Abstract

Objective

Little is known about which attributes the patients need when they wish to maximise their capability to partner safely in healthcare. We aimed to identify these attributes from the perspective of key opinion leaders.

Design

Delphi study involving indirect group interaction through a structured two-round survey.

Setting

International electronic survey.

Participants

11 (65%) of the 17 invited internationally recognised experts on patient safety completed the study.

Outcome measures

50 patient attributes were rated by the Delphi panel for their ability to contribute maximally to safe health care.

Results

The panellists agreed that 13 attributes are important for patients who want to maximise the role of safe partners. These domains relate to: autonomy, awareness, conscientiousness, knowledge, rationality, responsiveness and vigilance; for example, important attributes of autonomy include the ability to speak up, freedom to act and ability to act independently. Spanning seven domains, the attributes emphasise intellectual attributes and, to a lesser extent, moral attributes.

Conclusions

Whereas current safety discourses emphasise attributes of professionals, this study identified the patient attributes which key opinion leaders believe can maximise the capability of patients to partner safely in healthcare. Further research is needed that asks patients about the attributes they believe are most important.

Keywords: Medical Ethics

Article summary.

Article focus

This paper aimed to identify, from the perspective of key opinion leaders, the personal attributes that patients need when they wish to maximise their capability to partner safely in healthcare.

Key messages

A Delphi exercise involving 11 international experts on patient safety identified 10 intellectual and three moral attributes as being important for patients wanting to maximise their ability to be safe healthcare partners.

The intellectual attributes are in the domains of autonomy, awareness, conscientiousness, responsiveness and vigilance; the moral attributes constitute domains of conscientiousness and vigilance.

Important attributes of patient autonomy include the ability to speak up and act independently, as well as the freedom to act.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Going beyond safety discourses that emphasise attributes of safe health professionals, this study elicits perspectives of key opinion leaders on attributes that enable patients to maximise their capability to serve as safe healthcare partners.

However, this study was small, individual attributes can be interpreted in different ways, and there is a need to ask patients themselves about the attributes that they need in order to partner most safely.

Introduction

Patient safety policies and discourses promote safety initiatives that enable patients (and their families) to be active partners in healthcare,1 for example, by detecting and reporting possible safety events.2 This kind of patient involvement respects and empowers patients as people—rather than as dehumanised by products of the ‘medical gaze’3—and may improve the quality and outcomes of healthcare.1 Research has explored factors that influence the willingness4 5 and motivation6 of patients to participate in safety initiatives. Little is known, however, about which personal attributes of patients are important when they wish to maximise their safe participation in healthcare.

Long et al7 identified the attributes and qualities of safe health professionals within complex and imperfect health systems. Davis et al8 earlier identified patient-related and illness-related factors associated with patient involvement in health safety.2 Coulter and Ellins1 had highlighted the importance of health literacy to patients obtaining and understanding basic health information. More widely, however, safety experts have yet to identify and agree explicitly on key personal attributes of safe patients. This lack of agreement persists despite variation in the capacity of patients to act for safety and in the levels of support they need.9

We are not assuming here that patients should have certain attributes. Rather, we are suggesting that such attributes can be important resources when patients wish to participate actively as safe partners in healthcare. This perspective draws on Sen's10 theory of human capabilities. His capability approach is consistent with the notion that patients’ personal attributes are resources, which can define their capabilities for safe functioning in medicine.11 These capabilities signify feasible opportunities for patients to be safe and act safely. They permit patients to be free agents of change and live the kind of lives they find valuable. However, Sen's capability approach emphasises the capabilities (ends) themselves, whereas we focus on identifying (and weighting) the attributes necessary for capability. Thus, the social environment, on which conversion of some resources for capability may depend, sits outside the scope of our study, as does the ability to assess the safety that patients have achieved or could achieve.

Judged in terms of opportunity, the expression ‘safe partner’ may imply that the patient does not err,12 for example, by not forgetting to take medication,13 independently of the issue of moral responsibility.14 Alternatively, it may imply that the patient maximises the safety of healthcare by doing ‘good’ (in the philosophical sense of doing what is important or valuable). For example, the patient might report an error to their health provider; this distinction resembles the difference between non-maleficence and beneficence.

For our purpose, the first meaning is timid and too restrictive. It is also subsumed within the second meaning that emphasises the minimum attributes that patients need in order to maximise their capability to partner safely. This perspective resembles the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Health Care Organizations’ focus on accreditation standards that are maximally achievable.15 Thus, we aimed specifically to identify the most important attributes that patients need when they wish to maximise their capability to partner safely in healthcare. Rather than reduce the spotlight on the clinician, this approach widens the spotlight to encompass patients as coproducers of safe care according to their capacity and willingness to play that role.

Method

We conducted a Delphi study approved by the University of Auckland Ethics Committee (Ref. 8126, 8 May 2012). The Delphi method elicits expert judgements through indirect group interaction. It is suited here for building formal consensus between participants in the absence of strong research evidence as to the most important attributes defining patients as safe healthcare partners. Our exercise involved geographically isolated experts.

Identified through the authors’ extensive work experience and professional networks, these individuals are recognised internationally as having and applying in-depth, specialised knowledge and skills in the area of patient safety. We involved these experts in a structured, on-line, two-round survey in late 2012.

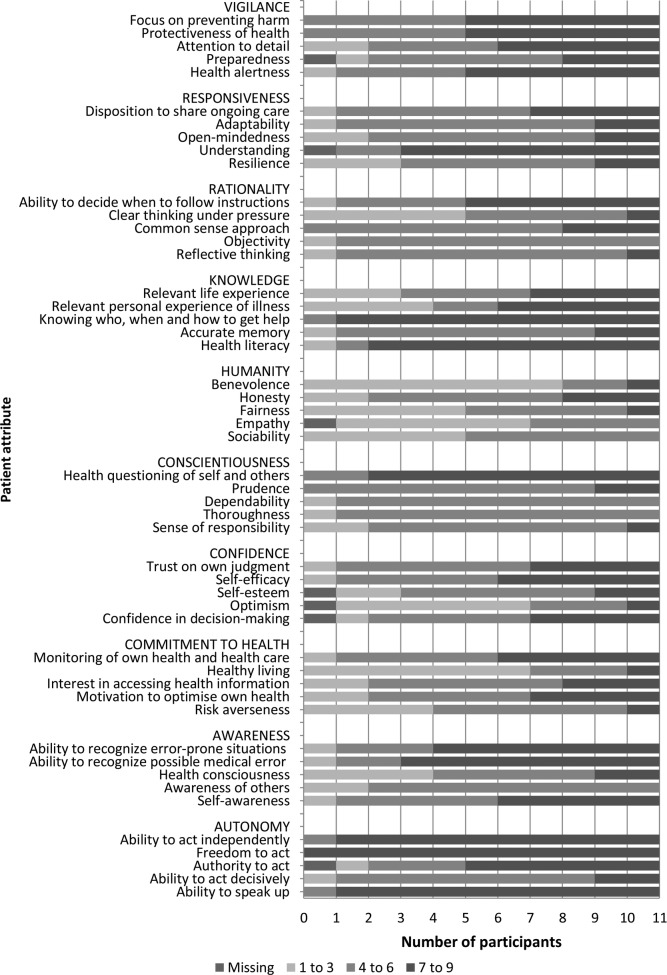

Physicians have been reported to typify individual patients as ‘good’ or not on the basis of their adherence to unwritten rules of conduct.16 However, from the literature spanning healthcare and philosophy—specifically in areas including patient safety, patient participation, and ethical theory and principles such as personhood—we identified 10 preliminary domains of five patient attributes. Figure 1 shows these domains and attributes. Each participant was asked to rate each of the 50 attributes, by domain, on a 9-point Likert scale of importance ranging from 1, clearly unimportant, to 9, clearly important, and was given at the end of round 1 an opportunity to comment on the survey questionnaire as a whole and suggest changes to the attributes assessed.

Figure 1.

Distribution of expert ratings of important patient attributes.

In round 2, the participants were sent a questionnaire that revised the wording of some attributes on the basis of feedback received from round 1; but that retained the same thematic structure. They also received their own ratings of each first round attribute in relation to the group distribution. In search of group consensus, this statistical feedback was intended to inform the second round ratings of individual attributes, and to reduce ‘disagreement’, as defined by a median rating in the top tertile (7–9) and two or more panellists rating the attribute in the bottom tertile (1–3). Attributes with a median rating of 7–9 on the scale of importance, without disagreement, make up the study's final list of patient attributes. The amount and direction of change occurring in the ratings between the rounds was assessed by summarising the differences between median ratings and absolute differences between median ratings.

Results

Seventeen safety experts were invited to participate in the study. Thirteen responded, of whom 12 agreed to take part and completed round 1. Table 1 shows that 11 (65%) also completed round 2. Online supplementary appendix 1 lists these participants and their academic position. All of them were aged at least 40 years and nine were men. Eight were residing in the Northern hemisphere. Panellists reported multiple forms of involvement in safety-related work, including most commonly academic employment and clinical practice.

Table 1.

Attributes of round 2 Delphi panellists

| Sex | |

|---|---|

| Female | 9 |

| Male | 2 |

| Age group | |

| 40–49 | 2 |

| 50–59 | 7 |

| 60 or older | 2 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 11 |

| Country of residence | |

| Australia | 1 |

| New Zealand | 2 |

| UK | 4 |

| Europe | 1 |

| USA | 3 |

| Safety-related work | |

| Academic | 10 |

| Clinical practice | 5 |

| Consumer representation | 1 |

| Health management | 2 |

| Health policy | 2 |

For each patient attribute, figure 1 shows the ratings distribution, by tertile (1–3, 4–6 and 7–9), of the 11 round 2 participants. Table 2 lists the 13 patient attributes which the panel agreed are important in enabling patients to contribute maximally to safe healthcare. These attributes constitute 7 of the 10 domains of attributes included in the round 2 questionnaire. The highest rated are the attributes relating to autonomy, in particular the ‘Ability to speak up’. The next rated highest are the ‘Freedom to act’ and ‘Ability to act independently’, which similarly relate to autonomy, and ‘Knowing who, when and how to call for help’. Other important domains of safe patient attributes relate to vigilance and awareness of safety issues, respectively. The table reports no attributes from three domains: commitment to health, confidence and humanity. It shows that between rounds the median ratings increased for seven important attributes and decreased for six. The amount of change between rounds in median ratings is generally small; the greatest difference was a decline in the round 2 median rating of the importance of a patient having the ability to decide when to follow instructions.

Table 2.

Ratings of the importance of patient attributes for maximal involvement in safe healthcare

| Domain | Attribute | Round 2 |

Difference between medians of rounds 1 and 2 |

Absolute difference between medians of rounds 2 and 1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | Mean | Min* | Max* | Mean | Min | Max | ||

| Autonomy | Ability to speak up | 9 | 3 | −0.2 | −3 | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 3 |

| Freedom to act | 8 | 1 | 0.8 | −1 | 4 | 1.0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Ability to act independently | 8 | 4 | 1.2 | −1 | 5 | 1.4 | 0 | 5 | |

| Awareness | Ability to recognise possible medical error | 7 | 7 | −0.9 | −3 | 2 | 1.2 | 0 | 3 |

| Ability to recognise error-prone situations | 7 | 8 | −0.2 | −3 | 2 | 1.1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Conscientiousness | Questioning of self and others | 7 | 5 | 0.8 | −2 | 5 | 1.4 | 0 | 5 |

| Knowledge | Health literacy | 7 | 8 | −0.2 | −8 | 3 | 1.5 | 0 | 8 |

| Knowing who, when and how to call for help | 8 | 2 | 0.3 | −1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 2 | |

| Rationality | Ability to decide when to follow instructions | 7 | 8 | −2.2 | −6 | 0 | 2.2 | 0 | 6 |

| Responsiveness | Understanding | 7 | 4 | −1.6 | −4 | 0 | 1.6 | 0 | 4 |

| Vigilance | Health alertness | 7 | 6 | 0.4 | −2 | 5 | 0.9 | 0 | 5 |

| Protectiveness of health | 7 | 5 | 1.4 | −1 | 5 | 1.5 | 0 | 5 | |

| Focus on preventing harm | 7 | 4 | 1.0 | −1 | 3 | 1.2 | 0 | 3 | |

*Max, maximum value; Min, minimum value.

Discussion

Safety discourses in medicine emphasise personal attributes of health professionals. However, patients vary in their capability and willingness for active involvement in safety. Therefore, this study aimed to determine, from the perspective of key opinion leaders, attributes that patients need when they wish to maximise their capability to partner safely in healthcare. We have reported 13 such attributes agreed on by our panel.

This study also emphasised the importance of the autonomy of the patient to speak up and choose freely to collaborate or not for safe healthcare. These attributes and others describing awareness, knowledge, rationality and responsiveness appear to be cognitive or intellectual. In contrast, important attributes relating to conscientiousness and vigilance seem better described as moral attributes, or attributes of character, despite the relatedness of these two broad domains of patient attributes. One reason for the importance of the intellectual attributes may be that their meaning and importance are less subjective and less contingent on the particular situation presenting in healthcare.

Does this study ask too much of patients? We believe ‘no’ for two reasons. First, in the tradition of the philosopher David Hume, the capability approach on which we draw is descriptive rather than normative. It does not prescribe the requirements of all patients. Respectful of patients, it merely indicates attributes that support their willing capability to partner safely. Second, we have focused on personal attributes that can enable patients to do the right thing, rather than necessarily do the right thing for the right reasons. For example, we have listed honesty as a potential attribute without distinguishing between truth-telling, as a behaviour, and authenticity as a virtuous disposition of character. Despite a small amount of literature on patient virtues,17–20 a focus on virtue was beyond the scope of this study.

Strengths and limitations

This study respects patients as people, whose personal attributes warrant as much consideration as those of health professionals, for their capacity to maximise safety in healthcare. In the absence of research evidence for the importance of different patient attributes, we have conducted a Delphi study. It allowed systematic, indirect interaction between international experts with knowledge of patient safety. All the round 2 ratings received equal consideration in this exercise.

Nevertheless, this small study has limitations. In the context of experts’ subjective judgements of the importance of individual attributes, one panellist expressed concern that many attributes can be interpreted in different ways, and their importance depends on the context. However, the same criticism can be levelled at common attempts, within philosophy, to define virtues of character; for example, humility is typically considered a virtue even though Aristotle considered it a vice. Therefore, the key issue, we suggest, is not whether interpretations vary owing to their abstractness (they frequently do vary) but whether this variation matters. From our perspective, the variation is unimportant because each attribute contains an implicit clause of ceteris paribus: all other things being equal, humility is generally now seen to be desirable and its importance can be assessed alongside that of other human attributes.

Among the other limitations are some attributes, such as ‘ability to speak up’, which could also be grouped into different domains. In turn, the domains themselves may overlap. However from a classical perspective, domains are discrete entities, and a ‘cognitive approach’ recognises their tendency to be fuzzy at their boundaries and inconsistent in their constitution. They merely comprise the best-fitting attributes, called prototypes.

The concept of ‘experts’ has also been contested when restricted to professionals and applied to patients.21 Our Delphi panel was a small select group. Its opinions may be biased, but this concern limits all such exercises. Moreover, although sound inquiry requires self--reflection, the extent to which bias is problematic hinges on ‘assumptions about objective method’.22 The opinions of the panel are enabling, not least because they command respect, coming from experts who have experience in applying knowledge of human factors to the design and management of safe healthcare systems.

That said, the study lacked a concerted lay voice, although experience as a mental health service user and activist has informed the contributions of one panellist. Her feedback and that of others on the round 1 questionnaire guided changes to, and ratings of, the round 2 questionnaire. There is a lack of literature on the attributes of safe patients with which to compare our findings. However, these findings are consistent with the growing interest in goods internal to the practice of medicine, including attributes of safe practitioners.7

Other limitations of the study include the use of formal consensus building to manage limits to expert knowledge. This approach is susceptible to manipulation, but movement in the median ratings between rounds was generally small and not saliently upwards. The Delphi process thus apparently enabled panellists to share differences and similarities in their thinking, without feeling group pressure to conform in round 2 to the round 1 ratings fed back to them.23 Note, however, that for round 2, some attributes were slightly reworded, the context and purpose of the study were clarified and the term ‘safe partner’ was explicitly defined.

The panellists’ anonymity to each other in their ratings facilitated their freedom of expression but could have reduced their sense of group accountability and denied them benefits of direct group interaction. The two rounds could also have sapped panellist motivation, since one panellist did not complete the second round. However, the rounds were short and 3 months apart. We accept that the attributes rated are not necessarily stable within individuals and across situations, but consensus on important attributes spans millennia and cultures.24

We have entered a contentious and underexplored area of research in which difficulties will continue to emerge. There is clearly a need for further research. The next step is to ask patients themselves about the attributes that may enable patients to maximise their capability to partner safely in healthcare. Also needed are studies that can support understanding of the findings that describe important patient attributes, as well as those that assess the readiness and willingness of professionals and patients to cultivate these attributes at all levels of healthcare. Our findings are preliminary, but, as a starting resource, we believe that they indicate patient attributes whose further investigation and development may help to maximise the capability of patients to partner safely in healthcare.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SB conceived of the project and led its design and implementation. RD, KC and SD contributed to the study design and the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The round 2 Delphi questionnaire is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Coulter A, Ellins J. Patient-focused interventions: a review of the evidence. London: Health Foundation, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality The role of the patient in safety. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foucault M. The birth of the clinic: an archaeology of medical perception. New York: Vintage, 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis R, Sevdalis N, Rosamond J, et al. An examination of opportunities for the active patient in improving patient safety. J Patient Saf 2012;8:36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis R, Sevdalis N, Vincent C. Patient involvement in patient safety: how willing are patients to participate? Qual Saf Health Care 2011;20:108–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwappach D. Engaging patients as vigilant partners in safety: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev 2010;67:119–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long S, Akora S, Moorthy K, et al. Qualities and attributes of a safe practitioner: identification of safety skills in healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care 2011;20:483–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis R, Jacklin R, Sevdalis N, et al. Patient involvement in patient safety: what factors influence patient participation and engagement. Health Expect 2007;10:259–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Entwistle V, Mello M, Brennan T. Advising patients about patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2005;31:483–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sen A. Inequality reexamined. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muir Gray J. The resourceful patient. Oxford: eRosetta Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buetow S, Elwyn G. Patient safety and patient error. Lancet 2007;369:158–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buetow S, Kiata-Holland L, Liew T, et al. Patient error: a preliminary taxonomy. Ann Fam Med 2009;7:223–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buetow S, Elwyn G. Are patients morally responsible for their errors? J Med Ethics 2006;32:260–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Organizations (JCAHO) Welcome to the Joint Commission Homepage. Oakbrook Terrace, IL, 2002. http://www.jcaho.org/ (accessed 7 Mar 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokes T, Dixon-Woods M, Williams S. Breaking the ceremonial order: patients’ and doctors’ accounts of removal from a general practitioner's list. Sociol Health Illn 2006;28:611–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell A, Swift T. What does it mean to be a virtuous patient? Virtue from the patient's perspective. Scot J Health Care Chaplain 2002;5:29–35 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shelp E. Courage: a neglected virtue in the patient-physician relationship. Soc Sci Med 1984;18:351–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebacqzk K. The virtuous patient. In: Shelp E. ed Virtue and medicine. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1985:275–88 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waring D. The virtuous patient: psychotherapy and the cultivation of character. Philos Psychiatr Psychol 2012;19:25–35 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prior L. Belief, knowledge and expertise: the emergence of the lay expert in medical sociology. Sociol Health Illn 2003;25:41–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwandt T. Dictionary of qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woudenberg F. An evaluation of Delphi. Technol Forecast Soc 1991;40:131–50 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson C, Seligman M. eds Character strengths and virtues. A handbook and classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.