Abstract

Azido nitrobenzoxadiazole (NBD) was observed to undergo a ‘reduction’ reaction in the absence of an obvious reducing agent, leading to amine formation. In the presence of an excess amount of DMSO, a sulfoxide conjugate was also formed. The ratio of these two products was both temperature- and solvent-dependent, with the addition of water significantly enhancing the ratio of the ‘reduction’ product. Two intermediates of the azido-NBD reaction in DMSO were trapped and characterized by low-temperature EPR spectroscopy. One was an organic free radical (S=1/2) and another was a triplet nitrene (S=1) species. A mechanism was proposed based on the characterized free radical and triplet intermediates.

Keywords: NBD, Azide, Reduction, Nitrene, EPR

1. Introduction

Azido compounds are versatile molecules. They are being used extensively in both organic reactions and chemical biology. For example, the ‘click’ reaction between an azido group and an alkyne,1 including the copper catalyzed and copper-free ‘click’ reactions,2 are becoming a very important approach to DNA,3 protein,4 and glycan labeling5 among other applications. The azido group is known to undergo a variety of useful reactions, including the Schmidt reaction, the Curtius reaction, and other important ring-formation or ring-expansion reactions.6 Reduction of azides is not only a very efficient method for the preparation of amines,7 amides, and sulfonamides,8 but also a new approach for the quantitative fluorescence detection of hydrogen sulfide in aqueous solutions.9 Azido compounds are known to fragment under light and/or at elevated temperature and to generate nitrenes,10 which can undergo an insertion reaction with alkenes, yielding aziridines.11 Transition metals such as copper were also observed to facilitate the fragmentation.12 Understandably, reduction of the azido group normally requires a reducing agent. However, herein we report a case where azido-NBD was ‘reduced’ to its corresponding amine in the absence of an obvious reducing agent. Copper was observed to catalyze the reaction. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies were also performed to gain initial insight into the reaction process.

2. Results and discussion

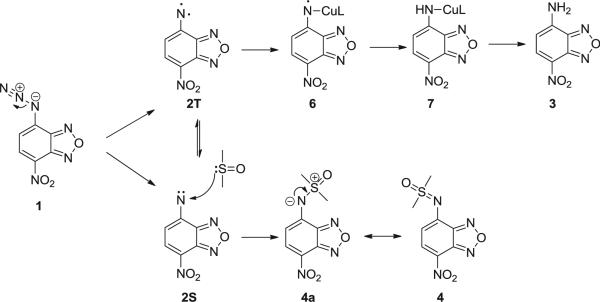

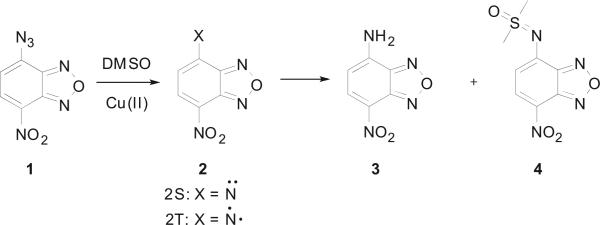

In our effort aimed at modifying the fluorescent dye nitrobenzoxadiazole (NBD), we synthesized azido-NBD (1) and conducted copper-mediated Huisgen cycloaddition at room temperature in a mixed solvent of water, DMF, and tert-butanol. Instead of the anticipated [2+3] cycloaddition product, we observed the formation of the ‘reduction’ product, amino-NBD (3) in 61% yield, although the reaction contained no obvious reducing agent. In the absence of any reducing agent, reduction of the azido group is nearly impossible unless the reaction went through a very reactive intermediate(s), which could ‘rob’ electrons or hydrogen atoms from otherwise ‘inert’ compounds. The formation of a nitrene intermediate (compound 2) can explain the product observed in this study. Specifically, nitrene formation followed by hydrogen abstraction would explain the formation of amino-NBD (3, Scheme 1). However, such fragmentations normally require either light or heat.13 To the best of our knowledge, room temperature azidoarene fragmentation in the absence of irradiation to the extent that a side product is readily isolated in high yield is considered unusual.

Scheme 1.

The copper catalyzed NB–Denitrene reaction in DMSO.

In order to eliminate the possibility that DMF was functioning as the reducing agent, we conducted the reaction using DMSO as the solvent. Interestingly, DMSO adduct 4 was obtained in addition to the reduction product 3. The nitrene intermediate formed by the fragmentation of an acyl azide group (e.g., Boc-N3) has been observed to undergo a transfer reaction leading to conjugation with sulfoxides and sulfides,14 but the aromatic nitrene transfer reaction has not yet been reported. This reaction could provide an alternative approach for the synthesis of the sulfoximines, which are very important intermediates in medicinal chemistry.15 This could also offer the possibility of fluorescent labeling of the sulfoxide group.

To achieve a further understanding of this unique reaction, a series of experiments were performed to study how several factors affect the reaction outcome. The reaction was carried out at both room and elevated temperatures (80 °C), with or without a transition metal ion (Cu(I), Cu(II), Ag(I), Fe(II), or Fe(III)) as the catalyst. The effects of EDTA, shielding the reaction from any light, and added H2O were also examined. 1H NMR spectroscopy was used to monitor the reaction progress. The results of the reactions under different conditions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Product analysis of the NBD–nitrene reaction in DMSOa

| Entry | Catalyst | Other | Solvent | Temp | 1 | 3 | 4b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | None | DMSO | rt | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| 2 | None | None | DMSO | 80 °C | 0 | 0.24 | 0.76 |

| 3 | CuCl | Dark | DMSO/H2O | rt | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0 |

| 4 | None | None | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0.29 | 0.55 | 0.16 |

| 5 | None | Dark | DMSO | 80 °C | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.34 |

| 6 | CuCl2 | None | DMSO | 80 °C | 0 | 0.25 | 0.75 |

| 7 | CuCl2 | Dark | DMSO | 80 °C | 0 | 0.26 | 0.74 |

| 8 | CuCl | None | DMSO | 80 °C | 0 | 0.32 | 0.68 |

| 9 | CuCl | Dark | DMSO | 80 °C | 0 | 0.39 | 0.61 |

| 10 | AgNO3 | None | DMSO | 80 °C | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.66 |

| 11 | AgNO3 | Dark | DMSO | 80 °C | 0.55 | 0.06 | 0.39 |

| 12 | CuCl2 | None | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.74 | 0.26 |

| 13 | CuCl2 | Dark | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.64 | 0.36 |

| 14 | CuCl | None | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.74 | 0.26 |

| 15 | CuCl | Dark | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0.07 | 0.69 | 0.24 |

| 16 | AgNO3 | None | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.70 | 0.30 |

| 17 | AgNO3 | Dark | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0.17 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

| 18 | FeCl3 | None | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0.29 | 0.53 | 0.17 |

| 19 | FeCl2 | None | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0.23 | 0.66 | 0.11 |

| 20 | None | EDTA, Dark | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0.71 | 0.19 | 0.10 |

| 21 | None | EDTA | DMSO/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.76 | 0.24 |

| 22 | None | EDTA, Dark | DMSO | 80 °C | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.29 |

| 23 | None | EDTA | DMSO | 80 °C | 0.1 | 0.47 | 0.43 |

Unless otherwise indicated, reactions were proceeded for 24 h with 10 mg of 1, 0.8 mL of DMSO-d6 or DMSO-d6/D2O 3:1, 20 mmol % of catalyst. ‘Dark’ refers to protecting from light using foil.

Ratio is determined by the crude 1H NMR spectra.

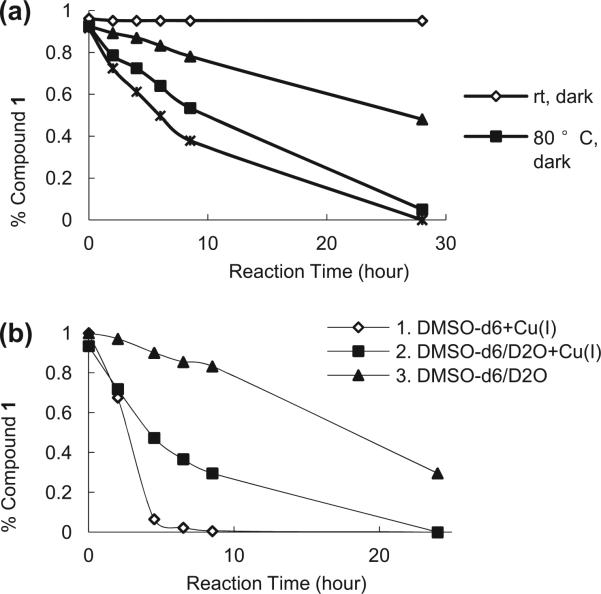

When comparing reaction outcomes in entries 1 and 5 as well as 3 and 15, one can see that the reaction was temperature-dependent. In DMSO, the reaction gave a 16% conversion at room temperature in 24 h without catalyst (Table 1, entry 1), whereas full conversion was achieved in 24 h at 80 °C (entry 2). It also seems that ordinary room-light makes a difference. For example, at 80 °C the reaction achieved full conversion under light (entry 2), but only about 50% conversion when the reaction was run in the dark (entry 5). Subsequent reactions in the presence of metal ions (entries 10 and 11, 16 and 17) or EDTA (entries 20 and 21, 22 and 23) also indicate room-light affords reaction acceleration. It was found that Cu(II) and Cu(I) (under N2 atmosphere) seem to facilitate the reaction. Comparing the results from entries 7 and 9 to that of entry 5 in Table 1, one can see that the addition of copper significantly accelerates the reaction (This was also confirmed in Fig. 1b.). In the absence of any metal ions and in the dark, 48% of the starting material remained at the end of the reaction (entry 5), whereas all starting material disappeared when the same reaction was carried out in the presence of Cu(II) (entry 6) or Cu(I) (entry 9). However, addition of either Cu(II) or Cu(I) did not seem to affect the product ratio significantly. For example, Cu(II)-facilitated reactions gave a 3:1 ratio between 4 and 3 independent of whether the reaction was run in the dark. This ratio is the same as the reaction under light and in the absence of any metal ions (entry 2). We also tested the effect of silver ions. It was surprising to find that Ag actually inhibits the reaction. For example, heating 1 at 80 °C in DMSO led to the complete disappearance of the starting material after 24 h. However, the same reaction in the presence of AgNO3 still had 11% starting material after 24 h. The specific reason for this inhibition is not clear.

Fig. 1.

Time dependent decrease of 1 as a percentage of the initial concentration under different reaction conditions. (a) Reaction was performed in DMSO-d6/D2O in the presence of Cu(I). (b) Reaction was performed at 80 °C in the dark. DMSO-d6/D2O ratio was 3:1. Cu(I) was 20 mmol %.

In all the above reactions, the DMSO adduct 4 was the major product. However, upon addition of water, reaction seems to slow down (entry 2 vs 4) leading to the reduction product 3 being the major component. For example, when the reaction was performed in a solvent system of DMSO/H2O (3:1), the ratio of the two isolated products 3 and 4 was found to be around 3:1, while the reaction in dry DMSO gave a 1:3 ratio. Again, addition of either Cu(I) or Cu(II) accelerated the reaction but did not seem to alter the ratio of the reduction product and the DMSO adduct. For example, in the presence of water, the ratio between 3 and 4 was approximately 3:1 with or without added Cu (at the valence state of I or II) (entries 12 and 14). When carried out in the dark, this ratio decreased slightly. Such results suggest that copper ion addition did not fundamentally alter the reaction pathway. Interestingly, Ag(I) addition accelerated the reaction when water was present. For example, in entry 2, 29% of starting material remained after 24 h of reaction; while the same reaction in the presence of Ag(I) resulted in complete conversion of the starting material to the product. In the meantime, addition of Ag(I) also led to a decrease of the ratio between 3 and 4 from 3:1 to about 2:1. For the reactions in the presence of water, we also studied the effect of Fe(III). It was found that Fe(III) played very little role in the reaction (entries 19 and 20).

In order to examine the catalytic effects by trace amount of metal ions present in water, we also performed experiments by adding EDTA (entries 20–23). The reaction was found to be incomplete (29% conversion) in the presence of EDTA while in the dark (entry 20) at 80 °C. A comparison of entries 20 and 21 or 22 and 23 also suggest that light can accelerate the reaction. This series of studies suggest that (1) light and heat can accelerate the reaction; (2) Cu(I) and Cu(II) can also accelerate the reaction; (3) water can slow down the reaction rate, while altering the ratio of the product by facilitating the formation of reduction product; (4) Ag(I) and Fe(II or III) has little or mixed effect on the reaction, (5) trace amount of ions in the buffer and/or DMSO plays an important role in accelerating the reaction; and (6) in the absence of light and metal ion catalyst (EDTA addition), the reaction is slow even at an elevated temperature (80 °C).

In order to achieve a more in depth understanding of the reaction profiles, the effects of temperature, catalyst, and solvent on the reaction rates were examined by monitoring the disappearance of the starting material using 1H NMR every 2 h for 8 h, and then at 24 h or 28 h point (Fig. 1). In Fig. 1a, the results confirmed the acceleration effects by both heat and light, as one would expect. As is shown in Fig. 1b, the highest reaction rate was achieved in DMSO in the presence of Cu(I), while the reaction slowed down when carried out in a mixed solvent of DMSO-d6/D2O (3:1). When the reaction was carried out in DMSO-d6/D2O without a catalyst, the reaction went slowly and was not complete within 24 h. These results further support that heat, light or catalyst can indeed accelerate the reaction. At the same time, water addition obviously reduced the reaction rate. It is interesting to note that although water decreases the overall reaction rate, its presence led to an increased proportion of the reduction product 3.

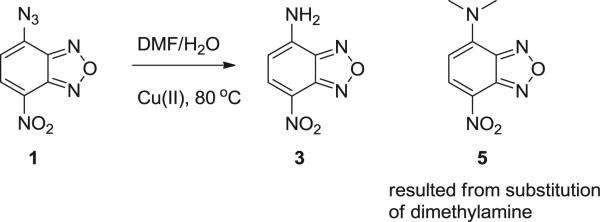

When the reaction was performed in DMF, no corresponding solvent adduct was observed. The ‘reduction’ product 3 was the major component (ca. 90% yield) (Scheme 2). Compound 5 was observed as a minor product, which was presumably formed from the substitution reaction between compound 1 and the free dimethylamine present in DMF. Control reactions using dimethylamine confirmed this aspect. Product analysis results are shown in Table 2.

Scheme 2.

The NBD–enitrene reaction in DMF.

Table 2.

Product analysis of the NBD–nitrene reaction in DMFa

| Entry | Catalyst | Other | Solvent | Temp | 1 | 3 | 5b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | None | DMF | rt | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.06 |

| 2 | None | None | DMF/H2O | 80 °C | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.24 |

| 3 | CuCl | None | DMF/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.93 | 0.07 |

| 4 | CuCl2 | None | DMF/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.92 | 0.08 |

| 5 | CuCl2 | Dark | DMF/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.91 | 0.09 |

| 6 | AgNO3 | None | DMF/H2O | 80 °C | 0 | 0.83 | 0.17 |

Reactions were carried out for 24 h with 10 mg of 1, 0.8 mL of DMF or DMF/H2O 3:1, 20 mmol % of catalyst.

Ratio is determined by the crude 1H NMR spectra.

When compared with the reactions in DMSO, the reaction went slower in DMF with a conversion of 38% at room temperature after 24 h (Table 2, entry 1). When heated to 80 °C, 82% conversion was achieved (entry 2). The presence of transition metal catalysts in addition to heating drove the reaction to completion (entries 3–6), even when the reaction was performed in dark (entry 5). It is worth noting that percentage of compound 5 was higher in the absence of an added catalyst (entries 1 and 2). This is easy to understand since the relative reaction rates of the substitution reaction and nitrene formation process were altered with the addition of a catalytic metal ion. Comparison of entries 1 and 2 also suggest that H2O slowed down the reaction in DMF as well.

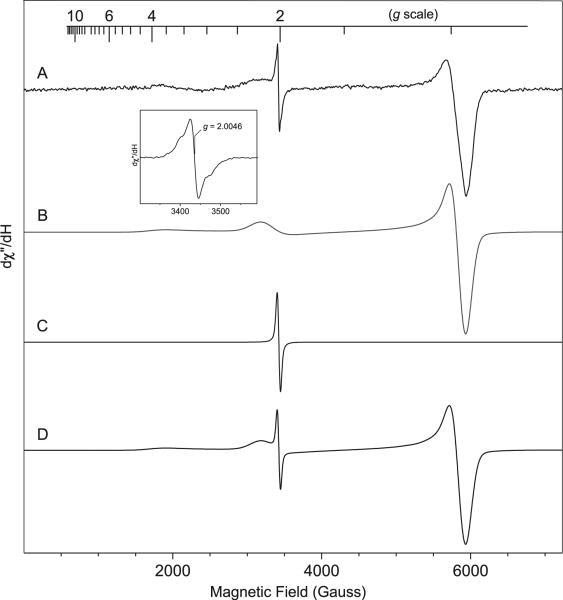

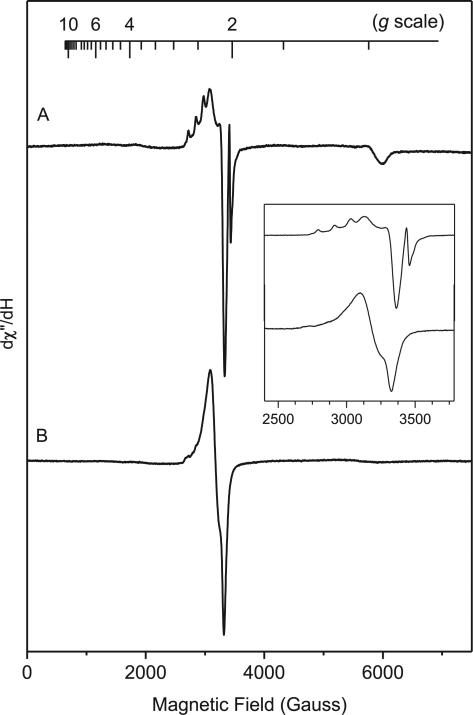

In order to verify the reactive species involved in the reaction, we also conducted EPR studies. Since azido groups are known to fragment and generate nitrenes, it is reasonable to assume that a nitrene intermediate could be possibly involved in this reaction. The observation of the DMSO adduct of NBD also supports nitrene formation from azido-NBD. After heating for 20 min at 80 °C, the azido-NBD solution (80 mM) in DMSO and water (3:1 ratio) yielded a broad signal covering 5360 Gauss range with three well-resolved resonance components and an anisotropic S = 1/2 EPR signal at g=2.0046 (Fig. 2A). The broad EPR signal can be simulated by an S=1 triplet species (Fig. 2B) with a D value of 0.6263±0.0010 cm−1 and three principal g values of 1.99, 2.033, and 2.033. The large zero-field splitting (ZFS) parameter D is characteristic of triplet nitrenes.16 However, the observed D value of the azido-NBD reaction was close to but also noticeably smaller than that of the triplet ground state of p-nitrophenyl nitrene (0.9833 cm−1).17 It is known that π delocalization reduces the density of the π-electron on the nitrogen atom and, thus, reduces the value of D.18 The D value of nitrenes was noted to be proportional to the inverse cube of the average distance between the two unpaired electrons; the smaller D value indicated greater delocalization of the spin density away from the nitrogen atom.19

Fig. 2.

Low-temperature (10 K) continuous-wave X-band EPR spectrum of azido-NBD (80 mM) in DMSO and H2O. (A) EPR spectrum of azido-NBD obtained at 10 K, microwave frequency 9.64 GHz, microwave power 1 mW, modulation frequency 100 kHz, modulation 5 G, (B) simulation of the triplet state, (C) simulation of the free radical, and (D) simulated EPR spectrum by combining B and C. The inset is a magnification of the g=2 region, which showed a free-radical species with partially resolved hyperfine structure.

The S=1/2 EPR signal at g=2.0046 had additional hyperfine structures (Fig. 2), consistent with an organic species with free-radical characters. Simulation of the EPR spectrum confirmed the presence of multiple species and enabled us to estimate the relative ratio between the two EPR-active species (Fig. 2). The free-radical signal accounted for about 5–8% of the total spin, whereas that the triplet EPR signal accounted for the majority of the total spin (92–95%). Because the signal was extremely broad and there is no spin standard available, it was not possible to precisely determine the absolute concentration of the triplet intermediate based on the EPR signal strength. Integration of the simulated EPR signals suggested that the free-radical signal intensity was about 1/12 to 1/15 of the triplet signal. Thus, the total EPR-active species was a few percent of the total azido-NBD. If these were the reactive species, they would explain the slow reaction rate.

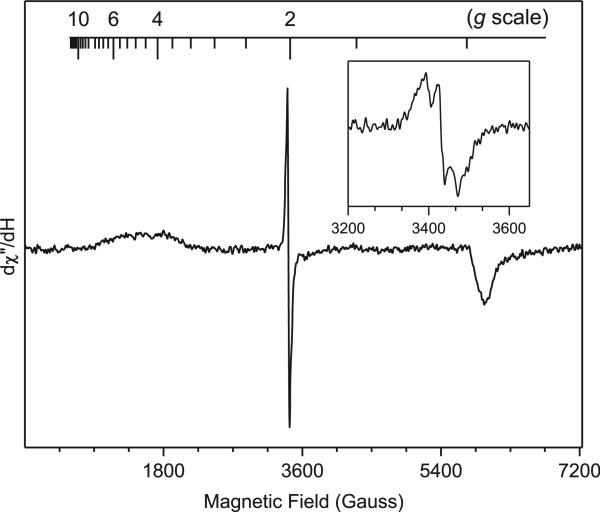

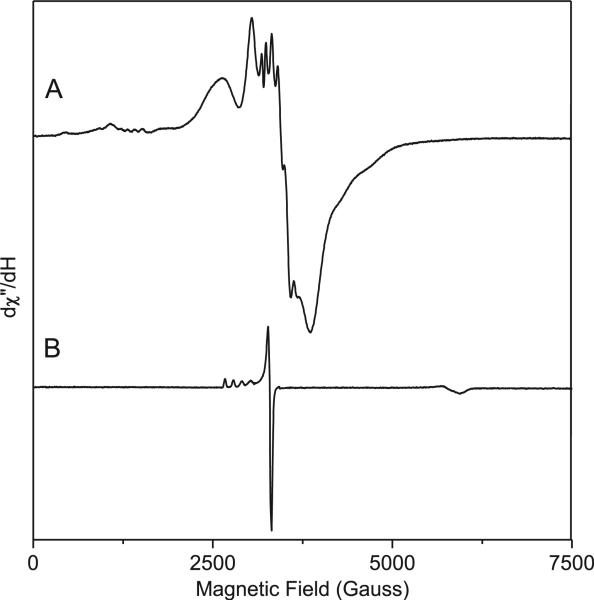

In the absence of water, the triplet EPR signal was more axial and less rhombic (Fig. 3). A notable difference was that the ratio of S=1/2 and S=1 species had increased by one order of magnitude when water was absent from the reaction mixture. The presence of water caused about 10-fold increase of the ratio between reduction product 3 and DMSO adduct 4 in the same time period (Table 1). Since the ‘reduction’ of the nitrene has to go through a radical intermediate 6 (Scheme 3), the suppression of radical species by water might be due to the accelerated conversion of the radical into the reduction product 3.

Fig. 3.

X-band EPR spectrum of azido-NBD (80 mM) in DMSO. Instrument conditions were the same as those in Fig. 2. The inset magnifies the g=2 region.

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanisms of the azido-NBD ‘reduction’ reaction leading to the amine product via a triplet intermediate and DMSO conjugate formation.

We have also characterized the Cu(II)-mediated catalytic process by EPR spectroscopy. Fig. 4 shows EPR spectra of CuCl2 (1 mM) in the presence and absence of azido-NBD in DMSO (heated for 20 min at 80 °C), respectively. In the presence of azido-NBD, the Cu(II) ion showed an axial EPR spectrum with copper hyperfine splitting in the parallel region similar to that observed in regular copper coordination compounds (Fig. 4A). The A∥ value was measured to be 130 G, which was in the typical type II copper range with N or N/O ligands and much larger than that of type I copper with sulfur ligands. In contrast, in the absence of azido-NBD, the EPR spectrum did not show a resolved hyperfine splitting in the parallel region at various temperatures (5–30 K) regardless of strong and weak microwave power applied (Fig. 4B). The copper EPR signal was more difficult to saturate by applied microwave power when azido-NBD was present, suggesting that NBD, or an intermediate derived from it, binds to Cu(II) during the catalytic reaction in DMSO.

Fig. 4.

X-band EPR spectra of Cu(II) (1 mM) and azido-NBD (80 mM) in DMSO during the Cu(II)-mediated catalytic reaction (A) and Cu(II) in DMSO in the absence of azido-NBD (B). The inset compares the resonances at the g=2 region.

The divalent metal ion caused a significant increase of both the S=1/2 and S=1 species, thereby providing further evidence that these EPR-active species were the reactive intermediates. The EPR spectra in the absence and presence of water (Fig. S1) both showed resolved hyperfine splitting and were distinct from the spectrum without azido-NBD. Adding H2O to the azido-NBD/DMSO/Cu(II) mixture caused the formation of a Cu(II) complex with a spectrum reminiscent of that from of complex. This may result in the deactivation of copper catalyst, which may explain why the addition of H2O slows down the reaction. The free radical to triplet ratio was significantly reduced in the presence of water.

Although the g=2.0046 EPR species partially overlapped the copper signal, it was still possible to estimate its intensity from the signal amplitude (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

EPR spectra of Cu(II) and azido-NBD in DMSO in the absence (A) and presence of water (B).

When the reaction was carried out in DMF, copper exhibited a complex EPR signal consistent with a metal-bound triplet with hyperfine splitting patterns in both the parallel and perpendicular regions (Fig. 6). The control sample, in which azido-NBD was absent, showed only one type II copper. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to believe that the contribution of the two possible resonance structures of amide in DMF has caused two distinct forms of the Cu(II)/azido-NBD complex. The free-radical signal was almost completely suppressed, indicating water-induced fast consumption of the free radical.

Fig. 6.

EPR spectra of Cu(II) and azido-NBD in DMF (A) and Cu(II) in DMF without azido-NBD (B).

As to the detailed mechanism of formation for the two products, one can postulate the formation of the NBD-nitrene 2 after the loss of a nitrogen molecule, thermally, photochemically, and/or upon metal ion catalysis (Scheme 3). Given the nature of the two isoforms of nitrene 2 (singlet 2S and triplet 2T), it is proposed that the DMSO adduct 4 was produced from the additional reaction between the singlet nitrene 2S and DMSO. It is also proposed that the formation of product 3 was from the triplet state, through a radical-type mechanism by hydrogen abstraction. A copper–nitrene radical intermediate 6, which is evidenced by EPR spectrum, can be generated as a stabilized nitrene.

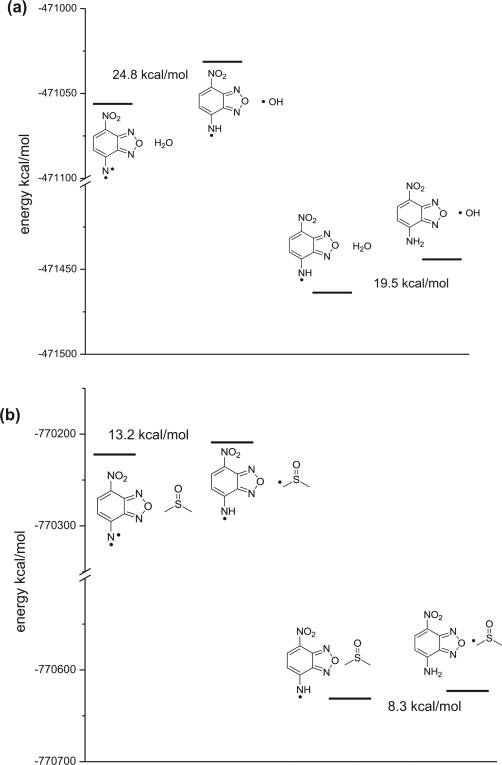

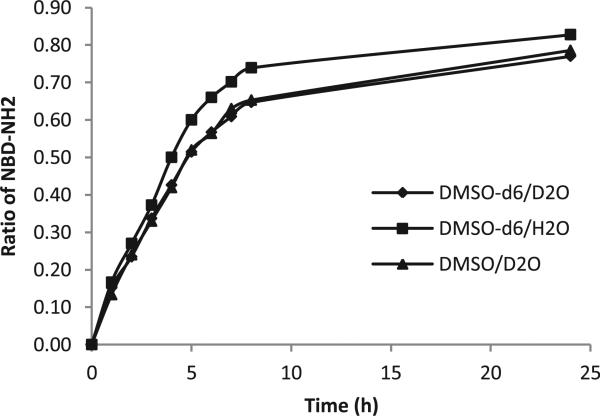

In the presence of water, compound 3 was the major product. One possible way to explain the enhanced ‘reduction’ product ratio in the presence of water is that H2O can donate a H atom and thus accelerates the proton abstraction pathway. However, given the reactive nature of hydroxy radicals, we thought that this was an unlikely scenario. We conducted quantum mechanics (QM) calculation to understand the relative energetics in a proton abstraction process. We chose to perform the calculation at the B3LYP/6-31+G* level because it is a cost-effective method and was already used to model the free-radical propagation reaction steps.20 Due to the extremely high energy of the hydroxyl radical, there would be an energy difference of about 20–25 kcal/mol between the starting materials and the products if H2O indeed acted as an H-donor (Fig. 7). The energy difference would be much smaller at 8–13 kcal/mol if DMSO acted as a H-donor. Thus in a mix-solvent system, one would expect that DMSO be the dominant donor in a hydrogen-abstraction process and water addition would not be expected to perturb the production distribution ratio by simply providing a large quantity of a hydrogen donor (water). In order to further examine the possibility for the solvents to act as hydrogen donors, a H NMR experiment was also performed to test the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) using mixed solvent systems DMSO-d6/D2O, DMSO-d6/H2O and DMSO/D2O. However, no obvious KIE was observed for either DMSO or H2O from the formation of NBD-NH2 (Fig. 8). Such results are consistent with the formation of the reactive nitrene intermediate(s) being the rate-limiting step. Although we could not rule out the possibility of water acting as H-donors, the effect of H2O is more likely to be due to its ability to affect the distribution of the two nitrene species.

Fig. 7.

Quantum mechanics calculation on the reaction between nitrene and H2O (a) and DMSO (b).

Fig. 8.

Kinetic isotope effect on formation of NBD–NH2.

3. Conclusion

In summary, an unusual ‘reduction’ of an arylazide was observed and examined in detail. The arylazide was reduced to the corresponding amine 3 in the absence of an obvious reducing agent. In the presence of DMSO as a solvent, a DMSO adduct 4 was also formed. This reaction was facilitated by light, the addition of copper catalyst, and elevated temperature. In addition, solvents significantly affect product distribution with the addition of water substantially enhancing the proportion of the ‘reduction’ product 3. EPR spectroscopy provides solid evidence for the presence of a triplet nitrene 2T and a radical intermediate, which become more pronounced during reaction at higher temperature or in the presence of copper catalyst. Based on the results from 1H NMR and EPR spectroscopic studies, a possible mechanism has been proposed. Considering the significant change of the product distribution in different solvents, one can envision that the ratio of the reactive intermediates might be affected by the solvents. The results presented offer insight into possible reactions that arylazido compounds can undergo, provide an alternative preparation method for sulfoximines, and offer the possibility of fluorescent labeling of the sulfoxide group.

4. Experimental section

4.1. General experimental methods

Unless otherwise noted, all reagents were purchased from Aldrich and used without further purification. All reactions were performed under the protection of N2, except for the NMR experiments. Thermometers were not calibrated. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 NMR spectrometer. IR was recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum One FT-IR Spectrometer. Mass spectral analyses were performed on an ABI API 3200 (ESI-Triple Quadruple). Low-temperature X-band EPR first derivative spectra were recorded in perpendicular mode (TE102) on a Bruker ER200D spectrometer at 100-kHz modulation frequency using a 4116DM resonator. Sample temperature was maintained with an ITC503S temperature controller, an ESR910 liquid helium cryostat, and LLT650/13 liquid helium transfer tube (Oxford Instruments, Concord, MA). EPR spectral simulations were performed by using a Windows-based spin simulation program and a dedicated triplet simulation program, both of which were written by Dr. Andrew Ozarowski.

4.2. Preparation of azido-NBD (1)

Sodium azide (584 mg, 9.04 mmol, 3.0 equiv) was dissolved in 56 mL of H2O/acetone (1:1, v/v) in a 250 mL round bottom flask. Then a solution of NBD chloride (600 mg, 3.01 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in acetone (28 mL) was added into the flask dropwise at room temperature with stirring. The reaction mixture turned from light yellow to yellow-brown within 5 min. After 10 min, the reaction mixture was concentrated under vacuum to remove acetone. The yellow precipitates were filtered out and washed with water (20 mL×3) to give 1 as yellow crystals (576 mg, 93%), which were used for the next step without purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=8.49 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.04 ppm (d, J=8.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ=145.9, 143.7, 137.8, 133.9, 131.8, 116.8 ppm; IR 3093, 2113, 1631, 1527, 1444, 1279, 996 cm−1; mp 100–101 °C (H2O/acetone); HRMS (ES+), m/z calculated for C6H2N6O3Na: 229.0086, found: 229.0079 [M+Na]+.

4.3. General procedure of the NBD–nitrene reaction in the presence of copper

In an oven-dried 5-mL round bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, we added azido-NBD (1, 10 mg, 0.05 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and CuCl2 (1.2 mg, 0.01 mmol, 0.2 equiv). The system was degassed using a vacuum pump and backfilled with Ar. Then solvent (DMSO/H2O 0.6 mL/0.2 mL) (or DMSO (0.8 mL)) was added into the system. The reaction mixture was heated at 80 °C with stirring for 24 h. Then the reaction solution was diluted with ethyl acetate (30 mL) and washed with H2O (10 mL×3) and brine (10 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Solvent was evaporated to yield the crude product, which was purified by flash chromatography (silica gel, eluent: hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1) to give pure NBD–NH2 (3) as orange-red needles and NBD–DMSO (4) as orange crystals. NBD–NH2 (3): 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ=8.87 (br, 1H), 8.48 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.39 ppm (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ=147.1, 144.24, 144.20, 137.0, 121.8, 101.8 ppm; mp 238H), 6.39 ppm (d, J 8.8 Hz, 1H);239 °C (methanol); IR 3424, 3334, 2922, 2496, 1640, 1250 cm−1; HRMS (ES+), m/z calculated for C6H5N4O3: 181.0362, found: 181.0360 [M+H]+. NBD–DMSO (4): 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6): δ=8.54 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.65 ppm (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, acetone-d6): δ=150.1, 148.4, 145.3, 136.1, 128.1, 111.5, 42.5 ppm; mp 212–214 ° C (ethyl acetate), IR 3005, 2923, 1613, 1515, 1294, 1108, 830 cm−1; HRMS (ES+); m/z calculated for C8H8N4O4S: 257.0345, found: 257.0348 [M+H]+. In DMF as the solvent, NBD–NMe2 (5) 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6): δ=8.49 (d, J=9.2 Hz, 1H), 6.39 (d, J=9.2 Hz, 1H), 3.71 ppm (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ=147.1, 145.3, 145.2, 136.7, 102.7 ppm; mp 214–216 °C (ethyl acetate); HRMS (ES+); m/z calculated: 209.0675, found: 209.0670 [M+H]+.

4.4. Reaction monitoring using 1H NMR spectroscopy

Azido-NBD (1, 7 mg, 0.034 mmol, 1.0 equiv) (and CuBr (1.0 mg, 0.007 mmol, 0.2 equiv)) was added into an NMR tube. Then solvent (0.4 mL, DMSO-d6 or DMSO-d6/D2O 3:1) was added into the tube in dark, and the reagents were shaken well to mix in dark for less than 30 s. Then the 1H NMR spectra of reaction mixture were recorded every 2 h for 8 h, and after 24 h.

4.5. Computational studies

All calculations were performed using the Gaussian 03 program.21 Initial geometry optimizations and DFT calculations were carried out using the B3LYP22 with the standard 6-31+G* basis set.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Andrew Ozarowski and Jerzy Krzystek for providing us with a triplet simulation program and for helping with spectral analyses. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants (GM084933 and GM086925 to B.W.) and the National Science Foundation (MCB0843537 to A.L.). K.H.D. acknowledges the fellowship support from Southern Regional Education Board (SREB). W.C. acknowledges an MBDAF fellowship from Georgia State University; and H.P. also acknowledges the financial support from GSU University Fellowship for Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics and an MBDAF fellowship.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2013.04.091.

References and notes

- 1.a Huisgen R. Angew. Chem. 1963;75:604–637. [Google Scholar]; b Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baskin JM, Prescher JA, Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Chang PV, Miller IA, Lo A, Codelli JA, Bertozzi CR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:16793–16797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Salic A, Mitchison T. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:2415–2420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dai CF, Wang LF, Sheng J, Peng HJ, Draganov AB, Huang Z, Wang BH. Chem. Commun. 2011:3598–3600. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04546b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lin N, Yan J, Huang Z, Altier C, Yan J, Carrasco N, Suyemoto M, Johnson L, Fang H, Wang Q, Wang S, Wang B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1222–1229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d El-Sagheer AH, Brown T. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:1388–1405. doi: 10.1039/b901971p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vila A, Tallman KA, Jacobs AT, Liebler DC, Porter NA, Marnett LJ. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21:432–444. doi: 10.1021/tx700347w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Laughlin ST, Baskin JM, Amacher SL, Bertozzi CR. Science. 2008;320:664–667. doi: 10.1126/science.1155106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chang PV, Prescher JA, Sletten EM, Baskin JM, Miller IA, Agard NJ, Lo A, Bertozzi CR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:1821–1826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911116107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sawa M, Hsu TL, Itoh T, Sugiyama M, Hanson SR, Vogt PK, Wong CH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:12371–12376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605418103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Lang S, Murphy JA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;35:146–156. doi: 10.1039/b505080d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Benati L, Bencivenni G, Leardini R, Nanni D, Minozzi M, Spagnolo P, Scialpi R, Zanardi G. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2499–2502. doi: 10.1021/ol0606637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Corey EJ, Link JO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:1906–1908. [Google Scholar]; b Kazemi F, Kiasat AR, Sayyahi S. Phosphorus Sulfur. 2004;179:1813–1817. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omura K, Uchida T, Irie R, Katsuki T. Chem. Commun. 2004:2060–2061. doi: 10.1039/b407693a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Peng HJ, Cheng YF, Dai CF, King AL, Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, Wang BH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:9672–9675. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lippert AR, New EJ, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:10078–10080. doi: 10.1021/ja203661j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Peng H, Chen W, Wang B. In: Gasotransmitters: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Hermann A, Sitdikova GF, Weiger TM, editors. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: 2012. pp. 99–137. [Google Scholar]; d Peng H, Chen W, Cheng Y, Wang B. Sensors. 2012;12:15907–15946. doi: 10.3390/s121115907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Horner L, Christmann A. Angew. Chem. 1963;2:599–608. [Google Scholar]; b Moss RA, Platz MS, Jones M., Jr. Reactive Intermediate Chemistry. Wiley-Interscience; New Brunswick, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]; c Scriven EFV, Turnbull K. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:297–368. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller P, Fruit C. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2905–2919. doi: 10.1021/cr020043t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwart H, Kahn AA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:1950–1951. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a Lord SJ, Lee HL, Samuel R, Weber R, Liu N, Conley NR, Thompson MA, Twieg RJ, Moerner WE. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:14157–14167. doi: 10.1021/jp907080r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b He J, Chang J, Chen R, Wang Q. Chin. J. Pharm. 2002;33:425–426. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a Bergmeier SC, Stanchina DM. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:4449–4456. doi: 10.1021/jo970473x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bach T, KSrber C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5015–5016. [Google Scholar]; c Bach T, Köorber C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999:1033–1039. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moessner C, Bolm C. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2667–2669. doi: 10.1021/ol050816a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sander W, Grote D, Kossmann S, Neese F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4396–4403. doi: 10.1021/ja078171s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hebden JA, McDowell CA. J. Magn. Reson. 1971;5:115–133. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smolinsky G, Snyder LC, Wasserman E. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1963;35:576–577. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weil JA, Bolton JR. Electron Spin Resonance: Elementary Theory and Practical Applications. 2nd ed. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu XR, Pfaendtner J, Broadbelt LJ. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:6772–6782. doi: 10.1021/jp800643a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Laham A, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03, Revision C.02. Gaussian Inc.; Pittsburgh PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.a Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]; b Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.