Abstract

Background

We used universal screening to determine prevalence rates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC), Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) in 9,256 women enrolling into a contraceptive study.

Methods

2We offered screening using nucleic acid amplification or culture to all participants enrolling into the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Demographic characteristics were collected through staff administered questionnaires. Univariate and multivariable analyses were performed to assess the risk of STI at baseline and to compare risk profiles of CT and TV.

Results

Results were available for 8347 consenting women with satisfactory results; 656 (7.9%) tested positive for one or more infections. Approximately one third of participants were greater than 26 years of age, and half identified as African American. There were 35 cases of GC for a prevalence of 0.4% (95% CI: 0.3, 0.6), 260 cases of CT for a prevalence of 3.1% (95% CI: 2.8, 3.5), and 410 cases of TV for a prevalence of 4.9% (95% CI: 4.4, 5.4). Black women were more likely to test positive (OR: 3.95, 95% CI: 3.08, 5.06) compared to white women and accounted for 81.3% of cases. TV was more prevalent in black women (8.9%) as compared to white women (0.9%). Older age was a risk factor for TV, while younger age was associated with CT. Of the 656 positive cases, 106 (16%) were diagnosed in women over 25 years of age, falling outside traditional screening guidelines.

Conclusion

We found GC, CT, and TV to be more prevalent than current national statistics, with TV being the most prevalent. Current screening recommendations would have missed 16% of infected women.

Keywords: Sexually transmitted infection, prevalence, screening

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) carry significant and important implications for female reproductive health including pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility. [1–5] Age, race, history of STI, early age of first intercourse, number of life-time sexual partners, and multiple sexual partners have been repeatedly shown to be associated with STIs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends routine CT screening for all sexually active females younger than 26 years of age and risk-based screening for women 26 years or older.[6]

Screening recommendations generally arise from disease prevalence data and are often tailored to patients with known risk factors. Accurate estimation of disease prevalence is difficult. Traditionally, statistics regarding prevalence are derived from large population studies such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) or notifiable disease surveillance systems. These sources provide valuable information on an on-going basis; most notably they provide a generalizable assessment of disease prevalence. However, these sources can be dependent on positive test reporting by clinicians and often draw from sentinel sites such as STI clinics, family planning clinics, and the National Job Training Program.

Accurate estimates of disease prevalence are difficult for a number of reasons. Screening modalities and protocols may change over time making it difficult to determine whether changes in prevalence are attributable to an actual change in infection rates or a change in screening indications, testing method, and reporting. For example, Job Corps entrants from 2003 to 2007 were screened for Chlamydia trachomatis using different tests.[7] Secondly, many infections are asymptomatic and thus adherence to screening guidelines highly influences the number of positive cases diagnosed. The CDC estimates that screening occurs in less than half of those who should be screened. [8–11] Lastly, the existence of multiple diagnostic tests for each infection further complicates the issue, as each of these tests carries its own sensitivity and specificity. For example, most clinicians still rely on traditional saline microscopy for trichomoniasis, which has been shown to have a sensitivity of approximately 60%, rather than the more modern and sensitive (95%) nucleic acid amplification or culture testing modalities. 12–14]

Positive cases reported to the CDC have allowed for estimation of disease prevalence. In 2010, more than 300,000 cases of Neisseria gonorrhea (GC) were reported for a rate of 100.8 per 100,000 people (0.10%). There are more than 1.3 million cases of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) in the U.S. for a rate of 426 per 100,000 people (0.43%).[8, 15] Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) prevalence is more difficult to estimate. Trichomoniasis is not a reportable infection, there are no screening guidelines, and the most commonly used diagnostic technique (microscopic evaluation) is inadequate. Despite these difficulties, the CDC has estimated that there are 2.3 million cases annually in U.S., and data from the NHANES found an overall prevalence of 3.1%. [14]

In an effort to supplement prevalence data from large population-based, cross-sectional studies and surveillance initiatives, we implemented a universal screening protocol using highly sensitive and specific nucleic acid amplification tests for GC and CT and culture for TV in an urban population seeking no-cost contraception. We estimated the baseline prevalences of GC, CT, and TV in women at baseline enrollment and compared these rates to the national rates reported by the CDC.

Materials and Methods

This is an analysis of data collected from participants at the time of enrollment into the Contraceptive CHOICE Project (CHOICE). All study related procedures were approved by Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office prior to participant recruitment. CHOICE is an observational cohort study of 9,256 women residing in the St. Louis area. The project was designed to promote the use of the most effective contraceptive methods and reduce unintended pregnancy in the region. The methods of CHOICE have been previously described;[16] we will provide a brief summary here. Participants were recruited through word-of-mouth, healthcare provider referrals, and at community family planning, abortion clinics, and university-based medical clinics. Women were eligible for CHOICE if they were 14–45 years old, not currently using a method of contraception or willing to try a new reversible contraceptive method, did not desire pregnancy for one year, did not have a hysterectomy or tubal ligation, and were currently sexually active with a male partner or planned to be sexually active in the next 6 months. All participants completed an in-person enrollment session that included standardized contraceptive counseling, informed written consent, a staff-administered baseline questionnaire, and STI screening. The baseline questionnaire included questions regarding demographic characteristics, reproductive health and contraceptive history, sexual behaviors with current partners, drug and alcohol use, and history of STI.

During enrollment, women completed self-collected vaginal swabs to test for CT, GC and TV infections. DNA strand displacement analysis using BDProbeTec ET instrument (Becton Dickson, Sparks, MD) was used to detect CT and GC infections. TV was detected using the InPouch TV culture (BioMed Diagnostics, White City, OR).

We examined the demographic and behavioral characteristics known to be associated with STIs and compared women who tested positive for any STI compared to those who tested negative for all infections. We used the χ2 test for comparisons of categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. We created a multivariable model using logistic regression to estimate the odds of any infection. We also created two multivariable models to estimate the odds of CT infection only and the odds of TV infection only. Independent predictors of CT infection and TV infection that were statistically significant in univariate analysis were included in the final multivariable models. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS Software (v.9.2., SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

From Aug 2007 through September 2011, 9,256 women enrolled into the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and reproductive characteristics of the cohort. Greater than one third of the cohort (39%) was 26 years or older and half (51%) identified themselves as African American or black. Nearly two thirds (65%) of the cohort reported at least some college or vocational education, and the majority (61%) were single or never married. Low socio-economic status (SES) was common (58%) and was defined as those women who reported having trouble paying for housing, transportation, food, or healthcare, as well as those receiving public assistance such as food stamps, welfare, or unemployment.

Table 1.

Demographic and reproductive characteristics of women who tested positive compared to negative for ≥1 sexually transmitted infection at enrollment.

| Overall (n=8,347) | STI-Positive (n=656) | STI-Negative (n=7,691) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 14–17 | 411 | 4.9 | 29 | 4.4 | 382 | 5.0 | |

| 18–20 | 1989 | 23.8 | 215 | 32.8 | 1774 | 23.1 | |

| 21–25 | 2627 | 31.5 | 191 | 29.1 | 2436 | 31.7 | |

| 26–35 | 2740 | 32.8 | 192 | 29.3 | 2548 | 33.1 | |

| 36–45 | 580 | 7.0 | 29 | 4.4 | 551 | 7.2 | |

|

| |||||||

| Race | <0.001 | ||||||

| Black | 4210 | 49.3 | 533 | 82.3 | 3587 | 46.6 | |

| White | 3586 | 43.0 | 92 | 14.0 | 3494 | 45.4 | |

| Other | 640 | 7.7 | 31 | 4.7 | 609 | 8.0 | |

|

| |||||||

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never married | 5088 | 61.0 | 496 | 75.6 | 4592 | 59.8 | |

| Partnered but not married | 1704 | 20.4 | 107 | 16.3 | 1597 | 20.8 | |

| Married | 1006 | 12.1 | 27 | 4.1 | 979 | 12.7 | |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 543 | 6.5 | 26 | 4.0 | 517 | 6.7 | |

|

| |||||||

| Education | <0.001 | ||||||

| High school or less | 2767 | 33.2 | 310 | 47.3 | 2457 | 32.0 | |

| Some college | 3590 | 43.0 | 288 | 43.9 | 3302 | 43.0 | |

| College or graduate degree | 1987 | 23.8 | 58 | 8.8 | 1929 | 25.0 | |

|

| |||||||

| Insurance | <0.001 | ||||||

| None | 3477 | 41.9 | 322 | 51.1 | 3145 | 41.2 | |

| Public | 1159 | 14.0 | 139 | 21.4 | 3476 | 13.3 | |

| Private | 3655 | 44.1 | 179 | 27.5 | 1020 | 45.5 | |

|

| |||||||

| Low socioeconomic statusa | 4778 | 57.2 | 479 | 73.0 | 4299 | 55.9 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Parity | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 4007 | 48.0 | 251 | 38.3 | 3756 | 48.8 | |

| 1 | 2050 | 24.5 | 203 | 31.0 | 1847 | 24.0 | |

| 2 | 1424 | 17.1 | 108 | 16.4 | 1316 | 17.1 | |

| 3 or more | 866 | 10.4 | 94 | 14.3 | 772 | 10.0 | |

|

| |||||||

| History of unintended pregnancy | 5208 | 62.5 | 491 | 75.1 | 4717 | 61.4 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Age at first sex (years) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 13 or less | 604 | 7.3 | 71 | 10.8 | 533 | 7.0 | |

| 14–15 | 2315 | 28.1 | 210 | 32.1 | 2105 | 27.8 | |

| 16–17 | 3152 | 38.3 | 252 | 38.5 | 2900 | 38.3 | |

| 18 or older | 2161 | 26.3 | 122 | 18.6 | 2039 | 26.9 | |

|

| |||||||

| Concurrent partners in past 30 days | 469 | 5.6 | 84 | 12.8 | 385 | 5.0 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Lifetime sexual partners | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1 | 736 | 9.0 | 25 | 3.9 | 711 | 9.4 | |

| 2–9 | 4947 | 60.4 | 422 | 65.1 | 4525 | 60.0 | |

| 10–19 | 1629 | 19.9 | 131 | 20.2 | 1498 | 19.9 | |

| 20–49 | 755 | 9.2 | 55 | 8.5 | 700 | 9.3 | |

| 50 or more | 121 | 1.5 | 15 | 2.3 | 106 | 1.4 | |

|

| |||||||

| History of sexually transmitted infectionb | 2081 | 24.9 | 244 | 37.2 | 1837 | 23.9 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Douche during the past 30 days | 809 | 9.7 | 97 | 15.0 | 712 | 9.3 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| History of drug use | 1630 | 19.5 | 176 | 26.8 | 1454 | 18.9 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Met CDC age-based screening criteriac | 5027 | 60.2 | 435 | 66.3 | 4592 | 59.7 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Met CDC risk-based screening criteriad | 1050 | 12.6 | 103 | 15.7 | 947 | 12.3 | 0.012 |

Current receipt of food stamps, WIC, welfare or unemployment or has trouble paying for transportation, housing, health or medical care or food

Self-reported history of chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis or HIV

≤25 years at time of screen

≥26 years at time of screen and reports concurrent partners or history of STI or current vaginal discharge

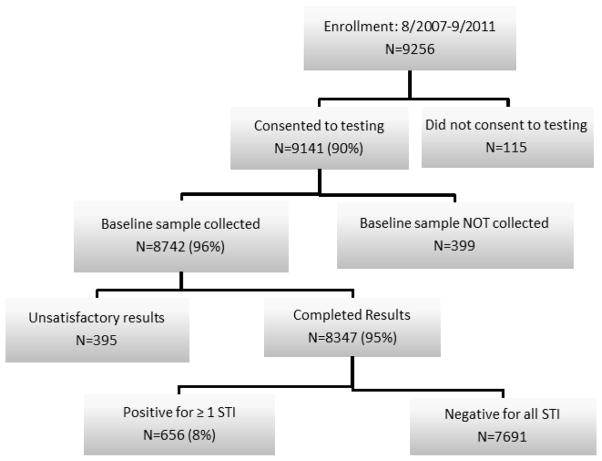

Of the 9,256 participants, results were available for 8,347(90%; Figure 1). The remaining 909 include participants with incomplete results or who declined testing. There were 656 (7.9%) women in the cohort who tested positive for one or more STI. Of the positive screens, there were 35 cases of GC for a prevalence of 0.4% (95% CI: 0.3, 0.6); 260 cases of CT, for a prevalence of 3.1% (95% CI: 2.8, 3.5); and 410 cases of TV, for a prevalence of 4.9% (95% CI: 4.4, 5.4).

Figure 1.

STI screening rates and results using a universal screening protocol

Demographic differences between those testing positive for one or more STI and those testing negative for all STIs are presented in table 2. Of note, the STI positive group was younger with a mean age of 24.2 years, compared to participants testing negative (mean age 25.3 years; p < 0.001). Black women were disproportionately represented in the group testing positive for one or more STI (81%). Those testing positive were also more likely to have never been married (76% vs. 60%, p<0.001), and to be of low SES (73% vs. 56%, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Predictors of positive STI screen at enrollment, and of prevalent C. trachomatis and T. vaginalis.

| ≥1 STIc (N=8,059) | C. trachomatisd (N=8,165) | T. vaginalise (N=8,059) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Characteristic | ORadj | 95% CI | ORadj 95% CI | ORadj | 95% CI | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 14–17 | 1.0 | 0.5, 1.9 | 6.2 | 1.6, 23.6 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.8 |

| 18–20 | 1.7 | 1.1, 2.8 | 10.4 | 3.1, 35.1 | 0.7 | 0.4, 1.3 |

| 21–25 | 1.4 | 0.9, 2.2 | 5.7 | 1.7, 18.9 | 0.9 | 0.6, 1.5 |

| 26–35 | 1.4 | 0.9, 2.1 | 2.7 | 0.8, 8.8 | 1.2 | 0.7, 1.8 |

| 36–45 | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 4.0 | 3.1, 5.1 | 2.2 | 1.6, 3.1 | 6.8 | 4.6, 10.0 |

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

| Other | 1.6 | 1.0, 2.5 | 0.9 | 0.5, 1.7 | 2.5 | 1.4, 4.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married | 2.7 | 1.8, 4.1 | 2.0 | 0.9, 4.2 | 3.4 | 2.0, 5.9 |

| Partnered but not married | 1.7 | 1.1, 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.7, 3.4 | 1.9 | 1.0, 3.4 |

| Married | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 1.5 | 0.9, 2.8 | 2.6 | 1.0, 6.9 | 1.7 | 0.8, 3.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less | 2.0 | 1.4, 2.9 | 1.8 | 1.0, 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.4, 3.3 |

| Some college | 1.5 | 1.1, 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.7, 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.0, 2.3 |

| College or graduate degree | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

|

| ||||||

| Insurance | ||||||

| None | 1.2 | 0.9, 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.9, 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.0, 1.7 |

| Public | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.8, 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.9, 1.7 |

| Private | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

|

| ||||||

| Low socioeconomic statusa | 1.2 | 0.9, 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.9, 1.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Parity | ||||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 0.8, 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.5 |

| 1 | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

| 2 | 0.9 | 0.7, 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.4, 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.7, 1.3 |

| 3 or more | 1.3 | 0.9, 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.6, 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.8, 1.7 |

|

| ||||||

| History of unintended pregnancy | 1.3 | 1.0, 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.2, 2.3 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age at first sex (years) | ||||||

| 13 or less | 1.2 | 0.9, 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.6, 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.9, 1.9 |

| 14–15 | 1.0 | 0.9, 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.8, 1.3 |

| 16–17 | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

| 18 or older | 1.1 | 0.9, 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.7, 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Concurrent partners in past 30 days | 2.1 | 1.6, 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.3, 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.4, 2.8 |

|

| ||||||

| Lifetime sexual partners | ||||||

| 1 | 0.7 | 0.4, 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.3, 1.1 | ||

| 2–9 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| 10–19 | 1.0 | 0.8, 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7, 1.2 | ||

| 20–49 | 0.9 | 0.6, 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.5, 1.1 | ||

| 50 or more | 1.5 | 0.8, 2.8 | 2.3 | 1.2, 4.3 | ||

|

| ||||||

| History of sexually transmitted infectionb | 1.0 | 0.8, 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.8, 1.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Douche during the past 30 days | 1.1 | 0.9, 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9, 1.7 | ||

|

| ||||||

| History of drug use | 1.4 | 1.1, 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.3, 2.2 | ||

Current receipt of food stamps, WIC, welfare or unemployment or has trouble paying for transportation, housing, health or medical care or food

Self-reported history of chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis or HIV

Model adjusted for all variables included in the table. 288 observations omitted due to missing values.

Model adjusted for age, race, marital status, education, insurance, low socioeconomic status, parity, age at first sex, concurrent sexual partners, and history of sexually transmitted infection. 182 observations omitted due to missing values.

Model adjusted for all variables included in the table. 288 observations omitted due to missing values.

ORadj = adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval

Multivariable analysis (Table 2), which included all factors found to be significant in the univariate model, identified age 18–21 years to be associated with a nearly 2-fold increased risk (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.2, 3.0) of any prevalent infection. Also significant were black race (OR: 4.0; 95% CI: 3.1, 5.1), never having been married (OR: 2.7; 95%CI: 1.8, 4.1), being partnered but not married (OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.7), and having less than or equal to a high-school education (OR: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.4, 2.8).

We looked specifically at the 656 women testing positive at baseline and evaluated whether they would have been screened under traditional age-based and risk-profile screening recommendations. Of the 656 positive screens, 188 (29%) were 26 years or older and outside of the current age-based recommendation for annual screening. Of these 188 women, only 22 (12%) reported having more than one current partner, and 75 (40%) reported a history of GC, CT, syphilis, or HIV. Among the women who tested positive, we identified 106 (16%) who were 26 years or older, reported no STI history, did not have multiple sexual partners, did not report vaginal symptoms, and as a result, would not have been screened under the CDC guidelines.

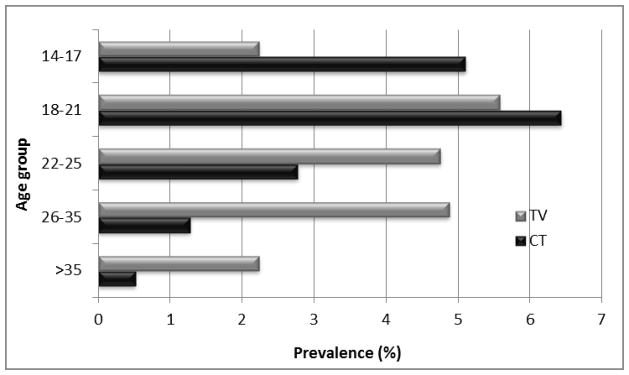

Demographic and reproductive characteristics were also compared between those testing positive for CT (n=260) and those testing positive for TV (n=410). GC was not included in this analysis because of the small number of positive cases. Younger women were more likely to test positive for CT. However, the distribution of TV prevalence was shifted toward older women. TV became more prevalent than CT beginning with the age 22–25 year age group, but is most dramatically noted in the women older than 35 years (Figure 2). Prevalence by race was also different. CT prevalence in black participants was higher than in white women (4.6% vs. 1.7%). A more dramatic difference was seen in TV prevalence rates by race with black women having a TV prevalence of 8.7% compared to 0.9% in white women.

Figure 2.

Age distribution of CT and TV infection prevalence

Multivariable analysis confirmed these findings (Table 2). Younger age, both 14–17 and 18–21 years, were found to have significantly higher risk for testing positive for CT at baseline (OR: 6.7; 95% CI: 1.8, 25.1 and OR: 11.0; 95% CI: 3.3, 36.6, respectively) compared to women age 36–45 years (referent group). Age 14–17 years in the TV group was negatively associated with TV (OR: 0.4; 95% CI: 0.1, 0.3). Black race also remained a significant predictor of both infections, however, with different magnitudes of effect. Black women were more likely to test positive for CT (OR: 2.2; 95% CI 1.6, 3.1) and much more likely to test positive for TV (OR: 6.6; 95%CI: 4.5, 9.7) than white women.

Discussion

Accurately estimating STI prevalence is difficult, but important. Prevalence data guide screening practices which, in turn, facilitate earlier and more comprehensive treatment with the goal of reducing long-term sequelae from infection. The prevalence of STIs in our cohort was higher than that observed in national estimates. We found the prevalence of GC to be 0.4% as compared to 0.1% reported by the CDC. Similarly, our prevalence of CT was much higher at 3.1% compared to 0.43% nationally. Lastly, overall prevalence of TV was found to be 4.9% compared to 3.1% from national estimates, and as high as 8.7% among black women in our study population. Estimates form the NHANES data are more closely reflective of our findings, which report rates of GC at 0.3%, CT at 2.5%, and TV of 3.2%. [17, 18] It should be noted that St. Louis has been shown to have an overall STI positivity rate that is higher than many other metropolitan areas. In 2011, the Missouri department of health reported rates of GC and CT for women residing in St Louis city as 611 per 100,000 and 1454 per 100,000.[19]

Of the 656 women testing positive for one or more STI’s at baseline, 106 (16%) would not have been screened according to current guidelines. These are women who fell outside the age criteria for universal screening and would not have been considered for risk-based testing based on history or current sexual practices. This number confirms that STI prevalence can vary widely among populations, and knowledge of local and population-specific prevalence can be helpful for clinicians to determine how and when to apply national screening guidelines.

There are no current screening guidelines for TV despite its high prevalence. Based on our data, it appears that the risk profiles for TV and CT are different and thus, screening practices should not focus solely on young sexually active women. Prevalence estimation of TV infection is particularly difficult. TV is not a reportable disease and the implications of TV infection are less well established than those of GC and CT. In addition, diagnostic testing is highly variable with the majority of clinicians still relying on saline microscopy (wet mount), which has low sensitivity. By using the specific and sensitive culture technique, we were able to confirm that TV was the most prevalent STI in our cohort. Screening for CT is clearly indicated to prevent the adverse reproductive outcomes of PID and tubal infertility;[20] however the role of TV in the development of PID and infertility is less clear and deserves further study. Routine screening may be indicated if TV is implicated in the etiology of upper genital tract infection and adverse outcomes such as infertility, chronic pain and/or ectopic pregnancy. Trichomoniasis has been identified as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes.[21]

There are several strengths to this study. We were able to implement a universal and consistent screening protocol which allowed for testing of a large cohort of women including women that would not have traditionally been considered for screening. Second, because this was a cohort of women enrolling into a contraceptive study, it was truly a screening protocol. Women were not presenting for care with STI-related symptoms or risk factors. Last, we were able to implement our screening using sensitive and specific diagnostic techniques.

Our study does have limitations. Findings from this study may not be generalizable. As previously mentioned, St. Louis has higher rates of STI positivity than many other urban areas. However, previous studies have shown that despite differences in sampling techniques, CHOICE is largely reflective of both state (2006 Missouri Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System), and national (2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth) surveys.[22] Lastly, national data includes women ages 15–65 when calculating determining rates of STIs. In our cohort, all women were aged 14–45 years. If national prevalence estimates were limited to reproductive –age women, they may actually be more similar to our reported rates.

In summary, prevalence of GC, CT, and TV in our population was higher than national estimates. TV was the most prevalent STI in our cohort, yet it is not a reportable STI and is not recommended as part of the routine screening guidelines. Black women are at a disproportionately higher risk for CT and TV. Lastly, age is an important epidemiologic difference between CT and TV infection: young age is associated with CT and older reproductive age with trichomoniasis.

Summary.

Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC), Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) was higher than current national statistics in a population seeking no-cost contraception.

Acknowledgments

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project was funded by the Susan T. Buffett Foundation. This research was also supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant number UL1 RR024992, National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32 research training grant number 5T32HD055172-03, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) award number K23HD070979

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Madden is a former speaker for Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Peipert JF. Clinical practice. Genital chlamydial infections. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(25):2424–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp030542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweet RL, GRS . Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. In: Sweet GRRL, editor. Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2002. pp. 368–412. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westrom L. Effect of acute pelvic inflammatory disease on fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;121(5):707–13. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90477-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westrom L, et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility. A cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1992;19(4):185–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow JM, et al. The association between Chlamydia trachomatis and ectopic pregnancy. A matched-pair, case-control study. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;263(23):3164–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satterwhite CL, et al. Chlamydia prevalence among women and men entering the National Job Training Program: United States, 2003–2007. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(2):63–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bc097a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoover K, Bohm M, Keppel K. Measuring disparities in the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2008;35(12 Suppl):S40–4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181886750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoover K, Tao G. Missed opportunities for chlamydia screening of young women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(5):1097–102. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816bbe9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoover K, Tao G, Kent C. Low rates of both asymptomatic chlamydia screening and diagnostic testing of women in US outpatient clinics. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):891–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318185a057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrea SB, Chapin KC. Comparison of Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification assay and BD affirm VPIII for detection of T. vaginalis in symptomatic women: performance parameters and epidemiological implications. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(3):866–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02367-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapin K, Andrea S. APTIMA(R) Trichomonas vaginalis, a transcription-mediated amplification assay for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in urogenital specimens. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2011;11(7):679–88. doi: 10.1586/erm.11.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutton M, et al. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(10):1319–26. doi: 10.1086/522532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kent CK, et al. Studies relying on passive retrospective cohorts developed from health services data provide biased estimates of incidence of sexually transmitted infections. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2004;31(10):596–600. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000140011.93104.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Secura GM, et al. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):115 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datta SD, et al. Gonorrhea and chlamydia in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999 to 2002. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;147(2):89–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allsworth JE, Ratner JA, Peipert JF. Trichomoniasis and other sexually transmitted infections: results from the 2001–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2009;36(12):738–44. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b38a4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epidemiologic Profiles of HIV, STD, and Hepatitis in Missouri. 2011 Available from: http://health.mo.gov/data/hivstdaids/pdf/MOHIVSTD2011.pdf.

- 20.Scholes D, et al. Prevention of pelvic inflammatory disease by screening for cervical chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(21):1362–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotch MF, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24(6):353–60. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kittur ND, et al. Comparison of contraceptive use between the Contraceptive CHOICE Project and state and national data. Contraception. 2011;83(5):479–85. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]