Epigenetics is driven by posttranslational modifications, such as methylation and acetylation of Arg and Lys residues. A less well publicized modification, namely conversion of Arg to citrulline (Cit), began to receive attention in the 1990s, when it was discovered that autoantibodies targeting citrulline-embedded epitopes are present in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.[1] The Arg-to-Cit conversion in histones has now been correlated with the regulation of gene expression.[2] PAD4, a member of the Protein Arginine Deiminase (PAD) enzyme family that catalyze this transformation, is overexpressed in rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, multiple sclerosis, and glaucoma.[3]Only a few assays have been described for the PAD enzyme family, including colorimetric[4], coupled[5], SDS-PAGE gel[6], affinity probe fluorescent polarization[7], and protein array[8] approaches. We describe herein a PAD4 activity fluorescence-based sensing strategy that can be employed throughout the visible spectrum and into the near infrared. The flexibility inherent within this strategy offers the ability to simultaneously monitor the activity of PAD4 along with other enzymes that modify histones.

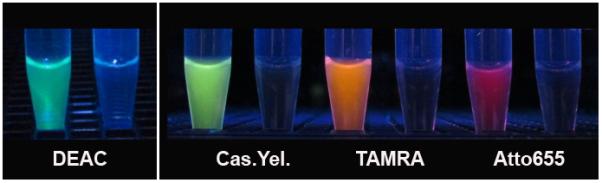

A particularly appealing biosensor design strategy employs fluorescently quenched substrates that experience relief from quenching upon conversion to product. For example, protease sensors have been designed that possess a fluorophore on one side of the scissile bond and a fluorescent quencher on the other.[9] Strategies developed for other enzymes employ fluorescent quencher molecules that are stripped away from the fluorophore-containing product.[10] It occurred to us that the PAD4-catalyzed conversion of a positively charged Arg residue (compound A) to a neutral Cit (compound C) should lead to the direct release of a noncovalently associated, negatively charged, quencher molecule (Q-) from a fluorescently quenched complex (compound B, Scheme 1). Furthermore, this strategy struck us as potentially applicable to a wide variety of fluorophores, thereby offering the flexibility to simultaneously visualize the action of PAD4 and other enzymes using wavelength-distinct sensors.[11]

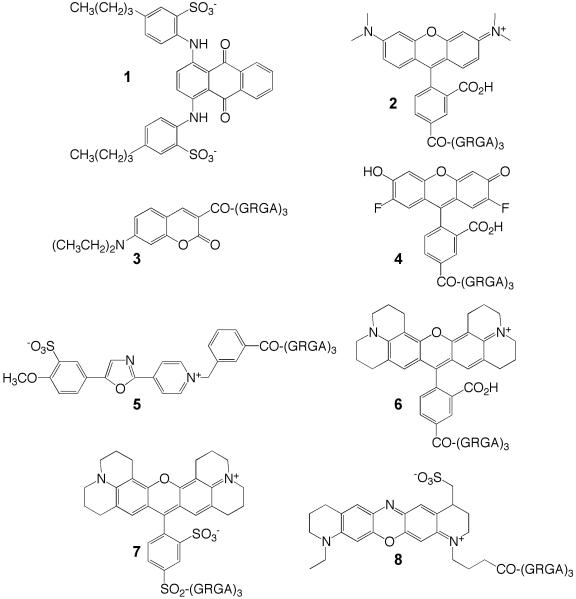

Scheme 1.

The fluorescent PAD4 substrate A forms a non-fluorescent noncovalent complex B with a negatively charged quencher dye molecule. Upon citrullination of the PAD4 substrate, the now neutral product C loses its affinity for the dye, and a fluorescent response is observed.

We prepared the following analogs of Ac-Ser-Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala, an efficient PAD4 substrate[12]: (a) a Gly-for-Ser substitution to preclude the possibility of phosphorylation when monitoring PAD4 activity in the presence of protein kinases (vide infra); (b) multimerized versions of (Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala)n to enhance the formation of the fluorescently quenched complex B (Scheme 1); (c) N-terminal attachment of the rhodamine derivative TAMRA and subsequently, upon identification of an optimized TAMRA-(Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala)nsubstrate, other fluorophores.

A library of 47 commercially available dyes was screened against TAMRA-Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala and TAMRA-(Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala)3(2) to identify fluorescent quenchers (Supporting Information). Although TAMRA-Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala, with only a single Arg residue, is recalcitrant to significant fluorescent quenching, the fluorescence of the corresponding trimer is dramatically quenched by a variety of dyes. Several of the latter were examined for their ability to quench the fluorescence of TAMRA-(Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala)3 and generate a fluorescent enhancement upon exposure to PAD4 (Supporting Information). Our lead, Acid Green 27 (1), in combination with the peptide trimer, displays an impressive PAD4-catalyzed 57 ± 2-fold increase in fluorescence. Furthermore, the tetramer, TAMRA-(Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala)4, exhibits a 166 ± 10-fold increase in fluorescence and an analog, (Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala)2-Lys(TAMRA)-(Gly-Arg-Gly-Ala)2, displays a 138 ± 7-fold enhancement in fluorescence upon citrullination.

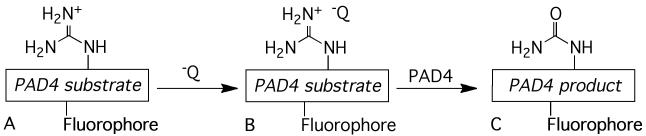

The presumed resistance of the Cit-containing products(s) to Acid Green 27-mediated fluorescence quenching was confirmed by preparing authentic samples containing one, two, and three Cit residues. The fluorescence of Cit-containing analogs of TAMRA-GlyXaaGlyAlaGlyXaaGlyAlaGlyXaaGlyAla as a function of Acid Green 27 concentration is shown in Figure 1, where Xaa = Arg or Cit. Fluorescence quenching by Acid Green 27 is most pronounced as follows: (GRGA)3 > mono-substituted Cit > di-substituted Cit > tri-substituted Cit, supporting our hypothesis that the conversion of positively charged Arg to neutral Cit residues disrupts dye binding (Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Fractional fluorescence of Cit-for-Arg TAMRA-(GRGA)3 derivatives as a function of Acid Green 27 concentration. Fractional fluorescence = fluorescence in the presence versus the absence of Acid Green 27. TAMRA-(GRGA)3= Arg••Arg••Arg (●); Arg••Arg••Cit (◇); Cit••Arg••Arg (○); Cit••Cit••Arg (□); Arg••Cit••Cit (△); Cit••Cit•Cit (▲).

Simultaneous visualization of the activity of multiple enzymes offers the possibility of concurrently monitoring the response of several biochemical pathways to environmental stimuli. However, the response of the sensor associated with each enzymatic activity must be wavelength distinct. This lead us to explore the range of fluorophores that respond to the Scheme 1 strategy, which offers an assessment of the flexibility of PAD4 assay to work in concert with reporters of other enzyme-catalyzed reactions. We prepared Fl-(GRGA)3 derivatives where Fl = DEAC (3; λem 480 nm), Oregon Green 488 (4; λem 525 nm), Cascade Yellow (5; λem 545 nm), Rox (6; λem 591 nm), Texas Red (7; λem 615 nm), and Atto 655 (8; λem 680 nm).

Each Fl-(GRGA)3 derivative was screened with the quencher library (Supporting Information). With the exception of Oregon Green 488, all substrates are strongly susceptible to quenching, most notably by Acid Green 27: DEAC (49 ± 1-fold @ 480 nm) Cascade Yellow (55 ± 2-fold @ 545 nm), Rox (133 ± 9-fold @ 610 nm), Texas Red (156 ± 10-fold @ 610 nm), and Atto 655 (48 ± 5-fold @ 680 nm).

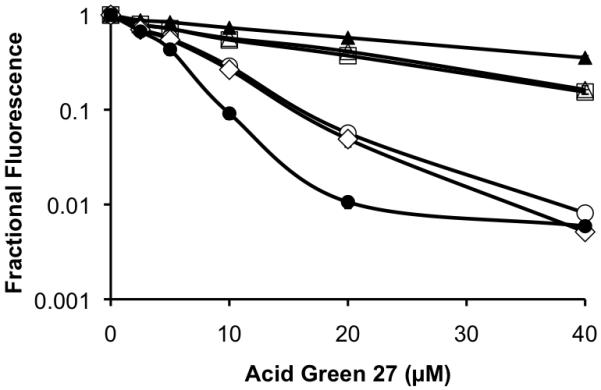

The large fluorescence changes associated with the PAD4 substrates are easily visualized without sophiscated instrumentation. The DEAC, Cascade Yellow, TAMRA and Atto 655 derivatives have very different emision wavelengths and good conversion rates, and thus were selected for side-by-side photoimaging studies. With the exception of DEAC-(GRGA)3, for which a Xe flash lamp and proper filters were employed to eliminate UV light interference with the camera, fluorophore excitation was performed with a hand-held UV lamp and emission was photographed with a Vis-IR camera (Figure 2). In an analogous fashion, we captured color images directly from the spectrofluorimeter by integrating the Vis-IR camera with the sample chamber (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Visualization of Fluorophore-(GRGA)3 PAD4 substrates. The DEAC-peptide was excited with a Xe Flash lamp and all others with a Hg arc lamp. Each sample set was incubated with (left) and without (right) PAD4 for 60 min prior to image capture.

The diversity of fluorophores compatible with PAD4 catalysis furnishes the flexibility to assemble paired fluorescent enzyme sensors that enable simultaneous monitoring of multiple enzymatic activities. For example, histones are known to suffer a wide variety of enzyme-catalyzed modifications which, in turn, influence gene expression. The cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) is the first enzyme shown to phosphorylate histones.[13] We paired the PAD4 TAMRA-(GRGA)3 sensor with a previously described PKA peptide-based sensor, Ac-GRTGRRDap(pyrene)SYP-amide, that reports phosphorylation via a pyrene fluorophore.[5, 6] The fluorescence changes of PAD4 and PKA substrates were monitored at 590 and 400 nm, respectively. An increase in PKA substrate fluorescence is only observed in the presence of PKA and, similarly, an increase in PAD4 substrate fluorescence is only observed in the presence of PAD4 (Figure 3). The activity of both enzymes can be simultaneously monitored and the observed activity under combined conditions for each enzyme is the same as that of the enzymes alone. Finally, we examined the ability of the molecular construct 3 to detect endogenous PAD4 activity in lysates from a human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60). Since PAD4 is only found in the nucleus (confirmed by Western blot analysis; Figure 4b), we compared PAD4 activities in nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts (Figure 4a). As expected, only the nuclear extract displays PAD4 activity. Furthermore, the observed deiminase activity is Ca2+-dependent and blocked by the PAD4 inhibitor minocycline, which is both consistent with and reflective of PAD4 action on sensor 3.

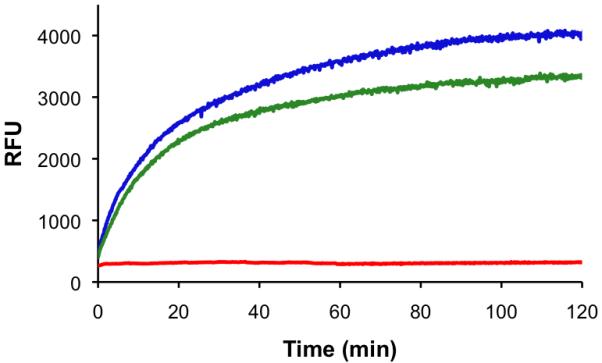

Figure 3.

Multicolor monitoring of PKA and PAD4 activity. a) Observed change in relative fluorescence units (λex 340 nm; λem 400 nm) of the PKA substrate in the presence of PAD4 (red), PKA (green), and both enzymes (blue). b) Observed change in relative fluorescence units (λex 550 nm; λem 590 nm) of the PAD4 substrate in the presence of PAD4 (red), PKA (green), and both enzymes (blue). PAD4, PKA, and their respective substrates were combined as a single mixture. Separation of results based on wavelength is provided for ease of presentation.

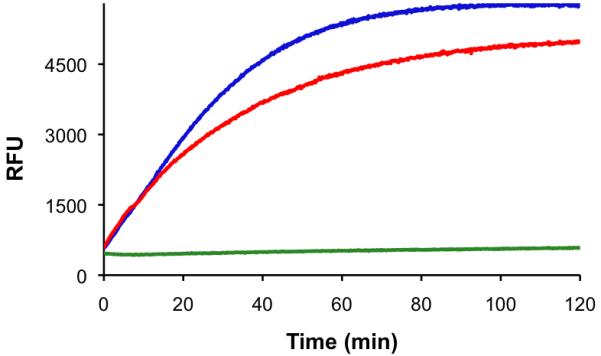

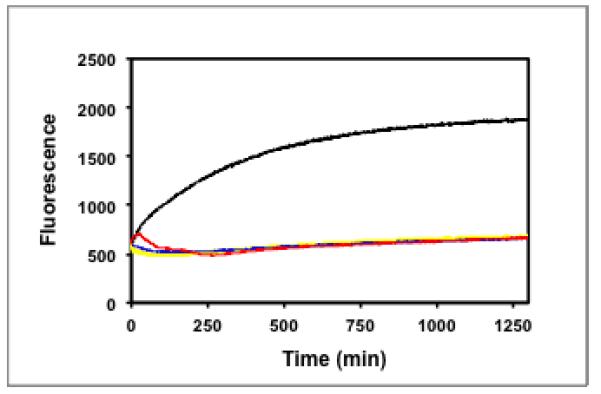

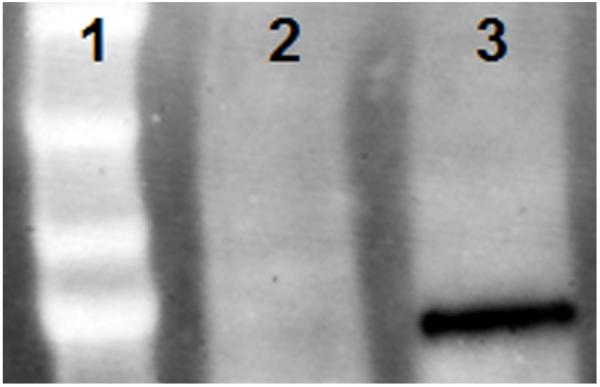

Figure 4.

(a) Fluorescence change of PAD4 substrate 3/quencher 2 pair upon exposure to HL-60 nuclear extract in the presence of Ca2+ (black); HL-60 cytoplasmic extract in the presence of Ca2+(yellow); HL-60 nuclear extract in the absence of Ca2+(green); HL-60 nuclear extract in the presence of Ca2+and 2 mM minocycline (red). (b) Molecular weight markers (lane 1); cytoplasmic (lane 2), and nuclear extract (lane 3) probed with PAD4 antibody.

In summary, we have created a series of PAD4 sensors that furnish a robust fluorescent response across the visible spectrum and into the near infrared. Given the demonstrated biological and biomedical significance of multiplexing nucleic acid and protein content from cells, sensors that are tunable to specific windows throughout the visible and near IR potentially enable the simultaneous monitoring of multiple enzymatic activities.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Structures of Acid Green 27 (1) and fluorophore-(GRGA)3 PAD4 substrates 2 – 8.

Table 1.

Fluorescence fold change (ΔFl) and initial rate (μmol/min-mg) of PAD4-catalyzed citrullination of TAMRA-substrates (λem 585nm)[a]

| Substrate | ΔFl | Initial Rate |

|---|---|---|

| TAMRA-GRGA | 1.5 ± 0.1 | N.D. |

| TAMRA-(GRGA)3 (2) | 57 ± 2 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| TAMRA-(GRGA)4 | 166 ± 10 | 0.021 ± 0.002 |

| Ac(GRGA)2K(TAMRA)(GRGA)2 | 138 ± 7 | 0.033 ± 0.005 |

20 μM Acid Green 27, 5 μM substrate peptide, 30 nM PAD4.

Footnotes

We thank the NIH (CA159189) for financial support.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- [1].Schellekens GA, de Jong BA, van den Hoogen FH, van de Putte LB, van Venrooij WJ. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:273–281. doi: 10.1172/JCI1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Klose RJ, Zhang Y. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrm2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Thompson PR, Fast W. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:433–441. doi: 10.1021/cb6002306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jones JE, Causey CP, Knuckley B, Slack-Noyes JL, Thompson PR. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:616–627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Knipp M, Vasak M. Anal Biochem. 2000;286:257–264. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liao YF, Hsieh HC, Liu GY, Hung HC. Anal Biochem. 2005;347:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Knuckley B, Luo Y, Thompson PR. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Knuckley B, Jones JE, Bachovchin DA, Slack J, Causey CP, Brown SJ, Rosen H, Cravatt BF, Thompson PR. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46:7175–7177. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02634d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Guo Q, Bedford MT, Fast W. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:2286–2295. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05089c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Funovics M, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;377:956–963. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Knight CG. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:18–34. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Agnes RS, Jernigan F, Shell JR, Sharma V, Lawrence DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6075–6080. doi: 10.1021/ja909652q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sharma V, Agnes RS, Lawrence DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2742–2743. doi: 10.1021/ja068280r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mayer-Almes F-J. Vol. DE 10239005. Germany: 2004. [Google Scholar]; Rhee HW, Lee SH, Shin IS, Choi SJ, Park HH, Han K, Park TH, Hong JI. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:4919–4923. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wakata A, Lee HM, Rommel P, Toutchkine A, Schmidt M, Lawrence DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1578–1582. doi: 10.1021/ja907226n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang Q, Zimmerman EI, Toutchkine A, Martin TD, Graves LM, Lawrence DS. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:887–895. doi: 10.1021/cb100099h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Knuckley B, Causey CP, Jones JE, Bhatia M, Dreyton CJ, Osborne TC, Takahara H, Thompson PR. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4852–4863. doi: 10.1021/bi100363t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Reimann EM, Walsh DA, Krebs EG. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1971;246:1986–1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.