Abstract

Objectives

Acute respiratory distress syndrome develops commonly in critically ill patients in response to an injurious stimulus. The prevalence and risk factors for development of acute respiratory distress syndrome after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage have not been reported. We sought to determine the prevalence of acute respiratory distress syndrome after intracerebral hemorrhage, characterize risk factors for its development, and assess its impact on patient outcomes.

Design

Retrospective cohort study at two academic centers.

Patients

We included consecutive patients presenting from June 1, 2000, to November 1, 2010, with intracerebral hemorrhage requiring mechanical ventilation. We excluded patients with age less than 18 years, intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to trauma, tumor, ischemic stroke, or structural lesion; if they required intubation only during surgery; if they were admitted for comfort measures; or for a history of immunodefciency.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

Data were collected both prospectively as part of an ongoing cohort study and by retrospective chart review. Of 1,665 patients identified by database query, 697 met inclusion criteria. The prevalence of acute respiratory distress syndrome was 27%. In unadjusted analysis, high tidal volume ventilation was associated with an increased risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome (hazard ratio, 1.79 [95% CI, 1.13–2.83]), as were male sex, RBC and plasma transfusion, higher fluid balance, obesity, hypoxemia, acidosis, tobacco use, emergent hematoma evacuation, and vasopressor dependence. In multivariable modeling, high tidal volume ventilation was the strongest risk factor for acute respiratory distress syndrome development (hazard ratio, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.08–2.81]) and for inhospital mortality (hazard ratio, 2.52 [95% CI, 1.46–4.34]).

Conclusions

Development of acute respiratory distress syndrome is common after intubation for intracerebral hemorrhage. Modifiable risk factors, including high tidal volume ventilation, are associated with its development and in-patient mortality.

Keywords: acute lung injury, hemorrhagic stroke, mechanical ventilation, tidal volume, ventilator-induced lung injury

The development of neurogenic pulmonary edema after a neurologic insult has been recognized for over a century (1). Neurologic injury leads to systemic inflam-mation, increases pulmonary vascular hydrostatic pressure and endothelial permeability, and potentiates pulmonary inflammation (2–5). The histopathologic features observed in patients who die with neurogenic pulmonary edema are virtually identical to those observed with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (6, 7), and many have suggested that these two entities are pathophysiologically identical (8, 9).

ARDS occurs in up to 20–25% of cases of spontaneous sub-arachnoid hemorrhage and traumatic brain injury (TBI) and is a major driver of morbidity and cost in these patients (4, 10– 14). Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is arguably the most devastating form of neurologic injury, with 1-month mortality rates in excess of 40% and death or severe disability rates exceeding 75% (15). In contrast to patients presenting with TBI, patients with ICH tend to be older, have more medical comorbidities, and do not have concomitant multisystem injury, making it difficult to extrapolate findings from studies of TBI patients to this population. Patients with ICH may be aggressively ventilated to maximize cerebral oxygenation and avoid elevations in intracranial pressure due to hypercarbia, but the impact of these strategies on the lungs and overall outcomes is unclear. To our knowledge, the prevalence, risk factors, and impact of ARDS after ICH have not been reported.

In this study, we evaluated the prevalence of ARDS in a large, multicenter cohort of patients with ICH who required mechanical ventilation. We hypothesized that ARDS would be common, with a prevalence of 20–25%, similar to that observed in other neurologic critical illnesses. We also hypothesized that risk factors known to predispose to ARDS in other patient populations, particularly high tidal volume ventilation, would be significantly associated with ARDS development in our cohort and that ARDS would be an independent predictor of inhospital mortality and worse neurologic outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a multicenter retrospective cohort study including patients at two academic referral centers (Massachusetts General Hospital [MGH] and Brigham and Women’s Hospital [BWH]) from June 1, 2000, to November 1, 2010. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board that covers both centers.

Data Collection

At MGH, we identified potentially eligible patients from an ongoing prospective registry of consecutive patients with ICH that has been previously described (16). At BWH, potentially eligible patients were identified via query of a centralized electronic data registry. This database includes demographics, diagnoses, procedures, inpatient pharmacy data, laboratory and radiology results, as well as electronic notes for the entire study period. We searched for all patients with ICD-9 codes associated with ICH (431.x: ICH; 439.2: unspecified intracranial hemorrhage; 853.0: hematoma, brain, nontraumatic; 459.0: nontraumatic hemorrhage) and procedure codes for mechanical ventilation (CPT 31500: endotracheal intubation; CPTs 94002, 94003, 94656, and 94657: mechanical ventilation assistance; ICD-9 96.x continuous mechanical ventilation). A physician then reviewed each medical record for inclusion and exclusion criteria.

We included patients in the current study if they presented to the emergency department with ICH and required mechanical ventilation prior to hospital day 5. Patients were excluded for age less than18 years; ICH secondary to head trauma, ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic transformation, brain tumor, vascular malformation, or vasculitis; if they were mechanically ventilated only during an operative intervention; if they were declared brain dead or their goals of care were made comfort measures only prior to admission; or for a history of significant immunodeficiency including human immunodeficiency virus infection, cytotoxic chemotherapy within 1 month of admission, leukemia, or common variable immunodeficiency.

We performed a structured chart review using REDCap, an electronic data capture tool supported by the National Institutes of Health (17). We collected data on each patient until the development of ARDS, death, extubation, or the end of hospital day 5. We chose this cutoff to minimize confounding by the development of ARDS due to a complication of critical illness rather than attributable to the ICH itself (e.g., ARDS secondary to ventilator-associated pneumonia). Trained clinical research coordinators abstracted clinical data under the supervision of a physician. All chest radiographs were reviewed by a board-certified radiologist.

Exposure, Covariates, and Outcomes

The primary exposure of interest was high tidal volume ventilation. We recorded each patient’s height and used it to calculate predicted body weight (PBW) using standard techniques (18). If a patient’s height was not documented, we imputed it from available data including age, race, sex, and weight using previously described techniques (19). To examine the sensitivity of the imputed data, we compared the results including and excluding patients whose heights were imputed. All ventilator settings were transcribed from respiratory therapy flow sheets. During the study period, standard practice at both hospitals was for respiratory therapists to record ventilator settings at least every 4 hours. We quantified exposure to high tidal volume ventilation by calculating the fraction of total ventilated time spent at a tidal volume > 8 mL/kg. As a sensitivity analysis, we also explored the impact when the threshold was changed to 10 mL/kg and 12 mL/kg PBW. In multivariable models, we used the threshold of 8 mL/kg PBW.

We recorded baseline clinical characteristics on all patients including age, sex, date of presentation, site of presentation, and whether the patient was transferred from an outside facility to the site of enrollment. We recorded laboratory values and medical comorbidities, as defined in the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE-II) scoring system (20), and calculated a modified APACHE-II score for each patient. In this modified score, we did not assign points for decreased Pao2:Fio2 ratio as this is a criterion for ARDS, our outcome of interest. We recorded disease-specific markers of severity including Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, hematoma size, infratentorial location of hemorrhage, and intraventricular extension, which are established predictors of mortality in patients with ICH (21). For patients intubated during their initial neurologic assessment, we derived the verbal component of the GCS score from the motor and eye component using previously described methods to calculate a numeric total GCS score (22). At BWH, a neurologist determined hematoma volumes from CT scans using ABC/2, and at MGH, we calculated these volumes using computerized planimetry as previously described (23). We recorded additional baseline characteristics known to modify the risk of ARDS in high-risk populations, including premorbid diabetes, use of tobacco, statins, steroids, aspirin, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), obesity (body mass index > 30), hypoalbuminemia (<2.4 mg/dL), tachypnea (respiratory rate >30 breaths/min), hypoxemia on hospital presentation (initial oxygen saturation < 95%), acidosis (arterial pH < 7.35), or need for emergent hematoma evacuation (24–26).

We abstracted clinical data in the emergency department and for each ICU day from electronic records and nursing flow sheets including initial, minimum, and maximum vital signs and WBC count; crystalloid and blood product administration, urine output, and total daily fluid balance; vasopressor dependence; microbiology culture data; and all arterial blood gas (ABG) samples. Because intracranial pressure was not measured in all patients, we modeled maximum intracranial pressure (<20 mm Hg, >20 mm Hg or not recorded) and minimum cerebral perfusion pressure (<60 mm Hg, >60 mm Hg or not recorded) as categorical variables. We calculated the daily burden of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) by assigning points based on standard criteria (heart rate > 90, respiratory rate > 20 or Paco2 < 35 mmHg, temperature > 38°C or < 36°C, and WBC count < 4K or > 12K) and summing the daily scores. At MGH, the use and date of “do not resuscitate” or “comfort measures only” orders were prospectively recorded. We were unable to retrospectively ascertain these data with high fidelity at BWH, so did not include these data in analysis.

Finally, we recorded outcomes for each patient, including inhospital mortality, Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score at discharge, and need for tracheostomy or percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement.

Identifying Patients With ARDS

Initially, we defined acute lung injury (ALI) based on the consensus definitions current at the time of the study’s inception (27) and then updated our definition to reflect the current Berlin Definition, as outlined below (28). We classified patients as having ARDS if they met all of the following criteria within a 24-hour period: 1) diffuse, bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph interpreted by a blinded, attending radiologist; 2) at least two consecutive ABG samples with a Pao2:Fio2 ratio < 300 mm Hg; and 3) no evidence of left atrial hypertension. If a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) was placed, absence of left atrial hypertension was defined as a pulmonary artery occlusion pressure <18mmHg. Because PACs were rarely placed, we defined a patient without a PAC as having no left atrial hypertension as follows: 1) if an echocardiogram was performed, it demonstrated normal systolic (ejection fraction > 45%) and diastolic (E:E′ < 15 or based on subjective assessment by the interpreting cardiologist) functions; and 2) no brain natriuretic peptide level was elevated > 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (29); and 3) no clinical impression of CHF was documented in daily progress or consult notes.

After we conducted our initial analysis, the Berlin Definition of ARDS was published (28). Our initial classification of ALI paralleled the Berlin Definition of “mild ARDS” except for the requirement of at least 5 cm H2O of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) in addition to a Pao2:Fio2 ratio < 300 mm Hg to meet the oxygenation criterion. We had decided a priori to record all ventilator settings for the duration of the study period, including PEEP. Thus, we were able to re-analyze our data using the Berlin Definition of mild ARDS and report all results in accordance with this definition.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive analyses to examine population characteristics and determine the prevalence of ARDS in our cohort. We summarized baseline demographics and clinical characteristics using mean ±SD for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. We selected biologically plausible covariates a priori, as outlined above, and performed unadjusted analysis to determine which were significantly associated with the development of ARDS. Variables that were recorded daily were considered time-varying covariates: we used accumulated values for exposure to blood products, burden of systemic inflammatory response inflammation, and fluid balance; the highest value up to day for intracranial pressure and the lowest value up to day for cerebral perfusion pressure; and the daily status for vasopressor dependence. We used Cox proportional hazard models to examine the relationship between time to developing ARDS (within the first 5 days of hospitalization) and potential predictors. To avoid overfitting, only those associated with ARDS at a significance level of p < 0.1 in unadjusted analysis were included in the multivariable regression analysis. Next, we conducted a multivariable regression analysis to compare outcomes between patients with ARDS development and those without ARDS development. We report associations with a significance level of p less than 0.05 from the multivariable regression model.

To assess the impact of ARDS on patient outcomes, we compared the population of patients with ARDS development with those without ARDS development. In particular, we compared the mortality rates, neurologic function at hospital discharge (GOS, treated as an ordinal variable), and rates of tracheostomy and percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement. We used chi-squared tests for dichotomized outcomes and Cochran-Armitage trend test to detect location shift for ordinal outcomes. Finally, we constructed a multivariable logistic model including variables associated with mortality in unadjusted analysis at a significance level of p less than 0.1 and reported those with a significance level of p less than 0.05 from the multivariable model.

RESULTS

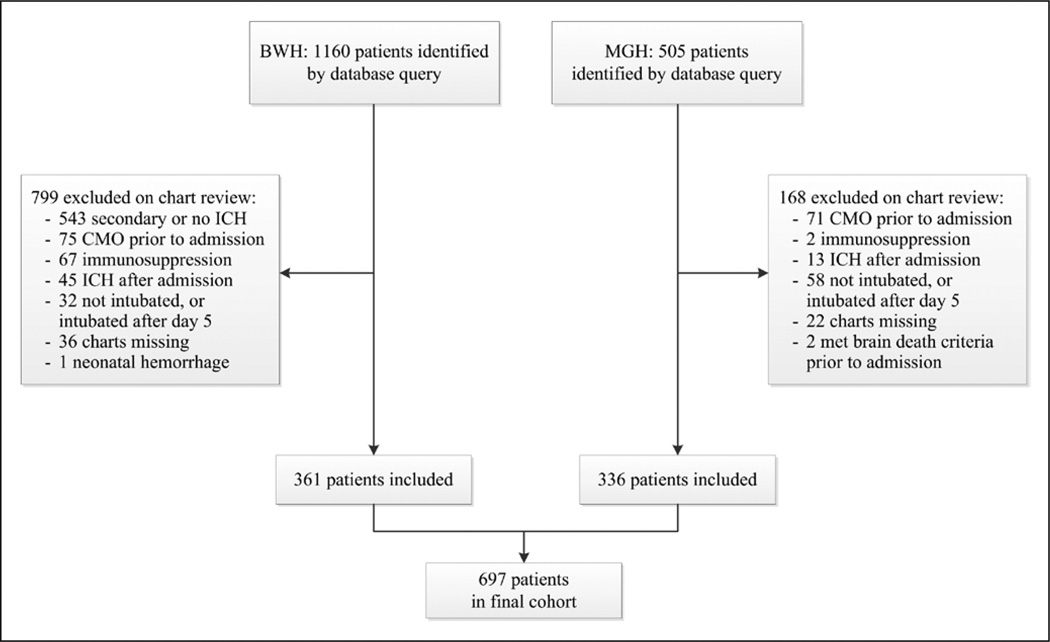

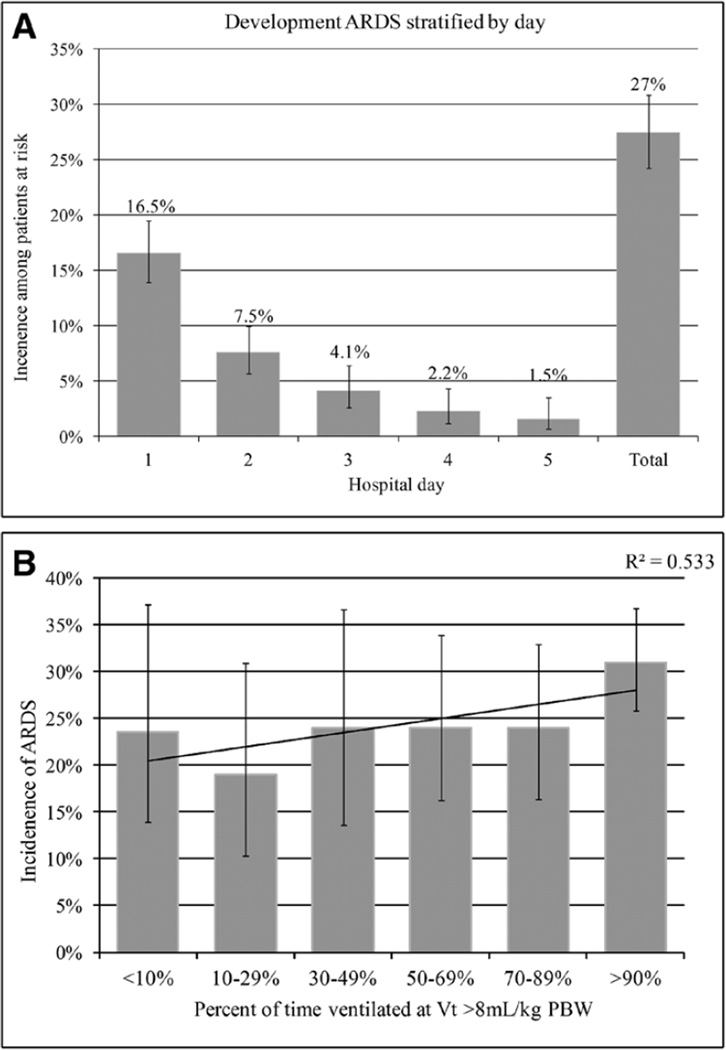

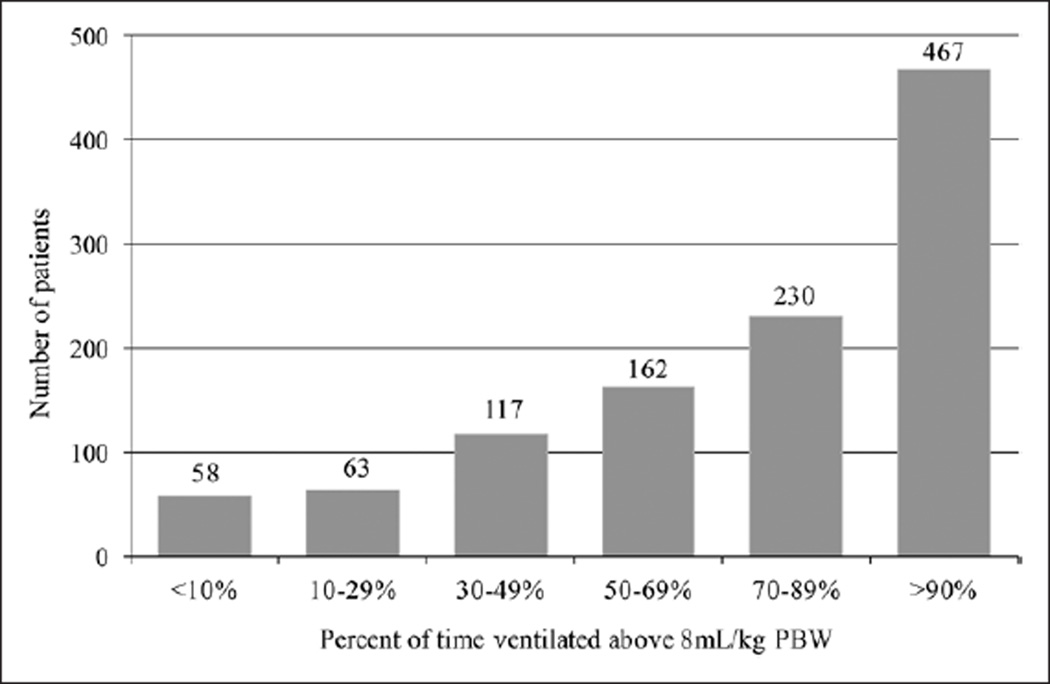

Our initial database query identified 1,641 potentially eligible patients. After chart review and applying exclusion criteria, 697 patients were left in the final cohort (Fig. 1). Demographics are shown in Table 1. The overall prevalence of ARDS was 27% (95% CI, 24–31%), and the majority of patients with ARDS development did so in the first two hospital days (Fig. 2A). All patients who met our initial definition of ALI were ventilated with at least 5 cm H2O of PEEP and also met the Berlin Definition of ARDS (28). The median percent of time ventilated at a tidal volume greater than 8 mL/kg was 70% (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Selection process for patients included in the fnal cohort. ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage, CMO = comfort measures only, BWH = Brigham and Women’s Hospital, MGH = Massachusetts General Hospital..

TABLE 1.

Demographics, Baseline Characteristics and Unadjusted Associations With Development of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

| Characteristic | Overall (n= 697) |

No ARDS (n= 506) |

ARDS (n= 191) |

Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr)a | 69 ± 13 | 70 ± 13 | 66 ± 14 | 0.87 (0.80–0.96) | 0.004 |

| Male | 323 (53) | 201 (48) | 112 (64) | 1.65 (1.25–2.16) | <0.001 |

| Year of presentation | |||||

| 2009–2011 | 160 (23) | 122 (24) | 38 (20) | Ref | |

| 2006–2008 | 259 (37) | 191 (38) | 68 (36) | 1.36 (0.87–2.14) | 0.27 |

| 2003–2005 | 211 (30) | 145 (29) | 66 (35) | 1.30 (0.81–2.08) | 0.47 |

| 2000–2002 | 67 (10) | 48 (10) | 19 (10) | 1.05 (0.55–1.98) | 0.61 |

| Transferred | 200 (33) | 132 (48) | 68 (36) | 1.15 (0.88–1.51) | 0.30 |

| Intubation timing | |||||

| Prior to arrival | 373 (61) | 268 (64) | 105 (55) | Ref | |

| In the emergency department | 184 (30) | 121 (29) | 62 (33) | 1.25 (0.94–1.66) | 0.13 |

| After admission | 53 (9) | 29 (7) | 24 (13) | 1.49 (1.01–2.21) | 0.045 |

| Disease severity | |||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale score | |||||

| 3–4 | 157 (26) | 117 (28) | 40 (21) | Ref | |

| 5–12 | 317 (52) | 216 (52) | 101 (53) | 0.86 (0.61–1.20) | 0.37 |

| 13–15 | 103 (17) | 66 (16) | 37 (19) | 0.74 (0.49–1.11) | 0.15 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage volume | |||||

| <30 mL | 253 (42) | 157 (38) | 96 (50) | Ref | |

| 30 to <60 mL | 121 (20) | 83 (20) | 38 (20) | 0.81 (0.57–1.14) | 0.22 |

| 60 to <90 mL | 74 (13) | 51 (12) | 23 (12) | 0.82 (0.54–1.25) | 0.35 |

| ≥ 90 mL | 102 (17) | 88 (21) | 14 (7) | 0.38 (0.22–0.66) | <0.001 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 136 (22) | 91 (22) | 45 (24) | 0.95 (0.70–1.30) | 0.76 |

| Infratentorial bleed | 43 (7) | 29 (7) | 14 (7) | 1.08 (0.68–1.67) | 0.77 |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score | 21±6 | 21±6 | 20±6 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.54 |

| Risk modifers at time of presentation | |||||

| Obesity | 129 (21) | 61 (15) | 68 (36) | 2.10 (1.31–2.74) | <0.001 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.89 (0.63–5.68) | 0.25 |

| Tachypnea | 17 (3) | 7 (2) | 10 (5) | 2.32 (1.33–4.05) | 0.003 |

| Hypoxemia | 124 (20) | 63 (15) | 61 (32) | 2.05 (1.57–2.68) | <0.001 |

| Acidosis | 65 (11) | 37 (9) | 28 (15) | 1.52 (1.05–2.25) | 0.03 |

| Tobacco use | 83 (14) | 49 (12) | 34 (18) | 1.45 (1.04–2.03) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 145 (24) | 97 (23) | 48 (25) | 1.13 (0.83–1.52) | 0.44 |

| Aspirin use | 206 (34) | 148 (35) | 58 (30) | 0.86 (0.64–1.14) | 0.29 |

| Statin use | 174 (29) | 121 (29) | 53 (28) | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.94 |

| Emergent hematoma evacuation | 75 (12) | 42 (10) | 33 (17) | 1.44 (1.02–2.02) | 0.037 |

| Inpatient course | |||||

| Percent of time ventilated above threshold tidal volume | |||||

| >8 mL/kg PBW | 70±34 | 68±37 | 74±33 | 1.79 (1.13–2.83) | 0.013 |

| >10 mL/kg PBW | 33±36 | 30±33 | 42±39 | 2.11 (1.46–3.04) | <0.001 |

| >12 mL/kg PBW | 12±24 | 10±22 | 12±27 | 1.91 (1.18–3.09) | 0.009 |

| Transfusionb | |||||

| Packed RBC (mL) | 80±300 | 56±226 | 113±415 | 1.23 (1.15–1.31) | <0.001 |

| Fresh frozen plasma (mL) | 306±656 | 262±574 | 401±802 | 1.07 (1.03–1.10) | <0.001 |

| Platelets (mL) | 111±279 | 116±294 | 98±337 | 1.062 (0.90–1.1.25) | 0.46 |

| Total fuid balance (L)c | 1.2±2.4 | 1.2±2.5 | 1.2±2.2 | 1.14 (1.06–1.24) | 0.001 |

| Do not resuscitate or comfort measures onlyd | 30 (4.3) | 23 (7.8) | 7 (9.9) | 2.72 (0.91–8.08) | 0.07 |

| Systemic infammatory response syndrome burden | 5±4 | 6±4 | 4±5 | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 0.35 |

| Minimum cerebral perfusion pressure (mm Hg) | 55±14 | 53±14 | 58±14 | 0.99 (0.93–1.04) | 0.67 |

| Maximum intracranial pressure (mm Hg) | 22±16 | 24±17 | 17±12 | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 0.11 |

| Vasopressor dependence | 97 (16) | 57 (14) | 40 (21) | 1.60 (1.17–2.19) | 0.003 |

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, PBW = predicted body weight.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Hazard ratio is expressed per decade.

Hazard ratio is expressed per unit of blood product transfused.

Hazard ratio is expressed per liter of fluid.

Data available and reported only for the subgroup of patients at MGH.

Figure 2.

A, Development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) stratifed by hospital day with 95% CIs. B, Development of ARDS stratifed by exposure to high tidal-volume ventilation with 95% CIs.

PBW = predicted body weight.

Figure 3.

Patients categorized by percent of time ventilated at a tidal volume greater than 8 mL/kg predicted body weight (PBW).

In our unadjusted analysis, high tidal volume ventilation was a significant risk factor for development of ARDS when modeled using a threshold of 8 mL/kg (Table 1; Fig. 2B). The magnitude of this association was greater at the 10 mL/kg and 12 mL/kg thresholds. We observed a dose–response relationship, whereby every 10% increase in time ventilated above a tidal volume of 8 mL/kg was significantly associated with an increased risk of ARDS (hazard ratio [HR], 1.06 [95% CI, 1.01–1.15]). Additional modifiable risk factors associated with ARDS development were exposure to packed RBCs (PRBCs) (HR, 1.2 3 per unit [95% CI, 1.15–1.31]), fresh frozen plasma (FFP) (HR, 1.07 per unit [95% CI, 1.03–1.10]), and higher total fluid balance (HR, 1.14 per liter [95% CI, 1.03–1.24]). Markers of disease severity including APACHE-II score, burden of SIRS, initial GCS score, hematoma volume, intraventricular extension, or infratentorial ICH location were not associated with ARDS risk. We also abstracted blood and sputum culture results for analysis. However, they were inconsistently obtained, and the rates of positive cultures were inadequate to meaningfully include these as covariates in our analysis. When we repeated our analysis excluding patients in whom height was imputed, our findings were unchanged (data not shown).

In the multivariable analysis, tidal volume remained a significant independent risk factor for development of ARDS (HR, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.08–2.81]) as did male sex, obesity, hypoxemia, exposure to PRBCs and FFP, higher total fluid balance, and vasopressor dependence (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Multivariable Model of Risk Factors for Development of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

| Characteristic | Multivariable Hazard Ratio | p |

|---|---|---|

| Tidal volume >8 mL/kg | 1.74 (1.08–2.81) | 0.02 |

| Male | 1.70 (1.27–2.28) | 0.02 |

| Vasopressor dependence | 1.70 (1.24–2.24) | 0.001 |

| Obesity | 1.67 (1.25–2.24) | <0.001 |

| Hypoxemia at presentation | 1.59 (1.18–2.10) | <0.001 |

| Packed RBC exposure (per unit) | 1.20 (1.13–1.28) | <0.001 |

| Fluid balance (per liter) | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) | 0.01 |

| Fresh frozen plasma exposure (per unit) | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 0.03 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage volume | ||

| <30 mL | Ref | |

| 30 to <60 mL | 0.81 (0.57–1.14) | 0.23 |

| 60 to <90 mL | 0.72 (0.47–1.11) | 0.14 |

| ≥90 mL | 0.41 (0.24–0.71) | 0.001 |

The overall inhospital mortality in our cohort was 67% (95% CI, 63–70%). In the unadjusted analysis, development of ARDS was associated neither with an increased risk of death in hospital nor with neurologic outcome at hospital discharge, or need for tracheostomy or percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement (Table 3). In the multivariable analysis, independent predictors of mortality were exposure to high tidal volume ventilation (HR, 2.52 [95% CI, 1.46–4.34]) and premorbid aspirin use (HR, 1.61 [95% CI, 1.08–2.39]), whereas higher burden of SIRS was associated with a reduced risk of mortality (HR, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.91–0.99]) (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Unadjusted Patient Outcomes

| Outcome | ARDS (n= 191) | No ARDS (n= 419) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhospital mortality | 128 (67%) | 289 (69%) | 0.63 |

| Glasgow Outcome Score | 0.46 | ||

| 1: Death | 128 (67%) | 289 (69%) | |

| 2: Vegetative | 5 (3%) | 19 (5%) | |

| 3: Severe disability | 52 (27%) | 94 (22%) | |

| 4: Mild disability | 6 (3%) | 13 (3%) | |

| 5: No disability | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Tracheostomy placement | 31 (16%) | 55 (13%) | 0.31 |

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome.

TABLE 4.

Multivariable Model of Risk Factors for Inhospital Mortality

| Characteristic | Multivariable Hazard Ratio | p |

|---|---|---|

| Tidal volume >8 mL/kg | 2.52 (1.46–4.34) | <0.001 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 1.00 (0.66–1.51) | 0.99 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score at presentation | ||

| 13–15 | Ref | |

| 5–12 | 0.85 (0.52–1.40) | 0.54 |

| 3–4 | 1.69 (0.94–3.03) | 0.08 |

| Steroid use | 0.65 (0.17–2.56) | 0.54 |

| Aspirin use | 1.61 (1.08–2.39) | 0.02 |

| Daily burden of systemic inflammatory response syndrome | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | 0.04 |

DISCUSSION

Development of ARDS was common in this cohort of patients with ICH requiring mechanical ventilation, with an overall prevalence of 27% (95% CI, 24–31%). This is similar to the rate of 20–25% observed in studies of ARDS development after subarachnoid hemorrhage and TBI (4, 10–12), and 35% reported in a mixed cohort of neurologically ill patients (30). Importantly, this rate is also comparable with that observed in other conditions traditionally viewed as “high risk” for developing lung injury, including sepsis, trauma, and aspiration (31). Many of the risk factors for ARDS in this cohort have previously been observed in non-neurologically ill patient populations. These include nonmodifiable risk factors such as obesity (32), hypoxemia (24), acidosis (33), tobacco use (34), emergent surgery (35), and vasopressor dependence (31).

Of greater interest are the potentially modifiable risk factors we identified, including high tidal volume ventilation, higher total fluid balance, and transfusion of PRBCs and FFP. In both our unadjusted and controlled multivariable models, high tidal volume ventilation was the single greatest risk factor for development of ARDS. Exposure to high tidal volume ventilation was common, with patients ventilated at a tidal volume above 8 mL/kg, a median of 70% of the time. Importantly, exposure to high tidal volume ventilation was also an independent risk factor for mortality in controlled, multivariable analysis. Our findings add to a growing body of literature that has suggested that high tidal volume ventilation is an important risk factor for development of ARDS in patients with a predisposing condition, rather than simply a risk factor for mortality in established ARDS (4, 36–38). Patients with ICH and other neurologic critical illnesses may be managed with more aggressive ventilator settings than in other diseases, as providers seek to protect the brain by avoiding hypercapnea and maximizing oxygenation. These strategies may lead to an increased rate of ARDS (4), and prospective studies are needed to determine the equipoise between lung and cerebral protections.

Higher total fluid balance leads to increased extravascular lung water and reduced pulmonary compliance, which increases the pressure required to deliver any given tidal volume and the potential for ventilator-induced lung injury (39, 40). In addition to contributing to a positive fluid balance, exposure to blood products leads directly to systemic immunomodulation and inflammation mediated by donor leukocytes, soluble donor-derived inflammatory mediators, and lipid debris (41, 42). This may potentiate pulmonary injury in a susceptible host or lead directly to transfusion-related ARDS (43–45). Because we did not record the indication for transfusion or clinical parameters such as hemoglobin or international normalized ratio at the time of transfusion, we were unable to judge the relative necessity of each transfusion or to determine optimal thresholds for administration of these products.

Interestingly, unlike in previous studies (46), transfusion of platelets was not a risk factor for development of ARDS in our cohort, despite the strong effect we observed with exposure to other blood products. At the two institutions in this study, it is common practice to transfuse platelets in ICH patients with a history of antiplatelet use. Aspirin and other antiplatelet agents may reduce the prevalence of ARDS by preventing platelet aggregation and downstream inflammation (25, 26), and the high co-incidence of these two exposures may have prevented us from detecting a harmful effect of platelet transfusion.

Male sex was a strong risk factor for ARDS in both unadjusted and multivariable analyses. This has been observed in some cohorts of patients with ARDS (24), although other studies have demonstrated that women frequently receive higher tidal volume ventilation and therefore may be at higher risk for ARDS than men (37, 47). Preclinical data suggest that exogenous estrogen may reduce lung inflammation and be protective against development of ARDS (48, 49); the number of women in our cohort receiving sex hormone replacement therapy is unknown and may partially explain this phenomenon in our cohort.

Neurologically ill patients are at increased risk of aspiration leading to pneumonitis or pneumonia, which may progress to ARDS. We could not reliably determine the occurrence of aspiration retrospectively, particularly because the majority of our cohort was intubated before arrival to the hospital. Lower GCS score on presentation was not associated with an increased risk of ARDS, which may suggest that aspiration may did not contribute significantly to development of ARDS in our cohort. However, lower GCS score does not necessarily indicate increased risk for aspiration (50, 51). Thus, we are unable to determine the contribution of aspiration to the prevalence of ARDS in our cohort.

Increased age was also associated with reduced risk of ARDS in our cohort. It may be that providers may less aggressively test these patients or move more quickly to limitations in goals of care. Because our determination of ARDS was dependent on providers’ decisions to order ABGs and chest imaging, less-aggressive testing would impair our ability to detect the true disease prevalence. Similarly, patients with the largest hematoma volumes (>90 mL) appeared to be at lower risk of development of ARDS. We hypothesize that less-aggressive testing of these sickest patients may have impaired our ability to detect the true prevalence of ARDS. The use of “do not resuscitate” or “comfort measures only” orders did not affect the prevalence of ARDS in the subgroup of patients at MGH where these data were prospectively recorded. However, the extent to which these orders adequately capture providers’ conscious or unconscious views of medical futility or tendency to test less aggressively (as opposed to families’ wishes or other unmeasured factors), is unknown.

ARDS is a major contributor to mortality in diverse patient populations, including neurologically ill patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage or TBI (4, 10–14, 18). We did not observe a direct association between ARDS and mortality, worse neurologic outcome, or tracheostomy or percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement. Mortality among patients with ICH is higher than in many other critical illnesses (15) and in our cohort was 67%. Thus, it may be that brain injury is such a profound driver of mortality in these patients that complications such as ARDS exert little additional effect. Alternatively, it may be that some patients who met criteria for ARDS actually exhibited a different cause of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, so-called neurogenic pulmonary edema. A majority of our cohort met criteria for ARDS by hospital day 2, somewhat earlier than expected for extrapulmonary sources of ARDS (52), which may support the contribution of such a distinct pathophysiologic entity. This may explain why we did not detect the expected association of ARDS with increased mortality in our cohort.

Another explanation may be that because mortality associated with ARDS has decreased dramatically in the era of lung protective ventilation (53), it may be that prompt recognition of the development of ARDS in our cohort led to the implementation of lung-protective strategies which minimized its impact. Finally, it may also be that care limitations are used more frequently in ICH than in other diseases, confounding our analyses. Because our ability to detect ARDS was contingent on testing ordered at the discretion of the treating physician, limitations in care might have reduced our ability to detect ARDS in the sickest patients. Importantly, we found that exposure to high tidal volume ventilation was a strong independent risk factor for mortality. Thus, it may be that high tidal volume ventilation can be viewed as a surrogate for development of ARDS that is resistant to such bias.

In this work, we analyzed a large cohort of patients at two academic medical centers, who presented over a 10-year period. Our findings parallel the results of other studies of ARDS in neurologically and non-neurologically ill patient populations, giving our results external validity. However, our work was limited by the retrospective determination of ARDS development. Because our ability to detect the outcome was limited by providers’ decisions to order diagnostic testing, factors such as limitations in goals of care may have reduced our ability to detect ARDS in the most severely injured patients, leading to a falsely low prevalence. Few patients in our cohort had a PAC placed, so we determined the presence or absence of left atrial hypertension based on other available data and may have misclassified some cases of cardiogenic pulmonary edema as ARDS. However, with the decline in PAC use, the criteria we selected a priori to determine the presence of left atrial hypertension have become widely accepted and are in line with recent consensus guidelines (54).

CONCLUSIONS

Our data show that development of ARDS after ICH is common and that modifiable risk factors identified in other patient populations are also relevant to these patients. High tidal volume ventilation is a strong and modifiable risk factor, as are transfusion of PRBCs and FFP, and higher total fluid balance. Exposure to high tidal volume ventilation is also an independent risk factor for in-patient mortality. Additional randomized, controlled trials are necessary to determine the equipoise between strategies designed to optimize cerebral hemodynamics and oxygenation and those designed for lung protection.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by a grant from the Emergency Medicine Foundation/ Emergency Medicine Resident’s Association, the Wuerz Award from the Department of Emergency Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and by the National Institutes of Health (R01NS073344, R01NS059727, and 5K23NS059774).

Dr. Hess has consulted for Philips Respironics, ResMed, Breathe Technology, and Pari. Dr. Greenberg has consulted for Hoffman La-Roche, received grants 5R01AG026484–08 and 5R01NS070834–03, and received payment for lectures from U of Texas-Grand Rounds. Dr. Rosand has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Goldstein has received grant support from the Mass Medical Society, the National Institutes of Health and NINDS. He has consulted for CSL Behring.

Footnotes

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shanahan WT. Acute pulmonary edema as a complication of epileptic seizures. NY Med J. 1908;54:54–56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu S, Fang CX, Kim J, et al. Enhanced pulmonary inflammation following experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Exp Neurol. 2006;200:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott L, McClain CJ, Gillespie M, et al. Cytokines and metabolic dysfunction after severe head injury. J Neurotrauma. 1994;11:447–472. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mascia L, Zavala E, Bosma K, et al. Brain IT group: High tidal volume is associated with the development of acute lung injury after severe brain injury An international observational study. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1815–1820. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275269.77467.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dziedzic T, Bartus S, Klimkowicz A, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage triggers interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 release in blood. Stroke. 2002;33:2334–2335. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000027211.73567.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik AB. Mechanisms of neurogenic pulmonary edema. Circ Res. 1985;57:1–18. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedý J, Zicha J, Kunes J, et al. Mechanisms of neurogenic pulmonary edema development. Physiol Res. 2008;57:499–506. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mascia L. A cute lung injury in patients with severe brain injury A double hit model. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gajic O, Manno EM. Neurogenic pulmonary edema Another multiplehit model of acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1979–1980. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000277254.12230.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naidech AM, Bassin SL, Garg RK, et al. Cardiac troponin I and acute lung injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11:177–182. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn JM, Caldwell EC, Deem S, et al. Acute lung injury in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage Incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:196–202. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000194540.44020.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitamura Y, Nomura M, Shima H, et al. Acute lung injury associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome following subarachnoid hemorrhage A survey by the Shonan Neurosurgical Association. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010;50:456–460. doi: 10.2176/nmc.50.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naidech AM, Bendok BR, Tamul P, et al. Medical complications drive length of stay after brainhemorrhage A cohort study. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10:11–19. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland MC, Mackersie RC, Morabito D, et al. The development of acute lung injury is associated with worse neurologic outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2003;55:106–111. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000071620.27375.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, et al. Incidence,case fatality functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time,according to age,sex,ethnic originA systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:167–176. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein JN, Fazen LE, Snider R, et al. Contrast extravasation on CT angiography predicts hematoma expansion in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2007;68:889–894. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257087.22852.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data via the EM Algorithm. J R Stat Soc. 1977:1–38. (Ser B. 39) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, APACHE II, et al. A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemphill JC3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, et al. The ICHscore A simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891–897. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meredith W, Rutledge R, Fakhry SM, et al. The conundrum of the Glasgow Coma Scale in intubated patients A linear regression prediction of the Glasgow verbal score from the Glasgow eye and motor scores. J Trauma. 1998;44:839–844. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199805000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flibotte JJ, Hagan N, O’Donnell J, et al. Warfarin, hematoma expansion, and outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2004;63:1059–1064. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000138428.40673.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK, et al. U.S. Critical Illness Injury Trials Group: Lung Injury Prevention Study Investigators (USCIITG-LIPS): Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury Evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:462–470. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0549OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Neal HR, Jr, Koyama T, Koehler EA, et al. Prehospital statin and aspirin use and the prevalence of severe sepsis and acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1343–1350. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182120992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erlich JM, Talmor DS, Cartin-Ceba R, et al. Prehospitalization antiplatelet therapy is associated with a reduced incidence of acute lung injury A population-based cohort study. Chest. 2011;139:289–295. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. Report of the American-European consensus conference onARDSdefinitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes and clinical trial coordination. The Consensus Committee. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20:225–232. doi: 10.1007/BF01704707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tung RH, Garcia C, Morss AM, et al. Utility of B-type natriuretic peptide for the evaluation of intensive care unit shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1643–1647. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000133694.28370.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoesch RE, Lin E, Young M, et al. Acute lung injury in critical neurological illness. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:587–593. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182329617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheu CC, Gong MN, Zhai R, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of sepsis-related vs non-sepsis-related ARDS. Chest. 2010;138:559–567. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gong MN, Bajwa EK, Thompson BT, et al. Body mass index is associated with the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Thorax. 2010;65:44–50. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.117572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong MN, Thompson BT, Williams P, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome Potential role of red cell transfusion. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165566.82925.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calfee CS, Matthay MA, Eisner MD, et al. Active and passive cigarette smoking and acute lung injury after severe blunt trauma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1660–1665. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1802OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fowler AA, Hamman RF, Good JT, et al. Adult respiratory distress syndrome Risk with common predispositions. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:593–597. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-5-593. (5 Pt 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yilmaz M, Keegan MT, Iscimen R, et al. Toward the prevention of acute lung injury: Protocol-guided limitation of large tidal volume ventilation and inappropriate transfusion. Crit Care Med 2007. 35:1660–1666. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269037.66955.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gajic O, Dara SI, Mendez JL, et al. Ventilator-associated lung injury in patients without acute lung injury at the onset of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1817–1824. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000133019.52531.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gajic O, Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A, et al. Ventilator settings as a risk factor for acute respiratory distress syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:922–926. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jia X, Malhotra A, Saeed M, et al. Risk factors for ARDS in patients receiving mechanical ventilation for > 48 h. Chest. 2008;133:853–861. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2006. 354:2564–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunst MA, Minei JP. Transfusion of blood products and nosocomial infection in surgical patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:428–432. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32826385ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hensler T, Heinemann B, Sauerland S, et al. Immunologic alterations associated with high blood transfusion volume after multiple injury Effects on plasmatic cytokine and cytokine receptor concentrations. Shock. 2003;20:497–502. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000095058.62263.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Looney MR, Gropper MA, Matthay MA. acute lung injury A review Transfusion-related acute lung injury A review. Chest. 2004;126:249–258. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Curtis BR, McFarland JG. Mechanisms of transfusion-of -related acute lung injury (TRALI) Anti-leukocyte antibodies. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(5):S118–S123. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000214293.72918.D8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silliman CC, Ambruso DR, Boshkov LK. Transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood. 2005;105:2266–2273. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan H, Belsher J, Yilmaz M, et al. Fresh-frozen plasma and platelet transfusions are associated with development of acute lung injury in critically ill medical patients. Chest. 2007;131:1308–1314. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han S, Martin GS, Maloney JP, et al. Short women with severe sepsis-related acute lung injury receive lung protective ventilation less frequently An observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15:R262. doi: 10.1186/cc10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamidi SA, Dickman KG, Berisha H, et al. 17β-estradiol protects the lung against acute injuryPossible mediation by vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4729–4737. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Speyer CL, Rancilio NJ, McClintock SD, et al. Regulatory effects of estrogen on acute lung inflammation in mice. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C881–C890. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00467.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis DP, Vadeboncoeur TF, Ochs M, et al. The association between feld Glasgow Coma Scale score and outcome in patients undergoing paramedic rapid sequence intubation. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duncan R, Thakore S. Decreased Glasgow Coma Scale score does not mandate endotracheal intubation in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferguson ND, Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A, et al. Clinical risk conditions for acute lung injury in the intensive care unit,hospital ward A prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R96. doi: 10.1186/cc6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Erickson SE, Martin GS, Davis JL, et al. NIH NHLBI ARDS Network: Recent trends in acute lung injury mortality 1996–2005. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1574–1579. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fefdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]