Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is characterized by osteolytic bone lesions with uncoupled bone remodeling. In this study, we examined the effects of adenosine and its receptors (A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R) on osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation of cells derived from patients with MM and healthy control subjects. Mesenchymal stem cells and bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells were isolated from bone marrow and differentiated into osteoblasts and osteoclasts, respectively. A1R antagonist rolofylline and A2BR agonist BAY60-6583 inhibit osteoclast differentiation of cells from patients with MM in a dose-dependent manner, as shown by TRAP staining (IC50: 10 and ∼10 nM, respectively). BAY60-6583 and dipyridamole, a nucleoside transport inhibitor, stimulate osteoblast differentiation of cells from patients with MM, as measured by ALP activity at d 14 and Alizarin Red staining at d 21 (by 1.57±0.03- and 1.71±0.45-fold, respectively), which can be blocked by A2BR antagonist MRS1754. Consistently, real-time PCR showed a significant increase of mRNA of osteocalcin and osterix at d 14. The effect of adenosine and its receptors is consistent in patients with MM and healthy subjects, suggesting an intrinsic mechanism that is important in both MM bone metabolism and normal physiology. Furthermore, the effect of dipyridamole on osteoblast differentiation is diminished in both A2BR- and CD39-knockout mice. These results indicate that adenosine receptors may be useful targets for the treatment of MM-induced bone disease.—He, W., Mazumder, A., Wilder, T., Cronstein. B. N. Adenosine regulates bone metabolism via A1, A2A, and A2B receptors in bone marrow cells from normal humans and patients with multiple myeloma.

Keywords: osteoclast differentiation, osteoblast differentiation, osteolytic bone disease

Each year there are >20,000 cases of multiple myeloma (MM) diagnosed in the United States. One important clinical manifestation of MM is osteolytic bone lesions that can cause pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, hypercalcemia, and severe bone pain. About 80% of patients with MM develop lytic bone lesions (1), and 40–60% of patients have pathological fractures over the course of their disease (2–4). Pathological fracture of bone contributes to >20% of MM patient death (2, 3). Although recent therapeutic advances prolong patients' survival, the disease remains incurable, and relapse is inevitable. Histological studies have shown that in patients with MM with osteolytic lesions, the balance between osteoclast and osteoblast function is severely disrupted, with enhanced osteoclastic bone destruction accompanied by suppressed osteoblastic bone formation adjacent to MM cells (5–7). It is believed that the bone marrow microenvironment plays a key role in the bone destructive process. Infiltrated myeloma cells stimulate osteoclast differentiation and increase bone resorption activity by the production of cytokines and local factors, including interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and MIP-1β, and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) (8–10). At the same time, malignant plasma cells inhibit osteoblast differentiation by direct cell-to-cell contact and cytokine secretion. These include adhesion molecule VLA-4 and Wnt signaling inhibitors: soluble-frizzled related protein-2 (sFRP2) and DKK1 (11–13). Thus, new therapeutics aimed at restoring bone homeostasis may lead to a better outcome in MM.

Recent studies from our group and others suggest that adenosine, a purine nucleoside released from hypoxic or injured tissues and tumors, modulates the differentiation and function of osteoclasts and osteoblasts in vitro and in vivo, via interaction with ≥1 of 4 adenosine receptors (A1R, A2AR, A2BR, or A3R; refs. 14–22). With the exception of A2AR, our prior studies and most other studies of adenosine receptor-mediated regulation of bone homeostasis have been carried out in normal murine marrow-derived precursors or cultured cell lines, whereas little is known about the role of adenosine receptor regulation of normal human bone cells. In particular, the potential role of adenosine and its receptors in the pathogenesis of myeloma bone disease has not been explored. In the present study, we examined the effects of all 4 adenosine receptors in regulation of osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation of bone marrow derived from normal human and patients with MM. Blockade of A1R and activation of A2AR and A2BR inhibits osteoclast formation but, interestingly, A2BR, not A2AR, appears to stimulate human osteoblast formation. The other important finding from current study is that the regulation of adenosine and its receptors in bone remodeling is consistent in healthy individuals and patients with MM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and reagents

A2B-knockout mice were kindly provided by Dr. Michael Blackburn (University of Texas, Houston, TX, USA) and ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (ENTPD1; CD39)-knockout mice were kindly provided by Dr. Simon Robson (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA). They were both bred onto C57BL/6 background (>10 backcrosses) in the New York University School of Medicine Animal Facility. All experimental mice of C57BL/6 wild type, A2B knockout, and CD39 knockout were 6- to 8-wk-old female mice. All experimental procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the School of Medicine of New York University. Rolofylline (K3769), MRS 1191 (M227), and dipyridamole (D9766) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). CGS 21680 (no. 1063), ZM 241385 (1036), IB-MECA (1066), and MRS 1754 (2752) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). BAY 60–6583 was a generous gift from Bayer HealthCare (Tarrytown, NY, USA). Recombinant human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and RANKL were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Dexamethasone, ascorbic acid, and β-glycerophosphate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Primary human osteoclast and osteoblast cultures

For generation of bone marrow-derived human osteoclasts, mononuclear cells were isolated with the Ficoll-Paque density gradient separation method (Histopaque 1077; Sigma-Aldrich) from either unprocessed fresh human bone marrow (1M-105; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) or bone marrow aspirates collected from patients with MM. Briefly, bone marrow aspirate (∼7 ml) was diluted 1:2 in PBS (v/v), layered over a Ficoll-Paque density gradient, and centrifuged at 400 g for 30 min at room temperature. Mononuclear cells were washed, counted with a hemocytometer, and seeded in culture dishes at 1 × 105 cell/cm2 density. Mononuclear cells were cultured with recombinant human M-CSF (30 ng/ml) for 2 d. Cells at this stage were considered M-CSF-dependent bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) and used as osteoclast precursors. Induction of differentiation to osteoclasts was achieved by culturing the BMM cells with the osteoclastogenic medium containing human M-CSF (30 ng/ml) and recombinant human RANKL (30 ng/ml). To test the effect of adenosine and its receptors on osteoclastogenesis, different doses of adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists were supplemented to the osteoclastogenic medium for 7 d. Mononuclear cells were isolated from fresh bone marrow of myeloma patients as described above. Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were isolated by culturing mononuclear cells in culture dishes for 5 d. Adherent BMSCs were then cultured at 5 × 104 cells/cm2 with osteogenic medium containing 1 μM dexamethasone, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate. To test the effect of adenosine and its receptors on osteogenesis, different doses of adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists were supplemented to the osteogenetic medium for 14 d for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity assay, or for 21 d for Alizarin Red staining. Bone marrow aspirates were obtained from patients with MM after informed consent. All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of New York University School of Medicine.

Primary mouse osteoblast culture

For generation of mouse bone marrow-derived osteoblasts, bone marrow cells from 6- to 8-wk-old female mice were isolated as described previously (17). Briefly, bone marrow was extracted from femora and tibia of mice and cultured in 100-mm culture dishes for 3 d. The adherent cells were washed and cultured till confluency. The stromal cells were then washed and counted with a hemocytometer and reseeded in culture dishes at 1 × 105 cell/cm2 density with osteogenic medium. To test the effect of adenosine and its receptors on osteogenesis, different doses of adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists were supplemented to the osteogenetic medium for 4 d for ALP activity assay, or for 10 d for Alizarin Red staining.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining

Osteoclast differentiation was evaluated by staining for TRAP using a leukocyte acid phosphatase kit (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously (16). TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (≥3 nuclei) were counted as osteoclasts.

Alizarin Red staining

Measurement of osteoblast-mediated mineralization was detected in fixed cultures by staining with 2% Alizarin Red.

ALP activity assay

ALP activity of osteoblasts was measured with a colorimetric enzyme kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The amount of p-nitrophenol released by the enzyme reaction was determined by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm using a microplate reader. The enzyme activity was recorded as nmol/104 cells.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from culture cells using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as described previously (16). Briefly, cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a volume of 20 μl. Real-time PCR was performed using Master SYBR Green Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Primer sequences were as follows: hβ-actin, forward 5′-GCGAGAAGATGACCCAGATC-3′, reverse 5′-CGGAGTCCATCACGATGCCA-3′; hOsteocalcin. forward 5′-ATGAGAGCCCTCACACTCCTC-3′, reverse. 5′-CGTAGAAGCGCCGATAGGC-3′; hOsterix, forward, 5′-TAGTGGTTTGGGGTTTGTTTTACCGC-3′, reverse 5′-AACCAACTCACTCTTATTCCCTAAGT-3′. PCR conditions were 95°C for 5 min followed by 38 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Each experiment was done in triplicate, and results were standardized against the message level of β-actin. The comparative CT method was used to calculate the expression levels of RNA transcripts.

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as means ± sd from ≥3 independent experiments using cells from different mice. Statistical analysis was performed by use of Prism 4.02 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All data were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc testing. Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

A1R antagonist rolofylline or A2BR agonist Bay 60–6583 inhibits human osteoclast formation by bone marrow precursors

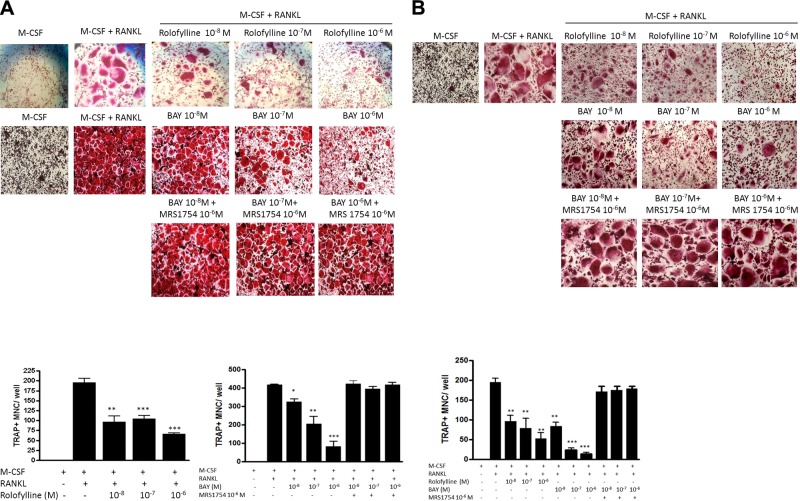

Consistent with our prior observations in mice (17, 18), blockade of A1R with the A1R-selective antagonist rolofylline suppressed M-CSF/RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation of bone marrow cells (TRAP+ cells with >3 nuclei) from both patients with myeloma (Fig. 1A) and healthy subjects (Fig. 1B) in a dose-dependent manner (IC50<10 nM for both). In line with our previous report that the A2BR agonist Bay 60–6583 inhibits mouse osteoclast differentiation (16), stimulation of A2BRs inhibited osteoclast differentiation of bone marrow precursors from patients with myeloma and healthy subjects with an IC50 of ∼100 nM (Fig. 1A) and 10 nM (Fig. 1B), respectively. Treatment with the A2BR antagonist MRS1754 (1 μM) completely reversed the inhibitory effects of A2BR agonist Bay 60–6583 on osteoclast differentiation of BMMs derived from patients with myeloma (Fig. 1A) and healthy subjects (Fig. 1B). In addition, we have previously reported that A2AR stimulation inhibits osteoclast differentiation of BMMs derived from patients with myeloma and healthy individuals (14). With the exception of A3R, whose agonist (0.1–10 μM IB-MECA) and antagonist (0.1–10 μM MRS 1191) have no effect on osteoclast differentiation (data not shown), adenosine acts at 3 of its receptors (A1R, A2AR, and A2BR) to regulate human osteoclast differentiation.

Figure 1.

Suppression of human osteoclast formation from bone marrow precursors by A1R-selective antagonist rolofylline or A2BR agonist Bay 60–6583. Human BMMs derived from patients with MM (A) or healthy control subjects (B) were cultured with hM-CSF and hRANKL (30 ng/ml each), with or without various concentrations of rolofylline or Bay 60–6583 or 1 μM MRS 1754 for 7 d in 48-well plates for TRAP staining (top panels). Numbers of TRAP-positive multinuclear cells containing >3 nuclei (TRAP+ MNC) were counted (bottom panels). Values are shown as means ± sd of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. RANKL + M-CSF cells.

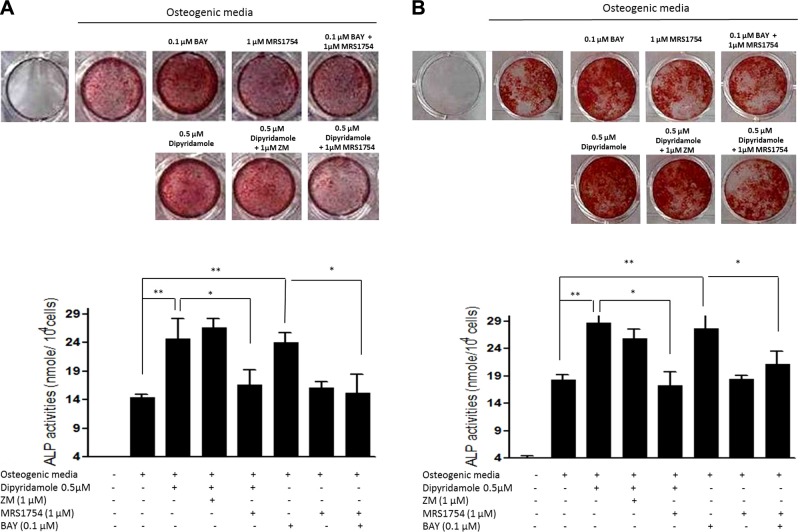

Direct A2B stimulation, as well as treatment with the nucleoside transport inhibitor dipyridamole, enhances osteoblastic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) cultures via A2BR

Recent studies in cell lines and murine cells indicate that adenosine enhances osteoblast differentiation mainly through A2BR (19, 20). In confirmation of these findings, Alizarin Red staining for matrix mineralization at d 21, coupled with ALP activity assay at d 14, showed that the A2BR agonist Bay 60–6583 stimulates osteoblast differentiation of MSCs derived from patients with myeloma and healthy individuals by 1.57 ± 0.03-fold (Fig. 2A) and 1.38 ± 0.11-fold (Fig. 2B), respectively, an effect that was completely reversed by the A2B antagonist MRS 1754. Stimulation or blockade of A1R (agonist CPA, 0.1–10 μM; antagonist rolofylline, 0.01–1 μM), A2AR (agonist CGS 21680, 0.1–10 μM; antagonist ZM 241385, 0.1–10 μM), and A3R (agonist IB-MECA, 0.1–10 μM; antagonist MRS 1191, 0.1–10 μM) has no effect on human osteoblast differentiation (data not shown). Because many cells release adenosine, which can act in an autocrine fashion, we next determined whether the nucleoside transport inhibitor dipyridamole, which enhances adenosine concentrations in the extracellular fluid, affects osteoblast differentiation and whether this effect is mediated by adenosine directly. Dipyridamole at a concentration of 0.5 μM, previously reported to increase extracellular adenosine levels (23), significantly increased osteoblast differentiation of MSCs derived from patients with myeloma (Fig. 2A) and healthy subjects (Fig. 2B) by 1.71 ± 0.45- and 1.55 ± 0.21-fold, respectively, which was blocked completely by cotreatment with the A2BR antagonist, MRS 1754, but not the A2AR antagonist, ZM 241385 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Enhanced osteoblastic differentiation in human MSC cultures by direct A2B stimulation as well as treatment with the nucleoside transport inhibitor dipyridamole via A2BR. Human MSCs derived from patients with MM (A) or healthy control subjects (B) were cultured with osteogenic medium in the presence or absence of 0.5 μM dipyridamole or indicated concentrations of adenosine receptor agonists or antagonists for 14 d for ALP activity assay (bottom panels), or for 21 d for Alizarin Red staining (top panels). ALP activity is expressed as nanomoles p-nitrophenol formed per 104 cells; values are means ± sd of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

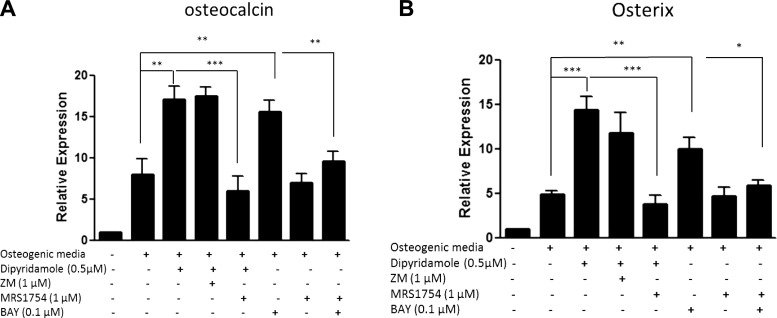

A2BR stimulates osteoblast-associated gene expression

Induction of osteoblast differentiation of normal human MSCs is associated with and due to increased expression of osteoblast genes, including osteocalcin and osterix, at d 14 (Fig. 3). Consistent with the observed osteoblast phenotype (Fig. 2B), dipyridamole and Bay 60–6583 significantly increased the expression of these osteoblast-associated genes (osteocalcin: 2.26±0.55- and 2.14±0.31-fold, respectively; osterix: 2.76±0.51- and 1.97±0.29-fold, respectively), and this up-regulation was reversed by the A2B antagonist MRS 1754 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Increased mRNA expression of osteocalcin and osterix during osteoblast differentiation by direct A2B stimulation, as well as treatment with the nucleoside transport inhibitor dipyridamole via A2BR. Human MSCs derived from healthy bone marrow were cultured with osteogenic medium in the presence or absence of 0.5 μM dipyridamole or indicated concentrations of adenosine receptor agonists or antagonists for 7 d prior to RNA extraction and real-time PCR for osteocalcin (A) and osterix (B). β-Actin served as PCR control. Relative expression was calculated relative to stromal cells without osteogenic medium (fold value 1). Values are shown as means ± sd of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

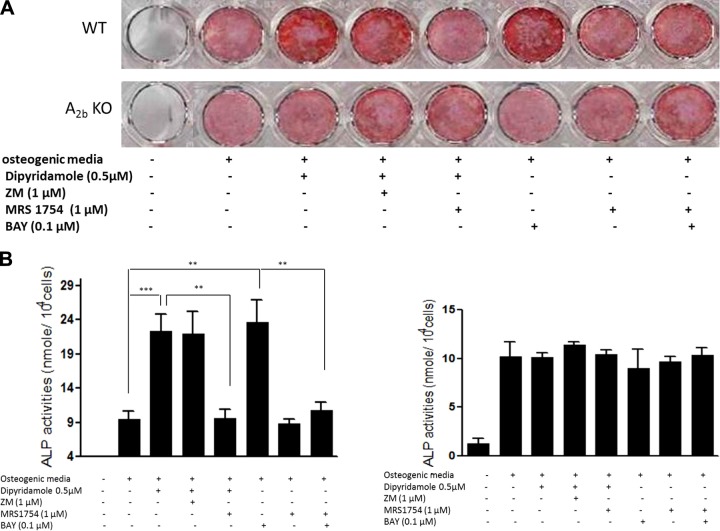

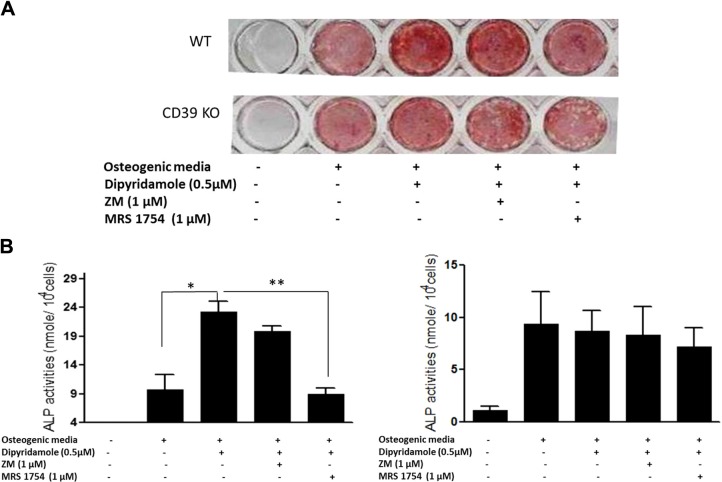

Effect of dipyridamole on osteoblast differentiation is diminished in both A2BR- and CD39-knockout mice

To further confirm that dipyridamole stimulates osteoblast differentiation through stimulation of A2BR, we examined the effect of dipyridamole on osteoblast differentiation of MSCs derived from A2BR-knockout mice and CD39-deficient mice, which convert less ATP/ADP to adenosine in the extracellular space. Dipyridamole and Bay 60–6583 increased the matrix mineralization and ALP activity of osteoblast cultures derived from wild-type mice by 2.44 ± 0.62- and 2.56 ± 0.82-fold, respectively (Fig. 4). However, the effects of dipyridamole and Bay 60–6583 on osteoblast differentiation were completely abrogated in osteoblast cultures derived from A2B-knockout (Fig. 4) and CD39-knockout mice (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Effect of dipyridamole on osteoblast differentiation is diminished in A2BR-knockout mice. Mouse MSCs derived from wild-type mice were cultured with osteogenic medium in the presence or absence of indicated concentrations of 0.5 μM dipyridamole or adenosine receptor agonists or antagonists for 10 d for Alizarin Red staining (A, top panel) or for 4 d for ALP activity assay (B, left panel). MSCs derived from A2B-knockout mice were cultured with osteogenic medium in the presence or absence of 0.5 μM dipyridamole or indicated concentrations of adenosine receptor agonists or antagonists for 21 d for Alizarin Red staining (A, bottom panel) or for 4 d for ALP activity assay (B, right panel). ALP activity is expressed as nanomoles p-nitrophenol formed per 104 cells; values are means ± sd of 4 independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Effect of dipyridamole on osteoblast differentiation is diminished in CD39-knockout mice. Mouse MSCs derived from wild-type mice were cultured with osteogenic medium in the presence or absence of 0.5 μM dipyridamole, 1 μM ZM 241385, or 1 μM MRS 1754 for 10 d for Alizarin Red staining (A, top panel) or for 4 d for ALP activity assay (B, left panel). MSCs derived from CD39-knockout mice were cultured with osteogenic medium in the presence or absence of indicated concentrations of 0.5 μM dipyridamole, 1 μM ZM 241385, or 1 μM MRS 1754 for 10 d for Alizarin Red staining (A, bottom panel) or for 4 d for ALP activity assay (B, right panel). ALP activity is expressed as nanomoles p-nitrophenol formed per 104 cells; values are means ± sd of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we explored the role of all 4 adenosine receptors (A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R) in human bone metabolism; specifically, we have focused on their effects on osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation from human bone marrow. In recent years, studies from our laboratory and others have shown that adenosine is likely to play an important role in modulating bone metabolism (refs. 14–21 and Table 1). However, observations made to date have mostly focused on rodent species, including mice and rats. The role of adenosine receptors in regulating bone marrow cells involved in human bone metabolism has not been well studied. In contrast to the findings reported here, osteoclasts differentiated from peripheral blood cells are unaffected by A1R blockade, and A2AR stimulation enhances osteoclast differentiation after P2X7 receptor stimulation (24). These differences likely reflect differences in osteoclast differentiation from peripheral blood as compared to bone marrow cells.

Table 1.

Effects of adenosine receptors in bone metabolism

| Receptor | Effect | Species |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoclast | ||

| A1 | Blockade inhibits differentiation and function | Mouse (16–18), human (PS) |

| A2A | Stimulation inhibits differentiation and function | Mouse (14, 15), human (14) |

| A2B | Stimulation inhibits differentiation | Mouse (16), human (PS) |

| Osteoblast | ||

| A1 | Stimulates proliferation and differentiation | Human (20) |

| A2A | Stimulates proliferation inhibits differentiation | Human (20), rat (21) |

| A2B | Stimulates differentiation and function | Mouse (19, 22, 45), rat (13), human (20, PS) |

PS, present study.

Dipyridamole is a nonspecific inhibitor of equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs). There are 4 known nucleoside transport proteins in human cells (hENT1–4), and ENT1 and EMT2 are the major cell surface proteins that mediate adenosine uptake of human cells (25). Although both ENT1 and ENT2 are widely distributed (26), they exhibit functional differences and have divergent tissue-specific expression patterns (27–29). A recent study reports that ENT1-deficient mice have elevated plasma adenosine concentrations and ectopic mineralization in spinal tissue (30). To confirm that the actions of dipyridamole on osteoblast differentiation are mediated by adenosine, we examined the effects of dipyridamole on osteoblast differentiation by cells isolated from murine bone marrow incapable of generating extracellular adenosine from ATP and ADP (CD39 deficient) or incapable of responding to adenosine A2BR stimulation. CD39-deficient mice appear normal and have normal ex vivo osteoblast differentiation, although they are reported to be more susceptible to both cardiac and cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injuries, due to increased ATP/ADP level and attenuated adenosine level (31). The results of experiments using CD39- and A2B-knockout mice further confirmed that the effects of dipyridamole are mediated by enhancing the extracellular adenosine concentration. In this regard, it is important to note there was no difference between osteoblasts from patients with myeloma, healthy control subjects, or wild-type mice with respect to their response to dipyridamole. This finding suggests that dipyridamole or other agents capable of increasing extracellular adenosine levels might be useful in treating or preventing bone lesions in patients with MM.

We observed no difference in the extent of osteoblast differentiation of marrow cells derived from A2BR-deficient and wild-type mice. This finding is contrary to an earlier report that A2B-knockout mice have lower bone density (19). This difference may be due to the different source of the knockout mice. Moreover, we used cells from 6- to 8-wk-old female mice, in contrast to the prior studies, which used cells from 15- to 18-wk-old male mice (19). In the mice used by Carroll et al. (19), there was a significant reduction in trabecular bone in 4-wk-old A2B-deficient mice; however, this difference normalized by 8 wk of age. In addition, there was a significant reduction of cortical bone in the 15-wk-old mice, whereas there was no significant difference in the cortical bone at 4 or 8 wk of age. Thus, the capacity of osteoblasts to differentiate differs at different ages at different sites, and these differences may give rise to different in vitro results. Nonetheless, our data confirm those of Carroll et al. (19) with respect to the role of A2BRs in promoting osteoblast differentiation. Previous studies from Eckle et al. (32) show that the cardio protection from ischemic preconditioning by A2BRs is mediated through post-translational regulation of circadian rhythm protein period 2 (Per2), which provides a good candidate for a target of A2BRs in regulation of osteoblast differentiation for future study.

The effect of adenosine and its receptors on destructive bone diseases, such as myeloma, have not previously been explored. Hence, our study provides the first evidence that adenosine stimulates osteoblast differentiation of MSCs from patients with myeloma through activation of A2BRs. Our data also confirm that activation of A2AR and A2BR inhibit osteoclast differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells derived from patients with myeloma. In contrast to such inflammatory bone diseases as wear particle-induced osteolysis, in which A2ARs might be expected to be increased as a result of stimulation by inflammatory cytokines (33, 34) the effect of malignancies on A2AR expression by surrounding cells has not been explored. Our demonstration that A2BR stimulation enhances osteoblast differentiation and inhibits osteoclast differentiation suggests a novel approach to treating myeloma-associated bone disease. Thus, targeting of A2BRs could ameliorate bone destruction in patients with MM.

While our data show that adenosine and its A2BRs promote human stem cell differentiation to osteoblasts even in cells from patients with MM, it remains possible that adenosine modulates other external factors that determine the differentiation bias of human stem cells to differentiation. It is known that there is altered expression of cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, RANK, osteoprotegerin (OPG), and MIP-1α, which leads to unbalanced bone remodeling in myeloma (35–41). Adenosine is reported to regulate the production of IL-6 and OPG in human osteoblast cell lines (42), MIP-1α in RAW cells that can be induced to differentiate to osteoclasts, and TNF-α production by macrophages (43, 44). Many of these cytokines and factors regulate osteoblast differentiation either directly or indirectly. Thus, given the critical roles of these molecules in mediating the interaction between malignant plasma cells with bone cells and their precursors, it is intriguing to ask whether adenosine can regulate the bone marrow microenvironment in myeloma.

In prior studies, we observed that osteoclast precursors from bone marrow taken from patients with MM were significantly more sensitive to the effects of A2AR stimulation (14). A2ARs are up-regulated by a variety of stimuli (33, 34), and, as discussed above, a number of cytokines and growth factors that can affect osteoclasts are released by myeloma cells, any or all of which may have altered A2AR expression (35–42). Moreover, we found that a high concentration of the A2AR agonist CGS21680 (10 μM) was less effective at inhibiting osteoclast differentiation than much lower concentrations (14). No such effect was observed when bone marrow precursors from normal marrows were tested. Although we had originally speculated that this disparity might be due to effects of A2BR stimulation, our current results do not support this hypothesis and may reflect altered signaling at maximal A2AR occupancy, leading to mixed effects on osteoclastogenesis in the cells derived from patients with MM as a result of the prior exposure to abnormal cytokines or other factors, as described above (35–42).

In summary, we have shown here that adenosine and its receptors play an important role in modulating osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation of human bone marrow cells from both healthy individuals and patients with myeloma. Thus, it is possible that adenosine and its receptors may be targeted in the treatment and prevention of MM-associated bone disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (AR56672, AR56672S1 and AR54897), the New York University–Health and Hospitals Corporation (NYU-HHC) Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1RR029893), and the Vilcek Foundation.

Footnotes

- ALP

- alkaline phosphatase

- BMM

- bone marrow macrophage

- BMSC

- bone marrow stromal cell

- CD39

- ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (ENTPD1)

- ENT

- equilibrative nucleoside transporter

- IL

- interleukin

- M-CSF

- macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- MIP

- macrophage inflammatory protein

- MM

- multiple myeloma

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cell

- OPG

- osteoprotegerin

- RANKL

- receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

REFERENCES

- 1. Roodman G. D. (2004) Mechanisms of bone metastasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1655–1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saad F., Lipton A., Cook R., Chen Y. M., Smith M., Coleman R. (2007) Pathologic fractures correlate with reduced survival in patients with malignant bone disease. Cancer 110, 1860–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sonmez M., Akagun T., Topbas M., Cobanoglu U., Sonmez B., Yilmaz M., Ovali E., Omay S. B. (2008) Effect of pathologic fractures on survival in multiple myeloma patients: a case control study. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Melton L. J., 3rd, Kyle R. A., Achenbach S. J., Oberg A. L., Rajkumar S. V. (2005) Fracture risk with multiple myeloma: a population-based study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Valentin-Opran A., Charhon S. A., Meunier P. J., Edouard C. M., Arlot M. E. (1982) Quantitative histology of myeloma-induced bone changes. Br. J. Haematol. 52, 601–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taube T., Beneton M. N., McCloskey E. V., Rogers S., Greaves M., Kanis J. A. (1992) Abnormal bone remodelling in patients with myelomatosis and normal biochemical indices of bone resorption. Eur. J. Haematol. 49, 192–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bataille R., Chappard D., Marcelli C., Dessauw P., Sany J., Baldet P., Alexandre C. (1989) Mechanisms of bone destruction in multiple myeloma: the importance of an unbalanced process in determining the severity of lytic bone disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 7, 1909–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sati H. I., Greaves M., Apperley J. F., Russell R. G., Croucher P. I. (1999) Expression of interleukin-1beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in plasma cells from patients with multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 104, 350–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oyajobi B. O., Franchin G., Williams P. J., Pulkrabek D., Gupta A., Munoz S., Grubbs B., Zhao M., Chen D., Sherry B., Mundy G. R. (2003) Dual effects of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha on osteolysis and tumor burden in the murine 5TGM1 model of myeloma bone disease. Blood 102, 311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitsiades C. S., Mitsiades N. S., Munshi N. C., Richardson P. G., Anderson K. C. (2006) The role of the bone microenvironment in the pathophysiology and therapeutic management of multiple myeloma: interplay of growth factors, their receptors and stromal interactions. Eur. J. Cancer 42, 1564–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hideshima T., Chauhan D., Podar K., Schlossman R. L., Richardson P., Anderson K. C. (2001) Novel therapies targeting the myeloma cell and its bone marrow microenvironment. Semin. Oncol. 28, 607–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tian E., Zhan F., Walker R., Rasmussen E., Ma Y., Barlogie B., Shaughnessy J. D., Jr. 2003. The role of the Wnt-signaling antagonist DKK1 in the development of osteolytic lesions in multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 2483–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qiang Y. W., Chen Y., Stephens O., Brown N., Chen B., Epstein J., Barlogie B., Shaughnessy J. D., Jr. 2008. Myeloma-derived Dickkopf-1 disrupts Wnt-regulated osteoprotegerin and RANKL production by osteoblasts: a potential mechanism underlying osteolytic bone lesions in multiple myeloma. Blood 112, 196–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mediero A., Frenkel S. R., Wilder T., He W., Mazumder A., Cronstein B. N. 2012. Adenosine A2A receptor activation prevents wear particle-induced osteolysis. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 135ra65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mediero A., Kara F. M., Wilder T., Cronstein B. N. (2012) Adenosine A(2A) receptor ligation inhibits osteoclast formation. Am. J. Pathol. 180, 775–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. He W., Cronstein B. N. (2012) Adenosine A1 receptor regulates osteoclast formation by altering TRAF6/TAK1 signaling. Purinergic Signal. 8, 327–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kara F. M., Chitu V., Sloane J., Axelrod M., Fredholm B. B., Stanley E. R., Cronstein B. N. (2010) Adenosine A1 receptors (A1Rs) play a critical role in osteoclast formation and function. FASEB J. 24, 2325–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kara F. M., Doty S. B., Boskey A., Goldring S., Zaidi M., Fredholm B. B., Cronstein B. N. (2010) Adenosine A(1) receptors regulate bone resorption in mice: adenosine A(1) receptor blockade or deletion increases bone density and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss in adenosine A(1) receptor-knockout mice. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 534–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carroll S. H., Wigner N. A., Kulkarni N., Johnston-Cox H., Gerstenfeld L. C., Ravid K. (2012) A2B adenosine receptor promotes mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to osteoblasts and bone formation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15718–15727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Costa M. A., Barbosa A., Neto E., Sa-e-Sousa A., Freitas R., Neves J. M., Magalhaes-Cardoso T., Ferreirinha F., Correia-de-Sa P. (2011) On the role of subtype selective adenosine receptor agonists during proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human primary bone marrow stromal cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 226, 1353–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gharibi B., Abraham A. A., Ham J., Evans B. A. (2011) Adenosine receptor subtype expression and activation influence the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells to osteoblasts and adipocytes. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 2112–2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takedachi M., Oohara H., Smith B. J., Iyama M., Kobashi M., Maeda K., Long C. L., Humphrey M. B., Stoecker B. J., Toyosawa S., Thompson L. F., Murakami S. (2012) CD73-generated adenosine promotes osteoblast differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 227, 2622–2631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Subbarao K., Rucinski B., Rausch M. A., Schmid K., Niewiarowski S. (1977) Binding of dipyridamole to human platelets and to alpha1 acid glycoprotein and its significance for the inhibition of adenosine uptake. J. Clin. Invest. 60, 936–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pellegatti P., Falzoni S., Donvito G., Lemaire I., Di Virgilio F. (2011) P2X7 receptor drives osteoclast fusion by increasing the extracellular adenosine concentration. FASEB J. 25, 1264–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Young J. D., Yao S. Y., Sun L., Cass C. E., Baldwin S. A. (2008) Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) family of nucleoside and nucleobase transporter proteins. Xenobiotica 38, 995–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. King A. E., Ackley M. A., Cass C. E., Young J. D., Baldwin S. A. (2006) Nucleoside transporters: from scavengers to novel therapeutic targets. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 416–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grenz A., Bauerle J. D., Dalton J. H., Ridyard D., Badulak A., Tak E., McNamee E. N., Clambey E., Moldovan R., Reyes G., Klawitter J., Ambler K., Magee K., Christians U., Brodsky K. S., Ravid K., Choi D. S., Wen J., Lukashev D., Blackburn M. R., Osswald H., Coe I. R., Nurnberg B., Haase V. H., Xia Y., Sitkovsky M., Eltzschig H. K. (2012) Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1) regulates postischemic blood flow during acute kidney injury in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 693–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28. Morote-Garcia J. C., Rosenberger P., Nivillac N. M., Coe I. R., Eltzschig H. K. (2009) Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent repression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter 2 attenuates mucosal inflammation during intestinal hypoxia. Gastroenterology 136, 607–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eckle T., Hughes K., Ehrentraut H., Brodsky K. S., Rosenberger P., Choi D. S., Ravid K., Weng T., Xia Y., Blackburn M. R., Eltzschig H. K. 2013. Crosstalk between the equilibrative nucleoside transporter ENT2 and alveolar Adora2b adenosine receptors dampens acute lung injury. [E-pub ahead of print] FASEB J. 10.1096/fj.13-228551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Warraich S., Bone D. B., Quinonez D., Ii H., Choi D. S., Holdsworth D. W., Drangova M., Dixon S. J., Seguin C. A., Hammond J. R. (2013) Loss of equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 in mice leads to progressive ectopic mineralization of spinal tissues resembling diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in humans. J. Bone Miner. Res. 28, 1135–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eltzschig H. K., Sitkovsky M. V., Robson S. C. (2012) Purinergic signaling during inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2322–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eckle T., Hartmann K., Bonney S., Reithel S., Mittelbronn M., Walker L. A., Lowes B. D., Han J., Borchers C. H., Buttrick P. M., Kominsky D. J., Colgan S. P., Eltzschig H. K. (2012) Adora2b-elicited Per2 stabilization promotes a HIF-dependent metabolic switch crucial for myocardial adaptation to ischemia. Nat. Med. 18, 774–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khoa N. D., Montesinos M. C., Reiss A. B., Delano D., Awadallah N., Cronstein B. N. (2001) Inflammatory cytokines regulate function and expression of adenosine A2A receptors in human monocytic THP-1 cells. J. Immunol. 167, 4026–4032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nguyen D. K., Montesinos M. C., Williams A. J., Kelly M., Cronstein B. N. (2003) Th1 cytokines regulate adenosine receptors and their downstream signaling elements in human microvascular endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 171, 3991–3998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barille S., Collette M., Bataille R., Amiot M. (1995) Myeloma cells upregulate interleukin-6 secretion in osteoblastic cells through cell-to-cell contact but downregulate osteocalcin. Blood 86, 3151–3159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lust J. A., Donovan K. A. (1999) The role of interleukin-1 beta in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 13, 1117–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lai F. P., Cole-Sinclair M., Cheng W. J., Quinn J. M., Gillespie M. T., Sentry J. W., Schneider H. G. (2004) Myeloma cells can directly contribute to the pool of RANKL in bone bypassing the classic stromal and osteoblast pathway of osteoclast stimulation. Br. J. Haematol. 126, 192–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goranova-Marinova V., Goranov S., Pavlov P., Tzvetkova T. (2007) Serum levels of OPG, RANKL and RANKL/OPG ratio in newly-diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma: clinical correlations. Haematologica 92, 1000–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hashimoto T., Abe M., Oshima T., Shibata H., Ozaki S., Inoue D., Matsumoto T. (2004) Ability of myeloma cells to secrete macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1alpha and MIP-1beta correlates with lytic bone lesions in patients with multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 125, 38–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Uneda S., Hata H., Matsuno F., Harada N., Mitsuya Y., Kawano F., Mitsuya H. (2003) Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha is produced by human multiple myeloma (MM) cells and its expression correlates with bone lesions in patients with MM. Br. J. Haematol. 120, 53–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Filella X., Blade J., Guillermo A. L., Molina R., Rozman C., Ballesta A. M. (1996) Cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-1alpha) and soluble interleukin-2 receptor as serum tumor markers in multiple myeloma. Cancer Detect. Prev. 20, 52–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Evans B. A., Elford C., Pexa A., Francis K., Hughes A. C., Deussen A., Ham J. (2006) Human osteoblast precursors produce extracellular adenosine, which modulates their secretion of IL-6 and osteoprotegerin. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 228–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Szabo C., Scott G. S., Virag L., Egnaczyk G., Salzman A. L., Shanley T. P., Hasko G. (1998) Suppression of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1alpha production and collagen-induced arthritis by adenosine receptor agonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 125, 379–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hasko G., Kuhel D. G., Chen J. F., Schwarzschild M. A., Deitch E. A., Mabley J. G., Marton A., Szabo C. (2000) Adenosine inhibits IL-12 and TNF-α production via adenosine A2a receptor-dependent and independent mechanisms. FASEB J. 14, 2065–2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gharibi B., Abraham A. A., Ham J., Evans B. A. (2012) Contrasting effects of A1 and A2b adenosine receptors on adipogenesis. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 36, 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]