Abstract

The protective efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG can be markedly augmented by stable integration of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genomic region RD1. BCG complemented with RD1 (BCG::RD1) encodes nine additional proteins. Among them, 10-kDa culture filtrate protein (CFP-10) and ESAT-6 (6-kDa early secreted antigenic target) are low-molecular-weight proteins that induce potent Th1 responses. Using pools of synthetic peptides, we have examined the potential immunogenicity of four other RD1 products (PE35, PPE68, Rv3878, and Rv3879c). PPE68, the protein encoded by rv3873, was the only one to elicit gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-producing cells in C57BL/6 mice infected with M. tuberculosis. Anti-PPE68 T cells were predominantly raised against an epitope mapped in the N-terminal end of the protein. Importantly, inactivation of rv3873 in BCG::RD1 did not modify CFP-10 and ESAT-6 secretion. Moreover, the generation of IFN-γ responses to these antigens following immunization with BCG::RD1 was independent of PPE68 expression. Taken together, these results show that PPE68 is an immunogenic product of the RD1 region, which does not interfere with the secretion and immunogenicity of CFP-10 and ESAT-6.

RD1 has been identified as a major region of difference between the attenuated mycobacterial strains Mycobacterium bovis BCG and M. microti, compared to pathogenic species such as M. bovis and M. tuberculosis (6, 9, 12, 16). The RD1 deletion disrupts nine coding sequences in BCG (13), removing entirely the genomic fragment from rv3872 to rv3879c and cutting off the 3′ end of rv3871. Among the lost genes are rv3874 (esxB) and rv3875 (esxA), the coding sequences for 10-kDa culture filtrate protein (CFP-10) and ESAT-6 (6-kDa early secreted antigenic target). Besides the esxB-esxA tandem, RD1 inactivates two sets of genes located directly upstream and downstream (rv3872 to rv3873 and rv3876 to rv3879c) that are thought to encode a secretion apparatus dedicated to the export of CFP-10 and ESAT-6 (17).

The protective efficacy of BCG against experimental tuberculosis is significantly improved by stable insertion of RD1, as shown by the reduced dissemination of M. tuberculosis in mice and guinea pigs vaccinated with BCG::RD1 knockin constructions (BCG::RD1) (17). Several factors might account for this enhanced level of protection. First, as BCG::RD1 bacilli persist significantly longer than BCG in vivo (16), the antigenic stimulation of the host immune system by mycobacterial antigens is likely to be more efficient with the recombinant vaccine. Second, BCG::RD1 induces the generation of potent Th1 responses specific for ESAT-6. Vaccination experiments using an ESAT-6 subunit vaccine have demonstrated that immune responses raised against this antigen protect mice against tuberculosis, although not better than BCG (4). Our observation that the increased protection conferred by BCG::RD1 over BCG correlates with ESAT-6 export further indicates that the route of delivery for ESAT-6 is crucial for optimal immunogenicity (17). Given the central role of this antigen for induction of Th1 responses, it appears essential to characterize the contribution of each of the RD1 products to the secretion and presentation of ESAT-6 to the host immune system.

Besides the ESAT-6 gene, the RD1 deletion in BCG removes entirely seven genes coding for potential antigens. CFP-10 is highly immunogenic in humans infected with M. tuberculosis (2, 3) and in cattle infected with M. bovis (1, 14). There is no evidence that the putative chaperone Rv3876 and the integral membrane protein Rv3877 are antigenic. However, cellular responses directed against Rv3872 (PE35), Rv3873 (PPE68), Rv3878, and Rv3879c were detected in calves infected with M. bovis (8, 14). Although weak compared to the skin reaction elicited by ESAT-6 and CFP-10, a delayed-type hypersensitivity response to PPE68 was observed in guinea pigs infected with M. tuberculosis (7), suggesting that PPE68 may be a significant immunogenic component of RD1. This hypothesis is supported by observations that other members of the PPE protein family elicit immune responses in human tuberculous patients and are protective against experimental tuberculosis in mouse models of infection (10, 18, 20). The study of the immunogenicity of PPE68 is nevertheless hampered by the nonspecific reactivity of nontuberculous animals and humans, possibly due to extensive sequence homology of PPE68 with PPE proteins expressed by environmental mycobacteria (7).

To optimize the design of recombinant BCG vaccines, it is essential to define whether the RD1 products contribute to the immunogenicity of this region, either directly or by mediating the export of the dominant antigens CFP-10 and ESAT-6. In this study, we have examined whether PE35, PPE68, Rv3878, and Rv3879c elicit Th1-oriented immune responses in a C57BL/6 mouse model of infection with M. tuberculosis. Using an immunodominant T-cell epitope mapped in PPE68, we could demonstrate that PPE68 is an RD1 component of significant immunogenicity that does not interfere with the secretion and presentation of CFP-10 and ESAT-6 to the host immune system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacteria.

BCG Pasteur 1173P2 and H37Rv were from stocks held at the Institut Pasteur, Paris, France. The RD1-2F9 construct has been previously described (17). The Rv3873 knockout (ko) construct was obtained by inserting an apramycin resistance cassette into the rv3873 gene on RD1-2F9. Electrocompetent cells for M. bovis BCG Pasteur 1173P2 were prepared from 400 ml of a 10-day-old Middlebrook 7H9 culture. Bacilli were harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 20 min at 16°C, washed with H2O at room temperature, and resuspended in 1 to 2 ml of 10% glycerol at room temperature after recentrifugation. Aliquots (250 μl) of bacilli were mixed with the respective cosmids and electroporated using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (2.5 kV; 1,000 Ω). Bacilli were resuspended in medium and left overnight at 37°C. Transformants were selected on Middlebrook 7H11 medium (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) supplemented with oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase and hygromycin (50 μg/ml) and apramycin (50 μg/ml). Antibiotic-resistant colonies appearing after 3 weeks were analyzed for the presence of the integrated vector by PCR, using primers specific for RD1 encoded genes.

Animals and immunization procedures.

Six-week-old female C57BL/6 or SCID mice (Charles Rivers, L'arbresle, France) were housed in specific-pathogen-free animal facilities of the Institut Pasteur. For immunization studies, mycobacteria were grown in Middlebrook 7H9-ADC medium supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 and appropriate antibiotics. Bacteria were harvested by low-speed centrifugation and washed once with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) before resuspension in 1 to 5 ml of the same buffer. The bacteria were then sonicated briefly and allowed to stand for 2 h to allow residual aggregates to settle. The bacterial suspensions were then aliquoted and frozen at −80°C. A single aliquot was defrosted for quantification of each vaccine lot. Mice were immunized subcutaneously at the base of the tail with 105 CFU of the different strains.

Antigens and peptides.

Bovine purified protein derivative (PPD) tuberculin was obtained from the Veterinary Laboratories Agency (Weybridge, United Kingdom). Concanavalin A (ConA) was from Sigma (St Louis, Mo.). Synthetic peptides (20-mer with a 12-residue overlap) spanning the PE35, PPE68, Rv3878, and Rv3879c amino acid sequences were prepared by multirod peptide synthesis and purchased from Chiron Mimotopes (Clayton, Australia). Peptides were used in mapping experiments at 1.5 μg/ml of each individual peptide when used in pools of 8 to 11 and at 10 μg/ml when used individually. T-cell responses to ESAT-6 were measured after in vitro stimulation with a peptide corresponding to the first 20 amino acid residues of ESAT-6 (Neosystem, Strasbourg, France), which has been identified as an immunodominant T-cell epitope on ESAT-6 in the context of H-2b (5).

Bioinformatics.

Sequence alignment was performed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) within the TubercuList database (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList). Prediction of human HLA-DR-restricted determinants was performed using the ProPred computer program (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred/) (19).

Lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays.

Spleens were harvested, and single-cell suspensions were prepared by sieving through 200-μm mesh, lysing the red blood cells, and resuspending the cells in synthetic HL-1 medium complemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. Nitrocellulose wells of an Immobilon-P plate (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) were coated with an anti-gamma interferon (anti-IFN-γ) monoclonal antibody (AN18) and incubated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% fetal calf serum. Cell suspensions were then plated at 5 × 105 cells per well with either medium alone, peptides, PPD, or ConA. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h and then extensively washed with PBS. Subsequently, biotinylated XMG1.2 monoclonal antibody was added to the wells. After a 2-h incubation and washing, the plates were incubated with avidin-alkaline phosphatase (Sigma). The presence of IFN-γ-producing cells was detected using an alkaline phosphatase substrate kit (Bio-Rad laboratory, Hercules, Calif.). Lymphoproliferative and IFN-γ responses to CFP-10 and ESAT-6 antigens were assessed as previously described (17).

Virulence studies.

SCID mice were infected intravenously via the lateral tail vein. Organs were homogenized using an MM300 apparatus (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and 2.5-mm-diameter glass beads. Serial fivefold dilutions in PBS were plated onto 7H11 agar plates with oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase and hygromycin (50 μg/ml), and the number of CFU was determined after 3 weeks of growth at 37°C.

Cellular fractionation and Western blot.

Proteins were extracted from early-log-phase cultures grown in 7H9 supplemented with albumin-dextrose-catalase and hygromycin (50 μg/ml). Cultures were concentrated by centrifugation, washed twice with 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5), and resuspended in 500 μl of the same buffer with Complete-EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Cells were then lysed by shaking on the MM300 apparatus for 10 min at maximum speed with 500 μl of acid-washed 106-μm-diameter glass beads (Sigma, St Louis, Mo.). Beads and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min. The pellet containing cell wall components was resuspended in Tris buffer, whereas the supernatant was further centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 90 min. The pellet contained membrane components while the supernatant was considered as the cytosol fraction. All cell fractions were aliquoted and stored at −20°C after protein quantification using a Bio-Rad protein assay. Supernatants from the same original cultures were concentrated using a Millipore filter with a 3-kDa cutoff (YM3). Immunoblot detections were performed as described previously (17).

RESULTS

PPE68 is the most immunogenic of the PE35, PPE68, Rv3878, and Rv3879c proteins for Th1 responses in C57BL/6 mice.

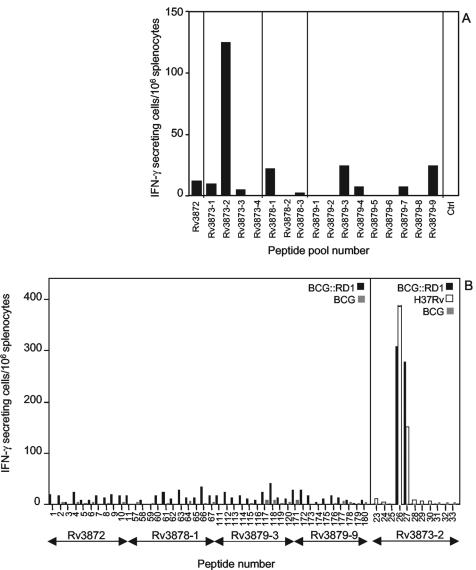

To characterize the immunogenicity of PE35, PPE68, Rv3878, and Rv3879c, C57BL/6 mice were infected by subcutaneous injection of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Three weeks later, animals were sacrificed and their splenocytes were tested for the presence of T cells secreting IFN-γ upon stimulation with pools of synthetic peptides spanning each of the four proteins (Table 1). Figure 1A shows that, with the exception of pool Rv3873-2, the peptide pools induced a modest cellular response in the infected mice. Stimulation of splenocytes with individual peptides from the five best reacting pools (Rv3872, Rv3873-2, Rv3878-1, Rv3879-3, and Rv3879-9) confirmed the low immunogenicity of Rv3872, Rv3878, and Rv3879c compared to Rv3873 in BCG::RD1-immunized mice (Fig. 1B). Moreover, two immunodominant peptides in the Rv3873-2 peptide pool were identified, Pep26 and Pep27, which induce a strong response in mice vaccinated with BCG::RD1 or infected with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, but not in BCG-vaccinated animals (Fig. 1B).

TABLE 1.

Peptides used for T-cell epitope mapping

| Protein designation | Size (amino acids) | Peptide pool no. (individual peptide no.) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rv3872 (PE35) | 99 | Rv3872 (Pep 1-11) | Member of the M. tuberculosis PE family |

| Rv3873 (PPE68) | 368 | Rv3873 1-4 (Pep 12-56) | Member of the M. tuberculosis PPE family |

| Rv3878 | 280 | Rv3878 1-3 (Pep 57-90) | Ala-rich protein |

| Rv3879c | 729 | Rv3879 1-9 (Pep 91-180) | Ala- and Pro-rich protein |

FIG. 1.

(A) Frequency of IFN-γ-secreting cells in the splenocytes of H37Rv-infected mice upon stimulation with peptide pools deriving from PE35, PPE68, Rv3878, and Rv3879c, or in the absence of peptides (Ctrl), as measured by ELISPOT assay. (B) Frequency of IFN-γ-secreting cells in the splenocytes of mice infected with BCG::RD1 or BCG after stimulation with individual peptides deriving from five peptide pools. The activity of peptides from pool Rv3873-2 was also tested on splenocytes from H37Rv-infected mice. Data are representative of three independent ELISPOT experiments.

Mapping an immunodominant epitope in PPE68.

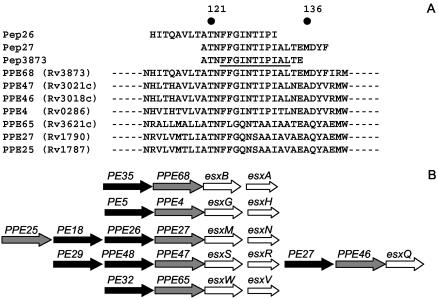

Figure 2A shows that Pep26 and Pep27 sequences overlap by 12 residues. Optimal IFN-γ responses were obtained by stimulation of splenocytes from M. tuberculosis H37Rv- and BCG::RD1-infected mice using a 16-mer peptide (Pep3873) (Fig. 2A) containing the Pep26 and Pep27 consensus sequence (not shown). Pep3873 is located in the N-terminal segment of PPE68, a highly conserved region among members of the PPE family. Interestingly, the Pep3873 sequence was predicted to contain a human HLA-DR-restricted determinant by ProPred (underlined in Fig. 2A). Sequence alignment of Pep3873 with the M. tuberculosis H37Rv proteins revealed that this predicted T-cell epitope is fully conserved in PPE47 and PPE46 and is partly conserved in PPE4, PPE65, PPE27, and PPE25 (Fig. 2A). Like PPE68, the genes for these PPE proteins are all located upstream an esx gene in esx gene clusters in the H37Rv genome (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

(A) Position of Pep26, Pep27, and Pep3873 in the PPE68 amino acid sequence. The human T-cell epitope in PPE68, as predicted by ProPred, is underlined in Pep3873. Results from sequence alignment of Pep3873 with the PPE proteins of M. tuberculosis using the BLAST program are shown. (B) Diagram comparing the genetic organization of the esx gene clusters containing PPE68, PPE47, PPE46, PPE4, PPE65, PPE27, and PPE25.

IFN-γ responses to Pep3873 are specific for PPE68.

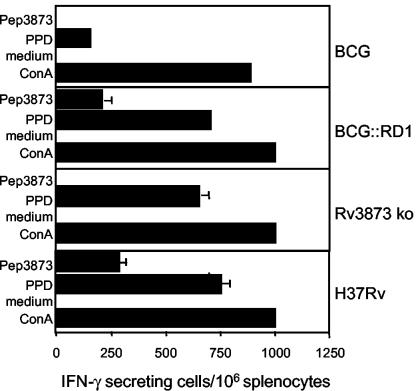

To further characterize PPE68 immunogenicity, a BCG::RD1 construct was designed where the rv3873 gene has been knocked out by insertion of an antibiotic cassette (Rv3873 ko). When mice were immunized with M. tuberculosis H37Rv or BCG::RD1, equally potent IFN-γ production against PPE68 was generated after 3 weeks, as measured by in vitro stimulation of splenocytes with Pep3873 (Fig. 3). Importantly, T cells from BCG-vaccinated mice or from mice immunized with the Rv3873 ko mutant were not stimulated by Pep3873 (Fig. 3), demonstrating that Pep3873 immunogenicity was specific for PPE68.

FIG. 3.

Frequency of Pep3873-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells in the splenocytes of mice infected with BCG::pYUB412 vector control (BCG), BCG::RD1, Rv3873 ko, or H37Rv, as measured by ELISPOT assay. Cells were prepared 3 weeks postimmunization and restimulated in vitro in presence of Pep3873. Controls include cells cultured in the absence of stimulatory agent (medium) and cells stimulated with PPD or ConA. Error bars, standard deviation.

PPE68 is localized in the membrane and the cell wall of mycobacteria.

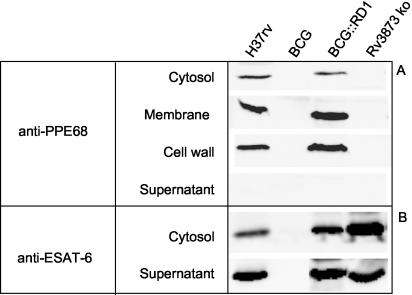

We have shown recently that PPE68 is not secreted into the supernatant of BCG::RD1 cultures (17). To further define the localization of this antigen, Western blot analysis was performed on different protein fractions of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, BCG, BCG::RD1, and Rv3873 ko cultures using a polyclonal antiserum raised against PPE68. Figure 4A shows that, as expected, PPE68 was not expressed by BCG and Rv3873 ko bacilli (Fig. 4A). In contrast, PPE68 was detected in M. tuberculosis H37Rv and BCG::RD1 cultures, predominantly in the membrane and cell wall fractions (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of the subcellular localization of PPE68 (A) and ESAT-6 (B) in M. tuberculosis H37Rv, BCG::pYUB412 vector control (BCG), BCG::RD1, and Rv3873 ko cultures.

Expression of PPE68 is not associated with virulence.

The persistence of BCG in vivo is significantly augmented by complementation with RD1 (15). Since cell wall factors are likely to interact with target cells and to play a role in mycobacterial virulence, we examined whether BCG::RD1 virulence was modified by inactivation of rv3873. When injected into severe combined immunodeficient mice (SCID), the bacterial dissemination of Rv3873 ko and BCG::RD1 were comparable in lungs and spleens (data not shown), ruling out the possibility that PPE68 is a major virulence factor in RD1.

Effect of PPE68 on CFP-10 and ESAT-6 secretion and immunogenicity.

The observation that CFP-10 and ESAT-6 secretion by recombinant BCG requires the whole RD1 gene cluster has led to the hypothesis that this genomic region encodes a secretory apparatus (17). CFP-10 and ESAT-6 expression in whole-cell lysates and secretion in culture supernatant were comparable in Rv3873 ko and BCG::RD1 (Fig. 4B), suggesting that PPE68 does not participate in the secretion of these antigens. To test whether PPE68 interferes with the immunogenicity of CFP-10 and ESAT-6, we then compared the ability of mice immunized with BCG::RD1 or Rv3873 ko to develop Th1 responses to these antigens. Comparable ESAT-6-specific lymphoproliferation was generated in mice immunized with BCG::RD1 or Rv3873 ko (Fig. 5A). Moreover, the CFP-10- and ESAT-6-specific IFN-γ responses elicited by Rv3873 ko were similar to the ones induced by BCG::RD1, whereas no cellular response to these antigens was detected in BCG-vaccinated animals (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the immunogenicity of CFP-10 and ESAT-6 appear to be independent of PPE68 expression.

FIG. 5.

(A) Lymphoproliferative response to ESAT-6 in mice infected with BCG::RD1 or Rv3873 ko, compared to BCG::pYUB412-vaccinated animals (BCG). Splenocytes were prepared 3 weeks postimmunization and stimulated in vitro with an ESAT-6 immunodominant peptide (PepESAT), an immunodominant peptide from the Ag85A mycobacterial antigen (PepAg85A), or PPD. Control cells incubated with an immunodominant peptide from an irrelevant recombinant protein (PepMalE) were included. (B) IFN-γ production, as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, by splenocytes stimulated with PepESAT, PepAg85A, and PepMalE or with recombinant ESAT-6, CFP-10, and MalE proteins. Control cells stimulated with ConA or PPD or in the absence of stimulatory agent (medium) were included. Data are representative of three independent experiments (error bars, standard deviations).

DISCUSSION

The efficacy of BCG::RD1 as a vaccine against experimental tuberculosis has been associated with the secretion of the potent T-cell antigens CFP-10 and ESAT-6 (17). However, BCG::RD1 encodes seven other potential antigens. In the present study, we have examined the immunogenicity of these RD1 products, focusing our study on PE35, PPE68, Rv3878, and Rv3879c, for which immunological reactivity in M. bovis-infected cattle has been demonstrated. Using a C57BL/6 mouse model of infection with M. tuberculosis, we showed that PE35, Rv3878, and Rv3879c do not elicit significant IFN-γ responses in vivo. This result is in agreement with the findings of Brusasca et al., who reported that PE35 and Rv3878 do not elicit delayed-type hypersensitivity in tuberculous guinea pigs and are recognized by serum antibodies only in a minor proportion of human patients with active tuberculosis (7).

The PPE68 protein was located in the membrane and cell wall fractions of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, with no evidence of secretion. An attempt to visualize PPE68 at the surface of the bacteria by immunofluorescence microscopy was not conclusive because of a strong background reactivity of the polyclonal anti-PPE68 serum on BCG control (data not shown). Background reactivity of sera from healthy human donors with the PPE68 protein has been reported previously (7) and has been attributed to cross-reactivity with mycobacterial proteins from environmental strains. Within the M. tuberculosis proteome, the strong sequence homologies between PPE proteins suggest the presence of cross-reactive motifs. This view is supported by our observation that Western blot analysis on whole-cell lysates of H37Rv using our anti-PPE68 polyclonal serum detects multiple proteins in addition to the PPE68 band (data not shown).

A T-cell epitope was mapped in PPE68, which is recognized by mice infected with M. tuberculosis H37Rv or BCG::RD1 but not by BCG-vaccinated animals or mice injected with the Rv3873 ko construct, pointing out the specificity of Pep3873 immunogenicity. Interestingly, Pep3873 was predicted by ProPred to contain a human HLA-DR-restricted determinant. Although the ProPred program was originally designed for human T-cell epitope prediction, it was useful for the identification of bovine T-cell epitopes in M. bovis antigens (19). The sequence of Pep3873 was present not only in PPE68 but also in several other PPE proteins. These proteins are present in both BCG and H37Rv (with the exception of Rv3621c) and would be expected to generate cross-reactivity with Pep3873. The absence of Pep3873 recognition in BCG-vaccinated animals therefore suggests that in BCG, the PPE proteins containing the Pep3873 sequence may either be expressed at lower levels or be less appropriately delivered to the immune system than PPE68 (Fig. 2A). Figure 2B shows that some of the corresponding genes are located similarly to rv3873, immediately upstream of an esx sequence. As mentioned earlier, these gene clusters are thought to encode protein complexes dedicated to the export of the esx products. It is tempting to speculate that the immunogenicity of PPE68 reflects the active expression of RD1 products in vivo. If this is true, we can then postulate that gene expression in the RD1 region is stronger than in the other esx operons of the genome.

Our experiments using an Rv3873 ko strain demonstrate that PPE68 expression does not modify the export of CFP-10 and ESAT-6 and plays no significant role in mycobacterial virulence in SCID mice. The function of PPE68 is therefore still undefined. In fact, rv3873 is highly likely to be nonessential for in vitro growth, as demonstrated by insertional mutagenesis in the M. tuberculosis genome (11). Our findings extend this finding to the growth of M. tuberculosis in vivo. However, the possibility remains that PPE68 is needed under particular physiological conditions.

Addendum.

After submission of this work, Okkels et al. reported the recognition of the PPE68118-135 region (corresponding to the Pep3873 sequence described in the present study) by both tuberculosis patients and BCG-vaccinated individuals (15).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the generous gift of recombinant MalE protein from Jean-Marie Clément (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) and of recombinant ESAT-6 and CFP-10 proteins from Peter Sebo and Marcella Simsova (Institute of Microbiology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic).

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust, by the European Union (contracts QLK2-CT-1999-01093 and QLK2-CT-2001-02018), by the Institut Pasteur (PTR 110, Direction de la Valorisation et des Partenaires Industriels), and by the Association Française Raoul Follereau.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Aagaard, C., M. Govaerts, L. M. Okkels, P. Andersen, and J. M. Pollock. 2003. Genomic approach to identification of Mycobacterium bovis diagnostic antigens in cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3719-3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderson, M. R., T. Bement, C. H. Day, L. Q. Zhu, D. Molesh, Y. A. W. Skeiky, R. Coler, D. M. Lewinsohn, S. G. Reed, and D. C. Dillon. 2000. Expression cloning of an immunodominant family of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens using human CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 191:551-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arend, S. M., P. Andersen, K. E. van Meijgaarden, R. L. V. Skjot, Y. W. Subronto, J. T. van Dissel, and T. H. M. Ottenhoff. 2000. Detection of active tuberculosis infection by T cell responses to early-secreted antigenic target 6-kDa protein and culture filtrate protein 10. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1850-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt, L., M. Elhay, I. Rosenkrands, E. B. Lindblad, and P. Andersen. 2000. ESAT-6 subunit vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 68:791-795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt, L., T. Oettinger, A. Holm, A. B. Andersen, and P. Andersen. 1996. Key epitopes on the ESAT-6 antigen recognized in mice during the recall of protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 157:3527-3533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosch, R., S. V. Gordon, M. Marmiesse, P. Brodin, C. Buchrieser, K. Eiglmeier, T. Garnier, C. Gutierrez, G. Hewinson, K. Kremer, L. M. Parsons, A. S. Pym, S. Samper, D. van Soolingen, and S. T. Cole. 2002. A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3684-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brusasca, P. N., R. Colangeli, K. P. Lyashchenko, X. Zhao, M. Vogelstein, J. S. Spencer, D. N. McMurray, and M. L. Gennaro. 2001. Immunological characterization of antigens encoded by the RD1 region of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome. Scand. J. Immunol. 54:448-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockle, P. J., S. V. Gordon, A. Lalvani, B. M. Buddle, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2002. Identification of novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens with potential as diagnostic reagents or subunit vaccine candidates by comparative genomics. Infect. Immun. 70:6996-7003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Conner, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, J. McLean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, J. Rogers, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 396:190-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillon, D. C., M. R. Alderson, C. H. Day, D. M. Lewinsohn, R. Coler, T. Bement, A. Campos-Neto, Y. A. W. Skeiky, I. M. Orme, A. Roberts, S. Steen, W. Dalemans, R. Badaro, and S. G. Reed. 1999. Molecular characterization and human T-cell responses to a member of a novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis mtb39 gene family. Infect. Immun. 67:2941-2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamichhane, G., M. Zignol, N. J. Blades, D. E. Geiman, A. Dougherty, J. Grosset, K. W. Broman, and W. R. Bishai. 2003. A postgenomic method for predicting essential genes at subsaturation levels of mutagenesis: application to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7213-7218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis, K. N., R. L. Liao, K. M. Guinn, M. J. Hickey, S. Smith, M. A. Behr, and D. R. Sherman. 2003. Deletion of RD1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis mimics bacille Calmette-Guerin attenuation. J. Infect. Dis. 187:117-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahairas, G. G., P. J. Sabo, M. J. Hickey, D. C. Singh, and C. K. Stover. 1996. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1274-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mustafa, A. S., P. J. Cockle, F. Shaban, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2002. Immunogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RD1 region gene products in infected cattle. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 130:37-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okkels, L. M., I. Brock, F. Follmann, E. M. Agger, S. M. Arend, T. H. M. Ottenhoff, F. Oftung, I. Rosenkrands, and P. Andersen. 2003. PPE protein (Rv3873) from DNA segment RD1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: strong recognition of both specific T-cell epitopes and epitopes conserved within the PPE family. Infect. Immun. 71:6116-6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pym, A. S., P. Brodin, R. Brosch, M. Huerre, and S. T. Cole. 2002. Loss of RD1 contributed to the attenuation of the live tuberculosis vaccines Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium microti. Mol. Microbiol. 46:709-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pym, A. S., P. Brodin, L. Majlessi, R. Brosch, C. Demangel, A. Williams, K. E. Griffiths, G. Marchal, C. Leclerc, and S. T. Cole. 2003. Recombinant BCG exporting ESAT-6 confers enhanced protection against tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 9:533-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skeiky, Y. A. W., P. J. Ovendale, S. Jen, M. R. Alderson, D. C. Dillon, S. Smith, C. B. Wilson, I. M. Orme, S. G. Reed, and A. Campos-Neto. 2000. T cell expression cloning of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene encoding a protective antigen associated with the early control infection. J. Immunol. 165:7140-7149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vordermeier, M., A. O. Whelan, and R. G. Hewinson. 2003. Recognition of mycobacterial epitopes by T cells across mammalian species and use of a program that predicts human HLA-DR binding peptides to predict bovine epitopes. Infect. Immun. 71:1980-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worku, S., and D. F. Hoft. 2003. Differential effects of control and antigen-specific T cells on intracellular mycobacterial growth. Infect. Immun. 71:1763-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]