Abstract

Background

This study evaluated the use of a modified Delphi technique in combination with a previously developed alcohol advertising rating procedure to detect content violations in the US Beer Institute code. A related aim was to estimate the minimum number of raters needed to obtain reliable evaluations of code violations in television commercials.

Methods

Six alcohol ads selected for their likelihood of having code violations were rated by community and expert participants (N=286). Quantitative rating scales were used to measure the content of alcohol advertisements based on alcohol industry self-regulatory guidelines. The community group participants represented vulnerability characteristics that industry codes were designed to protect (e.g., age < 21); experts represented various health-related professions, including public health, human development, alcohol research and mental health. Alcohol ads were rated on two occasions separated by one month. After completing Time 1 ratings, participants were randomized to receive feedback from one group or the other.

Results

Findings indicate that (1) ratings at Time 2 had generally reduced variance, suggesting greater consensus after feedback, (2) feedback from the expert group was more influential than that of the community group in developing group consensus, (3) the expert group found significantly fewer violations than the community group, (4) experts representing different professional backgrounds did not differ among themselves in the number of violations identified; (5) a rating panel composed of at least 15 raters is sufficient to obtain reliable estimates of code violations.

Conclusions

The Delphi Technique facilitates consensus development around code violations in alcohol ad content and may enhance the ability of regulatory agencies to monitor the content of alcoholic beverage advertising when combined with psychometric-based rating procedures.

Keywords: alcohol, advertising, adolescents, alcohol industry, self-regulation

Introduction

There is general agreement that alcohol advertising should not be directed at vulnerable groups such as children and young adults, nor should it portray a variety of objectionable content. To promote the responsible advertising of alcoholic beverages, industry groups have developed self-regulation guidelines describing which types of content (and exposure markets) are unacceptable. An example of an industry self-regulation guideline is the following statement from the 2006 US Beer Institute Advertising and Marketing Code (Beer Code): Beer advertising and marketing materials should not portray, encourage or condone: drunk driving; situations where beer is being consumed rapidly, excessively, involuntarily, as part of a drinking game, or as a result of a dare; persons lacking control over their behaviour, movement or, speech in any way suggest that such conduct is acceptable. Despite the widespread adoption of self-regulatory guidelines by the alcohol industry, there exists no reliable, quantitative and systematic means to determine whether marketing practices conform to these industry self-regulation codes, other than qualitative procedures employed by industry appointed complaint review groups. Moreover, there is little agreement about how they should be enforced. In the face of criticism from the U.S. government and public interest groups (Anderson, 2007; Bonnie and O’Connell, 2004; Evans and Kelly, 1999), the alcohol industry has established its own monitoring capabilities. But industry dominance of the review process may constitute a conflict of interest and has been criticized for its lack of objectivity and responsiveness to complaints about guideline violations (Anderson, 2007; Jones and Donovan, 2002).

To address these concerns, we developed a set of rating procedures that can be used by public health professionals and government officials to monitor the content of alcohol advertising on television and in other media (Babor et al., 2008; 2010). The rating scale items were designed to measure the content guidelines of the U.S. Beer Code as well as codes developed by the US Wine Institute and the Distilled Spirits Council. A test-retest reliability study was conducted with 74 participants who rated five alcohol advertisements on two occasions separated by one week (Babor et al., 2008). The results showed that naïve (untrained) raters can provide consistent (reliable) ratings of the main content guidelines proposed in the U.S. Beer Code.

The main purpose of the present study was to further validate the rating procedure by incorporating a modified Delphi technique as an enhanced method to evaluate advertising code violations. The Delphi technique consists of a series of sequential questionnaires or ‘rounds’, interspersed by controlled feedback with the intent of obtaining a reliable consensus of opinion from a group of experts or important constituency groups. Consensus methods like the Delphi technique have been used to enhance group decision-making, develop public policies and estimate unknown parameters by synthesizing expert opinion in areas where there is uncertainty, controversy or incomplete evidence. The technique is based on the idea that accurate and reliable assessment can be best achieved by consulting a panel of “experts” and subsequently accepting the group consensus as the best estimate of the answer (Dalkey and Helmer, 1963; Hasson et al., 2000; Powell, 2002). The rationale for using the Delphi technique is its feasibility and economy. The Delphi has been described as a quick (Everett, 1993), cheap (Jones et al. 1992) and efficient way to access the knowledge and abilities of a group of experts. Another advantage of the Delphi technique for evaluating self-regulation codes is that it gives raters two opportunities to view an ad, as well as feedback from important reference groups.

The present study compared ad ratings obtained from a “community group” and an “expert group” at Time 1 (initial rating) and Time 2 (feedback-assisted rating). We hypothesized that the variance among raters would be reduced at the time of a second rating after receiving feedback about the group average, thereby demonstrating greater consensus. To the extent that young adult “message receivers” may perceive the content of alcohol advertising differently than older health professionals (Austin et al., 2007; Graber, 1989), it was also expected that the expert raters would perceive a higher number of code violations than community raters, because the former would be more likely to approach the rating task from a public health perspective. Similarly, we expected that within the expert sample, raters with specialization in alcoholism, mental health and public health would find more violations than communications specialists or business faculty.

The second aim of the study was to evaluate the effect of group feedback on the variance in item ratings reported by each group. We therefore varied the feedback provided to each group, such that half of the experts received feedback from the community group, and vice versa. The rationale for studying the effects of mixed feedback is based on research showing that expert panels are influenced by the types of feedback they receive (Coulter et al., 1995; Leape et al., 1992). We hypothesized that feedback from the expert group would have a greater influence on the community group’s second session ratings than vice-versa because of the latter group’s greater prestige and experience.

The third aim of the study was to estimate the minimum number of raters necessary to produce reliable content ratings, in order to inform the process of vetting alcohol advertisements for possible code violations.

Method

Research Design

The study employed a two group repeated measures cross-over design that compared the guideline ratings of a “community group” and an “expert group” at Time 1 (initial rating) and Time 2 (feedback-assisted rating). The community group consisted of 147 research volunteers selected to represent the vulnerability characteristics the industry codes were designed to protect (e.g., underage drinkers, college students). The expert group consisted of 139 research volunteers selected on the basis of their expertise in four areas (e.g., public health, mental health, alcohol research, and marketing/ business) considered to be highly relevant to the evaluation of industry advertising guidelines from a public health perspective. Following completion of the first round of ratings, participants were randomized to receive feedback either from their own group or from the other group. We used an urn randomization procedure (Stout et al., 1994) designed to balance across key individual variables (e.g., age, gender) considered likely to affect outcomes. Randomization occurred after the first round ratings were completed.

Research Participants

The community group was defined as individuals who need to be protected from alcohol advertising because they are considered particularly vulnerable to the detrimental effects of alcoholic beverages. Based on the various industry codes and literature published by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Institute of Medicine, alcohol policy experts and industry social aspect organizations (Bonnie and O’Connell, 2004; ICAP, 2001; Proctor et al., 2005), both the content and the exposure guidelines are designed to protect vulnerable groups defined by age, gender, ethnic group status and other characteristics. Therefore the following were considered vulnerable: college students; young adults, especially drinkers below the age of 21; evidence of engaging in risky drinking; women of childbearing age because of unintended pregnancy risk; and ethnic minority status.

Community participants were recruited in approximately equal proportions from the campuses of the University of Connecticut (Storrs) and Manchester Community College by posters, classroom announcements and other solicitations. Recruitment was designed to maximize the number of participants who had one or more of the vulnerability factors.

Expert group participants were chosen to reflect the kinds of expertise required to protect the health of vulnerable populations likely to be adversely affected by inappropriate advertising. The following experts were recruited: 1) Mental health professionals: psychiatrists, psychologists, interns, clinical residents, and graduate students ( n= 25); 2) Faculty and other professionals trained in marketing, advertising, communications science and business (n=30); 3) Health and Human Development professionals specializing in adolescent development, physical health, and population health, including educators, school psychologists, physical and occupational therapists, and public health professionals (n= 29); and 4) Alcohol research professionals, including post doctoral fellows (n= 55).

The expert group was selected on the basis of criteria recommended for Delphi participants, i.e., credibility, impartiality, integrity, independence and specialized expertise (Hasson, et al., 2000; Powell, 2003). Graduate students, residents, interns and postdoctoral research fellows were also included to provide a range of participant ages and to benefit from the fact that professionals in training are likely to be very familiar with ethical issues. Participants were recruited through the list-serves of professional organizations, such as the Research Society on Alcoholism and the Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug section of the American Public Health Association, and through email solicitations to faculty and graduate student organizations.

In all, 149 experts participated in session 1, and 93% (N=139) continued with session 2. Session 1 was completed by 161 participants from the community group and 91% (N=147) of these participants subsequently completed session 2. Of 139 experts, 93 (67%) were female; of the 147 community participants, 67 (46%) were female. The mean age for the expert group was 41 years (sd=13); the mean age of the community sample was 21 years (sd=4). The expert group had on average 20 (sd=3) years of education, whereas the average education level among the community group was 14 years (sd=1.7). The mean AUDIT score (Babor et al., 2001) for the expert group was 5 (sd=3), whereas the mean AUDIT score for the community group was 8 (sd=6). Regarding the vulnerability characteristics of the community group, all gave evidence of having one or more of the vulnerability characteristics considered important for an evaluation of alcohol ad content: 99% were college students; 57% were under age 21, 36% of the males and 29% of the females scored above the AUDIT cut-off score for risky drinking; 99% of the women were of child bearing age (18–40); and 35% self-identified as members of ethnic minority groups.

Advertisements

We selected six television ads that had national exposure in markets likely to contain significant proportions of young adult and underage viewers. The ads represented situations and characters likely to contain a variety of code violations in order to evaluate the performance of the rating scales with the two groups of raters. To reduce the time burden on participants, we limited the ads to beer and malt liquor products that could be evaluated by 23 items measuring developed by Babor et al. (2008) to measure the content guidelines of the US Beer Code (2006). The content themes of the six advertisements can be described as follows: 1) Noise Complaint. A policeman investigates a noise complaint at a party where young adults are drinking Samuel Adams Light beer. 2) Laundromat party. Two young men doing laundry and drinking Smirnoff Ice flirt with three young women. 3) Brian's friends talk. A group of young men drinking Miller Lite Beer talk with their housemate Brian. 4) Man hides beer. A man riding in an elevator describes his effort to boost morale by hiding Bud Light beer around the office. 5) Two peep holes. A woman hosting a party uses two peep holes (upper and lower) to look over party guests and their alcoholic beverages before admitting them. 6) Ted Ferguson Daredevil. Ted Ferguson goes shopping with his girlfriend instead of watching the football playoffs with friends.

Procedures

The alcohol ads were rated using a web-based program that included an introduction to the study, a rating tutorial and six ad rating modules. After providing informed consent participants completed a short questionnaire measuring demographic characteristics and drinking behaviours. Next, the tutorial explained the purpose of industry codes and public health concerns related to alcohol advertisements. The tutorial then showed an illustrative ad to demonstrate comprehension of the task and competence in recording their answers.

After completing the tutorial, the web-program presented the first ad accompanied by a still image of a key character from the ad. The respondents then completed a series of rating questions. This sequence was repeated for each of the six commercials. To prevent order effects, the sequence of ads was randomized.

Participants began the second rating session (Time 2) approximately one month after the first round. The interval between sessions was determined primarily by logistics, i.e., how long it took to conduct the first round with a representative group of participants, summarize their data, and provide individualized feedback for the second round. The Time 2 web program included the participant’s Time 1 ratings along with a brief description of the group whose feedback was provided. This feedback was presented visually in terms of the reference group’s average item ratings. Participant’s Time 2 responses were thus informed by information about their own Time 1 ratings and those of the reference group.

The first session lasted approximately 90 minutes; the second approximately one hour. Participants were compensated for their time with up to $100 in American Express® gift cheques. Study procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Protection Office at the University of Connecticut Health Center.

Measures

Using procedures developed by Babor et al. (2008), the eight content guidelines of the U.S. Beer Code were operationally defined by means of 23 items that used four types of measurement scales. Likert scales were used to measure the viewers’ agreement or disagreement with statements of fact and opinion (e.g. “This ad depicts the image of Santa Claus” or “This ad depicts situations where beer is being consumed excessively”). These items were rated using the following response categories: Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neither Disagree nor Agree, Agree, Strongly Agree. A second type of measurement utilized age perception items, designed to measure the viewer’s perception of the actor’s age (e.g. “How old do you think this actor is?”). We also measured the viewer’s perception of the age group to which the ad primarily appealed (e.g. “The images in this ad are most appealing to which of the following age groups: below 21; between 21 and 30; between 31 and 40; between 41 and 50; above 50”). A third measurement was designed to assess the viewer's perception of the appeal of the ad (e.g. “How appealing are the images in the ad to you?”). A 5-point Likert scale provided response choices ranging from “Very Unappealing” to Very appealing”. The fourth type of measurement consisted of items related to the viewer’s perception of the amount of drinking taking place (e.g. “How many drinks do you estimate this person is likely to consume in the situation shown in the ad?”). The viewers responded with estimates of the number of standard drinks consumed by the character depicted in the ad.

Violations were scored using procedures developed by Babor et al. (2008). For example, if the rater agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “This ad depicts situations where beer is being consumed excessively,” this was scored as a violation of guideline 2 of the Beer Code. Similarly, if the estimated age of the actor was 20 or younger, this was scored as a violation of guideline 3. An overall violation score was obtained by summing the number of individual guidelines where one or more items indicated a violation.

Data Analyses

We examined whether there was greater consensus after the second rating by using a measure of the reduction of variance in the rating scales, i.e., the F statistic, which tests the ratio between the variances observed between two time points. We used the Pearson Chi-square test to evaluate whether the number of rating items with significantly decreased variance was more likely to occur in certain categories defined by group status and feedback status in a 2 × 2 contingency table.

To examine whether expert raters would perceive more code violations than members of the community group, it was first necessary to control for differences in sample characteristics that are relevant to the evaluation of the industry codes. The expert and community group samples differed in terms of age (t=18.04, 284 df, p <.01), gender (χ12=13.2, p<.01), years of education (t=20.1, 284 df, p<.01) and AUDIT scores (t=5.3, 284 df, p<.01). These factors were therefore included in the fitted model as covariates. The main analysis consisted of a regression approach, with participant group status and time as the two main effects of interest. We examined the effect of the group-by-time interaction to ascertain whether there was a differential time effect by group status. We also examined subgroup differences across the different professional groups comprising the expert sample. The outcome variables in the adjusted models include aggregate number of violations across the six ads as well as guideline-specific aggregate violations across the six ads.

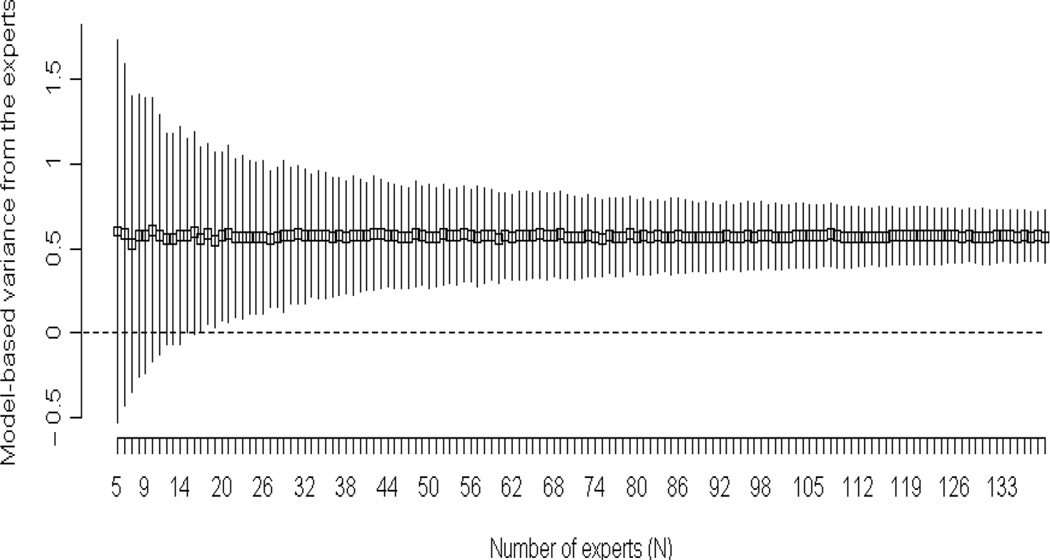

We employed a variance components model to assess the most efficient size of the expert rater group. A bootstrap method was used to examine both the mean number of perceived content violations and the variance from the raters as a function of the number of raters. To examine the changes in the mean number of violations and the model-based variance from the experts, we randomly selected groups of 5 raters with replacement and calculated the mean and the variance attributable to the raters (Step 1). To capture central tendency, we repeated random group selection for 500 simulations and reported the means of these 500 simulations based on N=5 (Step 2). We repeated steps 1 and 2 by increasing the number of raters from 5 to the total number of raters. We plotted both the mean number of violations and the model-based variance attributable to the experts against the number of the raters. We further examined the 95% confidence levels (θ̂ ± 1.96 * boots trapped SE) for the simulated means to ascertain the minimal number of raters required to achieve stable estimates of code violations in a series of alcohol advertisements.

Results

Table 1 shows the number of rating items that exhibited decreased variance from Time 1 to Time 2. Out of a total of 23 rating items, decreased variance was common, ranging from 19 items to 23 items across the six different ads and four feedback groups. Counting the number of items that showed a significant decrease of variance, we observed the fewest reductions among Group 1 (the expert group receiving feedback from community participants), where the number of significant items across the six ads was between 1 and 2; whereas the ranges for the other three viewer groups across the six ads were between 8 and 18. The numbers of items that showed decreased variance as well as significantly decreased variance are presented in the last column of the table. A comparison of the total number of items that showed significantly reduced variance was statistically significant (Pearson Chi-square =26.1, df=1, p<.01). Viewers from the community group had the largest number of significant variance reductions (85 for those receiving feedback from the experts and 74 for those receiving feedback from their own group). The smallest number of significant variance reductions was observed for the experts receiving feedback from the community group (only 9).

Table 1.

Number of rating items (out of 23) showing decreased variance from Time 1 to Time 2 and the number of items that reached statistical significance for decreased variance

| Feedback Group | Number of rating items showing decreased variance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad 1 | Ad 2 | Ad 3 | Ad 4 | Ad 5 | Ad 6 | Total | ||

| Group 1. Experts receiving community participants’ feedback (n=71) | Decreased variance | 19 | 21 | 23 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 128 |

| p-value<.05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 9 | |

| Group 2. Experts receiving experts’ feedback (n=68) | Decreased variance | 23 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 135 |

| p-value<.05 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 10 | 68 | |

| Group 3. Community participants receiving experts’ feedback (n=75) | Decreased variance | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 20 | 22 | 133 |

| p-value<.05 | 13 | 16 | 8 | 17 | 13 | 18 | 85 | |

| Group 4. Community participants receiving community participants’ feedback (n=72) | Decreased variance | 22 | 23 | 22 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 129 |

| p-value<.05 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 74 | |

Table 2 describes viewers’ perceptions of code violations (summed across the six ads) according to time, group, and feedback category. Controlling for age (β=0.12, p<.01), sex (β=−0.65 for male, p=.20), years of education (β=−0.11, p=.33) and AUDIT score (β=0.10, p=.08), expert viewers identified fewer violations (β=−2.78, p<.01) as compared to the community participants at Time 1 and Time 2. Table 2 also shows that the model-adjusted means of identified violations across six ads decreased in both groups from the first session to the second session. Contrary to our hypothesis, the model-adjusted mean number of violations identified by the community group was significantly higher in both sessions (20.5 and 19.8).

Table 2.

Adjusted number of Beer Code guideline violations by group status, feedback status and cross-over status

|

Number of violations |

||

|---|---|---|

| By group status | Time 1 | Time 2 |

| Expert participants | 17.8 | 17.0 |

| Community participants | 20.5 | 19.8 |

| By feedback status | Time 1 | Time 2 |

| Expert feedback | 19.2 | 18.5 |

| Community feedback | 19.1 | 18.4 |

| By 2*2 cross-over status | Time 1 | Time 2 |

| Group 1: Experts receiving community feedback | 17.7 | 16.9 |

| Group 2: Experts receiving experts’ feedback | 17.8 | 17.0 |

| Group 3: Community participants receiving experts’ feedback | 20.6 | 19.8 |

| Group 4: Community participants receiving community feedback | 20.5 | 19.7 |

Note: The adjusted means are based on the following fitted model: # of violations=19.52+0.12*AGE+(−0.65)*MALE+(−0.11)*EDU+(−0.09)*AUDIT+(−2.78)*EXPERT+0.11*FEEDBACK+(−0.78)*TIME+ε, where covariates are evaluated at: AGE=30.7, MALE=.44, EDU=17.2 and AUDIT=6.1

Table 2 also shows that regardless of the source of feedback received (expert or community group), there were no differences in the mean number of violations attributed to the six ads. Whether the experts received feedback from their own group or the community group, their Time 2 ratings were virtually the same (16.9 vs. 17.0). Similarly, community participants’ ratings at Time 2 were not affected by the source of feedback they received (19.8 vs. 19.7).

We examined Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) in the multiple regression model to investigate whether high Pearson correlations (Age vs. Expert status, 0.73; Years of education vs. Expert Status, 0.77) introduced multicollinearity in the model. We found VIFs for Expert status, Age, and Years of education to be 3.11, 2.57 and 2.76, which were well below the level of 10 considered to indicate multicolliearity (Belsley et al., 1980). We decided to keep both Age and Years of education in the model because the effect of Expert status appeared to be confounded (β =−0.56 in univariate regression, p=0.25) when not controlling for these covariates. We also performed sub-group comparisons across the four groups of experts in our model using alcohol research professionals (Expert group 4) as the reference group. Controlling for the above covariates, the estimates for the three dummy group-type variables were β =−0.51 (p=0.62) for the mental health professionals, β =0.46 (p=0.64) for the marketing and communication experts, and β =−1.60 (p=0.12) for the health and human development experts. None of the three respective group-by-time interaction terms were statistically significant. We also evaluated other aspects of group composition, including age, sex, education, and AUDIT score, within both the expert group and the community group. Although the older panel members in the expert group reported significantly more violations, none of the other variables was significant.

The number of violations identified at Time 1 was highly correlated with the number at Time 2 (Pearson r=0.73, p<.01). In a separate model examining the effects of feedback status as well as perceived violations at Time 1 on violations at Time 2 (Outcome variable), the number of violations identified at Time 1 was a significant predictor (β =0.66, p<.01). In a similar model where only the Time 2 data were used (N=286), feedback status did not have a significant effect (β =−0.23, p=0.64) on the mean number of violations at Time 2; nor did the group-by-feedback interaction term (β =0.13, p=0.86), controlling for the above-mentioned covariates.

We conducted a multivariate regression for the eight content-specific guidelines across the six ads. The results (Table 3) suggest that compared with the community sample, the smaller number of violations identified by the experts (β=−2.78, p<.01) in the adjusted model was mainly attributable to the smaller numbers of violations of Guideline 4 (β=−0.81, p<.01), Guideline 2 (β=−0.57, p<.01) and Guideline 3 (β=−0.42, p=0.05), controlling for the above covariates.

Table 3.

Effects of Expert status on eight content guidelines of the Beer Code based on multivariate regression

| Guideline and number | Estimate for expert status |

S.E. | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Humor…readily identifiable…by adults of legal drinking age | −.37 | .21 | .08 |

| 2. …portray beer in a responsible manner. | −.57 | .18 | <.01 |

| 3. …should avoid elements that appeal primarily to persons under the legal drinking age. | −.42 | .21 | .05 |

| 4. …should not make exaggerated product representation. | −.81 | .22 | <.01 |

| 5. …should not contain lewd or indecent language or images…portray sexually explicit activity… | −.30 | .18 | .10 |

| 6. …should not contain graphic nudity | −.01 | .08 | .85 |

| 8. …should not disparage competing beers. | −.20 | .15 | .19 |

| 9. …should not disparage anti-littering and recycling efforts. | −.12 | .15 | .43 |

Based on that the fact that both the Delphi technique and industry self-regulation procedures are based on experts’, we used the experts’ data (N=139) in our next analysis, which was to assess an appropriate size of the rater group. At Time 2, the average number of content violations per ad identified by an expert was 3.05, and the total variance of the number of the content violations was 2.16. We used Time 2 data from the experts because Time 2 data determines the number of content violations in actual panel rating situations. We ran a variance components model in R and found that the variance from the experts was 0.57 (about 27% of total variance) and the variance from the ads was 0.81 (about 38% of total variance). Figure 1 shows the mean number of violations per ad and the model-based variance from the experts as a function of the number of experts (N). Visual inspection suggests suggested that the estimates of the mean number of violations per ad and the variance become stabilized fairly quickly, requiring a much smaller N than the total expert sample size in this study (N=139). Nevertheless, Figure 1 shows that fewer than 15 reviewers may lead to an inappropriate estimate of variance attributable to the experts (e.g., negative variance).

Figure 1.

95% confidence intervals (with bootstrapped standard errors) for the model-based variance from 139 expert raters

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop both methodological tools and empirical findings that will enhance the ability of regulatory agencies and public interest monitoring groups to file complaints against companies that do not follow the alcohol industry’s self-regulation codes for responsible advertising. Unlike industry procedures, which often rely on the subjective judgments of paid consultants (Gomes and Simon, 2008), our procedure consists of quantitative rating scales having sound psychometric properties that have been systematically developed using standard psychological testing procedures (Babor et al., 2008).

The findings showed first that the Delphi technique works as expected in terms of achieving greater consensus in ratings designed to measure the presence or absence of a code violation in an alcohol ad. A second finding is that community participants’ feedback is less useful than experts’ feedback in developing consensus (reduced variance). Consistent with our hypothesis, expert raters were more influenced by feedback from their own group than the community group feedback. Moreover, the type of group feedback does not alter raters’ evaluation of the overall content violations at mean levels at Time 2 (see Table 2). Thus, feedback influenced consensus but not the number of violations reported.

One explanation could be that viewers’ evaluation at Time 1 was consistent with the content shown in the ad; therefore the role of feedback at Time 2 served only as an enhancement by guiding the second rating to be made with less overall variability. This could have happened by reducing the number of extreme ratings on the five-point Likert scale. Such enhancement was less salient for experts receiving feedback from the community group, perhaps due to the training and experience of the expert viewers. This finding suggests that experts may be better judges of code violations in programs monitoring alcohol advertising. We found experts identified fewer violations than the community participants in both sessions across the six ads and that Guidelines 2 (portray beer in a responsible manner), 3 (avoid appeals to underage individuals) and 4 (exaggerated product claims) contributed most to the difference. As indicated in Table 3, raters were similar on their evaluation of guidelines based on objective, “manifest content” (e.g. graphic nudity), but differed in their ratings of “latent content” (Graber, 1989), perhaps because the latter require interpretations that are affected by age, education and culture (Austin et al., 2007). It thus appears that the experts may have utilized their expertise in a conservative manner as compared to the community group, although the difference in the number of the identified violations was small. This is consistent with research showing that the content of alcohol ads may be viewed differently by trained and untrained adolescent raters, and that the latter may perceive more frequent portrayals of underage individuals, more appeal to underage drinkers, more frequent sexual connotations, and more frequent messages that encourage drinking (Austin et al., 2007). These findings suggest that the industry-appointed expert panels used to evaluate code violations in self-regulation schemes should include untrained adolescent viewers to inform the expert raters about the perceived meaning of advertising messages from the perspective of the message receivers.

The exploration of group differences among different professional groups indicated that the experts were very similar in the number of violations they detected and the type of guideline violation that was identified. To the extent that no differences were observed across these professional groups, group composition should not be a concern in the appointment of panel members. However, the present study was not designed to include a group of raters employed or paid by the alcohol industry, so it is unknown whether the findings would generalize to raters who may have a financial conflict of interest.

A final set of analyses explored the minimal number of raters necessary to obtain reliable estimates of code violations. Most rating panels assembled by the alcohol industry to evaluate complaints about code violations are composed of 3 to 5 raters (Beer Institute, 2011; Mosher, 2006). Our results suggest that this number may be too small, especially in the context of untrained raters who are using unvalidated qualitative procedures based on their own interpretation of self-regulation such as the US Beer Code. Perhaps reliability would improve with practice, but our results indicate that a rating panel composed of approximately 15 raters is necessary to obtain reliable estimates of code violations using our objective rating scales.

The research described in this study has the potential to advance the methodology (e.g., Delphi technique, panel member composition, number of panellists) needed to evaluate the adherence of beer, malt liquor, wine and distilled spirits ads to industry self-regulation content guidelines, and to provide empirical data about conformance with these guidelines. Given recent calls by the FTC, the Institute of Medicine, the World Health Organization and industry representatives themselves for independent, third party monitoring and evaluation of compliance, the methodology developed in this study should be useful in providing a tool for more systematic evaluation. This research should also lead to a better understanding of the extent to which industry guidelines can be measured across diverse groups of viewers (i.e., experts and vulnerable groups). If certain guidelines (e.g., should not make exaggerated product representation) are found difficult to obtain consensus, this would suggest areas where industry codes should be revised. Beyond the development of a useful methodology to evaluate industry codes, the web-based procedure can be used to conduct prevalence studies of code violations according to exposure markets, industry segments and time trends. The evaluation procedures are efficient enough to be applied quickly to newly developed advertisements. The information can be summarized and reported to the industry, public health authorities and the public to increase awareness of the possible effects of irresponsible advertising.

In summary, the results suggest that a consensus method like the Delphi technique could enhance the validity and credibility of an objective advertising code rating procedure such as the one we have developed.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA015383). The authors would like to thank Dr. Dwayne Proctor for his contributions to earlier stages of this project, and Dean Alfred Carter for facilitating recruitment of research participants.

References

- Anderson P. The impact of alcohol advertising: ELSA project report on the evidence to strengthen regulation to protect young people. Utrecht: National Foundation for Alcohol Prevention; 2007. [Accessed June 9, 2008]. Available at: http://www.stap.nl/content/bestanden/elsa_4_report_on_impact.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Pinkleton BE, Hust SJ, Miller AC. The locus of message meaning: Differences between trained message recipients in the analysis of alcoholic beverage advertising. Commun Methods Meas. 2007;1:91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in Primary Care. 2nd edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Xuan X, Damon D. Changes in the self-regulation guidelines of the US beer code reduce the number of content violations reported in TV advertisements. Journal of Public Affairs. 2010;10:6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Xuan Z, Proctor DC. Reliability of a rating procedure to monitor industry self-regulation codes governing alcohol advertising content. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:235–242. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer Institute. Advertising and Marketing Code. Washington, DC: Beer Institute; 2006. [Accessed May 11, 2007]. 2006 Available at: www.beerinstitute.org. [Google Scholar]

- Beer Institute. [Accessed September 27, 2012];Code Compliance Review Board: 2010–2011 Annual Report. 2011 Available at: http://www.beerinstitute.org/BeerInstitute/files/ccLibraryFiles/Filename/000000001188/BeerInstitute_CCRB_2010_web.pdf.

- Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Wiley; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie RJ, O’Connell ME, editors. Reducing underage drinking: A collective responsibility. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Accessed June 10, 2008]. 2004. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter I, Adams A, Shekelle P. Impact of varying panel membership on ratings of appropriateness in consensus panels: A comparison of a multi- and single disciplinary panel. Health Serv Res. 1995;30:577–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage Sci. 1963;9:458–467. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JM, Kelly RF. Self-regulation in the alcohol industry: A review of industry efforts to avoid promoting alcohol to underage consumers. [Accessed May 14, 2008];Federal Trade Commission Report. 1999 Available at: http://www.ftc.gov/reports/alcohl/alcoholreport.htm.

- Everett A. Piercing the veil of the future. A review of the Delphi method of research. Prof Nurse. 1993;9:181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes L, Simon M. [Last accessed 10/17/12];Why Big Alcohol Can't Police Itself: A Review of Advertising Self-Regulation in the Distilled Spirits Industry, Marin Institute 2008. 2008 http://www.marininstitute.org/images/stories/pdfs/08mi1219_discus_10.pdf.

- Graber DA. Content and Meaning: What’s It All About. Am Behav Sci. 1989;33:144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Center for Alcohol Policy (ICAP) ICAP Reports 9: Self-regulation of beverage alcohol advertising. Washington, DC: International Center for Alcohol Policy; 2001. [Accessed June 2, 2008]. 2001. Available at: http://www.icap.org/portals/0/download/all_pdfs/icap_reports_english/report9.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, Donovan RJ. Self-regulation of alcohol advertising: is it working for Australia? J Public Affairs. 2002;2:153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, Sanderson CF, Black NA. What will happen to the quality of care with fewer junior doctors? A Delphi study of consultant physicians' views. J Coll Physicians Lond. 1992;26:36–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leape LL, Park RE, Kahan JP, Brook RH. Group judgments of appropriateness: The effect of panel composition. Qual Assur Health Care. 1992;4:151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher J. Alcohol Industry Voluntary Regulation of its Advertising Practices: A Status Report. [Accessed September 27, 2012];Center for the Study of Law and Enforcement Policy. 2006 February 2006. Available at: http://www.camy.org/washingtonupdate/industrycode.pdf.

- Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. 2002;41:376–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DC, Babor TF, Xuan Z. Effects of cautionary messages and vulnerability factors on viewers’ perceptions of alcohol advertisements. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:648–657. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;S12:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]