Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the relationship between depression and functional status among a community-dwelling elderly population of 65 years and older in South Africa.

Method

Data from the first wave of the South African National Income Dynamics Study (SA-NIDS) was used, this being the first longitudinal panel survey of a nationally representative sample of households. The study focused on the data for resident adults 65 years and older (n=1,429). Depression was assessed using the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Functional status, pertaining to both difficulty and dependency in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and physical functioning and mobility (PFM), were assessed using 11 items.

Results

Functional challenges were generally higher in the older age group. There was a significant association between depression and functional dependency in ADL (adjusted OR=2.57 [CI: 1.03-6.41]), IADL (adjusted OR=2.76 [CI: 1.89-4.04]) and PFM (adjusted OR=1.66 [CI: 1.18-2.33]) but the relationship between depression and functional status, particularly PFM, appeared weaker in older age.

Conclusion

The relationship between depression symptoms and function is complex. Functional characteristics between older and younger older populations are diverse, and caution is indicated against overgeneralizing the challenges related to depression and function among this target population.

Keywords: Depression, disability, South Africa, activities of daily living, older

Introduction

Chronic illness, such as disability and depression among the aging population, is a growing public health concern in developing countries, including South Africa. There were 2.21 and 2.54 million South Africans 65 years and older in 2001 and 2011 respectively, according to Statistics South Africa (2004; 2011), resulting in the country having one of the largest elderly populations in sub-Saharan Africa (Velkoff and Kowal, 2007). Disability, particularly functional disability, is a common challenge in older people. Despite the absence of representative disability data on specific aspects of functional status as well as the challenges associated with defining disability (Iezzoni and Freedman, 2008), approximately 32-35% of South Africans 65 years and older have physical disabilities in broad terms, according to Statistics South Africa (2005). Correlating this with the absolute population growth, the number of older persons with disability and functional limitation is expected to increase in South Africa and other developing countries; while the opposite trend is noted for developed nations (Kinsella and Velkoff, 2001; Freedman et al., 2002).

While disability and depression are not an inevitable consequence of the individual ageing process, they appear to coexist with depression through reciprocal relationships (Bruce et al., 1994; Ormel et al., 2002; Lenze et al., 2001). Disability and physical illness can give rise to psychological distress, as indicated by several theoretical mechanisms (Lipowski, 1975), including impairment in the capacity to cope with needs and goals, as well as changes in body image. However, depression is also theorized to result in disability based on several mechanisms (Barry et al., 2009) including reduction in motivation and help seeking (Armenian et al., 1998) leading to poor health behavior; or by changes in neural, hormonal and immunological systems, increasing susceptibility to disease (Bruce, 2001).

Despite growing acknowledgment of the wider implications of an aging population for developing countries, nationally-representative aging studies related to depression and disability remain limited in sub-Saharan Africa. Aging in South Africa is unique in its historical legacies of poverty, violence and deprivation under the apartheid regime, as well as the current HIV/AIDS epidemic, all of which constitute significant risk factors for depression and disability among older populations. Under the apartheid government, all people with disabilities regardless of race were marginalized, but the struggle of black South Africans with disability were exacerbated by racism and deprivation which limited their access to appropriate welfare and health services (Howell et al., 2006). For decades the state pension, a critical source of livelihood in the older population, was lower for black South Africans compared with other racial/ethnic groups. Pension rate equalization only took place after 1994 (Cook and Halsall, 2012). Shouldering a high burden of HIV infection in South Africa (Abdool Karim et al., 2009), many elderly in that country live in multi-generational households (Møller, 1998) and are burdened by the epidemic, having to provide care for orphans and family members living with the disease (Schatz and Ogunmefun, 2007). In this context, the main purpose of the current study was to assess the relationship between depression and functional status among the elderly population in South Africa.

While a recent systematic review based on studies originating mostly from developed nations indicates an association between depression and physical challenges (Mezuk et al., 2012), there is little understanding as to the nature and magnitude of the relationship between depression and disability in South Africa. Given the local historical and social context of the elderly in that country, the magnitude of the relationship between depressive symptoms and disability may be pronounced. This needs to be explored in a nationally representative sample. Lastly, life expectancy is rising in South Africa (Mayosi et al., 2012), with implications for the services that need to be provided for a diverse elderly population, many of whom have specific needs. In this study, we will examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and disability, with a specific focus on how this may vary between younger and older elderly groups.

Methods

Data Source

Data (version 4 of wave 1) from the first wave of the South African National Income Dynamics Study (SA-NIDS) was used to examine functional status among adults 65 years and older in South Africa, and its relationship to depression. The SA-NIDS was the first longitudinal panel survey of a nationally representative sample of households in the country. Wave 1 of the study was conducted in 2008 by the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town, with the data first becoming publically available in 2009. It involved approximately 16,800 adults across 400 primary sampling units, with results being used from both the adult and household questionnaires. The adult questionnaire was administered to every household member aged 15 or older in the identified 7,300 houses. Using a non-randomized method, the household questionnaire was administered to the oldest woman in the household or to another household member knowledgeable about the living arrangements. The overall individual-level and household response rates were 93.3% and 69% respectively. The sampling methods are detailed in the SA-NIDS technical report (Leibbrandt et al., 2009).

Measurements

Functional status was divided into three areas: activities of daily living (ADL); instrumental activities of daily living (IADL); and physical mobility (PFM), and were assessed using 11 items. The ADL focused on self-maintenance activities that involve care of the body (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2008), and was assessed with the following four-part items: “Please indicate the level of difficulty you have with each activity ... in dressing, bathing, eating and toileting by yourself.” The IADL focused on activities to support daily life within the home and community, requiring complex interaction beyond self-maintenance activities (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2008). The IADL was assessed with the following four-part items: “Please indicate the level of difficulty you have with each activity ... in taking a bus, taxi and train by yourself, doing light work in or around the house, managing money, and cooking for yourself.” PFM was assessed with the following three-part items: “Please indicate the level of difficulty you have with each activity ... in climbing a flight of stairs, lifting and carrying heavy objects (e.g. a bag weighing 5 kg), and walking 200-300 meters.” The study participants were asked to respond to the above 11 items on a 5-point scale (1, no difficulty; 2, difficult, but can do with no help; 3, can do, only with help; 4, can't do; and 5, able to, but never do). For an item pertaining to physical ambulation, the study defined “help” to mean needing human or mechanical (crutch, cane and walker) assistance. The Cronbach's alpha values of ADL, IADL, and PFM were 0.91, 0.80 and 0.87 respectively among the 65+ age group.

Functional status in ADL, IADL and PFM was classified as two levels: ‘difficulty’ and ‘dependency’, this being consistent with other studies (Berlau et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012). These were used owing to variations in the scaling classification by level of difficulty across different national-level surveys of older people (Wiener et al., 1990; Rodgers and Miller, 1997), and also because of disagreement as to how much difficulty is required to classify a person with disability. The first variable, functional difficulty, was dichotomized based on whether the study participant experienced difficulty in ADL, IADL and PFM, with responses 2, 3 and 4 indicating the presence of difficulty, and responses 1 and 5 indicating the absence of difficulty experienced with the activity within the specific functional area.

The second variable, functional dependency, was dichotomized based on whether the study participant experienced some or no dependency in performing ADL, IADL and PFM. Here, responses 3 and 4 indicated the presence of dependency in the functional area, while responses 1, 2 and 5 indicated the absence of dependency experienced with the activity within the specific functional area. The dependency variable was intended to capture dependencies in ADL, IADL and PFM, rather than difficulty. Based on this method, ADL/IADL/PFM difficulty was defined as ‘difficulty with one or more of the three respectively’; while ADL/IADL/PFM dependency was defined as ‘needing help on one or more of the three respectively.’ These two definitions are not mutually exclusive, meaning that study participants who were characterized as having dependency would also have difficulty in functioning (but not necessarily vice versa). ‘Difficulty’ and ‘dependency’ were further used to generate the number of difficulties or dependencies for each study participant, ranging from 0 to 3 (indicating difficulties or dependencies in all ADL, IADL and PFM).

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the results of the self-reported 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) used in the adult SA-NIDS questionnaire. The CES-D, also used in other South Africa studies (Myer et al., 2008; Hamad et al., 2008), was originally designed as a 20-item tool to measure depressive symptoms in the general population (Radloff, 1977). The 10-item scale correlates well with the original version, with little loss of psychometric properties (Shrout and Yager, 1989), and is commonly used in studies among older adults (Cheng and Chan, 2005; Irwin et al., 1999; Lee and Chokkanathan, 2008). The depression score was the sum of the scores of the 10 items, and was treated as a continuum of psychological distress (Steffick, 2000), with the level of depression increasing with an increasing score. A cut-off score of 10 or more indicated the presence of depressive symptoms (Andresen et al., 1994). In our study, the Cronbach's alpha value for the CES-D was 0.78, a level of reliability consistent with another study (Cole et al., 2004).

Demographic, socio-economic and general health-related questions were used from the SA-NIDS adult and household questionnaire based on self-report including: age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, neighborhood types, perceived health status and civic participation. Perceived health status was assessed with the question “How would you describe your health at present?” To this question, responses were rated on a 5-point scale, with 1 being excellent, and 5 being poor. Civic participation was assessed based on the respondent's participation in any of 18 associations/groups. The study also controlled for frequency of household hunger within the past 12 months as a measure of financial strain.

Data Analyses

The data analysis consisted of two phases, with the first sub-analysis examining the depression symptoms and functional characteristics of the 65+ age group. This analysis was intended to find disparity in functional and depression status by different age groups. Differences in the depression symptoms and functional status were assessed using either t-test, and Pearson chi-squared statistics, adjusted using the post-stratification weight, with the second-order correction method (Rao and Scott, 1984) for survey design, and eventually converted into F statistics. Post-stratification was based on the mid-year 2008 population provided by Statistics South Africa (2008) by province and household as estimated by Wittenberg (2009).

The second sub-analysis examined the association between depression and functional status using multivariate logistic regression models. Depression was treated as the main variable of the regression in the analyses, based on an understanding that many studies have treated depression as a predictor of disability. As this study intended to examine the association between depression and disability utilizing a cross-sectional design rather than establishing temporality between the two, the use of depression as the main covariate to functional status was sufficient to achieve the study objective. Covariates in the logistic regression models included age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, neighborhood types, frequency of household hunger and civic participation. Additional analyses were performed to determine whether there is an interaction between effects of depression and age on functional status. The data were analyzed using STATA 12.

Results

Table 1 provides the results of the available demographic characteristics for the 1,429 adult resident respondents 65+ years of age (6.2%). Over half were female (62.0%) and the largest race/ethnic group was African (63.7%). Approximately 40% were widow/widower, and almost half resided in urban formal neighborhoods. The overall health, functional status (both difficulty and dependency), and depression scores are presented in Table 2. To highlight a few findings regarding functional status: the proportion of study participants with functional difficulty in ADL, IADL, and PFM was 12%, 37% and 56% respectively. When classified with respect to functional dependency, the proportions were 4%, 21% and 39%. Of the three functional areas, approximately 60% suffered no dependency, while 3% suffered from dependency in all three areas. The proportion of study participants with depression symptom (based on CES-D score ≥ 10) was approximately a third of the sample population.

Table 1.

Demographic information

| 65+ Group (n = 1,429) |

||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age: | ||

| 65-74 | 931 | 71.1 |

| 75-84 | 414 | 25.6 |

| 85+ | 84 | 3.3 |

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 479 | 38.0 |

| Female | 950 | 62.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity: | ||

| African | 1,061 | 63.7 |

| Coloured1 | 181 | 7.2 |

| Asian/Indian | 15 | 2.3 |

| White | 172 | 26.8 |

| Marital Status: | ||

| Married | 609 | 47.7 |

| Living with partner | 30 | 1.2 |

| Widow/Widower | 613 | 39.7 |

| Divorced/Separated | 52 | 4.3 |

| Never Married | 125 | 7.1 |

| Education: | ||

| Did not complete high school | 695 | 37.4 |

| Completed high school level | 613 | 46.1 |

| Beyond high school | 121 | 16.5 |

| Neighborhood Type2: | ||

| Rural Formal Area | 120 | 6.4 |

| Tribal Authority Area | 733 | 40.8 |

| Urban Formal Area | 529 | 48.4 |

| Urban Informal Area | 47 | 4.4 |

| Hunger in Household: | ||

| Never or Seldom | 1,105 | 79.5 |

| Sometimes | 259 | 16.2 |

| Often or Always | 65 | 4.3 |

| Civic Participation: | ||

| Yes | 668 | 43.0 |

All values (% and mean) are weighted.

The term ‘coloured’ is used by Statistics South Africa.

Adapted from the work of Makiwane and Kwizera (2006), rural formal area refers to predominantly commercial farms while tribal authority area refers to rural areas outside commercial farms with a mixture of traditional and civil authority. Urban formal area refers to areas close to commercial centers with physical infrastructure and formal urban planning, while urban informal area refers to informal settlements close to commercial centers with no physical infrastructure or formal urban planning.

Table 2.

Overall health, functional status and depression characteristics (n= 1,429)

| 65+ Group (n = 1,429) |

Male (n = 479) |

Female (n = 950) |

Test Value1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | F or t, p | |

| Health Status: | F (3.47, 1204) = 2.79, p = 0.03 | ||||||

| Excellent | 92 | 7.6 | 46 | 10.8 | 46 | 5.6 | |

| Very Good | 185 | 18.0 | 78 | 20.3 | 107 | 16.6 | |

| Good | 422 | 27.8 | 143 | 30.5 | 279 | 26.1 | |

| Fair | 429 | 28.0 | 128 | 22.8 | 301 | 31.2 | |

| Poor | 301 | 18.6 | 84 | 15.6 | 217 | 20.4 | |

| ADL Difficulty: | F (1, 347) = 7.90, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 178 | 11.9 | 45 | 6.8 | 133 | 15.0 | |

| IADL Difficulty: | F (1, 347) = 6.49, p = 0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 617 | 36.7 | 184 | 30.3 | 433 | 40.6 | |

| PFM Difficulty: | F (1, 347) = 34.57, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 902 | 56.4 | 241 | 44.3 | 661 | 63.7 | |

| # of Difficulties: | F (2.82, 979) = 7.77, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| 0 out of 3 | 497 | 41.4 | 219 | 51.9 | 278 | 34.9 | |

| 1 out of 3 | 335 | 23.2 | 90 | 20.2 | 245 | 25.1 | |

| 2 out of 3 | 429 | 24.5 | 130 | 22.6 | 299 | 25.7 | |

| 3 out of 3 | 168 | 10.9 | 40 | 5.3 | 128 | 14.3 | |

| ADL Dependency: | F (1, 347) = 1.05, p = 0.31 | ||||||

| Yes | 59 | 3.6 | 16 | 2.5 | 43 | 4.3 | |

| IADL Dependency: | F (1, 347) = 1.16, p = 0.28 | ||||||

| Yes | 346 | 21.4 | 109 | 19.1 | 237 | 22.8 | |

| PFM Dependency: | F (1, 347)= 21.35, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 635 | 39.3 | 155 | 28.3 | 480 | 46.1 | |

| # of Dependencies: | F (2.91, 1010) = 9.59, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| 0 out of 3 | 759 | 58.5 | 306 | 69.2 | 453 | 51.9 | |

| 1 out of 3 | 355 | 21.9 | 80 | 13.2 | 275 | 27.3 | |

| 2 out of 3 | 260 | 16.4 | 79 | 16.1 | 181 | 16.6 | |

| 3 out of 3 | 55 | 3.2 | 14 | 1.5 | 41 | 4.2 | |

| CES-D (score ≥ 10) | 562 | 33.1 | 162 | 28.1 | 400 | 36.2 | F (1, 347) = 5.24, p = 0.02 |

| CES-D (continuous) | M = 8.3 | SE = 0.20 | M = 7.8 | SE = 0.33 | M = 8.6 | SE = 0.27 | t = 2.26, p = 0.02 |

All values (% and mean) are weighted. ADL = Activity of Daily Living. IADL = Instrumental Activity of Daily Living. PFM = Physical Functioning and Mobility.

Test value for overall association with gender.

The results of the first sub-analysis related functional status and depression status across the different age groups are presented in Table 3. The proportion of persons with functional difficulty and dependency in IADL, PFM, ADL and depression symptoms was higher with increased age, with significant disparities in the first two, but not in the latter two. The study did find a higher proportion of ADL dependency (M85+ = 10.9% vs. M65-84 = 3.4%, F = 7.10, p< 0.01) in the 85+ age group compared to the 65-84 age group.

Table 3.

Functional status and depression status across age groups among 65+ age group (n=1,429)

| Age |

ADL Difficulty |

IADL Difficulty |

PFM Difficulty |

ADL Dependency |

IADL Dependency |

PFM Dependency |

CES-D1 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 65-74 | 85 | 10.2% | 339 | 33.5% | 530 | 52.6% | 28 | 2.7% | 181 | 18.6% | 358 | 35.8% | 350 | 32.2% |

| 75-84 | 73 | 15.2% | 222 | 42.2% | 304 | 63.3% | 21 | 5.3% | 122 | 25.1% | 219 | 44.9% | 176 | 33.9% |

| 85+ | 20 | 23.5% | 56 | 61.0% | 68 | 83.2% | 10 | 10.9% | 43 | 52.5% | 58 | 72.0% | 36 | 47.0% |

| F (1.85, 640.57) = 2.65, p = 0.08 | F (1.68, 584.34) = 4.45, p = 0.02 | F (1.51, 524.81) = 5.45, p = 0.01 | F (1.49, 515.78) = 2.62, p = 0.09 | F (1.83, 506.56) = 9.54, p < 0.01 | F (1.57, 433.66) = 7.01, P < 0.01 | F (1.89, 522.82) = 1.34, p = 0.26 | ||||||||

All proportions are weighted.

ADL = Activity of Daily Living

IADL = Instrumental Activity of Daily Living

PFM = Physical Functioning and Mobility

Note: Our study did find a higher proportion of ADL dependency (M85+ = 10.9% vs. M65-84 = 3.4%, F = 7.10, p< 0.01) between 85+ age group compared to the 65-84 age group.

CES-D ≥10

The results of the second sub-analysis, the regression models examining the association between depression and functional status (both difficulty and dependency), are presented in Table 4. Based on the controlled analyses, a significant association between depression (CES-D ≥ 10) and functional difficulty in ADL (adjusted OR = 3.33, t = 3.94, p< 0.01), IADL (adjusted OR = 2.25, t = 4.28, p< 0.01) and PFM (adjusted OR = 1.91, t = 3.12, p< 0.01) was found, but the significance of the results did not differ when using CES-D continuous format. Similar results between depression and functional dependency (which is at a higher threshold of functional difficulty) in ADL (adjusted OR = 2.57, t = 2.03, p= 0.04), IADL (adjusted OR = 2.76, t = 5.27, p< 0.01) and PFM (adjusted OR = 1.66, t = 2.90, p< 0.01) were found, but the significance of the results did not differ when using CES-D continuous format. The dichotomized measure of depression symptoms (CES-D ≥ 10) was not significantly related to an increase in ADL dependency; the only unadjusted model which showed no significant relations between depression and functional status. Many of the covariates, such as gender, hunger (as a measure of financial strain), education, marital status and neighborhood, were significantly related across different outcomes.

Table 4.

Association between depression and functional status multivariate logistic-regression model among 65+ age group (n=1,429)

| Outcome: | Main covariate: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 - CES-D1 |

Model 2 - CES-D1 |

Model 3 - CES-D (≥10) |

Model 4 - CES-D (≥10) |

|

| OR, t, p, (95% CI) | adjusted OR, t, p, (95% CI) | OR, t, p, (95% CI) | adjusted OR, t, p, (95% CI) | |

| ADL difficulty | 1.15, 5.39, <0.01 (1.09; 1.20) | 1.13, 4.92, <0.01 (1.08; 1.19) | 3.69, 4.15, <0.01 (1.99; 6.85) | 3.33, 3.94, <0.01 (1.83; 6.06) |

| IADL difficulty | 1.13, 6.26, <0.01 (1.09; 1.18) | 1.09, 4.14, <0.01(1.05; 1.13) | 3.27, 6.38, <0.01 (2.27; 4.71) | 2.25, 4.28, <0.01 (1.55; 3.26) |

| PFM difficulty | 1.14, 4.71, <0.01 (1.08; 1.21) | 1.09, 3.40, <0.01(1.04; 1.15) | 2.84, 4.70, <0.01 (1.84; 4.40) | 1.91, 3.12, <0.01 (1.27; 2.87) |

| ADL dependency | 1.12, 2.36, 0.02 (1.02; 1.24) | 1.14, 3.27, <0.01 (1.05; 1.23) | 2.14, 1.51, 0.13 (0.79; 5.77)* | 2.57, 2.03, 0.04 (1.03; 6.41) |

| IADL dependency | 1.12, 5.84, <0.01 (1.08; 1.16) | 1.09, 4.38, <0.01 (1.05; 1.14) | 3.47, 6.38, <0.01 (2.36; 5.09) | 2.76, 5.27, <0.01 (1.89; 4.04) |

| PFM dependency | 1.10, 4.78, <0.01 (1.06; 1.14) | 1.06, 3.01, <0.01 (1.02; 1.10) | 2.28, 4.80, <0.01 (1.63; 3.20) | 1.66, 2.90, <0.01 (1.18; 2.33) |

Total number of observation is 16,497 and the number of subpopulation (65 and older) is 1,429 with number of strata and Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) being 53 and 400, respectively for all models. All regression results are using post stratification weights. In the multivariate logistic-regression model, adjustments were made for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, neighborhood type, frequency of household hunger and civic participation. Living with partner category in the marital status was combined with married category due to small sample size.

ADL = Activity of Daily Living, IADL = Instrumental Activity of Daily Living, PFM = Physical Functioning and Mobility

CES-D in continuous form.

There is significant association (OR = 4.6, t = 3.44, p< 0.01) between severe depression symptom defined as scores >14 and ADL dependency.

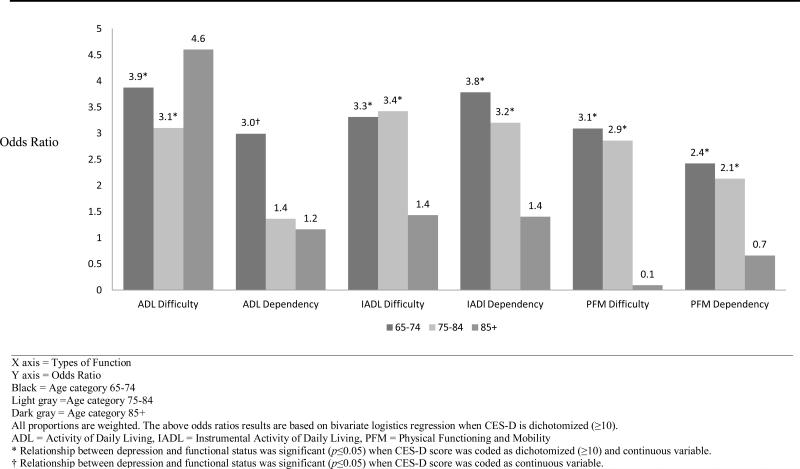

The association between depression and functional status across the different age groups is presented in Figure 1. The odds of having functional difficulty/dependency appeared several times higher for participants with depressive symptoms among the younger old (64-74) group. However, the odds of having functional difficulty/dependency appeared nearly the same between study participants with or without depressive symptoms among the older old (85+) group. We found a significant interaction between effects of depression and age (adjusted OR= 0.94, t = -2.09, p= 0.04) on PFM difficulty, but not in other functional outcomes.

Figure 1.

Relationship between Depression Symptoms and Functional Status by Age Category

Discussion

The study found that depression was significantly associated with functional challenges in ADL, IADL and PFM after adjusting for demographic factors and socioeconomic conditions among older people in South Africa. This is consistent with similar studies that examined the association between depression and functional outcome (Beekman et al., 2002), including ADL (Mehta et al., 2002; Barry et al., 2009), IADL (Han and Jylha, 2006; Kiosses and Alexopoulos, 2005) and PFM (Mossey et al., 2000; Callahan et al., 1998: Penninx et al., 1999). However, as found in another study (Gurland et al., 1988), the relationship between depression and functional difficulty/dependency is often weaker with higher age, particularly in PFM. Disparity in functional status in ADL, IADL and PFM across different age groups was also found, this being similar to other studies in developed and developing nations (Berlau et al., 2009; Andersen-Ranberg et al., 1999; Hairi et al., 2010). No significant association between the advanced age group and depressive symptoms was detected, a finding similar to another study using CES-D (Blazer et al., 1991).

The relationship between depression symptom and functional status is often complex, and there may be several plausible explanations for a weakened association between depression and functional challenges with age progression. Changes in coping strategies to overcome challenges (McCrae and Costa, 1986), and the onset of new physical illness are strong correlates with depression (Kukull et al, 1986) and may explain these findings. However, it is also likely that selection bias may have resulted from people with severe characteristics moving from the community to an institutional environment (Gurland et al., 1988). It may also relate to the smaller sample size in the 85+ age group (Table 1). Adding to such complexity, a dichotomized measure of depression symptom (CES-D ≥ 10) was not found to be significantly related to an increase in ADL dependency as described in Table 4, but the result needs to be interpreted with some caution. The study by Barry and colleagues (2009) found that only high depressive symptoms were associated with severe disability in ADL. Utilizing a cut-off score greater than 14 to categorize severe depressive symtoms consistent with other studies (Kilbourne et al., 2002; Swenson et al., 2008), resulted in high depressive symptoms being significantly associated with dependence in ADL (OR = 4.6, t = 3.44, p< 0.01). This speaks to the importance of incorporating different levels of functional status (difficulty and dependency) and severity of depressive symptoms (none, mild, and severe) across different types of functional assessment (ADL, IADL and PFM).

Approximately 60% of the participants reported at least one type of functional difficulty, with about 40% reporting at least one functional dependency, and more than half having some form of physical functioning and mobility difficulty. Approximately one third had depressive symptoms which is similar to other South African studies (Ardington and Case, 2009), but exceeds the prevalence estimate of depressive symptoms (31.2%) among HIV positive person in sub-Saharan Africa based on a recent systematic review (Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., 2012). While differences in measurement make cross-national comparison difficult, the association between depression symptoms and certain types of functioning appeared more pronounced in this study than in community-based studies conducted in developed nations, including the United States (Penninx et al., 1999) and Italy (Dalle Carbonare et al., 2009). This indicates the importance of addressing mental health and other chronic health issues in conjunction with infectious disease challenges.

The limitations included: firstly, the cross-sectional nature could have resulted in selection bias. Reciprocal and temporal relationships between functional status and depression in late life could therefore not be established; this being a key aspect in determining the optimal time for interventions. Further studies utilizing a longitudinal study design are warranted. Secondly, strong measures of cognitive impairment, or data relating to the diagnosis of depressive disorder, were not available.

Late-life depression is often under-treated or undetected (Klap et al., 2003), due possibly to patient denial and stigma related to depression (Evans and Mottram, 2000), patient belief that depression is a normal part of aging (Sarkisian et al., 2003), as well as bias by health providers towards older patients to accept more symptoms and lower functioning (Alexopoulous, 1992). Untreated late-life depression is not only associated with lower functioning but also impacts on lower quality of life and poor adherence to treatment (Katon, 2003). Within a context where negative community attitudes and poor knowledge about mental illness exist (Gureje et al., 2005; Gureje and Lasebikan, 2006), raising awareness among older patients about late-life depression is crucial. Older adults with disability and depressive symptoms often do not consistently mobilize informal care in the long-term (Lin and Wu, 2011), and acquiring social support often becomes more challenging at an older age (Barnes et al., 2004). Therefore, formal services may be the last resort for this vulnerable population; little time however is spent discussing mental health issues between the primary care physician and the elderly patient, even when the latter faces depression (Tai-Seale et al., 2007).

Our study highlights the need for a better understanding of the different characteristics and challenges of the younger and older elderly population. The relationship between depression and functional status weakened with age, particularly in PFM. Given that the relationship between depression and functional status may be more pronounced in the younger elderly population, early intervention may be warranted. This study calls for closer attention to mental health conditions in older patients; improvement of early detection of depression; and provision of appropriate treatment for depressive symptoms in elderly patients in primary care settings. The last should be based on shared responsibility between the patients and healthcare providers to reverse excess disability.

Conclusion

By investigating the coexistence of depression symptoms and functional status, this study advances knowledge about the important relationship between depression and functional status within a sub-Saharan country; and is intended to identify future interventions with which to target community-dwelling older adults in South Africa. While there was an overall association between depression and functional status among the elderly, there was a disparity in functional status and its relationship with depressive symptoms across the different elderly age groups. In summary, the findings raise caution about over-generalizing an association between depression and functional status, given the characteristics and dissimilar challenges between younger and older elderly groups.

Key points.

There is a disparity in the functional status across different age groups, which suggests caution against overgeneralization in this target population due to characteristics and challenges between older and younger elderly population.

There is an overall association between depression and functional status in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activity of daily living (IADL), and physical functioning and mobility (PFM) among older adults in South Africa, a developing country.

However, we detected a weakening of the relationship of depression and functional status, particularly PFM, in older age.

Acknowledgments

The baseline study of South African National Income Dynamics Study (SA-NIDS) was conducted by the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU) based at the University of Cape Town's School of Economics. The research team is led by Murray Leibbrandt (SALDRU director/University of Cape Town) and Ingrid Woolard (SALDRU's chief research officer). The data was accessed through Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit. National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) 2008, Wave 1 [dataset]. Version 4. Cape Town: Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit [producer], 2012. Cape Town: DataFirst [distributor], 2012.

Dr. Tomita was supported by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director, Fogarty International Center, Office of AIDS Research, National Cancer Center, National Eye Institute, National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute, National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research, National Institute On Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Health, and NIH Office of Women's Health and Research through the International Clinical Research Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- Abdool Karim S, Churchyard GJ, Abdool Karim Q, et al. HIV infection and tuberculosis in South Africa: an urgent need to escalate the public health response. Lancet. 2009;374:921–933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60916-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulous GS. Geriatric depression reaches maturity. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1992;7:305–306. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen-Ranberg K, Christensen K, Jeune B, et al. Declining physical abilities with age: a cross-sectional study of older twins and centenarians in Denmark. Age and Ageing. 1999;28:373–377. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardington C, Case A. Health: Analysis of the NIDS Wave 1 Dataset. University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2009. Available at: http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/home/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=97&Itemid=19. [Google Scholar]

- Armenian HK, Pratt LA, Gallo J, et al. Psychopathology as a predictor of disability: A population-based follow-up study in Baltimore, Maryland. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;148:269–275. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008;62:625–683. doi: 10.5014/ajot.62.6.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, et al. A longitudinal study of black–white differences in social resources. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:S146–S153. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.s146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry LC, Allore HG, Bruce ML, et al. Longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and disability burden among older persons. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2009;64:1325–1332. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman ATF, Penninx BWJH, Deeg DJH, et al. The impact of depression on the well-being, disability and use of services in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105:20–27. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.10078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlau DJ, Corrada MM, Kawas C. The prevalence of disability in the oldest-old is high and continues to increase with age: findings from The 90+ Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;24:1217–1225. doi: 10.1002/gps.2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, et al. The association of age and depression among the elderly: An epidemiologic exploration. Journal of Gerontology. 1991;46:M210–M215. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.6.m210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, et al. The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1796–1799. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML. Depression and disability in late life: Directions for future research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9:102–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Wolinsky FD, Stump TE, et al. Mortality, symptoms, and functional impairment in late-life depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13:746–752. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ST, Chan ACM. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in older Chinese: thresholds for long and short forms. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20:465–470. doi: 10.1002/gps.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JC, Rabin AS, Smith TL, et al. Development and validation of a Rasch-derived CES-D Short Form. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:360–372. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook I, Halsall J. Aging in comparative perspective: processes and policies. Springer; New York: 2012. Aging in South Africa. pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dalle Carbonare L, Maggi S, Noale M, et al. Physical disability and depressive symptomatology in an elderly population: A complex relationship. The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA). American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17:144–154. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e31818af817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M, Mottram P. Diagnosis of depression in elderly patients. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2000;6:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Martin LG, Schoeni RF. Recent trends in disability and functioning among older adults in the United States: Asystematic Review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:3137–3146. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.24.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Ephraim-Oluwanuga O, et al. Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:436–441. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Lasebikan V. Use of mental health services in a developing country. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:44–49. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurland BJ, Wilder DE, Berkman C. Depression and disability in the elderly: Reciprocal relations and changes with age. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1988;3:163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Hairi N, Bulgiba A, Cumming R, et al. Prevalence and correlates of physical disability and functional limitation among community dwelling older people in rural Malaysia, a middle income country. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:492. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad R, Fernald LCH, Karlan DS, et al. Social and economic correlates of depressive symptoms and perceived stress in South African adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2008;62:538–544. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Jylha M. Improvement in depressive symptoms and changes in self-rated health among community-dwelling disabled older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2006;10:599–605. doi: 10.1080/13607860600641077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell C, Chalklen S, Alberts T. A history of the disability rights movement in South Africa. In: Watermeyer B, Swartz L, Lorenzo T, et al., editors. Disability and social change: A South African agenda. Human Sciences Research Council Press; Cape Town: 2006. pp. 46–84. [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni Li, Freedman VA. Turning the disability tide: The importance of definitions. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299:332–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: Criterion validity of the 10-Item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Justice AC, Rollman BL, et al. Clinical importance of HIV and depressive symptoms among veterans with HIV infection. Journal General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:512–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiosses DN, Alexopoulos GS. IADL functions, cognitive deficits, and severity of depression: a preliminary study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:244–249. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella K, Velkoff VA. An aging world: 2001. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington D.C.: 2001. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/p95-01-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Klap R, Unroe KT, Unutzer J. Caring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11:517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukull WA, Koepsell TD, Inui TS, et al. Depression and physical illness among elderly general medical clinic patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1986;10:153–162. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AEY, Chokkanathan S. Factor structure of the 10-item CES-D scale among community dwelling older adults in Singapore. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23:592–597. doi: 10.1002/gps.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibbrandt M, Woolard I, de Villiers L. Methodology: Report on NIDS Wave 1. University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2009. Available at: http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/home /index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=105&Itemid=19. [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM, et al. The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9:113–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liebel DV, Friedman B. An investigation into which individual instrumental activities of daily living are affected by a home visiting nurse intervention. Age and Ageing. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs151. DOI: 10.1093/ageing/afs151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin IF, Wu HS. Does informal care attenuate the cycle of ADL/IADL disability and depressive symptoms in late life? Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2011;66:585–594. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipowski ZJ. Psychiatry of somatic diseases: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, classification. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1975;16:105–124. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(75)90056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makiwane M, Kwizera S. An investigation of quality of life of the elderly in South Africa, with specific reference to Mpumalanga province. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2006;1:297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Mayosi BM, Lawn JE, van Niekerk A, et al. Health in South Africa: changes and challenges since 2009. Lancet. 2012;380:2029–2043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality, coping, and coping effectiveness in an adult sample. Journal of Personality. 1986;54:385–404. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE. Cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and functional decline in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:1045–1050. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezuk B, Edwards L, Lohman M, et al. Depression and frailty in later life: a synthetic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;27:879–892. doi: 10.1002/gps.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller V. Innovations to promote an intergenerational society for South Africa to promote the well-being of the black African elderly. Society in Transition. 1998;29:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mossey JM, Gallagher RM, Tirumalasetti F. The Effects of pain and depression on physical functioning in elderly residents of a continuing care retirement community. Pain Medicine. 2000;1:340–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Smit J, Roux LL, et al. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2008;22:147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Bass J, Alexandre P, et al. Depression, alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:2101–2118. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Rijsdijk FV, Sullivan M, et al. Temporal and reciprocal relationship between IADL/ADL disability and depressive symptoms in late life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:P338–P347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.p338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, et al. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rao JNK, Scott AJ. On Chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. The Annals of Statistics. 1984;12:46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers W, Miller B. A comparative analysis of ADL questions in surveys of older people. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52B:21–36. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CA, Lee-Henderson MH, Mangione CM. Do depressed older adults who attribute depression to “old age” believe it is important to seek care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:1001–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E, Ogunmefun C. Caring and contributing: The role of older women in rural South African multi-generational households in the HIV/AIDS era. World Development. 2007;35:1390–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Yager TJ. Reliability and validity of screening scales: Effect of reducing scale length. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1989;42:69–78. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa . Census 2001: Primary tables South Africa Census ’96 and 2001 compared. Statistics South Africa; Pretoria: 2004. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/census01/html/RSAPrimary.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa . Census 2001: Prevalence of disability in South Africa. Statistics South Africa; Pretoria: 2005. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/census01/html/disability.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa . Mid-year population estimates 2008. Statistics South Africa; Pretoria: 2008. Available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/p0302/p03022008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa . Mid-year population estimates 2011. Statistics South Africa; Pretoria: 2011. Available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Steffick DE. Documentation of affective functioning measures in the health and retirement study. University of Michigan Survey Research Center; Ann Arbor: 2000. Available at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/dr-005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson SL, Rose M, Vittinghoff E, et al. The influence of depressive symptoms on clinician-patient communication among patients with type 2 diabetes. Medical Care. 2008;46:257–265. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31816080e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire T, Colenda C, et al. Two-minute mental health care for elderly patients: Inside primary care visits. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:1903–1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velkoff VA, Kowal PR. Population aging in sub-Saharan Africa: demographic dimensions 2006. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington D.C.: 2007. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/p95-07-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener JM, Hanley RJ, Clark R, et al. Measuring the activities of daily Living: Comparisons across national surveys. Journal of Gerontology. 1990;45:S229–S237. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.s229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg M. Weights: Report on NIDS wave 1. University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2009. Available at: http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/home/index.php?/Nids-Documentation/technical-papers.html. [Google Scholar]