Abstract

Purpose: Abnormal growth of vertebral body growth plate (VBGP) is considered as one of the etiologic factors in the adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). It was well-known that melatonin was correlated with the emergence and development of AIS. This study aimed to investigate the effect of melatonin on rat VBGP chondrocytes in vitro.

Methods:Chondrocytes were isolated from rat VBGP, and treated with or without melatonin. Cell proliferation was measured by the Alamar Blue assay. Gene expression of collagen type II and aggrecan were evaluated by real-time PCR. Expression of the melatonin receptors (MT1, MT2), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, a cell proliferation marker), Sox9 (a chondrocytic differentiation marker) and Smad4 (a common mediator in regulating the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes) were detected by Western blotting.

Results: Expression of melatonin receptors (MT1, MT2) were detected in the rat VBGP chondrocytes. Melatonin, at 10 and 100 µg/mL concentration, significantly inhibited the proliferation of VBGP-chondrocytes and the gene expression of collagen type II and aggrecan, and down-regulated the protein expression of PCNA, Sox9 and Smad4. In addition, the inhibitory effect of melatonin was reversed by luzindole, a melatonin receptor antagonist.

Conclusions: These results suggest that melatonin at high concentrations can inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of VBGP chondrocytes, which might give some new insight into the pathogenic mechanism of AIS.

Keywords: melatonin, vertebral body growth plate, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, Sox9, Smad4.

Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a three-dimensional structural deformity of the spine which is more commonly seen in girls 1-3. The longitudinal growth of the human vertebral body is through the growth and development of the growth plate 4. The proliferation and differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes during the growth period plays a key role in regulation of the development of vertebral growth plate 5. Growing evidence suggested that the growth kinetics indexes of vertebral body growth plate (VBGP) were higher in AIS patients 6-9. However, the mechanism of regulating the proliferation and differentiation of VBGP chondrocytes in the AIS patients is largely unknown.

Melatonin, or N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamin, is a hormone mainly synthesized and secreted by the pineal gland 10. Melatonin exhibits potential multifunctional bioactivities, such as antioxidative defense, anti-inflammatory, endocrinologic and behavioral effects 10-12. Melatonin deficiency experimentally induced the development of scoliosis in the pinealectomised chicken model 13-15. The serum level of melatonin in the patients who had progressive curve was significantly lower than the level in the patients who had a stable curve or in the control subjects 16. Dysfunction of melatonin signaling pathway occurs in osteoblasts derived from AIS patients 17, 18. These previous studies support the hypothesis that melatonin deficiency might be correlated with the pathogenesis of AIS. Melatonin was found to play an important role in modulating osteoblastic differentiation and bone formation 19-21. Recently, melatonin has also been reported to enhance cartilage matrix synthesis of porcine articular chondrocytes 22. However, the effect of melatonin on the proliferation and differentiation of VBGP chondrocytes remains unclear.

The present study was designed to investigate whether melatonin regulates the proliferation and differentiation of VBGP chondrocytes. Chondrocytes from rat VBGP were isolated and cultures in vitro, and treated with melatonin. Cell proliferation was analyzed. Gene expression of collagen type II and aggrecan, and protein expression of the melatonin receptors, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, which reflecting the proliferation potentiality of cells), Sox9 (a core transcription factor in controlling chondrocytic differentiation) and Smad4 (a common mediator in regulating the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes) were also measured.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of rat VBGP-chondrocytes

VBGP chondrocytes were isolated and cultured in vitro with improved trypsin-collagenase type II digestion method 23. Briefly, the spine samples were obtained from four 1-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats and the VBGP cartilage tissue was carefully separated under a microscope. After washed by sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the intact VBGP samples were digested in 0.25% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 minutes and then in 0.2% collagenase type Ⅱ (Sigma) for 1 hour. After that, the attached connective tissue and muscle were removed. The VBGP samples were then minced into small pieces and digested in 0.2% collagenase type Ⅱ for 5 hours. After removing tissue debris by a cribble, chondrocytes were collected in DMEM (Gibco BRL, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and incubated in humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 ℃. The medium was replaced every other day and the cells were subcultured by trypsinization with 0.25% trypsin when reaching a subconfluent state. The chondrocytes were identified by inverted phase contrast microscope. Chondrocytes were identified by inverted phase contrast microscope and staining with toluidine blue as previously described 24. The first to third passage cells were used in the following studies 25.

Melatonin treatment

Melatonin (Sigma) was dissolved in absolute ethanol (vehicle) according to the manufacturer's instructions. VBGP chondrocytes were seeded into 96-well culture plates at the rate of 1000 cells/well and were cultured with DMEM containing 10% FBS for 5 days. The medium was then replaced with serum-free DMEM containing various concentrations of melatonin (0.1, 1, 10 and 100 µg/mL), and the cells were incubated for 24 hours.

In order to further investigate the effect of melatonin on proliferation and differentiation of VBGP chondrocytes, luzindole (Sigma), a melatonin receptors antagonist, was also used in this study. Cells were pretreated for 60 minutes with luzindole at a concentration of 100 µg/mL before the melatonin treatment as previously described 26, 27.

Cell proliferation assay

The effect of melatonin on proliferation of VBGP chondrocytes was determined by Alamar Blue assay as previously described 28, 29. Briefly, after cells were cultured with melatonin-containing medium for 24 hours, Alamar Blue (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA, USA) was added directly to the medium at 10% of the medium volume and was incubated in the incubator for 5 hours. Fluorescence intensity (excitation wavelength: 530 nm, emission wavelength: 590 nm) was measured using a SpectraMax M5 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices Co., Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Total RNA isolation, real-time PCR

Gene expressions of collagen type II and aggrecan were examined by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR). Briefly, total RNA was extracted using the TRI Reagent ® according to the manufacturer's instructions. 0.5 μg of each RNA sample was converted to cDNA using PrimeScript® RT reagent Kit With gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China). Real-time PCR was performed using the Mx3005P device (Stratagene, CA, USA.) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequences of the sense and antisense primers were 5′- AAG GAT GGC TGC ACG AAA CA-3´ and 5′- TGT CCA TGG GTG CAA TGT CA-3´ for detecting rat collagen type II mRNA, 5′- GAG TCA ACC GCT GCA GAC AT -3´ and 5′- CAC ATT GCT CCT GGT CGA TCT-3´ for detecting rat aggrecan mRNA. Rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was amplified as an endogenous control with the primer pair of sense 5′-AGA CAG CCG CAT CTT CTT GT-3′ and antisense 5′-CCA CAG TCT TCT GAG TGG CA-3′. Relative gene expressions of collagen type II and aggrecan were calculated by the 2-∆∆CT method and normalized against the expression of GAPDH.

Western blot analysis

VBGP chondrocytes treated with melatonin at different concentrations were washed 3 times with cold PBS, then lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Bio., Haimen, China). The protein-containing supernatants were obtained by centrifuged at 4°C, 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes. The protein contents were measured according to Bradford's method 30. Equal amounts of proteins (40μg) were loaded per lane onto 10% SDS-PAGE gels for β-actin (43 kDa), PCNA (36 kDa), Sox9 (56 kDa), Smad4 (65 kDa), MT1/ MT2 (60/39 kDa), and transferred subsequently onto PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk in TBST, the membranes were probed with mouse anti-β-actin (1:1000; Zhongshan Goldenbridge Biotechnology Co., Beijing, China), mouse anti-PCNA (1:800; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit anti-Sox9 (1:100; Abcam, Temecula, CA, USA), rabbit anti-Smad4 (1:1000; Abcam) and rabbit anti-MEL-1A/B-R (namely MT1/2, 1:200; Santa Cruz) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed 3 times with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000; Santa Cruz) at room temperature for 1 hour. The immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescent kit (Pierce, Rockford,IL, USA).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The data from different groups were evaluated using one-way ANOVA, following by Dunnett's post hoc analysis. Multiple comparisons were performed using the LSD method or Dunnett's T3 method. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 software.

Results

Characterization of VBGP chondrocytes in vitro

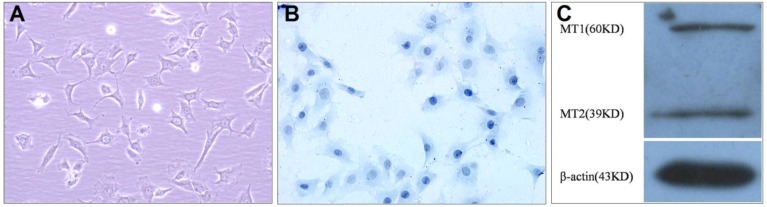

The cultured VBGP chondrocytes were mainly polygonal in shape, and few in irregular shape, their nuclei were mainly round or oval in shape (Fig.1A). Toluidine blue staining also showed that the cells varied somewhat in shape, the nuclei were stained intensely, and the cytoplasm were stained faintly and contained some fine granules (Fig.1B). In order to investigate whether VBGP chondrocyte is a target cell of melatonin, we measured the protein of melatonin receptors in primary cultured rat VBGP chondrocytes. As shown in Fig.1C, melatonin receptors (MT1, MT2) were detected in VBGP chondrocytes.

Fig 1.

Characterization of the cultured VBGP chondrocytes. The cell morphology was evaluated by inverted phase contrast microscope (A) and Toluidine blue staining (B). The cultured VBGP chondrocytes exhibited the mainly polygonal morphology with round or oval nuclei. Melatonin receptors (MT1, MT2) were detected in VBGP chondrocytes(C).

Effect of melatonin on VBGP chondrocyte proliferation

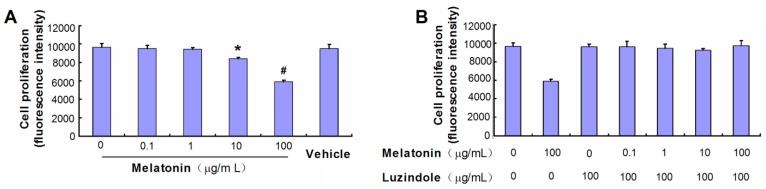

Melatonin significantly inhibited the proliferation of primary cultured rat VBGP chondrocytes by 13.07% at 10 µg/mL (P< 0.05) and by 38.76% at 100 µg/mL (P< 0.01), but not at 0, 0.1 and 1µg/mL (P> 0.05). There was no significant effect of vehicle (alcohol) on the proliferation of the cells (Fig.2A). Luzindole, a melatonin receptors antagonist, reversed the proliferation inhibition effect of melatonin on rat VBGP chondrocytes (Fig.2B). Furthermore, Melatonin treatment at 10 and 100 µg/mL concentrations also inhibited the protein expression of PCNA, which reflects the proliferation potentiality of cells (Fig.4).

Fig 2.

Effects of melatonin on the proliferation of the cultured VBGP chondrocytes. VBGP chondrocytes were incubated for 24 hours with medium containing melatonin at different concentration or vehicle (0.2% ethanol). Cell proliferation was evaluated using Alamar Blue assay. Date from three independent experiments are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 and #P < 0.01 vs the control (the 0 µg/ml melatonin group) (A). Cells were cultured for 24 hours in the presence or absence of melatonin combined with or without luzindole pretreatment at 100 µg/ml. The date showed that luzindole pretreatment could reverse the proliferation inhibition (B).

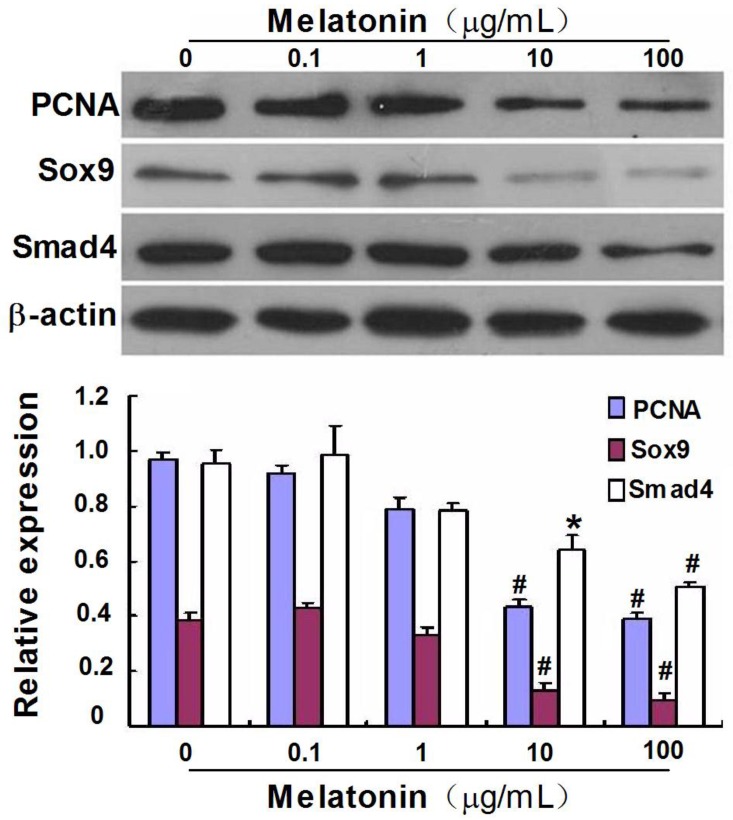

Fig 4.

Effect of melatonin on the protein expression of PCNA, Sox9 and Smad4 in cultured VBGP chondrocytes. VBGP-chondrocytes were treated with melatonin at different concentrations for 24 hours. The effect of melatonin on PCNA, Sox9 and Smad4 expression were assessed by western blotting. Picture and data are representative of three independent experiments. All values are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 and #P < 0.01 vs the control (the 0 µg/ml melatonin group).

Effect of melatonin on VBGP chondrocyte differentiation

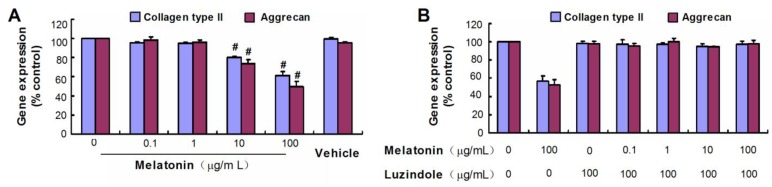

Collagen type II and aggrecan are two typical markers of chondrogenic differentiation. There was no obvious difference in mRNA levels of the chondrogenic marker genes between control groups and melatonin-treated groups at melatonin dosages of 0.1 and 1µg/mL(P> 0.05), but the high concentration of melatonin (10 µg/mL and 100 µg/mL) was shown to down-regulate gene expression of collagen type II and aggrecan of rat VBGP chondrocytes (Fig.3A). However, this inhibited effect was reversed with luzindole treatment at a concentration of 100 µg/mL (Fig.3B).

Fig 3.

Effects of melatonin on the gene expressions of collagen types II and aggrecan in cultured VBGP chondrocytes. VBGP chondrocytes were incubated for 24 hours with medium containing melatonin at different concentration or vehicle (0.2% ethanol). Gene expressions of collagen types II and aggrecan were evaluated by real-time PCR. Date from three independent experiments are presented as mean ± SD. #P < 0.01 vs the control (the 0 µg/ml melatonin group) (A). The melatonin at high concentrations inhibited the gene expressions of collagen types II and aggrecan, but this inhibited effect was reversed with luzindole pretreatment at 100 µg/ml(B).

To further gain insight into the effect of melatonin on the differentiation of VBGP chondrocytes, we investigated the effect of melatonin on expression of Sox9, a transcription factor regulating chondrocyte differentiation, and Smad4, which is a common mediator in regulating the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes. As shown in Fig.4, the protein expression of Sox9 and Smad4 were detected in VBGP chondrocytes, which were significantly down-regulated by melatonin treatment at the concentrations of 10 and 100 µg/mL.

Discussion

AIS is the single most common form of spinal deformity seen in orthopedic practice. Abnormal high growth indexes of the VBGP were well documented in AIS patients 6-9. Because scoliosis developed in pinealectomized chickens, melatonin deficiency has been implicated as a possible cause for scoliosis 13-17. In our study, the existence of melatonin receptors were demonstrated in the rat VBGP chondrocytes, which reveals that VBGP chondrocytes may be the target cells of melatonin. Therefore, there is an urgent need to understand the effects of melatonin on the proliferation and differentiation of VBGP chondrocytes.

The longitudinal growth of spine is through the growth and development of the spinal growth plate 4, 31. The longitudinal bone growth attributes to endochondral ossification, during which the cartilage transformed into bone 32. Endochondral ossification depends on the numbers of proliferative zone chondrocytes and their rate of proliferation, the volume of hypertrophic chondrocytes and the cartilage matrix turnover 33. Therefore, the chondrocytic proliferation events are very important in the development of vertebral growth plate. Here, we provided three lines of evidence for deciding the effects of melatonin on the proliferation of VBGP chondrocytes. First, the presence of melatonin significantly inhibited the proliferation of primary cultured rat VBGP chondrocytes at high concentrations (10 and 100 µg/ml), but not at low concentrations (0, 0.1 and 1µg/ml). Second, melatonin treatment at 10 and 100 µg/mL concentrations also inhibited the protein expression of PCNA, which is a cell proliferation marker 34. Third, melatonin inhibition of VBGP chondrocyte proliferation is attenuated by luzindole, a melatonin receptor antagonist. These findings suggested that melatonin at high concentrations can inhibit the proliferation of VBGP chondrocytes in vitro.

Chondrocyte differentiation is another key event in the process of endochondral bone formation 35. Collagen type II and aggrecan are the typical markers of chondrogenic differentiation. Sox9, an early chondrogenic transcription factor, is mainly required in regulating in successive steps of chondrocyte differentiation 36, 37. Smad4, a central intracellular mediator of transforming growth factor-beta signaling, was reported to play crucial roles in the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes 38-40. We found that melatonin at high concentration (10 and 100 µg/ml) suppressed the process of chondrogenic differentiation, as assessed by the decrease in the mRNA expression of collagen type II and aggrecan. Those melatonin-induced perturbations in chondrogenic gene expression can be prevented by luzindole treatment at a concentration of 100 µg/mL. Furthermore, high concentration of melatonin decreases the protein expression of Sox9 ans Smad4 in VBGP chondrocytes. The results hint that melatonin at high concentration may suppress the process of VBGP chondrocyte differentiation in vitro.

Melatonin deficiency secondary to pinealectomy experimentally induced scoliosis in bipedal animal models, which has similar anatomical features to those of human idiopathic scoliosis 13-17, 41. However, the published clinical data has addressed the controversy over the role of melatonin deficiency in AIS 16, 42-45. Serum melatonin concentrations vary considerably according to age: infants younger than 3 months of age secrete very little melatonin, the secretion of melatonin peaks from age 1 to 3 (325 pg/mL) and then declines gradually with age (10 to 60 pg/ mL for adults) 46. Relative anterior spinal overgrowth in AIS is believed to be a contributing cause of the lordosis and the hypokyphosis 5. Our results cannot clearly elucidate whether melatonin deficiency is involved into the anterior spinal overgrowth. Uncertainties still surround the role of melatonin at lower concentration on VBGP chondrocytes and future research is needed.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates for the first time that that melatonin at high doses can inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of VBGP chondrocytes in vitro. These findings give some new insight into the pathogenic mechanism of the AIS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81000785), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. S2012040006830).

References

- 1.Escalada F, Marco E, Duarte E. et al. Growth and curve stabilization in girls with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2005;30:411–7. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000153397.81853.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charles YP, Daures JP, de Rosa V. et al. Progression risk of idiopathic juvenile scoliosis during pubertal growth. Spine. 2006;31:1933–42. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000229230.68870.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JC. et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Lancet. 2008;371:1527–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bick EM, Copel JW. Longitudinal growth of the human vertebra; a contribution to human osteogeny. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:803–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballock RT, O'Keefe RJ. The biology of the growth plate. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:715–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siu King Cheung C, Tak Keung Lee W, Kit Tse Y. et al. Abnormal peri-pubertal anthropometric measurements and growth pattern in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a study of 598 patients. Spine. 2003;28:2152–7. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000084265.15201.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo X, Chau WW, Chan YL. et al. Relative anterior spinal overgrowth in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Results of disproportionate endochondral-membranous bone growth. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:1026–31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b7.14046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu F, Qiu Y, Yeung HY. et al. Histomorphometric study of the spinal growth plates in idiopathic scoliosis and congenital scoliosis. Pediatr Int. 2006;48:591–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2006.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day G, Frawley K, Phillips G. et al. The vertebral body growth plate in scoliosis: a primary disturbance of growth? Scoliosis. 2008;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan DX, Manchester LC, Hardeland R. et al. Melatonin: a hormone, a tissue factor, an autocoid, a paracoid, and an antioxidant vitamin. J Pineal Res. 2003;34:75–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swarnakar S, Paul S, Singh LP. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in health and disease: regulation by melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2011;50:8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Paredes SD. et al. Beneficial effects of melatonin in cardiovascular disease. Ann Med. 2010;42:276–85. doi: 10.3109/07853890903485748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagnall K, Raso J, Moreau M. et al. The development of scoliosis following pinealectomy in young chickens is not the result of an artifact of the surgical procedure. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2002;88:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Kelly C, Wang X, Raso J. et al. The production of scoliosis after pinealectomy in young chickens, rats, and hamsters. Spine. 1999;24:35–43. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199901010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machida M, Dubousset J, Imamura Y. et al. Role of melatonin deficiency in the development of scoliosis in pinealectomised chickens. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:134–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machida M, Dubousset J, Imamura Y. et al. Melatonin. A possible role in pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 1996;21:1147–52. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199605150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreau A, Wang DS, Forget S. et al. Melatonin signaling dysfunction in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2004;29:1772–81. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000134567.52303.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azeddine B, Letellier K, Wang da S. et al. Molecular determinants of melatonin signaling dysfunction in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:45–52. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31811f39fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park KH, Kang JW, Lee EM. et al. Melatonin promotes osteoblastic differentiation through the BMP/ERK/Wnt signaling pathways. J. Pineal Res. 2011;51:187–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sethi S, Radio NM, Kotlarczyk MP. et al. Determination of the minimal melatonin exposure required to induce osteoblast differentiation from human mesenchymal stem cells and these effects on downstream signaling pathways. J. Pineal Res. 2010;49:222–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth JA, Kim BG, Lin WL. et al. Melatonin promotes osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22041–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pei M, He F, Wei L. et al. Melatonin enhances cartilage matrix synthesis by porcine articular chondrocytes. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:181–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gartland A, Mechler J, Mason-Savas A. et al. In vitro chondrocyte differentiation using costochondral chondrocytes as a source of primary rat chondrocyte cultures: an improved isolation and cryopreservation method. Bone. 2005;37:530–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manning WK, Bonner WM Jr. Isolation and culture of chondrocytes from human adult articular cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 1967;10:235–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dharmavaram RM, Liu G, Mowers SD. et al. Detection and characterization of Sp1 binding activity in human chondrocytes and its alterations during chondrocyte dedifferentiation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26918–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olmez E, Kurcer Z. Melatonin attenuates alpha-adrenergic-induced contractions by increasing the release of vasoactive intestinal peptide in isolated rat penile bulb. Urol Res. 2003;31:276–9. doi: 10.1007/s00240-003-0327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nah SS, Won HJ, Park HJ. et al. Melatonin inhibits human fibroblast-like synoviocyte proliferation via extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase/P21(CIP1)/P27(KIP1) pathways. J Pineal Res. 2009;47:70–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakayama GR, Caton MC, Nova MP. et al. Assessment of the Alamar Blue assay for cellular growth and viability in vitro. J Immunol Methods. 1997;204:205–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Nasiry S, Geusens N, Hanssens M. et al. The use of Alamar Blue assay for quantitative analysis of viability, migration and invasion of choriocarcinoma cells. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1304–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickson RA, Deacon P. Spinal growth. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:690–2. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B5.3680325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breur GJ, VanEnkevort BA, Farnum CE. et al. Linear relationship between the volume of the hypertrophic chondrocytes and the rate of longitudinal bone growth in growth plates. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:348–59. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villemure I, Stokes IA. Growth plate mechanics and mechanobiology. A survey of present understanding. J Biomech. 2009;42:1793–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aizawa T, Kokubun S, Tanaka Y. Apoptosis and proliferation of growth plate chondrocytes in rabbits. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:483–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b3.7221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams SL, Cohen AJ, Lassová L. Integration of signaling pathways regulating chondrocyte differentiation during endochondral bone formation. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:635–41. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiyama H, Lyons JP, Mori-Akiyama Y. et al. Interactions between Sox9 and beta-catenin control chondrocyte differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1072–87. doi: 10.1101/gad.1171104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Martin JF. et al. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2813–28. doi: 10.1101/gad.1017802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakou T, Onishi T, Yamamoto T. et al. Localization of Smads, the TGF-beta family intracellular signaling components during endochondral ossification. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1145–52. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Tan X, Li W. et al. Smad4 is required for the normal organization of the cartilage growth plate. Dev Biol. 2005;284:311–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang SM, Hou ZH, Yang G. et al. Chondrocyte-specific Smad4 gene conditional knockout results in hearing loss and inner ear malformation in mice. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1897–1908. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machida M, Murai I, Miyashita Y. et al. Pathogenesis of idiopathic scoliosis. Experimental study in rats. Spine. 1999;24:1985–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199910010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilibrand AS, Blakemore LC, Loder RT. et al. The role of melatonin in the pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 1996;21:1140–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199605150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fagan AB, Kennaway DJ, Sutherland AD. Total 24-hour melatonin secretion in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. A case-control study. Spine. 1998;23:41–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brodner W, Krepler P, Nicolakis M. et al. Melatonin and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:399–403. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b3.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machida M, Dubousset J, Yamada T. et al. Serum melatonin levels in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis prediction and prevention for curve progression--a prospective study. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:344–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Girardo M, Bettini N, Dema E. et al. The role of melatonin in the pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl 1):S68–74. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1750-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]