Abstract

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting multiple organ systems, such as the skin, joints, blood vessels, central nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract. Intestinal BD is characterized by intestinal ulcerations and gastrointestinal symptoms. The medical treatment of intestinal BD includes corticosteroids and immunosupressants. There have been several reports of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) blockers being successful in treatment of refractory intestinal BD. Here, we report on a patient who was diagnosed with intestinal BD despite treatment with the fully humanized TNF-α blocker (adalimumab) for underlying ankylosing spondylitis. This patient achieved clinical remission and complete mucosal healing through the addition of a steroid and azathioprine to the adalimumab regimen.

Keywords: Intestinal Behçet’s disease, Tumor necrosis factor-α, Adalimumab

Core tip: Here, we report on a patient who was diagnosed with intestinal Behçet’s disease despite treatment with the fully humanized tumor necrosis factor-α blocker (adalimumab) for underlying ankylosing spondylitis. This patient achieved clinical remission and complete mucosal healing through the addition of a steroid and azathioprine to the adalimumab regimen.

INTRODUCTION

Behçet’s disease (BD) involves multiple organ systems, such as the skin, joints, blood vessels, central nervous system, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract[1]. Intestinal BD is characterized by intestinal ulcerations and gastrointestinal symptoms[2]. The incidence of BD involving the GI tract varies by country, ranging from 3% to 60% of cases of BD[3]. GI bleeding and perforation can be associated with intestinal BD, with resultant comorbidities[1]. The medical treatment for intestinal BD includes corticosteroids and immunosupressants. Unfortunately, surgical treatment, such as ileocecal resection, is sometimes necessary for intestinal BD with perforation, intractable pain, and hemorrhage which are refractory to conventional therapy[4]. There have been several reports of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) blockers being successful in refractory intestinal BD. Most of these reported on the efficacy of infliximab[4-9] and a few reported on the efficacy of adalimumab[10,11]. Here, we report on a patient who was diagnosed with intestinal BD despite being treated with the fully humanized TNF-α blocker (adalimumab) for underlying ankylosing spondylitis. This patient achieved and maintained clinical remission and complete mucosal healing through the addition of a steroid and azathioprine to the adalimumab regimen for 43 mo.

CASE REPORT

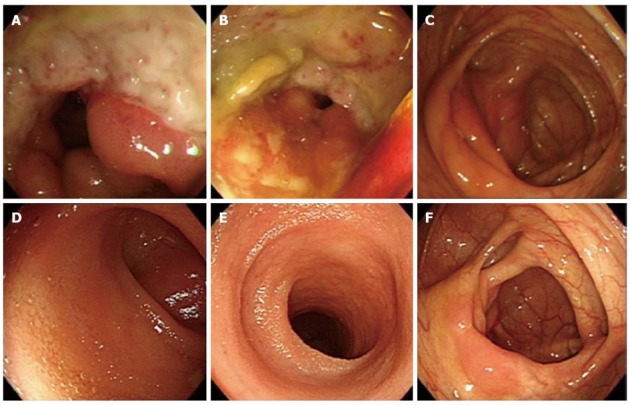

A 29-year-old male patient was hospitalized due to severe right lower quadrant abdominal pain for the preceding 15 d. He had experienced recurrent oral ulcerations and arthralgia for 15 years and had had an erythematous papule on his back for the past 2 years. He had undergone appendectomy for appendicitis 17 years ago. He was diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis 2 years ago because of lower back and shoulder pain. He had taken salazopyrine 1000 mg for 2 mo and had been injected with infliximab for his ankylosing spondylitis for 9 mo (5 mg/kg intravenously at 0, 2 and 6 wk; 5 mg/kg intravenously every 8 wk). The oral ulcerations, arthralgias, and erythematous papule on his back had improved, but his back pain had not been improved at that time. Therefore, the infliximab had been switched to adalimumab (40 mg subcutaneously every 2 wk) since 10 mo ago. On physical examination at admission, he appeared acutely ill, and had a blood pressure of 120/70 mmHg, a pulse of 84 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min, and a temperature of 36.5 °C. The abdomen was flat with direct tenderness in the right lower quadrant. Bowel sounds were normal. The results of laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count (WBC) of 20930/mm3; hemoglobin, 13.9 g/dL; hematocrit, 41.7%; platelet count, 282000/mm3; total protein, 7.2 g/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate increased to 33 mm/h; and C-reactive protein increased to 111 mg/L. A colonoscopy performed on admission showed a well-demarcated, large, deep ulcer with an exudate, mucosal edema, and erythema at the terminal ileum (Figure 1A-C). Colonic biopsies at the terminal ileum showed an ulcer with a necroinflammatory exudate. On computed tomography, bowel wall thickening and prominent enhancement with surrounding fat infiltration were noted at the terminal ileum and cecum, suggesting active inflammation (Figure 2). Finally he was diagnosed as intestinal BD according to the clinical symptoms and examination. The disease activity index for intestinal Behçet’s disease (DAIBD) was 90, reflecting severe disease activity[12]. Subsequently, the patient was treated with conventional medical therapy, including azathioprine 150 mg and 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA, Pentasa) 3000 mg/d. His abdominal pain seemed to decrease after 10 d. However, the patient’s severe right lower quadrant abdominal pain recurred after one month. The DAIBD score at the time of recurrent abdominal pain was 80, again reflecting severe disease activity[12]. In the early stages of treatment, clinical remission could not be obtained through combination therapy with azathioprine and 5-ASA. Thus, at the time of abdominal pain recurrence, intravenous hydrocortisone (300 mg/d) was administrated. Then the abdominal pain was improved 2 d after steroid injection. Intravenous hydrocortisone was slowly tapered to oral prednisolone for 2 mo. Finally, DAIBD score was 10. A follow-up colonoscopy after 36 mo demonstrated that the ulcer at the terminal ileum was replaced by normal mucosa (Figure 1D-F) with complete mucosal healing. Combination therapy with azathioprine, 5-ASA and adalimumab was continued for 43 mo with clinical and endoscopic remission.

Figure 1.

A colonoscopy on admission revealed a large, deep, well-demarcated ulcer with exudate, mucosal edema and erythema at the terminal ileum (A-C). On follow-up colonoscopy at 36 mo, the ulcer at the terminal ileum was replaced by normal mucosa (D-F) with complete mucosal healing.

Figure 2.

In computed tomography, arrow showed bowel wall thickening and prominent enhancement with surrounding fat infiltration at the terminal ileum and cecum. This was suggestive of active inflammation.

DISCUSSION

We reported on a 29-year-old man with BD and ankylosing spondylitis who developed intestinal BD despite continuous use of adalimumab. We treated this patient with intravenous steroids to induce clinical remission and with azathioprine and 5-ASA for maintenance of remission. This case is unique in two ways. First, the terminal ileal ulcer characteristic of intestinal BD appeared while the patient was receiving adalimumab for ankylosing spondylitis. Second, mucosal healing was achieved and maintained through combination therapy with azathioprine and 5-ASA after induction of remission with intravenous steroids.

Conventional therapies such as mesalamine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, thalidomide, bowel rest, and total parenteral nutrition have been used in the treatment of intestinal BD[13]. However, in patients with intestinal BD unresponsive to conventional therapies, TNF-α blockers have been shown to improve symptoms[12]. Both infliximab and adalimumab can be used for treatment of intestinal BD because they are similar active biologics, monoclonal antibodies to TNF-α[10,11,14]. There has been no data available regarding the comparative efficacy of infliximab and adalimumab in intestinal BD. In Table 1 there have been many publications reporting on the effectiveness of infliximab[4-9]. However, there have been only a few reports of the efficacy of adalimumab in treating intestinal BD[10,11]. Infliximab with combination therapies, such as 5-ASA and immunosuppressants, in patients with intestinal BD is effective for the induction and maintenance of remission[4-9,11,14]. In the case of adalimumab, adalimumab was reported to be effective in inducing complete remission as monotherapy[10]. We suggest three reasons why this patient may have developed an ulcer of the terminal ileum during the use of adalimumab, but not during the use of infliximab. First, the two medicines have different routes of injection, with adalimumab injected subcutaneously (SQ) and infliximab injected intravenously. When infliximab is injected intravenously, it enters the venous circulation directly with 100% bioavailability and no absorption phase, thereby reaching a more rapid therapeutic range than achieved with subcutaneous injection. Conversely, the bioavailability of an adalimumab 40 mg SQ dose has been estimated as 64%[15]. Second, there might be a difference in the effective dose between adalimumab and infliximab. Adalilmumab is used to be injected as fixed dose irrespective of body weight (40 mg subcutaneously every 2 wk) but infliximab is used to be injected according to the body weight (5 mg/kg at 0, 2 and 6 wk; 5 mg/kg every 8 wk). Compared to the infliximab, adalilmumab in fixed dose was supposed to be less effective in this patient with 22.8 kg/m2 body mass index because of shortage of dose. Third, intravenous injection might be more potent than subcutaneous injection because BD is characterized by systemic vasculitis[16]. Infliximab and adalimumab are different medicines having unique pharmacokinetics. There was no head to head study for comparing effectiveness of infliximab and adalimumab. Further studies are warranted to compare the efficacy of adalimumab and infliximab in patients with intestinal BD.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease receiving infliximab or adalimumab

| Case | Age (yr)/gender | Duration of disease (yr) | Anti TNF-α Ab for induction | Previous therapies | Maintenance therapy | Outcomes | Follow-up duration after achieving remission | Ref. |

| 1 | 32/F | 5 | IFX | Steroids | IFX | Remission | 9 mo | [14] |

| 6-MP | 6-MP | |||||||

| 2 | 37/F | 2 | IFX | Mesalamine | IFX | Remission | 16 mo | [14] |

| Steroids | 6-MP | |||||||

| 6-MP | ||||||||

| 3 | 51/M | 4 | IFX | Steroids | IFX | Remission | 3 yr | [14] |

| Methotrexate | ||||||||

| 4 | 38/M | 5 | IFX | Steroids | IFX | Remission | 10 mo | [14] |

| Colchicines | ||||||||

| Cyclosporine A | ||||||||

| 5 | 43/F | 6 | IFX | Steroids | AZA | Surgery | 6 mo | [14] |

| Azathioprine | ||||||||

| 6 | 38/M | 3 | IFX | Steroids | IFX | Remission | 2 yr | [14] |

| 6-MP | 6-MP | |||||||

| 7 | 35/F | Over 20 | IFX | Steroids | Methotrexate | Relapse | 8 mo1 | [7] |

| Azathioprine | ||||||||

| 8 | 27 /F | 2 | IFX | Steroids | Steroids | Remission | 17 mo | [5] |

| Thalidomide | Thalidomide | |||||||

| 9 | 30 /F | 3 | IFX | Steroids | Thalidomide | Relapse | 10 mo1 | [5] |

| Colchicines | ||||||||

| Cyclosporine | ||||||||

| 10 | 42/M | 11 | IFX | Steroids | - | Remission | 1 wk | [9] |

| Colchicine | ||||||||

| 11 | 47/M | 20 | IFX | Sulfasalazine | - | Remission | 12 mo | [4] |

| Steroids | ||||||||

| Azathioprine | ||||||||

| 12 | 30/F | - | IFX | Steroids | IFX | Remission | 22 mo | [10] |

| Azathioprine | Switch to adalimumab | |||||||

| 13 | 45/F | 9 | IFX | Mesalamine | IFX | Remission | 25 wk | [6] |

| Steroids | ||||||||

| 6-MP |

Duration between remission stage and the first relapse stage after infusion of anti tumor necrosis factor-α antibody (anti TNF-α Ab). F: Female; M: Male; IFX: Infliximab; 6-MP: 6-mercaptopurine.

In conclusion, this is the first case report of intestinal BD appearing despite the use of adalimumab. Furthermore, the subject in this case improved with the conventional combination of intravenous steroids for the induction of remission and azathioprine and 5-ASA for maintenance of remission. Despite the use of adalimumab, a conventional combination of therapies including intravenous steroids, azathioprine, and 5-ASA might be important in treating patients with intestinal BD.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Cuzzocrea S, Lukashevich IS S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Iwata S, Saito K, Yamaoka K, Tsujimura S, Nawata M, Hanami K, Tanaka Y. Efficacy of combination therapy of anti-TNF-α antibody infliximab and methotrexate in refractory entero-Behçet’s disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21:184–191. doi: 10.1007/s10165-010-0370-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi K, Ueno F, Bito S, Iwao Y, Fukushima T, Hiwatashi N, Igarashi M, Iizuka BE, Matsuda T, Matsui T, et al. Development of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease using a modified Delphi approach. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:737–745. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayraktar Y, Ozaslan E, Van Thiel DH. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behcet’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:144–154. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JH, Kim TN, Choi ST, Jang BI, Shin KC, Lee SB, Shim YR. Remission of intestinal Behçet’s disease treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody (Infliximab) Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22:24–27. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2007.22.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis SP, Czajkowski M, McGovern DP, Watson RG, Bell AL. Treatment of intestinal Behçet’s syndrome with chimeric tumour necrosis factor alpha antibody. Gut. 2001;49:725–728. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.5.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassard PV, Binder SW, Nelson V, Vasiliauskas EA. Anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody therapy for gastrointestinal Behçet’s disease: a case report. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:995–999. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kram MT, May LD, Goodman S, Molinas S. Behçet’s ileocolitis: successful treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody (infliximab) therapy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:118–121. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6506-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byeon JS, Choi EK, Heo NY, Hong SC, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH, Song JK, Yoo B, Yu CS. Antitumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy for early postoperative recurrence of gastrointestinal Behçet’s disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:672–676. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0813-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ju JH, Kwok SK, Seo SH, Yoon CH, Kim HY, Park SH. Successful treatment of life-threatening intestinal ulcer in Behçet’s disease with infliximab: rapid healing of Behçet’s ulcer with infliximab. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1383–1385. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ariyachaipanich A, Berkelhammer C, Nicola H. Intestinal Behçet’s disease: maintenance of remission with adalimumab monotherapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1769–1771. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Laar JA, Missotten T, van Daele PL, Jamnitski A, Baarsma GS, van Hagen PM. Adalimumab: a new modality for Behçet’s disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:565–566. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.064279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sfikakis PP. Behçet’s disease: a new target for anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61 Suppl 2:ii51–ii53. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_2.ii51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284–1291. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naganuma M, Sakuraba A, Hisamatsu T, Ochiai H, Hasegawa H, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Hibi T. Efficacy of infliximab for induction and maintenance of remission in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1259–1264. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neri P, Zucchi M, Allegri P, Lettieri M, Mariotti C, Giovannini A. Adalimumab (Humira™): a promising monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha in ophthalmology. Int Ophthalmol. 2011;31:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10792-011-9430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altintaş E, Senli MS, Polat A, Sezgin O. A case of Behçet's disease presenting with massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2009;20:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]