Abstract

Cachexia is a wasting condition defined by skeletal muscle atrophy in the setting of systemic inflammation. To explore the site at which inflammatory mediators act to produce atrophy in vivo, we utilized mice with a conditional deletion of the inflammatory adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88). Although whole-body MyD88-knockout (wbMyD88KO) mice resist skeletal muscle atrophy in response to LPS, muscle-specific deletion of MyD88 is not protective. Furthermore, selective reexpression of MyD88 in the muscle of wbMyD88KO mice via electroporation fails to restore atrophy gene induction by LPS. To evaluate the role of glucocorticoids as the inflammation-induced mediator of atrophy in vivo, we generated mice with targeted deletion of the glucocorticoid receptor in muscle (mGRKO mice). Muscle-specific deletion of the glucocorticoid receptor affords a 71% protection against LPS-induced atrophy compared to control animals. Furthermore, mGRKO mice exhibit 77% less skeletal muscle atrophy than control animals in response to tumor growth. These data demonstrate that glucocorticoids are a major determinant of inflammation-induced atrophy in vivo and play a critical role in the pathogenesis of endotoxemic and cancer cachexia.—Braun, T. P., Grossberg, A. J., Krasnow, S. M., Levasseur, P. R., Szumowski, M., Zhu, X. X., Maxson, J. E., Knoll, J. G., Barnes, A. P., and Marks, D. L. Cancer- and endotoxin-induced cachexia require intact glucocorticoid signaling in skeletal muscle.

Keywords: adenocarcinoma, atrophy, inflammation, lipopolysaccharide, MyD88, sickness behavior, corticosterone

Cachexia, or disease-associated wasting, is serious complication of numerous chronic diseases. A hallmark of cachexia is a loss of skeletal muscle mass that is driven by systemic inflammation and resists conventional nutritional support (1). This is particularly problematic in cancer, in which the presence of weight loss or muscle atrophy is a powerful independent predictor of disease mortality (2, 3). It is estimated that 20% of cancer deaths are the direct result of cachexia (4). However, no effective therapy exists that can alter the progressive loss of muscle mass seen in cancer cachexia.

It is generally agreed that inflammatory cytokines play a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of cachexia via the activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (5). The muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases muscle atrophy F-box (MAFbx/atrogin-1) and muscle ring finger protein 1 (MuRF1), are highly induced in catabolic muscle and are critical for normal muscle atrophy (6, 7). These two genes are under the transcriptional regulation of the forkhead box (Foxo) family of transcription factors (8). However, the precise mechanism by which inflammation activates this catabolic pathway remains the subject of debate with in vitro and in vivo experiments producing conflicting results. In cultured myotubes, both inflammatory cytokines and the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) directly engage surface receptors on skeletal muscle driving muscle atrophy via the activation of MAFbx and MuRF1 (9–11). This process is dependent on both activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) (11, 12). In vivo, NF-κB signaling in muscle is also requisite for inflammation-induced muscle atrophy (12, 13). However, numerous neuroendocrine changes occur in response to inflammation in vivo that are not recapitulated in cultured myocytes exposed to cytokines. Inflammatory conditions, including cancer, metabolic acidosis, endotoxemia, and sepsis all result in increased levels of glucocorticoids (14–17). In the presence of similar levels of exogenously administered glucocorticoids, significant muscle atrophy is observed (18). Therefore, the relative contribution from the direct vs. systemic effects of inflammatory cytokines to the process of atrophy remains an open question.

To explore these distinct mechanisms of inflammation-induced muscle atrophy, we took advantage of the shared inflammatory adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) that is immediately downstream of both Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the type I interleukin receptor (IL-1RI). Due to its proximal position in inflammatory pathways, MyD88 signaling accurately reflects the engagement of surface receptors. In contrast, more distal pathway members, such as NF-κB, are activated by a multitude of intracellular and extracellular signals and therefore may not reflect signaling at the cell membrane. We demonstrate using a murine genetic approach that although MyD88 is requisite for inflammation-induced muscle atrophy, glucocorticoid activity via glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expressed in skeletal muscle is a critical intermediary in vivo. Further, we demonstrate that muscle wasting in an animal model of cancer is dependent on intact glucocorticoid signaling in skeletal muscle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Wild-type C57BL/6J mice, MCK-cre, MyD88 Flox, LSL-tdTomato and My88-knockout (My88KO) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). GR Flox mice were provided by L. Muglia (Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA). All animals were maintained on a normal 12:12-h light-dark cycle and provided ad libitum access to water and food (Purina rodent diet 5001; Purina Mills, St. Louis, MO, USA), except in the case of pair-fed animals, in which food intake was restricted to that consumed by the indicated group. Animals were used for experimentation between 6 and 20 wk of age, and were age, weight, and sex matched in all experiments. Mice were injected with 250 μg/kg or 1 mg/kg LPS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in normal saline with 0.5% BSA, and euthanized 8 or 18 h later. Dexamethasone (Sigma) was dissolved in peanut oil, and injected i.p. at 5 mg/kg daily for 3 d. Mice were euthanized by decapitation under anesthesia from a ketamine cocktail. Both male and female MyD88KO mice were utilized, and in all cases, they were equally represented in all experimental groups. No difference in any measures of atrophy was observed as a result of animal sex. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and they were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Oregon Health and Science University.

Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC)

LLC cells (gift from Vickie Baracos, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada) were grown in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% pen/strep. Cells (5×106) were injected subcutaneously. Tumors were grown until they achieved ∼9% of body weight, as estimated by caliper measurements, or the animals appeared moribund, at which point the animals were euthanized (average growth time of 41 d after injection). At the time of euthanasia, no metastatic lesions were observed in peritoneal or thoracic organs. No differences were observed in tumor growth or day of euthanasia between GRLox/Lox or muscle-specific GR-knockout (mGRKO) mice.

Expression vectors

The complete MyD88 cDNA was purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD, USA). The coding region of MyD88 was then amplified with the following PCR primers containing a XhoI restriction site and Kozak sequence on the 5′ primer and an EcoRI restriction site on the 3′ primer: 5′-AAAACTCGAGCGCCACCATGTCTGCGGGAGACCCC-3′ and 5′-TTTTGAATTCTCAGGGCAGGGACAAAGC-3′. MyD88 was then ligated into the pCAG plasmid containing a CAG promoter and an internal ribosome entry site–green fluorescent protein (IRES-GFP). For in vivo electroporation, plasmids were prepared by EndoFree Giga kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA).

Electroporation of skeletal muscle

Under isoflurane anesthesia, the region overlying the tibialis anterior muscle was shaved, and the muscle was injected percutaneously with 25 μl of 0.4 U/μl bovine hyaluronidase (Sigma). After 2 h, the tibialis was exposed, and 100 μg of expression plasmid in 50 μl normal saline was injected. The muscle was then electroporated using stainless-steel needle electrodes and an ECM 830 square wave pulse generator (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The following parameters were used for electroporations: 50 V/cm, 5 × 50-ms pulses with an interpulse interval of 200 ms. The incision was closed, and animals were allowed to recover for 2 wk prior to LPS treatment.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total muscle RNA was extracted with a RNeasy fibrous tissue mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was transcribed with TaqMan reverse-transcription reagents and random hexamers (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR reactions were run on an ABI 7300, with TaqMan universal PCR master mix, and TaqMan gene expression assays: mouse GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1), mouse MAFbx (Mm00499518_m1), mouse MuRF1 (Mm01185221_m1), mouse Foxo1 (Mm00490672_m1), mouse regulated in DNA damage responses 1 (REDD1; Mm00512504_g1), mouse Krüpple-like factor 15 (KLF15; Mm00517792_m1), mouse myostatin (Mstn; Mm01254559_m1), mouse BCL-2/adenovirus E1B-19kDA-interacting protein 3 (Bnip3; Mm01275600_g1), mouse cathepsin L (CstL; Mm00515597_m1), mouse GABA(A) receptor-associated protein like 1 (Gabarapl1; Mm00457880_m1), mouse NR3C1 (Mm00433832_m1) (Life Technologies). Relative expression was calculated via the ΔΔCt method and was normalized to vehicle-treated control. Statistical analysis was performed on the normally distributed ΔCt values.

PCR analysis of MyD88 recombination

Genomic DNA was isolated from a variety of tissues with a DNeasy tissue minikit (Qiagen). PCR primers that flank the LoxP sites surrounding exon 3 of the MyD88 gene were utilized: 5′-TGGACCTGGGACCTTGGGCA-3′, 5′-TACCCAGGCGGGACAGAGCC-3′. The following thermocycling program was utilized: 95°C for 45 s, 70°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s for 35 cycles.

Immunohistochemistry

Cryosections of the tibialis anterior (TA) were cut in cross section at 10 μm. Unfixed cryosections were blocked for 1 h in PBS (10 mM NaPO4 and 150 mM NaCl), 1% BSA, and 10% goat serum, and then incubated overnight in primary antibodies diluted 1:250 in PBS, 1% BSA, and 10% goat serum. The following mouse primary antibodies were used: SC-71 for myosin IIa, BF-F3 for myosin IIb, BA-D5 for myosin I (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA). Basement membrane was identified by staining with a rabbit anti-laminin antibody (Sigma). Sections were washed in PBS and incubated with the secondary antibodies diluted 1:500 in 1% BSA and 10% goat serum. The following secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 405, goat anti-mouse IgM Alexa Fluor 488, goat anti-mouse IgG2b Alexa Fluor 555, and goat anti-mouse IgG1 Alexa Fluor 633 (Life Technologies). Sections were washed in PBS and mounted with aqua-polymount (Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA). Images were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse Ti confocal fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA). Tiled images of entire sections were captured at ambient temperature and at ×200. Images were processed in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). An evenly spaced grid was placed over the section. Fiber area was measured in fibers expressing myosin IIb or myosin IIa, or in fibers lacking expression of myosin IIb, IIa, and I (type IId/x fibers) fibers at grid crossing points were measured along with all adjacent fibers of the same type. Grid size was adjusted for a given fiber type, such that ∼100 fibers were counted per section. Representative images were selected from the same anatomic region of the TA from animals representative of the group mean fiber area.

Western blotting and Pathscan antibody array

Muscles were homogenized in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA): 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM EGTA 1% Triton ×, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and supplemented with complete protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), 1 mM PMSF (Sigma), and 5 μl/ml phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II (Sigma). Samples were homogenized for 30 s with a Polytron homogenizer (Kinematica, Bohemia, NY, USA) and then were sonicated 2 × 10 s. Samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. For the Pathscan intracellular signaling array (Cell Signaling), 100 μg of protein was loaded per chamber. Slides were processed according to the manufacturer's instructions and analyzed on an Odyssey Imaging System (Li-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). Raw intensity values were normalized to the average for the vehicle-treated control, and log2 transformed to generate a normal distribution. For Western blots, 100 μg of total protein per lane was run on Criterion 4–15% gradient polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and was transferred to Immobilon PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Proteins were detected with a Lumi-Imager (Roche) and SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo, Rockford, IL, USA). The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti MyD88 (Cell Signaling) and an anti-rabbit HRP conjugate (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

In situ hybridization

Cryosections were cut at 20 μM for ISH analysis. Serial sections were cut and immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen for GFP visualization. Antisense 33P-labeled rat MAFbx riboprobe (corresponding to bases 68–413 of mouse MAFbx; 0.12 pmol/ml) was denatured, dissolved in hybridization buffer along with tRNA (1.7 mg/ml), and applied to slides. Slides were covered with glass coverslips, placed in a humid chamber, and incubated overnight at 55°C. The following day, slides were treated with RNase A and washed under conditions of increasing stringency. Slides were dipped in 100% ethanol, air dried, and then dipped in NTB-2 liquid emulsion (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA). Slides were developed 3 d later and coverslipped. Images were acquired on a Leica DM4000 B microscope, with a Leica DFC340 FX camera at ambient temperature at ×50 view using Leica Applications Suit 3.6 software (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). For visualization of GFP/mCherry in serial sections, slides were fixed in a vapor chamber with filter paper soaked in 37% formaldehyde at −20°C overnight. Slides were then postfixed in 4% PFA/PBS for 15 min, washed in PBS, and mounted with aqua-polymount (Polysciences). Fluorescent images were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse Ti confocal fluorescence microscope. Tiled images of entire sections were captured at ambient temperature and at ×200. Images were processed with ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± se. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 4.0 software (Prism Software Corp., Irvine, CA, USA). All data were analyzed with a 2-way ANOVA followed with post hoc analysis with a Bonferroni post hoc test or Student's t test as appropriate. For all analyses, significance was assigned at the level of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

MyD88 is requisite for LPS-induced muscle atrophy

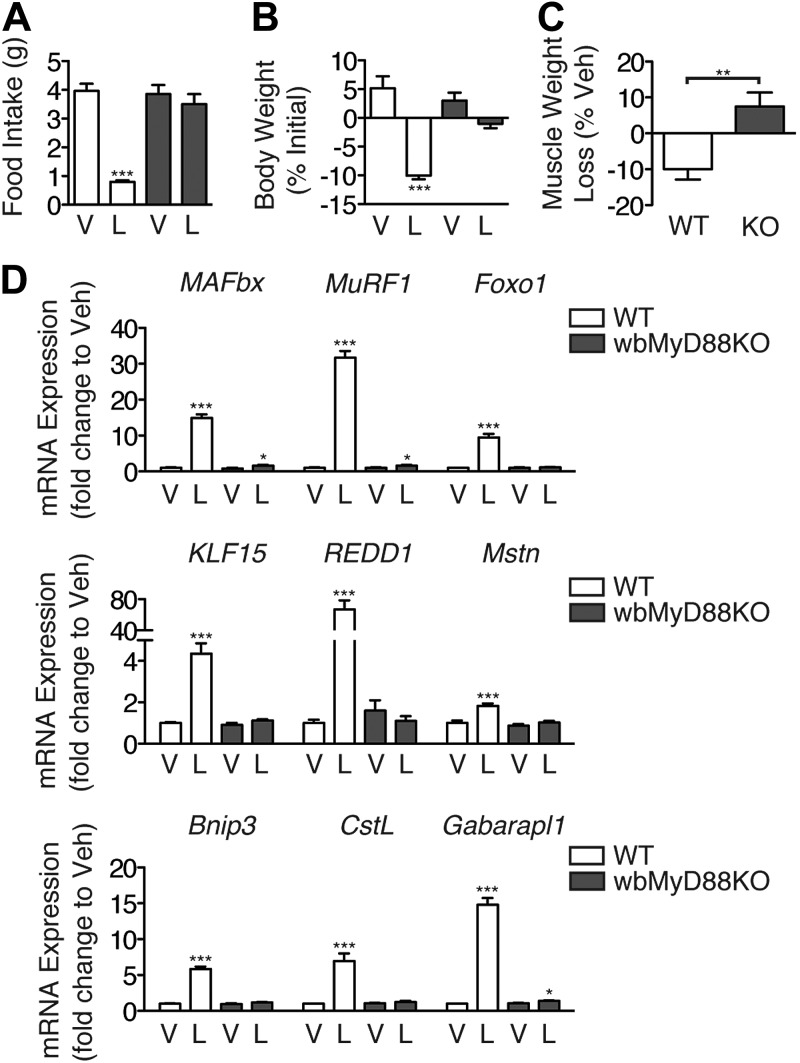

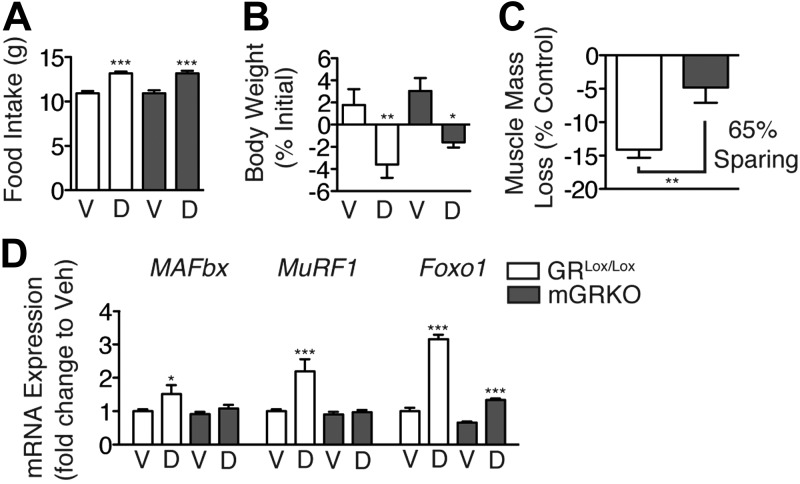

MyD88KO mice fail to show increases in circulating inflammatory cytokines after the administration of LPS and have significantly decreased mortality (19). However, alternate signaling pathways that utilize the adaptor protein TIR domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) are also capable of activating NF-κB downstream of TLR4, albeit in a delayed manner (19). While previous studies demonstrate a requirement for TLR4 in LPS-induced muscle atrophy, it is unclear whether this occurs via TRIF or MyD88 (11). To explore this, we examined the ability of LPS to produce muscle atrophy in whole-body MyD88KO (wbMyD88KO) mice. LPS (1 mg/kg) was injected immediately prior to lights out, and the animals were examined for signs of muscle atrophy. LPS produced a significant decrease in food intake in wild-type (WT) mice, but not in wbMyD88KO mice (Fig. 1A). Consistent with this, LPS also produced significant weight loss in WT but not wbMyD88KO mice (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, while LPS treatment resulted in a significant loss of muscle mass in WT mice, this effect was completely absent in wbMyD88KO mice (Fig. 1C). Skeletal muscle gene expression was measured in WT and wbMyD88KO mice after LPS administration by quantitative real time PCR. Treatment with LPS significantly induced MAFbx, MuRF1, and Foxo1 expression in the muscle of WT mice, while this effect was nearly absent in wbMyD88KO mice (Fig. 1D). LPS treatment increases the expression of the mTOR regulators KLF15 and REDD1, which would be expected to exert a negative effect on the protein synthetic rate (Fig. 1D) (20). LPS induced both genes in WT mice, but not in wbMyD88KO mice. Mstn, a secreted factor that inhibits skeletal muscle growth, plays a critical role in mediating muscle atrophy in response to a variety of stimuli and is regulated at both the transcriptional and post-translational level (21). The induction of Mstn expression in response to LPS treatment is also absent in wbMyD88KO mice (Fig. 1D). Activation of the autophagy-lysosome system also plays an important role in the atrophy process (22). Expression of the autophagy genes Bnip3, and Gabarapl1 was induced by LPS, along with the lysosomal protease CstL in WT mice. However, LPS failed to induce any of these genes in wbMyD88KO mice. Collectively, these results demonstrate that MyD88-dependent rather than MyD88-independent signaling pathways are required for LPS-induced muscle atrophy.

Figure 1.

MyD88 is required for LPS-induced muscle atrophy. WT and wbMyD88KO mice (n=5–7/group) were treated with LPS (1 mg/kg) immediately prior to lights off, and euthanized 18 h later. A, B) Food intake (A) and body weight (B) were measured. C) Gastrocnemius muscle was weighed and normalized to pretreatment body weight and presented as weight loss relative to vehicle-injected control mice of the same genotype. D) Muscle gene expression measured by quantitative real-time PCR with GAPDH as an endogenous control. V, vehicle; L, LPS; KO, wbMyD88KO. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test or t test as appropriate.

Muscle-specific deletion of MyD88 fails to prevent muscle atrophy in response to LPS

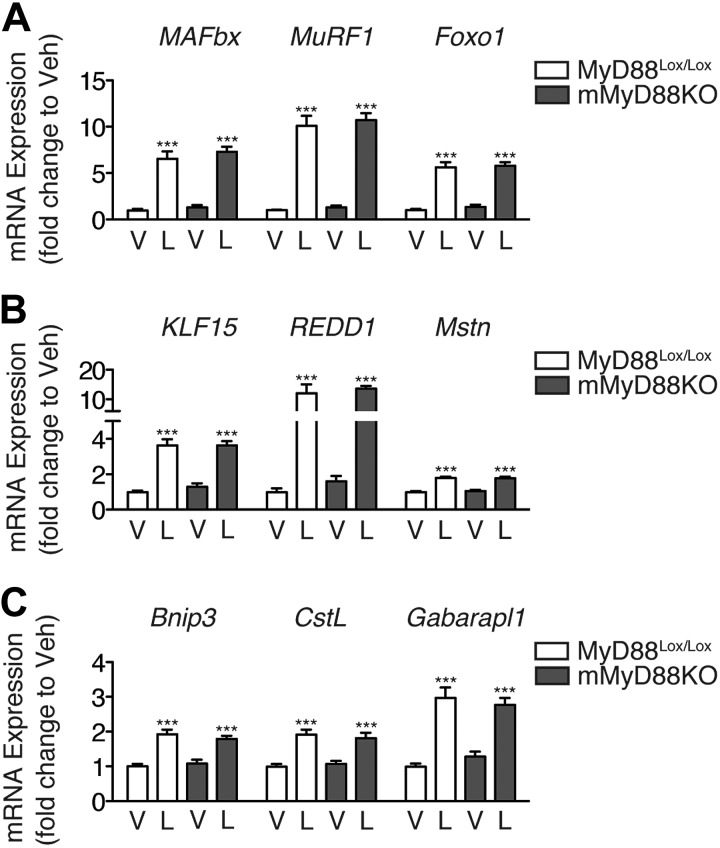

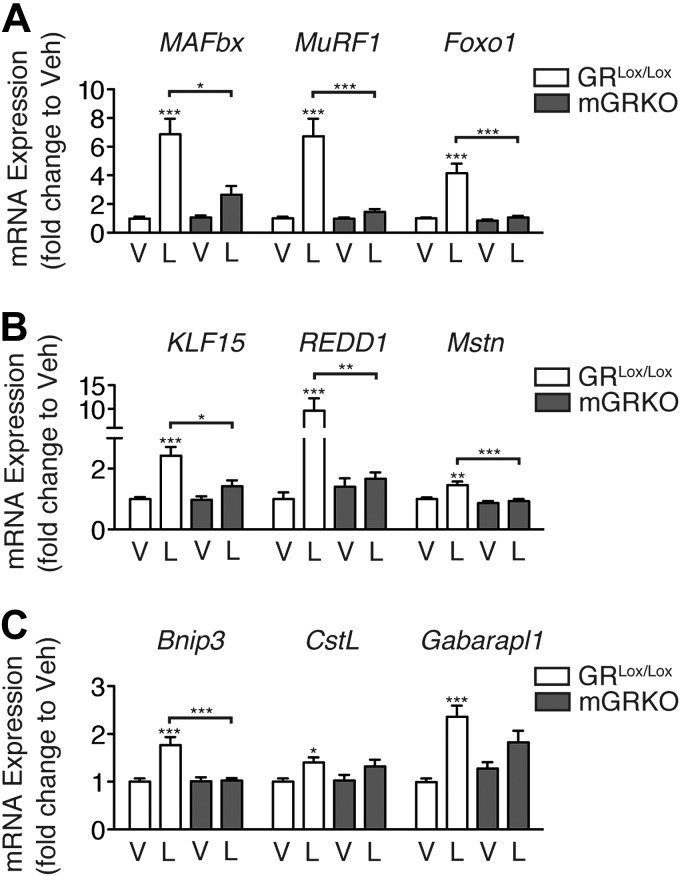

Although we have shown that MyD88 is necessary for LPS-induced muscle atrophy, the precise location at which it is required remains unclear. Skeletal muscle expresses TLR4, and this expression is required for LPS-induced atrophy in vitro (11). Therefore, a possible explanation for the lack of muscle atrophy in the MyD88KO mouse is the loss of MyD88 expression in skeletal muscle. To explore this possibility, we generated muscle-specific MyD88KO mice (mMyD88KO) mice, which demonstrate specific recombination in skeletal and cardiac muscle (Supplemental Fig. S1). To control for decreased feeding associated with LPS administration, mice were injected with LPS (250 μg/kg) at the beginning of the light cycle (when mice normally do not consume food) and were euthanized 8 h later. Muscle-specific deletion of MyD88 did not attenuate the induction of atrophy genes by LPS (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Muscle-specific deletion of MyD88 fails to prevent atrophy gene induction by LPS. Expression of MAFbx, MuRF-1, and Foxo1 (A), KLF15, REDD1, and Mstn (B), and Bnip3, CstL, and Gabarapl1 (C) in the gastrocnemius muscle of female mMyD88KO mice (n=6–10/group) 8 h after i.p. LPS injection (250 μg/kg), measured by quantitative real-time PCR using GAPDH as an endogenous control. V, vehicle, L, LPS. ***P < 0.001; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

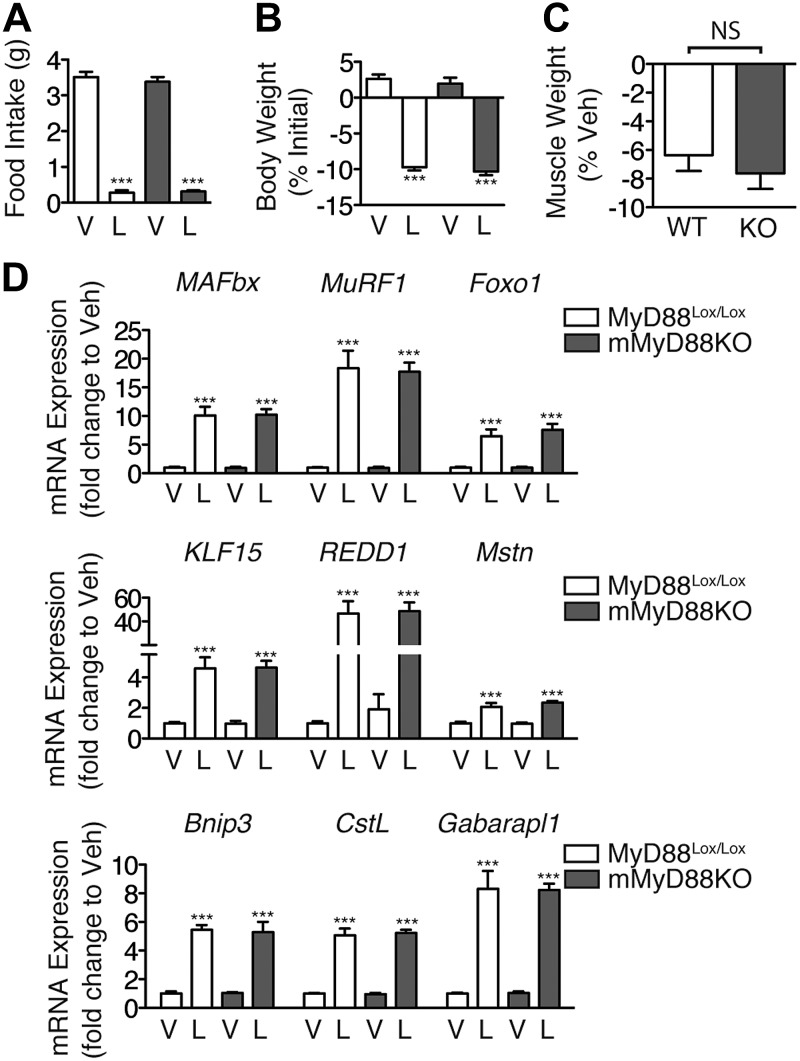

We next explored whether the loss of muscle mass in response to high-dose LPS requires MyD88 expression in skeletal muscle. A higher dose of LPS (1 mg/kg) was administered immediately before the onset of the dark cycle, and the animals were euthanized 18 h later. LPS produced an equal suppression of overnight food intake in both MyD88Lox/Lox and mMyD88KO mice (Fig. 3A). In addition, LPS produced an equivalent loss of body weight in mMyD88KO and littermate control mice (Fig. 3B, C). Finally, muscle-specific deletion of MyD88 failed to alter the induction of atrophy genes in response to high-dose LPS (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that LPS-induced muscle atrophy in vivo does not require MyD88 expression in skeletal muscle.

Figure 3.

Muscle-specific deletion of MyD88 fails to prevent muscle atrophy in response to LPS. Male mMyD88KO mice (n=7–11/group) were treated with LPS (1 mg/kg) immediately prior to lights off, and euthanized 18 h later. A, B) Food intake (A) and body weight (B) were measured. C) Gastrocnemius muscle was weighed and normalized to pretreatment body weight; results are presented as weight loss relative to vehicle-injected control mice of the same genotype. D) Muscle gene expression, measured by quantitative real-time PCR with GAPDH as an endogenous control. V, vehicle; L, LPS; KO, mMyD88KO. ***P < 0.001; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test or t test as appropriate.

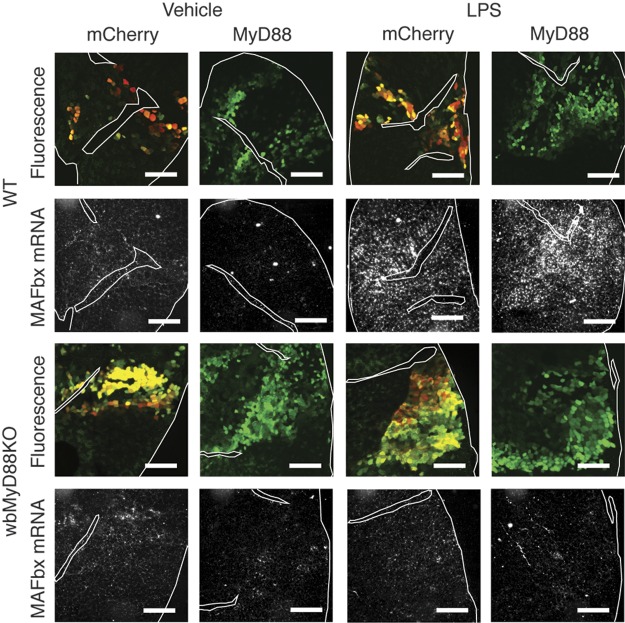

MyD88 reexpression in skeletal muscle fails to rescue LPS-mediated regulation of the MAFbx gene

The injection of LPS significantly increases the circulating levels of multiple inflammatory cytokines. Many of these are reported to induce atrophy in cultured myotubes, yet signal via pathways not involving MyD88. Our results demonstrate a requirement for MyD88 at a site distinct from skeletal muscle for LPS-induced atrophy. One possible site for this is immune cells, which, in response to LPS stimulation, may produce MyD88-independent cytokines that act on muscle to produce atrophy. To isolate the interaction of LPS with skeletal muscle, we reexpressed MyD88 selectively in the skeletal muscle of wbMyD88KO mice by electroporation (11). Transfected fibers were identified by expression of GFP via an IRES. A plasmid containing mCherry-IRES-GFP was utilized to control for the effects of electroporation. Successful overexpression of MyD88 in muscle was confirmed by Western blot (Supplemental Fig. S2). In WT mice, LPS (250 μg/kg) significantly induced MAFbx expression in skeletal muscle, as measured by in situ hybridization 8 h after injection (Fig. 4). This increase in signal was seen equally in fibers transfected with mCherry and MyD88, as well as in surrounding untransfected fibers. Overexpression of mCherry or MyD88 did not significantly induce MAFbx in muscle in the absence of LPS treatment. In wbMyD88KO mice, LPS failed to induce MAFbx mRNA in skeletal muscle. Reexpression of MyD88 by electroporation failed to rescue LPS-mediated induction of MAFbx. High-resolution images of MAFbx expression in regions of electroporation are also provided (Supplemental Fig. S2). This result shows that even when MyD88 is present exclusively in muscle, it is not sufficient for LPS-induced muscle atrophy in vivo.

Figure 4.

MyD88 signaling in muscle is not sufficient for the induction of MAFbx by LPS. Wild type (n=2/group) and wbMyD88KO (n=4/group) mice were electroporated in the TA muscle with plasmid containing mCherry-IRES-GFP or MyD88-IRES-GFP and then treated with LPS (250 μg/kg). MAFbx mRNA levels were examined by in situ hybridization in regions expressing GFP in serial sections 8 h after LPS treatment. For ease of comparison between GFP and in situ hybridization sections, connective tissue boundaries and section edges have been outlined. Scale bars = 400 μm.

Glucocorticoid signaling is required for the acute induction of catabolic genes in response to LPS

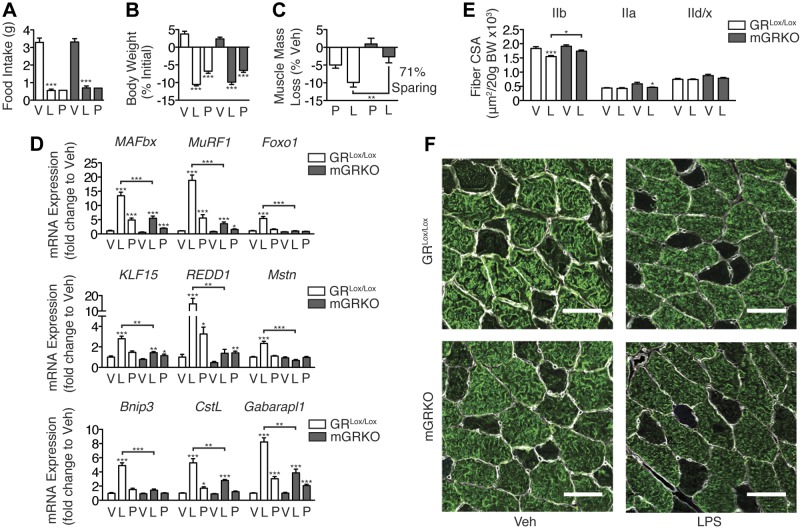

MyD88 signaling in skeletal muscle is neither necessary nor sufficient for LPS-induced muscle wasting. Therefore, as wbMyD88KO mice resist LPS-induced atrophy, it must be required at an anatomic site distinct from muscle, and the catabolic signal must be relayed to muscle indirectly. MyD88KO mice do not demonstrate a normal induction of circulating glucocorticoids and fail to activate hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in response to LPS treatment (Supplemental Fig. S3), consistent with prior results (23). To assess the role of glucocorticoid signaling in skeletal muscle while limiting the confounding effects of global glucocorticoid blockade, we generated mGRKO mice. These mice are resistant to atrophy in response to acute diabetes and starvation (24). Deletion of the GR was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR assessment of GR mRNA in muscle and by crossing the MCK-Cre driver with a tdTomato Cre reporter line (Supplemental Fig. S1). To functionally assess whether the GR had been deleted from skeletal muscle, mGRKO mice were treated for 3 d with a maximal dose of dexamethasone (5 mg/kg). Dexamethasone treatment produced equivalent increases in food intake and decreases in body weight in both GRLox and mGRKO mice (Fig. 5A, B). However, dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy was markedly attenuated in mGRKO mice, which exhibited a 65% sparing of muscle mass (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the induction of MAFbx, MuRF1, and Foxo1 by dexamethasone is blocked by muscle-specific deletion of the GR (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Muscle-specific deletion of the GR prevents muscle atrophy in response to pharmacologic dexamethasone treatment. GRLox/Lox and mGRKO mice (n=5 or 6/group) were treated for 3 d with dexamethasone (5 mg/kg). A, B) Food intake (A) and body weight (B) were measured daily. C) Gastrocnemius muscle was weighed and normalized to pretreatment body weight; results are presented as weight loss relative to vehicle-injected control mice of the same genotype. D) Gastrocnemius muscle gene expression, measured by quantitative real-time PCR with GAPDH as an endogenous control. V, vehicle; D, dexamethasone; KO, mGRKO. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test or t test as appropriate.

We examined the ability of LPS (250 μg/kg) to induce atrophy genes in the skeletal muscle of mGRKO mice. After 8 h, LPS significantly induced MAFbx, MuRF1, and Foxo1 mRNA in the skeletal muscle of littermate control mice, whereas in mGRKO mice, this effect was blocked (Fig. 6A). Correspondingly, the induction of KLF15, REDD1, and Mstn by LPS was absent in mGRKO mice (Fig. 6B), while the activation of autophagy by LPS was also attenuated in these animals (Fig. 6C). To investigate whether glucocorticoids mediate inflammation-induced myofibrillar atrophy, mGRKO mice were treated with a higher dose of LPS (1 mg/kg) and euthanized 18 h later. LPS treatment resulted in a significant decrease in food intake (controlled for by pair feeding) in both mGRKO mice and GRLox/Lox mice (Fig. 7A). LPS treatment resulted in a similar decrease in body weight in both mGRKO mice and GRlox/lox mice, while pair feeding resulted in a lesser degree of weight loss (Fig. 7B). GRLox/Lox mice lost ∼10% of their gastrocnemius muscle mass in response to LPS treatment relative to vehicle-treated controls, while mGRKO mice lost only ∼3% relative to vehicle-treated controls of the same genotype (Fig. 7C). The induction of MAFbx, MuRF1, and Foxo1 gene expression by LPS was markedly attenuated in the skeletal muscle of mGRKO mice when compared with GRLox/Lox mice (Fig. 7D). KLF15, REDD1, and Mstn gene expression was significantly induced by LPS in GRLox/Lox mice; however, this effect was nearly absent in mGRKO mice. LPS significantly induced the autophagy genes Bnip3, CstL, and Gabarapl1 in the muscle of GRLox/Lox mice. In mGRKO mice, LPS failed to induce Bnip3 and induced CstL and Gabarapl1 to a lesser extent than in GRLox/lox littermates. The cross-sectional area (CSA) of type IIb fibers (which make up the majority of murine TA muscle) was significantly reduced by LPS in GRLox/Lox mice but was reduced to a much lesser extent by LPS in mGRKO mice (Fig. 7E, F). Glucocorticoids are proposed to act via both genomic and nongenomic mechanisms to produce muscle atrophy (24, 25). Therefore, we examined a variety of signaling pathways with a Pathscan antibody array. Although an insulin-positive control stimulated significant increases in both Akt phosphorylation and ribosomal S6, LPS failed to produce significant suppression of Akt phosphorylation, or downstream signaling pathway members, such as p70S6K, GSK3β, and mTOR (Supplemental Fig. S4). This result suggests that glucocorticoid-induced atrophy in the context of acute inflammation does not occur via alterations in Akt signaling.

Figure 6.

Muscle-specific deletion of the GR prevents atrophy gene induction by LPS. Expression of MAFbx, MuRF-1, and Foxo1 (A), KLF15, REDD1, and Mstn (B), and Bnip3, CstL, and Gabarapl1 (C) in the gastrocnemius muscle of female mGRKO mice (n=6–9/group) 8 h after i.p. LPS injection (250 μg/kg), as measured by quantitative real-time PCR using GAPDH as an endogenous control. V, vehicle, L, LPS. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

Figure 7.

Muscle-specific deletion of the GR attenuates muscle atrophy in response to LPS. Male mGRKO (n=6–9/group) were treated with LPS (1 mg/kg) immediately prior to lights off, and euthanized 18 h later. A subset of vehicle-treated animals was pair fed to the LPS treatment group. A, B) Food intake (A) and body weight (B) were measured. C) Gastrocnemius muscle was weighed and normalized to pretreatment body weight and presented as weight loss relative to vehicle-injected control mice of the same genotype. D) Muscle gene expression measured by quantitative real-time PCR with GAPDH as an endogenous control. E) TA muscles were cut in cross section and immunostained with antibodies against laminin, myosin IIb, myosin IIa, and myosin I. Type IIb, IId/x (absent IIb, IIa, or I staining), and IIa fiber area was measured. F) Representative images of TA in a region of type IIb fibers (white, laminin; green, myosin IIb). Scale bars = 50 μm. V, vehicle, L, LPS, P, pair fed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

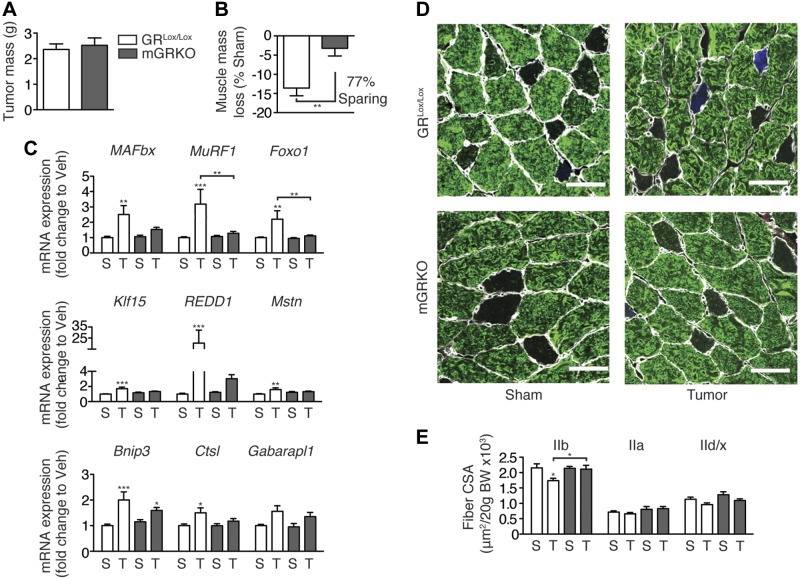

Cancer cachexia is dependent on glucocorticoid signaling in skeletal muscle

Our data demonstrate a fundamental role for glucocorticoids, rather than direct cytokine action, in endotoxin-induced muscle atrophy. To extend these observations, we explored whether glucocorticoid signaling is also required for muscle atrophy during the development of cancer cachexia. GRLox/Lox and mGRKO mice were injected with LLC cells, an established model of cancer cachexia that produces muscle wasting and inflammation (18). Tumors grew to equivalent sizes in both genotypes of mice (Fig. 8A). Tumor growth resulted in a significant loss of muscle mass in GRLox/Lox mice but not in mGRKO mice (Fig. 8B). Consistent with these observations, the induction of atrophy gene expression in response to tumor growth was blocked in mGRKO mice (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, muscle-specific deletion of the GR prevented the loss of Type IIb fiber area in response to tumor growth (Fig. 8D, E). Total tumor-free body weight was not significantly altered by tumor growth (Supplemental Fig. S4B). In total, these data establish a fundamental role for glucocorticoid signaling in skeletal muscle in the pathogenesis of cancer cachexia.

Figure 8.

Muscle-specific deletion of the GR attenuates muscle atrophy in the setting of cancer cachexia. Female GRLox/Lox and mGRKO mice (n=10–15/group) were injected with LLC cells or were sham-treated. A) Tumor mass was measured. B) Gastrocnemius muscle was weighed and normalized to pretreatment body weight; results are presented as weight loss relative to sham-treated control mice of the same genotype. C) Muscle gene expression measured by quantitative real time PCR with GAPDH as an endogenous control. D) Representative images of TA muscles that were cut in cross section and immunostained with antibodies against laminin (white) and myosin IIb (green). E) Fiber CSA of myosin IIb, IIa, and IId/x fibers normalized to initial body weight. Scale bars = 50 μm. S, sham, T, tumor. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs. sham-treated mice of the same genotype; t test or 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test as appropriate.

DISCUSSION

Inflammation is a fundamental mediator of muscle atrophy in numerous chronic diseases, including cancer. However, the site at which inflammation acts to produce muscle atrophy has previously been incompletely described. In vitro, cytokines act in a cell-autonomous manner to induce the atrophy of cultured myotubes (9–11, 27). Consistent with this, in vivo studies demonstrated a requirement for NF-κB specifically in skeletal muscle for normal atrophy in response to inflammation (12). However, recombinant cytokines failed to increase protein degradation in muscle explants bringing into question the generalizability of this mechanism (28). Inflammation also has significant impacts on multiple circulating hormones, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) and glucocorticoids, the net effect of which would be to further promote the loss of muscle mass. Complicating this issue further is the nodal nature of NF-κB as a common effector of multiple signaling pathways. While NF-κB can be activated in response to cytokine signaling at the cell surface, many other intracellular stress pathways also converge on NF-κB. In response to unloading or denervation (conditions not typically associated with systemic inflammation), NF-κB signaling is increased and blockade of NF-κB signaling in muscle prevents atrophy in either of these states (12, 26). Therefore, it is unclear to what degree NF-κB loss-of-function studies provide evidence for direct cytokine action on skeletal muscle as the mechanism for inflammation-induced atrophy in vivo.

To resolve this issue, we utilized MyD88 loss-of-function to assess the contribution of TLR and IL-1RI signaling to muscle atrophy in response to systemic inflammation. We found that despite MyD88 being required for muscle atrophy in response to LPS, muscle-specific deletion of MyD88 failed to alter LPS-induced atrophy. Instead, MyD88 is required for the release of glucocorticoids in response to inflammation, which subsequently convey a majority of the catabolic signal to muscle. This likely occurs via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, although the present work cannot exclude effects at the level of pituitary and/or adrenal gland. In addition, the resistance of mGRKO mice to cancer cachexia extends these findings to a clinically relevant disease model. These results demonstrate that a major component of muscle atrophy in response to inflammation in vivo is the result of inflammatory signaling in the brain, not in skeletal muscle.

These findings are somewhat surprising, given the extensive literature demonstrating the direct effects of inflammatory mediators on skeletal muscle metabolism. In particular, both IL-1β and LPS are sufficient to induce atrophy in cultured myotubes (10, 11). A possible explanation for this is that MyD88-independent signaling pathways are responsible for LPS-induced atrophy. Indeed, in vitro, LPS still activates NF-κB in MyD88-deficient cells, albeit in a delayed manner (19). Furthermore, the direct action of LPS on cultured myotubes requires both TLR4 and p38 MAPK (11). LPS activates p38 MAPK signaling in MyD88-deficient macrophages in vitro, although again with slower kinetics (19). An alternate explanation for our findings is that LPS potently induces circulating TNF and IL-6, which are both sufficient to induce muscle atrophy in vitro. Unlike IL-1β and LPS however, TNF and IL-6 do not signal via MyD88. In the mMyD88KO, LPS may signal in a MyD88-dependent manner in immune cells, triggering TNF and IL-6 production that subsequently act on skeletal muscle to produce atrophy. Our data, however, show that neither of these possibilities is likely to be the case.

The finding that wbMyD88KO mice fail to demonstrate muscle atrophy in response to LPS argues that the MyD88-independent pathway is dispensable for this process in vivo. Suggesting that circulating TNF and IL-6 are not responsible for LPS-induced muscle atrophy is our observation that although neither mGRKO nor mMyD88KO mice exhibit recombination in immune cells, only the latter displays significant atrophy. Correspondingly, intact adrenals are required for protein degradation in response to recombinant TNF in vivo (29, 30). Further raising doubt about the ability of LPS to directly act on muscle to produce atrophy, MyD88 reexpression in the skeletal muscle of wbMyD88KO mice fails to rescue LPS-mediated induction of MAFbx expression. This occurs despite the fact that LPS accumulates in skeletal muscle to a significant degree after parenteral administration (11, 31). Therefore, while the direct action of cytokines and LPS on cultured myotubes produces atrophy under culture conditions, our findings do not support this as a major mechanism of atrophy in vivo.

Glucocorticoids play a role in acute changes in protein turnover, resulting from a variety of conditions. Adrenalectomized animals or pharmacologic antagonism of the GR has been used in studies that show that atrophy in response to acute sepsis, starvation, metabolic acidosis, and diabetes depend to some degree on glucocorticoid signaling (14, 32–34). However, this approach is complicated in the setting of inflammation. Adrenalectomized mice display a 1000-fold decrease in the LD50 of endotoxin (35), likely due to a combination of cardiovascular instability and a loss of anti-inflammatory feedback from glucocorticoids. Early studies examining the mechanisms of cytokine-induced protein degradation found that concurrent cytokine administration and glucocorticoid antagonism resulted in significant mortality (29). Therefore, experiments examining the necessity of glucocorticoids for inflammation-induced atrophy have produced conflicting results (29, 36). Deleting the GR specifically from skeletal muscle allows for the clarification of the contribution of glucocorticoid signaling to inflammation-induced muscle atrophy without the complication of complete adrenal insufficiency. While it is clear that glucocorticoids are integral to inflammatory atrophy, this may occur in synergy with the direct action of inflammatory cytokines. However, our recent data suggests that the levels of circulating glucocorticoids evoked by inflammatory challenge are sufficient to produce substantial atrophy in isolation (18).

The role of glucocorticoids in cancer cachexia has been the subject of several previous studies (37, 38). Two such studies utilized the glucocorticoid antagonist RU38486 in models of cancer cachexia. However, in addition to having numerous effects in nonmuscle tissue, RU38486 has only a 2 h half-life in rodents (39). Consistent with this, GR blockade by RU38486 declines rapidly after RU38486 administration. As a result, RU38486 only results in a ∼30% protection of skeletal muscle mass in response to dexamethasone administration. Neither tumor study demonstrated a significant protection of muscle mass by RU38486, but these studies did not have the statistical power to detect a 30% reduction in muscle wasting. A third study examined muscle wasting in tumor-bearing adrenalectomized rats (40). Unfortunately, no adrenalectomized control animals were used, as adrenalectomy exerts negative effects on body weight (41). Despite this, a trend toward increased muscle mass was observed in adrenalectomized, tumor-bearing rats. By using a genetic approach, we have overcome the confounders associated with the pharmacology of glucocorticoid antagonism, as well as the systemic effects of global glucocorticoid deficiency. Our findings here are the first to demonstrate a role for glucocorticoids in the development of cachexia in a murine cancer model. Future studies will likely explore the generalizability of these findings to other models of cancer cachexia and to the development of cachexia in human patients with cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants DK-70333 and DK-084646, Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant 200948, the Rubinstein Radiation Research Scholarship, and the Portland Achievement Awards for College (ARCS) chapter.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- Bnip3

- BCL-2/adenovirus E1B-19kDA-interacting protein 3

- CSA

- cross-sectional area

- CstL

- cathepsin L

- Foxo

- forkhead box

- Gabarapl1

- GABA(A) receptor-associated protein like 1

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- IL-1RI

- type I interleukin-1 receptor

- IRES

- internal ribosome entry site

- KLF15

- Krüpple-like factor 15

- LLC

- Lewis lung carcinoma

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- MAFbx

- muscle atrophy F-box

- mGRKO

- muscle-specific glucocorticoid receptor knockout

- mMyD88KO

- muscle-specific whole-body myeloid differentiation factor 88 knockout

- Mstn

- myostatin

- MuRF-1

- muscle ring finger protein 1

- MyD88

- myeloid differentiation factor 88

- MyD88KO

- myeloid differentiation factor 88 knockout

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- p38 MAPK

- p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

- REDD1

- regulated in DNA damage responses 1

- TA

- tibialis anterior

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- TRIF

- TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β

- wbMyD88KO

- whole-body myeloid differentiation factor 88 knockout

- WT

- wild type

REFERENCES

- 1. Evans W. K., Makuch R., Clamon G. H., Feld R., Weiner R. S., Moran E., Blum R., Shepherd F. A., Jeejeebhoy K. N., DeWys W. D. (1985) Limited impact of total parenteral nutrition on nutritional status during treatment for small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 45, 3347–3353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeWys W. D. (1986) Weight loss and nutritional abnormalities in cancer patients: incidence, severity and significance. Clinics Oncol. 5, 251–261 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tan B. H., Birdsell L. A., Martin L., Baracos V. E., Fearon K. C. (2009) Sarcopenia in an overweight or obese patient is an adverse prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 6973–6979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tisdale M. J. (2002) Cachexia in cancer patients. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 862–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baracos V. E., DeVivo C., Hoyle D. H., Goldberg A. L. (1995) Activation of the ATP-ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in skeletal muscle of cachectic rats bearing a hepatoma. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. Physiol. 268, E996–E1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodine S. C., Latres E., Baumhueter S., Lai V. K., Nunez L, Clarke B. A., Poueymirou W. T., Panaro F. J., Na E., Dharmarajan K., Pan Z. Q., Valenzuela D. M., DeChiara T. M., Stitt T. N., Yancopoulos G. D., Glass D. J. (2001) Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 294, 1704–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gomes M. D., Lecker S. H., Jagoe R. T., Navon A., Goldberg A. L. (2001) Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 14440–14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sandri M., Sandri C., Gilbert A., Skurk C., Calabria E., Picard A., Walsh K., Schiaffino S., Lecker S. H., Goldberg A. L. (2004) Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 117, 399–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Acharyya S., Ladner K. J., Nelsen L. L., Damrauer J., Reiser P. J., Swoap S., Guttridge D. C. (2004) Cancer cachexia is regulated by selective targeting of skeletal muscle gene products. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 370–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li W., Moylan J. S., Chambers M. A., Smith J., Reid M. B. (2009) Interleukin-1 stimulates catabolism in C2C12 myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 297, C706–C714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doyle A., Zhang G., Abdel Fattah E. A., Eissa N. T., Li Y.-P. (2011) Toll-like receptor 4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced muscle catabolism via coordinate activation of ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome pathways. FASEB J. 25, 99–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cai D., Frantz J. D., Tawa N. E., Melendez P. A., Oh B.-C., Lidov H. G. W., Hasselgren P.-O., Frontera W. R., Lee J. D., Glass J., Shoelson S. E. (2004) IKKβ/NF-κB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell 119, 285–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paul P. K., Gupta S. K., Bhatnagar S., Panguluri S. K., Darnay B. G., Choi Y., Kumar A. (2010) Targeted ablation of TRAF6 inhibits skeletal muscle wasting in mice. J. Cell Biol. 191, 1395–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitch W. E., Medina R., Grieber S., May R. C., England B. K., Price S. R., Bailey J. L., Goldberg A. L. (1994) Metabolic acidosis stimulates muscle protein degradation by activating the adenosine triphosphate-dependent pathway involving ubiquitin and proteasomes. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 2127–2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tiao G., Lieberman M., Fischer J. E., Hasselgren P. O. (1997) Intracellular regulation of protein degradation during sepsis is different in fast- and slow-twitch muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 272, R849–R856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tanaka Y., Eda H., Tanaka T., Udagawa T., Ishikawa T., Horii I., Ishitsuka H., Kataoka T., Taguchi T. (1990) Experimental cancer cachexia induced by transplantable colon 26 adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Res. 50, 2290–2295 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elander L., Engström L., Ruud J., Mackerlova L., Jakobsson P.-J., Engblom D., Nilsberth C., Blomqvist A. (2009) Inducible prostaglandin E2 synthesis interacts in a temporally supplementary sequence with constitutive prostaglandin-synthesizing enzymes in creating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to immune challenge. J. Neurosci. 29, 1404–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braun T. P., Zhu X., Szumowski M., Scott G. D., Grossberg A. J., Levasseur P. R., Graham K., Khan S., Damaraju S., Colmers W. F., Baracos V. E., Marks D. L. (2011) Central nervous system inflammation induces muscle atrophy via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J. Exp. Med. 208, 2449–2463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawai T., Adachi O., Ogawa T., Takeda K., Akira S. (1999) Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity 11, 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shimizu N., Yoshikawa N., Ito N., Maruyama T., Suzuki Y., Takeda S.-I., Nakae J., Tagata Y., Nishitani S., Takehana K., Sano M., Fukuda K., Suematsu M., Morimoto C., Tanaka H. (2011) Crosstalk between glucocorticoid receptor and nutritional sensor mTOR in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 13, 170–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gilson H., Schakman O., Combaret L., Lause P., Grobet L., Attaix D., Ketelslegers J. M., Thissen J. P. (2007) Myostatin gene deletion prevents glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy. Endocrinology 148, 452–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mammucari C., Milan G., Romanello V., Masiero E., Rudolf R., Del Piccolo P., Burden S. J., Di, Lisi R., Sandri C., Zhao J., Goldberg A. L., Schiaffino S., Sandri M. (2007) FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 6, 458–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ogimoto K., Harris M. K, Jr., Wisse B. E. (2006) MyD88 is a key mediator of anorexia, but not weight loss, induced by lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-1 beta. Endocrinology 147, 4445–4453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu Z., Wang H., Lee I. H., Du J., Mitch W. E. (2009) Endogenous glucocorticoids and impaired insulin signaling are both required to stimulate muscle wasting under pathophysiological conditions in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 3059–3069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Watson M. L., Baehr L. M., Reichardt H. M., Tuckermann J. P., Bodine S. C., Furlow J. D. (2012) A cell-autonomous role for the glucocorticoid receptor in skeletal muscle atrophy induced by systemic glucocorticoid exposure. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 302, E1210–E1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Gammeren D., Damrauer J. S., Jackman R. W., Kandarian S. C. (2008) The IκB kinases IKKα and IKKβ are necessary and sufficient for skeletal muscle atrophy. FASEB J. 23, 362–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Y.-P., Chen Y., John J., Moylan J., Jin B., Mann D. L., Reid M. B. (2005) TNF-α acts via p38 MAPK to stimulate expression of the ubiquitin ligase atrogin1/MAFbx in skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 19, 362–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goldberg A. L., Kettelhut I. C., Furuno K., Fagan J. M., Baracos V. (1988) Activation of protein breakdown and prostaglandin E2 production in rat skeletal muscle in fever is signaled by a macrophage product distinct from interleukin 1 or other known monokines, J. Clin. Invest. 81, 1378–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zamir O., Hasselgren P. O., Higashiguchi T., Frederick J. A., Fischer J. E. (1992) Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) induce muscle proteolysis through different mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. 1, 247–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mealy K., van Lanschot J. J., Robinson B. G., Rounds J., Wilmore D. W. (1990) Are the catabolic effects of tumor necrosis factor mediated by glucocorticoids? Arch. Surg. 125, 42–47, discussion 47–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mathison J. C., Ulevitch R. J., Fletcher J. R., Cochrane C. G. (1980) The distribution of lipopolysaccharide in normocomplementemic and C3-depleted rabbits and rhesus monkeys. Am. J. Pathol. 101, 245–264 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tiao G., Fagan J., Roegner V., Lieberman M., Wang J. J., Fischer J. E., Hasselgren P. O. (1996) Energy-ubiquitin-dependent muscle proteolysis during sepsis in rats is regulated by glucocorticoids. J. Clin. Invest. 97, 339–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wing S. S., Goldberg A. L. (1993) Glucocorticoids activate the ATP-ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system in skeletal muscle during fasting. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrionol. Metab. 264, E668–E676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. May R. C., Kelly R. A., Mitch W. E. (1986) Metabolic acidosis stimulates protein degradation in rat muscle by a glucocorticoid-dependent mechanism. J. Clin. Invest. 77, 614–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Masferrer J. L., Seibert K., Zweifel B., Needleman P. (1992) Endogenous glucocorticoids regulate an inducible cyclooxygenase enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89, 3917–3921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zamir O., Hasselgren P. O., von Allmen D., Fischer J. E. (1993) In vivo administration of interleukin-1 alpha induces muscle proteolysis in normal and adrenalectomized rats. Metab. Clin. Exp. 42, 204–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rivadeneira D. E., Naama H. A., McCarter M. D., Fujita J., Evoy D., Mackrell P., Daly J. M. (1999) Glucocorticoid blockade does not abrogate tumor-induced cachexia. Nutr. Cancer 35, 202–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Llovera M., García-Martínez C., Costelli P., Agell N., Carbó N., López-Soriano F. J., Argilés J. M. (1996) Muscle hypercatabolism during cancer cachexia is not reversed by the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU38486. Cancer Lett 99, 7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heikinheimo O., Pesonen U., Huupponen R., Koulu M., Lähteenmäki P. (1994) Hepatic metabolism and distribution of mifepristone and its metabolites in rats. Hum. Reprod. 9(Suppl. 1), 40–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tessitore L., Costelli P., Baccino F. M. (1994) Pharmacological interference with tissue hypercatabolism in tumour-bearing rats. Biochem. J. 299, 71–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gosselin C., Cabanac M. (1997) Adrenalectomy lowers the body weight set-point in rats. Physiol. Behav. 62, 519–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.