Abstract

Background

Recent studies have extended our understanding of the pathophysiology, natural course, and treatment of vestibular vertigo. The relative frequency of the different forms is as follows: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) 17.1%; phobic vestibular vertigo 15%; central vestibular syndromes 12.3%; vestibular migraine 11.4%; Menière’s disease 10.1%; vestibular neuritis 8.3%; bilateral vestibulopathy 7.1%; vestibular paroxysmia 3.7%.

Methods

Selective literature survey with particular regard to Cochrane reviews and the guidelines of the German Neurological Society.

Results

In more than 95% of cases BPPV can be successfully treated by means of liberatory maneuvers (controlled studies); the long-term recurrence rate is 50%. Corticosteroids improve recovery from acute vestibular neuritis (one controlled, several noncontrolled studies); the risk of recurrence is 2–12%. A newly identified subtype of bilateral vestibulopathy, termed cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, and vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS), shows no essential improvement in the long term. Long-term high-dose treatment with betahistine is probably effective against Menière’s disease (noncontrolled studies); the frequency of episodes decreases spontaneously in the course of time (> 5 years). The treatment of choice for vestibular paroxysmia is carbamazepine (noncontrolled study). Aminopyridine, chlorzoxazone, and acetyl-DL-leucine are new treatment options for various cerebellar diseases.

Conclusion

Most vestibular syndromes can be treated successfully. The efficacy of treatments for Menière’s disease, vestibular paroxysmia, and vestibular migraine requires further research.

Vertigo is not a single disease entity but the cardinal symptom of different diseases of varying etiology; these may arise from the inner ear, brainstem, or cerebellum or may be of psychic origin (1, 2). Internistic causes are unlikely in pure rotatory vertigo and are usually overrated; postural vertigo may result from orthostatic dysregulation or from adverse effects of medications such as antihypertensive or anticonvulsive drugs.

Around 30% of people will suffer from rotatory or postural vertigo at some point in their lives (3), and vertigo is also a very frequent symptom in emergency patients. This review is therefore aimed at physicians from a range of specialties from primary care to internal medicine, neurology, otorhinolaryngology, and psychiatry.

Definition.

Vertigo is not a single disease entity but the cardinal symptom of different diseases of varying etiology; these may arise from the inner ear, brainstem, or cerebellum or may be of psychic origin.

Despite the great clinical importance of vertigo, patients exhibiting this cardinal symptom often receive insufficient or inappropriate care. This is true for both diagnosis (long delay from presentation to correct diagnosis with too many, mostly unnecessary technical examinations) and treatment (administration of too many, mostly ineffective, often purely symptomatic medications). An ongoing study of our own and a study from Switzerland (4) corroborate this assessment. To improve this situation and with the intention of establishing an international, interdisciplinary research center, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) set up an integrated research and treatment center (IFB) for vertigo, balance and oculomotor disorders (German Center for Vertigo and Balance Disorders) in Munich in 2009 (5). The forms of vertigo most frequently diagnosed at this center are shown in Table 1: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is most common, accounting for almost 17.1% of all cases, followed by phobic vestibular vertigo (15%) and the group of central vestibular syndromes, found predominantly in patients with vascular, inflammatory (MS), and degenerative diseases of the brainstem or cerebellum (12.3%). Vestibular migraine (11.4%) is the most common cause of spontaneously occurring, episodic vertigo. The next two most frequent diagnoses are Menière’s disease (10.1%) and vestibular neuritis (8.3%). Together, these six diseases account for around 70% of all cases of vertigo. Our experience indicates that these figures essentially reflect the distribution of the forms of vertigo in the general population.

Table 1. Frequency of various forms of vertigo among 17 718 patients at a specialized interdisciplinary center*1.

| Form of vertigo | Frequency n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | 3036 | 17.1 |

| Somatoform phobic vestibular vertigo | 2661 | 15.0 |

| Central vestibular syndromes | 2178 | 12.3 |

| Vestibular migraine | 2017 | 11.4 |

| Menière’s disease | 1795 | 10.1 |

| Vestibular neuritis | 1462 | 8.3 |

| Bilateral vestibulopathy | 1263 | 7.1 |

| Vestibular paroxysmia | 655 | 3.7 |

| Psychogenic vertigo (other) | 515 | 2.9 |

| Perilymphatic fistula | 93 | 0.5 |

| Vertigo of unknown origin | 480 | 2.7 |

| Other*2 | 1563 | 8.8 |

| Total | 17718 | 100.00 |

*1 988–2012: Vertigo clinic of Ludwig Maximilian University and the German Center for Vertigo and Balance Disorders

*2Includes, among others, nonvestibular vertigo in neurodegenerative diseases, nonvestibular oculomotor disorders in myasthenia gravis, and peripheral ocular muscle paresis

The present review concentrates not only on the treatment of vestibular forms of vertigo—a central task for physicians—but also on the natural course and, particularly important in chronically recurring episodic forms, the frequency of attacks or recurrences in the long term.

Learning goals

After reading this article the reader should be familiar with:

The natural course and recurrence rate of the most frequent vestibular syndromes

The physical and medical treatment of the various forms of BPPV

The pharmacotherapy of vestibular neuritis, Menière’s disease, vestibular paroxysmia and cerebellar vertigo syndromes, nystagmus, and gait disorders.

This article is based on a new selective survey of the literature, with particular regard to Cochrane reviews and the guidelines of the German Neurological Society (6), and on the recently published second edition of a book on vertigo (1).

Recent studies have provided new findings on the natural course and specific treatment of the following forms of vertigo:

BPPV, arising in the posterior, horizontal, or anterior semicircular canal

Menière’s disease, including the visualization of endolymphatic hydrops by high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Acute vestibular neuritis

Bilateral vestibulopathy

Vestibular paroxysmia

Central vestibular syndromes (7).

Common forms of vertigo.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

Phobic vestibular vertigo

Central vestibular syndromes

Menière’s disease

Vestibular neuritis

Four examples of new findings on medicinal treatment relevant to clinical practice are the following: (a) Corticosteroids probably improve the recovery of peripheral labyrinthine function in acute vestibular neuritis; however, this needs confirmation. (b) The most effective medication for Menière’s disease is evidently prophylactic long-term high-dose betahistine; this drug brings about dose-dependent improvement of blood flow in the inner ear. (c) Carbamazepine reduces attacks of vestibular paroxysmia even in the long term (Table 2). (d) Administration of aminopyridine has become an important pharmacological treatment principle for:

Table 2. Drug treatment of vestibular vertigo and oculomotor disorders, arranged by substance group*1.

| Substance group | Indication | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Antiepileptics |

|

Carbamazepine (400–800 mg/day) Oxcarbazepine (300–600 mg/day) Carbamazepine (800–2000 mg/day) or other anticonvulsives |

| Vestibular migraine | For prophylaxis:

|

|

| Antivertigo drugs |

|

|

| Beta-receptor blockers | Vestibular migraine | For prophylaxis, e.g., metoprolol succinate (ca. 50–200 mg/day) |

| Betahistine | Menière’s disease | Betahistine dihydrochloride (3×48 mg/day) |

| Ototoxic antibiotics |

|

|

| Corticosteroids | Acute vestibular neuritis |

|

| Acute Cogan syndrome and other autoimmune inner ear diseases |

|

|

Potassium channel blockers:

|

|

|

| Potassium channel blockers: 4-Aminopyridine | Episodic ataxia type 2 |

|

| Carboanhydrase inhibitors: acetazolamide |

|

|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) | Phobic vestibular vertigo |

|

BPPV, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

*1Modified from (1)

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

In most cases BPPV arises from canalolithiasis, caused by otoconia (calcite crystals) that have been dislodged from the utricle and are moving freely in the semicircular canals. The cardinal symptom are attacks of vertigo—lasting several seconds and sometimes severe—triggered by changes in position of the head or body relative to gravity (turning or sitting up in bed, lying or bending down). BPPV can occur at any time of life from childhood to old age; the annual incidence increases with increasing age. In 95% of cases the etiology remains unknown.

The most frequent causes are:

Head injury

Status post vestibular neuritis; around 15% of all patients with acute vestibular neuritis develop “postinfectious BPPV” within weeks or months of the acute episode, because the inflammation often extends to the labyrinth.

A long period of confinement to bed.

Furthermore, BPPV may be associated with Menière’s disease and vestibular migraine. Finally, osteopenia, osteoporosis, and/or low serum concentrations of vitamin D have relatively often been described in “idiopathic BPPV” (12). Anatomically, three forms of BPPV are distinguished.

Age at onset.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo can occur at any time of life from childhood to old age; the annual incidence increases with increasing age.

BPPV of the posterior canal (pc-BPPV)

Around 90% of cases of BPPV arise in the posterior semicircular canal. The diagnosis of this subtype is confirmed by exhaustible positional nystagmus, rotating to the ear positioned under the head and beating to the forehead, following positioning of the head in the plane of the affected posterior canal. The success rates of repeated performance of the Sémont liberatory maneuver or the Epley repositioning maneuver are over 95% in pc-BPPV (1). Patients with severe nausea should be given antivertigo drugs, e.g., dimenhydrinate 30 minutes before the maneuver (Table 2). After careful instruction entailing practical demonstration and provision of illustrations, most patients can successfully perform the liberatory maneuver unaided at home (frequency and duration: three times in the morning, three times in the afternoon, and three times in the evening, usually for three days). The most important thing is to ensure correct positioning of the head.

Clinical experience shows that patients are usually free of symptoms after some days. Subsequently, probably owing to repositioning of the otoconia onto the utricular macula, postural vertigo lasting several days can be expected; patients should be warned about this complication.

Three forms of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) can be distinguished.

Posterior BPPV (90%)

Horizontal BPPV (5–10%)

Anterior BPPV (< 5%)

BPPV of the horizontal canal (hc-BPPV)

This less common subtype of BPPV (ca. 5–10%) is characterized by linear horizontal nystagmus on positional maneuvers. In canalolithiasis the nystagmus beats to the ear under the head (higher intensity on the affected side), while in cupulolithiasis (when the otoconia adhere to the cupula) it beats to the upward ear (higher intensity on the nonaffected side). Various treatment procedures have been described for canalolithiasis of the horizontal canal, and those employed most frequently are gradual 90° rotations around the longitudinal axis of the body towards the nonaffected ear, lying on the nonaffected ear for 12 h, a combination of both (1), and the Gufoni maneuver (13). The Gufoni maneuver can be used successfully to treat both canalolithiasis (e1) and cupulolithiasis (e2). The patient is moved from a sitting position to lying on the side where the nystagmus is less pronounced. The head is then turned 45° downward, after which the patient sits up again. The advantage of this maneuver is that there is no need to determine which form of hc-BPPV is involved. In cases of cupulolithiasis of the horizontal canal, an alternative to the Gufoni maneuver is to first convert the cupulolithiasis to canalolithiasis. This can be achieved by means of the Brandt–Daroff maneuver or, even more effectively, by shaking the head after bending it 90° forwards into the vertical plane. One of the above-mentioned liberatory maneuvers for canalolithiasis of the horizontal canal can then be used; all are effective.

BPPV of the anterior canal (ac-BPPV)

Anterior canal BPPV remains controversial, and some even doubt its existence. Figures for the relative frequency of ac-BPPV therefore vary between 0 and 5%. Vertigo and nystagmus are provoked by the same diagnostic positioning test as in pc-BPPV. The nystagmus beats vertically downward, with a torsional component that beats with the upper pole of the eye to the affected ear. In a noncontrolled study the Yacovino maneuver (gradual lifting of the overextended head in head-down position, followed by sitting up) was reported to achieve remission in 85% of cases when performed once and 100% after several repetitions (14).

Gufoni maneuver.

The Gufoni maneuver can be used successfully to treat both canalolithiasis and cupulolithiasis in horizontal BPPV.

Drug treatment.

Antiepileptics, antivertigo drugs, beta-receptor blockers, betahistine, ototoxic antibiotics, corticosteroids, calcium-channel blockers, carboanhydrase inhibitors, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors can be used.

ac-BPPV.

Vertigo and nystagmus are provoked by the same diagnostic positioning test as in pc-BPPV. The nystagmus beats vertically downward with a torsional component.

Natural course of BPPV

Untreated, BPPV persists in around 30% of patients. The rate of spontaneous recovery is strikingly high, over 60% within 4 weeks. Monitoring of 125 patients with pc-BPPV for a mean of 10 years revealed a recurrence rate of 50% after initial cure (15). Most of these recurrences (80%) came within a year of treatment, independent of the type of liberatory maneuver; women suffered recurrences more frequently than men (58% vs 39%), and the rate of recurrence was much lower in the seventh than in the sixth decade of life (15). The recurrences were again treated by means of a liberatory maneuver appropriate to the semicircular canal affected. Controlled limitation of changes in head and body position does not influence the frequency of recurrence.

Vestibular neuritis

Vestibular neuritis (also known as vestibular neuropathy) probably arises from reactivation of a latent infection of the vestibular ganglion with herpes simplex virus type I, leading to an incomplete, unilateral, purely vestibular loss of labyrinthine function. The principal symptoms are severe rotatory vertigo with apparent movement of objects in the visual field (oscillopsia) and nausea, horizontally rotating spontaneous nystagmus to the nonaffected side, gait deviation to the affected side and a tendency to fall to the affected side; these symptoms are acute in onset and persist for many days. The head impulse test shows impaired function of the vestibulo-ocular reflex when the patient turns in the direction of the affected ear. The caloric reflex test confirms reduction or absence of excitability of the horizontal semicircular canal. Acute audiological and other neurological symptoms, especially central oculomotor or vestibular signs (above all vertical divergence [skew deviation], gaze saccades, gaze nystagmus, or central fixation nystagmus) are absent (16), which is important in differentiating vestibular neuritis from central “pseudo-vestibular neuritis” caused by lacunar cerebral infarction or multiple sclerosis plaques.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

High spontaneous recovery rate (>70%)

High recurrence rate (ca. 50%)

Treatment

If the patient is suffering severe nausea and retching, antivertigo medication can be administered in the first few days to relieve the symptoms (Table 2); however, prolonged administration delays central compensation of the peripheral vestibular deficit. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 141 patients showed that recovery of peripheral vestibular function was significantly improved by monotherapy with methylprednisolone (17). These findings were confirmed in another study (e3). This trend one month after illness was also discerned in a Cochrane review, but no general recommendation for corticosteroid treatment was given because of the insufficient number of studies (18). The efficacy of physiotherapy with dynamic exercises for balance regulation and of gaze stabilization for improvement of central vestibulospinal compensation has been confirmed by a prospective randomized controlled trial (19) and a Cochrane review (20). To date, there are no corresponding clinical studies on improvement of central compensation by drugs; a BMBF-sponsored study of the effect of betahistine on central compensation (BETAVEST) is being carried out.

Natural course and complications

Over the course of time the rate of recovery of peripheral vestibular function ranges from 40% to 63% depending on early treatment with corticosteroids (21). Long-term monitoring of 103 patients for a mean of almost 10 years revealed a recurrence in only two patients (1.9%), in each case in the contralateral ear and with far less severe symptoms owing to the existing damage to the other nerve (22). Another observational study reported recurrences in 11.7% of the patients (e4). Around 15% of patients with vestibular neuritis develop “postinfectious BPPV” in the affected ear within a few weeks or months because not only the nerve is infected but also the labyrinth (e5).

Bilateral vestibulopathy (BVP)

The cardinal symptoms of BVP are motion-dependent postural vertigo with unsteady gait and stance, particularly in darkness and on uneven ground (vestibulospinal functional impairment), together with oscillopsia and blurred vision when walking or moving the head (functional impairment of vestibulo-ocular reflex). Patients with BVP are typically symptom free when sitting or lying. BVP involves circumscribed atrophy of the hippocampus with impairments of spatial memory and navigation (23), and is the most frequent cause of motion-dependent postural vertigo in older patients. There are many possible causes of BVP; the three most frequently identified are:

Ototoxic aminoglycosides

Bilateral Menière’s disease

Meningitis (24).

Effect of glucocorticoid treatment.

The effect of glucocorticoids in the treatment of acute vestibular neuritis has to be studied further.

One connection between BVP and degenerative cerebellar diseases has now been clearly established (24– 26): In our experience, cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, and vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS), comprising BVP in combination with sensory axonal polyneuropathy, cerebellar ataxia and oculomotor disturbances, is responsible for around 30% of the cases previously classified as idiopathic.

Bilateral vestibulopathy.

Newly described subtypes of bilateral vestibulopathy are associated with cerebellar disorders and polyneuropathy.

Treatment

Antibiotic treatment with aminoglycosides is the most frequently determined cause of bilateral vestibulopathy (26). This class of drugs should therefore be used very sparingly, particularly since their ototoxic effect has a latency of several days.

Physical therapy with gait and balance training helps the patient adapt to the functional deficit by maximizing the potential for visual and sensorimotor compensation. This has been confirmed at least for unilateral impairment of vestibular function (20). Mere explanation of the cause and mechanism of BVP often leads to considerable relief with a decrease in subjective symptoms. Despite a multitude of visits to the doctor, BVP is usually diagnosed too late, which amplifies the patient’s symptoms.

Natural course

Observational studies of more than 80 patients for approximately 5 years showed no significant improvement in vestibular function in more than 80% of cases, regardless of etiology, course, sex, and age at first manifestation (27).

Menière’s disease

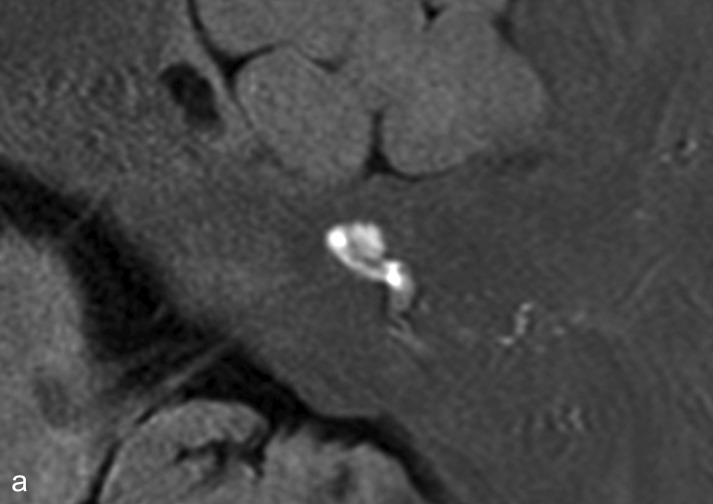

Typically, attacks of Menière’s disease are characterized by recurring postural vertigo persisting for a time ranging from minutes to hours and accompanied by hearing impairment, tinnitus, and a feeling of pressure in the affected ear. Occasionally the vertigo is preceded by amplified ear noises, increased ear pressure, or reduced acuity of hearing. Despite a large number of studies the etiology and pathophysiology of Menière’s disease remain incompletely elucidated. The pathognomonic histopathological finding is endolymphatic hydrops, which can now be visualized well on high-resolution MRI of the petrosal bone after transtympanic injection of gadolinium (Figure 1) (28). The attacks probably arise from the opening of pressure-sensitive cation channels and/or rupture of the endolymphatic membrane with increased potassium concentration in the perilymphatic space, which leads initially to excitation and then to depolarization of the axons.

Figure 1.

Endolymphatic hydrops as seen on high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging of the petrosal bone 24 h after transtympanic injection of gadolinium, which diffuses predominantly into the perilymphatic space.

a) The labyrinth of a healthy control: The cochlea and semicircular canals are visualized.

b) The labyrinth of a patient with Menière’s disease: the endolymphatic hydrops can be recognized by virtue of its lack of contrast medium uptake.

With kind permission by Robert Gürkov

Endolymphatic hydrops.

Endolymphatic hydrops in Menière’s disease can be visualized by MRI.

Treatment

The acute symptoms of vertigo, nausea, and vomiting can be ameliorated by means of antivertigo drugs (Table 2). To date, positive effects of prophylactic treatment to reduce the frequency of attacks have been reported for transtympanic instillation of gentamicin and of steroids and for long-term high-dose administration of betahistine (1, 29). Gentamicin takes effect by causing direct damage to vestibular type I hair cells. Two prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trials (e6, e7) have shown the efficacy of gentamicin, supported by a Cochrane review (30). The danger of treatment with aminoglycosides is the possibility of hearing damage. Transtympanic administration of glucocorticoids is increasing, although so far only one methodologically impeccable study has demonstrated an effect (31). Furthermore, a prospective randomized controlled trial showed that the frequency of vertigo attacks in refractory Menière’s disease was reduced much more by the transtympanic administration of low doses of gentamicin than by intratympanic dexamethasone (93% vs 61%) (32).

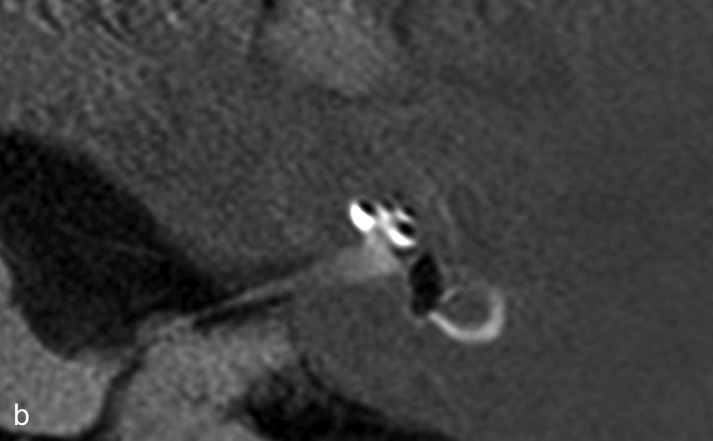

Meta-analyses demonstrate that betahistine—a weak H1 agonist and strong H3 antagonist—has a prophylactic effect on the frequency of attacks of Menière’s disease. Observation of treatment in 112 patients showed that high dosage of betahistine (3 × 48 mg/day) is significantly superior to 3 × 24 mg/day, particularly with long-term administration (12 months) (33). In a few individual cases the dosage was even gradually increased to 480 mg/day (34). Recent animal experiments seem to indicate that the mechanism of action of betahistine (Figure 2) (35) and its metabolites is improved blood flow in the inner ear. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter dose-finding study is currently being conducted to investigate the prophylactic action of betahistine hydrochloride on attack frequency and on vestibular and audiological function (BEMED, funded by the BMBF).

Figure 2.

The relationship between cochlear blood flow and betahistine hydrochloride dosage in an animal experiment (nonlinear regression curve; mean ± SD; * p < 0.05) and the calculated corresponding oral single doses (modified from [35]). The sigmoidal dose–effect curve correlates with the higher doses of up to 160 mg betahistine (red line) used clinically to prevent Menière’s disease

Treatment of Menière’s disease.

Long-term high-dose treatment with betahistine is apparently effective in preventing attacks of vertigo, but has to be investigated further in clinical trials.

Recurring vestibular drop attacks are extremely bothersome for patients with Menière’s disease and often result in injury. If high-dose treatment with betahistine fails to achieve any improvement, transtympanic gentamicin may be successful, provided the affected ear can be identified with sufficient certainty.

Natural course

Menière’s disease is initially unilateral; the frequency of attacks increases at first, then decreases. The longer the disease persists, the more likely it is to become bilateral. The rate of bilateral disease is around 15% in the early phase (up to 2 years), around 35% after 10 years, and up to 47% after 20 years (36). This represents an additional problem with gentamicin treatment. Initially patients are free of symptoms between episodes, but in the course of time they develop hearing impairment (not restricted to loss of low tones), tinnitus, and postural vertigo. Many patients experience a relatively benign course over the first 5 to 10 years, with attacks decreasing in frequency (36).

Recurring vestibular drop attacks.

These are extremely bothersome for patients with Menière’s disease and often result in injury.

Vestibular paroxysmia

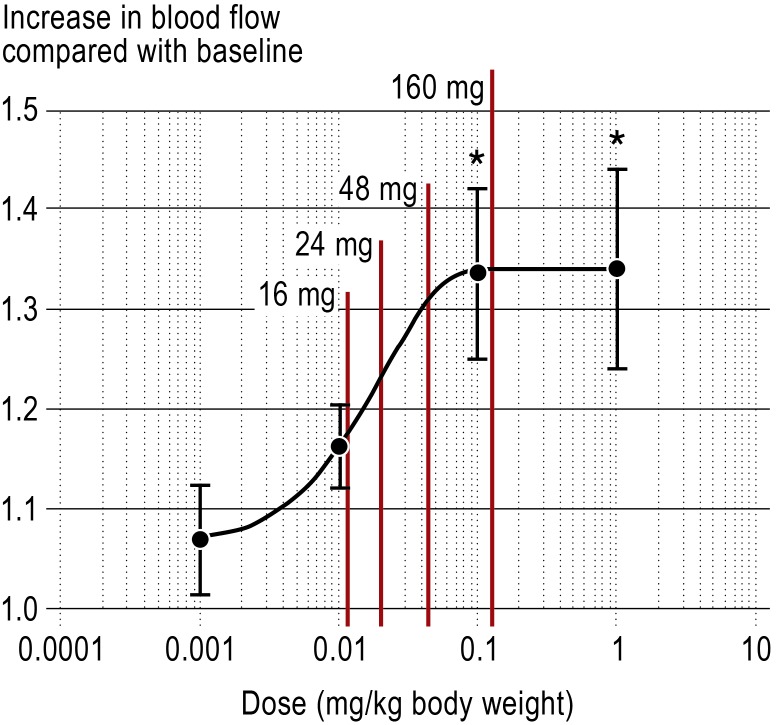

Analogously with trigeminal neuralgia, vestibular paroxysmia probably arises from neurovascular compression of the eighth cranial nerve in the vicinity of the brainstem (37, 38) (Figure 3) due to ephaptic cross-talk between partly demyelinized axons. The attacks in vestibular paroxysmia are typically short, lasting from seconds up to a few minutes, and consist of rotatory (occasionally postural) vertigo with or without ear symptoms (tinnitus and hearing impairment); an attack can often be provoked by prolonged hyperventilation (37, 39). In over 95% of cases high-resolution MRI of the brainstem, specifically a CISS (constructive interference in steady state) sequence, demonstrates vessel–nerve contact at the exit point of the eighth cranial nerve from the brainstem (38, 39, e8); this may also be seen in healthy controls, however, so the finding is not specific. The clinical presentation of vestibular paroxysmia has been defined more precisely in recent years, and the potential for successful treatment with carbamazepine has been shown (37, 39).

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging and intraoperative microscopy in a patient with right-sided vestibular paroxysmia

a) High-resolution MRI of the cerebellopontine angle depicting the contact between the vestibulocochlear nerve (N. vest.) and the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (constructive interference in steady state [CISS] sequence)

b) Time-of-flight (TOF) sequence for improved visualization of vessels; AICA, anterior inferior cerebellar artery

c) The vessel–nerve contact is also seen intraoperatively

d) Distinct compression of the vessel after removal of the vestibulocochlear nerve (circle) (modified from [38])

With kind permission by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Natural course of Menière’s disease.

Menière’s disease is initially unilateral; the frequency of attacks increases at first, then decreases. The longer the disease persists, the more likely it is to become bilateral.

Cause of vestibular paroxysmia.

Vestibular paroxysmia probably arises from neurovascular compression of the eighth cranial nerve in the vicinity of the brainstem.

Treatment

If the patient is suffering more than two strong attacks per month, low-dose treatment with carbamazepine 200–600 mg/day may be successful and may also help to confirm the diagnosis (37, 39). Phenytoin and valproic acid are alternatives for patients who do not tolerate carbamazepine. However, no prospective randomized controlled trials have yet been published for any of these substances.

Natural course

A study in which 32 patients were followed up for a mean period of 3 years showed that treatment with carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine achieved a persisting significant reduction in attacks to 10% of the initial frequency, as well as reducing attack intensity and duration (39).

Vestibular migraine

Vestibular migraine is the chameleon among the diseases featuring episodic vertigo, not only in the frequency and duration of attacks (usually minutes or hours, but sometimes up to days) but also in the form of vertigo (rotatory or postural) and in the accompanying symptoms (with or without headache; vestibular and/or oculomotor disorders) (e9). Most episodes of vestibular migraine include vertigo (40). Diagnosis is straightforward if the attacks are followed by headache or there is a history of other forms of migraine in the patient or members of his/her family, but more difficult in the approximately 30% of cases where headache and other symptoms of migraine are absent. Diagnosis is facilitated by the fact that over 60% of patients with vestibular migraine also display slight central oculomotor disorders such as gaze nystagmus, gaze saccades, or central positional nystagmus (e10, e11). Unsteady stance and gait with pathological nystagmus and positional nystagmus are often observed during an attack and can be attributed to either central or peripheral vestibular dysfunction.

Treatment

No prospective controlled treatment trials have been published to date. Nevertheless, in analogy to the treatment of migraine without aura the same principles are used that have already proved effective in the treatment of attacks and for migraine prophylaxis. The treatment of choice in migraine prophylaxis is administration of beta-blockers (e.g., metoprolol succinate at a dose of around 50–200 mg/day) for a period of 6 months. Alternatives are topiramate or valproic acid, which have also only been described in observational studies of small numbers of patients. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study is currently being conducted to investigate the prophylactic action of metoprolol on attack frequency (PROVEMIG, funded by the BMBF).

Vestibular migraine.

No prospective controlled trials of treatment for vestibular migraine have been published to date.

Natural course

In the course of a long-term evaluation of diagnostic criteria, the diagnosis was confirmed in the overwhelming majority of cases; half of the patients with a tentative diagnosis of vestibular migraine developed definitive migraine over a mean follow-up of 8 years (e12). As yet there are no valid prospective studies of attack frequency with and without prophylactic drug treatment.

Cerebellar vertigo syndromes and their treatment

Neurodegenerative and hereditary diseases of the cerebellum often lead to postural vertigo, associated with gait disorders and typical cerebellar oculomotor disorders (16) such as dysmetric saccades, gaze saccades, and gaze nystagmus as well as downbeat nystagmus. Clinical experience shows that these disorders are often the first sign that the postural vertigo is being caused by a cerebellar syndrome, especially if the patient has no ataxia of the extremities or speech disorder. Aminopyridines (potassium-channel blockers) have become established as a new pharmacological treatment option for the following symptoms of cerebellar diseases:

Downbeat nystagmus (8); the efficacy of 4-aminopyridine is supported by a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (e13)

Central positional nystagmus (9)

Episodic ataxia type 2 (10)

Gait disorders in cerebellar ataxia (11).

Either 4-aminopyridine (2–3 × 5 mg/day) or its slow-release form fampridine (1–2 × 10 mg/day) is used on an individual, off-label basis to treat cerebellar vertigo syndromes (e14, e15). Chlorzoxazone, an activator of calcium-dependent potassium channels, also leads to a reduction in downbeat nystagmus (e16). Finally, a recent observational study of 13 patients showed that the modified amino acid acetyl-DL-leucine (5g/day) exerts a significant effect on cerebellar ataxia after only one week (e16).

Aminopyridines, chlorzoxazone, and acetyl-DL-leucine.

These are new pharmacological treatment options for cerebellar diseases.

Further Information On Cme.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education.

Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquired only through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire. See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under “meine Daten” (“my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

The present CME unit can be accessed until 20 October 2013.

The CME unit “Growing up is hard—mental disorders in adolescence” (issue 25/2013) can be accessed until 22 September 2013.

The CME unit “The diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis” (issue 21/2013) can be accessed until 18 August 2013.

After consultation with the certifying body, the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education, answers b) and c) to question 5 of the CME unit “The diagnosis and treatment of generalized anxiety disorder” (issue 17/2013) will both be considered correct.

For issue 33–34/2013, we plan to offer the topic “Shortness of breath and cough in patients in palliative care.”

Please answer the following questions to participate in our certified Continuing Medical Education program. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

A 32-year-old man with osteomyelitis was treated with gentamicin. Three weeks after this treatment he noticed increasing unsteadiness of gait and postural vertigo while standing. On questioning he reports that objects around him appeared to move when he walked. The postural vertigo is more pronounced in darkness and on uneven surfaces. Clinical examination shows bilateral dysfunction of the vestibular system and a pathological tendency to fall down. What is the correct diagnosis?

Episodic ataxia type 2

Brainstem infarction

Bilateral vestibulopathy

Psychogenic vertigo

Visual vertigo

Question 2

A 48-year-old woman reports constantly recurring attacks of vertigo lasting for hours, associated with a feeling of pressure in the right ear, right-sided hearing impairment, and intermittent right-sided tinnitus. She says she has had about one attack a week over the past few months. Her hearing in the right ear has deteriorated. What is the diagnosis?

Vestibular migraine

Recurring otitis media

Vestibular paroxysmia

Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Menière’s disease

Question 3

A 68-year-old woman reports constant severe postural vertigo for the past 24 h. The onset was acute. Objects around her appear to move, and she tends to fall down to the left. Clinical examination reveals nystagmus beating to the right and a pathological result of the head impulse test when turning the head towards the left. There are no central oculomotor disorders. What is the correct diagnosis?

Vestibular neuritis

Ischemia in the area of the spinal cord

Wallenberg syndrome

Mesencephalic infarction

Visual vertigo

Question 4

An 80-year-old woman fell off her bicycle and hit her head on the ground. Next morning she experienced severe postural vertigo when she sat up in bed; the vertigo subsided when she stayed still. On questioning she states that the postural vertigo is provoked by changing the position of her head and the attacks last only a few seconds. What is the correct diagnosis?

Cervicogenic vertigo

Phobic vestibular vertigo

Vestibular migraine

Downbeat nystagmus syndrome

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Question 5

Which disease can be treated with aminopyridines?

Downbeat nystagmus

Vestibular neuritis

Menière’s disease

Bilateral vestibulopathy

Phobic vestibular vertigo

Question 6

Which symptoms or findings frequently occur in combination with bilateral vestibulopathy?

Vertigo while lying down

Degenerative diseases of the cerebellum

Perilymphatic fistula

Persisting rotatory vertigo

Headache

Question 7

What is the drug of choice for treating vestibular paroxysmia?

Dimenhydrinate

Carbamazepine

Diazepam

Aminopyridine

Acetazolamide

Question 8

How high, approximately, is the overall risk of recurrence in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo?

5%

15%

30%

50%

80%

Question 9

Which drug can be given to prevent the attacks in Menière’s disease?

Metoprolol

Betahistine

Carbamazepine

Topiramate

Dimenhydrinate

Question 10

A 48-year-old woman reports a 10-year history of vertigo attacks that occur at around monthly intervals and last for a number of hours. The attacks are sometimes accompanied by headache that seems to emanate from the neck. On physical examination you find a slight central oculomotor disorder. What is the diagnosis?

Multiple sclerosis

Vestibular paroxysmia

Recurring brainstem ischemia

Vestibular migraine

Degenerative cerebellar disease

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Strupp has received consulting fees from Abbott, Pierre-Fabre and Biogen Idec. He has received payments from Abbott, Biogen Idec, CSC, Henning Pharma, and GSK for preparation of scientific training courses.

Prof. Dieterich und Prof. Brandt declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Brandt T, Dieterich M, Strupp M. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin; 2012. Vertigo - Leitsymptom Schwindel. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strupp M, Brandt T. Diagnosis and treatment of vertigo and dizziness. Dtsch Arzteblatt Int. 2008;105:173–180. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuhauser HK. Epidemiology of vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:40–46. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328013f432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geser R, Straumann D. Referral and final diagnoses of patients assessed in an academic vertigo center. Front Neurol. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt T, Zwergal A, Jahn K, Strupp M. Integrated center for research and treatment of vertigo, balance and ocular motor disorders. Nervenarzt. 2009;80:875–886. doi: 10.1007/s00115-009-2812-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diener HC, Weimar C. 5th ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2012. Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strupp M, Thurtell MJ, Shaikh AG, Brandt T, Zee DS, Leigh RJ. Pharmacotherapy of vestibular and ocular motor disorders, including nystagmus. J Neurol. 2011;258:1207–1222. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5999-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strupp M, Schuler O, Krafczyk S, et al. Treatment of downbeat nystagmus with 3,4-diaminopyridine: a placebo-controlled study. Neurology. 2003;61:165–170. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078893.41040.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kremmyda O, Zwergal A, la FC, Brandt T, Jahn K, Strupp M. 4-Aminopyridine suppresses positional nystagmus caused by cerebellar vermis lesion. J Neurol. 2013;260:321–323. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6737-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strupp M, Kalla R, Claassen J, et al. A randomized trial of 4-aminopyridine in EA2 and related familial episodic ataxias. Neurology. 2011;77:269–275. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225ab07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schniepp R, Wuehr M, Neuhaeusser M, et al. 4-Aminopyridine and cerebellar gait: a retrospective case series. J Neurol. 2012;259:2491–2493. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6595-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong SH, Kim JS, Shin JW, et al. Decreased serum vitamin D in idiopathic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol. 2013;260:832–838. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6712-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gufoni M, Mastrosimone L, Di NF. Repositioning maneuver in benign paroxysmal vertigo of horizontal semicircular canal. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1998;18:363–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yacovino DA, Hain TC, Gualtieri F. New therapeutic maneuver for anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol. 2009;256:1851–1855. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandt T, Huppert D, Hecht J, Karch C, Strupp M. Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo: a long-term follow-up (6-17 years) of 125 patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126:160–163. doi: 10.1080/00016480500280140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strupp M, Hüfner K, Sandmann R, et al. Central oculomotor disturbances and nystagmus: a window into the brainstem and cerebellum. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:197–204. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strupp M, Zingler VC, Arbusow V, et al. Methylprednisolone, valacyclovir, or the combination for vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:354–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishman JM, Burgess C, Waddell A. Corticosteroids for the treatment of idiopathic acute vestibular dysfunction (vestibular neuritis) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008607.pub2. CD008607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strupp M, Arbusow V, Maag KP, Gall C, Brandt T. Vestibular exercises improve central vestibulospinal compensation after vestibular neuritis. Neurology. 1998;51:838–844. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hillier SL, McDonnell M. Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005397.pub3. 2 CD005397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandt T, Huppert T, Hüfner K, Zingler VC, Dieterich M, Strupp M. Long-term course and relapses of vestibular and balance disorders. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2010;28:69–82. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huppert D, Strupp M, Theil D, Glaser M, Brandt T. Low recurrence rate of vestibular neuritis: a long-term follow-up. Neurology. 2006;67:1870–1871. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244473.84246.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandt T, Schautzer F, Hamilton D, et al. Vestibular loss causes hippocampal atrophy and impaired spatial memory in humans. Brain. 2005;128:2732–2741. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zingler VC, Cnyrim C, Jahn K, et al. Causative factors and epidemiology of bilateral vestibulopathy in 255 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:524–532. doi: 10.1002/ana.21105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirchner H, Kremmyda O, Hüfner K, et al. Clinical, electrophysiological, and MRI findings in patients with cerebellar ataxia and a bilaterally pathological head-impulse test. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1233:127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szmulewicz DJ, Waterston JA, Halmagyi GM, et al. Sensory neuropathy as part of the cerebellar ataxia neuropathy vestibular areflexia syndrome. Neurology. 2011;76:1903–1910. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821d746e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zingler VC, Weintz E, Jahn K, et al. Follow-up of vestibular function in bilateral vestibulopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;79:284–288. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.122952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gürkov R, Flatz W, Louza J, Strupp M, Krause E. In vivo visualization of endolymphatic hydrops in patients with Meniere’s disease: correlation with audiovestibular function. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:1743–1748. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strupp M, Barndt T. Peripheral vestibular disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2013;26:81–89. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32835c5fd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pullens B, van Benthem PP. Intratympanic gentamicin for Meniere’s disease or syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008234.pub2. CD008234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garduno-Anaya MA, Couthino De TH, Hinojosa-Gonzalez R, Pane-Pianese C, Rios-Castaneda LC. Dexamethasone inner ear perfusion by intratympanic injection in unilateral Meniere’s disease: a two-year prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casani AP, Piaggi P, Cerchiai N, Seccia V, Franceschini SS, Dallan I. Intratympanic treatment of intractable unilateral Meniere disease: gentamicin or dexamethasone? A randomized controlled trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:430–437. doi: 10.1177/0194599811429432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strupp M, Huppert D, Frenzel C, et al. Long-term prophylactic treatment of attacks of vertigo in Meniere’s disease—comparison of a high with a low dosage of betahistine in an open trial. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:520–524. doi: 10.1080/00016480701724912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lezius F, Adrion C, Mansmann U, Jahn K, Strupp M. High-dosage betahistine dihydrochloride between 288 and 480 mg/day in patients with severe Meniere’s disease: a case series. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:1237–1240. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1647-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ihler F, Bertlich M, Sharaf K, Strieth S, Strupp M, Canis M. Betahistine exerts a dose-dependent effect on cochlear stria vascularis blood flow in Guinea pigs in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huppert D, Strupp M, Brandt T. Long-term course of Meniere’s disease revisited. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:644–651. doi: 10.3109/00016480903382808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandt T, Dieterich M. Vestibular paroxysmia: vascular compression of the eighth nerve? Lancet. 1994;343:798–799. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91879-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strupp M, von Stuckrad-Barre S, Brandt T, Tonn JC. Teaching NeuroImages: Compression of the eighth cranial nerve causes vestibular paroxysmia. Neurology. 2013;80 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318281cc2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hüfner K, Barresi D, Glaser M, et al. Vestibular paroxysmia: diagnostic features and medical treatment. Neurology. 2008;71:1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326594.91291.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, et al. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria : Consensus document of the Barany Society and the International Headache Society. Nervenarzt. 2013;84:511–516. doi: 10.1007/s00115-013-3768-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Kim JS, Oh SY, Lee SH, et al. Randomized clinical trial for geotropic horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2012;79:700–707. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182648b8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Kim JS, Oh SY, Lee SH, et al. Randomized clinical trial for apogeotropic horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2012;78:159–166. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823fcd26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Karlberg ML, Magnusson M. Treatment of acute vestibular neuronitis with glucocorticoids. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32:1140–1143. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182267e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Kim YH, Kim KS, Kim KJ, Choi H, Choi JS, Hwang IK. Recurrence of vertigo in patients with vestibular neuritis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131:1172–1177. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.593551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Arbusow V, Theil D, Strupp M, Mascolo A, Brandt T. HSV-1 not only in human vestibular ganglia but also in the vestibular labyrinth. Audiol Neurootol. 2000;6:259–262. doi: 10.1159/000046131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Stokroos R, Kingma H. Selective vestibular ablation by intratympanic gentamicin in patients with unilateral active Meniere’s disease: a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:172–175. doi: 10.1080/00016480410016621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Postema RJ, Kingma CM, Wit HP, Albers FW, Van Der Laan BF. Intratympanic gentamicin therapy for control of vertigo in unilateral Menire’s disease: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:876–880. doi: 10.1080/00016480701762458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Best Ch, Gawehn J, Krämer HH, et al. MRI and neurophysiology in vestibular paroxysmia: contradiction and correlation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305513. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Dieterich M, Brandt T. Episodic vertigo related to migraine (90 cases): vestibular migraine? J Neurol. 1999;246:883–892. doi: 10.1007/s004150050478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.von Brevern M, Zeise D, Neuhauser H, Clarke AH, Lempert T. Acute migrainous vertigo: clinical and oculographic findings. Brain. 2005;128:365–374. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.von Brevern M, Radtke A, Clarke AH, Lempert T. Migrainous vertigo presenting as episodic positional vertigo. Neurology. 2004;62:469–472. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106949.55346.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Radtke A, Neuhauser H, von BM, Hottenrott T, Lempert T. Vestibular migraine—validity of clinical diagnostic criteria. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:906–913. doi: 10.1177/0333102411405228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Claassen J, Spiegel R, Kalla R, et al. A randomised double-blind, cross-over trial of 4-aminopyridine for downbeat nystagmus—effects on slow phase eye velocity, postural stability, locomotion and symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013 Jun; doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304736. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Claassen J, Feil K, Bardins S, Teufel J, et al. Dalfampridine in patients with downbeat nystagmus—an observational study. J Neurol. 2013 Apr; doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6911-5. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Claassen J, Teufel J, Kalla R, Spiegel R, Strupp M. Effects of dalfampridine on attacks in patients with episodic ataxia type 2: an observational study. J Neurol. 2013;260:668–669. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Strupp M, Teufel J, Habs M, et al. Effects of acetyl-DL-leucine in patients with cerebellar ataxia: a case series. J Neurol. 2013 Jul; doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7016-x. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]