Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium causes self-limiting gastroenteritis in humans and a typhoid-like disease in mice that serves as a model for typhoid infections in humans. A critical step in Salmonella pathogenesis is the invasion of enterocytes and M cells of the small intestine via expression of a type III secretion system, encoded on Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1), that secretes effector proteins into host cells, leading to engulfment of the bacteria within large membrane ruffles. The in vitro regulation of invasion genes has been the subject of much scientific investigation. Transcription of the hilA gene, which encodes an OmpR/ToxR-type transcriptional activator of downstream invasion genes, is increased during growth under high-osmolarity and low-oxygen conditions, which presumably mimic the environment found within the small intestine. Several negative regulators of invasion gene expression have been identified, including HilE, Hha, and Lon protease. Mutations within the respective genes increase the expression of hilA when the bacteria are grown under environmental conditions that are not favorable for hilA expression and invasion. In this study, the intracellular expression of invasion genes was examined, after bacterial invasion of HEp-2 epithelial cells, using Salmonella strains containing plasmid-encoded short-half-life green fluorescent protein reporters of hilA, hilD, hilC, or sicA expression. Interestingly, the expression of SPI-1 genes was down-regulated after invasion, and this was important for the intracellular survival of the bacteria. In addition, the effects of mutations in genes encoding negative regulators of invasion on intracellular hilA expression were examined. Our results indicate that Lon protease is important for down-regulation of hilA expression and intracellular survival after the invasion of epithelial cells.

Diseases caused by infection with Salmonella species pose a health threat to humans worldwide. Different strains of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium cause gastroenteritis in humans and other warm-blooded animal species, while serovar Typhi is restricted to human hosts and causes typhoid fever. Virulence determinants can vary among Salmonella strains; however, all possess Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1), a 40-kb locus encoded at centisome 63, which allows the bacteria to invade host intestinal epithelial cells (7, 12-14, 28, 30, 33, 39-42, 51). This suggests that the invasion phenotype is crucial for the establishment of infection by Salmonella species in various host environments. The importance of SPI-1 in virulence is supported by experimental evidence, as mutations in invasion genes cause ∼60-fold defects in the virulence of Salmonella within orally infected mice and abrogate symptoms of gastroenteritis, such as fluid secretion and polymorphonuclear leukocyte recruitment, in the calf model of infection (32, 53). SPI-1 encodes proteins that make up a type III secretion system (TTSS) responsible for the translocation of effectors that alter signaling mechanisms and mediate cytoskeletal rearrangements into the host cell, leading to the formation of large membrane ruffles that engulf the bacteria in vacuoles (70). Once inside host cells, genes from SPI-2 are expressed (11, 44, 48). SPI-2 is a 40-kb segment of the chromosome, located at centisome 30, that encodes a separate TTSS and secreted effectors that alter endocytic trafficking events within epithelial or macrophage cells so that lysosomal contents and NADPH oxidase are prevented from targeting the Salmonella-containing vacuole (9, 31, 61, 66, 67). This allows intracellular proliferation, which is crucial for Salmonella virulence within the mouse model (11, 60, 61). After initial invasion and destruction of intestinal M cells and enterocytes, host-adapted strains of Salmonella survive within macrophages, which carry the bacteria to the liver and spleen (40, 57). Unrestricted bacterial growth at these systemic sites leads to death of the host.

Salmonella expresses two distinct TTSSs involved in unique aspects of Salmonella pathogenesis (38). Therefore, there is much interest in understanding the differential regulation of these secretion systems. The SPI-1 TTSS and the invasive phenotype are expressed during growth under conditions that mimic those found in the lumen of the intestine, such as low oxygen tension and high osmolarity (24, 29, 45, 47). Expression of invasion genes is controlled by HilA, a member of the OmpR/ToxR-type transcriptional regulator family due to similarities in its DNA binding domain. HilA activates the transcription of SPI-1 invasion genes and effector proteins (5, 6, 46). The expression of hilA responds to the same environmental conditions that regulate the invasive phenotype, and overexpression of hilA from an exogenous promoter can overcome environmental regulation (6). Many mutations in bacterial genes that alter the positive or negative regulation of hilA have been identified. These include the positive regulators hilD, hilC, fis, sirA-barA, and csrAB (3, 23, 55, 58, 68). HilD is an AraC/XylS-type transcriptional regulator that binds to the hilA promoter and is essential for its activation. HilC has high homology to HilD and also binds to the hilA promoter; however, it is not required for hilA expression (58, 59). CsrA appears to regulate the levels of hilC and hilD mRNA within the bacteria (2). It is not clear how the SirA/BarA two-component regulatory system functions to regulate hilA expression. Several negative regulators have also been identified, including hha, hilE, ams, pag, and lon. Hha is a nucleoid-associated protein that is able to bind to the hilA promoter (26). HilE is a Salmonella-specific protein that may prevent the activation of hilA by protein-protein interactions with HilD (8, 25). It is not clear how RNase E (encoded by ams) and Pag function to regulate hilA expression. A mutation in the gene encoding Lon protease has been reported to increase hilA expression and invasion of tissue culture cells, and it causes severe defects in systemic virulence in the mouse model (64, 65).

Interestingly, in vitro expression of SPI-2 genes has been reported to occur only under growth conditions one would expect to find in the vacuolar environment, such as limiting nutrient concentration and acidic pH (18, 37, 48). Indeed, green fluorescent protein (GFP) and luciferase transcriptional reporters indicate that SPI-2 genes are expressed within macrophages and epithelial cells (11, 54). The expression of SPI-2 invasion genes and effector proteins is dependent upon the presence of the SsrA/SsrB two-component regulatory system encoded by SPI-2 (11, 18, 44). The environmental signals this system responds to are unknown. However, the transcription of ssrA-ssrB is dependent upon activation by OmpR, a response regulator protein that modulates gene expression in response to osmolarity conditions (44). In vitro experiments indicate that SPI-2 genes are not expressed under conditions that induce the expression of SPI-1 genes, and SPI-1 genes are not induced under conditions that activate the expression of SPI-2 (19, 20, 37, 43). These data suggest that the expression of SPI-1 invasion genes may be down-regulated after the invasion of epithelial cells. However, this has never been directly examined. In this study, we created short-half-life GFP reporters of SPI-1 invasion genes to examine the time course of expression after invasion of HEp-2 epithelial cells. Interestingly, we found that invasion gene expression is down-regulated and that this is important for the intracellular survival and proliferation of Salmonella.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. Bacteria were routinely grown in Luria broth (LB) (Gibco-BRL) containing the appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains used in fluorometer growth curves and invasion assays were grown in LB containing 1% NaCl to activate the expression of invasion genes.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 and derivatives | ||

| SL1344 | 69 | |

| JK20 | SL1344 with ssaV::cam | 31 |

| EE658 | SL1344 with hilA::Tn5lacZY-080 Tetr | 6 |

| BJ2473 | SL1344 with ΔhilE | This work |

| BJ2551 | SL1344 with pag::kan | This work |

| BJ2563 | SL1344 with ΔhilE Δhha | This work |

| BJ2565 | SL1344 with ΔURS | This work |

| BJ2584 | SL1344 with pag::Tn5 | This work |

| BJ3410 | SL1344 with lon-78::Tn10d-cam | This work |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 and derivatives | ||

| TT22291 | LT2 with lon-78::Tn10d-cam $DUP1731 [(leuA1179)MudJ(nadC220)] | John Roth |

| CJD359 | LT2 with ompR1009::Tn10 | 22 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pZC320 | Single-copy vector (mini-F origin); Ampr | 62 |

| pJB3 | pZC320 derivative carrying hilD driven by the lac promoter; Ampr | This work |

| pPROBE-gfp[ASV] | Promoterless tagged gfp vector plasmid; pBBR1 origin; Kanr | 50 |

| pPROBE-gfp | Promoterless gfp vector plasmid; pBBR1 origin; Kanr | 50 |

| pPhilA-gfp[ASV] | hilA promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp[ASV]; Kanr | This work |

| pPhilA-gfp | hilA promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp; Kanr | This work |

| pPhilD-gfp[ASV] | hilD promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp[ASV]; Kanr | This work |

| pPhilD-gfp | hilD promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp; Kanr | This work |

| pPhilC-gfp[ASV] | hilC promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp[ASV]; Kanr | This work |

| pPhilC-gfp | hilC promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp; Kanr | This work |

| pPssrA-gfp[ASV] | ssrA promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp[ASV]; Kanr | This work |

| pPssrA-gfp | ssrA promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp; Kanr | This work |

| pPsicA-gfp[ASV] | sicA promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp[ASV]; Kanr | This work |

| pPsicA-gfp | sicA promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp; Kanr | This work |

| pPrpsU-gfp[ASV] | rpsU promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp[ASV]; Kanr | This work |

| pPrpsU-gfp | rpsU promoter cloned into pPROBE-gfp[ASV]; Kanr | This work |

Tissue culture conditions and cell invasion assays.

HEp-2 tissue culture cells (52) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were passaged every 2 to 4 days as required. Invasion assays were conducted using previously described protocols (40, 53). Briefly, bacteria grown statically at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.4 to 0.5 (∼4.5 × 108 CFU/ml) were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection of 100 onto HEp-2 cell monolayers in 24-well plates and allowed to invade the cells for a 1-h incubation period. The cell monolayers were washed, and RPMI medium containing 100 μg of gentamicin/ml was added for an additional 90-min incubation period to kill extracellular bacteria. The cell monolayers were washed and lysed with 1% Triton X-100. Serial dilutions were made, and the bacteria released from the epithelial cells were plated onto L agar (Gibco/BRL) or L agar containing ampicillin. The number of CFU from the initial inoculum that survived the gentamicin treatment was expressed as percent invasion. To determine bacterial survival within HEp-2 cells, the infected cell monolayers, which were grown in RPMI medium containing gentamicin after the first hour of infection, were lysed 5 or 24 h after the initial inoculation.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of intracellular gene expression.

The protocol for invasion of HEp-2 epithelial cells by bacteria containing reporter fusions was identical to the assay described above, except that the monolayers were lysed 2.5, 5, or 24 h after the inoculation of bacteria. An hour after the initial inoculation with bacteria, the infected monolayers were grown in RPMI medium containing gentamicin for the duration of the infection. At the appropriate time, the medium was removed and the monolayers were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with Triton X-100. The HEp-2 cell lysate and released bacteria were collected and washed with 1% PBS to remove the Triton X-100 and stained for 20 min with a 1:100 dilution of Salmonella O group B antiserum (Becton Dickinson) in 1% PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin. The cell debris and bacteria were washed and stained for an additional 20 min with a 1:100 dilution of a secondary antibody, Cy 5-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Jackson Immunoresearch). The Cy 5 and GFP fluorescences of each sample were analyzed using FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson). Bacteria were identified by gating on the proportion of the population that was positive for Cy 5 staining. Lysed and stained uninfected HEp-2 cells were not Cy 5 positive, indicating that there was no cross-reactivity of the primary or secondary antibodies with HEp-2 cells. The GFP fluorescence of the Cy 5-positive population from infected HEp-2 cells was analyzed. The percentage of GFP-positive bacteria in each sample was determined by comparison to a negative control in each experiment. The negative-control sample was an aliquot of Salmonella containing the promoterless pPROBE vector that was stained with Salmonella-specific antibodies as described above. A histogram of GFP fluorescence for the negative-control sample was created, and the area of the histogram containing the bacterial population was gated and considered to be negative for GFP fluorescence. This gate was subsequently used to determine the percentage of GFP-positive bacteria from infected HEp-2 cells. By plating serial dilutions of the lysed HEp-2 cells after infection on L agar and L agar containing kanamycin, it was determined that 100% of the bacteria contained the reporter plasmid after 5 h and 85 to 100% of the bacteria contained the reporter plasmid after 24 h of infection.

Growth curve analysis of GFP reporter expression.

Dilutions (1:100) of overnight bacterial cultures were inoculated into L broth and grown with shaking at 37°C. At various times, 1-ml aliquots were taken and the OD600 was recorded. The aliquots were diluted to an OD600 of 0.3, and the GFP fluorescence level of the samples was measured using an Aminco-Bowman Series 2 luminescence spectrometer (SLM-Aminco Spectronic Instruments) with the excitation wavelength set at 475 nm and emission detection set at 515 nm (4). Control experiments determined that dilution of cultures to an OD600 of 0.3 results in approximately the same number of CFU on LB-kanamycin plates for aliquots taken at early time points in the growth curve and those taken at later time points. For example, after dilution to an OD600 of 0.3, aliquots of SL1344 carrying pPhilA-gfp taken at an OD600 of 0.4, 0.6, or 1.5 yielded 3.4 × 108, 4.1 × 108, or 3.5 × 108 CFU/ml, respectively.

Construction of reporter plasmids.

To construct the GFP reporter plasmids, the promoter regions of hilA, sicA, hilD, hilC, ssrA, and rpsU (837, 1,011, 1,002, 790, 1,000, and 358 bp upstream of the translation start sites, respectively) were PCR amplified and cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). The primers used to amplify each promoter (listed in Table 2) were designed to incorporate 5′ SalI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sites. The pGEM-T clones containing each promoter fusion were digested with SalI and EcoRI to release the promoter fragments. The promoter fragments were gel purified and cloned into the multicloning site of SalI/EcoRI-digested pPROBE-gfp[ASV] and pPROBE-gfp vectors upstream of the tagged or untagged promoterless gfp gene (50). All cloning procedures were performed with standard reagents according to standard protocols.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of primers used in this work

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| −496 hilA | 5′ GTCGACCAGATGACACTATCTCCTTCC 3′ |

| +350 hilA | 5′ GAATTCATAATAGTGTATTCTCTT 3′ |

| 5′ hilD | 5′ GTCGACGGATAATAGGTATCCAGCCAG 3′ |

| 3′ hilD | 5′ GAATTCGTTATTTTAATGTTCCTT 3′ |

| 5′ sicA | 5′ GTCGACATGGCTGACTACAGTTTG 3′ |

| 3′ sicA | 5′ GAATTCCATTACTTACTCCTGTTATCT 3′ |

| 5′ hilC | 5′ GTCGACAAGGTGATACCGGGTACGATT 3′ |

| 3′ hilC | 5′ GAATTCATCCTGTGTGCTATAAGGAAC 3′ |

| 5′ ssrA | 5′ GTCGACCCACTAAATGTAGCTGTT 3′ |

| 3′ ssrA | 5′ GAATTCAATGCTTCCCTCCAGTTG 3′ |

| 5′ rpsU | 5′ GTCGACGGCACTACGCCGCCGTAGTCA 3′ |

| 3′ rpsU | 5′ GAATTCGCATGTGCCTCTCACCTTTGA 3′ |

EcoRI and SalI sites are underlined.

P22 transduction.

Antibiotic-resistant gene insertions were moved between strains by transduction with P22 HT int as previously described (17). Transductants were selected on LB agar containing the appropriate antibiotic and 10 mM EGTA to prevent reinfection with P22.

Confocal imaging.

HEp-2 cells were seeded onto coverslips in 24-well plates and inoculated with Salmonella containing pPhilA-gfp[ASV] according to the invasion assay protocol described above. At 2.5, 5, or 24 h after infection, the cells were fixed on the coverslips with 4% formaldehyde, permeablized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and stained with 1 μg of ethidium bromide/ml, as well as anti-Salmonella antiserum and Cy 5-conjugated secondary antibody as described above. Confocal imaging of the infected cells was performed using a Bio-Rad MRC600 confocal scanning laser microscope.

RESULTS

The expression of SPI-1 promoter fusions is down-regulated within HEp-2 epithelial cells.

To examine the expression of virulence genes over time within Salmonella after the invasion of epithelial cells, plasmid transcriptional reporters of serovar Typhimurium hilA, sicA, hilD, hilC, ssrA, and rpsU promoters were created. The expression of hilA and hilD was examined because they encode important positive regulators of the invasive phenotype (6, 58). We also examined the expression of hilC, carried on SPI-1, which increases the expression of hilA and activates the expression of the SPI-1 invF operon independently of hilA when overexpressed (1, 23, 55, 58). The sicA gene, which encodes a chaperone, is the first gene in the sic-sip secreted-effector operon located on SPI-1, and its expression pattern should mimic that of hilA (15, 16, 42). The ssrA gene encodes the sensor kinase component of a two-component regulatory system necessary for the transcription of the TTSS and secreted effectors of SPI-2 (11). The promoter of the rpsU gene, which encodes the 30S ribosomal S21 protein, was chosen as a positive control, since this protein is synthesized constitutively during exponential-phase growth (21). These promoters were cloned upstream of a promoterless wild-type (wt) gfp gene, as well as a promoterless gfp gene that encodes a protein tagged at the C terminus with the avian sarcoma virus (ASV) peptide, on pPROBE plasmid vectors to create transcriptional reporter fusions (50). The GFP[ASV] protein is targeted for Tsp protease degradation within the bacteria and has been reported to have an ∼110-min half-life in E. coli, while untagged GFP is very stable (estimated in vivo half-life, >24 h) (4).

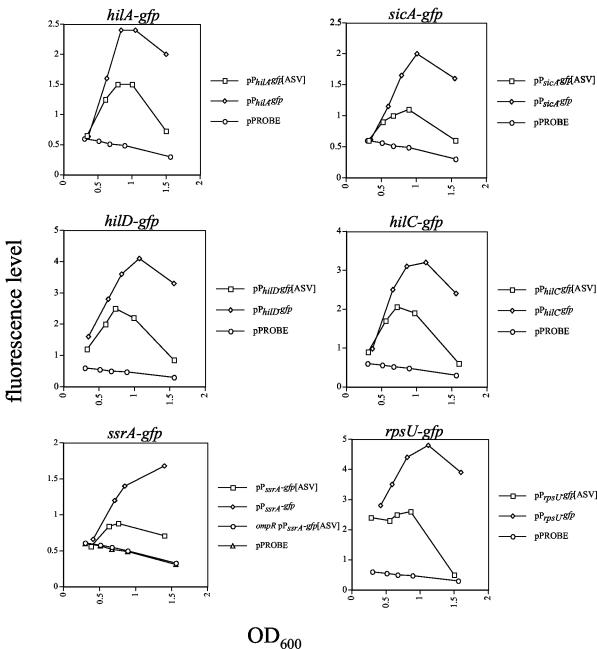

The plasmid reporter fusions were transformed into Salmonella, and the GFP fluorescence from each strain was recorded at different time points throughout a growth curve (Fig. 1). The pPROBE plasmid containing the untagged promoterless gfp was used as a negative control. The hilA, sicA, hilD, and hilC promoters all exhibited similar patterns of expression. During early exponential phase, the fluorescence level was quite low and, for hilA and sicA, undistinguishable from that of the negative control. The fluorescence level increased three- to fivefold during mid- to late exponential phase for the wt GFP reporters and two- to threefold for the short-half-life GFP reporters. Fluorescence levels decreased for each of these reporters during stationary phase. This is consistent with previous reports of the expression pattern of hilA (56). In contrast to the SPI-1 reporter fusions, a <2-fold increase in the level of ssrA expression from the short-half-life GFP reporter was noted, supporting previous reports that ssrA is not expressed well during growth in rich media. Also, the fluorescence level of the ssrA reporter fusions did not appear to decrease dramatically during stationary phase. The expression of the ssrA reporter was dependent upon the presence of OmpR, as fluorescence levels from an ompR mutant strain were indistinguishable from those of the negative control. Fluorescence levels from the short-half-life rpsU reporter strain did not vary during exponential growth. However, a sharp decrease in expression was recorded during stationary phase. This was expected, since levels of S21 protein synthesis decrease at lower growth rates and during the stringent response (21, 35). Interestingly, the fluorescence levels from strains containing the unstable (ASV-tagged) GFP reporters did not reach the same magnitude as the fluorescence levels from strains containing the stable (untagged) reporters. Additionally, while a decrease in the fluorescence level of the stable reporters was noted during stationary phase, this level was higher than the peak of fluorescence recorded for the unstable GFP reporters and did not diminish as sharply as those of the unstable reporters. Thus, GFP fluorescence recorded from the short-half-life GFP reporter strains did not accumulate to the same extent as that of the stable GFP reporters and is likely to reflect the actual transcription pattern of promoters in Salmonella.

FIG. 1.

Fluorescence levels from Salmonella containing GFP reporters at various times during a growth curve. The fluorescence levels shown represent one experiment that was repeated at least two times with similar results.

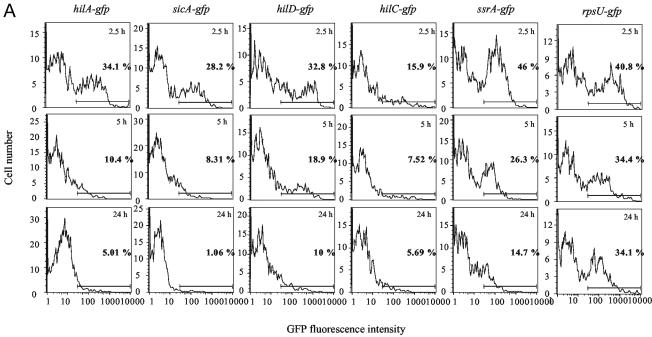

Strains containing the unstable GFP plasmid reporters were used to infect HEp-2 epithelial cells. After 2.5, 5, and 24 h of infection, the epithelial cells were lysed, processed as described in Materials and Methods, and analyzed for GFP fluorescence by FACS (Fig. 2A). The percentage of GFP-positive bacteria containing fusions to SPI-1 promoters decreased substantially from 2.5 to 24 h after infection. However, it is important to note that the decrease in fluorescence levels from the bacteria does not correspond to a decrease in the number of bacteria within the HEp-2 cells, as Salmonella cells containing the reporter plasmids replicate intracellularly from 2.5 to 24 h after infection (Fig. 2B and data not shown). An ∼7-fold drop in the percentage of GFP-positive bacteria occurred for the strain containing the hilA-gfp reporter, while an ∼26-fold decrease occurred for the strain containing the sicA-gfp reporter. The percentage of GFP-positive bacteria from infected HEp-2 cells decreased ∼3-fold from 2.5 to 24 h after infection for both the hilD and hilC reporter strains. Interestingly, HEp-2 cells containing the ssrA reporter strain exhibited the highest number of GFP-positive organisms, 46% at 2.5 h, compared to the other reporter strains. However, the percentage of GFP-positive organisms dropped ∼3-fold by 24 h after infection. Intracellular expression of ssrA was dependent upon the presence of functional OmpR (data not shown); 40.8% of bacteria containing the rpsU reporter were GFP positive after 2.5 h, and this number did not drop significantly (∼1.2-fold) during the course of infection, though the mean fluorescence intensity for GFP-positive bacteria did decrease slightly (∼1.8-fold) from 2.5 to 24 h after infection.

FIG. 2.

Expression of SPI-1 invasion genes decreases after infection of HEp-2 epithelial cells. (A) FACS analysis was performed after lysing of infected epithelial cells and stainingof intracellular Salmonella (see Materials and Methods) 2.5, 5, and 24 h after inoculation of bacteria onto HEp-2 cell monolayers. The percentage of GFP-positive bacteria and the length of infection are indicated on each histogram. The horizontal lines represent the gate used to determine the percentage of GFP-positive bacteria in each sample. (B) Confocal microscopy was performed on cell monolayers infected with Salmonella containing pPhilA-gfp[ASV] 2.5, 5, and 24 h after infection. After infection, samples were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with ethidium bromide, anti-Salmonella antiserum, and a secondary antibody conjugated to Cy 5. The top two micrographs show the same microscopic field 2.5 h after infection. Likewise, the middle and bottom micrographs show the same fields 5 and 24 h after infection, respectively. The micrographs on the left show the GFP fluorescence of bacteria within epithelial cells stained with ethidium bromide. The micrographs on the right show bacteria within the same fields as on the left stained with Salmonella-specific antibody and Cy 5 as a positive control for the presence of bacteria. The arrowheads point to bacteria that are expressing GFP and that are stained with Cy 5 in adjacent micrographs of the same field. The arrow in the lower left micrograph points to bacteria that are not expressing GFP (as no green fluorescence was detected); however, the diffuse (red) fluorescence that is visible is likely due to staining of the bacterial nucleic acids by ethidium bromide; the arrowhead in the lower right micrograph points to bacteria in the same area of the microscopic field that are stained with Cy 5.

The data presented in Fig. 1 are from one representative experiment in which GFP fluorescence rates from each reporter at each time point were analyzed simultaneously. These data represent the general trend of reporter expression at each time point after the infection of epithelial cells. However, some variation from experiment to experiment was observed (see Fig. 4 and compare with Fig. 2A); therefore, the average expression of each reporter at each time point from several individual experiments is reported in Table 3. The average GFP fluorescence from each reporter was also determined before the infection of epithelial cells for several experiments, and these are included as the zero time points. Similar to the data in Fig. 2A, a decrease in the expression of SPI-1 genes was observed after the percentages of GFP-positive bacteria in several experiments were averaged, although from 2.5 to 24 h after infection there was little average decrease in the numbers of GFP-positive bacteria containing the hilC and hilD reporters. We noted a higher percentage of GFP-positive bacteria containing each reporter at the zero time point before infection. This is not unexpected for bacteria containing SPI-1 gene reporters. The rpsU-gfp reporter had a higher percentage of GFP-positive cells prior to infection, which may reflect a decrease in transcription of the rpsU promoter after infection, possibly due to differences in growth rates or nutritional conditions within the intracellular environment compared to exponential-phase growth in rich medium prior to infection. However, the percentage of GFP-positive cells containing the reporter decreased little from 2.5 to 24 h after infection, suggesting that transcription of the rpsU promoter remains steady over time within HEp-2 cells. Interestingly, the ssrA-gfp reporter also had a higher percentage of GFP-positive organisms prior to infection, which differs from previous reports of the extracellular expression of this gene.

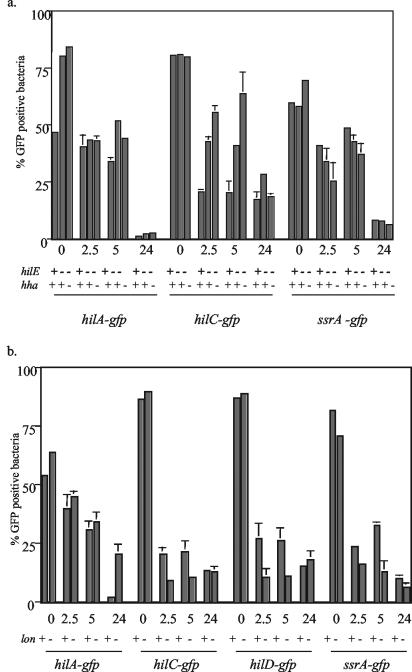

FIG. 4.

Effects of mutations in negative regulators on the expression of GFP reporters after infection of HEp-2 epithelial cells. FACS analysis was performed 2.5, 5, or 24 h after infection of epithelial cells with Salmonella hilE or hilE hha (a) and lon (b) mutant strains containing unstable (tagged) hilA, hilD, hilC, or ssrA-gfp reporters. The data presented are the mean plus the standard deviation of one experiment performed in duplicate that is representative of several independent experiments that had similar results. +, present; −, absent.

TABLE 3.

Reporter expression after infection of epithelial cells

| Reporter | % GFP-positive bacteria at indicated times (h)a

|

Decrease (n-fold)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0b | 2.5 | 5 | 24 | 0-24 h | 2.5-24 h | |

| hilA-gfp | 56.6 ± 22.9 | 30.8 ± 11.5 | 20.4 ± 9.8 | 13.2 ± 11.2 | 4.3 | 2.3 |

| sicA-gfp | 43.8 | 31.2 ± 5.2 | 12.2 ± 6.6 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 17.5 | 12.5 |

| hilD-gfp | 67.2 ± 18.8 | 29.1 ± 11.6 | 22.3 ± 8.88 | 17.2 ± 10.2 | 3.9 | 1.7 |

| hilC-gfp | 76.9 ± 14.1 | 14.9 ± 4.9 | 12.9 ± 7.8 | 8.8 ± 4.9 | 8.7 | 1.7 |

| ssrA-gfp | 70.7 ± 19.9 | 37.2 ± 12.4 | 30.5 ± 13.9 | 11.2 ± 7.2 | 6.3 | 3.3 |

| rpsU-gfp | 76.1 ± 30.6 | 49.7 ± 9.1 | 33.6 ± 5.0 | 29.2 ± 7.5 | 2.6 | 1.7 |

Average and standard deviation for GFP-positive bacteria before (0) or after infection for at least three separate experiments (0 time point for sicA was tested only one time).

Average for GFP-positive bacteria within the inoculum before infection of HEp-2 cells.

To confirm that GFP fluorescence from the hilA reporter strain diminished during infection, confocal microscopy of infected cells was performed (Fig. 2B). After 2.5 h of infection, intracellular bacteria were bright green. However, after 5 h of infection the GFP fluorescence appeared dimmer, and after 24 h virtually no GFP-positive bacteria could be detected. Intracellular bacteria were stained with Salmonella-specific antibodies and visualized within the HEp-2 cells at each time point to confirm that bacteria were present within the cells.

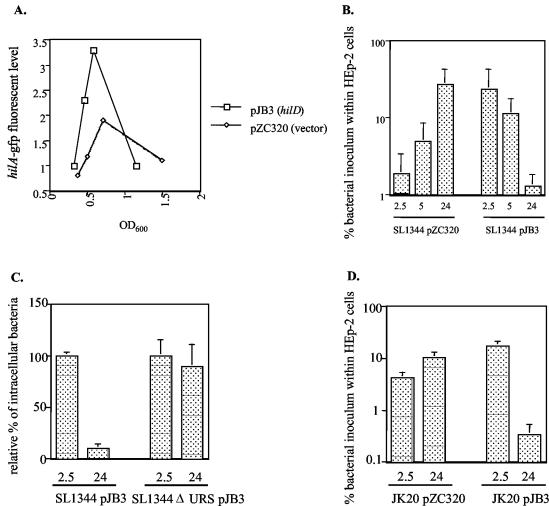

Plasmid expression of hilD increases bacterial invasion but decreases intracellular growth and survival.

Since the expression of SPI-1 invasion genes appears to be down-regulated after infection of epithelial cells, the trait may be important for intracellular growth and survival. This possibility was examined by expressing plasmid pJB3, which carries hilD expressed from the lac promoter, in wt Salmonella to ectopically increase the expression of hilA and SPI-1 invasion genes in a dysregulated fashion. Using β-galactosidase reporters, hilD carried on plasmids has previously been shown to increase hilA expression (58). Consistent with these results, pJB3 increased the level of GFP fluorescence from the hilA-gfp plasmid reporter strain, compared to wt hilA-gfp expression during exponential growth (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, we found that expression of pJB3 caused an ∼12-fold increase in the invasion of HEp-2 cells compared to that by the wt strain containing the vector plasmid, pZC320 (Fig. 3B). However, while the numbers of intracellular Salmonella cells containing pZC320 increased ∼15-fold from 2.5 to 24 h after infection, due to bacterial replication, the strain containing pJB3 did not appear to replicate, and the number of intracellular bacteria decreased ∼18-fold. This suggests that the ability to down-regulate hilA and invasion gene expression is important for the intracellular survival and proliferation of Salmonella. However, the overexpression of hilD could have a toxic effect on intracellular bacteria that is independent of hilA expression. Therefore, we examined the survival of a Salmonella pJB3 strain containing a ΔURS mutation in the hilA promoter that deletes the HilD binding site and abrogates hilA expression and invasion (Fig. 3C) (10). Since this strain is unable to invade, we coinfected with wt Salmonella, which allows the invasion-deficient bacteria to be engulfed in epithelial cells within membrane ruffles that are elicited by invasive wt Salmonella (endocytic trafficking of Salmonella-containing vacuoles which harbor SPI-1 mutant or wt bacteria has been shown to be similar at early time points after infection) (27, 63). Interestingly, the numbers of intracellular Salmonella ΔURS containing pJB3 did not decrease during the course of the infection. This indicates that the intracellular-survival defect caused by pJB3 expression is due to a HilD-mediated increase in expression of SPI-1 invasion genes, or possibly some other unknown HilA-regulated gene. We noted that the number of intracellular bacteria containing the ΔURS mutation did not increase after 24 h of infection. This is consistent with a recent report by Steele and colleagues that an SPI-1 invA mutant is not able to grow within epithelial cells (63).

FIG. 3.

Plasmid expression of hilD increases bacterial invasion but decreases intracellular growth and survival. (A) Expression of hilA was estimated by determining the fluorescence level from Salmonella strain SL1344 pPhilA-gfp[ASV] carrying pJB3, which expresses hilD from the lac promoter, or the parent vector pZC320 at various times during a growth curve. The data shown are from one experiment that is representative of two separate experiments performed with similar results. (B) An invasion assay was performed with SL1344 containing pZC320 or pJB3 to determine invasion and intracellular survival of the bacteria from 2.5 to 24 h after infection. (C) Invasion and intracellular survival of SL1344(pJB3) and SL1344 ΔURS(pJB3) were determined. Since SL1344 ΔURS is noninvasive, the SL1344 ΔURS(pJB3) strain was coinfected with wt Salmonella that did not contain pJB3. The percentage of the original inoculum of each strain containing pJB3 that was recovered on LB-ampicillin plates after 2.5 h of infection was set to 100% for each strain, and the number of intracellular bacteria containing pJB3 at 24 h is reported as a percentage of that shown at 2.5 h. (D) Invasion and intracellular survival of the SPI-2 ssaV::cam mutant strain, JK20, carrying pZC320 or pJB3 after 2.5 or 24 h of infection. The invasion assay data are the mean plus the standard deviation of one experiment performed in triplicate that is representative of two or more independent experiments.

Since the expression of SPI-1 genes is down-regulated in epithelial cells and many reports have established that SPI-2 genes are expressed within host cells, it is possible that both the SPI-1 and SPI-2 TTSSs are being expressed intracellularly in bacteria expressing pJB3. We hypothesized that the expression of two functional TTSSs may be harmful to the bacteria (perhaps by perturbing the integrity of the membrane) and may cause the intracellular-survival defect in strains carrying pJB3. To test this hypothesis, invasion and survival of the Salmonella SPI-2 mutant strain, JK20, containing an ssaV::cam mutation and plasmid pJB3, were examined (Fig. 3D). SsaV is a component of the SPI-2 type III secretion apparatus and is required for the secretion of SPI-2 effectors, SseC and SseD (36, 43). Strain JK20 containing pJB3 was able to invade more efficiently than JK20 containing pZC320. JK20(pZC320) did not replicate well within the epithelial cells, which is a phenotype that has been reported previously for strains containing mutations in SPI-2 (11, 37, 66). However, JK20(pJB3) exhibited a survival defect similar to wt Salmonella carrying pJB3. This suggests that the simultaneous expression of functional SPI-1 and SPI-2 secretion systems is not responsible for the intracellular-survival defect in strains expressing pJB3.

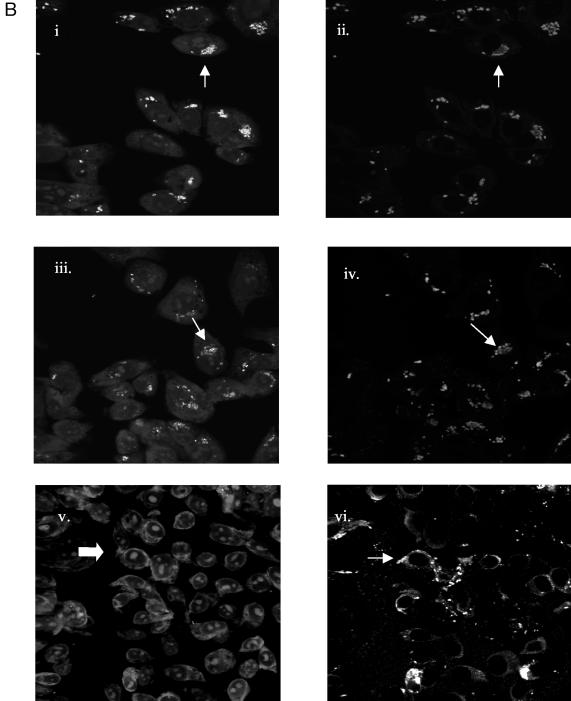

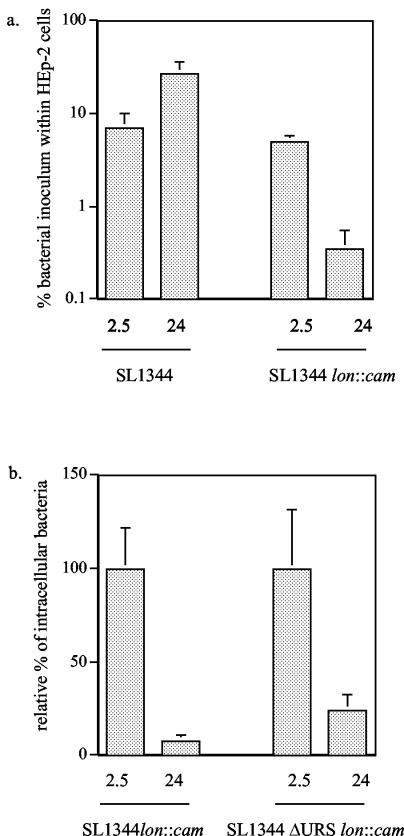

A mutation in lon increases hilA expression within epithelial cells, but mutations in hilE and hha do not.

To determine if negative regulators play a role in decreasing the expression of SPI-1 invasion genes during infection of epithelial cells, plasmid gfp reporters were transformed into Salmonella strains containing hilE, hilE hha, pag, or lon mutations. These strains were used to infect HEp-2 epithelial cells for 2.5, 5, and 24 h. Subsequently, the cell monolayers were processed and analyzed by FACS. The bacterial GFP fluorescence was analyzed before infection and is shown as the zero time point. Figure 4a shows the percentage of GFP-positive bacteria containing mutations in hilE or hilE hha at each time point for the hilA, hilC, and ssrA reporters. Mutations in hilE and hha caused ∼1.7-fold-increased numbers of GFP-positive organisms compared to the wt containing the hilA reporter before infection of HEp-2 cells. However, the percentage of GFP-positive bacteria decreased to the same levels as the wt strain after infection, so that by 24 h only 1 to 2% of the bacteria were GFP positive. Interestingly, the percentage of GFP-positive bacteria containing the hilC reporter increased after infection due to mutations in hilE and hha. However, the increase in hilC expression did not correspond to increased levels of hilA expression, as evidenced by the numbers of GFP-positive organisms within populations containing the hilA reporter. Previous experiments indicated that mutations in hilE and hha do not affect the expression of hilD, and similar results were observed for the hilD-gfp reporter (data not shown) (10).

The effects of the lon mutation on expression of hilA, hilC, hilD, and ssrA reporters after infection of epithelial cells were also examined (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, while the percentage of GFP-positive wt bacteria containing the hilA reporter decreased ∼20-fold from 2.5 to 24 h after infection, a minimal decrease of ∼2-fold was observed for the lon mutant strain. Thus, the lon mutation increased hilA expression 10-fold compared to the wt strain after 24 h of infection. The lon mutation resulted in an ∼2-fold decrease in the percentage of GFP-positive organisms containing the hilC and hilD reporters 2.5 and 5 h after infection. A similar decrease was observed for bacteria containing the ssrA reporter 5 h after infection. However, 24 h after infection, the percentages of GFP-positive bacteria containing the hilC, hilD, and ssrA reporters were approximately equal for the lon and wt strains.

The lon mutation decreases intracellular survival.

Since the lon mutation resulted in increased levels of hilA expression after infection of HEp-2 cells, this could result in a defect in intracellular growth and survival. Invasion and survival of the lon mutant strain were compared to those of the wt strain 2.5 and 24 h after infection (Fig. 5a). We found that the lon mutant strain invaded HEp-2 cells with approximately the same efficiency as the wt strain. This differs from the increased invasion observed for the lon mutant strain reported by Takaya and colleagues, which may reflect the fact that a different serovar Typhimurium strain was used in this study (65). Previous work in our laboratory indicated that mutations in negative regulators of hilA do not increase invasion beyond that observed for the wt strain in SL1344, unless the bacteria are grown under conditions that are nonactivating for invasion (8, 26). However, a significant decrease in the number of intracellular bacteria was observed at the 24-h time point for the lon mutant strain. A possible explanation for this outcome is that the lon mutant strain is toxic to HEp-2 cells so that the HEp-2 cells were lysed and released bacteria into the extracellular medium, where they would be killed by gentamicin and washed away prior to enumeration. To examine this possibility, trypan blue staining of HEp-2 cell monolayers infected with either the wt or lon strain was performed, and no significant difference in the number of live HEp-2 cells was observed after 24 h of infection (2.8 × 105 ± 0.79 × 105 compared to 2.2 × 105 ± 0.44 × 105 live HEp-2 cells per well after infection with the wt and lon strains, respectively, counted in six wells each). This experiment indicates that the lon strain is no more toxic to HEp-2 cells than wt Salmonella. Thus, the lon strain appears to have an intracellular-survival defect, which may be due to unregulated expression of hilA. To test this idea, we determined the intracellular survival of SL1344 ΔURS containing the lon mutation after coinfection with wt SL1344 (Fig. 5b). Similar to SL1344 lon::cam, the SL1344 ΔURS lon::cam strain also exhibited an intracellular-survival defect. However, we consistently observed ∼3-fold more intracellular SL1344 ΔURS lon::cam bacteria than SL1344 bacteria containing a mutation in lon alone after 24 h of infection. This suggests that the intracellular-survival defect observed for the lon mutant strain is partially due to an inability to down-regulate hilA expression.

FIG. 5.

Effects of a lon mutation on invasion and intracellular survival of Salmonella. Invasion and intracellular survival of Salmonella strain SL1344 containing a lon::cam mutation 2.5 and 24 h after infection were determined and compared to those of wt Salmonella. The data shown are the mean plus the standard deviation of one experiment performed in triplicate that is representative of two separate experiments with similar results.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to determine how SPI-1 invasion genes are regulated after the invasion of host cells. To accomplish this goal, we created short-half-life GFP transcriptional reporters and examined their expression at different times after invasion. Interestingly, SPI-1 genes were down-regulated after invasion. The hilA and sicA reporters were down-regulated most severely, as very few intracellular bacteria containing these reporters were GFP positive 24 h after infection. The hilD and hilC reporters were also down-regulated, but to a lesser extent. A larger percentage of GFP-positive organisms carried the ssrA reporter 2.5 h after infection, which is consistent with reports that SPI-2 genes are expressed in the intracellular Salmonella-containing vacuole (11, 54). Previously, FACS analysis of the expression of an ssrA-gfp reporter fusion within macrophages indicated that ssrA expression was off before infection and increased from 1 to 6 h after infection in an OmpR-dependent manner (11). Similarly, our experiments indicate that intracellular expression of the ssrA reporter is dependent on the presence of OmpR. In contrast, however, we observed a higher percentage of GFP-positive bacteria prior to infection and an ∼3-fold decrease in GFP-positive bacteria after 24 h of infection. The differences in these results may be due to different plasmid reporter constructions (the GFP[ASV] reporter used in this study is constantly degraded, so that GFP protein does not build up), different host cell types (epithelial cells versus macrophages), different methods of reporting FACS data (our study reports the percentage of GFP-positive bacteria within a sample in comparison to a negative control, while other studies have reported peak fluorescence intensity), or a combination of these possibilities. However, there does not appear to be a general repression or proteolysis of reporter fusions in the intracellular environment, as the percentage of GFP-positive organisms containing the rpsU-gfp reporter did not drop significantly after 24 h.

Since the expression of SPI-1 genes is down-regulated after infection of HEp-2 cells, we hypothesized that this trait is important for intracellular growth and survival. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that plasmid overexpression of hilD, which increased hilA expression in a dysregulated fashion, caused a survival defect that was dependent on a functional hilA promoter. This suggests that an inability to down-regulate the expression of SPI-1 genes after the invasion of host cells is harmful for Salmonella. However, recent evidence indicates that a functional SPI-1 type III secretion apparatus is necessary for intracellular growth of Salmonella (63). It is possible that crucial effector proteins are secreted though the SPI-1 TTSS, before the SPI-2 system is expressed, which are needed for Salmonella growth. One class of constitutively expressed proteins, including SlrP and SspHI, are secreted through both the SPI-1 and SPI-2 systems (48, 49). It is interesting to speculate that unidentified members of this class that may be necessary for intracellular growth are secreted through the SPI-1 system at early times and through the SPI-2 system later during infection. Alternatively, an effector that is exclusively secreted through the SPI-1 TTSS during early infection may be required for intracellular replication. Regardless, unregulated expression of SPI-1 invasion genes eventually becomes lethal for the bacteria. Our experiments here indicate that this is not due to the simultaneous expression of both SPI-1 and SPI-2 secretion systems.

To determine how SPI-1 genes are down-regulated in the intracellular environment, we determined the effects of mutations in negative regulators of invasion genes on the expression of reporter fusions after infection of epithelial cells. We found that hilA expression is down-regulated after invasion in strains containing mutations in hilE and hha. This is interesting, since mutations in these genes result in an ∼5-fold increase in hilA expression from β-galactosidase reporters under in vitro growth conditions (10). This may indicate that hilE and hha are primarily responsible for the repression of hilA in the extracellular environment before Salmonella finds the appropriate conditions to initiate invasion. However, mutations in hilE and hha resulted in increased levels of hilC after infection of Hep-2 cells, which apparently did not result in increased levels of hilA expression. It would be interesting to determine how HilE and Hha regulate hilC intracellularly (is the mechanism similar to hilA regulation?) and what role hilC regulation plays during intracellular growth of Salmonella. Interestingly, we found that a mutation in lon caused an ∼10-fold increase in the expression of hilA compared to the wt after 24 h of infection, as well as a significant survival defect that was partially dependent upon hilA expression. This suggests that Lon protease activity indirectly represses hilA expression and allows the bacteria to survive and proliferate within host cells. However, it is likely that Lon is involved in other processes within the bacteria that are crucial for intracellular survival as well. Lon degrades the majority of abnormal proteins within bacteria and also specifically recognizes and degrades certain regulatory proteins, such as RcsA, a positive regulator of capsular biosynthesis (34).

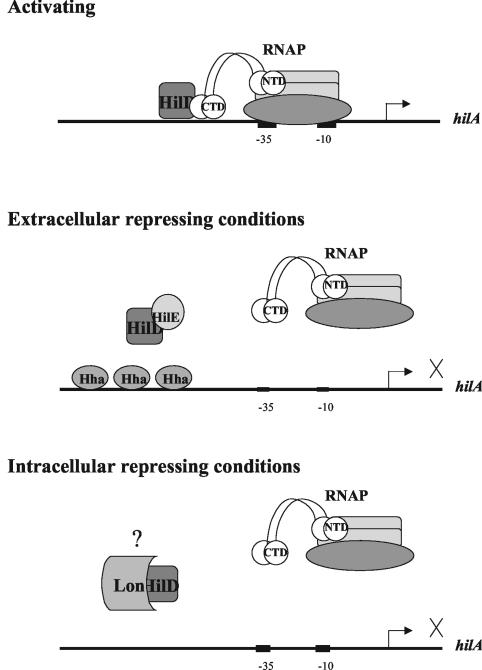

The work presented in this paper builds upon an evolving model of hilA and SPI-1 invasion gene regulation (Fig. 6). Previous work in our laboratory suggested that HilD activates the expression of hilA by direct contact with the α C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase (10). HilE and Hha may block this activation by binding to HilD and the hilA promoter, respectively, under extracellular repressive conditions for invasion (8, 26). The results of this study allow us to speculate that Lon may degrade the hilA activator protein, HilD, to posttranscriptionally regulate its activity and decrease the level of hilA expression during intracellular growth of Salmonella. Future work will be aimed at precisely defining which hilA regulatory protein is degraded by Lon protease to shut off intracellular hilA expression.

FIG. 6.

Model of hilA regulation under conditions that are activating for invasion and conditions that are repressive for invasion. CTD, C-terminal domain; NTD, N-terminal domain.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Lindow for the plasmid vectors encoding shortened-half-life GFP constructs and J. Roth for the lon mutant strain TT22291. We also thank Nate Ledeboer for assistance with confocal microscopy.

The work described here was supported by NIH grant AI38268 to B.D.J.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

REFERENCES

- 1.Akbar, S., L. M. Schechter, C. P. Lostroh, and C. A. Lee. 2003. AraC/XylS family members, HilD and HilC, directly activate virulence gene expression independently of HilA in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 47:715-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altier, C., M. Suyemoto, and S. D. Lawhon. 2000. Regulation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasion genes bycsrA. Infect. Immun. 68:6790-6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altier, C., M. Suyemoto, A. I. Ruiz, K. D. Burnham, and R. Maurer. 2000. Characterization of two novel regulatory genes affecting Salmonella invasion gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 35:635-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen, J. B., C. Sternberg, L. K. Poulsen, S. P. Bjorn, M. Givskov, and S. Molin. 1998. New unstable variants of green fluorescent protein for studies of transient gene expression in bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2240-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajaj, V., C. Hwang, and C. A. Lee. 1995. hilA is a novel ompR/toxR family member that activates the expression of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes. Mol. Microbiol. 18:715-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj, V., R. L. Lucas, C. Hwang, and C. A. Lee. 1996. Co-ordinate regulation of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes by environmental and regulatory factors is mediated by control of hilA expression. Mol. Microbiol. 22:703-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumler, A. J., R. M. Tsolis, T. A. Ficht, and L. G. Adams. 1998. Evolution of host adaptation in Salmonella enterica. Infect. Immun. 66:4579-4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baxter, M. A., T. F. Fahlen, R. L. Wilson, and B. D. Jones. 2003. HilE interacts with HilD and negatively regulates hilA transcription and expression of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium invasive phenotype. Infect. Immun. 71:1295-1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beuzon, C. R., S. Meresse, K. E. Unsworth, A. J. Ruiz, S. Garvis, S. R. Waterman, T. A. Ryder, E. Boucrot, and D. W. Holden. 2000. Salmonella maintains the integrity of its intracellular vacuole through the action of SifA. EMBO J. 19:3235-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boddicker, J. D., B. M. Knosp, and B. D. Jones. 2003. Transcription of the Salmonella invasion gene activator,hilA, requires HilD activation in the absence of negative regulators. J. Bacteriol. 185:525-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cirillo, D. M., R. H. Valdivia, D. M. Monack, and S. Falkow. 1998. Macrophage-dependent induction of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system and its role in intracellular survival. Mol. Microbiol. 30:175-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collazo, C. M., and J. E. Galán. 1997. The invasion-associated type III system of Salmonella typhimurium directs the translocation of Sip proteins into the host cell. Mol. Microbiol. 24:747-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collazo, C. M., and J. E. Galán. 1996. Requirement for exported proteins in secretion through the invasion-associated type III system of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 64:3524-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collazo, C. M., M. K. Zierler, and J. E. Galan. 1995. Functional analysis of the Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes invI and invJ and identification of a target of the protein secretion apparatus encoded in the inv locus. Mol. Microbiol. 15:25-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darwin, K. H., and V. L. Miller. 2000. The putative invasion protein chaperone SicA acts together with InvF to activate the expression of Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:949-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darwin, K. H., and V. L. Miller. 2001. Type III secretion chaperone-dependent regulation: activation of virulence genes by SicA and InvF in Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 20:1850-1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis, R. W., D. Botstein, and J. R. Roth. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics: a manual for genetic engineering. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 18.Deiwick, J., and M. Hensel. 1999. Regulation of virulence genes by environmental signals in Salmonella typhimurium. Electrophoresis 20:813-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deiwick, J., T. Nikolaus, S. Erdogan, and M. Hensel. 1999. Environmental regulation of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1759-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deiwick, J., T. Nikolaus, J. E. Shea, C. Gleeson, D. W. Holden, and M. Hensel. 1998. Mutations in Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI2) genes affecting transcription of SPI1 genes and resistance to antimicrobial agents. J. Bacteriol. 180:4775-4780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennis, P. P. 1974. Synthesis of individual ribosomal proteins in Escherichia coli B/r. J. Mol. Biol. 89:223-232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorman, C. J., S. Chatfield, C. F. Higgins, C. Hayward, and G. Dougan. 1989. Characterization of porin and ompR mutants of a virulent strain of Salmonella typhimurium: ompR mutants are attenuated in vivo. Infect. Immun. 57:2136-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eichelberg, K., and J. E. Galán. 1999. Differential regulation of Salmonella typhimurium type III secreted proteins by pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1)-encoded transcriptional activators InvF andhilA. Infect. Immun. 67:4099-4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ernst, R. K., D. M. Dombroski, and J. M. Merrick. 1990. Anaerobiosis, type 1 fimbriae, and growth phase are factors that affect invasion of HEp-2 cells by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 58:2014-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fahlen, T. F., N. Mathur, and B. D. Jones. 2000. Identification and characterization of mutants with increased expression of hilA, the invasion gene transcriptional activator of Salmonella typhimurium. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fahlen, T. F., R. W. Wilson, J. D. Boddicker, and B. D. Jones. 2001. Hha is a negative modulator of hilA transcription, the Salmonella typhimurium invasion gene transcriptional activator. J. Bacteriol. 183:6620-6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francis, C. L., T. A. Ryan, B. D. Jones, S. J. Smith, and S. Falkow. 1993. Ruffles induced by Salmonella and other stimuli direct macropinocytosis of bacteria. Nature 364:639-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu, Y., and J. E. Galán. 1998. Identification of a specific chaperone for SptP, a substrate of the centisome 63 type III secretion system of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 180:3393-3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galán, J. E., and R. Curtiss III. 1990. Expression of Salmonella typhimurium genes required for invasion is regulated by changes in DNA supercoiling. Infect. Immun. 58:1879-1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galán, J. E., and R. Curtiss III. 1989. Cloning and molecular characterization of genes whose products allow Salmonella typhimurium to penetrate tissue culture cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:6383-6387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallois, A., J. R. Klein, L. A. Allen, B. D. Jones, and W. M. Nauseef. 2001. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-encoded type III secretion system mediates exclusion of NADPH oxidase assembly from the phagosomal membrane. J. Immunol. 166:5741-5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galyov, E. E., M. W. Wood, R. Rosqvist, P. B. Mullan, P. R. Watson, S. Hedges, and T. S. Wallis. 1997. A secreted effector protein of Salmonella dublin is translocated into eukaryotic cells and mediates inflammation and fluid secretion in infected ileal mucosa. Mol. Microbiol. 25:903-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ginocchio, C., J. Pace, and J. E. Galan. 1992. Identification and molecular characterization of a Salmonella typhimurium gene involved in triggering the internalization of salmonellae into cultured epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5976-5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gottesman, S., and V. Stout. 1991. Regulation of capsular polysaccharide synthesis in Escherichia coli K12. Mol Microbiol. 5:1599-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grossman, A. D., W. E. Taylor, Z. F. Burton, R. R. Burgess, and C. A. Gross. 1985. Stringent response in Escherichia coli induces expression of heat shock proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 186:357-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, B. Raupach, D. Monack, S. Falkow, C. Gleeson, T. Kubo, and D. W. Holden. 1997. Functional analysis of ssaJ and the ssaK/U operon, 13 genes encoding components of the type III secretion apparatus of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. Mol. Microbiol. 24:155-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, S. R. Waterman, R. Mundy, T. Nikolaus, G. Banks, T. A. Vazquez, C. Gleeson, F. C. Fang, and D. W. Holden. 1998. Genes encoding putative effector proteins of the type III secretion system of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 are required for bacterial virulence and proliferation in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 30:163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hueck, C. J., M. J. Hantman, V. Bajaj, C. Johnston, C. A. Lee, and S. I. Miller. 1995. Salmonella typhimurium secreted invasion determinants are homologous to Shigella Ipa proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 18:479-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones, B. D., and S. Falkow. 1994. Identification and characterization of a Salmonella typhimurium oxygen-regulated gene required for bacterial internalization. Infect. Immun. 62:3745-3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaniga, K., J. C. Bossio, and J. E. Galan. 1994. The Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes invF and invG encode homologues of the AraC and PulD family of proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 13:555-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaniga, K., D. Trollinger, and J. E. Galán. 1995. Identification of two targets of the type III protein secretion system encoded by the inv and spa loci of Salmonella typhimurium that have homology to the Shigella IpaD and IpaA proteins. J. Bacteriol. 177:7078-7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein, J. R., and B. D. Jones. 2001. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-encoded proteins SseC and SseD are essential for virulence and are substrates of the type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 69:737-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee, A. K., C. S. Detweiler, and S. Falkow. 2000. OmpR regulates the two-component system SsrA-SsrB in Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. J. Bacteriol. 182:771-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee, C. A., and S. Falkow. 1990. The ability of Salmonella to enter mammalian cells is affected by bacterial growth state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4304-4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lostroh, C. P., V. Bajaj, and C. A. Lee. 2000. The cis requirements for transcriptional activation by HilA, a virulence determinant encoded on SPI-1. Mol. Microbiol. 37:300-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McBeth, K. J., and C. A. Lee. 1993. Prolonged inhibition of bacterial protein synthesis abolishes Salmonella invasion. Infect. Immun. 61:1544-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miao, E. A., J. A. Freeman, and S. I. Miller. 1999. Transcription of the SsrAB regulon is repressed by alkaline pH and is independent of PhoPQ and magnesium concentration. J. Bacteriol. 184:1493-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miao, E. A., and S. I. Miller. 2000. A conserved amino acid sequence directing intracellular type III secretion by Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7539-7544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller, W. G., J. H. Leveau, and S. E. Lindow. 2000. Improved gfp and inaZ broad-host-range promoter-probe vectors. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:1243-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mills, D. M., V. Bajaj, and C. A. Lee. 1995. A 40 kb chromosomal fragment encoding Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes is absent from the corresponding region of the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 15:749-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore, A. E., L. Sabachewsky, and H. W. Toolan. 1955. Culture characteristics of four permanent lines of human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 15:598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Penheiter, K. L., N. Mathur, D. Giles, T. Fahlen, and B. D. Jones. 1997. Non-invasive Salmonella typhimurium mutants are avirulent because of an inability to enter and destroy M cells of ileal Peyer's patches. Mol. Microbiol. 24:697-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfeifer, C. G., S. L. Marcus, M. O. Steele, L. A. Knodler, and B. B. Finlay. 1999. Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes are induced upon bacterial invasion into phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 67:5690-5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rakeman, J. L., H. R. Bonifield, and S. I. Miller. 1999. A HilA-independent pathway to Salmonella typhimurium invasion gene transcription. J. Bacteriol. 181:3096-3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodriguez, C. R., L. M. Schechter, and C. A. Lee. 2003. Detection and characterization of the S. typhimurium HilA protein. BMC Microbiol. 2:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salcedo, S. P., M. Noursadeghi, J. Cohen, and D. W. Holden. 2001. Intracellular replication of Salmonella typhimurium strains in specific subsets of splenic macrophages in vivo. Cell Microbiol. 3:587-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schechter, L. M., S. M. Damrauer, and C. A. Lee. 1999. Two AraC/XylS family members can independently counteract the effect of repressing sequences upstream of the hilA promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 32:629-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schechter, L. M., and C. A. Lee. 2001. AraC/XylS family members, HilC and HilD, directly bind and derepress the Salmonella typhimurium hilA promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1289-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shea, J. E., C. R. Beuzon, C. Gleeson, R. Mundy, and D. W. Holden. 1999. Influence of the Salmonella typhimurium pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system on bacterial growth in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 67:213-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shea, J. E., M. Hensel, C. Gleeson, and D. W. Holden. 1996. Identification of a virulence locus encoding a second type III secretion system in Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2593-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi, J., and D. P. Biek. 1995. A versatile low-copy-number cloning vector derived from plasmid F. Gene 164:55-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steele, M. O., J. H. Brumell, L. A. Knodler, S. Meresse, A. Lopez, and B. B. Finlay. 2002. The invasion-associated type III secretion system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is necessary for intracellular proliferation and vacuole biogenesis in epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 4:43-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takaya, A., M. Suzuki, H. Matsui, T. Tomoyasu, H. Sashinami, A. Nakane, and T. Yamamoto. 2003. Lon, a stress-induced ATP-dependent protease, is critically important for systemic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection of mice. Infect. Immun. 71:690-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takaya, A., T. Tomoyasu, A. Tokumitsu, M. Morioka, and T. Yamamoto. 2002. The ATP-dependent Lon protease of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium regulates invasion and expression of genes carried on Salmonella pathogenicity island 1. J. Bacteriol. 184:224-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Uchiya, K., M. A. Barbieri, K. Funato, A. H. Shah, P. D. Stahl, and E. A. Groisman. 1999. A Salmonella virulence protein that inhibits cellular trafficking. EMBO J. 18:3924-3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vazquez, T. A., Y. Xu, C. J. Jones, D. W. Holden, S. M. Lucia, M. C. Dinauer, P. Mastroeni, and F. C. Fang. 2000. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent evasion of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science 287:1655-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson, R. L., S. J. Libby, A. M. Freet, J. D. Boddicker, T. F. Fahlen, and B. D. Jones. 2001. Fis, a DNA nucleoid-associated protein, is involved in Salmonella typhimurium SPI-1 invasion gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 39:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wray, C., and W. J. Sojka. 1978. Experimental Salmonella typhimurium in calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 25:139-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou, D., and J. Galan. 2001. Salmonella entry into host cells: the work in concert of type III secreted effector proteins. Microbes Infect. 3:1293-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]