wilson. 2003. Activation of TGF-β by Leishmania chagasi: importance for parasite survival in macrophages. J. Immunol. 170:2613-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao, J. J., V. Diesl, T. Wittmann, D. C. Morrison, J. L. Ryan, S. N. Vogel, and M. T. Follettie. 2002. Regulation of gene expression in mouse macrophages stimulated with bacterial CpG-DNA and lipopolysaccharide. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72:1234-1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goerdt, S., and C. E. Orfanos. 1999. Other functions, other genes: alternative activation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity 10:137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomes, N. A., C. R. Gattass, V. Barreto-de-Souza, M. E. Wilson, and G. A. DosReis. 2000. Transforming growth factor beta regulates CTLA-4 suppression of cellular immunity in murine Kala-Azar. J. Immunol. 164:2001-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon, S. 2003. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:23-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorelik, L., P. E. Fields, and R. A. Flavell. 2000. TGF-β inhibits Th type 2 development through inhibition of GATA-3 expression. J. Immunol. 165:4773-4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorham, J. D., M. L. Guler, D. Fenoglio, U. Gubler, and K. M. Murphy. 1998. Low dose TGF-β attenuates IL-12 responsiveness in murine Th cells. J. Immunol. 161:1664-1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gougerot-Pocidalo, M. A., J. el Benna, C. Elbim, S. Chollet-Martin, and M. C. Dang. 2002. Regulation of human neutrophil oxidative burst by pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. J. Soc. Biol. 196:37-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gratchev, A., K. Schledzewski, P. Guillot, and S. Goerdt. 2001. Alternatively activated antigen-presenting cells: molecular repertoire, immune regulation, and healing. Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol. 15:272-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iniesta, V., L. C. Gomez-Nieto, and I. Corraliza. 2001. The inhibition of arginase by N-hydroxy-l-arginine controls the growth of Leishmania inside macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 193:777-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaye, P. M., A. J. Curry, and J. M. Blackwell. 1991. Differential production of Th1- and Th2-derived cytokines does not determine the genetically controlled or vaccine-induced rate of cure in murine visceral leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 146:2763-2770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwan, W. C., W. R. McMaster, N. Wong, and N. E. Reiner. 1992. Inhibition of expression of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules in macrophages infected with Leishmania donovani occurs at the level of gene transcription via a cyclic AMP-independent mechanism. Infect. Immun. 60:2115-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lang, R., D. Patel, J. J. Morris, R. L. Rutschman, and P. J. Murray. 2002. Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J. Immunol. 169:2253-2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mantovani, A., P. A. Gray, J. Van Damme, and S. Sozzani. 2000. Macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC). J. Leukoc. Biol. 68:400-404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matlashewski, G., and S. Buates. 2001. General suppression of macrophage gene expression during Leishmania donovani infection. J. Immunol. 166:3416-3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moll, H. 1997. The role of chemokines and accessory cells in the immunoregulation of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Behring Inst. Mitt. 99:73-78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosser, D. M. 2003. The many faces of macrophage activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73:209-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosser, D. M., and P. J. Edelson. 1985. The mouse macrophage receptor for C3bi (CR3) is a major mechanism in the phagocytosis of Leishmania promastigotes. J. Immunol. 135:2785-2789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray, H. W., G. L. Spitalny, and C. F. Nathan. 1985. Activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages in vitro and in vivo by interferon-γ. J. Immunol. 134:1619-1622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakachi, N., K. Matsunaga, T. W. Kleih, H. Friedman, and Y. Yamamoto. 2000. Differential effects of virulent versus avirulent Legionella pneumophila on chemokine gene expression in murine alveolar macropahges determined by cDNA expression array technique. Infect. Immun. 68:6069-6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nandan, D., and N. E. Reiner. 1995. Attenuation of gamma interferon-induced tyrosine phosphorylation in mononuclear phagocytes infected with Leishmania donovani: selective inhibition of signaling through Janus kinases and Stat1. Infect. Immun. 63:4495-4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nandan, D., and N. E. Reiner. 1999. Activation of phosphotyrosine phosphatase activity attenuates mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and inhibits c-FOS and nitric oxide synthase expression in macrophages infected with Leishmania donovani. Infect. Immun. 67:4055-4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nandan, D., T. Yi, M. Lopez, C. Lai, and N. E. Reiner. 2002. Leishmania EF-1α activates the Src homology 2 domain containing tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 leading to macrophage deactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:50190-50197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nathan, C. F., H. W. Murray, M. E. Wiebe, and B. Y. Rubin. 1983. Identification of interferon-γ as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and antimicrobial activity. J. Exp. Med. 158:670-689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nau, G. J., J. F. L. Richmond, A. Schlesinger, E. G. Jennings, E. S. Lander, and R. A. Young. 2002. Human macrophage activation programs induced by bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99:1503-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olivier, M., R. W. Brownsey, and N. E. Reiner. 1992. Defective stimulus-response coupling in human monocytes infected with Leishmania donovani is associated with altered activation and translocation of protein kinase C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89:7481-7485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearson, R. D., and A. D. Q. Sousa. 1996. Clinical spectrum of leishmaniasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pelkmans, L., J. Kartenbeck, and A. Helenius. 2001. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 reveals a new two-step vesicular-transport pathway to the ER. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:473-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prive, C., and A. Descoteaux. 2000. Leishmania donovani promastigotes evade the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 during infection of naive macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:2235-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Proudfoot, L., A. V. Nikolaev, G.-J. Feng, X.-Q. Wei, M. A. Ferguson, J. S. Brimacombe, and F. Y. Liew. 1996. Regulation of the expression of nitric oxide synthase and leishmanicidal activity by glycoconjugates of Leishmania lipophosphoglycan in murine macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93:10984-10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ravasi, T., C. Wells, A. Forrest, D. M. Underhill, B. J. Wainwright, A. Aderem, S. Grimmond, and D. A. Hume. 2002. Generation of diversity in the innate immune system: macrophage heterogeneity arises from gene-autonomous transcriptional probability of individual inducible genes. J. Immunol. 168:44-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ray, M., A. A. Gam, and R. A. Boykins. 2000. Inhibition of interferon-γ signaling by Leishmania donovani. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1121-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reiner, N. E. 1994. Altered cell signaling and mononuclear phagocyte deactivation during intracellular infection. Immunol. Today 15:374-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritter, U., and H. Korner. 2002. Divergent expression of inflammatory dermal chemokines in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 24:295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romagnani, S. 2002. Cytokines and chemoattractants in allergic inflammation. Mol. Immunol. 38:881-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenberger, C. M., A. J. Pollard, and B. B. Finlay. 2001. Gene array technology to determine host responses to Salmonella. Microbes Infect. 3:1353-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosenberger, C. M., M. G. Scott, M. R. Gold, R. E. W. Hancock, and B. B. Finlay. 2000. Salmonella typhimurium infection and lipopolysaccharide stimulation induce similar changes in macrophage gene expression. J. Immunol. 164:5894-5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rueesll, A. S., and U. T. Ruegg. 1980. Arginase production by peritoneal macrophages: a new assay. J. Immunol. Methods 32:375-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sauvonet, N., B. Pradet-Balade, J. A. Garcia-Sanz, and G. R. Cornelis. 2002. Regulation of mRNA expression in macrophages after Yersinia enterocolitica infection. J. Biol. Chem. 277:25133-25142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shin, J.-S., and S. N. Abraham. 2001. Co-option of endocytic functions of cellular caveolae by pathogens. Immunology 102:2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shin, J.-S., Z. Gao, and S. N. Abraham. 2000. Involvement of cellular caveolae in bacterial entry into mast cells. Science 289:785-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tacchini-Cottier, F., C. Zweifel, Y. Belkaid, C. Mukankundiye, M. Vasei, P. Launois, G. Milon, and J. A. Louis. 2000. An immunomodulatory function for neutrophils during the induction of a CD4+ Th2 response in BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania major. J. Immunol. 165:2628-2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang, Z.-M., C. Liu, and R. Dziarski. 2000. Chemokines are the main proinflammatory mediators in human monocytes activated by Staphylococcus aureus, peptidoglycan, and endotoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20260-20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Welch, J. S., L. Escoubet-Lozach, D. B. Sykes, K. Liddiard, D. R. Greaves, and C. K. Glass. 2002. TH2 cytokines and allergic challenge induce Ym1 expression in macrophages by a STAT6-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 277:42821-42829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson, M. E., and R. D. Pearson. 1986. Evidence that Leishmania donovani utilizes a mannose receptor on human mononuclear phagocytes to establish intracellular parasitism. J. Immunol. 136:4681-4688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson, M. E., M. Sandor, A. M. Blum, B. M. Young, A. Metwali, D. Elliott, R. G. Lynch, and J. V. Weinstock. 1996. Local suppression of IFN-γ in hepatic granulomas correlates with tissue-specific replication of Leishmania chagasi. J. Immunol. 156:2231-2239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilson, M. E., B. M. Young, B. L. Davidson, K. A. Mente, and S. E. McGowan. 1998. The importance of transforming growth factor-β in murine visceral leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 161:6148-6155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xanthou, G., C. E. Duchesnes, T. J. Williams, and J. E. Pease. 2003. CCR3 functional responses are regulated by both CXCR3 and its ligands CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXC11. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:2241-2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]