Abstract

Apoptosis is a key mechanism for enhanced cellular radiosensitivity in radiation therapy. Studies suggest that Akt signaling may play a role in apoptosis and radioresistance. This study evaluates the possible modulating role of amiloride, an antihypertensive agent with a modulating effect to alternative splicing for regulating apoptosis, in the antiproliferative effects induced by ionizing radiation (IR) in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) 8401 cells. Analysis of cell viability showed that amiloride treatment significantly inhibited cell proliferation in irradiated GBM8401 cells (p<0.05) in a time-dependent manner, especially in cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment. In comparison with GBM8401 cells treated with amiloride alone, with GBM8401 cells treated with IR alone, and with human embryonic lung fibroblast control cells (HEL 299), GBM8401 cells treated with IR combined with amiloride showed increased overexpression of phosphorylated Akt, regardless of whether IR treatment was performed before or after amiloride administration. The alternative splicing pattern of apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (APAF1) in cells treated with amiloride alone, IR alone, and combined amiloride-IR treatments showed more consistent cell proliferation compared to that in other apoptosis-related genes such as baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5 (BIRC5), Bcl-X, and homeodomain interacting protein kinase-3 (HIPK3). In GBM8401 cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment, the ratio of prosurvival (-XL,-LC) to proapoptotic (-LN,-S) splice variants of APAF1 was lower than that seen in cells treated with amiloride with IR pretreatment, suggesting that proapoptotic splice variants of APAF1 (APAF1-LN,-S) were higher in the glioblastoma cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment, as compared to glioblastoma cells and fibroblast control cells that had received other treatments. Together, these results suggest that amiloride modulates cell radiosensitivity involving the Akt phosphorylation and the alternative splicing of APAF1, especially for the cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment. Therefore, amiloride may improve the effectiveness of radiation therapy for GBMs.

Treatment of irradiated GBM tumors with amiloride inhibited cell proliferation in a time-dependent manner. Drug treatment alone showed increased expression of pAkt.

Introduction

Irradiation causes DNA damage and induces cell death via apoptosis, mitotic catastrophe, autophage, or senescence (Dunne et al., 2003; Ishikawa et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2012; Salem et al., 2012). However, since cells may survive DNA damage by activating survival signal pathways (Cataldi et al., 2009), cellular radiosensitivity, an important factor in the tumor response to radiotherapy, may be affected by the balance between cell death and survival.

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (Akt) signaling pathway is essential for regulating cell proliferation and is often deregulated in cancers (Willems et al., 2012). The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is also a therapeutic target in grade IV brain tumors (Holand et al., 2011). Upregulated Akt activity and levels are reportedly associated with radioresistance (Shimura, 2011), and Akt signaling may have an important role in apoptosis (Liang and Slingerland, 2003; Lu et al., 2008; Gu et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2012) and radioresistance (Shimura, 2011).

Apoptosis is a key mechanism for achieving an effective therapeutic response to radiation therapy (Salem et al., 2012). This programmed cell death is activated by distinct cellular stresses, such as growth factor withdrawal and DNA damage (Letai, 2006). Several genes, such as apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (APAF1), survivin (baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5 [BIRC5]), and homeodomain interacting protein kinase-3 (HIPK3), are known to have roles in cellular apoptotic processes. For example, because APAF1 homo-oligomerizes into a caspase-activating complex, it plays an essential role in apoptotic signaling. By recruiting and activating caspase-9, the complex forms apoptosome, which results in a proteolytic cascade and the activation of caspase-3 and caspase-7 (Bratton and Salvesen, 2010). The BIRC5 directly inhibits apoptosis by binding to caspases (Filippi-Chiela et al., 2011). The HIPK3 negatively regulates Fas-mediated apoptosis, the dysfunction of which is associated with several diseases such as autoimmune disease and cancer (Stupp et al., 2005). Since modulated expression of these apoptotic genes may affect apoptosis, these modulating effects may alter sensitivity to radiation therapy.

Damage to DNA can induce apoptosis, and several apoptotic genes may be modified via alternative splicing (Munoz et al., 2009). Alternative splicing is an important post-transcriptional modification that generates diverse RNA isoforms and functions (Tiziano et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2012). Since many alternative splicing variants of apoptotic factors have antagonistic functions (Schwerk and Schulze-Osthoff, 2005), studies suggest that the effectiveness of cancer therapies may be improved by manipulating alternative splicing genes to increase radiosensitivity. Amiloride is a potassium-sparing diuretic used to treat hypertension (Bull and Laragh, 1968). Recently, Chang et al. (2011b) discovered that amiloride plays a novel biological role in modulating alternative splicing and in inducing apoptosis in leukemic cells. Amiloride also has a transcriptome-wide effect on the alternative splicing of RNA transcripts, particularly in apoptotic genes (Chang et al., 2011b).

Radiotherapy is the standard therapy for high-grade glioblastoma such as glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) (Yasui and Owens, 2012). However, its efficacy is limited by the radioresistance that is generated during the course of irradiation (Bao et al., 2006; Fedrigo et al., 2011; Filippi-Chiela et al., 2011). Therefore, this study investigated the possible modulating effect of amiloride on irradiation-induced antiproliferation of human brain GBM8401 cells and evaluated its effects on Akt signaling and on alternative splicing in four apoptotic genes.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and ionizing radiation exposure

Human GBM8401 cells and human fibroblast HEL 299 cells obtained from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan) were grown in the DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Amiloride (Sigma Chemical) treatment was performed as previously described (Chang et al., 2011a). At specified times, cells were irradiated with a single dose of 5 Gy at room temperature by a Varian 2100 C/D linear accelerator (Varian Medical System) at a dose rate of 300 MU/min (3 Gy/min) and at a source-to-target distance of 100 cm.

Cell viability inhibition assay

The trypan blue dye exclusion method (Chiu et al., 2009; Yen et al., 2010) was used to measure the viability of cells treated with 0.2 mM amiloride and/or 5 Gy ionizing radiation (IR) for the time intervals of 24, 48, and 72 h. Exponentially grown cells (1×104) were plated in 96-well plates until 90% confluence was achieved. The cells were then treated with 0.2% trypan blue and counted with a hemocytometer (Sigma-Aldrich). Each treatment was performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

Cells treated with 0.2 mM amiloride and/or 5 Gy IR were harvested and denatured by mixing with a lysis buffer at 4°C for 20 min. After centrifuging the lysates, protein concentrations were determined with a BSA protein assay kit (Pierce). Equal amounts of proteins were loaded onto sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide (10%) gels for electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Each membrane was then blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in a TBST buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h and washed with the same buffer. After incubation with the desired primary antibodies, the cells were washed and treated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The signal intensities were measured using LabWorks software (UVP BioImaging Systems).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction for alternative splicing analysis

After treatment with 0.2 mM amiloride and/or 5 Gy IR, mRNA was extracted from the cells using a TurboCapture 8 mRNA kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription (RT) of the mRNA was performed using a mixture of oligo(dT), random primers, and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega). Table 1 shows the specific primer pairs used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In these genes, the ratios of prosurvival splice variants to proapoptotic splice variants were calculated according to their relative gel densities measured using the UVP BioImaging Systems with LabWorks software.

Table 1.

Primers Used for Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Four Alternative Splicing Genes

| Genes | Forward primers | Reverse primers | Tma | Size (bp)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APAF1 | CAGCTGATGGAACCTTAAAGC | GTCTGGTCATCAGAAGATGTC | 62.0 | 430, 301 |

| BIRC5 | CACCGCATCTCTACATTCAA | CACTTTCTCCGCAGTTTCCT | 60.0 | 345, 227 |

| Bcl-X | GAGGCAGGCGACGAGTTTGAA | TGGGAGGGTAGAGTGGATGGT | 56.0 | 460, 271 |

| HIPK3 | AGCCTGCCACTACCAAGAAA | CAGCAATTTCTTGCCTCTCC | 58.0 | 244, 181 |

Annealing temperature for polymerase chain reaction.

Alternative splicing size.

APAF1, apoptotic protease-activating factor-1; BIRC5, baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5; HIPK3, homeodomain interacting protein kinase-3.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean±SD. The Student's t-test was performed to determine significant differences between experimental groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of amiloride on irradiation-induced cell death

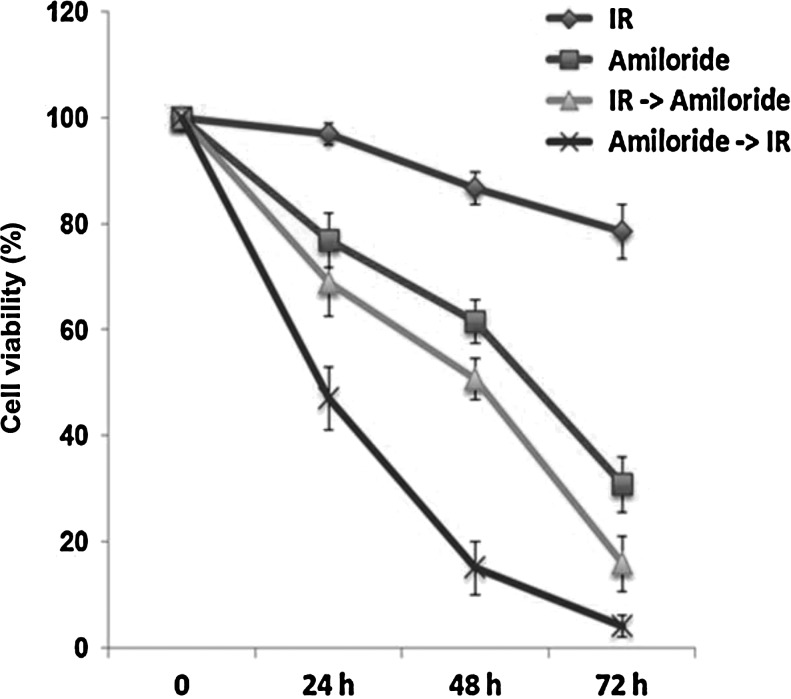

Figure 1 shows that, compared to cells treated with amiloride alone or with IR alone, the cell death effect was enhanced in cells treated with amiloride with IR pre- and post-treatments. Additionally, cell death was significantly higher in cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment as compared to cells treated with amiloride with IR pretreatment (p<0.05). All these treatments displayed antiproliferation in a time-dependent manner.

FIG. 1.

Viability of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) 8401 cells treated with amiloride with ionizing radiation (IR) pre- and post-treatments. Viabilities of GBM8401 cells treated with IR alone, with 0.2 mM amiloride alone, with amiloride with IR pretreatment (IR→amiloride), and with amiloride with IR post-treatment (amiloride→IR) for varying incubation times. In cells treated with amiloride alone or with IR alone, cell viabilities were measured over three time intervals. In the IR→amiloride cells, irradiation with 5 Gy was immediately followed by incubation with amiloride for three time intervals. The amiloride→IR cells were treated with amiloride for 24 h, washed, irradiated with 5 Gy, and then incubated in an amiloride-free medium for three time intervals.

Effect of IR and amiloride on phosphorylation of Akt protein

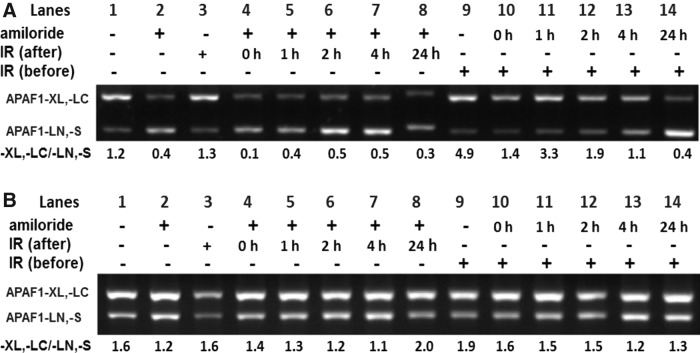

Since the PI3K/Akt pathway is essential for regulating cell proliferation and survival, this study first evaluated Akt and phosphorylated Akt (p-Ser-Akt) levels in GBM8401 cells treated with IR alone, amiloride alone, and amiloride of IR pre- and post-treatments. None of the treatments significantly affected Akt levels in the cells (Fig. 2). However, phosphorylated Akt (p-Ser-Akt) levels were significantly higher in cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment (after; lanes 4–8) and in cells treated with amiloride with IR pretreatment (before; lanes 9–14) compared to untreated control cells, cells treated with amiloride alone, and cells treated with IR alone (lanes 1–3, respectively). These data suggest that the amiloride/IR combined treatments, that is, both IR (after) and IR (before), activated Akt phosphorylation in the GBM8401 glioblastoma cells. In contrast, in human embryonic lung fibroblast control cells (HEL 299) treated with amiloride and/or IR (Fig. 2B), phosphorylated Akt levels were only half those observed in glioblastoma cells (Fig. 2A). Notably, IR reportedly induces Akt phosphorylation in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells and in cervical cancer HeLa cells (Shimura, 2011).

FIG. 2.

Expressions of the p-Akt protein were measured at different incubation times in GBM8401 cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment (amiloride→IR) and in GBM8401 cells treated with amiloride with IR pretreatment (IR→amiloride). (A) The amiloride→IR cells and IR→amiloride cells were incubated for the indicated times. (B) Similar experiments were performed in human fibroblast HEL 299 cells. The amiloride→IR cells were treated with 0.2 mM amiloride for 24 h, irradiated with IR 5 Gy, and then incubated in an amiloride-free medium for varying durations. The IR→amiloride cells were irradiated with IR 5 Gy and immediately incubated with amiloride for varying durations. The control cells were not treated with either amiloride or IR. The p-Ser-Akt/Akt ratios for protein levels in the treated cells were calculated in reference to the control cells. Lanes indicate the conditions for control, amiloride with IR pre- or post-treatments with different incubation times.

Effect of amiloride and IR on alternative splicing of apoptotic genes

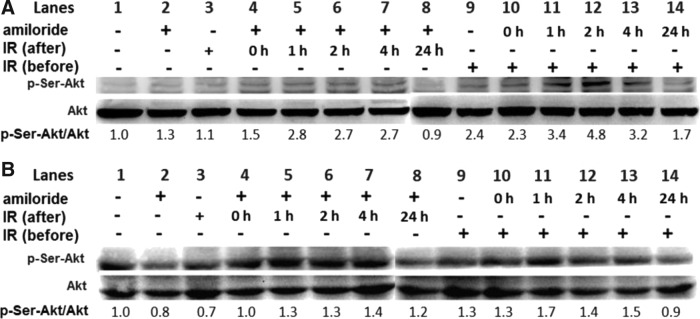

In amiloride-treated cells for IR post- and pretreatments (Fig. 3A, B, respectively), proapoptotic splice variants of APAF1 (APAF1-LN,-S) increased concomitantly with a decrease in the prosurvival splice variants APAF-XL,-LC. The ratio of prosurvival splice variants of APAF1 to proapoptotic splice variants of APAF1 was lower (Fig. 3C) than that found in controls and was positively correlated with cell survival (Fig. 1). In APAF1, treatment with IR alone did not substantially change the -XL,-LC/-LN,-S ratio (Fig. 3C) and nor did it dramatically increase cell death as compared to the combined treatments with amiloride and IR (Fig. 1).

FIG. 3.

Effects of combined treatment with amiloride and IR on the alternative splicing of various apoptotic genes in GBM8401 cells. (A) The results of reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis showed that alternatively spliced isoforms of PCR products in four apoptotic genes (A) were amplified by the individual variant-specific primers shown in Table 1. (B) The RT-PCR products were resolved by agarose gels. (C) In densitometric analyses of the agarose gels, relative intensities of individual spliced variants were normalized to those of the untreated controls. Cells treated with amiloride (Ami) alone were incubated for 24 h in 0.2 mM amiloride, washed, and then incubated in an amiloride-free medium for another 24 h. Cells treated with IR alone were irradiated with 5 Gy and incubated in an amiloride-free medium for 24 h. In cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment (amiloride→IR), 24-h treatment with amiloride was followed by washing, irradiation with 5 Gy, and a 24-h incubation in an amiloride-free medium. In cells treated with amiloride with IR pretreatment (IR→amiloride), irradiation with 5 Gy was immediately followed by a 24-h incubation with amiloride. *Significant difference between cells treated with amiloride with IR pre- and post-treatments.

Cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment also showed a lower ratio of -XL,-LC/-LN,-S as compared to cells treated with amiloride with IR pretreatment. Although the difference did not reach a statistical significance (p=0.06), cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment had more proapoptotic splice variants (APAF1-LN,-S) of APAF1 and fewer prosurvival splice variants (APAF-XL,-LC) as compared to those treated with amiloride with IR pretreatment. These observations imply that amiloride modulates radiosensitivity by regulating the alternative splicing of the APAF1 gene. A similar pattern of changes was noted in proapoptotic and prosurvival splice variants of BIRC5, but the differences were not statistically significant.

In contrast, the ratios of prosurvival splice variants of Bcl-X and HIPK3 [Bcl-XL and HIPK3 U(+)] to their respective proapoptotic variants [Bcl-XS and HIPK3 U(−); Fig. 3C] did not correlate with changes in cell survival resulting from amiloride treatment with IR post- and pretreatments (Fig. 1).

Effects of amiloride combined with pre- or post-treatment with IR on alternative splicing of APAF1 at different time points

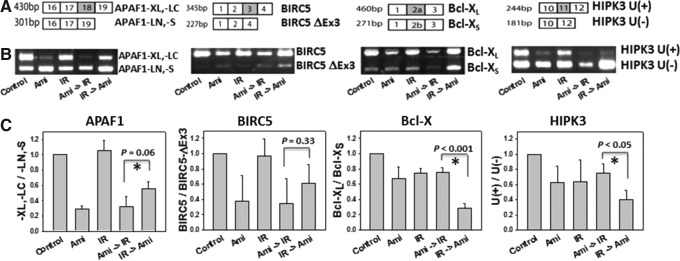

The effects of amiloride treatment performed before and after IR were further confirmed in terms of its modulation of APAF1 splicing in glioblastoma GBM8401 cells (Fig. 4A) and in human embryonic lung fibroblast control HEL 299 cells following different incubation times. In amiloride-treated GBM8401 cells incubated for 0–24 h (Fig. 4A, lanes 3–8), IR post-treatment increased proapoptotic splice variants of APAF1 (APAF1-LN, -S), but decreased prosurvival splice variants of APAF1 (APAF1-XL, -LC). Compared to amiloride-treated GBM8401 cells with IR pretreatment, those amiloride-treated GBM8401 cells with IR post-treatment had a lower ratio of prosurvival APAF1 splicing variants to proapoptotic APAF1 splice variants, indicating an increase in apoptotic cell death. In contrast, in amiloride-treated cells with IR pretreatment (Fig. 4A, lanes 9–14), the prosurvival splice variants of APAF1 (APAF1-XL, -LC) and proapoptotic splice variants of APAF1 (APAF1-LN, -S) did not substantially differ for incubation lasting from 0 to 4 h.

FIG. 4.

Expression of apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (APAF1) splicing variants after varying incubation times for GBM8401 cells treated with amiloride with IR post-treatment (amiloride→IR) or with amiloride with IR pretreatment (IR→amiloride). (A) The amiloride→IR cells were treated with 0.2 mM amiloride for 24 h, irradiated with IR 5 Gy, and then incubated in an amiloride-free medium for varying durations. The IR→amiloride cells were irradiated with IR 5 Gy and then immediately incubated with amiloride for varying durations. (B) Similar experiments were performed in human fibroblast HEL 299 cells. Lanes indicate the conditions for control, amiloride with IR pre- or post-treatments with different incubation times.

In human embryonic lung fibroblast control cells (HEL 299), amiloride combined with either IR pre- or post-treatment did not substantially change the ratios of APAF1 splicing variants (Fig. 4B, lanes 1–14). Accordingly, the different responses of tumor and embryonic fibroblast cells to the combined treatment with amiloride and IR may reflect differences in expression in APAF1 splicing variants.

Discussion

Recently, combined treatments with drugs, such as inhibitors of heat-shock protein 90 and cyclooxygenase-2, have been found to significantly enhance the therapeutic efficacy of IR (Kim and Pyo, 2012). Similarly, this study showed that amiloride treatment had an antiproliferative effect and increased radiosensitivity in irradiated GBM8401 glioblastoma cells. Earlier studies have shown that the antiproliferative effects of amiloride in several cancer cell types may result from apoptosis (Park et al., 2009; Chang et al., 2011a, 2011b). In contrast, other agents, for example, lactate and gemcitabine, are reported to, respectively, increase radioresistance (Hirschhaeuser et al., 2011) and decrease radiosensitivity (Salem et al., 2012). The current study of GBM8401 glioblastoma cells showed a larger antiproliferative effect in amiloride-treated cells with IR post-treatment compared to amiloride-treated cells with IR pretreatment. This finding supports the notion that the order of treatment with different medications can substantially affect the outcomes of anticancer therapy.

Similarly, clinical studies show that the hypoxia-activated prodrug TH-302 induces cytotoxic injury in tumors when combined with chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g., docetaxel, cisplatin, pemetrexed, irinotecan, doxorubicin, gemcitabine, or temozolomide). Interestingly, the efficacy of TH-302 is improved when administered before rather than after treatment with one of the above chemotherapeutic agents. Accordingly, when TH-302 is used in a combination with other conventional antineoplastic agents, the efficacy of TH-302 is affected by the order in which it is administered (Liu et al., 2012).

Irradiation has been reported to induce alternative splicing. For example, low-dose ultraviolet (UV) irradiation is known to regulate alternative splicing of the apoptotic gene Bcl-X in Hep3B cells (Munoz et al., 2009). Exposure to UV decreases the ratio of prosurvival/proapoptotic isoforms of Bcl-X. The current study similarly found that IR induced alternative splicing. In amiloride-treated GBM8401 glioblastoma cells, IR post-treatment activated Akt signaling and concurrently decreased the prosurvival splice variants of APAF1 (APAF1-XL,-LC). Moreover, the APAF-XL, -LC variants are prosurvival splicing variants, and the APAF1-LN, -S variants are known to have proapoptotic functions during apoptosis (Benedict et al., 2000). In GBM8401 glioblastoma cells treated with both amiloride and IR (IR pre- or post-treatment), prosurvival splice variants of APAF1 were decreased, but those of Bcl-X and HIPK3 were not. These results suggest that the discrepancy may result from different irradiation sources/dosages and cell types. Alternatively, the regulation of the splicing of Bcl-X and HIPK3 may not be involved with Akt. For example, in our previous study (Chang et al., 2011b), we found that Akt inactivation was not responsible for the splicing of Bcl-X and HIPK3 in terms of validation by PI3K inhibitor treatment in leukemic cells. In the current study, the different apoptotic radiosensitivities obtained by different orders of treatment correlated well with changes in the proapoptotic and prosurvival splicing variants of APAF1. In addition, ratios of APAF1 prosurvival/proapoptotic isoforms do not differ much between treatment with amiloride alone and amiloride followed by irradiation. The role of APAF1 splicing in the amiloride alone and the combined treatment of amiloride and irradiation needs to be further investigated.

In sum, this study found that amiloride treatment before or after IR decreased the proliferation of GBM8401 glioblastoma cells, especially in amiloride-treated cells with IR post-treatment. Combining amiloride treatment with IR has good potential for improving radiosensitivity and the efficacy of radiotherapy for human brain glioblastoma.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by grants from the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital Research Foundation (KMUH96-6G72), the Kaohsiung Medical University Research Foundation (KMUER001), the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Republic of China (Taiwan; DOH102-TD-C-111-002), NSYSU-KMU Joint Research Project (#NSYSUKMU 102-034), and the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC100-2321-B039-007 and NSC101-2320-B-037-049).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Bao S. Wu Q. McLendon R.E., et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict M.A. Hu Y. Inohara N., et al. Expression and functional analysis of Apaf-1 isoforms. Extra Wd-40 repeat is required for cytochrome c binding and regulated activation of procaspase-9. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8461–8468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratton S.B. Salvesen G.S. Regulation of the Apaf-1-caspase-9 apoptosome. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3209–3214. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull M.B. Laragh J.H. Amiloride. A potassium-sparing natriuretic agent. Circulation. 1968;37:45–53. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.37.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi A. Di Giacomo V. Rapino M., et al. Ionizing radiation induces apoptotic signal through protein kinase Cdelta (delta) and survival signal through Akt and cyclic-nucleotide response element-binding protein (CREB) in Jurkat T cells. Biol Bull. 2009;217:202–212. doi: 10.1086/BBLv217n2p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.G. Yang D.M. Chang W.H., et al. Small molecule amiloride modulates oncogenic RNA alternative splicing to devitalize human cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011a;6:e18643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W.H. Liu T.C. Yang W.K., et al. Amiloride modulates alternative splicing in leukemic cells and resensitizes Bcr-AblT315I mutant cells to imatinib. Cancer Res. 2011b;71:383–392. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.H. Chu P.M. Lee Y.J., et al. Targeting protective autophagy exacerbates UV-triggered apoptotic cell death. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:1209–1224. doi: 10.3390/ijms13011209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C.C. Chang H.W. Chuang D.W., et al. Fern plant-derived protoapigenone leads to DNA damage, apoptosis, and G(2)/m arrest in lung cancer cell line H1299. DNA Cell Biol. 2009;28:501–506. doi: 10.1089/dna.2009.0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne A.L. Price M.E. Mothersill C., et al. Relationship between clonogenic radiosensitivity, radiation-induced apoptosis and DNA damage/repair in human colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2277–2283. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedrigo C.A. Grivicich I. Schunemann D.P., et al. Radioresistance of human glioma spheroids and expression of HSP70, p53 and EGFr. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:156. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi-Chiela E.C. Villodre E.S. Zamin L.L., et al. Autophagy interplay with apoptosis and cell cycle regulation in the growth inhibiting effect of resveratrol in glioma cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y. Fan S. Liu B., et al. TCRP1 promotes radioresistance of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells via Akt signal pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;357:107–113. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0880-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhaeuser F. Sattler U.G. Mueller-Klieser W. Lactate: a metabolic key player in cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6921–6925. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holand K. Salm F. Arcaro A. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway as a therapeutic target in grade IV brain tumors. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:894–918. doi: 10.2174/156800911797264743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa K. Ishii H. Saito T. DNA damage-dependent cell cycle checkpoints and genomic stability. DNA Cell Biol. 2006;25:406–411. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.25.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.M. Pyo H. Cooperative enhancement of radiosensitivity after combined treatment of 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin and celecoxib in human lung and colon cancer cell lines. DNA Cell Biol. 2012;31:15–29. doi: 10.1089/dna.2011.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letai A. Growth factor withdrawal and apoptosis: the middle game. Mol Cell. 2006;21:728–730. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J. Slingerland J.M. Multiple roles of the PI3K/PKB (Akt) pathway in cell cycle progression. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. Sun J.D. Wang J., et al. TH-302, a hypoxia-activated prodrug with broad in vivo preclinical combination therapy efficacy: optimization of dosing regimens and schedules. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:1487–1498. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1852-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P.Z. Lai C.Y. Chan W.H. Caffeine induces cell death via activation of apoptotic signal and inactivation of survival signal in human osteoblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9:698–718. doi: 10.3390/ijms9050698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz M.J. Perez Santangelo M.S. Paronetto M.P., et al. DNA damage regulates alternative splicing through inhibition of RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell. 2009;137:708–720. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K.S. Poburko D. Wollheim C.B., et al. Amiloride derivatives induce apoptosis by depleting ER Ca(2+) stores in vascular endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:1296–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem S.D. Abou-Tarboush F.M. Saeed N.M., et al. Involvement of p53 in gemcitabine mediated cytotoxicity and radiosensitivity in breast cancer cell lines. Gene. 2012;498:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerk C. Schulze-Osthoff K. Regulation of apoptosis by alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2005;19:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura T. Acquired radioresistance of cancer and the AKT/GSK3beta/cyclin D1 overexpression cycle. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2011;52:539–544. doi: 10.1269/jrr.11098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupp R. Mason W.P. van den Bent M.J., et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiziano F.D. Neri G. Brahe C. Biomarkers in rare disorders: the experience with spinal muscular atrophy. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;12:24–38. doi: 10.3390/ijms12010024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems L. Tamburini J. Chapuis N., et al. PI3K and mTOR signaling pathways in cancer: new data on targeted therapies. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:129–138. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W. Shi C. Ma F., et al. Structural and functional characterization of two alternative splicing variants of mouse endothelial cell-specific chemotaxis regulator (ECSCR) Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:4920–4936. doi: 10.3390/ijms13044920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. Qian J. Xie X., et al. High density lipoprotein protects mesenchymal stem cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis via activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and suppression of reactive oxygen species. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:17104–17120. doi: 10.3390/ijms131217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui L. Owens K. Necrosis is not induced by gadolinium neutron capture in glioblastoma multiforme cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 2012;88:980–990. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2012.715787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen C.Y. Chiu C.C. Chang F.R., et al. 4beta-Hydroxywithanolide E from Physalis peruviana (golden berry) inhibits growth of human lung cancer cells through DNA damage, apoptosis and G2/M arrest. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]