Abstract

Background

Mutans streptococci are a group of bacteria significantly contributing to tooth decay. Their genetic variability is however still not well understood.

Results

Genomes of 6 clinical S. mutans isolates of different origins, one isolate of S. sobrinus (DSM 20742) and one isolate of S. ratti (DSM 20564) were sequenced and comparatively analyzed. Genome alignment revealed a mosaic-like structure of genome arrangement. Genes related to pathogenicity are found to have high variations among the strains, whereas genes for oxidative stress resistance are well conserved, indicating the importance of this trait in the dental biofilm community. Analysis of genome-scale metabolic networks revealed significant differences in 42 pathways. A striking dissimilarity is the unique presence of two lactate oxidases in S. sobrinus DSM 20742, probably indicating an unusual capability of this strain in producing H2O2 and expanding its ecological niche. In addition, lactate oxidases may form with other enzymes a novel energetic pathway in S. sobrinus DSM 20742 that can remedy its deficiency in citrate utilization pathway.

Using 67 S. mutans genomes currently available including the strains sequenced in this study, we estimates the theoretical core genome size of S. mutans, and performed modeling of S. mutans pan-genome by applying different fitting models. An “open” pan-genome was inferred.

Conclusions

The comparative genome analyses revealed diversities in the mutans streptococci group, especially with respect to the virulence related genes and metabolic pathways. The results are helpful for better understanding the evolution and adaptive mechanisms of these oral pathogen microorganisms and for combating them.

Keywords: Mutans Streptococci, Streptococcus Mutans, Streptococcus Ratti, Streptococcus Sobrinus, Comparative Genomics, Core-genome, Pan-genome, Pathogenicity, Lactate Oxidase, Metabolic Network

Background

Traditionally and supported by 16S rRNA gene and rnpB gene sequence analyses, the genus Streptococcus is divided into several groups, with the mutans group streptococci consisting of the species S. mutans, S. sobrinus, S. ratti, S. criceti, S. downei, S. macacae, and – but controversially discussed – S. ferus (for update refer to http://www.bacterio.net/s/streptococcus.html) [1]. Mutans streptococci are considered significant contributors to the development of dental caries [2]. By attaching to the tooth surfaces and forming biofilms, they can tolerate and adapt to the harsh and rapidly changing physiological conditions of the oral cavity such as extreme acidity, fluctuation of nutrients, reactive oxygen species, and other environmental stresses [3]. They occasionally also cause bacteremia, abscesses, and infective endocarditis [4,5]. Many strains of mutans streptococci are genetically competent, i.e. they can take up DNA fragments from the environment and recombine them into their chromosome, an important mechanism for horizontal gene transfer (HGT). The ability of some bacteria to generate diversity through HGT provides a selective advantage to these microbes in their adaptation to host eco-niches and evasion of immune responses [6,7]. Due to diversities in the genetic contents between different isolates, the genome content of a single isolate does not necessarily represent the genomic potential of a certain species. With the rapid development of DNA sequencing technologies, the steadily increasing genome data enable us to dig the evolutionary and genetic information of a species from a pan-genome perspective. In 2002, the release of the genome sequence of S. mutans UA159, the first genome sequence of mutans group streptococci, has greatly helped in understanding the robustness and complexity of S. mutans as an oral and odontogenic (e.g. infective endocarditis and abscesses) pathogen [8]. Later, after the genome sequence of S. mutans NN2025 became available, a comparative genomic analysis of S. mutans NN2025 and UA159 provides insights into chromosomal shuffling and species-specific contents [9]. Recently, Cornejo et al. have studied the evolutionary and population genomics of S. mutans based on 57 S. mutans draft genomes and revealed a high lateral gene transfer (LGT) rate of S. mutans[10].

In this study, we determined the whole genome sequences of six S. mutans strains (5DC8, KK21, KK23, AC4446, ATCC 25175 and NCTC 11060), one S. ratti strain (DSM 20564) and one S. sobrinus strain (DSM 20742) and performed cross-comparison with the genome contents of S. mutans UA159 and NN2025, focusing on issues that are highly related to pathogenicity. The core- and pan-genome of S. mutans was analyzed by including 67 currently available S. mutans genome sequences. By constructing and comparing the genome-scale metabolic networks, the diversities in sub-networks (pathways) are systematically revealed. The results should be helpful for understanding the evolution and pathogenicity, as well as for prevention and treatment, of these very common opportunistic pathogens.

Results and discussion

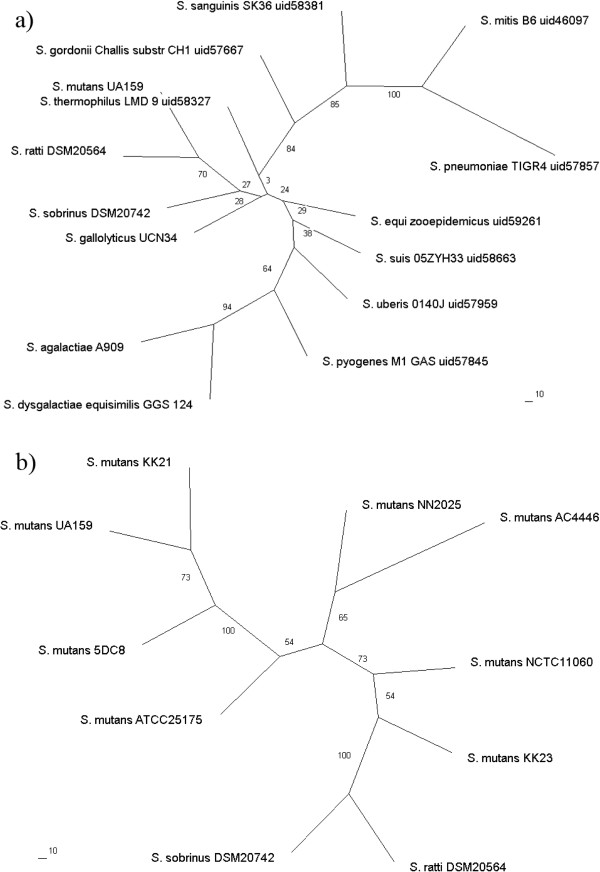

Genome sequencing, assembly and annotation of eight mutans streptococci strains

As expected, the overall genomic features of the eight S. mutans strains are more close to each other than to S. ratti and S. sobrinus. This is consistent with the results of the phylogenetic analysis, as visualized by the phylogenetic tree constructed based on 16S rRNA and core genes single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) information shown in Figure 1. An overview of the genome assemblies and annotations of the 6 S. mutans isolates as well as S. ratti DSM 20564 and S. sobrinus DSM 20742 is summarized in Table 1 in comparison with two previously sequenced S. mutans strains, namely UA159 and S. mutans NN2025. The average GC contents are in the range of low GC organisms [8]. The genome sizes are very close to each other, with the largest one from S. sobrinus DSM 20742 and the smallest one from S. mutans KK23 showing merely 5.7% differences. The total numbers of protein-coding sequences per genome are also similar among all the strains compared.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the 10 mutans streptococci strains compared in this study and their phylogenetic relationship to other Streptococcus species with genomes known before 01/01/2011. a) 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree of Streptococcus species with genomes known before 01/01/2011 (Since the 16S rRNA sequences were almost identical between the different S. mutans strains, only UA159 is shown as representative). b) Phylogenetic tree of mutans streptococci constructed with the core-genome SNPs obtained by PGAP pipeline [11]. All phylogenetic trees were constructed using ClustalX and Phylip by applying the maximum likelihood (ML) method with bootstrap value set to 100. Values beside branches depict ML bootstrap support values. The scale bars in the unit of “substitution/site” are shown below the trees.

Table 1.

Genome assembly and annotation of eight newly sequenced mutans streptococci strains in comparison with previously sequenced S. mutans strains UA159 and S. mutans NN2025

| S. mutans UA159 | S. mutans NN2025 | S. mutans 5DC8 | S. mutans KK21 | S. mutans KK23 | S. mutans AC4446 | S. mutans ATCC 25175 | S. mutans NCTC 11060 | S. ratti DSM 20564 | S. sobrinus DSM 20742 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

NC_004350.2 |

NC_013928.1 |

AOBX 00000000 |

AOBY 00000000 |

AOBZ 00000000 |

AOCA 00000000 |

AOCB 00000000 |

AOCC 00000000 |

AOCD 00000000 |

AOCE 00000000 |

|

Total Length |

2,030,921 |

2,013,587 |

2,010,935 |

2,034,586 |

1,976,057 |

2,003,537 |

1,999,532 |

2,021,202 |

2,037,184 |

2,096,203 |

|

Contigs |

Complete |

Complete |

9 |

2 |

38 |

42 |

10 |

36 |

182 |

283 |

|

N50 size |

Complete |

Complete |

354,736 |

1,622,660 |

134,323 |

167,413 |

233,425 |

94,580 |

23,860 |

12,417 |

|

N90 size |

Complete |

Complete |

325,634 |

411,935 |

38,851 |

26,425 |

107,076 |

43,987 |

6,098 |

3,659 |

|

G + C content |

36.82% |

36.85% |

36.90% |

36.81% |

36.68% |

36.90% |

36.87% |

36.98% |

40.29% |

43.46% |

|

Total Genes |

2040 |

1975 |

2,004 |

2,031 |

1,933 |

1,999 |

1,982 |

1,982 |

1,995 |

2,057 |

| Protein Coding Genes | 1,960 | 1,895 | 1,924 | 1,949 | 1,907 | 1,919 | 1,903 | 1,915 | 1,965 | 2,032 |

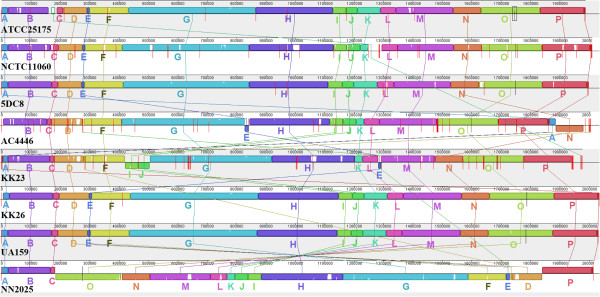

Chromosomal rearrangement of the S. mutans strains

Genome rearrangements have important effects on bacterial phenotypes and the evolution of bacterial genomes [12]. A comparison of the genomes of S. mutans NN2025 and UA159 discovered a large genomic inversion across the replication axis and similar genomic variations were also confirmed among 95 clinical S. mutans isolates using long-PCR analysis [9]. In this study, genome rearrangements among the eight S. mutans strains are determined by genome alignment using the MAUVE software [13]. The results are presented in Figure 2, which shows the locally collinear blocks (LCBs) representing the landmarks, i.e. the homologous/conserved regions shared by all the input sequences in the chromosomes. A LCB is defined as a collinear (consistent) set of exactly matched subsequences (multiple maximal unique matches, namely ‘multi-MUMs’) which are shared by all the chromosomes considered, appear once in each chromosome and are bordered on both sides by mismatched nucleotides. The weight (the sum of the lengths of the included multi-MUMs) of a LCB serves as a measure of confidence that it is a true homologous region rather than a random match.

Figure 2.

Comparison of local collinear blocks (LCBs) of chromosomal sequences of the eight S. mutans strains. In total 16 local LCBs, marked as A to P, were generated and compared by applying the MAUVE software [13,14] with default settings and using strain UA159 as reference. The red vertical bars indicate contig ends. The white areas inside each LCB show regions with low similarities.

As shown in Figure 2, 16 LCBs (marked as A to P) are identified by multi-alignment of the eight S. mutans genome sequences. Compared to UA159 and NN2025, the chromosome segment represented by LCB E is reversely inserted between the LCB G and H in the strain AC4446, and between the LCB L and M in the strain KK23. This segment is related to the genomic island “SMU.100-SMU.116” of S. mutans UA159 which mainly contains sorbitol phosphotransferase system (PTS), transposase and hypothetical proteins [15]. LCB N is found to be reversed and relocated to the position between LCB A and B in the strain AC4446. A cluster of tRNA genes is found to be located downstream of LCB N. In KK23, LCB I and J are moved to position between LCB F and G. A tRNA-Gln and a tRNA-Tyr is found to be adjacent to the left of LCB I. LCB K in NCTC 11060, AC4446, KK23 and NN2025 are very similar to each other but much smaller than those of other strains (with sequence length reduced about two-thirds). The missing sequence corresponds to the genomic island TnSmu2 of S. mutans which harbors a nonribosomal peptide synthetase-polyketide synthase gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of pigments [16]. Using the known information about genomic islands in S. mutans UA159, additional genomic islands were found to be present/absent in the mutans streptococci strains of this study [15,17] (see Additional file 1). Furthermore, there are much more diversities as shown by the white areas inside the LCBs which show regions with low similarities. However, it should be noticed that there might be more genome rearrangements among the strains, because draft genome sequences are used in current analysis and all contigs in each genome are sorted according to the reference genome sequence of the strain UA159.

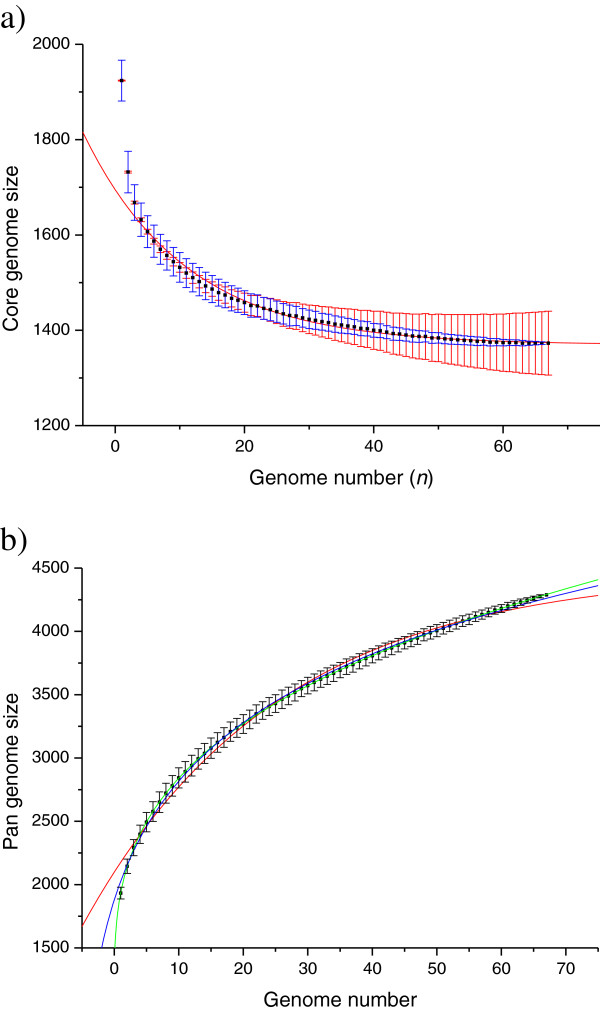

Core- and pan-genome analysis of S. mutans

The genetic variability within species in the domain Bacteria is much larger than that found in other domains of life. The gene content between pairs of isolates can diverge by as much as 30% in species like Streptococcus pneumoniae[18]. This unexpected finding led to the introduction of the pan-genome concept, which describes the sum of genes that can be found in a given bacterial species [19,20]. The genome of any isolate is thus composed of a “core-genome” shared with all strains of this particular species, and a “dispensable genome” that accounts for the phenotypic differences between strains. The pan-genome is usually much larger than the genome of any single isolate, constituting a reservoir that could enhance the ability of many bacteria to survive in stressful environments. The pan-genome concept has important consequences for the way we understand bacterial evolution, adaptation, and population structure, as well as for more applied issues such as vaccine design or the identification of virulence genes [21]. In this study, we performed core-genome and pan-genome analyses of 67 S. mutans strains, including the eight S. mutans strains sequenced in this study and 59 S. mutans strains with genome available in NCBI till April 2013.

Core-genome

The core-genome size of the 67 S. mutans strains was calculated to be 1,373. Detailed information of the core genes are provided in the Additional file 2. To estimate the theoretical core-genome size achievable with an infinite number of S. mutans genomes, core-genome size medians corresponding to different genome numbers as shown in Figure 3a by the red rectangles were first calculated by random sampling 1,000 genome combinations of n genomes out of the 67 S. mutans genomes. Then, we applied the exponential regression core-genome model proposed previously by Tettelin et al. [19,20] to fit the median data points of the core-genome sizes, where Kc, τc and Ω are parameters, n represents the number of genomes, and Ω stands for the theoretical core-genome size. To take into consideration the different deviations of the core-genome size medians, as clearly indicated by the blue error bars in Figure 3a, we modified the fitting process by introducing the genome number as weight to the corresponding data point. The fitting parameters thus obtained are as follows: r2 = 0.97403, Kc = 325.74718 ± 10.00912,Ω = 1,369.41225 ± 1.986,τc = 15.90248 ± 0.66807 (Detailed information of all core and pan-genome modeling are given in Additional file 3). Using this fitting result to describe the core-genome of S. mutans, the theoretical core-genome size (Ω) was estimated to be around 1,370 genes, which is slightly lower than the calculated core-genome size (1,373) using 67 genomes. Compared with other streptococcus species, the core-genome of S. mutans is at the same level to the core-genome of S. pyogenes (1,400 genes determined using 11 strains), less than that of S. pneumoniae (1,647 genes determined using 47 strains) and S. agalactiae (1,800 genes determined using eight strains) [19,22,23]. However, we should be cautious with such comparison. In a recent study of Cornejo et al. [10], the core genome size of S. mutans was determined as 1,490 by using 57 S. mutans genomes which is obviously different to the core genome size of S. mutans we estimated, although we included the 57 S. mutans genomes used by Cornejo et al. in our study. The difference can be caused by different reasons, such as difference in the correction step for core gene determination and, very likely, different methods and parameter settings used for determining orthologs. Apparently, we have used a more stringent process to determine orthologs which led to smaller core genome size of S. mutans estimated.

Figure 3.

Core and pan-genome model of 67 S. mutans genomes. a) Core-genome model of S. mutans. The core-genome size (number of common genes) is plotted as a function of the number (n) of genomes according to a previously proposed model where Kc, τc and Ω are model parameters. Red rectangles are the medians of the core-genome sizes calculated by random sampling 1000 different genome combinations of n genomes out of 67 genomes. Blue bars are the standard deviation of the medians. The red bars are weights used for model fitting and the red curve is the fitting result. b) Pan genome modeling of S. mutans genomes using three models, y = a + bxc, y = a − bln(x + c) and y = a × e− x/b + c (where a, b and c are parameters), represented by green, blue and red curves respectively. Black rectangles are the medians of the pan-genome sizes calculated by random sampling 1000 different genomes combination of n genomes out of 67 genomes, and black bars are the standard deviations of the medians.

Pan-genome

We applied three models, namely y = a + bxc, y = a − bln(x + c) and y = a × e− x/b + c (where a, b and c are parameters) for modeling the pan-genome of S. mutans, as shown in Figure 3b by green, blue and red curves respectively (all fitting results are detailed in Additional file 3). Both the fitting results of using y = a + bxc and y = a − bln(x + c) indicated an infinite pan-genome, while the fitting result of using y = a × e− x/b + c resulted in a negative value of the parameter a, suggesting a finite pan-genome However, the last fitting shows obvious deviations to many of the data points. Especially, the deviations even become larger with increased genome numbers, indicating that this model is not suitable. The best fitting result obtained with the model y = a + bxc shows fittings to all the data points with very high confidence. Based on this model, the pan-genome of S. mutans is still “open” while 67 genomes were included, and the expected average new gene number with the addition of a new genome is estimated to be 15. The infinite pan-genome was first proposed by Tettelin et al. for S. agalactiae based on the use of 9 S. agalactiae genomes. The three regression models used in this study are all based on the assumption that contingency genes are independently sampled from the pan-genome with equal probability, except in the case of “specific/unique genes”, which are modeled as unique events that appear only once in the entire global population. Hogg et al. [24] proposed a finite supragenome model for pan-genome based on a different supposition that contingency genes are sampled from the pan-genome with unequal probability. By applying this finite supragenome model to 44 S. pneumoniae genomes, the predicted number of new genes drops sharply to zero when the number of genomes exceeds 50. However, in the case of S. mutans we could not observe such sharp decrease of new gene number even after 67 genomes were included. In the study of Cornejo et al. [10], they proposed a finite pan-genome for S. mutans, after they used a special “pseudogene cluster” identification process to exclude about 30% of the rare genes that are considered to be pseudogenes. However, they didn’t provide detailed parameters they obtained from fitting. Our modeling using the 67 S. mutans genomes by applying the model described above without any restrictions pointed to an infinite pan-genome of S. mutans. However, we would like to understand this predicted “infinite” pan-genome as follows: 1) a “pan-genome” should be considered as “dynamic” rather than “static”, which means the pan-genome content is changing during the evolution, it does not matter if its size is infinite or finite; 2) The change of a pan-genome content can be caused by the acquirement of new genes or by the loss of genes; 3) The actual pan-genome size can be more stable than the content of the pan-genome but can also change during evolution coupled with the change of the environment. Thus, without considering the “gene loss events”, it’s quite understandable to have a “growing” or “infinite” pan-genome as gene acquirement occurs no matter how slow it might be. Interestingly, Cornejo et al. found a high rate of LGT in S. mutans, where many genes were acquired from related streptococci and bacterial strains predominantly residing not only in the oral cavity, but also in the respiratory tract, the digestive tract, cattle, genitalia, in insect pathogens and in the environment in general [10]. Such high rate of LGT might also lead to a continuously growing pan-genome.

Gene content-based comparative analysis of 10 mutans streptococci strains

The annotated protein sequences of all the genomes studied were cross-compared based on alleles/ortholog groups established by the program OrthoMCL [25]. In total, 2,211 putative alleles/ortholog groups are established, as documented in Additional file 4. A pair-wise comparison of the protein coding sequences between each two strains is shown in Table 2. It is clear to see that remarkable differences in protein coding sequences exist between the strains, even inside the same species of S. mutans. In the following sections, systems that are highly related to stress resistance and pathogenicity are presented and discussed. As all the following results are based on putative alleles/ortholog groups established by OrthoMCL, if not otherwise specified, the word “putative allele(s)/ortholog(s)” is omitted in the following text.

Table 2.

Unique protein coding sequences (CDSs) revealed by ortholog analysis between the different strains of this study

| Unique CDSs in comparision to | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

S. mutans UA159 |

S. mutans NN2025 |

S. mutans 5DC8 |

S. mutans KK21 |

S. mutans KK23 |

S. mutans AC4446 |

S. mutans ATCC 25175 |

S. mutans NCTC 11060 |

S. ratti DSM 20564 |

S. sobrinus DSM 20742 |

All others |

|

S. mutans UA159 |

|

216 |

125 |

63 |

230 |

221 |

166 |

212 |

427 |

566 |

42 |

|

S. mutans NN2025 |

150 |

|

150 |

150 |

133 |

102 |

182 |

167 |

358 |

510 |

24 |

|

S. mutans 5DC8 |

85 |

176 |

|

52 |

164 |

161 |

132 |

153 |

379 |

522 |

31 |

|

S. mutans KK21 |

47 |

200 |

76 |

|

190 |

184 |

127 |

175 |

402 |

544 |

3 |

|

S. mutans KK23 |

183 |

152 |

157 |

159 |

|

146 |

173 |

175 |

387 |

525 |

56 |

|

S. mutans AC4446 |

145 |

92 |

125 |

124 |

117 |

|

159 |

146 |

364 |

502 |

31 |

|

S. mutans ATCC 25175 |

117 |

199 |

123 |

94 |

171 |

186 |

|

146 |

373 |

525 |

33 |

|

S. mutans NCTC 11060 |

126 |

147 |

107 |

105 |

136 |

136 |

109 |

|

334 |

488 |

34 |

|

S. ratti DSM 20564 |

432 |

429 |

424 |

423 |

439 |

445 |

427 |

425 |

|

564 |

289 |

| S. sobrinus DSM 20742 | 616 | 626 | 612 | 610 | 622 | 628 | 624 | 624 | 609 | 492 | |

High diversities of the competence development regulation module

In a previous study we have systematically discussed the two-component signal transduction systems (TCSTSs) in the 10 mutans streptococci strains [26]. ComDE, one of the TCSTS is directly related to competence development. Competence development is a complex process involving sophisticated regulatory networks that trigger the capacity of bacterial cells to take up exogenous DNA from the environment. This phenomenon is frequently encountered in bacteria of the oral cavity, e.g., S. mutans[27]. In S. mutans, ComX, an alternative sigma factor, drives the transcription of the so called ‘late-competence genes’ required for genetic transformation. ComX activity is modulated by the inputs from two types of signal pathways, namely the competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) dependent competence regulation system and CSP-independent competence regulation system. ComX and the ‘late-competence genes’ regulated by ComX as labeled by boldface in Table 3, are highly conserved even between the species, indicating that all mutans streptococci studied here might have the potential ability of transforming to genetic competence state. On the other hand, the upstream signal pathways regulating the activity of ComX show high variety as discussed in details below.

Table 3.

Distribution of competence development-related systems in the 10 mutans streptococci strains

| Name | Function |

S. mutans |

S. mutans |

S. mutans |

S. mutans |

S. mutans |

S. mutans |

S. mutans |

S. mutans |

S. ratti |

S. sobrinus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UA159 | NN2025 | 5DC8 | KK21 | KK23 | AC4446 | ATCC 25175 | NCTC 11060 | DSM 20564 | DSM 20742 | ||

| ComA/ |

Competence factor & nonlantibiotic mutacin transporting ATP-binding/permease protein |

SMU.286 |

GI|290581206 |

D816_01150 |

D817_01300 |

D818_01134 |

D819_01163 |

D820_01336 |

D821_01208 |

D822_01584 |

D823_05343 |

| SMU.1881c |

GI|290579788 |

D816_08453 |

D817_08643 |

- |

D819_07724 |

|

D821_08449 |

D822_08325- |

D823_01400 |

||

| NlmT | |||||||||||

| ComB/ |

Accessory factor for NlmT |

SMU.287 |

GI|290581205 |

D816_01155 |

D817_01305 |

D818_01139 |

D819_01168 |

D820_01341 |

D821_01213 |

D822_01589 |

D823_05923 |

| NlmE | |||||||||||

| ComC |

S. mutans specific competence stimulating peptide, precursor |

SMU.1915 |

GI|290579762 |

D816_08588 |

D817_08778 |

D818_08368 |

D819_07839 |

D820_08520 |

D821_08549 |

- |

- |

| SepM |

cell surface-associated protease; Cleavage CSP. |

SMU.518 |

GI|290580977 |

D816_02205 |

D817_02448 |

D818_02735 |

D819_02254 |

D820_02420 |

D821_02274 |

D822_04126 |

D823_08607 |

| ComD |

histidine kinase |

SMU.1916 |

GI|290579761 |

D816_08593 |

D817_08783 |

D818_08373 |

D819_07844 |

D820_08525 |

D821_08554 |

|

D823_05333 |

| ComE |

response regulator |

SMU.1917 |

GI|290579760 |

D816_08598 |

D817_08788 |

D818_08378 |

D819_07849 |

D820_08530 |

D821_08559 |

|

D823_05328 |

| D823_7992 | |||||||||||

| HtrA |

serine protease |

SMU.2164 |

GI|290581420 |

D816_09733 |

D817_00015 D817_09913 |

D818_00020 |

D819_09056 |

D820_09650 |

D821_09748 |

D822_05851 |

D823_03191 |

| HdrM |

high density responsive membrane protein |

SMU.1855 |

GI|290579809 |

D816_08353 |

D817_08543 |

D818_08143 |

D819_07614 |

D820_08345 |

D821_08319 |

D822_08240 |

D823_08222 |

| HdrR |

high density responsive regulator |

SMU.1854 |

GI|290579810 |

D816_08348 |

D817_08538 |

D818_08138 |

D819_07609 |

D820_08340 |

D821_08314 |

- |

- |

| BrsM |

|

SMU.2081 |

GI|290581347 |

D816_09358 |

D817_09538 |

D818_09198 |

D819_08671 |

D820_09275 |

D821_09348 |

- |

- |

| BrsR |

|

SMU.2080 |

GI|290581346 |

D816_09353 |

D817_09533 |

D818_09193 |

D819_08666 |

D820_09270 |

D821_09343 |

D822_05085 |

- |

| OppD |

oligopeptide ABC transporter |

SMU.258 |

GI|290581226 |

D816_01025 |

D817_01175 |

D818_01039 |

D819_01063 |

D820_01211 |

D821_01051 |

D822_05611 |

D823_04322 |

| ComS |

comX-inducing peptide (XIP) precursor |

NC_004350.2 |

NC_013928.1 |

D816_00277 |

D817_00297 |

D818_00297 |

D819_00203 |

D820_00247 |

D821_00253 |

D822_01077 |

- |

| (62613 - 62666)a |

(60952- 61005)b |

||||||||||

| ComR |

ComS receptor |

SMU.61 |

GI|290579576 |

D816_00275 |

D817_00295 |

D818_00294 |

D819_00200 |

D820_00245 |

D821_00250 |

D822_01080 |

|

| ComX(SigX) |

competence-specific sigma factor |

SMU.1997 |

GI|290579687 |

D816_08973 |

D817_09163 |

D818_08748 |

D819_08219 |

D820_08900 |

D821_08929 |

D822_07328 |

D823_08887 |

|

ComEA |

competence protein |

SMU.625 |

GI|290580890 |

D816_02675 |

D817_02923 |

D818_03217 |

D819_02694 |

D820_02880 |

D821_02784 |

D822_02674 |

D823_08107 |

|

ComEC |

competence protein; possible integral membrane protein |

SMU.626 |

GI|290580889 |

D816_02680 |

D817_02928 |

D818_03222 |

D819_02699 |

D820_02885 |

D821_02789 |

D822_02679 |

D823_08117 |

|

CoiA |

competence protein CoiA |

SMU.644 |

GI|290580870 |

D816_02775 |

D817_03018 |

D818_03322 |

D819_02786 |

D820_02970 |

D821_02879 |

D822_02739 |

D823_01025 |

|

EndA |

competence associated membrane nuclease (DNA-entry nuclease) |

SMU.1523 |

GI|290580108 |

D816_06842 |

D817_07008 |

D818_06659 |

D819_06647 |

D820_06860 |

D821_06857 |

D822_03254 |

D823_09687 |

|

ComG |

competence protein G |

SMU.1981c |

GI|290579702 |

D816_08898 |

D817_09088 |

D818_08673 |

D819_08144 |

D820_08825 |

D821_08854 |

D822_07418 |

D823_01170 |

|

ComYD |

competence protein ComYD |

SMU.1983 |

GI|290579700 |

D816_08908 |

D817_09098 |

D818_08683 |

D819_08154 |

D820_08835 |

D821_08864 |

D822_07408 |

D823_01160 |

|

ComYC |

competence protein ComYC |

SMU.1984 |

GI|290579699 |

D816_08913 |

D817_09103 |

D818_08688 |

D819_08159 |

D820_08840 |

D821_08869 |

D822_07403 |

D823_01155 |

| |

possible competence-induced protein |

SMU.2075c |

GI|290581342 |

D816_09328 |

D817_09508 |

D818_09168 |

D819_08641 |

D820_09245 |

D821_09318 |

D822_05110 |

D823_03558 |

|

CinA |

competence damage-inducible protein A |

SMU.2086 |

GI|290581351 |

D816_09383 |

D817_09563 |

D818_09218 |

D819_08691 |

D820_09295 |

D821_09368 |

D822_05060 |

D823_03593 |

|

ComYB |

competence protein; general (type II) secretory pathway protein |

SMU.1985 |

GI|290579698 |

D816_08918 |

D817_09108 |

D818_08693 |

D819_08164 |

D820_08845 |

D821_08874 |

D822_07398 |

D823_01150 |

|

ComYA |

late competence protein; type II secretion system protein |

SMU.1987 |

GI|290579697 |

D816_08923 |

D817_09113 |

D818_08698 |

D819_08169 |

D820_08850 |

D821_08879 |

D822_07393 |

D823_01145 |

|

ComFC |

late competence protein required for DNA uptake |

SMU.499 |

GI|290580999 |

D816_02100 |

D817_02348 |

D818_02650 |

D819_02154 |

D820_02290 |

D821_02159 |

D822_06218 |

D823_02981 |

|

ComFA |

late competence protein F |

SMU.498 |

GI|290581000 |

D816_02095 |

D817_02343 |

D818_02645 |

D819_02149 |

D820_02285 |

D821_02154 |

D822_06223 |

D823_02986 |

| CinA | competence damage-inducible protein A; | SMU.2086 | GI|290581351 | D816_09383 | D817_09563 | D818_09218 | D819_08691 | D820_09295 | D821_09368 | D822_05060 | D823_03593 |

In the case that more than one paralogs were found, the most similar ortholog is marked in italic. The rows related to highly conserved ‘late-competence genes’ were shown in boldface. The missing of ComDE in S. ratti DSM 20564 has been published in our previous study [26].

alocation of comS in S. mutans UA159.

blocation of comS in S. mutans NN2025.

CSP-dependent competence regulation system

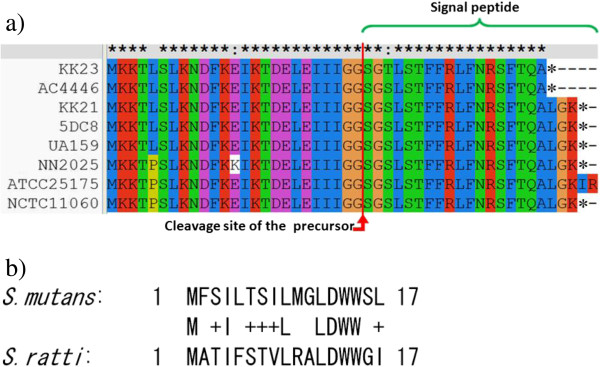

It has been reported that the ComABCDE system in S. mutans combines the action of the two ortholog systems which are present as ComABCDE and BlpABCRH in S. pneumoniae and involved in competence regulation and bacteriocins regulation, respectively. It should be noticed that, ComAB have been primarily considered to be the transporter of ComC, the precursor of CSP. Later, ComAB have been renamed as NlmTE as they were found to function together as transporter of nonlantibiotic bacteriocins, while another gene pair CslAB was supposed to be the transporter of ComC [28]. However, a recent study confirms that ComAB is indeed a transporter both for nonlantibiotic bacteriocin and the peptide pheromone CSP [29].

In S. mutans, the comC-encoded prepeptide of CSP has a leader sequence containing a conserved double glycine (GG), at which the leader sequence is cleaved during transporting by ComAB to generate the mature signal peptide (CSP-21) containing 21 amino acid residues [28,30,31]. Recent studies show that an extracellular protease, SepM (SMU.518), is involved in the further processing of CSP-21 by removing the “LGK” residues in the C-terminal to generate a 18-residue peptide (CSP-18), which can work at a concentration much lower than that of CSP-21 [29,32]. SepM is identified in all the 10 strains compared in this study, although putative comC alleles are present only in the eight S. mutans strains, not in the S. sobrinus DSM 20742 and S. ratti DSM 20564. Multi-alignment of the ComC sequences shows clear variations among different S. mutans strains (Figure 4a). Genetic variation of ComC in S. mutans has been reported previously [33]. Interestingly, the C-terminal amino acid sequence “LGK” of ComC is absent in the ComC prepetides of S. mutans KK23 and AC4446, which have also been observed previously in other S. mutans strains by Allan et al. [33]. ATCC 25175 possesses a unique ComC sequence ended with “LGKIR” at its C-terminal. In addition to the variations at the carboxyl end, substitutions of single amino acid residues at different positions are also found.

Figure 4.

Alignment of ComC and ComS amino acid sequences. a) Alignment of ComC amino acid sequences identified in S. mutans species using CLUSTALX. Conserved residues are marked with “*” above the figure. The diversity in the ComC sequences have been verified by PCR experiments (data not shown). b) BlastP alignment of the ComS sequence of S. mutans (identical among the eight S. mutans strains) with that of S. ratti DSM 20564 (No ComS was identified in S. sobrinus). “+” stands for similar amino acid residues.

We have verified all the variants of comC revealed in this study by PCR experiments. Although Allan et al. pointed out that different comC alleles in some clinical strains of S. mutans exist but their products are functionally equivalent and there is no evidence of phenotype specificity [33], considering the complexity of phenotype evaluation, whether and how the variations found in this study may affect the natural genetic competence of these S. mutans strains requires further investigation.

The CSP-initiated activation of the response regulator ComE, through its cognate receptor kinase ComD, leads to the induction of competence through the alternative sigma factor ComX, and at the same time ComE directly induces a set of bacteriocin-related genes [28,30,34-38]. In our previous study focused on the comparison of the two-component signal transduction systems of these mutans streptococci strains, we have reported the complete missing of ComDE in S. ratti DSM 20564 and the low similarities of putative ComDE in S. sobrinus DSM 20742 to the ComDE of S. mutans strains [26]. Accordingly, no comC-like genes could be identified in S. ratti DSM 20564 and S. sobrinus DSM 20742. Thus, it can be inferred that S. ratti DSM 20564 and S. sobrinus DSM 20742 are totally different to the S. mutans strains regarding cellular functions including genetic competence associated with the ComABCDE system.

In S. mutans, no binding motif for ComE is present in the promoter region of ComX, suggesting that ComE is not a direct regulator of ComX, whereas a new peptide regulator system (ComSR) downstream of ComE that directly activates ComX has been identified by Mashburn-Warren et al. ComR activates the expression of the ComS, which is secreted, processed, and internalized through the peptide transporter OppD. The processed peptide, designated XIP (for sigma X-inducing peptide), modulates the activity of ComR, which in turn activates the expression of ComX. Deletion of comR or comS gene completely abolished the competence in S. mutans[39]. In this study, the ComSR regulating system is identified in most of the strains, except for S. sobrinus DSM 20742 which lacks the ComSR-coding genes. This well explains the fact that despite the presence of comX and the ‘late-competence genes’ we were not able to obtain the genetic competence state of S. sobrinus DSM 20742 (see discussion later in the “Variability and specificity in metabolic pathways and network” part). It is also worth to mention that the putative ComS ortholog found in S. ratti DSM 20564 is quite different to those of S. mutans strains, as shown in Figure 4b.

CSP-independent competence regulation system

It has been reported that a basal level of competence remains (referred as CSP-independent competence) after the deletion of comE from S. mutans, suggesting that the CSP-dependent regulation system is one of the several signaling pathways involved in ComX activation [34]. Indeed, under conditions of biofilm growth the HdrMR system, a novel two-gene regulatory system, has been shown to contribute to competence development through the activation of ComX by a yet unknown signal [40]. Moreover, microarray analysis revealed that both regulators, ComE and HdrR, activate a large set of overlapping genes [40,41]. Recently, Xie et al. identified in S. mutans another regulatory system, designated BsrRM, that primarily regulates bacteriocin-related genes but also affects the HdrMR system and thus indirectly contributes to competence development [42]. In this study, HdrR, the response regulator of the HdrMR system, is found neither present in S. ratti DSM 20564 nor in S. sobrinus DSM 20742. Furthermore, the response regulator BrsR of the BsrRM system is also absent in S. ratti DSM 20564, whereas S. sobrinus DSM 20742 lacks the complete BsrRM system. It’s also worth to mention that a competence damage-inducible protein CinA, which is regulated via ComX and has been proven to be related to DNA damage, genetic transformation and cell survival [43], is present in all strains.

Taking together, both the CSP-dependent and CSP-independent competence regulation systems in S. ratti DSM 20564 and especially in S. sobrinus DSM 20742 are very different to those of the S. mutans strains.

Distribution of bacteriocin-related proteins and antibiotic resistance-related proteins

Bacteriocin-related proteins

Bacteriocins are proteinaceous toxins produced by bacteria to kill or inhibit the growth of similar or closely related bacterial strain(s). Bacteriocins produced by mutans streptococci are named “mutacins”. As dental plaque, the dominating niche of mutans streptococci, is a multispecies biofilm community that harbors many microorganism species, mutans group strains have developed a variety of mutacins to inhibit the growth of competitors, such as mitis group streptococci [44-46]. In this study, information about known mutacins as well as mutacin-immunity proteins was collected from the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and Oralgen (http://www.oralgen.lanl.gov/) databases, as well as by searching for related publications. The collected protein sequences, as listed in Additional file 5, were used to blast against the proteomes of the 10 strains to see whether or not these known mutacins and mutacin-immunity proteins do exist in the mutans streptococci strains of this study. Distributions of identified mutacins and mutacin-immunity proteins are summarized in Table 4. Using this approach it is, however, not possible to identify any new types of mutacins.

Table 4.

Distribution of mutacins and mutacin immunity proteins in the 10 mutans streptococci strains

| S. mutans UA159 | S. mutans NN2025 | S. mutans 5DC8 | S. mutans KK21 | S. mutans KK23 | S. mutans AC4446 | S. mutans ATCC 25175 | S. mutans NCTC 11060 |

S. ratti |

S. sobrinus DSM 20742 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM 20564 | |||||||||||

|

Mutacin-SMB (lantibiotic mutacin) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

D822_07608 D822_07613 |

- |

[47,48] |

|

Mutacin-I (lantibiotic mutacin) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

[49,50] |

|

Mutacin-II (lantibiotic mutacin) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

[51] |

|

Mutacin-III (lantibiotic mutacin) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

[52] |

|

Mutacin-K8 (lantibiotic mutacin) |

- |

GI|290579849 GI|290579848 GI|290579850 |

- |

- |

D818_07928 D818_07933 D818_07938 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

[53] |

|

Mutacin-IV (NlmA) |

SMU.150 |

- |

D816_00655 |

D817_00675 |

D818_00659 |

- |

D820_00642 |

D821_00661 |

- |

- |

[54] |

|

Mutacin-IV (NlmB) |

SMU.151 |

- |

D816_00660 |

D817_00680 |

D818_00664 |

- |

D820_00647 |

D821_00666 |

- |

- |

[54] |

|

Mutacin-IV like (SMU.283) |

SMU.283 |

GI|290581209 |

D816_01135 |

D817_01285 |

D818_01099 |

D819_01148 |

D820_01321 |

D821_01193 |

D822_03404 |

- |

[8] |

|

Immunity protein of Mutacin-IV |

SMU.152 |

GI|290580110 |

D816_06832 |

D817_06998 |

D818_06649 |

D819_06637 |

D820_06850 |

D821_06847 |

D822_03264 |

D823_04636 |

[55,56] |

|

Mutacin-V (CipB) |

SMU.1914c |

GI|290579763 |

D816_08583 |

D817_08773 |

D818_08363 |

D819_07834 |

- |

- |

D822_03354 |

- |

[55,56] |

|

CipI, immunity protein of CipB (Mutacin-V) |

SMU.925 |

|

D816_04020 |

D817_04283 |

D818_04522 |

D819_04119 |

D820_04232 |

D821_04089 |

D822_03349 |

|

[55,56] |

|

Homolog of CipI |

SMU.1913c |

GI|290579764 |

D816_08578 |

D817_08768 |

D818_08358 |

D819_07829 |

|

|

|

D823_03992 |

[56] |

|

SMU.423 possible bacteriocin |

SMU.423 |

GI|290581063 |

D816_01775 |

D817_01930 |

D818_01847 |

D819_01823 |

D820_01975 |

D821_01862 |

|

D823_05348 |

[8] |

|

NlmT/ComA transporting ATPase |

SMU.286 SMU.1881c |

GI|290581206 GI|290579788 |

D816_01150 D816_08453 |

D817_01300 D817_08643 |

D818_01134 - |

D819_01163 D819_07724 |

D820_01336 - |

D821_01208 D821_08449 |

D822_01584 D822_08325 - |

D823_05343 D823_01400 |

[28,29] |

| NlmE/ComB accessory factor for NlmT | SMU.287 | GI|290581205 | D816_01155 | D817_01305 | D818_01139 | D819_01168 | D820_01341 | D821_01213 | D822_01589 | D823_05923 | [28,29] |

In the case that more than one paralogs were found, the most similar ortholog is marked in bold font.

Note: as a multi-function exporter, the entries of NlmTE(ComAB) have been shown in Table 3 and here again.

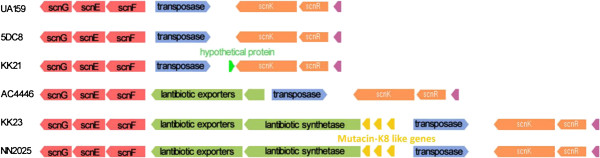

Diversity of Streptococcus bacteriocins has been reported previously [57,58]. The mutacin assortments among the 10 strains in this study also demonstrate certain variations. An interesting result is that in contrast to S. mutans strains and S. ratti DSM 20564, S. sobrinus DSM 20742 does not possess any genes coding for mutacin-like proteins. Mutacin-SMB has been identified in S. mutans and S. ratti previously [47,48]. In our study, mutacin-SMB cluster was only identified in S. ratti DSM 20564 comprising 7 genes, including the mutacin-coding genes smbA and smbB, as well as 5 mutacin-related genes (smbG- > D822_07603, smbT- > D822_07593, smbM- > D822_07578, smbF- > D822_07588, and smbM2- > D822_07598). Lantibiotic mutacins, mutacin-I [49], mutacin-II [51] and mutacin-III [52], are completely absent in the 10 mutans streptococci strains. However, three gene copies possibly encoding the precursor of the lantibiotic mutancin mutacin-K8 are identified in the S. mutans strains KK23 and NN2025. Mutacin-K8 is an ortholog of the bacteriocin Streptococcin A-FF22 identified in group-A streptococci [59], and its production system has previously also been identified in the S. mutans strain K8 [53]. By carefully examining the genes surrounding mutacin-K8 precursor genes the gene cluster coding for a complete mutacin-K8 production system is also revealed in the strains KK23 and NN2025 (Figure 5). A partial ortholog of the mutacin-K8 production system is found in S. mutans UA159, 5DC8 and KK21, with only genes responsible for the immunity (scnFEG) left behind. Orthologous genes coding for a part of the mutacin-K8 production system are also found in S. mutans AC4446, consisting of only scnFEG, scnT (coding a lantibiotic exporter) and a part of scnM (coding the lantibiotic synthetase). Since a gene encoding ISSmu2-type transposase is found to be located upstream of mutacin-K8 precursor genes, we infer that the variety of mutacin-K8 production system in S. mutans strains studied here is highly possible to be caused by transposase actions.

Figure 5.

Cluster structure of the mutacin-K8 production system across six S. mutans strains. The ORFs colored in yellow are the possible mutacin-K8 precursor genes. scnGEF: bacteriocin related ABC element; possible immunity system; scnK: histidine kinase of two component system; scnR: response regulator of two component system (Note: mutacin-K8 production system was failed to be identified in S. mutans NCTC 11060, S. mutans ATCC 25175, S. ratti DSM 20564 and S. sobrinus DSM 20742).

Mutacin-IV, nonlantibiotic bacteriocins coded by nlmA/B (SMU.150/151, Note: hereinafter whenever needed/possible the locus_tag of the reference strain S. mutans UA159 is given for convenience) was discovered first in S. mutans UA140 to be active against the mitis group streptococci [54]. In this study, nlmA/B are found to be present in six of the S. mutans strains, including UA159, 5DC8, KK21, KK23, ATCC 25175 and NCTC 11060, but not in S. mutans NN2025 and AC4446, nor in S. ratti DSM 20564 and S. sobrinus DSM 20742. On the other hand, the immunity protein for mutacin-IV (SMU.152), is identified in all strains, consistent with the fact that no inhibition phenomenon has been observed yet among different mutans streptococci strains. A mutacin-IV like protein found before in the strain UA159 (SMU.283) is identified in all strains except for S. sobrinus DSM 20742.

Mutacin-V, another nonlantibiotic peptide coded by cipB (SMU.1914) is found, in addition to S. sobrinus DSM 20742, also absent in the S. mutans strains ATCC 15175 and NCTC 11060. There are two homologs of mutacin-V immunity protein in S. mutans UA159, namely CipI (SMU.925) and SMU.1913 [8,60]. These two immunity proteins share a sequence identity of 82%. However, it has been reported that though very likely co-transcribed with cipB, SMU.1913 cannot prevent CipB-caused cell lysis in S. mutans UA159, and the key immunity factor of mutacin-V has been supposed to be CipI (SMU.925) rather than SMU.1913 [60]. All the 10 strains including S. sobrinus DSM 20742 possess at least one orthologous gene encoding one of the two mutacin-V immunity proteins. Based on the similarity scores S. mutans NN2025 does not have an ortholog of CipI (SMU.925), but it possesses an ortholog (GI|290579764) of SMU.1913, which is possibly co-transcribed with GI|290579764, the cipB ortholog in S. mutans NN2025. Furthermore, the only putative immunity protein D822_3349 in S. ratti DSM 20564 shows very close similarities to SMU.925 (61%) and SMU.1913 (56%) and is possibly co-transcribed with D822_03354, the CipB ortholog in S. ratti DSM 20564. From these results, we suppose that SMU.1913, which is co-transcribed with cipB (SMU.1914), might be the ancestor gene coding for the mutacin-V immunity factor. The additional copy, like SMU.925 in S. mutans UA159, might be generated by duplication action and evolved as the dominant immunity factor in some of the mutans streptococci strains.

Furthermore, a possible nonlantibiotic bacteriocin peptide (SMU.423) is found to be present in all strains except for S. ratti DSM 20564. Putative ComAB, which has been proved to be the transporter complex of mutacin IV in S. mutans[28], are identified in all strains, supporting the suggestion that ComAB might function as a common transporter for multi-type nonlantibiotic bacteriocins rather than merely for mutacin IV. Moreover, an additional paralog of ComA is present in most of the strains except for S. mutans KK23 and S. mutans ATCC 25175.

To summarize, a differed distribution of mutacin/bacteriocin encoding genes accompanied with a high conservation of genes coding for mutacin-immunity proteins are revealed for the 10 mutans streptococci strains/species. The conservation of mutacin immunity proteins apparently plays an important role for the survival of mutans streptococci strains under a bacteriocin-rich environment.

Antibiotic resistance-related proteins

Bacteria and other microorganisms that cause infections are remarkably resilient and can develop ways to survive drugs meant to kill or weaken them. Antibiotic resistance can be a result of horizontal gene transfer [61], and also of unlinked point mutations in the pathogen genome at a rate of about 1 in 108 per chromosomal replication [62]. The antibiotic action against the pathogen can be seen as an environmental selective pressure and bacteria which have developed mutations allowing them to survive will live on to reproduce. They will then pass this trait to their offsprings, which will result in the evolution of fully resistant colonies. Putative resistance-related genes are identified and listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Distribution of antibiotic resistance-related proteins

| Name | Putative function | S. mutans UA159 | S. mutans NN2025 | S. mutans 5DC8 | S. mutans KK21 | S. mutans KK23 | S. mutans AC4446 | S. mutans ATCC 25175 | S. mutans NCTC 11060 | S. ratti DSM 20564 | S. sobrinus DSM 20742 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

UppP |

Putative bacitracin resistant |

SMU.244 |

GI|290581239 |

D816_00960 |

D817_01110 |

D818_00974 |

D819_00998 |

D820_01146 |

D821_00986 |

D822_05517 |

D823_09307 |

|

BceA |

Bacitracin resistant ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

SMU.1006 |

GI|290580542 |

D816_04484 |

D817_04663 |

D818_04902 |

D819_04489 |

D820_04607 |

D821_04449 |

D822_02154 |

D823_04551 |

|

BceB |

Bacitracin resistant ABC transporter permease protein |

SMU.1007 |

GI|290580541 |

D816_04489 |

D817_04668 |

D818_04907 |

D819_04494 |

D820_04612 |

D821_04454 |

D822_02159 |

D823_04556 |

|

DacF |

Penicillin binding protein; Penicillin sensitive protein |

SMU.75 |

GI|290579588 |

D816_00335 |

D817_00355 |

D818_00354 |

D819_00260 |

D820_00330 |

D821_00310 |

D822_07803 |

D823_05036 |

|

Pbp2X |

Penicillin-binding protein 2X; Penicillin sensitive protein |

SMU.455 |

GI|290581039 |

D816_01905 |

D817_02153 |

D818_01967 |

D819_01954 |

D820_02095 |

D821_01964 |

D822_00802 |

D823_06528 |

| |

metallo-beta-Lactamase superfamily protein; beta-Lactam resistance; |

SMU.368c |

GI|290581108 |

D816_01525 |

D817_01680 |

D818_01583 |

D819_01608 |

D820_01711 |

D821_01583 |

D822_04346 |

D823_00655 |

| |

beta-Lactamase family protein; beta-Lactam resistance; |

SMU.400 |

GI|290581086 |

D816_01660 |

D817_01815 |

D818_01732 |

D819_01708 |

D820_01860 |

D821_01747 |

D822_05706 |

D823_03675 |

|

YqgA |

beta-Lactam resistance; |

SMU.1444c |

GI|290580186 |

D816_06482 |

D817_06653 |

D818_06314 |

D819_06285 |

D820_06483 |

D821_06502 |

D822_08877 |

D823_08387 |

| |

Lactamase_B; |

SMU.1515 |

GI|290580115 |

D816_06807 |

D817_06973 |

D818_06624 |

D819_06612 |

D820_06825 |

D821_06822 |

D822_03289 |

D823_04661 |

|

beta-Lactam resistance; | |||||||||||

|

MurN |

beta-Lactam resistance factor MurN |

SMU.716 |

GI|290580807 |

D816_03100 |

D817_03358 |

D818_03627 |

D819_03104 |

D820_03315 |

D821_03199 |

D822_00265 |

D823_09452 |

|

MurM |

beta-Lactam resistance factor murM; |

SMU.717 |

GI|290580806 |

D816_03105 |

D817_03363 |

D818_03632 |

D819_03109 |

D820_03320 |

D821_03204 |

D822_00260 |

D823_09457 |

| |

Macrolide-efflux protein |

|

GI|290581182 |

|

|

D818_01269 |

D819_01313 |

|

|

|

|

| |

Putative multidrug resistance ABC transporter |

|

GI|290581181 |

|

|

D818_01274 |

D819_01318 |

|

|

|

|

|

VanW |

Vancomycin b-type resistance protein |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D822_01634 |

|

| |

Putative multidrug resistance protein b |

SMU.745 |

GI|290580783 |

D816_03220 |

D817_03478 |

D818_03732 |

D819_03234 D819_09750 |

D820_03442 |

D821_03314 |

D822_00530 |

D823_08347 |

|

PmrA |

Putative multidrug resistance efflux pump |

SMU.1611c |

GI|290580030 |

D816_07242 |

D817_07403 |

D818_07009 |

D819_07037 |

D820_07260 |

D821_07242 |

D822_07918 |

D823_02317 |

|

YitG |

Putative multidrug resistancepermease |

SMU.1286c |

GI|290580299 |

D816_05764 |

D817_05958 |

D818_02360 |

D819_05785 |

D820_05818 |

D821_05850 |

D822_01559 |

|

| Putative multidrug resistanceABC transport | SMU.905 | GI|290580642 | D816_03940 | D817_04208 | D818_04447 | D819_03949 | D820_04157 | D821_04009 | D822_09885 | D823_08492 |

The S. mutans species is known to be intrinsically resistant to bacitracins produced by Bacillus subtilis. We confirmed this by testing all the 10 strains with a bacitracin-E-test (data not shown). All strains including S. ratti DSM 20564 and S. sobrinus DSM 20742 had a minimum inhibitory concentration between 128 and >256 μg/l. In fact, this antibiotic is used to isolate mutans-streptococci from highly heterogeneous oral microflora. It has been reported that bceABRS (also named as mbrABCD) system, encoding a two component signal transduction system and an ABC-transporter, is required for bacitracin resistance in S. mutans[63,64]. As expected, ortholog of bceABRS system is found to be present in all strains. Furthermore, an ortholog of a putative bacitracin resistance protein UppP (SMU.244, undecaprenyl-diphosphatase) is present in all strains. It has been proved that overexpression of UppP in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis results in bacitracin resistance [65,66]. However, the function of UppP in bacitracin resistance in mutans streptococci has not yet been investigated. Based on its conservation in all strains studied here, we suppose that UppP might play an important role in bacitracin resistance for mutans streptococci species as well.

Two penicillin-binding proteins (SMU.75 and SMU.455) are identified in all strains, indicating that they are potentially all susceptible to penicillin. Phenotypically all strains were tested to be susceptible to penicillin (data not shown). On the other hand, all the strains possess orthologs of SMU.368c, SMU.400, SMU.1444c and SMU.1515, which are homologs to beta-lactamases (EC 3.5.2.6), as well as orthologs of two so called beta-lactam resistance factors (SMU.716, SMU.717). Thus, all the strains are potentially capable of resistance against beta-lactam antibiotics. Orthologs of macrolide-efflux transporter proteins, as coded by GI|290581182 and GI|290581181 in S. mutans NN2025, are found to be also present in S. mutans 5DC8 and S. mutans KK21. A vancomycin b-type resistance-associated protein (D822_01634) is uniquely present in S. ratti DSM 20564, but our phenotypic testing showed as expected that S. ratti DSM 20564 is susceptible to vancomycin. Furthermore, several putative multidrug resistance-associated proteins (SMU.745, SMU.1611c and SMU.905 except for SMU.1286c) are found to be present in all strains.

Oxidative stress defense systems in mutans streptococci

For protection against reactive oxygen species (such as O2-, H2O2, HO·) or adaptation to oxidative stresses aerobes and facultative anaerobes have evolved efficient defense systems, comprising an array of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), Dps-like peroxide resistance protein, alkylhydroperoxide reductase (AhpCF), glutathione reductase, and thiol reductase, which have been identified in many bacterial species.

Although the first genome sequence of S. mutans UA159 has already been published in 2002, the oxidative stress defense systems in the group of mutans streptococci have not yet been systematically discussed. By searching for known antioxidant systems in the genomes of the sequenced mutans streptococci strains of this study, we obtained an overview of putative oxidative defense systems in these mutans streptococci strains/species which are composed of superoxide dismutase (SOD), AhpF/AhpC system, Dpr, thioredoxin system and glutaredoxin system, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Distribution of oxidative stress resistance systems

| Class | Name | Function | S. mutans UA159 | S. mutans NN2025 | S. mutans 5DC8 | S. mutans KK21 | S. mutans KK23 | S. mutans AC4446 | S. mutans ATCC 25175 | S. mutans NCTC 11060 | S. ratti DSM 20564 | S. sobrinus DSM 20742 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SOD |

Sod |

Superoxide dismutase |

SMU.629 |

GI|290580884 |

D816_02695 |

D817_02943 |

D818_03247 |

D819_02714 |

D820_02900 |

D821_02804 |

D822_02694 |

D823_08152 |

| |

|

3′-Phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate phosphatase |

SMU.1297 |

GI|290580288 |

D816_05819 |

D817_06013 |

D818_02305 |

D819_05840 |

D820_05873 |

D821_05905 |

D822_08440 |

D823_09052 |

|

AhpF/AhpC system |

AhpC |

Alkyl hydroper oxide reductase, subunit C |

SMU.764 |

GI|290580768 |

D816_03290 |

D817_03548 |

D818_03807 |

D819_03314 |

D820_03512 |

D821_03389 |

D822_08028 |

- |

| AhpF (Nox1) |

Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, subunit F |

SMU.765 |

GI|290580767 |

D816_03295 |

D817_03553 |

D818_03812 |

D819_03319 |

D820_03517 |

D821_03394 |

D822_08023 |

- |

|

|

Dpr |

Dpr |

Peroxide resistance protein / iron binding protein |

SMU.540 |

GI|290580957 |

D816_02305 |

D817_02548 |

D818_02835 |

D819_02354 |

D820_02520 |

D821_02374 |

D822_04226 |

D823_02352 |

|

Thioredoxin system |

TrxB |

Thioredoxin reductase (NADPH) |

SMU.463 |

GI|290581031 |

D816_01940 |

D817_02188 |

D818_02007 |

D819_01989 |

D820_02130 |

D821_01999 |

D822_06878 |

D823_01947 |

| TrxB |

Thioredoxin reductase |

SMU.869 |

GI|290580673 |

D816_03785 |

D817_04038 |

D818_04292 |

D819_03804 |

D820_04002 |

D821_03854 |

D822_03499 |

D823_01550 |

|

| TrxA |

Thioredoxin |

SMU.1869 |

GI|290579800 |

D816_08398 |

D817_08588 |

D818_08193 |

D819_07664 |

D820_08390 |

D821_08394 |

D822_08270 |

D823_06913 |

|

| TrxH |

Thioredoxin family protein |

SMU.1971c |

GI|290579712 |

D816_08848 |

D817_09038 |

D818_08623 |

D819_08094 |

D820_08775 |

D821_08804 |

D822_07458 |

D823_08552 |

|

| |

Thioredoxin family protein |

SMU.1169c |

GI|290580401 |

D816_05229 |

D817_05413 |

D818_05692 |

D819_05219 D819_05259 |

D820_05307 |

D821_05309 |

D822_06958 |

- |

|

| Tpx |

Thiol peroxidase |

SMU.924 |

GI|290580628 |

D816_04015 |

D817_04278 |

D818_04517 |

D819_04114 |

D820_04227 |

D821_04084 |

D822_03359 |

D823_07595 |

|

| Glutaredoxin system | GshAB |

Glutathione biosynthesis bifunctional protein |

SMU.267c |

GI|290581223 |

D816_01065 |

D817_01215 |

D818_01054 |

D819_01078 |

D820_01251 |

D821_01091 |

D822_01287 |

D823_06703 |

| GshR |

Glutathione reductase |

SMU.838 |

GI|290580702 |

D816_03640 |

D817_03893 |

D818_04147 |

D819_03659 |

D820_03857 |

D821_03709 |

D822_01904 |

D823_04976 |

|

| GshR |

Glutathione reductase |

SMU.140 |

- |

D816_00620 |

D817_00640 |

D818_00624 |

- |

D820_00607 |

D821_00626 |

D822_06143 |

- |

|

| NrdH | Glutaredoxin | SMU.669c | GI|290580848 | D816_02885 | D817_03143 | D818_03447 | D819_02894 | D820_03090 | D821_03009 | D822_02899 | D823_05398 |

SOD, which catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, is an important antioxidant defense in nearly all cells exposed to oxygen [67]. SOD is found in all strains of this study. Catalase, which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, is not found in any of the mutans streptococci strains of this study. It is known that although most streptococci can grow in the presence of air, they do not possess a catalase, implying that hydrogen peroxide defense mechanism, by which lactic acid bacteria established their growth in air, are very different to those of aerobes. It has been reported that both the bi-component peroxidase system AhpF/AhpC and Dps-like peroxide resistance protein confer tolerance to oxidative stress in S. mutans[68].

The AhpF/AhpC system catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of organic hydroperoxides and/or H2O2 to their respective alcohol and/or H2O. Both AhpF and AhpC are present in all S. mutans strains of this study and in S. ratti DSM 20564, but are absent in S. sobrinus DSM 20742. The natural missing of AhpF and AhpC in S. sobrinus indicates that AhpF/AhpC system is not an essential peroxide tolerance system for some mutans streptococci species. While studying a ahpF and ahpC double deletion mutant of S. mutans, Higuchi et al. [69] found that the mutant still showed the same level of peroxide tolerance as did the wild-type strain that led them to the finding of the dpr gene, which encodes a ferritin-like iron-binding protein involved in oxygen tolerance by limiting the nonenzymatic hydroxyl radical synthesis via iron-catalyzed ‘Fenton reaction’ in S. mutans. Their further studies on the biological function of dpr found that dpr gene from S. mutans chromosome was capable of complementing an alkyl hydroperoxide reductase-deficient mutant of E. coli, as well as complementing the defect in peroxidase activity caused by the deletion of ahpF/ahpC in S. mutans, indicating that dpr plays an indispensable role in oxygen tolerance of S. mutans[68,70]. Dpr homologs were found in all strains as expected by the supposed essential function of dpr gene in oxygen tolerance.

Thioredoxins are a class of small redox mediator proteins known to be present in all organisms. They are involved in many important biological processes, including redox signaling. Thioredoxins are kept in the reduced state by the flavor enzyme thioredoxin reductase in a NADPH-dependent reaction [71]. They act as electron donors to many proteins including thiol peroxidases [72]. Thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase and thiol peroxidase, the components of thioredoxin system, are identified in all the strains of this study. Two putative thioredoxin reductases (SMU.463 and SMU.869) are found in all strains/species. It has been reported that in some species thioredoxin reductases have been evolved to be activated by both NADPH and NADH [73]. We speculate that SMU.463 and SMU.869 might have been evolved to have different preferences to NADPH and NADH (SMU.463 and SMU.869 shares less than 20% similarities). If it holds true, this could be advantageous for these mutans streptococci, as the extra amount of NADH produced from glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway under anaerobic conditions could be directly used for oxidative stress resistance. Thioredoxin (SMU.1869) and two thioredoxin family proteins (SMU.1971c and SMU.1169c) are found to be present in nearly all strains, except for S. sobrinus DSM 20742, which lacks any ortholog of SMU1169c. An ortholog of a thiol peroxidase-coding gene (tpx) is identified in all strains.

Glutaredoxins share many functions of thioredoxins but are reduced by glutathione (L-γ-glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine, GSH) rather than by a specific reductase. This means that glutaredoxins are oxidized by their corresponding substrates, and reduced non-enzymatically by GSH [74]. Oxidized glutathione (GSSG) is then regenerated by glutathione reductase. Together, these components comprise the glutathione system [75]. GSH is a well-characterized antioxidant in eukaryotes and Gram-negative bacteria, where it is synthesized by the sequential action of two enzymes, γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS) and glutathione synthetase (GS). Among Gram-positive bacteria only a few species contain GSH. It has been reported that streptococci lack the moderate-to-high levels of intracellular glutathione normally found in Gram-negative bacteria [76]. Using Streptococcus agalactiae as a model, it has been discovered that in GSH-containing Gram-positive bacteria GSH synthesis is catalyzed by one bifunctional protein, γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase-glutathione synthetase (γ-GCS-GS), encoded by one gene, gshAB. Homologs of γ-GCS-GS have been identified in the genomes of 19 mostly studied Gram-positive bacteria, including S. mutans[77]. All components of the glutathione system were identified in all the 10 strains of this study. Several S. mutans strains, namely UA159, 5DC8, KK21, KK23, ATCC 25175, and NCTC 11060, as well as S. ratti DSM 20564, possess two glutathione reductase orthologs (SMU.140 and SMU.838). This could possibly convey these strains certain advantages in the re-generation of GSH from GSSG, which in turn would be helpful for oxidative resistance.

In addition, 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate phosphatase activity has recently been reported to be required for superoxide stress tolerance in S. mutans[78]. Putative 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate phosphatase coding genes were identified in all strains (Table 6).

Variability and specificity in metabolic pathways and network

In order to reveal the metabolic variability of the mutans streptococci systematically, we have reconstructed and analyzed the genome-scale metabolic networks of all the strains sequenced with the method proposed by Ma and Zeng [79] and an updated database [79]. All annotated protein sequences having EC numbers are considered for the network reconstruction. From the functional annotation discussed above, total EC numbers identified in the 10 strains are very close to each other, as shown in Table 7. A summary of the total numbers of the reactions and metabolites in each of the reconstructed metabolic networks is shown in Table 7, and all the constructed metabolic networks are provided in Additional file 6 in *.cys format which can be opened with Cytoscape [80], a software for visualization and analysis of biological networks. The sizes of the constructed metabolic networks of the eight S. mutans strains are very close to each other, with UA159, NN2025, AC4446, 5DC8 and KK21 having almost exactly the same size, and the networks of KK23, ATCC 25175 and NCTC 11060 being merely about 2% larger. While the size of the metabolic network of S. ratti DSM 20564 is comparable to those of the S. mutans strains, the metabolic network of S. sobrinus with 833 reactions and 853 metabolites is the smallest one, which have 62 less reactions and 60 less metabolites compared to the largest one of S. mutans NCTC 11060 (895 reactions and 913 metabolites).

Table 7.

Compositions of the established metabolic networks of the 10 mutans streptococci strains

| Strain | EC numbers | Reactions | Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

|

S. mutans UA159 |

454 |

875 |

893 |

|

S. mutans NN2025 |

450 |

874 |

892 |

|

S. mutans 5DC8 |

453 |

875 |

893 |

|

S. mutans KK21 |

453 |

875 |

893 |

|

S. mutans KK23 |

452 |

893 |

911 |

|

S. mutans AC4446 |

449 |

874 |

893 |

|

S. mutans ATCC 25175 |

453 |

891 |

911 |

|

S. mutans NCTC 11060 |

456 |

895 |

913 |

|

S. ratti DSM 20564 |

435 |

888 |

893 |

| S. sobrinus DSM 20742 | 434 | 833 | 853 |

Despite the comparable network sizes, however, all the strains possess or lack certain reactions/metabolites, as revealed by detailed comparative analyses. Using the metabolic network of S. mutans UA159 as reference, the presence and absence of reactions in each of the strains/species compared are discovered and mapped into sub-pathways based on the KEGG pathway classification (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). As a result, among the 416 sub-pathways defined in the KEGG pathway database 46 sub-pathways demonstrated certain variations between the strains/species, as summarized in Additional file 7.

A key feature of the oral environment is that the nutrients available to the oral bacteria are always fluctuating between abundance and famine associated with human diet. Thus, the ability to quickly acquire and metabolize carbohydrates to produce energy and precursors for biosynthesis is essential for the survival of all oral bacteria. Due to their key roles in carbohydrates metabolism and energy production, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, TCA cycle and pyruvate metabolism pathways are generally considered to be highly conserved among these oral bacteria. Although mutans streptococci strains/species are closely related species as revealed by phylogenetic tree analysis in this study (Figure 1), differences in the central carbon metabolic pathways are found as shown in Figure 6.

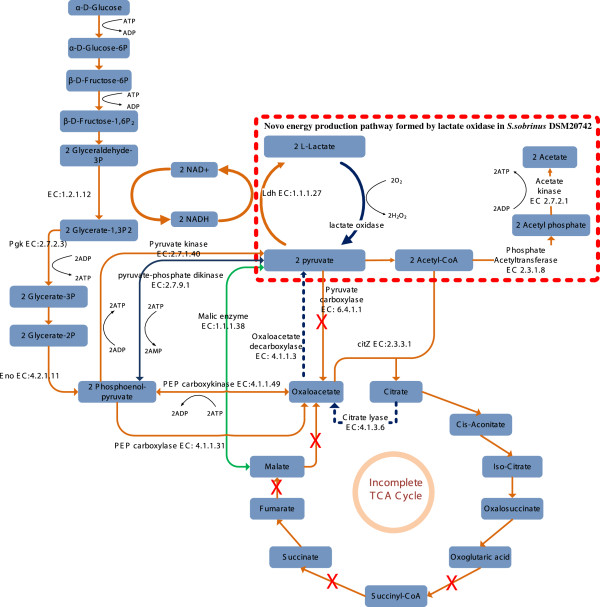

Figure 6.

Central metabolism pathways of mutans streptococci. The orange lines represent enzyme reactions conserved across the mutans streptococci strains compared in this study, whereas the blue lines represent enzyme reactions specifically present (solid line) or absent (dashed line) in S. sobrinus DSM 20742. Reaction catalyzed by NAD+-specific malic enzyme (EC: 1.1.1.38) (green line) is absent in S. mutans NN2025 and S. mutans AC4446. Pyruvate-phosphate dikinase, catalyzing the interconversion of PEP and pyruvate (black line), is uniquely present in S. ratti DSM 20564.

Facultative anaerobes such as lactic acid bacteria including Streptococcus lack cytochrome oxidases required for energy-linked oxygen metabolism and energy (in the form of ATP) required for survival and growth are generated by substrate level phosphorylation in the glycolysis pathway [69]. L-lactate oxidase (D823_06598) with a similarity of 73% to YP_003064450.1 (accession number) of Lactobacillus plantarum JDM1 and lactate oxidase (D823_06595) with a similarity of 65% to ZP_09448656.1 (accession number) of Lactobacillus mali KCTC 3596, are found to be uniquely present in S. sobrinus DSM 20742. These two enzymes catalyze the reaction of L-Lactate + O2= > Pyruvate + H2O2 and/or D-Lactate + O2= > Pyruvate + H2O2. It has been reported that in S. pneumoniae concerted action of lactate oxidase and pyruvate oxidase forms a novel energy-generation pathway by converting lactate acid to acetic acid under aerobic growth conditions [81]. Because there is no pyruvate oxidase identified in S. sobrinus DSM 20742, the function of the lactate oxidases in S. sobrinus DSM 20742 should be different to that of S. pneumoniae. By a close examination we hypothesize that lactate oxidase, together with pyruvate dehydrogenase, phosphate acetyl transferase and acetate kinase, could form a novel energy production pathway to convert lactate acid to acetate and simultaneously produce one additional ATP, as depicted Figure 6. By doing so, the lactate oxidases of S. sobrinus DSM 20742 could also play a role in consuming lactate to regulate pH, which would be an advantage for S. sobrinus DSM 20742 in resistance to acid stress. In addition, this pathway could replenish Acetyl-CoA, an important intermediate for the biosynthesis of fatty acids and amino acids. This is for the first time that such an energy production pathway is proposed in Streptococcus species. Furthermore, lactate oxidase and lactate dehydrogenase could form a local NAD+ regeneration system, which would be certainly advantageous to S. sobrinus DSM 20742 under aerobic growth conditions. Moreover, it is known that mutans group streptococci and the mitis group streptococci are competitors, with S. mutans producing mutacins to kill the mitis group streptococci and the mitis group streptococci in turn produce H2O2 to kill mutans group streptococci [16,82]. Favored by possessing the lactate oxidases, S. sobrinus DSM 20742 has the potential ability of producing H2O2 to kill not only competitors (oxygen sensitive S. mutans, oral anaerobes) but also macrophages [83], and defend its ecological niche. The unique presence of lactate oxidases in S. sobrinus DSM 20742 was verified by PCR experiments as shown in Additional file 8. Later, we also found that another S. sobrinus strain AC153 also harbors homologous genes of lactate oxidase, suggesting that lactate oxidase may be conserved and play an important role in S. sobrinus. In the effort to clarify the functionality of lactate oxidase we tried to knock out the two genes encoding the two enzymes by PCR ligation mutagenesis according to the method of Lau PC et al. (2002). We applied different transformation methods (two natural transformation methods and two electroporation methods) but were failed to obtain the desired recombinants. Then, to find out if S. sobrinus DSM 20742 is able to enter genetic competence state at all, we tried to transform S. sobrinus with plasmids replicative in other Streptococcus spp. like pDL278 (Spr, pAT18 Emr, with suicide vector pFW5 Spr in both circular and linearized forms but could not obtain the transformants. Therefore, it is clear that the genetic competence behavior of S. sobrinus DSM 20742 is very different to that of S. mutans, attributing very likely to the lacking of the genes comSR and comC.

In contrast to the unique harboring of lactate oxidases in S. sobrinus DSM 20742, citrate lyase (EC 4.1.3.6), which catalyzes the cleavage of citrate into oxaloacetate and acetate, and oxaloacetate decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.3), catalyzing the irreversible decarboxylation of oxaloacetate to pyruvate and CO2, are not found in S. sobrinus DSM 20742, as shown in Figure 6 by the blue dotted lines. It has been reported that citrate lyase functions as a key enzyme in initiating the anaerobic utilization of citrate by a number of bacteria, further catabolism of oxaloacetate formed taking place either by decarboxylation or by reduction. In some organisms, oxaloacetate is decarboxylated to pyruvate by oxaloacetate decarboxylase, which is also induced in the presence of citrate. The two enzymatic reactions, which occur sequentially, constitute the ‘citrate fermentation pathway’ [84]. The absence of citrate lyase and oxaloacetate decarboxylase implies that S. sobrinus DSM 20742 might lacks the ability in anaerobic utilization of citrate as a substrate. The disadvantages of S. sobrinus DSM 20742 in citrate utilization could be offset by the novel energy production pathway from lactate to acetate proposed above.