Abstract

Past studies show that optimism and social support are associated with better adjustment following breast cancer treatment. Most studies have examined these relationships in predominantly non-Hispanic White samples. The present study included 77 African American women treated for nonmetastatic breast cancer. Women completed measures of optimism, social support, and adjustment within 10-months of surgical treatment. In contrast to past studies, social support did not mediate the relationship between optimism and adjustment in this sample. Instead, social support was a moderator of the optimism-adjustment relationship, as it buffered the negative impact of low optimism on psychological distress, well-being, and psychosocial functioning. Women with high levels of social support experienced better adjustment even when optimism was low. In contrast, among women with high levels of optimism, increasing social support did not provide an added benefit. These data suggest that perceived social support is an important resource for women with low optimism.

Keywords: social support, optimism, breast cancer, African American, psychological adjustment

Optimism is the tendency to believe that one will generally experience positive versus negative outcomes in life (Scheier & Carver, 1985). The literature suggests that optimism can promote better emotional adjustment and physical health (Peterson, 2000). Following cancer treatment, optimism is associated with better psychological adjustment (Carver et al., 2005; Friedman et al., 2006; Schou et al., 2005), greater feelings of physical attractiveness (Abend & Williamson, 2002), and greater satisfaction with life (Carver et al., 1994).

Perceived social support is also an important resource for individuals with cancer. Perceived support is the belief that support is available if needed (Procidano & Heller, 1983; Wethington & Kessler, 1986). Cross-sectional (Beder, 1995; Bloom et al., 2001; Parker et al., 2003) and prospective studies (Devine et al., 2003; Northouse, 1988) demonstrate a positive association between perceived social support and psychological adjustment following cancer treatment. Helgeson and colleagues (2004) examined patterns of adjustment to breast cancer over four years. Social support distinguished between different courses of mental functioning, as women who experienced declines in mental health also had few social resources.

Evidence indicates that optimism and social support are positively related (e.g., Boland & Cappeliez, 1997; Park & Folkman, 1997). Social support has been proposed as an important mediator of the optimism-adjustment relationship, as an optimistic disposition could attract more people, allow an individual to build more relationships, and increase social support in times of stress (Brissette et al., 2002; Dougall et al., 2001). An increasing number of studies support this hypothesis. Optimistic individuals demonstrate greater satisfaction with support following surgery (Scheier et al., 1989) and optimistic individuals report less loneliness and greater feelings of support in new social contexts (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1993). Following breast cancer surgery, optimistic women report higher levels of perceived support and greater feelings of attractiveness (Abend & Williamson, 2002). Several studies demonstrate that perceived social support mediates (partially or fully) the relationship between optimism and better psychological adjustment in survivors of traumatic events (Dougall et al., 2001; Sherman & Walls, 1995), among college students (Brissette et al., 2002; Mosher et al., 2006), and breast cancer survivors (Trunzo & Pinto, 2003). However, these studies have been conducted in predominantly non-Hispanic White samples. One study (Mosher et al., 2006) included Black college students, but these findings may not generalize to the larger population.

The factors that predict adjustment and the interrelationships among psychosocial variables may not be equivalent across racial or ethnic groups (Hunt et al., 2000; Lincoln et al., 2003). Even if breast cancer survivors report similar levels of adjustment, meaningful differences may exist across groups that prohibit generalization of findings from studies with non-Hispanic White women (Ashing-Giwa et al., 1999; Meyerowitz et al., 1998; Porter et al., 2006). Unique circumstances evident within different populations may confer risk (e.g., more advanced disease, less access to healthcare) or protection (e.g., cohesive social and community networks) against poor outcomes. For example, Lincoln and colleagues (2003) examined predictors of psychological distress in African Americans and White Americans. For African Americans, social support was not impacted by financial strain or trauma, but these events were associated with less support for White Americans. Social support also had a direct impact on distress for African Americans but not for Whites suggesting that social support made a greater contribution to adjustment for African Americans than White Americans.

Recent studies indicate that African American and White breast cancer patients have similar levels of social support (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2007; Friedman et al., 2006; Giedzinska et al., 2004), and both groups of women tend to seek social support to cope with their disease (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004; Bourjolly & Hirschman, 2001; Henderson et al., 2003). However, sources and types of social support vary across racial or ethnic groups. African American women are more likely to seek support from God (Bourjolly & Hirschman, 2001), use informal social support networks (Guidry et al., 1997), and view support from immediate and extended family members as salient (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). In a study of African American cancer survivors, Hamilton and Sandleowski (2004) found that participants reported using types of social support that are not emphasized in the current literature. Reports of social support focused on the presence of others, encouraging words that promote positive self-evaluation, distracting activities, offers of prayers, and assistance in maintaining social roles. The authors concluded that culture and financial resources need to be considered when conceptualizing social support.

Studies also suggest that optimistic expectancies may be influenced by culture, the socio-cultural context, and childhood or past experiences (Heinonen et al., 2006; Korkeila et al., 2004). In a population based study of 19,970 young adults, Korkeila et al. (2004) found that an increasing number of childhood adversities (e.g., financial difficulties, serious family conflict) was associated with decreasing levels of optimism. Mattis and colleagues (2003) examined the association between everyday racism, social support, religiosity, and optimism in African American men and women. Experiences of everyday racism emerged as the strongest predictor of lowered optimism. The authors concluded that everyday racism influences optimism by complicating explanatory styles. In the context of racism, hard work and talent may not result in positive outcomes, and the extent to which an individual is treated with respect and equality can depend on the beliefs of others (Mattis et al, 2003).

Social support may be particularly important for African American women with low optimism. Harrell (2000) described social support as an important resource African Americans use in coping with racism and stress. Data suggest that African Americans prefer seeking social support to cope with race-related stress (Utsey et al., 2000), and social support buffers or reduces the negative impact of race-related stress on quality of life (Utsey et al., 2006). Social support also has been shown to buffer the negative impact of acute economic stress on depressive symptoms among African American women, but not White women (Ennis et al., 2000).

The present study examined the relationships between optimism, social support, and adjustment in a sample of African American women with nonmetastatic breast cancer who were recruited for participation in a randomized clinical trial of a psychosocial support group intervention. The data in the current paper were collected during a baseline assessment that occurred prior to randomization. To reflect the conceptualization of social support used in the intervention, The Interpersonal Support Evaluations List – Short Form (ISEL-SF; Cohen & Hoberman, 1983) was used to assess social support. This measure assesses several types of social support including the availability of others, support that promotes positive self-evaluation, belonging support (i.e., the availability of others to do things with the patient), and tangible support. It was unclear whether optimism, social support, and adjustment would demonstrate relationships similar to those found in non-Hispanic White samples. Thus, we examined two hypotheses. First, we tested whether social support mediated the relationship between optimism and adjustment (i.e., psychological distress, psychological well-being, psychosocial functioning, and physical functioning). Second, we tested the hypothesis that social support buffered (i.e., reduces) the negative impact of lowered optimism on adjustment.

Method

Participants

Participants were accrued in Philadelphia, PA and Washington, D.C. and were identified via physician referral, medical record review, or self-referral. African American women with stage 0-IIIA breast cancer who had completed surgical treatment were eligible and recruited for a randomized clinical trial of a psychosocial intervention. For the clinical trial, the goal was to recruit women who had recently completed surgical treatment. In this sample, time since surgery ranged from 1 to 10 months (M=3.4 months post-surgery; SD=2.4): 47% of women were within two months of surgical treatment, 33% were within three to four months, 9% were within five to six months, 8% were within seven to eight months, and 3% were within nine to ten months. At the time of recruitment, 15% of women were still undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy and 8% were still undergoing radiation treatment. Exclusionary criteria were psychotic illness, drug or alcohol abuse, severe cognitive impairment, refusal of recommended treatment, or previous cancer diagnosis.

Of the 148 eligible women, 63% (N=93) agreed to participate, 33% (n=49) declined to participate (most often due to feeling burdened by the illness/treatment, work, or family commitments), and 4% (n=6) were unreachable by mail or phone. When compared on demographic and treatment variables, the only significant difference between participants and nonparticipants was age (nonparticipants were significantly older, p<.001). Participation rate did not differ by accrual site. Of the 93 participants, 14 women did not complete the social support measure because it was added after the first cohort had completed the questionnaire packet and two women did not complete the optimism measure. Thus, the final sample consisted of 77 African American women with stage 0-IIIA breast cancer.

Procedure

The data reported were drawn from a longitudinal study of a randomized support group intervention for African American women with breast cancer (Taylor et al., 2003). The data in the current paper were collected during the baseline assessment, which occurred prior to randomization and at the time of study accrual.

Institutional review board approval was obtained at all participating hospitals and all participants provided informed consent. Eligible patients were mailed an introductory letter describing the study or were referred to the study by their physician. All women were subsequently phoned to describe the study further and to determine their interest in participation. Upon enrollment, women completed a semi-structured interview and a series of standardized self-report questionnaires (see Measures section). Participants received financial compensation for participation and were reimbursed for transportation costs to attend the interview.

Measures

Demographic and medical information

Demographic information included age, education, household income, marital status, and employment status. Medical information was obtained via medical record review and included time elapsed since surgery, stage of disease, type of surgery, and type(s) of adjuvant therapy.

Life Orientation Test (LOT)

Optimism was measured using the LOT (Scheier & Carver, 1985). The LOT is composed of 8 items (with an additional 4 filler items) using a 5-point scale from 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Total scores range from 0 to 32 with higher scores reflecting higher optimism. Alpha reliability coefficients of .76 and higher have been reported (Carver et al., 1994; Scheier & Carver, 1985). In the current sample, alpha was .76 and three month test-retest reliability was r=.78. Maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis with oblique direct quartimin rotation (Jennrich & Sampson) was conducted. Consistent with prior studies (Marshall et al., 1992), a two-factor solution best fit the data (RMSEA = .04). Items reflecting optimism loaded on the first factor and items reflecting pessimism loaded on the second factor. These two factors were negatively correlated (r=−30).

Interpersonal Support Evaluations List – Short Form (ISEL-SF)

A short-form of the ISEL (Cohen & Hoberman, 1983) was used to assess social support. This measure includes 16 items that assess the following types of support: 1) appraisal support or the availability of someone to talk to about problems, 2) tangible support or the availability of material aid or instrumental support, 3) belonging support or the availability of people to do things with, and 4) self-esteem support or the availability of a positive comparison when comparing the self with others. Participants rate each item using a 4-point scale (1 = definitely true, 4 = probably false). For this study, we used the total support score with higher scores indicating greater perceived support (potential range = 16 to 64). For this sample, coefficient alpha was .78 and three month test-retest reliability was r=.71. Maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis with oblique direct quartimin rotation (Jennrich & Sampson) was conducted. While the ISEL-SF includes items representing four types of social support, a single factor solution best fit the data (RMSEA = .09) with item loadings ranging from .23 to .70. We have also examined the content validity of the ISEL-SF by comparing responses on this scale with women’s problems and concerns reported on questions using an open-ended response format (Shelby et al., 2006). The ISEL-SF adequately captured social support concerns women reported in an open-ended response format.

Mental Health Inventory (MHI)

To measure participants’ general psychological distress and well-being during the past month, we used the Medical Outcomes Study 17-item MHI (Stewart et al., 1992; Veit & Ware, 1983). The 17-item MHI includes two subscales: psychological distress (12 items; e.g., “Have you been low or very low in spirits?”) and psychological well-being (5 items; e.g., “Have you felt calm and peaceful?”). Participants respond using a 6-point scale from 1 (all of the time) to 6 (none of the time). Scores were transformed to a 100-point scale (Stewart et al., 1992) to aid in comparison across studies. Higher scores on the well-being scale indicate better psychological adjustment, while higher scores on the distress scale indicate greater levels of distress. In this sample, alpha was .84 for the well-being scale and .90 for the distress scale. Three month test-retest reliability was r=.68 for the well-being scale and r=.74 for the distress scale. Maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis with oblique direct quartimin rotation (Jennrich & Sampson) was conducted. A two-factor solution best fit the data (RMSEA = .09), with items that reflect well-being loading on one factor and items reflecting distress loading on a second factor. These two factors were negatively correlated (r=−57). We further examined the MHI by comparing responses on this scale with women’s problems and concerns reported using an open-ended response format (Shelby et al., 2006). The MHI adequately captured psychological concerns women reported in an open-ended response format.

Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System – Short Form (CARES-SF)

The CARES-SF (Schag et al., 1991) is a 59-item measure of cancer patients’ quality of life in which respondents indicate how much each item applied to them over the past month (0=not at all to 4=very much). The current study includes the 10-item Physical Functioning subscale (e.g., “I have difficulty bending or lifting”; “I frequently have pain”) and the 17-item Psychosocial subscale (e.g., “I worry about whether cancer is progressing”; “I have difficulty concentrating”). Items are averaged for each subscale (range = 0 to 4) and higher scores indicate poorer quality of life. In this sample, alpha was .88 for Physical Functioning and .80 for Psychosocial Functioning. Three month test-retest reliability was r=.65 for Physical Functioning and r=.74 for Psychosocial Functioning. Maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis using oblique direct quartimin rotation (Jennrich & Sampson) was conducted with items from these two subscales. A two-factor solution best fit the data (RMSEA = .09), with physical functioning items loading on one factor and psychosocial functioning items loading on a second factor. These two factors were positively correlated (r=.45). We further examined the CARES-SF subscales by comparing responses on these scales with women’s problems and concerns reported using an open-ended response format (Shelby et al., 2006). Both the Physical Functioning and Psychosocial Functioning scales captured women’s physical functioning concerns reported using an open-ended response format.

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations are provided. To be consistent with past studies (e.g., Brissette et al., 2002; Trunzo & Pinto, 2003), we conducted multiple linear regression analyses to test whether social support mediated the relationship between optimism and adjustment. Relationships were tested separately for psychological distress, well-being, psychosocial functioning, and physical functioning. A variable can be considered a mediator if the independent variable (optimism) is related to the mediator (social support), the independent variable and the mediator are related to the outcome (adjustment), and the relationship between the independent variable and the outcome is significantly reduced when the mediator is included (Barron & Kenny, 1986). Three linear regression analyses were conducted for each measure of adjustment to test for mediation: 1) optimism predicting adjustment, 2) optimism predicting social support, and 3) optimism and social support predicting adjustment. In each regression, demographic and medical variables found to be associated with adjustment (p< .10) were included as control variables. The Sobel test (1982) was used to test the significance of indirect effects. Because assumptions of the Sobel test are often violated in small samples, we also examined the significance of indirect effects using a bootstrap approach (with 5000 resamples) to obtain 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

Multiple linear regression analyses were also conducted to test whether social support buffered the impact of low optimism on adjustment. Separate regression models were conducted for each measure of adjustment. Each regression model included 1) demographic and medical control variables, 2) optimism, 3) social support, and 4) the optimism x social support interaction term. As recommended by Aiken and West (1991), variables were centered at the mean. For significant interaction terms, simple slopes analyses were conducted to facilitate interpretation of the interaction. To calculate the simple slopes and plot the interaction for interpretation, values one standard deviation above and below the mean of social support were used for high and low lines. Values one standard deviation above and below the mean of optimism were used to anchor the lines (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants were 77 African American women. Demographic and medical information are presented in Table 1. Bivariate analyses (ANOVA, Pearson and point-biserial correlations) were conducted to test for associations between demographic/medical variables and adjustment. Age and income were negatively associated with psychological distress (r=−24 to −27, p<.05) and psychosocial concerns (r=−23 to −27, p<.05). Being employed outside the home was associated with higher psychological well-being (r=.21, p=.07) and lower psychological distress, physical concerns, and psychosocial concerns (r=−26 to −31, p<.05). Receipt of chemotherapy was associated with greater psychological distress, physical concerns, and psychosocial concerns (r=.24 to .25, p<.05). There was no association between adjustment and education, partner status, stage of disease, type of surgery, time since surgery, radiation, or hormonal therapy (p>.10). In subsequent analyses testing for mediation and moderation, each regression controlled for the receipt of chemotherapy, age, income, and employment status.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | Mean | Standard deviation | % | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.5 | 12.8 | ||

| Partner status (% partnered) | 47 | 36 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Some high school | 14 | 11 | ||

| High school graduate | 35 | 27 | ||

| Some college | 25 | 19 | ||

| College graduate | 14 | 11 | ||

| Post-graduate work | 12 | 9 | ||

| Income | ||||

| <$12,000 | 16 | 12 | ||

| $12,000 to $24,0000 | 26 | 20 | ||

| >$24,000 to $36,000 | 35 | 27 | ||

| >$36,000 | 23 | 18 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed full or part-time | 43 | 33 | ||

| Retired | 34 | 26 | ||

| Unemployed | 10 | 7 | ||

| On leave due to illness | 13 | 10 | ||

| Months since surgery | 3.4 | 2.4 | ||

| Stage of disease | ||||

| 0 | 4 | 3 | ||

| I | 38 | 29 | ||

| II | 53 | 41 | ||

| IIIA | 5 | 4 | ||

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Lumpectomy/breast conserving surgery | 47 | 36 | ||

| Modified radical mastectomy | 53 | 41 | ||

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||

| Chemotherapy alone | 27 | 21 | ||

| Radiation therapy alone | 21 | 16 | ||

| Chemotherapy and radiation therapy | 29 | 22 | ||

| Hormonal treatment | 38 | 29 | ||

Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Analyses

Table 2 displays descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for optimism, social support, and adjustment. The average level of optimism (M=30.70, SD=4.61) was similar to levels reported in other studies of women with breast cancer (Friedman et al., 2006; Trunzo & Pinto, 2003) and studies of African American men and women (Mattis et al., 2003; Mosher et al., 2006). Women reported high levels of perceived social support, as the average was 55.75 (SD=6.47) on a scale that ranges from 16 to 64. This level of support is consistent with Hamilton and Sandelowski’s (2004) finding that 93% of African American breast cancer survivors reported having available social support. Finally, levels of psychological distress, well-being, psychosocial functioning, and physical functioning were similar to levels of adjustment reported in past studies of breast cancer survivors (Ashing-Giwa et al., 1999; Giedzinska et al., 2004). Similar to past studies, optimism and social support were positively related (r=.25, p<.05). Both optimism and social support were associated with lower distress, greater well-being, and fewer psychosocial concerns (p<.05; see Table 2). Optimism was negatively associated with physical functioning concerns (r=−24, p<.05).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for optimism, social support, and adjustment (N=77).

| Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Optimism (LOT) | 30.70 | 4.61 | 1.00 | |||||

| 2. Social support (ISEL-SF) | 55.75 | 6.47 | .25* | 1.00 | ||||

| 3. Psychological distress (MHI) | 18.18 | 12.78 | –42* | –34* | 1.00 | |||

| 4. Psychological well-being (MHI) | 56.91 | 15.69 | .49* | .39* | –66* | 1.00 | ||

| 5. Psychosocial functioning (CARES-SF) | 1.00 | 0.74 | –28* | –33* | .71* | –44* | 1.00 | |

| 6. Physical functioning (CARES-SF) | 1.02 | 0.74 | –24* | –14 | .48* | –35* | .66* | 1.00 |

p<.05

Mediation Analyses

In these analyses, we tested whether the relationship between optimism and adjustment was significantly reduced when accounting for the effect of social support. Each regression controlled for the receipt of chemotherapy, age, income, and employment status. Table 3 displays the final standardized βs for the mediation analyses.

Table 3.

Final standardized for paths testing mediation.a

| Psychological distress (MHI) | Psychological well-being (MHI) | Psychosocial functioning (CARES-SF) | Physical functioning (CARES-SF) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression model 1: | ||||

| Optimism → adjustment | –29** | .43** | –16 | –13 |

| Regression model 2: | ||||

| Optimism → social support | .24* | .24* | .24* | .24* |

| Regression model 3: | ||||

| Social support → adjustment | –27* | .31** | –25* | –06 |

| Optimism adjustment | –23* | .35** | –09 | –11 |

| Sobel test Z | –1.66 | 1.72 | Not tested | Not tested |

All regression models include receipt of chemotherapy, age, income, and employment status as control variables.

p < .05,

p < .01

Psychological distress

The first regression tested the relationship between optimism and distress. Optimism was negatively associated with psychological distress (β=−29, t(71)= −3.03, p=.003) accounting for 8% of the variance. The second regression examined the relationship between optimism and social support. Optimism was positively associated with social support (β=.24, t(71)= 2.08, p=.04) and accounted for 5% of the variance. The third regression model included both optimism and social support as predictors of distress. Social support was negatively associated with distress (β=−27, t(70)= −2.78, p=.007) and accounted for 6% of the variance. Finally, we examined whether the relationship between optimism and distress was significantly reduced after including social support in the regression model. Optimism continued to be significantly associated with distress (β=−23, t(70)= −2.41, p=.02, sr2=.05), with only a modest reduction in this relationship (see Table 3). The Sobel test (1982) revealed that social support was not a significant mediator of the optimism-distress relationship (Z=−1.66, p=.10). Bootstrapping analysis confirmed these findings (95% CI = −67, .00).

Psychological well-being

Optimism was positively associated with well-being (β=.43, t(71)= 4.11, p<.001, sr2=.17) and optimism was positively associated with social support (p<.05; see Table 3). After accounting for the contribution of optimism, social support was positively associated with well-being (β=.31, t(70)= 3.28, p=.003, sr2=.08). When including social support in the regression model, optimism continued to be significantly associated with well-being (β=.35, t(70)= 3.48, p=.001, sr2=.11), and the Sobel test (1982) indicated that social support was not a significant mediator of the optimism-well-being relationship (Z=1.72, p=.09). Bootstrapping analysis confirmed these results (95% CI = .00, .70).

Psychosocial and physical functioning

Optimism was no longer associated with psychosocial functioning after controlling for medical and demographic variables (β=−16, t(71)= −1.57, p=.12), and social support was not associated with physical functioning (see Table 3). Thus, tests for mediation were not conducted for psychosocial and physical functioning.

Moderator Analyses

These analyses tested whether social support buffered the impact of low optimism on adjustment. Each regression controlled for the receipt of chemotherapy, age, income, and employment status. Table 4 displays the multiple linear regression results. Unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors are provided, as standardized beta coefficients cannot be interpreted when an interaction term is included in the regression model (Aiken & West, 1991). The interaction between optimism and social support was significant for psychological distress (Β=.10, SE=.04, p=.02), psychological well-being (B=−11, SE=.05, p=.04), and psychosocial functioning (B=.01, SE=.003, p=.05) indicating that social support moderated the relationship between optimism and these variables. The interaction term accounted for an additional 4% of the variance in distress, well-being, and psychosocial functioning (see Table 4). The optimism by social support interaction was not significant for physical functioning (p=.30).

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression analysis testing whether social support buffers the impact of low optimism on adjustment (N=77).

| Variables | B | SE B | Semipartial r2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress (MHI) | |||

| Chemotherapya | 4.68 | 2.62 | .02 |

| Age | –0.37** | 0.11 | .09 |

| Income | –0.71 | 0.63 | .01 |

| Employment statusb | –9.03** | 2.61 | .09 |

| Optimism (LOT) | –0.66* | 0.26 | .05 |

| Social support (ISEL-SF) | –0.58** | 0.18 | .07 |

| Optimism x social support | 0.10* | 0.04 | .04 |

| Psychological well-being (MHI) | |||

| Chemotherapy | –4.75 | 3.43 | .02 |

| Age | 0.23 | 0.14 | .02 |

| Income | –0.49 | 0.82 | .003 |

| Employment status | 7.19* | 3.42 | .04 |

| Optimism (LOT) | 1.22** | 0.34 | .11 |

| Social support (ISEL-SF) | 0.81** | 0.24 | .09 |

| Optimism x social support | –0.11* | 0.05 | .04 |

| Psychosocial functioning (CARES-SF) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 0.32 | 0.17 | .03 |

| Age | –0.02 | 0.01 | .05 |

| Income | –0.05 | 0.04 | .01 |

| Employment status | –0.57** | 0.17 | .11 |

| Optimism (LOT) | –0.02 | 0.02 | .01 |

| Social support (ISEL-SF) | –0.03* | 0.01 | .05 |

| Optimism x social support | 0.01* | 0.003 | .04 |

| Physical functioning (CARES-SF) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 0.39* | 0.19 | .05 |

| Age | –0.02 | 0.01 | .04 |

| Income | –0.02 | 0.05 | .001 |

| Employment status | –0.68** | 0.19 | .14 |

| Optimism (LOT) | –0.02 | 0.02 | .01 |

| Social support (ISEL-SF) | –0.01 | 0.01 | .003 |

| Optimism x social support | 0.003 | 0.003 | .01 |

Chemotherapy: 0=no, 1=yes

Employment status: 0=not employed outside of home, 1=employed full or part-time

p < .05.

p < .01.

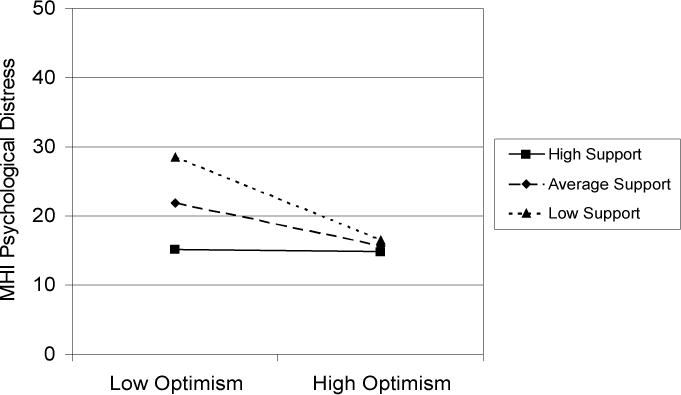

To interpret significant interaction terms, we calculated simple slopes and plotted the interactions. Across outcomes, social support buffered the impact of low optimism on adjustment. Figure 1 displays the impact of optimism and social support on psychological distress. Among women with low levels of optimism, increasing social support was associated with decreasing levels of distress. Social support was not associated with adjustment among women with high levels of optimism. A similar pattern of results was found for psychological well-being and psychosocial functioning. Higher levels of social support were associated with greater well-being among women with low levels of optimism, but there was no association between social support and well-being among women with high optimism. For psychosocial concerns, higher social support was associated with fewer concerns among women with high optimism, but social support did not impact psychosocial functioning among women with high levels of optimism. These findings suggest that social support is an important resource for women with low optimism. Results also suggest that high levels of social support do not provide an added benefit for women with high levels of optimism.

Figure 1.

Impact of perceived social support and optimism on psychological distress.

Discussion

Optimism and perceived social support have been identified as important resources for women with breast cancer (e.g., Bloom et al., 2001; Carver et al., 2005; Parker et al., 2003; Schou et al., 2005). However, most studies have been conducted in predominantly non-Hispanic White samples. The current study provides important and novel information about the relationships between optimism, social support, and adjustment in a sample of African American women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. While these women reported levels of optimism, social support, and adjustment similar to other samples (e.g., Ashing-Giwa et al., 1999; Giedzinska et al., 2004; Trunzo & Pinto, 2003), the interrelationships among these variables differed from those found in past studies. In contrast to previous findings (Brissette et al., 2002; Dougall et al., 2001; Mosher et al., 2006; Sherman & Walls, 1995; Trunzo & Pinto, 2003), social support did not mediate the relationship between optimism and adjustment. Instead, social support buffered the relationship between low optimism and increased psychological distress, reduced well-being, and poorer psychosocial functioning. While these data are correlational, our findings suggest that social support might be an important resource for women with low optimism.

The social and cultural factors that impact the lives of African American women may have an important influence on the relationships between optimism, social support, and adjustment. Recent studies suggest that there is a crucial link between culture, sociocultural context, and optimistic expectancies (Chang, 2001). While experiences of adversity in childhood (e.g., financial difficulties, exposure to serious conflicts) and racism have been shown to negatively impact optimism (Ek et al., 2004; Korkeila et al., 2004; Mattis et al., 2003), social support among African Americans does not appear to be negatively impacted by these experiences (Lincoln et al., 2003; Mattis et al., 2003). In contrast, studies conducted in African American samples show that social support serves as an important resource for coping with stressors, including experiences of racism (Harrell, 2000; Utsey et al., 2000), and social support buffers or reduces the negative impact of these stressors on quality of life (Ennis et al., 2000; Utsey et al., 2006). For African American women, the impact of optimism on adjustment may be mediated by other variables. Recent data suggest that feelings of personal control may mediate the relationship between extroversion and psychological distress in African Americans, but not in White Americans (Lincoln et al., 2003). Religious coping (prayer, church involvement, a positive relationship with God) could also be tested as mediator of the optimism-adjustment relationship, as it has been associated with both optimism and adjustment in African American women and men (Mattis et al., 2003; Mattis et al., 2004).

The findings reported here are consistent with studies showing that social support buffers the negative impact of racism-related stress and acute economic stress among African American women (Ennis et al., 2000; Utsey et al., 2006). While low optimism differs from stress related to racism or economic loss, women with lowered optimistic expectancies experience greater stress and difficulty during cancer diagnosis, treatment, and recovery (Carver et al., 2005; Friedman et al., 2006; Schou et al., 2005). These data suggest that social support serves as an important resource when optimism is low. The buffering effect of social support was significant across several measures of adjustment including psychological distress, psychological well-being, and psychosocial functioning. We recognize that these measures are significantly correlated, but it is also important to note that each measure represents different aspects of adjustment. For example, data show that positive emotion and distress frequently co-occur during chronic stress, and positive and negative emotion may represent independent constructs rather than opposite ends of a continuum (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000).

In contrast to findings for psychological and psychosocial adjustment, social support was not associated with physical functioning and social support did not buffer the negative relationship between optimism and physical functioning. These findings are consistent with results reported by Helgeson and colleagues (2004) in a study of psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. Social support predicted psychological adjustment, but it did not predict physical adjustment after accounting for the effects of age, number of positive lymph nodes, and other personal resources (e.g., self-esteem, body image, and personal control). For African American cancer survivors, data suggest that the most salient factors impacting physical functioning include more extensive cancer treatment and comorbid health conditions (Deimling et al., 2002).

The interaction between optimism and social support accounted for an additional 4% of the variance in psychological and psychosocial adjustment. While the magnitude of this effect is modest, these findings provide valuable insight into the processes associated with adjustment in African American women following cancer treatment. These results suggest that social support may compensate for low optimism. Women with high levels of social support experienced better adjustment even when optimism was low. In contrast, among women with high levels of optimism, increasing social support did not provide an added benefit. These data suggest that interventions may not need to target both optimism and social support to improve adjustment, as women may be able to achieve better outcomes through multiple avenues.

There has been recent interest in testing whether intervention techniques can increase optimism in individuals with cancer. Antoni and colleagues (2001) tested the efficacy of a 10-week group cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Optimism increased over time among women in the intervention group, but levels of optimism did not change among women in the control group. A recent study with breast and colorectal cancer patients tested the efficacy of an intervention addressing existential issues (Lee et al., 2006). This intervention focused on using coping strategies that enhance meaning in life. Cancer patients who received the intervention showed a 9% increase in optimism, but individuals in the control group showed no change in optimism. While these studies suggest that interventions can increase optimism, maintaining increases in optimistic expectancies may be difficult. Mattis and colleagues (2003) point out that African Americans continually cope with challenges caused by racism and inequitable social conditions. For example, in a recent focus group study with breast cancer patients (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004), African American women expressed fears and concerns about experiencing racism within the healthcare system.

Increasing perceptions of available social support may contribute to better adjustment, especially for women with low optimism. Interventions aimed at increasing social support have reported mixed results (Helgeson, & Cohen, 1996; Hogan et al., 2002). However, recent data suggest that particular intervention techniques may yield benefits for women with breast cancer. Andersen and colleagues (2004) found improved perceptions of support among breast cancer patients participating in a psychological group-based intervention. This intervention included specific strategies (e.g., assertive communication training) for improving support from women’s existing social support networks. Tailoring psychological group-based interventions to address the concerns of African American women could yield important benefits. African American women report that breast cancer is viewed as a White women’s disease and there is a lack of support and understanding for the unique experiences of African American breast cancer patients (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004; Henderson et al., 2003). Moreover, African American cancer patients report that receiving information and advice from other African American cancer survivors is a valuable source of support (Hamilton & Sandelowski, 2004).

The current study provides new information about optimism, social support, and adjustment in cancer patients, but these findings need to be viewed within the particular circumstances of this study. First, this study included a single assessment. The use of a single assessment prohibits inferences about causality or the relationships between these variables over time. For example, the correlational study design makes it impossible to determine whether optimism influenced psychological adjustment or vice versa. Second, it is important to note that all of the variables were assessed using written self-report measures that were completed during a single assessment, which raises possible concerns over common method bias in the estimation of the hypothesized relationships (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Third, like the majority of studies examining optimism and social support in cancer patients, only breast cancer patients were enrolled. We do not know the generalizability of these findings to African American men, patients with other disease sites, or patients with more advanced disease. Finally, overall women reported high levels of adjustment, social support, and optimism, which may limit the generalizability of these findings to more distressed patients. The data were examined to determine if outliers or violations of normality were present, but no outliers or significant violations of normality assumptions were identified.

When interpreting the results of this study, it is also important to consider that the women in this sample agreed to participate in a randomized clinical trial of a psychological intervention. Women were asked to participate in a support group for African American women that aimed to provide education and counseling with regard to breast cancer. As described to women, the primary goal of this study was to test whether a support group intervention for African American women could lead to improvements in quality of life. Similar to other support group studies, we speculate that women who agreed to participate were more interested in seeking social support and had higher levels of adjustment compared to a population-based sample. Additional differences may exist between African American women who choose to participate in research and those who choose not to participate. Long-standing suspicion and mistrust of research that is related to past abuses by clinical researchers may serve as a barrier to research participation for many African American women (Corbie-Smith et al., 2002; Freimuth et al., 2001). Additional barriers may exist to participation in psychosocial research for African American women due to the social stigma associated with psychological services (Sanders-Thompson et al., 2004). Unfortunately, African American women have been significantly underrepresented in cancer research in general (Eastman, 1996; National Cancer Institute, 1999). While several factors may limit the generalizability of our findings, this study represents an important step in understanding the factors associated with adjustment among African American women with breast cancer.

In summary, our findings suggest that both optimism and social support are associated with better adjustment, and social support buffers the negative relationship between low optimism and psychological adjustment. Because the number of cancer patients living beyond treatment continues to grow, factors related to post-treatment adjustment are increasingly important (Aziz & Rowland, 2002). The factors that contribute to adjustment in African American cancer survivors need additional study, as findings from non-Hispanic White samples may not generalize to other patient populations (Ashing-Giwa et al., 1999; Meyerowitz et al., 1998). Experiences unique to African American patients may have an important impact on adjustment. Additional research with representative samples is needed to improve our understanding of the factors that contribute to positive outcomes for African American cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: the Nathan Cummings Foundation (#7955) and the American Cancer Society (JFRA615).

References

- Abend TA, Williamson GM. Feeling attractive in the wake of breast cancer: optimism matters, and so do interpersonal relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen BA, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, Glaser R, Emery CF, Crespin TR, Shapiro CL, Carson WE. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: A clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(17):3570–3580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa K, Ganz PA, Petersen L. Quality of life of African-American and White long-term breast carcinoma survivors. Cancer. 1999;85:418–426. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990115)85:2<418::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, Clayton S, Williams I, Hills D. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:408–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16:413–428. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. Effects of social comparison direction, threat, and self-esteem on affect, self-evaluation, and expected success. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1993;64:708–722. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz NM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivorship research among ethnic minority and medically underserved groups. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2002;29:789–801. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beder J. Perceived social support and adjustment to mastectomy in socioeconomically disadvantaged Black women. Social Work in Health Care. 1995;22:55–71. doi: 10.1300/j010v22n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Johnston M, Banks P, Fobair P. Sources of support and the physical and mental well-being of young women with breast cancer. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53:1513–1524. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland A, Cappeliez P. Optimism and neuroticism as predictors of coping and adaptation in older women. Personality & Individual Differences. 1997;22:909–919. [Google Scholar]

- Bourjolly JN, Hirschman KB. Similarities in coping strategies but differences in sources of support among African American and White women coping with breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2001;19:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Brissette I, Scheier MF, Carver CS. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:102–111. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Pozo-Kaderman C, Harris SD, Noriega V, Scheier MF, Robinson DS, Ketcham AS, Moffat FL, Clark KC. Optimism versus pessimism predicts the quality of women’s adjustment to early stage breast cancer. Cancer. 1994;73:1213–1220. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940215)73:4<1213::aid-cncr2820730415>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Smith RG, Antoni MH, Petronis VM, Weiss S, Derhagopian RP. Optimistic personality and psychosocial well-being during treatment predict psychosocial well-being among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2005;24:508–516. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E. Cultural influences on optimism and pessimism: differences in western and eastern construals of self. In: Chang E, editor. Optimism and pessimism: implications for theory, research, and practice. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Hoberman HM. Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1983;13:99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deimling GT, Schaefer ML, Kahana B, Bowman KF, Reardon J. Racial differences in health of older-adult long-term cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2002;20:71–94. doi: 10.1300/J077v20n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine D, Parker PA, Fouladi RT, Cohen L. The association between social support, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and adjustment following an experimental cancer treatment. Psychooncology. 2003;12:453–462. doi: 10.1002/pon.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougall AL, Hyman KB, Hayward MC, McFeeley S, Baum A. Optimism and traumatic stress: The importance of social support and coping. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2001;31:223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman P. NCI hopes to spur minority enrollment in prevention and screening trials Journal of the. National Cancer Institute; 1996. pp. 88pp. 236–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ek E, Remes J, Sovio U. Social and developmental predictors of optimism from infancy to early adulthood. Social Indicators Research. 2004:69, 219–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis NE, Hobfoll SE, Schroder KEE. Money doesn’t talk, it swears: how economic stress and resistance resources impact inner-city women’s depressive mood. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:149–173. doi: 10.1023/A:1005183100610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist. 2000;55:746–654. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth VS, Quinn SC, Thomas SB, Cole G, Zook E, Duncan T. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LC, Kalidas M, Elledge R, Chang J, Romero C, Husain I, Dulay M, Liscum KR. Optimism, social support, and psychological functioning among women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:595–603. doi: 10.1002/pon.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedzinska AS, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA, Rowland JH. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:39–51. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, Winn RJ. The role of informal and formal social support networks for patients with cancer. Cancer Practice. 1997;5:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JB, Sandelowski M. Types of social support in African Americans with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2004;31:792–800. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.792-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen K, Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Scheier MF, Raitakari OT, Pulkki L, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L. Socioeconomic status in childhood and adulthood: associations with dispositional optimism and pessimism over a 21-year follow-up. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1111–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychology. 1996;15:135–148. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H. Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychology. 2004;23:3–15. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson PD, Gore SV, Davis BL, Condon EH. African American women coping with breast cancer: a qualitative analysis. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2003;30:641–647. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.641-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BE, Linden W, Najarian B. Social support interventions: Do they work? . Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:381–440. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MO, Jackson PB, Powell B, Steelman LC. Color-blind: the treatment of race and ethnicity in social psychology. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2000;63:352–364. [Google Scholar]

- Jennrich R, Sampson P. Rotation for simple loadings. Psychometrika. 1968;31:313–323. doi: 10.1007/BF02289465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkeila K, Kivela S, Suominen S, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M, Sundell J, Helenius H, Koskenvuo M. Childhood adversities, parent-child relationships and dispositional optimism in adulthood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004;39:286–292. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0740-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V, Cohen SR, Edgar L, Laizner AM, Gagnon AJ. Meaning-making intervention during breast or colorectal cancer treatment improves self-esteem, optimism, and self-efficacy. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:3133–3145. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Psychological distress among Black and White Amercians: differential effects of social support, negative interaction, and personal control. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:390–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Wortman CB, Kusulas JW, Hervig LK, Vickers RR. Distinguishing optimism from pessimism: relations to fundamental dimensions of mood and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:1067–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Fontenot DL, Hatcher-Kay CA. Religiosity, racism, and dispositional optimism among African Americans. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:1025–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Fontenot DL, Hatcher-Kay CA, Grayman NA, Beale RL. Religiosity, optimism, and pessimism among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30:187–207. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz BE, Richardson J, Hudson S, Leedham B. Ethnicity and cancer outcomes: behavioral and psychosocial considerations. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;123:47–70. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.123.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CE, Prelow HM, Chen WW, Yackel ME. Coping and social support as mediators of the relation of optimism and depressive symptoms among Black college students. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32:72–86. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. What proportion of participants in NCI treatment trials belong to racial and ethnic minority groups? National Cancer Institute; 1999. NCI-supported cancer clinical trials: Facts and figures. [serial online]. Available at http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/facts-and-figures/page2#B9 Accessed 17, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Caffey M, Deichelbohrer L, Schmidt L, Guziatek-Trojniak L, West S, Kershaw T, Mood D. The quality of life of African American women with breast cancer. Research in Nursing and Health. 1999;22:449–460. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(199912)22:6<449::aid-nur3>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL. Social support in patients’ and husbands’ adjustment to breast cancer. Nursing Research. 1988;36:221–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1:115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Parker PA, Baile WF, De Moor C, Cohen L. Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12:183–193. doi: 10.1002/pon.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. The future of optimism. American Psychologist. 2000;12:119–132. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J, Posakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter LS, Clayton MF, Belyea M, Mishel M, Gil KM, Germino BB. Predicting negative mood state and personal growth in African American and White long-term breast cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;31:195–204. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3103_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Thompson VL, Bazile A, Akbar M. African Americans’ perceptions of psychotherapists. Professional Psychological Research and Practice. 2004;35:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Matthews KA, Owens JF, Magovern GJ, Lefebvre RC, Abbott RA, Carver CS. Dispositional optimism and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery: The beneficial effects on physical and psychological well-being. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1989;57:1024–1040. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.6.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schag CA, Ganz PA, Heinrich RL. Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System – Short Form (CARES-SF). A cancer specific rehabilitation and quality of life instrument. Cancer. 1991;68:1406–1413. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910915)68:6<1406::aid-cncr2820680638>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schou I, Ekeberg O, Sandvik L, Hjermstad MJ, Ruland CM. Multiple predictors of health-related quality of life in early stage breast cancer. Data from a year follow-up study compared with the general population. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14:1813–1823. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-4344-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelby RA, Lamdan RM, Siegel JE, Hrywna M, Taylor KL. Standardized versus open-ended assessment of psychosocial and medical concerns among African American breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2006:15, 382–397. doi: 10.1002/pon.959. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sherman AC, Walls JW. Gender differences in the relationship of moderator variables to stress and symptoms. Psychology and Health. 1995;10:321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Ware JE, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Psychological distress/well-being and cognitive functioning measures. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE Jr, editors. Measuring Functioning and Well-being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. pp. 102–142. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KL, Lamdan RM, Siegel JE, Shelby R, Moran-Klimi K, Hrywna M. Psychological adjustment among African American breast cancer patients: one-year follow-up results of a randomized psychoeducational group intervention. Health Psychology. 2003;22:316–323. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trunzo JJ, Pinto BM. Social support as a mediator of optimism and distress in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:805–811. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Lanier Y, Williams O, III, Bolden M, Lee A. Moderator effects of cognitive ability and social support on the relation between race-related stress and quality of life in a community sample of Black Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:334–346. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Ponterotto JG, Reynolds AL, Cancelli AA. Racial discrimination, coping, life satisfaction, and self-esteem among African Americans. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2000;78:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Veit CT, Ware JE., Jr The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51:730–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E, Kessler RC. Perceived support, received support, and adjustment to stressful life events. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1986;27:78–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]