Abstract

Ciliogenesis and cystogenesis require the exocyst, a conserved eight-protein trafficking complex that traffics ciliary proteins. In culture, the small GTPase Cdc42 co-localizes with the exocyst at primary cilia and interacts with the exocyst component Sec10. The role of Cdc42 in vivo, however, is not well understood. Here, knockdown of cdc42 in zebrafish produced a phenotype similar to sec10 knockdown, including tail curvature, glomerular expansion, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation, suggesting that cdc42 and sec10 cooperate in ciliogenesis. In addition, cdc42 knockdown led to hydrocephalus and loss of photoreceptor cilia. Furthermore, there was a synergistic genetic interaction between zebrafish cdc42 and sec10, suggesting that cdc42 and sec10 function in the same pathway. Mice lacking Cdc42 specifically in kidney tubular epithelial cells died of renal failure within weeks of birth. Histology revealed cystogenesis in distal tubules and collecting ducts, decreased ciliogenesis in cyst cells, increased tubular cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, increased fibrosis, and led to MAPK activation, all of which are features of polycystic kidney disease, especially nephronophthisis. Taken together, these results suggest that Cdc42 localizes the exocyst to primary cilia, whereupon the exocyst targets and docks vesicles carrying ciliary proteins. Abnormalities in this pathway result in deranged ciliogenesis and polycystic kidney disease.

Cilia are thin rod-like organelles, found on the surface of many eukaryotic cells, with complex functions in signaling, cell differentiation, and growth control. Cilia extend outward from the basal body, a cellular organelle related to the centriole. In kidney cells, a single primary cilium projects from the basal body, is nonmotile, and exhibits an axoneme microtubule pattern of 9+0. In the mammalian kidney, primary cilia have been observed on renal tubule cells in the parietal layer of the Bowman capsule, the proximal tubule, the distal tubule, and in the principal, but not intercalated, cells of the collecting duct.1

Multiple proteins that, when mutated, result in the development of polycystic kidney disease (PKD) have been localized to renal primary cilia. These include polycystin-1 and -2, the causal proteins in autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD) (reviewed by Smyth et al.2). Research into pkd2 function in zebrafish has further strengthened the idea that polycystin-2 functions in cilia. Knockdown of pkd2 by morpholino (MO)3–5 or in mutants5,6 produces phenotypes that are consistent with a role in cilia function, such as curved tails, pronephric cysts, and edema.

Although we are beginning to identify the roles ciliary proteins play in diverse biologic processes, relatively little is known about how these proteins are transported to the cilium.7 The exocyst, originally identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae,8 is a highly conserved 750-kD eight-protein complex known for the targeting and docking of vesicles carrying membrane proteins.9 It is composed of Sec3, Sec5, Sec6, Sec8, Sec10, Sec15, Exo70, and Exo84 (also known as EXOC1–8).10 Notably, in addition to being found near the tight junction, exocyst proteins were localized to the primary cilium in kidney cells.11,12 Sec10 and Sec15 are the most vesicle-proximal of the exocyst components. Sec10 directly binds to Sec15, which, in turn, directly binds Sec4/Rab8, a Rab GTPase found on the surface of transport vesicles. Sec10 then acts as a “linker” by binding the other exocyst components through Sec5.13 Our previous studies suggested that the exocyst would no longer be able to bind Sec15, and thereby target/dock transport vesicles, without Sec10, and would, instead, disintegrate and be degraded. Importantly, we showed that knockdown of Sec10 in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells abrogated ciliogenesis, while Sec10 overexpression enhanced ciliogenesis. Furthermore, Sec10 knockdown caused abnormal cystogenesis when the cells were grown in a collagen matrix and decreased the levels of other exocyst components and the intraflagellar transport protein 88. This was in contrast to knockdown of exocyst components Sec8 and Exo70, which had no effect on ciliogenesis, cystogenesis, or levels of other exocyst components.12 On the basis of these data, and its known role in trafficking proteins to the plasma membrane,14–17 we proposed that Sec10 and the exocyst are required to build primary cilia by targeting and docking vesicles carrying ciliary proteins.

A possible mechanism to target the exocyst to nascent primary cilia, so it can participate in ciliogenesis, is through the Par complex. We previously showed that the exocyst co-localizes with Par312 and directly interacts with Par6,18 both components of the Par complex, which also includes atypical PKC. Cdc42 is associated with the Par complex.19,20 In addition to their well studied function at cell-cell contacts, the Par complex has been immunolocalized to primary cilia and is necessary for ciliogenesis.21,22 The exocyst is regulated by multiple Rho and Rab family GTPases (reviewed by Lipschutz and Mostov9), including Cdc42, which regulates polarized exocytosis via interactions with the exocyst in yeast.23 Using inducible MDCK cell lines that express constitutively active or dominant negative forms of Cdc42,24,25 we established that Cdc42 is centrally involved in three-dimensional collagen gel cystogenesis and tubulogenesis.26 Whether and how Cdc42 might participate in ciliogenesis and cooperate with the exocyst in ciliary membrane trafficking are open questions.

Toward this end, we showed, in cell culture, that Cdc42 co-immunoprecipitated and co-localized with Sec10 and that Cdc42 was necessary for ciliogenesis in renal tubule cells, in that Cdc42-dominant negative expression, small hairpin RNA knockdown of Cdc42, and small hairpin RNA knockdown of Tuba, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Cdc42, all inhibited ciliogenesis. Exocyst Sec8 and polycystin-2 also no longer localized to the primary cilium, or the ciliary region, after Cdc42 and Tuba knockdown.18 As noted, we showed that Sec10 directly binds to Par6, and others have shown that Cdc42 also directly binds to Par6.27,28 Knockdown of both Sec1029 and Cdc42 increased mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation.18

Here, using two different living organisms, we confirm and extend our in vitro findings. We show that cdc42 knockdown in zebrafish phenocopies many aspects of sec10 and pkd2 knockdown—including curved tail, glomerular expansion, and MAPK activation—suggesting, in conjunction with our previous data,12,18,29 that cdc42 may be required for sec10 (and possibly pkd2) function in vivo. Other ciliary phenotypes include hydrocephalus and loss of photoreceptor cilia. We also demonstrate a synergistic genetic interaction between zebrafish cdc42 and sec10 for these cilia-related phenotypes, indicating that cdc42 and sec10 function in the same pathway. Demonstrating that the phenotypes were not due to off-target effects from the cdc42 MOs, we rescued the phenotypes with mouse Cdc42 mRNA. Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice died of kidney failure within weeks of birth; histologic examination revealed cystogenesis in distal tubules and collecting ducts and decreased ciliogenesis in cyst cells. Cdc42 conditional knockout kidneys showed increased tubular epithelial cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, increased interstitial fibrosis, and MAPK pathway activation, all features of the nephronophthisis form of PKD. These data, along with our previously published results, support a model in which Cdc42 localizes the exocyst to the primary cilium, whereupon the exocyst then targets and docks vesicles carrying proteins necessary for ciliogenesis; if this does not occur, the result is abnormal ciliogenesis and PKD.

Results

cdc42 Is Necessary for Zebrafish Kidney Development

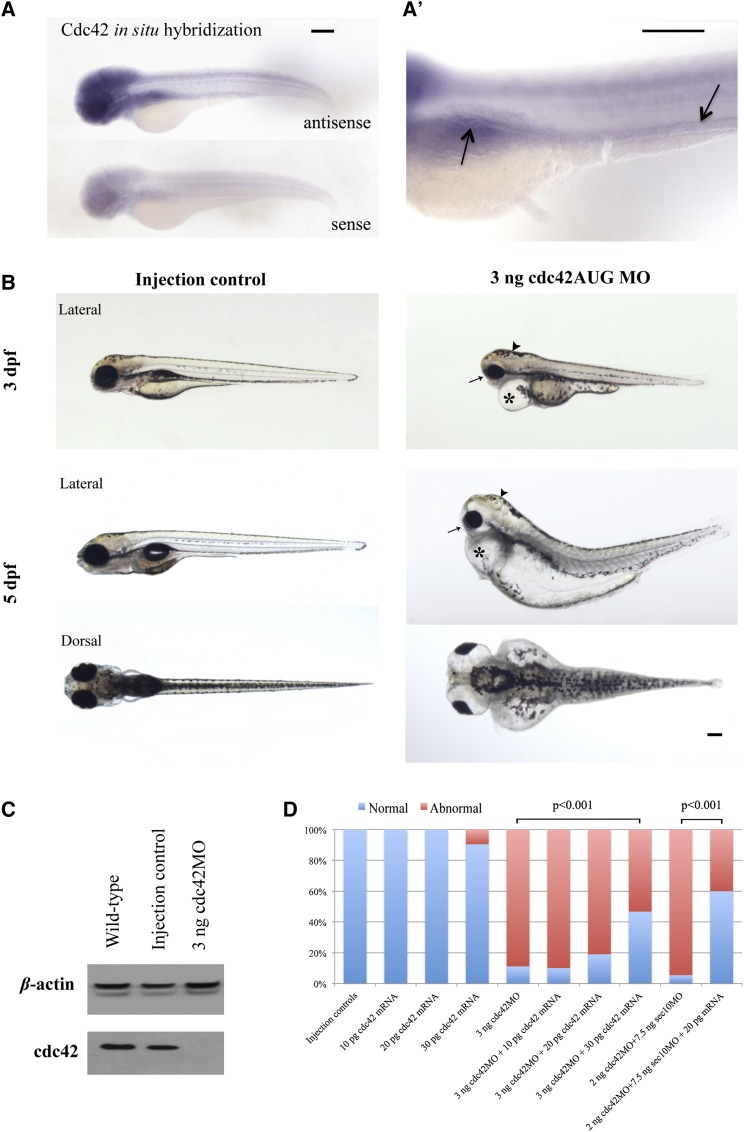

To determine whether cdc42 might have a role in zebrafish kidney development, we first needed to demonstrate that cdc42 localized to the kidney. We therefore performed whole mount in situ hybridization of zebrafish embryos at 3 days postfertilization (dpf) using antisense (Figure 1A, upper section) and sense (Figure 1A, lower section) probes, which showed that cdc42 is expressed in the pronephric kidney, eye, and brain of wild-type zebrafish embryos (Figure 1, A and A').

Figure 1.

cdc42 expression occurs in the zebrafish kidney, eye, and brain, and cdc42 knockdown by antisense MOs results in abnormal phenotypes. (A) Lateral views of whole mount in situ hybridization of zebrafish embryos at 3 dpf with antisense (upper part) and sense probes (lower part). cdc42 is expressed in kidney, eye, and brain. (A’) Higher magnification image of the pronephric kidney and tubule highlights cdc42 expression in this region (arrows). (B) Phenotype of injection control (with phenol red) embryos and cdc42 morphants (MO) at 3 dpf and 5 dpf. Defects in cdc42 morphants include smaller eyes (arrow), hydrocephalus (arrowhead), pericardial edema (*), and a short curved tail. (C) cdc42 protein at 3 dpf was undetectable by Western blot in 3 ng cdc42AUG MO embryos. Bar, 200 μm. (D) The cdc42AUG MO embryos were rescued by co-injecting mouse mRNA, which is resistant to the cdc42AUG MOs, due to a difference in primary base pair structure. The highly significant rescue with mouse Cdc42 mRNA shows that the ciliary phenotypes seen in the cdc42AUG MO embryos are not due to off-target effects.

After localization of cdc42 to the zebrafish kidney, we then used MOs to knock down zebrafish Cdc42 levels. Per the Zebrafish Model Organism Database (ZFIN), there are three zebrafish isoforms of human Cdc42: isoform A (NP_956926), which is 98% identical; isoform B (NP_001035012), which is 77% identical; and isoform C (NP_956159), which is 91% identical. We chose to knock down Cdc42 isoform A, the most identical, with an antisense start-site MO, which targets both maternal and zygotic transcripts. Injection of 3 ng of the start-site MO against zebrafish cdc42 isoform A (hereafter called “cdc42AUG MO”) into one-cell–staged embryos, compared with the injection control of phenol red only (Figure 1B, left section), revealed multiple defects at 3 dpf and 5 dpf that were consistent with ciliary defects, including hydrocephalus, small eyes, pericardial edema, and a short curved tail (Figure 1B, right section). These phenotypic defects are consistent with the cdc42 expression pattern we found by in situ hybridization (Figure 1A).

A typical injection trial of 3 ng cdc42AUG MO resulted in the following phenotypes: 11% wild-type; 28% with edema only; 13% with edema and small eyes; and 48% with edema, small eyes, and hydrocephalus (n=63). In comparison, injection controls showed no abnormal phenotypes (n=73). In all the trials combined, the number of abnormal embryos after injection of 3 ng of the cdc42AUG MO, compared with controls, was highly statistically significant at P<0.001. Supplemental Table 1 lists all the zebrafish experiments and statistical analyses (n=1877). Cdc42 protein at 3 dpf was undetectable by Western blot in the cdc42 morphant embryos (Figure 1C), indicating that this cdc42 MO effectively knocked down cdc42. Importantly, we rescued the phenotypes with mouse Cdc42 mRNA, which is resistant to the cdc42AUG MO because of differences in primary base pair structure, thereby demonstrating that the phenotypes were not due to off-target effects of the cdc42 MOs (Figure 1D).

cdc42 Morphants Have Ciliary Defects

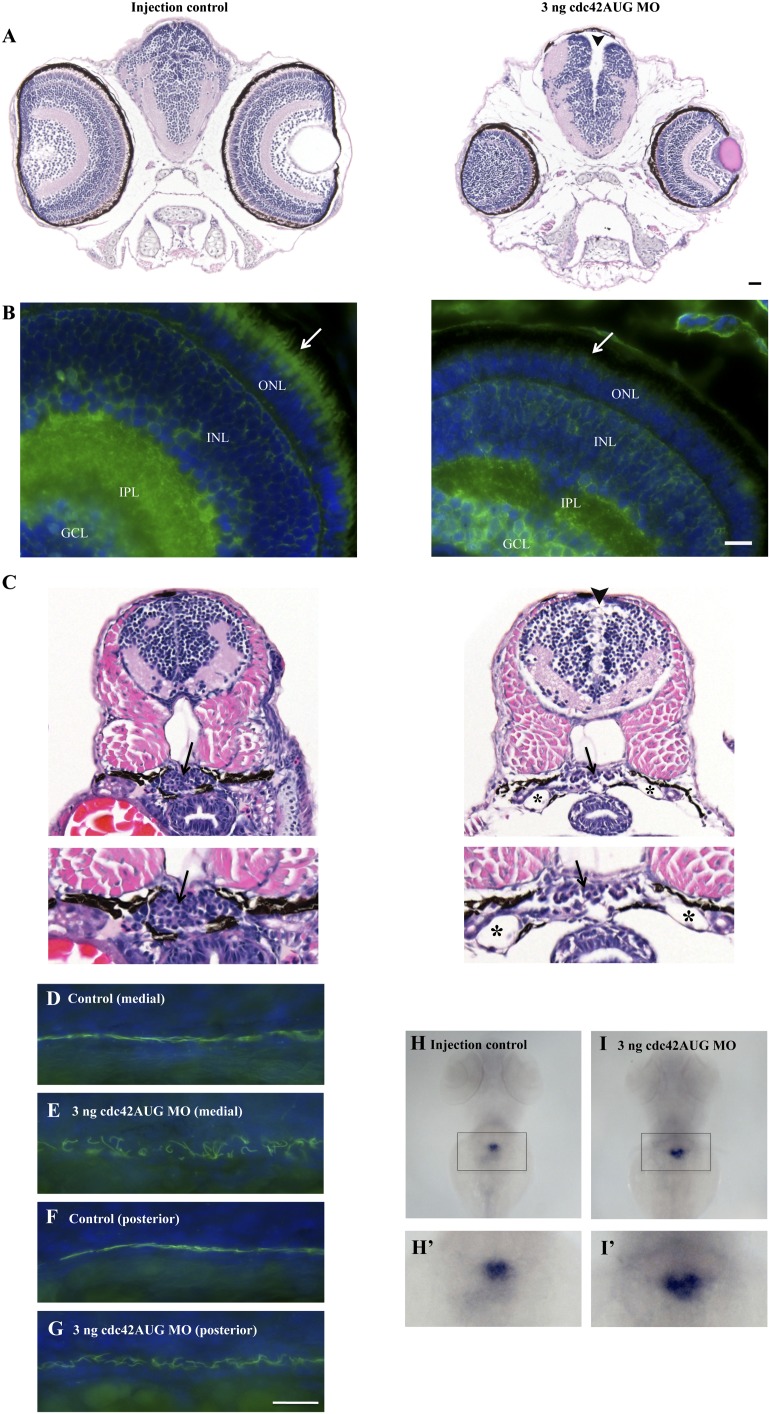

We next investigated the morphant phenotypes seen in Figure 1 in more detail by histologic and immunofluorescence studies. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of fixed sections showed defects in the eye (specifically, loss of the outer segments of the photoreceptor cells) and hydrocephalus, an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the ventricles of the brain (arrowhead in Figure 2A). In the eye, the outer segment of the photoreceptor cell, which is a modified cilium,30 was clearly absent when probed using antibody against acetylated α-tubulin, which stains primary cilia. The cilia in the cells surrounding the dilated ventricles appeared intact, although their function was not tested (not shown). We next examined the pronephric kidneys. The morphologic features of the glomeruli were abnormal. Instead of the normal compact U-shaped glomerulus, glomeruli from cdc42AUG MO embryos showed disorganization and expansion (Figure 2C, arrow). The renal tubules were also clearly dilated (asterisk in Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

cdc42AUG MO embryos show abnormal ciliary development. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of fixed sections shows defects in the eye and hydrocephalus (arrowhead). (B) In the eye, the outer segment of the photoreceptor cell, which is a modified cilium, is absent (compare arrows in control, left, versus cdc42AUG MO embryos, right). Cilia are shown in green after staining with antibodies against acetylated α-tubulin. GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer where photoreceptor cells are found. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of fixed sections shows a normal compact U-shaped glomerulus in the controls on the left, with cdc42AUG MO embryos displaying disorganization and expansion of the glomerulus (arrows). The renal tubules are also dilated in the cdc42AUG MO embryos (*). (D–G) Medial and posterior pronephric duct cilia visualized with antiacetylated α-tubulin antibody (green) at 27 hours postfertilization. Compared with cilia in injection controls, mutant cilia are disordered. (H–I’) In situ hybridization for the early kidney marker wt1a (with enlarged insets), 3 dpf, dorsal view ×16 magnification. An uninjected embryo with condensed glomerular stain (H and H’) is shown, along with a 3 ng cdc42AUG MO embryo with expansion of the wt1-stained area (I and I’). The increase in glomerular size in the cdc42AUG MO versus control embryos was significant at P<0.0001. Bar, 10 μm for all images.

Given the ciliogenesis defects observed with cdc42 knockdown in vitro18 and in the eyes of cdc42AUG MO embryos (Figure 2, A and B), we predicted that pronephric cilia would be shorter or absent in the kidneys of the cdc42AUG MO embryos. Somewhat surprisingly, pronephric cilia at 27 hours postfertilization appeared of normal length in cdc42AUG MO embryos by immunofluorescence (Figure 2, D–G); however, the cilia were disordered within the medial (and to a lesser degree the posterior) pronephros, where dilations and pronephric cysts have been observed in other zebrafish cilia mutants.6,31 The discrepancy in pronephric ciliogenesis phenotypes between Cdc42 knockdown in vitro and in vivo may be explained by the presence of cdc42 isoforms B and C, although these isoforms were not detected by our antibody (Figure 1C). The disorganized cilia were similar to what we observed in sec10 and pkd2 morphants.29

Also similar to sec10 and pkd2 morphant embryos,3 cdc42AUG MO embryos showed glomerular expansion in the pronephros by in situ hybridization with the glomerular marker, Wilms tumor 1a (wt1a) at 3 dpf. Wild-type embryos showed a condensed glomerular stain (Figure 2, H and H', 100% condensed; n=30), whereas cdc42AUG MO embryos showed an enlarged stain (Figure 2, I and I'; 18 of 19 embryos with enlarged stain). This difference was highly significant at P<0.0001.

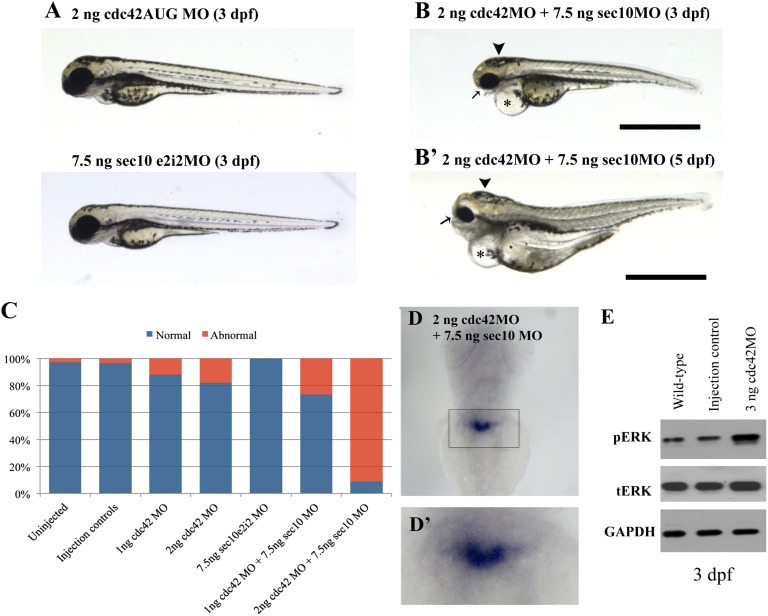

sec10 and cdc42 Genetically Interact for Cilia-Related Phenotypes

Our in vitro12,18 and in vivo29 analyses together support a link between exocyst sec10 and cdc42. The curved tail, hydrocephalus, small eyes, edema, and wt1a expansion phenotypes shared between sec10MO and cdc42MO embryos have also been observed upon knockdown of other ciliary proteins.32,33 We therefore wanted to directly test for a specific genetic interaction between these two genes. We titrated both sec10 and cdc42 MOs to find suboptimal doses that did not result in strong gross phenotypes on their own. Interestingly, when we co-injected both MOs at these reduced doses, we observed a striking synergistic effect. Co-injection of 2 ng cdc42MO plus 7.5 ng sec10MO yielded curved tail up, hydrocephalus, small eyes, edema, and wt1a expansion phenotypes, while each MO alone produced mostly wild-type phenotypes. Seven separate trials were performed and a total of 1454 embryos were examined. The addition of 7.5 ng sec10MO to 2 ng of cdc42MO resulted in a greater proportion of abnormal phenotypes than expected based on the results of single-agent experiments (P<0.001), thereby demonstrating genetic synergy (Figure 3, A–D). The addition of 7.5 ng sec10MO to 1 ng of cdc42MO also resulted in a synergistic effect, although the effects were less dramatic (P<0.001 compared with uninjected controls, and P=0.058 when compared with 1 ng of cdc42MO alone). The genetic interaction we observed between sec10 and cdc42 MOs suggests that cdc42 plays a role in sec10 function in multiple cilia-related processes. Similar to our previous in vitro findings in Cdc42 knockdown cells,18 by Western blot we also found increased levels of phosphorylated (active) ERK (pERK) in most cdc42AUG MO embryos (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

cdc42 and sec10 genetically interact. A synergistic interaction resulting in hydrocephalus (arrowhead), small eyes (arrow), pericardial edema (*), and tail defects was observed upon co-injection of suboptimal doses of 2 ng cdc42MO plus 7.5 ng sec10MO (B and B’). Injection of these amounts of these MOs alone did not generally result in an abnormal phenotype (A). Bar, 1 mm. (C) Histograms show the quantification of the effect of MOs at 3 dpf. Co-injection of suboptimal doses of 2 ng cdc42MO and 7.5 ng sec10MO resulted in an increased abnormal phenotype. Seven separate trials were performed and a total of 1,454 embryos examined. The synergistic effect of adding 7.5 ng sec10MO to the 2 ng of cdc42MO was significant at P<0.001. (D and D’) Expansion of the wt1-stained area is seen in the 2 ng cdc42MO plus 7.5 ng sec10MO embryo and is similar to the expansion seen in the 3 ng cdc42MO (compare Figure 3, D and D’, with Figure 2, I and I’). (E) Increased pERK levels were detected in 3 ng cdc42MO embryos. Lysates were generated from 10 embryos in each condition. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; tERK, total ERK.

Generation of Cdc42 Kidney-Specific Knockout Mice

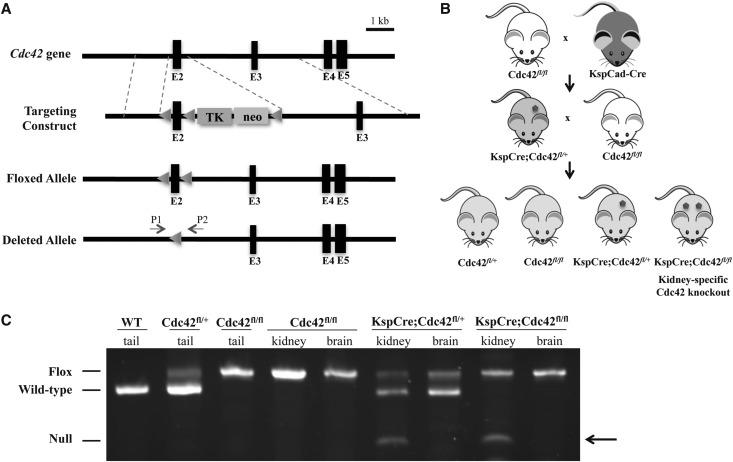

Zebrafish have pronephric kidneys and mammals have more complex metanephric kidneys. To determine the role of Cdc42 in metanephrogenesis, we decided to knock out Cdc42 in mice. Global knockout of Cdc42 resulted in early embryonic lethality, so we needed to generate a kidney-specific Cdc42 knockout mouse. Dr. Brakebusch generously allowed us to use his Cdc42fl/fl mice. Cdc42fl/fl mice34 and the targeting scheme are shown in Figure 4A.

Figure 4.

Kidney tubule cell-specific Cdc42 knockout mice were successfully generated. (A) Targeting scheme showing the Cdc42 gene (wild type), the targeting construct, and the conditional allele after homologous recombination of the targeting construct and removal of the floxed neo-TK cassette by transient Cre transfection.34 Loxp sites were inserted around exon 2 (containing the ATG start site). Features in the generation of the deleted allele include: exons (filled boxes); thymidine kinase expression cassette (TK); neomycin resistance expression cassette (neo); loxp sites (triangles); and primers for genotyping (P1 and P2). (B) The breeding strategy for generating Cdc42 kidney tubule cell-specific knockout mice, by crossing and then backcrossing KspCadherin-Cre/+ (KspCre) and Cdc42fl/fl mice, is shown. (C) The PCR products obtained after amplification of DNA from tails, kidneys, and brains clearly show the four possible genotypes illustrated in B. The lanes with PCR products from kidneys and brains of Cdc42fl/fl, KspCre;Cdc42fl/+, and KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl littermates show the recombined/null allele in the kidney but not the brain (arrow).

To knock out Cdc42 specifically in the kidney, we used a kidney tubule cell-specific Cre mouse line, KspCadherin-Cre (KspCad-Cre), which has been previously used to generate kidney tubule cell-specific mutants of ciliary proteins.35 The breeding strategy is shown in Figure 4B. All four possible genotypes were readily and reproducibly determined using a PCR-based genotyping strategy (Figure 4C).

Kidney-Specific Knockout of Cdc42 Leads to Early Postnatal Death

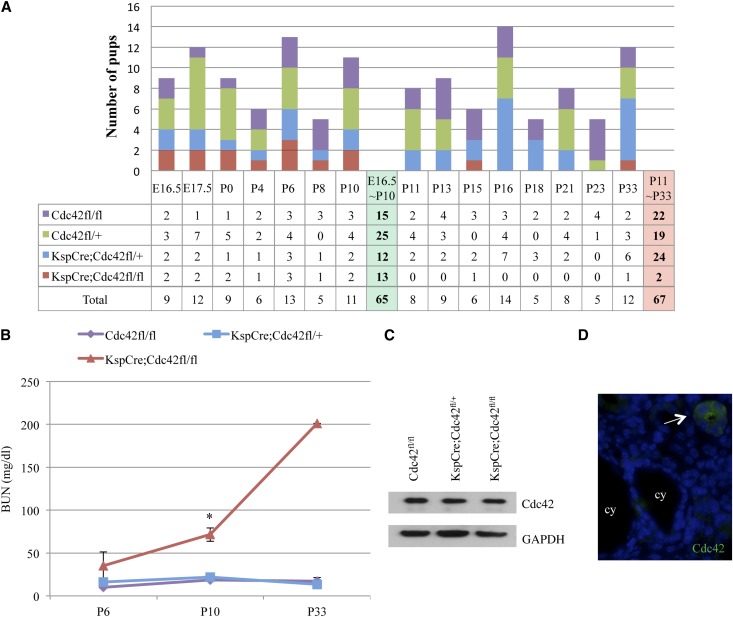

KspCre;Cdc42fl/+ mice were backcrossed to Cdc42fl/fl mice as described in Figure 4B. Of 65 pups tested at E16.5 to P10, there were 15 Cdc42fl/fl, 25 Cdc42fl/+, 12 KspCre;Cdc42fl/+, and 13 KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl mice. The moderate decrease in heterozygous and homozygous Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice from the expected 25% Mendelian ratios, suggests that kidney-specific loss of Cdc42 might be deleterious, even at this early age. The examination of 67 pups tested from P11 to P33 confirmed the lethality for the homozygous kidney-specific Cdc42 knockout mice, but not for the heterozygous kidney-specific Cdc42 knockout mice. There were 22 Cdc42fl/fl, 19 Cdc42fl/+, and 24 KspCre;Cdc42fl/+ mice, with 1 dead (mostly eaten) homozygous Cdc42 knockout (KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl) mouse found at P15, and 1 long-surviving homozygous Cdc42 knockout (KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl) mouse that was euthanized at P33 because of failure to thrive, growth restriction, and renal failure (BUN, 201 mg/dl) (Figure 5A). The paucity of kidney-specific Cdc42 knockout mice (KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl) mice after P10, compared with the expected 25% Mendelian ratio, indicates that lack of Cdc42 in the kidneys leads to an early postnatal death. The cause of death in the homozygous kidney-specific Cdc42 knockout mice is almost certainly renal failure, given significant elevations in BUN (Figure 5B). By Western blot of whole kidney lysates, we did not see a significant decrease in Cdc42 in the KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl mice (Figure 5C), which we attribute to the limited expression of KspCad-Cre in a subset of renal tubule cells (i.e., most of the cells in the kidneys of KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl mice express normal amounts of Cdc42).35–38 Supporting this interpretation, by immunofluorescence we saw an absence of Cdc42 in cysts in KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl mice, while normal-appearing tubules had Cdc42 present (Figure 5D). Interestingly, the enhanced expression of Cdc42 on the apical surface of the normal-appearing tubules corresponds to the localization that we18 and others39 have shown in cell culture.

Figure 5.

Lack of Cdc42 in kidney tubule cells leads to an early postnatal death. KspCre;Cdc42fl/+ mice were mated to Cdc42fl/fl mice as illustrated in Figure 4B. Of 65 pups tested from E16.5 to P10, there were 15 Cdc42fl/fl, 25 Cdc42fl/+, 12 KspCre;Cdc42fl/+, and 13 KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl mice. Of 67 pups tested from P11-P33, there were 22 Cdc42fl/fl, 19 Cdc42fl/+, and 24 KspCre;Cdc42fl/+ mice, with 1 dead (mostly eaten) homozygous Cdc42 knockout (KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl) mouse found at P15 and 1 long-surviving homozygous Cdc42 knockout (KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl) mouse that was euthanized at P33 because of failure to thrive, growth restriction, and renal failure. (B) By linear regression modeling, BUN levels in Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice were significantly higher than in littermate control KspCre;Cdc42fl/+ and Cdc42fl/fl mice at P10 (P=0.04). (C) Western blot showed no significant difference between levels of Cdc42 from whole kidney lysate in the different genotypes, although it should be noted that we are knocking out Cdc42 only in a small subset of kidney cells. (D) By immunofluorescence, Cdc42 is not seen in the cysts (cy) but is seen in the normal-appearing tubules of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (arrow). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Kidney-Specific Knockout of Cdc42 Results in Cysts in the Distal Tubules and Collecting Ducts

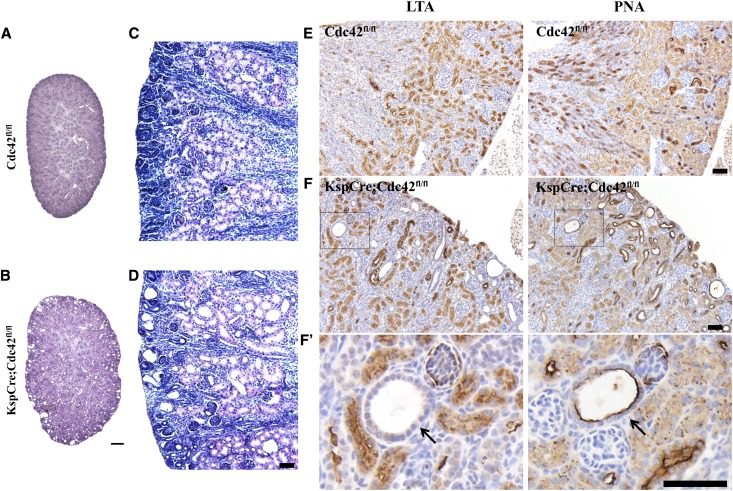

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections from the kidneys of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice at P4 and P6 show many small cysts (Figure 6, A–D) that localize to the distal tubule and collecting ducts, as determined by negative staining of cyst cells with lotus tetragonolobus agglutinin lectin, a lectin specific for proximal tubule cells, and positive staining of cyst cells with peanut agglutinin lectin (PNA), a lectin specific for distal tubule and collecting-duct cells (Figure 6, E and F). The localization of the cysts is consistent with the fact that KspCad-Cre is 100% penetrant in these tubule segments.35,38

Figure 6.

KspCre;Cdc42fl/fl mice develop renal cysts in the distal and collecting tubules. (A–D) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of kidneys from control (A and C) and Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (B and D) at P4 (A and B) and P6 (C and D). (E) Section of a control kidney incubated with LTA lectin, which stains the apical membrane of proximal tubule epithelial cells (brown color), and PNA lectin, which stains distal tubule and collecting tubule cells. (F and F’) Section of a Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout kidney incubated with LTA lectin shows no staining of cysts (arrow in expanded inset to left), while a section incubated with PNA lectin shows staining of cysts (arrow in expanded inset to right), indicating that the cysts arise from distal tubules and collecting ducts. Bar for A and B, 200 μm. Bar for C–F, 20 μm.

Ciliogenesis Is Inhibited in Cdc42 Kidney-Specific Knockout Mice

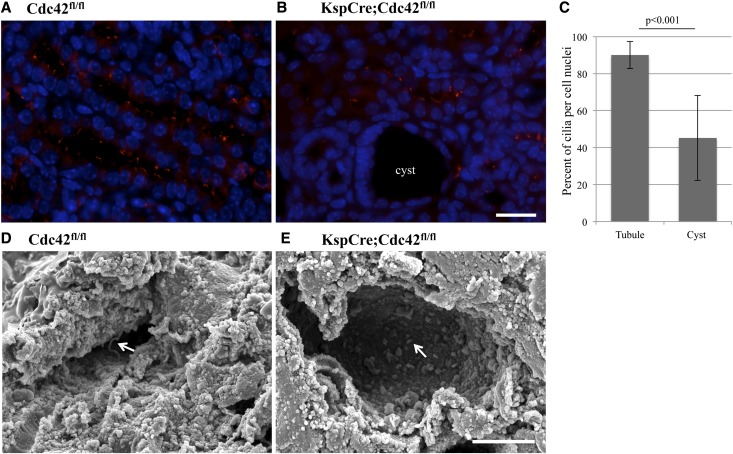

Given the ciliary phenotypes in cdc42AUG MO embryos (Figures 1–3), our data showing knockdown of Cdc42 in cell culture inhibits ciliogenesis,18 and the fact that knockout of many ciliary proteins in mice leads to a polycystic phenotype,2 we next investigated ciliogenesis in Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice. Immunostaining of kidney sections from control mice (Figure 7A) and Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (Figure 7B) at P4 show a significant lack of cilia in the cystic areas of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice but normal amounts of cilia in the unaffected tubules from these mice (Figure 7C). Scanning electron microscopy of kidneys from control (Figure 7D) and Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (Figure 7E) at P6 also shows impaired ciliogenesis in the Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice. Cdc42 is involved in multiple cellular processes, such as polarity. In support of the idea that the phenotype here is mainly due to the effect of Cdc42 acting at the primary cilium in the cells surrounding cysts in the Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice, cell polarity appeared to be largely preserved, at least with respect to basolateral E-cadherin and apical gp135 localization (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 7.

Primary ciliogenesis is inhibited in the cysts of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice. (A and B) Immunostaining of acetylated α-tubulin (red) in kidneys from control (A) and Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (B) at P4, shows lack of cilia in cells surrounding cysts. (C) Quantification from kidney tubule cell-specific Cdc42 knockout mice shows a significant decrease in the number of cilia seen per cell in cysts (which presumably are deficient in Cdc42 because no cysts were seen in control mice) compared with normal-appearing tubules, which most likely express Cdc42. Error Bars represent standard deviation and were calculated by Excel. (D) Scanning electron microscopy of kidneys from control (D, arrow) and Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (E, arrow) at P6 shows abnormal-appearing, short, stubby cilia in cells surrounding cysts. Bar, 20 μm.

Increased Proliferation, Apoptosis, and Fibrosis in Cdc42 Kidney-Specific Knockout Mice

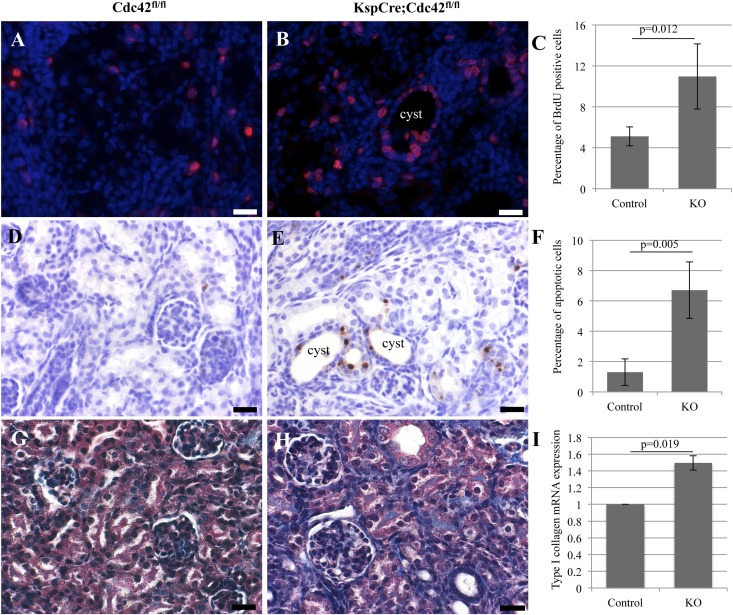

In many forms of PKD, especially nephronophthisis, levels of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and fibrosis are increased.40 To investigate this, we first examined bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation, a marker of active cell division, in sections of kidneys from the Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice and wild-type littermate controls, and found it to be significantly increased in the Cdc42 conditional knockout kidneys (Figure 8, A–C). We next examined apoptosis, using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining, and found it to be increased as well in Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (Figure 8, D–F). Finally, we investigated fibrosis, using Masson trichrome staining, and it too was increased in the kidneys of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (Figure 8, G and H). As a marker of increased fibrosis, we examined mRNA levels of collagen I and found them to be significantly increased in the kidneys of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (Figure 8I).

Figure 8.

Increase in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and fibrosis in kidneys of Cdc42 conditional knockout mice. (A and B) BrdU incorporation, a marker of active cell division, is significantly increased in sections of kidneys from the Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (KO) compared with wild-type littermate controls. Bar, 10 μm. Quantification is shown in C. (D and E) Apoptosis, using TUNEL, was significantly increased in Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice compared with wild-type littermate controls. Quantification is shown in F. (G and H) Fibrosis, using Masson trichrome staining, was increased in the kidneys of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice compared with controls. As a marker of increased fibrosis, we examined mRNA levels of collagen I and found them significantly increased in the kidneys of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice (I). Bar, 10 μm. Error Bars in C, F, and I represent standard deviation and were calculated by Excel.

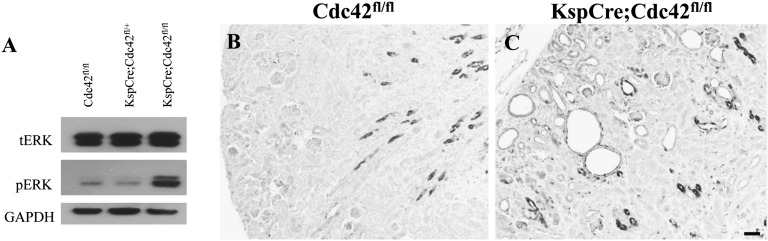

MAPK Pathway Activation Occurs in Cdc42 Kidney-Specific Knockout Mice

Finally, we examined a downstream signaling pathway, MAPK, that has been shown to be causally involved in PKD in the pcy nephronophthisis model.41 MAPK activation, specifically phosphorylation of the final protein ERK (pERK) in this pathway, was found to be significantly elevated by Western blot in three of five mice examined (Figure 9A). Importantly, in tissue sections, by immunohistochemistry, pERK was increased in kidney cyst cells in all five Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice examined (Figure 9B and Supplemental Figure 2). The fact that some cysts in the kidneys of these mice displayed minimal, or no, pERK activation (Supplemental Figure 2) suggests that other signaling pathways (e.g., the planar cell polarity pathway,42 given the dilated tubules and disordered cilia seen in the cdc42AUG MO kidneys) might also be activated after Cdc42 knockout in kidney tubule cells.

Figure 9.

Active pERK is increased in the kidneys of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice. (A) Immunoblot analysis of proteins extracted from the whole kidneys of P6 control and Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice, showed increased pERK levels in Cdc42 knockout mice. Blots were probed with antibodies against total ERK (tERK), active pERK, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). (B and C) Immunohistochemistry with antibodies against pERK showed increased pERK in the kidneys of Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice at P8, especially in the cells surrounding cysts. Bar, 20 μm.

Discussion

A major strength of this study is that we used two different animal models, zebrafish and mouse, each of which has specific advantages that could be exploited to investigate the role of Cdc42 in renal ciliogenesis, cystogenesis, and regulation of the exocyst.

Zebrafish is a very useful animal model owing to the feasibility of studying genetic interactions, the ability to use antisense MOs for knockdown, the opportunity to quickly assay large numbers of embryos, and the ease of viewing organ phenotypes in living larvae.4 For these reasons, we initiated our Cdc42 studies in zebrafish.

We previously showed, in cell culture, that Cdc42 biochemically interacted with exocyst Sec10, co-localized with the exocyst at primary cilia, and that knockdown of Cdc42 and Tuba, a Cdc42 GEF, inhibited ciliogenesis and resulted in MAPK pathway activation.18 We show here that cdc42 knockdown in zebrafish phenocopies many aspects of sec10 (and pkd2) knockdown, including tail curvature, glomerular expansion, and MAPK activation. Other ciliary phenotypes include hydrocephalus and loss of photoreceptor cell cilia. Indeed, we show ciliary mutant phenotypes in all the tissues (brain, eye, and kidney) in which cdc42 was highly expressed by in situ hybridization.

Using MOs to knock down cdc42 levels in vivo in zebrafish, we observe an absence of photoreceptor cell cilia, specifically the outer segments, in cdc42AUG MO embryos. We also saw hydrocephalus in cdc42AUG MO embryos, which can be due to defects in ependymal cell cilia in the ventricles of the brain.43 Although the absence of gross morphologic defects in pronephros cilia, and in cells surrounding the dilated ventricles of the brain, was initially surprising, it is possible that other isoforms of Cdc42—which are unaffected by our start-site MO—are sufficient to allow for cilia assembly in the kidney. Per the Zebrafish Model Organism Database, there are three zebrafish isoforms of human Cdc42, including isoform A (NP_956926), which is 98% identical, and is the sequence we used to generate the MO described here. Future studies will investigate the expression pattern of Cdc42 isoforms B and C, which might, for example, show expression in the kidney and in cells surrounding the ventricles of the brain, but not the eye. Nevertheless, these other isoforms were unable to restore complete pronephric cilia function during zebrafish development because cdc42 isoform A MO embryos still showed kidney cilia-related phenotypes that have been observed in other cilia mutants in zebrafish—such as edema, disordered cilia, and glomerular expansion. Therefore, we believe that the knockdown of the Cdc42 isoform most related to mammalian Cdc42, with a start-site MO, allowed us to uncover a role for cdc42 in pronephric cilia function. Maternal-zygotic cdc42 mutants of all three different isoforms, which could well result in early embryonic lethality, would likely be required to definitively say whether cdc42 is required for pronephric cilia formation in zebrafish. The inhibition of ciliogenesis that was seen in the cells surrounding cysts in Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice confirm the importance of Cdc42 for renal tubule cell cilia formation, and highlights the advantages of using multiple animal models to investigate these processes. Together with our previous work,18 our studies in zebrafish and mice demonstrate that Cdc42 is likely to be important for both kidney cilia formation and function.

We next took advantage of the robust ability to study genetic interactions in zebrafish. Using small amounts of cdc42 and sec10 MOs that alone generally had no effect, injection of both together resulted in a synergistic genetic interaction between cdc42 and sec10 for many of the cilia-related phenotypes. This suggests that cdc42 and sec10 act in the same pathway. We previously proposed that Sec10 and the exocyst are important for transporting proteins necessary for ciliary structure.12 Given that Cdc42 regulates the exocyst in yeast,23 we propose a model whereby Cdc42 is necessary for exocyst action at the primary cilium. If Cdc42 is required to regulate the exocyst, then MO co-injection would further impair ciliary Sec10 levels beyond that seen after direct knockdown of Sec10 by a suboptimal dose of MO because a reduced amount of Sec10 would be present to act at the primary cilium.

Zebrafish have pronephric kidneys and mammals have metanephric kidneys; thus, we turned to mice to further investigate the role of Cdc42 in ciliogenesis and cystogenesis. Because global knockout of Cdc42 in mice results in early embryonic lethality, we used a floxed Cdc42 mouse created by the Brakebusch Group, and validated by that laboratory34,44 and others.45 We crossed these mice to kidney tubule cell-specific KspCad-Cre mice that had been successfully used to knock out other ciliary proteins, such as Kif3A,35 which also cause early embryonic lethality when knocked out globally.46,47 The phenotype in our Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice, especially the multiple small cysts, increased cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, and increased fibrosis, is more consistent with a nephronophthisis model40 than ADPKD, in which greatly enlarged cystic kidneys are seen.2 Although less common than ADPKD, nephronophthisis, a group of autosomal recessive disorders, is the most frequent genetic cause of ESRD up to the third decade of life.48 Indeed, a recent study investigating the utility of whole exome sequencing in improving diagnosis and altering patient management found a mutation in an exocyst component, Exo84, in a family with Joubert syndrome, a nephronophthisis-related disorder that also includes defects in brain (cerebellar) development. The p.E265G variant found in the family occurred in the B6 loop of the highly conserved pleckstrin homology domain, which is involved in binding phosphatidylinositol lipids for vesicular transport. This was the single, segregating variant in the family and was not present in 200 ethnically matched controls. It was predicted to be damaging by POLYPHEN-249,50 and occurred in a fully conserved residue.51 It should be noted, however, that we previously showed that polycystin-2, one of the two causative proteins in ADPKD, co-localized with the exocyst at the primary cilium18 and biochemically interacted with the exocyst.29 Cell proliferation is also a well known characteristic of ADPKD cells and plays a major role in the formation of the cysts that destroy the kidney, leading some to refer to ADPKD as “neoplasia in disguise.”52 Thus, involvement of Cdc42 and the exocyst in ADPKD is also quite possible.

Although we favor a model whereby the Cdc42 mutant phenotypes occur because of the central role of Cdc42 in ciliogenesis, we recognize the possibility that Cdc42 may play a different role because some proteins implicated in cilia function also have cilia-independent functions. Many ciliary proteins are not exclusively localized to the cilium, and it has recently been argued that polycystin function in the endoplasmic reticulum is more relevant for the observed curly tail phenotype in zebrafish morphants.53 Indeed, multiple IFT proteins have recently been shown to have important functions in nonciliated cells.54

A key question, given the widespread localization of Cdc42 over the apical surface of renal tubule epithelial cells observed by us18 and others,39 then becomes, How is Cdc42 activated so that it can regulate the exocyst during ciliogenesis? A likely explanation is that one or more localized GEFs produce Cdc42-GTP activity at or near the primary cilium. Tuba, a Cdc42 GEF, was shown to be concentrated subapically, where the primary cilium forms.55 Knockdown of Tuba, in our previous study, inhibited ciliogenesis, although not to the same degree as knockdown of Cdc42.18 This may be due to incomplete knockdown of Tuba in our MDCK cells, or, alternatively, there may be one or more other GEFs that activate Cdc42 at the primary cilium. In a recent screen for modulators of ciliogenesis, 7784 therapeutically relevant genes across the human genome were tested using high-throughput small interfering RNA (siRNA).56 In that screen, intersectin 2 (ITSN2), another Cdc42 GEF, was shown to be a positive regulator of ciliogenesis. Importantly, ITSN2 was recently localized to the centrosome/basal body, which is at the base of the primary cilium, in MDCK cells.57 In the high-throughput siRNA screen by Kim et al., Cdc42 was listed as a rejected gene, based on “siRNA toxicity,” and the effect of Cdc42 knockdown on ciliogenesis was, therefore, not determined.56

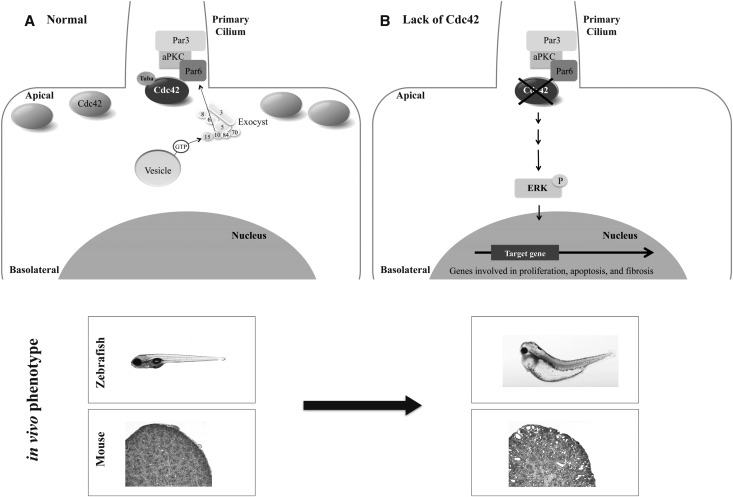

Together, these findings provide the basis for a model in which the exocyst complex is localized to the primary cilium by activated Cdc42, is stabilized at the primary cilium by binding to the Par complex through Par6,18 and then targets and docks vesicles carrying proteins necessary for ciliogenesis (Figure 10). Given the importance of the primary cilium to many “ciliopathies,” including PKD, identifying the mechanisms of ciliary assembly governed by the exocyst could reveal novel therapeutic targets.

Figure 10.

Model for the role of Cdc42 in delivery of ciliary proteins. (A) Our data support a model in which the exocyst complex is localized to the primary cilium by Cdc42, which is located all along the apical surface but is activated at the primary cilium by Tuba, a Cdc42 GEF. The exocyst is then stabilized by Sec10 binding directly to the Par complex via Par6. Once the exocyst complex is stabilized at the nascent primary cilium, it then targets and docks vesicles carrying ciliary proteins by interacting with a small GTPase, Rab8, found on vesicles. (B) When Cdc42 is lacking in a cell, the exocyst no longer localizes to primary cilia and increased cell proliferation, apoptosis, and fibrosis occurs, with the result being ciliary phenotypes (hydrocephalus, small eyes, tail curvature, and edema in zebrafish; PKD in mice).

Concise Methods

Ethics Statement

All zebrafish experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center. All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pennsylvania.

Zebrafish Injections, MO Knockdown, and Rescue

Embryos were injected at the one-to-four–cell stage, and MOs were diluted with phenol red tracer (P0290, Sigma) at 0.05% and injected at 500 pl or 1 nl per embryo. cdc42AUG and sec10e2i2 MOs, designed against zebrafish cdc42 and sec10, were purchased from Gene Tools, LLC: cdc42AUG-MO (5′-CAACGACGCACTTGATCGTCTGCAT-3′), sec10e2i2-MO (5′- AATATTCTGTAACTCACTTCTTAGG -3′). cdc42AUG-MO was designed to target the ATG start codon. sec10e2i2-MO was described previously.29 MOs were injected as single doses of 1, 2, or 3 ng cdc42-MO (designated in the text as cdc42AUG MO) or a combined dose of 1 or 2 ng cdc42AUG MO plus 7.5 ng sec10e2i2-MO (designated in the text as 1 or 2 ng cdc42AUG MO plus 7.5 ng sec10 MO) per embryo. Capped mouse Cdc42 full-length mRNA was synthesized using the mMessage mMachine T7 kit as instructed by the manufacturer (AM1344, Ambion). For the rescue experiments, 10–30 pg of Cdc42 mRNA was co-injected with the MOs into one-to-four–cell stage embryos.

Whole Mount In Situ Hybridization and Immunofluorescence in Zebrafish

Total RNA was isolated from 48 hpf zebrafish embryos using the RNAeasy Plus mini kit (74134, Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (4368814, Applied Biosystems) as described in the manual. To detect the cdc42 expression pattern in vivo, RNA probes were synthesized as previously described.58,59 The primer sequences for RNA probes are listed as follows (the T7 promoter sequence is highlighted in bold): Antisense (forward: 5′- GCGTCGTTGTTGGTGATGGTGC-3′, reverse: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGCCTTCAGATCGCGGGCCA-3′), sense (forward: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCGTCGTTGTTGGTGATGGTGC-3′, reverse: R: 5′-AGCCTTCAGATCGCGGGCCA-3′). DIG-labeled RNA probes were used for RNA in situ hybridization using standard methods.60 The wt1a probes were prepared as previously published.29 Immunofluorescence for cilia staining in zebrafish was performed similar to previously published protocols.61

Quantification of Glomerular Size

Glomerular width was measured with the Fiji (Image J) software, version 1.47g, on images of whole embryos collected using a Leica M205 C microscope and a DFC450 digital camera. Glomerular width was evaluated by collecting one image at the area of widest diameter from each mutant or wild-type embryo.

Histology

Zebrafish and mouse tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. After gradual dehydration into ethanol, tissues were embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4- to 5-μm thickness. Some of these sections were stained in hematoxylin and eosin.

Western Blot Analysis

Zebrafish embryo lysates were prepared with 3–5 dpf embryos as previously described.29 Mouse kidney lysates were homogenized in RIPA buffer (R0278, Sigma) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (P2714, Sigma) and phosphatase inhibitor (78420, Thermo), and the lysates were centrifuged at 13,500 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (23227, Thermo). The protein samples were separated on NuPage 4%–12% Bis-Tris gels (NP0336, Novex) and then transferred to a Nitrocellulose Membrane (LC2000, Novex).

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this study were mouse monoclonal anti-Cdc42 (610929, BD Transduction Laboratories), rabbit polyclonal anti–phospho-ERK1/2 (#9101, Cell Signaling), rabbit polyclonal anti-total ERK1(/2) (#9102, Cell Signaling), mouse monoclonal anti–glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G8795, Sigma), rabbit polyclonal anti-γ tubulin (T5192, Sigma), mouse monoclonal antiacetylated α-tubulin (T6793, Sigma), rat monoclonal anti-BrdU (ab6326, Abcam), mouse anti-GP135 (a gift from Dr. George Ojakian, State University of New York), rabbit anti–E-cadherin (ab15148, Abcam), biotinylated LTA (B-1325, Vector Laboratories), biotinylated PNA (B-1075, Vector Laboratories). Secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence (Cy2, Cy3) and Western blotting (horseradish peroxidase–conjugated) were from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories and Thermo Fisher Scientific, respectively.

Transgenic Mice and Genotyping

Cdc42fl/fl mice containing loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the Cdc42 gene were produced by homologous recombination, and Cdc42 organ-specific knockout mice were produced by deletion of exon 2 as described.34 A kidney tubule-restricted knockout for Cdc42 was generated by mating with KspCad-Cre transgenic mice. KspCad-Cre transgenic mice containing 1.3 kb of the Ksp-cadherin promoter linked to the coding region of Cre recombinase were produced as described,62 and were purchased from Jackson Labs. Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis of tail DNA. The primers used for Cre recombinase genotyping were as follows: 5′- GCAGATCTGGCTCTCCAAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGCAAATTTTGGTGTACGG-3′ (reverse). Cdc42fl/fl genotyping was carried out using the following primers: 5′-ATGTAGTGTCTGTCCATTGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCTGCCATCTACACATACAC -3′ (reverse).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out on a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR Systems (Applied Biosystems) sequence detection system. Primers used for type I collagen were as follows: forward, 5′-AATGGTGCTCCTGGTATTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTTCACCACTGTTGCCTTT-3′. The level of expression was normalized to that of β-actin (forward, 5′-ACCGTGAAAAGATGACCCAG-3′; reverse, 5′-AGCCTGGATGGCTACGTACA-3′).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence in Mice

For immunohistochemistry, the sections were deparaffinized and epitope retrieval was performed by heating the sections at 95°C in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH, 6.0) for 10 minutes. After being treated in 0.5% hydrogen peroxide for 5 minutes at room temperature, the sections were blocked by normal serum according to the instructions for the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit (PK-6101 and PK-6102, Vector Laboratories) and counterstained in hematoxylin. For the immunofluorescence staining, the 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed, rehydrated in graded ethanol, and retrieved with 10 mM sodium citrate (pH, 6.0). Sections were blocked in PBS containing 5% donkey serum and then incubated with antibodies.

Proliferation and Apoptosis Assays

Proliferation was assayed using BrdU incorporation. Two hours before harvesting of the kidneys, mice received intraperitoneal injections of 100 mg/kg body weight BrdU solution (B9285, Sigma-Aldrich). Apoptosis was determined using ApopTag Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (S7100, Chemicon) as directed by the manufacturer’s instructions. For BrdU and apoptosis (TUNEL) staining, positive nuclei were counted per high-power field (600×) in both control and knockout kidneys, and the percentage positivity was calculated per area.

BUN Analyses to Measure Kidney Function

Serum was prepared as described previously.63 Briefly, serum was separated from blood collected from the 6-, 10-, and 33-day-old mice and was stored at −80°C for further analysis. BUN levels were quantified from serum (analyzed by the Ryan Veterinary Hospital Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania).

Electron Microscopy

Kidneys from Cdc42 kidney-specific knockout mice and their littermate controls were bisected longitudinally after removal and were fixed in a solution containing 2% glutaraldehyde, 0.8% paraformaldehyde, and 0.1 M cacodylate. The fixed tissue was sectioned and rinsed with 100 mM of cacodylate buffer, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, washed with hexamethyldisilazane (Electron Microscopy Sciences), coated with platinum after air-drying for 5 minutes at 60°C, and analyzed on a scanning electron microscopy machine (XL20 SEM, Phillips Inc.).

Imaging

All images were captured in TIF format and processed in Adobe Photoshop CS5.1. For immunofluorescence, zebrafish embryos and mouse tissue were imaged on an Olympus BX42 and a Zeiss Axio Observer D1m. For histology and in situ hybridization, samples were imaged using a Leica M205C Light Microscope.

Statistical Analyses

Glomerular size was compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Phenotypes for the epistasis experiments were classified as abnormal, after MO injection, by the presence of any combination of the following features: edema, short body size, hydrocephalus, and small eyes. Logistic regression and chi-squared testing were used to compare the proportion of abnormal phenotypes across groups. Confidence intervals and P values were adjusted for within-trial correlation by clustering at the trial level, and robust SEM estimates were generated. These tests were performed using Stata software, v12.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). For comparison of means, a t test was performed using SPSS software (v.15.0) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). For all tests, P<0.05 was considered to represent statistically significant differences.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The University of Pennsylvania Biomedical Imaging Core Facility of the Cancer Center is acknowledged for providing imaging services, and the University of Pennsylvania Zebrafish Core, for providing essential services (such as maintenance and breeding of fish). Dr. Cord Brakebusch is gratefully acknowledged for allowing us to use his Cdc42fl/fl mice, and Drs. Jeffrey Hodgin and Matthias Kretzler for sending us these mice. Dr. Peter Reese is gratefully acknowledged for assistance with statistical analyses.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA Merit Award 1L01BX00820 to J.H.L.), National Institutes of Health (DK069909 and DK047757 to J.H.L., and DK093625 to L.H.), Satellite Healthcare (Norman S. Coplon Extramural Research Grant to J.H.L), a NephHope Postdoctoral Fellowship (to M.F.C.H.), and the University of Pennsylvania Translational Medicine Institute (pilot grant to J.H.L).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2012121236/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Webber WA, Lee J: Fine structure of mammalian renal cilia. Anat Rec 182: 339–343, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth BJ, Snyder R, Balkovetz DF, Lipschutz JH: Recent advances in the cell biology of polycystic kidney disease. Int Rev Cytol 231: 52–89, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisgrove BW, Snarr BS, Emrazian A, Yost HJ: Polaris and Polycystin-2 in dorsal forerunner cells and Kupffer’s vesicle are required for specification of the zebrafish left-right axis. Dev Biol 287: 274–288, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obara T, Mangos S, Liu Y, Zhao J, Wiessner S, Kramer-Zucker AG, Olale F, Schier AF, Drummond IA: Polycystin-2 immunolocalization and function in zebrafish. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2706–2718, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schottenfeld J, Sullivan-Brown J, Burdine RD: Zebrafish curly up encodes a Pkd2 ortholog that restricts left-side-specific expression of southpaw. Development 134: 1605–1615, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Z, Amsterdam A, Pazour GJ, Cole DG, Miller MS, Hopkins N: A genetic screen in zebrafish identifies cilia genes as a principal cause of cystic kidney. Development 131: 4085–4093, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emmer BT, Maric D, Engman DM: Molecular mechanisms of protein and lipid targeting to ciliary membranes. J Cell Sci 123: 529–536, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novick P, Field C, Schekman R: Identification of 23 complementation groups required for post-translational events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell 21: 205–215, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipschutz JH, Mostov KE: Exocytosis: The many masters of the exocyst. Curr Biol 12: R212–R214, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu SC, Ting AE, Hazuka CD, Davanger S, Kenny JW, Kee Y, Scheller RH: The mammalian brain rsec6/8 complex. Neuron 17: 1209–1219, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers KK, Wilson PD, Snyder RW, Zhang X, Guo W, Burrow CR, Lipschutz JH: The exocyst localizes to the primary cilium in MDCK cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 319: 138–143, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuo X, Guo W, Lipschutz JH: The exocyst protein Sec10 is necessary for primary ciliogenesis and cystogenesis in vitro. Mol Biol Cell 20: 2522–2529, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo W, Roth D, Walch-Solimena C, Novick P: The exocyst is an effector for Sec4p, targeting secretory vesicles to sites of exocytosis. EMBO J 18: 1071–1080, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grindstaff KK, Yeaman C, Anandasabapathy N, Hsu SC, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Scheller RH, Nelson WJ: Sec6/8 complex is recruited to cell-cell contacts and specifies transport vesicle delivery to the basal-lateral membrane in epithelial cells. Cell 93: 731–740, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipschutz JH, Guo W, O’Brien LE, Nguyen YH, Novick P, Mostov KE: Exocyst is involved in cystogenesis and tubulogenesis and acts by modulating synthesis and delivery of basolateral plasma membrane and secretory proteins. Mol Biol Cell 11: 4259–4275, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipschutz JH, Lingappa VR, Mostov KE: The exocyst affects protein synthesis by acting on the translocation machinery of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 278: 20954–20960, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moskalenko S, Henry DO, Rosse C, Mirey G, Camonis JH, White MA: The exocyst is a Ral effector complex. Nat Cell Biol 4: 66–72, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuo X, Fogelgren B, Lipschutz JH: The small GTPase Cdc42 is necessary for primary ciliogenesis in renal tubular epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 286: 22469–22477, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joberty G, Petersen C, Gao L, Macara IG: The cell-polarity protein Par6 links Par3 and atypical protein kinase C to Cdc42. Nat Cell Biol 2: 531–539, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin D, Edwards AS, Fawcett JP, Mbamalu G, Scott JD, Pawson T: A mammalian PAR-3-PAR-6 complex implicated in Cdc42/Rac1 and aPKC signalling and cell polarity. Nat Cell Biol 2: 540–547, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan S, Hurd TW, Liu CJ, Straight SW, Weimbs T, Hurd EA, Domino SE, Margolis B: Polarity proteins control ciliogenesis via kinesin motor interactions. Curr Biol 14: 1451–1461, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sfakianos J, Togawa A, Maday S, Hull M, Pypaert M, Cantley L, Toomre D, Mellman I: Par3 functions in the biogenesis of the primary cilium in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 179: 1133–1140, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Bi E, Novick P, Du L, Kozminski KG, Lipschutz JH, Guo W: Cdc42 interacts with the exocyst and regulates polarized secretion. J Biol Chem 276: 46745–46750, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jou TS, Nelson WJ: Effects of regulated expression of mutant RhoA and Rac1 small GTPases on the development of epithelial (MDCK) cell polarity. J Cell Biol 142: 85–100, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jou TS, Schneeberger EE, Nelson WJ: Structural and functional regulation of tight junctions by RhoA and Rac1 small GTPases. J Cell Biol 142: 101–115, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers KK, Jou TS, Guo W, Lipschutz JH: The Rho family of small GTPases is involved in epithelial cystogenesis and tubulogenesis. Kidney Int 63: 1632–1644, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atwood SX, Chabu C, Penkert RR, Doe CQ, Prehoda KE: Cdc42 acts downstream of Bazooka to regulate neuroblast polarity through Par-6 aPKC. J Cell Sci 120: 3200–3206, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamanaka T, Horikoshi Y, Suzuki A, Sugiyama Y, Kitamura K, Maniwa R, Nagai Y, Yamashita A, Hirose T, Ishikawa H, Ohno S: PAR-6 regulates aPKC activity in a novel way and mediates cell-cell contact-induced formation of the epithelial junctional complex. Genes Cells 6: 721–731, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fogelgren B, Lin SY, Zuo X, Jaffe KM, Park KM, Reichert RJ, Bell PD, Burdine RD, Lipschutz JH: The exocyst protein Sec10 interacts with Polycystin-2 and knockdown causes PKD-phenotypes. PLoS Genet 7: e1001361, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louvi A, Grove EA: Cilia in the CNS: The quiet organelle claims center stage. Neuron 69: 1046–1060, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan-Brown J, Schottenfeld J, Okabe N, Hostetter CL, Serluca FC, Thiberge SY, Burdine RD: Zebrafish mutations affecting cilia motility share similar cystic phenotypes and suggest a mechanism of cyst formation that differs from pkd2 morphants. Dev Biol 314: 261–275, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kramer-Zucker AG, Olale F, Haycraft CJ, Yoder BK, Schier AF, Drummond IA: Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer’s vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development 132: 1907–1921, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serluca FC, Xu B, Okabe N, Baker K, Lin SY, Sullivan-Brown J, Konieczkowski DJ, Jaffe KM, Bradner JM, Fishman MC, Burdine RD: Mutations in zebrafish leucine-rich repeat-containing six-like affect cilia motility and result in pronephric cysts, but have variable effects on left-right patterning. Development 136: 1621–1631, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu X, Quondamatteo F, Lefever T, Czuchra A, Meyer H, Chrostek A, Paus R, Langbein L, Brakebusch C: Cdc42 controls progenitor cell differentiation and beta-catenin turnover in skin. Genes Dev 20: 571–585, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin F, Hiesberger T, Cordes K, Sinclair AM, Goldstein LSB, Somlo S, Igarashi P: Kidney-specific inactivation of the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II inhibits renal ciliogenesis and produces polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 5286–5291, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Igarashi P: Following the expression of a kidney-specific gene from early development to adulthood. Nephron, Exp Nephrol 94: e1–e6, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Igarashi P, Shashikant CS, Thomson RB, Whyte DA, Liu-Chen S, Ruddle FH, Aronson PS: Ksp-cadherin gene promoter. II. Kidney-specific activity in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol 277: F599–F610, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karner CM, Chirumamilla R, Aoki S, Igarashi P, Wallingford JB, Carroll TJ: Wnt9b signaling regulates planar cell polarity and kidney tubule morphogenesis. Nat Genet 41: 793–799, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin-Belmonte F, Gassama A, Datta A, Yu W, Rescher U, Gerke V, Mostov K: PTEN-mediated apical segregation of phosphoinositides controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell 128: 383–397, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Attanasio M, Uhlenhaut NH, Sousa VH, O’Toole JF, Otto E, Anlag K, Klugmann C, Treier AC, Helou J, Sayer JA, Seelow D, Nürnberg G, Becker C, Chudley AE, Nürnberg P, Hildebrandt F, Treier M: Loss of GLIS2 causes nephronophthisis in humans and mice by increased apoptosis and fibrosis. Nat Genet 39: 1018–1024, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Omori S, Hida M, Fujita H, Takahashi H, Tanimura S, Kohno M, Awazu M: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibition slows disease progression in mice with polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1604–1614, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Menezes LF, Germino GG: Polycystic kidney disease, cilia, and planar polarity. Methods Cell Biol 94: 273–297, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banizs B, Pike MM, Millican CL, Ferguson WB, Komlosi P, Sheetz J, Bell PD, Schwiebert EM, Yoder BK: Dysfunctional cilia lead to altered ependyma and choroid plexus function, and result in the formation of hydrocephalus. Development 132: 5329–5339, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Czuchra A, Wu X, Meyer H, van Hengel J, Schroeder T, Geffers R, Rottner K, Brakebusch C: Cdc42 is not essential for filopodium formation, directed migration, cell polarization, and mitosis in fibroblastoid cells. Mol Biol Cell 16: 4473–4484, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott RP, Hawley SP, Ruston J, Du J, Brakebusch C, Jones N, Pawson T: Podocyte-specific loss of Cdc42 leads to congenital nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1149–1154, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marszalek JR, Ruiz-Lozano P, Roberts E, Chien KR, Goldstein LS: Situs inversus and embryonic ciliary morphogenesis defects in mouse mutants lacking the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 5043–5048, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeda S, Yonekawa Y, Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Nonaka S, Hirokawa N: Left-right asymmetry and kinesin superfamily protein KIF3A: New insights in determination of laterality and mesoderm induction by kif3A-/- mice analysis. J Cell Biol 145: 825–836, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf MT, Hildebrandt F: Nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol 26: 181–194, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR: A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 7: 248–249, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ng PC, Henikoff S: Accounting for human polymorphisms predicted to affect protein function. Genome Res 12: 436–446, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixon-Salazar TJ, Silhavy JL, Udpa N, Schroth J, Bielas S, Schaffer AE, Olvera J, Bafna V, Zaki MS, Abdel-Salam GH, Mansour LA, Selim L, Abdel-Hadi S, Marzouki N, Ben-Omran T, Al-Saana NA, Sonmez FM, Celep F, Azam M, Hill KJ, Collazo A, Fenstermaker AG, Novarino G, Akizu N, Garimella KV, Sougnez C, Russ C, Gabriel SB, Gleeson JG: Exome sequencing can improve diagnosis and alter patient management. Sci Transl Med 4: 138ra178, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Grantham JJ: Polycystic kidney disease: neoplasia in disguise. Am J Kidney Dis 15: 110–116, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu X, Wang Y, Schetle N, Gao H, Pütz M, von Gersdorff G, Walz G, Kramer-Zucker AG: The subcellular localization of TRPP2 modulates its function. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1342–1351, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finetti F, Paccani SR, Riparbelli MG, Giacomello E, Perinetti G, Pazour GJ, Rosenbaum JL, Baldari CT: Intraflagellar transport is required for polarized recycling of the TCR/CD3 complex to the immune synapse. Nat Cell Biol 11: 1332–1339, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qin Y, Meisen WH, Hao Y, Macara IG: Tuba, a Cdc42 GEF, is required for polarized spindle orientation during epithelial cyst formation. J Cell Biol 189: 661–669, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim J, Lee JE, Heynen-Genel S, Suyama E, Ono K, Lee K, Ideker T, Aza-Blanc P, Gleeson JG: Functional genomic screen for modulators of ciliogenesis and cilium length. Nature 464: 1048–1051, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodriguez-Fraticelli AE, Vergarajauregui S, Eastburn DJ, Datta A, Alonso MA, Mostov K, Martín-Belmonte F: The Cdc42 GEF Intersectin 2 controls mitotic spindle orientation to form the lumen during epithelial morphogenesis. J Cell Biol 189: 725–738, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Divjak M, Glare EM, Walters EH: Improvement of non-radioactive in situ hybridization in human airway tissues: Use of PCR-generated templates for synthesis of probes and an antibody sandwich technique for detection of hybridization. J Histochem Cytochem 50: 541–548, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang SO, Mathur S, Hattem G, Tassy O, Pourquié O: Sex-dimorphic gene expression and ineffective dosage compensation of Z-linked genes in gastrulating chicken embryos. BMC Genomics 11: 13, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thisse C, Thisse B: High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc 3: 59–69, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jaffe KM, Thiberge SY, Bisher ME, Burdine RD: Imaging cilia in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol 97: 415–435, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shao X, Somlo S, Igarashi P: Epithelial-specific Cre/lox recombination in the developing kidney and genitourinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1837–1846, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ritorto MS, Borlak J: A simple and reliable protocol for mouse serum proteome profiling studies by use of two-dimensional electrophoresis and MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Proteome Sci 6: 25, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]