Abstract

Carbohydrates as T cell-activating antigens have been generating significant interest. For many years, carbohydrates were thought of as T-independent antigens, however, more recent research had demonstrated that mono- or oligosaccharides glycosidically-linked to peptides can be recognized by T cells. T cell recognition of these glycopeptides depends on the structure of both peptide and glycan portions of the antigen. Subsequently, it was discovered that natural killer T cells recognized glycolipids when presented by the antigen presenting molecule CD1d. A transformative insight into glycan-recognition by T cells occurred when zwitterionic polysaccharides were discovered to bind to and be presented by MHCII to CD4+ T cells. Based on this latter observation, the role that carbohydrate epitopes generated from glycoconjugate vaccines had in activating helper T cells was explored and it was found that these epitopes are presented to specific carbohydrate recognizing T cells through a unique mechanism. Here we review the key interactions between carbohydrate antigens and the adaptive immune system at the molecular, cellular and systems levels exploring the significant biological implications in health and disease.

Keywords: glycoconjugate vaccine, antigen presentation, zwitterionic polysaccharide, glycolipid, glycopeptide, T cell

1. Introduction

The mammalian immune system continually interacts in many ways with microbes and environmental agents composed of biologically complex molecules. Research has traditionally focused on how immune cells interact with proteins, paying comparatively little attention to other prominent biologic molecules such as carbohydrates, which decorate the surface of nearly all microbial classes. The relative lack of interest in immunology research on carbohydrate antigens has been due mainly to their inability to induce an adaptive immune response. With recent advances in analytical and biochemical research tools, we now have a better understanding of the important interactions of carbohydrate antigens with the adaptive arm of the immune system. Carbohydrate-containing antigens include glycolipids, which are presented to T cells by CD1 [1]; glycopeptides containing mono- or oligosaccharides, which are generated by processing of natural glycoproteins [2]; zwitterionic polysaccharides (ZPSs) that activate T cells [3, 4]; and glycoconjugate vaccines [5]. In this article, we review key interactions of carbohydrate-containing antigens with the adaptive immune system and the biological implications of these interactions.

2. Zwitterionic polysaccharides

ZPSs, which have alternating positive and negative charges in each repeating unit, are taken up by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), processed through oxidative reactions by the major histocompatibility class II (MHCII) pathway, and presented to T cells in the context of MHCII [3, 6]. Their zwitterionic motif allows ZPSs processed in the endosome to bind to MHCII, primarily by electrostatic interactions [7]. After ZPS presentation, CD4+ T cells can recognize and respond specifically to these carbohydrates [8, 9]. Non-zwitterionic polysaccharides, which have only negatively charged residues or no charge groups at all, make up the majority of microbial carbohydrates [4, 10]. Of the non-zwitterionic polysaccharides examined to date, all are processed in the endosome by oxidative mechanisms [6] but fail to bind to MHCII and therefore cannot be presented to or activate T cells. Therefore, non-zwitterionic polysaccharides have been considered T cell-independent antigens [4, 11-14]. Polysaccharide A (PSA), which is expressed on the surface of the gram-negative symbiotic bacterium Bacteroides fragilis, is so far the most-studied ZPS. Other ZPSs that have been widely studied include Streptococcus pneumoniae type 1 polysaccharide [15-17] and Staphylococcus aureus type 5 and type 8 polysaccharides [18, 19]. PSA elicits T-cell responses critical to immunologic development [20, 21] and to protection against inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [22].

Studies in our laboratory established the mechanisms for T-cell activation by PSA [3, 6]. Through a series of confocal microscopy and size-exclusion chromatography experiments, we first established that PSA is taken up by APCs and processed into smaller fragments in the endocytic compartments. We then discovered that processed PSA binds to MHCII proteins in endosomes and is presented on the surface of APCs. We showed that the MHCII-presented PSA epitope forms an immune synapse with the T-cell receptor (TCR) of CD4+ T cells. Moreover, we investigated the chemical reactions responsible for processing of PSA in the endocytic compartments [6]. We found that PSA is depolymerized in endosomes through deamination resulting from the action of reactive nitrogen species (RNSs) such as nitric oxide. We further observed that endosomal depolymerization of PSA depends on the upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which is responsible for generation of RNSs [6]. Finally, we demonstrated that iNOS expression in APCs is required for PSA-induced CD4+ T-cell activation.

PSA exerts its immunological activity through multiple mechanisms [4, 23]. Earlier studies focused on the therapeutic and prophylactic roles of PSA in intraabdominal abscess formation [24]. PSA prevents the formation of abscesses by a T cell-dependent mechanism [24-26]. More specifically, PSA-activated splenic T cells prevented abscess induction by B. fragilis or Staphylococcus aureus in mice. T cell-mediated protection against abscess formation was critically dependent on the zwitterionic charge motif of PSA. Elimination of negative or positive charges abolished PSA-mediated stimulation of T cells and, consequently, protection from abscess formation [27].

Our research over the past two decades has substantiated the critical immunomodulatory roles of PSA in the context of the symbiotic relationship between the mammalian immune system and B. fragilis [4, 23]. In one study, we monocolonized germ-free mice with a wild-type, PSA-expressing strain of B. fragilis or with a mutant strain lacking PSA (ΔPSA); we then measured splenic CD4+T-cell numbers to identify the role of PSA in maturation of the adaptive immune system [20]. Mice colonized with PSA-expressing B. fragilis had T-cell numbers similar to those in conventional mice. In contrast, mice monocolonized with the ΔPSA strain had significantly lower numbers of T cells than did conventional mice. B. fragilis corrected for defective T-cell development in germ-free mice through expression of PSA. MHCII presentation of PSA by dendritic cells (DCs) stimulated naïve CD4+ T cells to correct T-cell deficiency in germ-free mice. Furthermore, colonization with a PSA expressing strain of B. fragilis restored normal Th1/Th2 balance from the Th2 skewed phenotype of germ-free mice. These observations, along with our other findings in this study, served as an important illustration of the immunomodulatory activities of symbiotic bacteria residing in the gastrointestinal tract. In a separate study, we assessed the role of PSA in protection from IBD [22], demonstrating that both PSA-expressing B. fragilis and purified PSA protected mice from colitis induced by Helicobacter hepaticus and that PSA-mediated protection was attributable to interleukin (IL) 10 produced by PSA-activated CD4+ T cells. Subsequent work has shown that PSA activates CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells to secrete IL-10.

In short, PSA is one example of an immunomodulatory molecule produced by an important commensal bacterial resident of the gastrointestinal tract. It would be unduly pessimistic to think that there are no other bacterial products that help train our immune system for its maturation. Studies of the human microbiome, which have only recently become trendy, will shed light on the complex and beneficial relationship between human hosts and their bacterial inhabitants.

3. Glycoconjugate vaccines

On the basis of the successful use of the hapten-carrier protein conjugation strategy [28, 29], it has become standard practice to couple capsular polysaccharides (CPSs) from bacterial targets to T cell-dependent carrier proteins to form glycoconjugate vaccines [30-33]. Immunization with glycoconjugates, as opposed to pure polysaccharides, elicits T-cell help for B cells that produce IgG antibodies to the polysaccharide component [4, 34]. In addition to inducing polysaccharide-specific IgM-to-IgG switching, glycoconjugate immunization induces memory B-cell development and T-cell memory [4]. Immunizations with glycoconjugates containing CPSs from Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis have been highly successful in preventing infectious diseases in children caused by these virulent pathogens [33, 35]. The traditional explanation for the mechanism by which glycoconjugates induce humoral immune responses is that the carrier-protein portion of the conjugated vaccine stimulates CD4+ T cells, which, in turn, help B cells to secrete antibodies to glycans through a cognate interaction. Indeed, glycoconjugate vaccines have been developed on the assumption that eliciting a potent humoral response to bacterium-derived CPS requires coupling to a carrier protein that activates CD4+ T cells to help B cells produce the relevant antibodies [4, 13]. The traditional hypothesis of immune activation by glycoconjugate vaccines suggests that only a peptide generated from the glycoconjugate can be presented to and recognized by T cells. This view ignores the synthetic linkage of carbohydrates to proteins in glycoconjugates by extremely strong covalent bonds that are unlikely to be broken within the endosome. Thus the possibility of presentation of peptide bound carbohydrate to T cells is raised. Accordingly, we considered whether T cells can recognize non-zwitterionic carbohydrates (i.e., most CPSs) linked to another molecule (e.g., a peptide) whose binding to MHCII allows presentation of the linked hydrophilic carbohydrate on the APC surface.

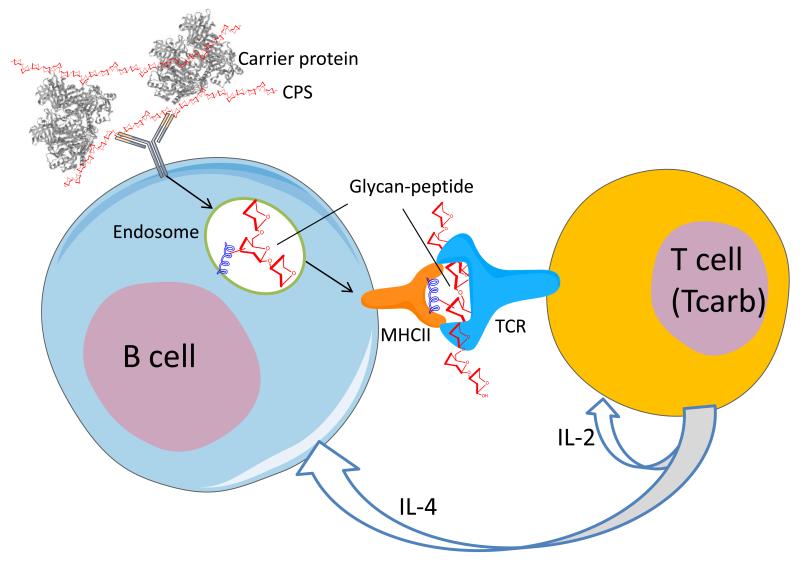

In a recently published study, we uncovered the cellular and molecular mechanisms for adaptive immune responses mediated by glycoconjugate immunization [5]. We demonstrated that, upon uptake by APCs, glycoconjugate vaccines are involved in a depolymerization reaction that yields glycan-peptide—a processed glycan chemically bound to a peptide fragment. Glycan-peptide is displayed on the surface of APCs in the context of an MHCII protein (Fig. 1). Our findings strongly suggest that the peptide portion of the glycan-peptide binds to MHCII and that the hydrophilic glycan is thereby exposed to the TCR of CD4+ T cells on the APC surface. Biochemical and structural analyses of the MHCII and TCR interactions of glycan-peptides will provide critical information about these interactions at the molecular level. We next showed that glycoconjugate immunization induces CD4+ T cells that recognize the carbohydrate portion of the vaccine (Fig. 1). In this study, we isolated lymphocytes from mice immunized with GBSIII-OVA, a glycoconjugate consisting of the type III polysaccharide of group B Streptococcus (GBSIII) coupled to ovalbumin (OVA). We performed an ELISpot assay, co-culturing immune lymphocytes with irradiated syngeneic splenocytes derived from GBSIII-OVA-immunized mice (as APCs) in the presence of various antigens [5, 36]. We found that significantly more immune lymphocytes reacted with GBSIII-TT [GBSIII coupled to tetanus toxoid (TT)] than with either TT or GBSIII alone, with a consequently higher number of IL-2 spots. On the other hand, unconjugated OVA stimulated more immune lymphocytes than did GBSIII-TT [36]. These findings confirmed the presence among immune lymphocytes of T cells that recognize GBSIII as well as T cells that recognize OVA. Therefore, we decided to isolate carbohydrate-specific T cells from the immune lymphocytes. To eliminate OVA-specific T cells, the immune lymphocytes were restimulated with APCs in the presence of GBSIII-TT for an additional 10-14 days [36]. After cloning of immune CD4+ T cells by limiting dilution, the cloned cells were restimulated with GBSIII-OVA-pulsed APCs in culture medium containing the T-cell culture supplement [36]. Finally, we were able to isolate two distinct carbohydrate-specific CD4+ T-cell clones [5]: one recognizing GBSIII in the context of the I-Ad molecule and the other recognizing GBSIII with the I-Ed molecule [5]. Thus we provided irrefutable evidence for the presence of carbohydrate-specific CD4+ T cells, designated Tcarbs (Fig. 1). Since that study, we have established additional Tcarb clones [36]. Two distinct CD4+ T-cell clones secreted both IL-2 and IL-4, but not interferon γ (IFN-γ), in the presence of GBSIII conjugated to any of three carrier proteins: OVA, TT, or hen egg lysozyme [5]. However, none of the clones responded to the unconjugated carrier proteins alone. These data validated the existence of T cells that recognize only the carbohydrate portion of the glycoconjugate vaccine (Tcarb). These T cells were obtained by stimulation first in vivo with III-OVA and subsequently in vitro with III-TT. These findings suggested the possibility that Tcarbs contribute to the protection induced by GBSIII-OVA vaccine.

Fig. 1. Mechanism for T cell mediated adaptive immune response by a glycoconjugate vaccine.

B cell takes up the glycoconjugate through its carbohydrate-recognizing B cell receptor (BCR) and processes into glycan-peptides in the endosome. Peptide portion of the glycan-peptide binds to MHCII and glycan portion is presented to the TCR of Tcarb. Stimulated Tcarb secretes IL-2 and IL-4 to induce carbohydrate-specific adaptive immune response (e.g., B and T cell proliferation, B and T cell memory, antibody class switch (IgM to IgG)).

In a series of immunization experiments, we investigated the relative contributions of peptide- and carbohydrate-specific T cells to the induction of a carbohydrate-specific IgG response. Mice primed and boosted with GBSIII-OVA had GBSIII-specific IgG levels similar to those in mice primed with GBSIII-OVA and boosted with GBSIII-TT. Since GBSIII is the only shared antigen in the latter immunization group, this observation suggested that Tcarbs were primarily responsible for the GBSIII-specific adaptive immune response.

Demystifying T-cell activation mechanisms of glycoconjugate vaccines was a key step towards designing new-generation vaccines. We learned from our mechanistic studies that the most important feature of an ideal glycoconjugate vaccine would be enrichment for its glycan-peptide epitopes. Motivated by this information, we designed and synthesized a prototype new-generation glycoconjugate vaccine and tested it for immunogenicity and protective capacity in comparison with a traditional counterpart [5]. Our results showed that the new-generation vaccine was strikingly more immunogenic and protective than the traditional glycoconjugate vaccine [5]. These findings strongly suggested that Tcarbs significantly contribute to the protection induced by a glycoconjugate vaccine.

It is well established that antibodies to CPSs mediate protection against challenge by encapsulated bacteria [4]. Therefore, from the standpoint of vaccine development, it is imperative to investigate whether Tcarbs can function as helper T (Th) cells to promote the secretion of antibody to CPSs by B cells, with consequent protection against bacterial infection. By shedding light on the important role played by this newly identified subset of CD4+ T cells, our study may represent the dawn of a new paradigm in T-cell biology that will lead to radical advances in the development of glycoconjugate-based vaccines against bacterial pathogens.

4. Glycopeptides and glycolipids

The adaptive immune system interacts with protein antigens through well-defined mechanisms [37]. Recently, important interactions of T cells with glycopeptide and glycolipid antigens have been discovered. Glycopeptides containing glycosidically linked mono- or oligosaccharides, which are generated from glycoproteins, or glycopeptides generated by coupling peptides with small oligosaccharides are recognized by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells [2, 38-46]. In addition, glycopeptides containing tumor-associated mono- or oligosaccharides are recognized by T cells [47, 48]. Recently, a number of synthetic vaccines comprising tumor-associated glycopeptides have been shown to elicit humoral immune responses to cancer cells expressing tumor-associated carbohydrates [49].

Unique T cells expressing an invariant TCR as well as an NK marker, such as NK1.1 (in mice) or CD161 (in humans), are called invariant natural-killer T (iNKT) cells [50, 51]. Unlike conventional T cells, iNKT cells do not recognize peptide antigens presented by polymorphic MHCI or MHCII molecules, but rather recognize glycolipid antigens presented by the non-polymorphic MHCI-like molecule CD1d [1, 50-54]. Since the CD1d molecule is highly conserved between humans and mice, the mouse model can be used to predict CD1d-dependent iNKT-cell responses in humans [55]. α-Galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) is a glycolipid antigen known to be specific for iNKT cells. Its two lipid tails fit tightly into a CD1d-binding groove, whereas its galactose head extends above the surface of the lipid-binding groove and thereby is exposed for recognition by the TCR of iNKT cells (Fig. 2) [56-58]. After presentation of α-GalCer by CD1d molecules, α-GalCer activates iNKT cells to rapidly produce large quantities of Th1 and Th2 cytokines—such as IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively—and subsequently induces the activation of a cascade of various immunocompetent cells, including DCs, NK cells, B cells, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2) [51]. α-GalCer can therefore be used not only as potential direct therapy for cancer and for autoimmune and infectious diseases [59-68] but also as an adjuvant to enhance the efficacy of various existing or future vaccines [69-73]. We have recently identified a novel α-GalCer analog, 7DW8-5, that stimulates iNKT cells more potently than does α-GalCer [74]. In addition, this glycolipid induces maturation and activation of DCs more strongly than does α-GalCer. The more potent biological activity of 7DW8-5 seems to be due to its greater binding affinity to CD1d molecules [74]. We found that, compared with its parental compound α-GalCer, 7DW8-5 displays more potent adjuvant activity on both DNA-based and adenoviral vector-based vaccines against malaria and HIV infection in mice [74, 75]. We are currently poised to move forward into phase 1 clinical trials using 7DW8-5 as an adjuvant.

Fig. 2. Mode of iNKT activation by glycolipids and subsequent activation of various immune competent cells.

Glycolipids presented by CD1d molecules activate iNKT cells, which in turn induce activation/maturation of DCs and subsequent activation of NK, B, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

5. Conclusions

Contrary to the traditional view suggesting that carbohydrates are T cell-independent antigens, we have come to understand that a lack of T-cell response to carbohydrates is due to a failure of these molecules to bind to MHCII, not to an inability of T cells to recognize presented carbohydrates. There are now numerous examples of carbohydrate recognition by T cells. The traditional view of glycoconjugate action [4, 13, 37] is based on the failure of most pure polysaccharides to elicit IgG memory in mice. This paradigm assumes that polysaccharide-specific IgG responses as well as B- and T-cell memory responses induced by glycoconjugate immunization are mediated by MHCII presentation of peptides (derived by protein processing) to the TCR. However, carbohydrates are processed in the endolysosome by reactive oxygen species or RNSs and, if bound to MHCII, are presented to and recognized by the TCR [3-6]. Non-zwitterionic carbohydrates can be processed to smaller size in APC endosomes [6] but fail to bind directly to MHCII and therefore are not presented to T cells. In this review, we have discussed several examples of the presentation of carbohydrate-containing antigens to different subclasses of T cells. ZPSs bind directly to MHCII proteins and are presented to T cells. On the other hand, processing of glycoconjugate vaccines in the endosomes of APCs yields glycan-peptides whose peptide portions bind to MHCII so that glycan portions can be presented to T cells. In glycoconjugates, a high-molecular-weight glycan (~10 kDa) is presented to T cells, and TCR recognition is not dependent on the peptide to which the carbohydrate is bound. Documentation of the existence of Tcarbs (T cells that recognize carbohydrates only) is a major step forward in our elucidation of how the adaptive immune system functions. GBSIII—the model polysaccharide antigen used in our studies—is a typical anionic CPS that does not bind to MHCII. Our study offers an explanation for adaptive immune activation by other glycoconjugate vaccines. However, the general applicability of our findings has yet to be tested with other glycoconjugate vaccines, and new repertoires of carbohydrate-recognizing T cells will need to be isolated.

The prevalence of a variety of complex biologic molecules in microbial organisms suggests that mammals evolved an immune system equipped to handle molecules other than proteins. The current understanding of the adaptive immune system is based primarily on protein antigens, although carbohydrates adorn the surfaces of organisms from all microbial kingdoms. If mammals evolved a major class of immune cells—T cells—that cannot recognize foreign carbohydrate structures, such a gap in immunity would seriously weaken the capacity to resist infection and therefore it is highly unlikely that such a gap exists.

Knowledge of the basic mechanisms governing carbohydrate presentation to T cells is essential to an understanding of human immunity to microbes. New insights into carbohydrate processing, presentation, and T-cell activation raise the possibility of novel carbohydrate-based vaccines and therapeutics with chemical and physical properties designed in light of specific information on antigen presentation.

Highlights.

ZPSs elicit immunomodulatory activities in T cells after presentation by MHCII.

Carbohydrate epitopes generated from glycoconjugates are presented to T cells.

Tcarbs are monoclonal T-cell populations that recognize only carbohydrates.

Understanding immune mechanisms is essential for designing new-generation vaccines.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the following grants: US National Institute of Health AI-089915, AI-070258, AI-081510 and from Novartis Vaccines, Siena, Italy.

Abbreviations

- ZPSs

zwitterionic polysaccharides

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- MHCII

major histocompatibility class II

- PSA

polysaccharide A

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- RNSs

reactive nitrogen species

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- DCs

dendritic cells

- IL

interleukin

- CPSs

capsular polysaccharides

- GBSIII

type III polysaccharide of group B Streptococcus

- OVA

ovalbumin

- TT

tetanus toxoid

- Tcarbs

T cells that recognize carbohydrates only

- BCR

B-cell receptor

- IFN-γ

interferon γ

- iNKT

invariant natural-killer T

- α-GalCer

α-galactosylceramide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD1: antigen presentation and T cell function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:817–890. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dzhambazov B, Holmdahl M, Yamada H, Lu S, Lestberg M, Holm B, et al. The major T cell epiope on type II collagen is glycosylated ion normal cartilage but modified by arthritis in both rats and humans. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:357–366. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cobb BA, Wang Q, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. Polysaccharide processing and presentation by the MHCII pathway. Cell. 2004;117:677–687. doi: 10.016/j.cell.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Avci FY, Kasper DL. How Bacterial Carbohydrates Influence the Adaptive Immune System. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:29–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Avci FY, Li XM, Tsuji M, Kasper DL. A mechanism for glycoconjugate vaccine activation of the adaptive immune system and its implications for vaccine design. Nat Med. 2011;17:1602–1610. doi: 10.1038/nm.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Duan J, Avci FA, Kasper DL. Microbial carbohydrate depolymerization by antigen-presenting cells: Deamination prior to presentation by the MHCII pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800974105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cobb BA, Kasper DL. Characteristics of carbohydrate antigen binding to the presentation protein HLA-DR. Glycobiology. 2008;18:707. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stingele F, Corthesy B, Kusy N, Porcelli SA, Kasper DL, Tzianabos AO. Zwitterionic Polysaccharides Stimulate T Cells with No Preferential Vbeta Usage and Promote Anergy, Resulting in Protection against Experimental Abscess Formation. J Immunol. 2004;172:1483–1490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Groneck L, Schrama D, Fabri M, Stephen TL, Harms F, Meemboor S, et al. Oligoclonal CD4+ T cells promote host memory immune responses to zwitterionic polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3705–3712. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01492-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ovodov YS. Bacterial Capsular Antigens. Structural Patterns of Capsular Antigens. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2006;71:937–954. doi: 10.1134/s000629790609001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Coutinho A, Moller G. B cell mitogenic properties of thymus-independent antigens. Nature New Biol. 1973;245:12–14. doi: 10.1038/newbio245012a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Barrett DJ. Human immune responses to polysaccharide antigens: an analysis of bacterial polysaccharide vaccines in infants. Adv Pediatr. 1985;32:139–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Guttormsen H-K, Sharpe AH, Chandraker AK, Brigtsen AK, Sayegh MH, Kasper DL. Cognate stimulatory B-Cell-T-Cell interactions are critical for T-cell help recruited by glycoconjugate vaccines. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6375–6384. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6375-6384.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Guttormsen HK, Wetzler LM, Finberg RW, Kasper DL. Immunologic memory induced by a glycoconjugate vaccine in a murine adoptive lymphocyte transfer model. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2026. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2026-2032.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Velez CD, Lewis CJ, Kasper DL, Cobb BA. Type I Streptococcus pneumoniae carbohydrate utilizes a nitric oxide and MHC II-dependent pathway for antigen presentation. Immunology. 2009;127:73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stephen TL, Fabri M, Groneck L, Roehn TA, Hafke H, Robinson N, et al. Transport of Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide in MHC class II tubules. Plos Pathogens. 2007:3. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Trück J, Lazarus R, Clutterbuck EA, Bowman J, Kibwana E, Bateman EA, et al. The zwitterionic type I Streptococcus pneumoniae polysaccharide does not induce memory B cell formation in humans. Immunobiology. 2013;218:368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tzianabos AO, Wang JY, Lee JC. Structural rationale for the modulation of abscess formation by Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9365–9370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161175598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McLoughlin RM, Lee JL, Kasper DL, Tzianabos AO. IFN-γ Regulated Chemokine Production Determines the Outcome of Staphylococcus aureus Infection1. J Immunol. 2008;181:1323–1332. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;122:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mazmanian SK, Kasper DL. The love-hate relationship between bacterial polysaccharides and the host immune system. Nature Rev Immunol. 2006;6:849–858. doi: 10.1038/nri1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–625. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Surana NK, Kasper DL. The yin yang of bacterial polysaccharides: lessons learned from B. fragilis PSA. Immunol Rev. 2012;245:13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL, Cisneros RL, Smith RS, Onderdonk AB. Polysaccharide-mediated protection against abscess formation in experimental intra-abdominal sepsis. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2727–2731. doi: 10.1172/JCI118340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tzianabos AO, Onderdonk AB, Smith RS, Kasper DL. Structure-function relationships for polysaccharide-induced intra-abdominal abscesses. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3590–3593. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3590-3593.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tzianabos AO, Russell PR, Onderdonk AB, Gibson FC, 3rd, Cywes C, Chan M, et al. IL-2 mediates protection against abscess formation in an experimental model of sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;163:893–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tzianabos AO, Finberg RW, Wang Y, Chan M, Onderdonk AB, Jennings HJ, et al. T cells activated by zwitterionic molecules prevent abscesses induced by pathogenic bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6733–6740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mitchison NA. The carrier effect in the secondary response to hapten-protein conjugates. II. Cellular cooperation. Eur J Immunol. 1971;1:18–25. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mitchison NA. The carrier effect in the secondary response to haptenprotein conjugates. I. Measurement of the effect with transferred cells and objections to the local environment hypothesis. Eur J Immunol. 1971;1:10–17. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830010103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Beuvery EC, Van Rossum F, Nagel J. Comparison of the induction of immunoglobulin M and G antibodies in mice with purified pneumococcal type III and meningococcal group C polysaccharides and their protein conjugates. Infect Immun. 1982;37:15–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.1.15-22.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schneerson R, Barrera O, Sutton A, Robbins JB. Preparation, characterization,and immunogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide-protein conjugates. J Exp Med. 1980;152:361–376. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wessels MR, Paoletti LC, Rodewald AK, Michon F, DiFabio J, Jennings HJ, et al. Stimulation of protective antibodies against type Ia and Ib group B streptococci by a type Ia polysaccharide-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4760–4766. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4760-4766.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Weintraub A. Immunology of bacterial polysaccharide antigens. Carbohydr Res. 2003;338:2539–2547. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mitchison NA. T-cell-B-cell cooperation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:308–312. doi: 10.1038/nri1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Trotter CL, McVernon J, Ramsay ME, Whitney CG, Mulholland EK, Goldblatt D, et al. Optimising the use of conjugate vaccines to prevent disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b, Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vaccine. 2008;26:4434–4445. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Avci FY, Li X, Tsuji M, Kasper DL. Isolation of carbohydrate-specific CD4(+) T cell clones from mice after stimulation by two model glycoconjugate vaccines. Nature Protocols. 2012;7:2180–2192. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Janeway CA, Travers P, Walport M, Chlomchik M. Immunobiology. 6th ed. Garland Science Publishing; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Deck B, Elofsson M, Kihlberg J, Unanue ER. Specificity of Glycopeptide-Specific T Cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:1074–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mouritsen S, Meldal M, Christiansenbrams I, Elsner H, Werdelin O. Attachment of Oligosaccharides to Peptide Antigen Profoundly Affects Binding to Major Histocompatibility Complex Class-Ii Molecules and Peptide Immunogenicity. European Journal of Immunology. 1994;24:1066–1072. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Haurum JS, Arsequell G, Lellouch AC, Wong SYC, Dwek RA, McMichael AJ, et al. Recognition of Carbohydrate by Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I-Restricted, Glycopeptide-Specific Cytotoxic T-Lymphocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;180:739–744. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Haurum JS, Tan L, Arsequell G, Frodsham P, Lellouch AC, Moss PAH, et al. Peptide anchor residue glycosylation: Effect on class I major histocompatibility complex binding and cytotoxic T lymphocyte recognition. European Journal of Immunology. 1995;25:3270–3276. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].AbdelMotal UM, Berg L, Rosten A, Bengtsson M, Thorpe CJ, Kihlberg J, et al. Immunization with glycosylated K-b-binding peptides generates carbohydrate-specific, unrestricted cytotoxic T cells. European Journal of Immunology. 1996;26:544–551. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ishioka GY, Lamont AG, Thomson D, Bulbow N, Gaeta FCA, Sette A, et al. MHC INTERACTION AND T-CELL RECOGNITION OF CARBOHYDRATES AND GLYCOPEPTIDES. J Immunol. 1992;148:2446–2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Werdelin O, Meldal M, Jensen T. Processing of glycans on glycoprotein and glycopeptide antigens in antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9611–9613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152345899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Corthay A, Backlund J, Broddefalk J, Michaelsson E, Goldschmiddt T, Kilberg J, et al. Epitope glycosylation plays a critical role for T cell recognition of type II collagen in collagen-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2580–2590. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2580::AID-IMMU2580>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Harding CV, Kihlberg J, Elofsson M, Magnusson G, Unanue ER. Glycopeptides Bind Mhc Molecules and Elicit Specific T-Cell Responses. J Immunol. 1993;151:2419–2425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gad M, Werdelin O, Meldal M, Komba S, Jensen T. Characterization of T cell hybridomas raised against a glycopeptide containing the tumor-associated T antigen, (beta Gal (1-3) alpha GalNAc-O/Ser) Glycoconjugate J. 2002;19:59–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1022537031617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].GalliStampino L, Meinjohanns E, Frische K, Meldal M, Jensen T, Werdelin O, et al. T-cell recognition of tumor-associated carbohydrates: The nature of the glycan moiety plays a decisive role in determining glycopeptide immunogenicity. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3214–3222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ingale S, Awolfert M, Gaekwad J, Buskas T, Boons GJ. Robust immune responses elicited by a fully synthetic three-component vaccine. Nature Chemical Biology. 2007;3:663–667. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bendelac A, Rivera MN, Park SH, Roark JH. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: Development, specificity, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:535–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kronenberg M. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: Progress and paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sieling PA, Chatterjee D, Porcelli SA, Prigozy TI, Mazzaccaro RJ, Soriano T, et al. Cd1-Restricted T-Cell Recognition of Microbial Lipoglycan Antigens. Science. 1995;269:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.7542404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Moody DB, Reinhold BB, Guy MR, Beckman EM, Frederique DE, Furlong ST, et al. Structural requirements for glycolipid antigen recognition by CD1b-restricted T cells. Science. 1997;278:283–286. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kawano T, Cui JQ, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of V(alpha)14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Brossay L, Chioda M, Burdin N, Koezuka Y, Casorati G, Dellabona P, et al. CD1d-mediated recognition of an alpha-galactosylceramide by natural killer T cells is highly conserved through mammalian evolution. J Exp Med. 1998;18:1521–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Koch M, Stronge VS, Shepherd D, Gadola SD, Mathew B, Ritter G, et al. The crystal structure of human CD1d with and without alpha-galactosylceramide. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:819–826. doi: 10.1038/ni1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Borg NA, Wun KS, Kjer-Nielsen L, Wilce MCJ, Pellicci DG, Koh R, et al. CD1d-lipid-antigen recognition by the semi-invariant NKT T-cell receptor. Nature. 2007;448:44–49. doi: 10.1038/nature05907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Tsuji M. Glycolipids and phospholipids as natural CD1d-binding NKT cell ligands. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1889–1898. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6073-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kawano T, Cui JQ, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Sato H, et al. Natural killer-like nonspecific tumor cell lysis mediated by specific ligand-activated V alpha 14 NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5690–5693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Crowe NY, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. A critical role for natural killer T cells in immunosurveillance of methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas. J Exp Med. 2002;196:119–127. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hong S, Wilson MT, Serizawa I, Wu L, Singh N, Naidenko OV, et al. The natural killer T-cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide prevents autoimmune diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2001;7:1052–1056. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Sharif S, Arreaza GA, Zucker P, Mi QS, Sondhi J, Naidenko OV, et al. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide treatment prevents the onset and recurrence of autoimmune Type 1 diabetes. Nat Med. 2001;7:1057–1062. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Jahng AW, Maricic I, Pedersen B, Burdin N, Naidenko O, Kronenberg M, et al. Activation of natural killer T cells potentiates or prevents experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1789–1799. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Singh AK, Wilson MT, Hong SM, Olivares-Villagomez D, Du CG, Stanic AK, et al. Natural killer T cell activation protects mice against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1801–1811. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kakimi K, Guidotti LG, Koezuka Y, Chisari FV. Natural killer T cell activation inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:921–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Chackerian A, Alt J, Perera V, Behar SM. Activation of NKT cells protects mice from tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6302–6309. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6302-6309.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kawakami K, Kinjo Y, Yara S, Koguchi Y, Uezu K, Nakayama T, et al. Activation of V alpha 14(+) natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide results in development of Th1 response and local host resistance in mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2001;69:213–220. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.213-220.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, de Oliveira C, Tomaska M, Hong S, Bruna-Romero O, Nakayama T, et al. alpha-Galactosylceramide-activated V alpha 14 natural killer T cells mediate protection against murine malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8461–8466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Silk JD, Hermans IF, Gileadi U, Chong TW, Shepherd D, Salio M, et al. Utilizing the adjuvant properties of CD1d-dependent NK T cells in T cell-mediated immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1800–1811. doi: 10.1172/JCI22046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Hermans IF, Silk JD, Gileadi U, Salio M, Mathew B, Ritter G, et al. NKT cells enhance CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cell responses to soluble antigen in vivo through direct interaction with dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:5140–5147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Fujii S, Shimizu K, Smith C, Bonifaz L, Steinman RM. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J Exp Med. 2003;198:267–279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Van Kaer L, Bergmann CC, Wilson JM, Schmieg J, Kronenberg M, et al. Natural killer T cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide enhances protective immunity induced by malaria vaccines. J Exp Med. 2002;195:617–624. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Fraser KA, Pica N, Carnero E, Moran TM, Franck RW, et al. Alpha-C-galactosylceramide as an adjuvant for a live attenuated influenza virus vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:3766–3774. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Li XM, Fujio M, Imamura M, Wu D, Vasan S, Wong CH, et al. Design of a potent CD1d-binding NKT cell ligand as a vaccine adjuvant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006662107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Padte NN, Li XM, Tsuji M, Vasan S. Clinical development of a novel CD1d-binding NKT cell ligand as a vaccine adjuvant. Clin Immunol. 2011;140:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]