Abstract

Objective

To assess the frequency of barriers to specialty care and to assess which barriers are associated with an incomplete specialty referral (not attending a specialty visit when referred by a primary care provider) among children seen in community health centers.

Study design

Two months after their child’s specialty referral, 341 parents completed telephone surveys assessing whether a specialty visit was completed and whether they experienced any of 10 barriers to care. Family/community barriers included difficulty leaving work, obtaining childcare, obtaining transportation, and inadequate insurance. Health care system barriers included getting appointments quickly, understanding doctors and nurses, communicating with doctors’ offices, locating offices, accessing interpreters, and inconvenient office hours. We calculated barrier frequency and total barriers experienced. Using logistic regression, we assessed which barriers were associated with incomplete referral, and whether experiencing ≥4 barriers was associated with incomplete referral.

Results

A total of 22.9% of families experienced incomplete referral. 42.0% of families encountered 1 or more barriers. The most frequent barriers were difficulty leaving work, obtaining childcare, and obtaining transportation. On multivariate analysis, difficulty getting appointments quickly, difficulty finding doctors’ offices, and inconvenient office hours were associated with incomplete referral. Families experiencing ≥4 barriers were more likely than those experiencing ≤3 barriers to have incomplete referral.

Conclusion

Barriers to specialty care were common and associated with incomplete referral. Families experiencing many barriers had greater risk of incomplete referral. Improving family/community factors may increase satisfaction with specialty care; however, improving health system factors may be the best way to reduce incomplete referrals.

Access to pediatric specialists has been cited by the American Academy of Pediatrics as an important measure of the Medical Home.1 Unfortunately, many children do not have access to specialty care. Children from families who are poor, of black race/ethnicity, or uninsured use less specialty care, and minorities report more problems accessing specialty care.2-4 One reason for low use of specialty care among underserved children may be an incomplete referral or not attending a pediatric specialty appointment when referred. Studies show that rates of incomplete referrals for children range from 14% to 20%,5,6 and rates may be as high as 30% in the community health center setting.7 Although the optimal rate of incomplete referral is not known,8 high rates are of concern because they may lead to persistence or exacerbation of health problems. Reducing rates of incomplete referral could be advantageous to health care systems because incomplete referrals may lead to inefficient use of provider time, system waste, and decreased access to pediatric specialists. Studies have shown that patient demographic factors, referral characteristics, and parent/provider communication may contribute to high rates of incomplete referral.7,9

Determining which barriers to specialty care are most prevalent and which ones are most likely to prevent specialty visits from occurring may be an important way to improve health care quality and access for children. Sobo et al10 have argued for a process-oriented model in approaching health care quality for underserved children. In this view, disparities in health care access arise in part because of barriers to care that moderate a child’s journey through the health care system. Although sociodemographic risk factors may modulate the effects of barriers to care, ultimately it is through process barriers that health disparities play out.10 As much of the navigation of health systems is done by parents, parents are in a good position to comment on the barriers that they face in attempting to access care for their children.11,12

In this study, we took a similar process-oriented approach in assessing barriers to specialty referral completion. Because barriers to care may be more pronounced in minority and underserved children,13,14 we set our study in 2 community health centers that primarily served a safety-net population, with a large proportion of immigrant and racial/ethnic minority families. We surveyed parents of children who had received a primary care provider referral to a pediatric specialist at an affiliated tertiary medical center. Our primary study questions were as follows: (1) In this community health center population, which were the most common family, community, and health care system barriers to specialty care; and (2) which barriers were most strongly associated with incomplete specialty referral?

Methods

We carried out a study of pediatric referrals from 2 community health centers to a tertiary care center. Previous reports from this study have described the relationships of patient demographic factors, referral characteristics, and provider/parent communication on specialty referral completion.7,9

A sample of 501 referred children was created using referral tracking documents, which are generated for every referral for appointment scheduling and insurance purposes. We collected all referral documents on alternate weeks during the first 4 weeks of the survey period (June 17, 2008, through July 2, 2008), and then on consecutive weeks from July 3, 2008, through January 28, 2009. From these records, we included referrals from a pediatric primary care provider to the tertiary care center for consultation with a specialist in one of the following pediatric specialties: allergy/immunology, cardiology, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, genetics, hematology/oncology, infectious disease, nephrology, neurology, neurosurgery, ophthalmology, orthopedics, otolaryngology, general surgery, pulmonology, rheumatology, and urology. These represented all pediatric specialty clinics meeting at least weekly at the tertiary medical center, except for adolescent medicine and psychiatry, which we excluded for reasons of child confidentiality.

Because of difficulties in distinguishing follow-up referrals from insurance reauthorizations (which often did not involve a new medical concern), we only included new referrals (referrals to a specialty clinic not visited in the previous 5 years or since birth). If multiple referrals were made for an individual child, we randomly selected one referral for inclusion. We included only children younger than 18 years of age and included only one referral per household. We excluded households in which neither English nor Spanish was spoken. This study was approved by the Partners HealthCare and the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Institutional Review Boards.

The survey focused on one referral episode for each child. The survey instrument used questions adapted from the US Census 2000,15 a previous survey about barriers to cancer care performed in our health center,16 and the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health.17 We additionally performed key informant interviews with health care providers and clinic staff to assess their views of frequent barriers to care. The final barriers we studied were a composite of relevant barriers from prior study as well as those mentioned frequently by clinic staff. Barriers fell into 2 overall domains: Family and community barriers included difficulty leaving work, obtaining childcare, obtaining transportation, and inadequate insurance; Health care system barriers included getting appointments quickly, understanding doctors and nurses, communicating with doctors’ offices, locating offices, accessing interpreters, and inconvenient office hours. Parents were asked how much they agreed with a statement about each barrier on a 4-part scale (eg, “It is hard to get out of work to go to appointments at [medical center]”). The text of each barrier item is shown in Table I (available at www.jpeds.com). The survey also collected demographic information about the parents and children. Parent demographic information included educational attainment, nativity, and race/ethnicity. Spanish translation for all written materials was performed by a certified translation specialist.

Table I.

Text of survey items

| Barrier | Text of survey item* |

|---|---|

| Leaving work | “It is hard to get out of work to go to appointments at [medical center].” |

| Childcare | “It is difficult to get child care so that you can go to appointments at [medical center].” |

| Transportation | “Transportation to [medical center] is a problem.” |

| Getting an appointment quickly | “You can get an appointment quickly at [medical center].” |

| Understanding providers | “At [medical center], it is hard to understand what doctors and nurses are saying to you.” |

| Communicating with office | “It is easy to communicate with the doctors’ offices at [medical center].” |

| Locating office | “It is easy to find doctors’ offices at [medical center].” |

| Interpreters unavailable | “Interpreter services are available at [medical center] if you need them.” |

| Inconvenient office hours | “At [medical center], office hours are convenient.” |

| Health insurance coverage | “[Child] has health insurance that pays for appointments at [medical center].” |

Stem: “Please tell me if each statement is true for you by answering definitely yes, somewhat yes, somewhat no, or definitely no.”

The survey sampling and fieldwork approaches were developed in a pilot study conducted in 2008. We used this approach to test accuracy of parent contact and language information as well as the number and mode of contacts needed to achieve adequate response rates. The parent survey was pilot-tested on a sample of 30 families. We modified survey items based on response patterns and feedback from interviewers.

Approximately 60 days after each referral, the referred child’s parent or guardian was contacted by mail via a bilingual advance letter. We chose this interval on the basis of a preliminary review of medical records, which suggested that >90% of specialist visits were completed or missed within 60 days. However, in cases in which the specialty visit was scheduled more than 60 days after the referral, we waited until the visit was completed or missed before contacting the family. All subjects who did not opt out were contacted via telephone, 10 to 14 days after the initial mailing, by a bilingual interviewer trained on the survey instrument and study protocol. The interview was performed with the parent who “knew the most about the health and healthcare” of the child. The interview lasted approximately 15 minutes. All surveys were fielded between July, 2008 and June, 2009.

Extraction of Electronic Health Record (EHR) Data

Additional demographic information was extracted from EHR registration data. The tertiary care center obtains registration information by parent telephone interview and updates it at least yearly. Additional factors included child sex, age at referral, race/ethnicity (categorized as black, Hispanic, other race, and white non-Hispanic), and insurance status (categorized as publicly insured, privately insured, or uninsured).

Statistical Analyses

We used χ2 tests to assess bivariate associations of each child and parent sociodemographic characteristic (child race/ethnicity, child sex, child age, insurance status, language of survey delivery, parent educational status, parent nativity, parent race/ethnicity) and each referral characteristic (medical versus surgical specialty, health center) with incomplete referral.

For each barrier to care, we dichotomized responses between “definitely” or “somewhat” yes versus “definitely” or “somewhat” no. Barriers that were positively phrased (“It is easy to find doctors offices at [medical center]”) were reverse coded. We then calculated the frequency of each barrier to care. For the barrier “leaving work,” we subset the analysis to only parents who “currently worked at a paid job.” For the barrier “interpreters unavailable,” we subset the analysis to only parents who “needed help communicating with doctors in English.”We examined the frequency distribution and median number of barriers experienced by families, and then used χ2 tests and ORs to examine the bivariate association of each individual barrier with incomplete referral.

We then used multivariate logistic regression to test the association of each barrier to care with incomplete referral, adjusting for child and parent sociodemographic characteristics. We developed a separate model for each barrier. The primary independent variable was the barrier, and the dependent variable was incomplete referral, a dichotomous variable which we defined as parent yes/no response to the item, “Has [child’s name] had the visit with the specialist yet?” Control variables included all parent and child sociodemographic characteristics excluding child race, as it correlated closely with parent race, and we limited insurance type to children with public versus private insurance, as our dataset only had two uninsured children. The model for “leaving work” was subset only to parents who worked. In the model of “interpreters unavailable,” we did not control for race/ethnicity, nativity, or survey language as these were collinear with the dependent variable. In the model for “health insurance coverage,” we did not control for insurance type.

We also examined the cumulative effect of barriers to care by examining bivariate and multivariate associations with incomplete referral among parents who experienced the highest quartile (≥4) barriers, among parents who experienced no barriers, and among parents who experienced all of the barriers associated with incomplete referral on previous multivariate analysis.

To test the generalizablity of our results, we used χ2 tests to compare EHR information for parent survey respondents versus nonrespondents. To test the validity of parent report as a measure of incomplete referral, we reviewed a random sample of 40 subjects’ medical records, assessing whether parent report of referral completion matched information in the child’s medical chart. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Overall, 341 of 501 parents completed the survey (68.1%). Nearly three-quarters of the sample children were Hispanic, and more than 70% were publicly insured. A total of 73% of parents were born outside of the US, and 57% took the survey in Spanish. Approximately two-thirds of the parents had less than a high school education (<13 years of education), and 27% had less than a middle school education (<9 years of education). Slightly more referrals were made to surgical specialties (55.7%) than medical specialties (44.3%). Overall, 22.9% of referrals were incomplete. See Table II for a full description of parent and child sociodemographic characteristics as well as referral characteristics.

Table II.

Characteristics of subjects and referrals

| Number and percent of total study population with characteristic (n = 341) |

Number and percent of subjects with characteristic having incomplete referral (n = 78) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | P † | |

| Child sociodemographic characteristics |

|||||

| Child race/ethnicity* | |||||

| Black | 15 | 4.5 | 4 | 26.7 | .69 |

| Hispanic | 248 | 74.9 | 60 | 24.3 | |

| Other race | 11 | 3.3 | 2 | 18.2 | |

| White non-Hispanic | 57 | 17.2 | 10 | 17.5 | |

| Sex* | |||||

| Female | 156 | 45 | 34 | 21.9 | .69 |

| Male | 185 | 54.3 | 44 | 23.8 | |

| Age* | |||||

| ≥5 years | 173 | 50.9 | 33 | 19.1 | .08 |

| <5 years | 167 | 49.1 | 45 | 27.1 | |

| Insurance status* | |||||

| Public | 243 | 71.3 | 58 | 24.0 | .61 |

| Uninsured | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | - | |

| Private | 96 | 28.2 | 20 | 20.8 | |

| Parent sociodemographic characteristics |

|||||

| Survey language | |||||

| English | 147 | 43.4 | 33 | 22.5 | .89 |

| Spanish | 192 | 56.6 | 44 | 23.0 | |

| Educational attainment‡ | |||||

| 0-9 years of education | 98 | 29.1 | 20 | 20.6 | .74 |

| 10-13 years of education | 128 | 38.0 | 32 | 25.0 | |

| <13 years of education | 111 | 32.9 | 25 | 22.5 | |

| Parent’s birthplace‡ | |||||

| Born in the US | 93 | 27.4 | 21 | 22.6 | .91 |

| Born elsewhere | 247 | 72.7 | 57 | 23.2 | |

| Parent race/ethnicity‡ | |||||

| Black | 9 | 2.7 | 1 | 11.1 | .14 |

| Hispanic | 260 | 77.2 | 64 | 24.7 | |

| Other Race | 10 | 3.0 | 4 | 40.0 | |

| White Non-Hispanic | 58 | 17.2 | 14 | 13.8 | |

| Referral characteristics | |||||

| Referral type* | |||||

| Medical§ | 150 | 44.1 | 30 | 20.0 | .25 |

| Surgical¶ | 190 | 55.9 | 48 | 25.3 | |

| Health center* | |||||

| A | 250 | 73.6 | 58 | 23.2 | .85 |

| B | 90 | 23.4 | 20 | 22.2 | |

Data obtained from child’s EHR.

P-value for χ2 test, comparing rates of incomplete referral for each subgroup.

Data obtained from parent telephone survey.

Dermatology, Otolaryngology, Neurosurgery, Ophthalmology, Orthopedics, Pediatric Surgery, Urology.

Allergy/Immunology, Cardiology, Endocrinology, Gastroenterology, Genetics, Hematology/Oncology, Infectious Disease, Nephrology, Neurology, Pulmonology, Rheumatology.

When we compared medical record information of survey nonrespondents versus respondents, we found modest differences: compared with respondents, nonrespondents were more likely to have registered their child’s race as white (27.3% vs 17.2%; P = .01) or other race (12.3% vs 3.3%; P < .001) and less likely to have registered their child’s race as Hispanic (52.6% vs 74.9%; P < .001). Nonrespondents were more likely to have been referred from health center B (41.4% vs 26.4%; P < .001). There were no differences between respondents and non-respondents in terms of child sex, child age, child insurance status, or medical versus surgical referral. To validate parent report of specialty referral completion, we sampled 40 random medical charts. For all but one record (97.5%), parent report of incomplete referral was confirmed as accurate by clinic notes in the medical record.

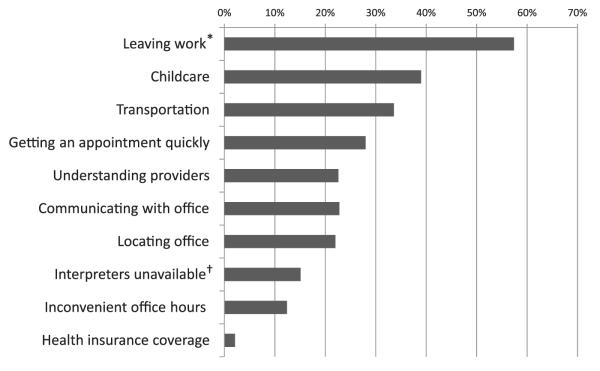

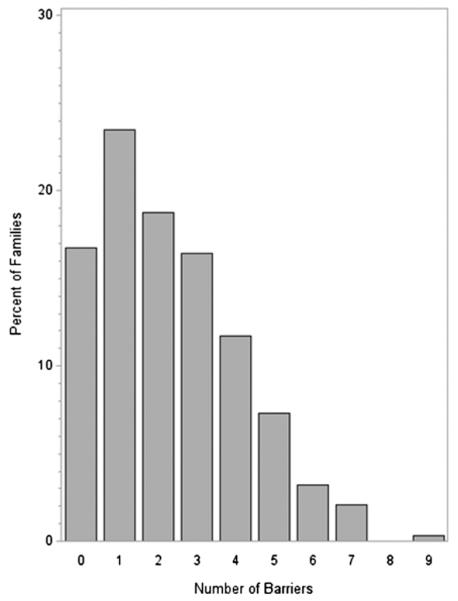

A total of 42% of parents experienced at least one barrier to specialty care. The most frequent barriers to care cited by parents were factors impacting access to the medical center: “leaving work” (57.4% of parents who “worked at a paid job”), “childcare” (39.0%), and “transportation” (33.6%). “Inconvenient office hours” (12.4%) and “health insurance coverage” (2.1%) were the least frequent barriers (Figure 1). The median number of barriers experienced was 2, with an IQR of 3 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Percent of families experiencing barriers to care (n = 341). Frequency of barriers. *Asked only if parent was “working a paid job.” †Asked only if parent “needed help communicating with doctors in English.”

Figure 2.

Number of barriers experienced by families (n=341).

Bivariate and Multivariate Associations with Incomplete Referral

When we examined the bivariate associations of each barrier to specialty care with incomplete referral, the barriers with the strongest associations with incomplete referral differed from the barriers that were most frequently cited by parents. For instance, “inconvenient office hours,” which was one of the less frequent barriers, had the strongest association with incomplete referral: 40% of parents who experienced this barrier reported incomplete referral (OR 2.88, 95% CI, 1.43-5.80). Other significant associations with incomplete referral were “locating office” (36.1% with this barrier reported incomplete referral; OR 2.71, 95% CI 1.52-4.84) and “getting an appointment quickly” (29.6% with this barrier reported incomplete referral; OR 1.89, CI 1.07-3.34; Table III). No sociodemographic or referral characteristics had bivariate associations with incomplete referral in this analysis (Table II), although some factors were associated in the larger medical record review study previously completed.7 After adjusting for child and parent sociodemographic characteristics, “inconvenient office hours,” “locating office,” and “getting an appointment quickly” maintained their associations with incomplete referral (Table III).

Table III.

Barrier frequency and association with incomplete referral

| Barrier | Number of subjects experiencing barrier (n = 341) |

Percent with barrier experiencing incomplete referral |

Unadjusted OR (CI) for incomplete referral for those with barrier |

aOR (CI) for incomplete referral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaving work* | 160 | 21.3 | 0.85 (0.44-1.66) | 0.87 (0.41-1.85)† |

| Childcare | 129 | 25.6 | 1.48 (0.87-2.51) | 1.64 (0.91-3.00)† |

| Transportation | 109 | 20.2 | 0.89 (0.51-1.57) | 0.84 (0.46-1.54)† |

| Getting an appointment quickly | 88 | 29.6 | 1.89 (1.07-3.34)‡ | 1.91 (1.05-3.46)†,‡ |

| Understanding providers | 73 | 19.2 | 0.88 (0.46-1.69) | 1.01 (0.51-2.01)† |

| Communicating with office | 73 | 28.8 | 1.71 (0.94-3.10) | 1.73 (0.91-3.30)† |

| Locating office | 72 | 36.1 | 2.71 (1.52-4.84)‡ | 2.70 (1.45-5.05)†,‡ |

| Interpreters unavailable§ | 22 | 31.8 | 1.85 (0.68-5.02) | 2.07 (0.73-5.91)∥ |

| Inconvenient office hours | 40 | 40.0 | 2.88 (1.43-5.80)‡ | 2.92 (1.38-6.21)†,‡ |

| Health insurance coverage | 7 | 28.6 | 1.41 (0.27-7.44) | 1.49 (0.27-8.31)¶ |

Asked only if parent was “working a paid job” (n = 198).

Adjusted for child age, sex, race/ethnicity, survey language, insurance status (public or private), parent nativity, and parental educational level.

Statistically significant.

Asked only if parent “needed help communicating with doctors in English” (n = 158).

Adjusted for child age, sex, race/ethnicity, survey language, parent nativity, and parental educational level.

Adjusted for child age, sex, insurance status (public or private), and parent educational level.

Cumulative Effects of Barriers

Both families with complete referrals and incomplete referrals experienced a median of 2 barriers to care (Figure 2). In addition, when we compared the 57 parents who experienced no barriers to specialty care with other parents who experienced at least one barrier, odds of incomplete referral were approximately the same (29.8% vs 21.6%; aOR 1.40; CI 0.70-2.81). However, the 83 families experiencing the highest quartile of barriers (4 or more barriers) were more likely to have incomplete referral when compared with other families: (33.7% vs 19.5%; aOR 2.24, CI 1.23-4.10). Among the 11 parents who experienced all 3 barriers found to be significantly associated with incomplete referral (“inconvenient office hours,” “locating office,” “getting an appointment quickly”), incomplete referral was more than twice as likely when compared with other parents (54.6% vs 21.9%; unadjusted OR 4.28; CI 1.27-14.44; no multivariate analysis performed because of sample size constraints).

Discussion

In this population, barriers to specialty care were common and were associated with incomplete referral. Approximately 1 in 4 referrals was incomplete, and more than 4 in 10 families experienced at least 1 of the 10 barriers to care about which we asked. Families who experienced the most barriers (≥4 barriers) were least likely to complete a referral. The results of this study suggest that specialty care is often quite difficult and often not possible to access for underserved families.

The most common barriers to care cited by parents were community factors that made accessing the tertiary medical center difficult: leaving work, childcare, and transportation. These barriers are likely to be particularly prevalent among underserved families, whose jobs often provide less flexibility18,19 and who may have fewer resources for childcare or transportation options.20,21 It is important to note, however, that none of these common community-level barriers was significantly associated with incomplete specialty referral. This finding suggests that, for the most part, parents were inconvenienced by these community level barriers, but they were able to overcome them.

In contrast, the barriers most strongly associated with incomplete referral were health system factors: inconvenient office hours, locating offices, and getting an appointment quickly. These findings suggest that health care systems may be able to improve rates of referral completion by improving office hours, directions, and relationships with front office staff. Given that work obligations and childcare were barriers commonly cited by parents, offering evening specialty clinic hours may help to improve both satisfaction and referral completion. Another option would be to offer open-access scheduling, which would decrease wait times, and has been shown to improve visit attendance in pediatric well care visits.22 Hospital greeters or patient navigators may help families locate specialists’ offices more easily.

This study adds to the current medical literature by suggesting that reducing health care system barriers such as the ones we found in this study may be one way to improve rates of specialty care usage among underserved children. The study’s strengths are its family-centered approach and its combination of parent survey data with data from the child’s EHR. In addition, our survey response rate (68%) was strong, given the difficulties of conducting survey research in underserved populations.

The study has a number of limitations. First, the study was set in 2 urban community health centers serving a largely Hispanic population. It is quite likely that many of the barriers that families face were particular to this patient population, geographical setting, or administrative setup, which may limit generalizability to other settings. For example, health insurance coverage was a relatively infrequent barrier, which may be in part attributable to robust health insurance programs for low-income children in Massachusetts. In addition, the community health centers were affiliated with the tertiary medical center and shared an EHR with it, which may have modified some of the barriers that families experienced. We did not study mental health or adolescent medicine referrals because of concerns about privacy. It is possible that these specialties experience different rates of incomplete referral and different barriers. Although we based our survey on key informant interviews and a previous instrument, it is likely that families experienced other barriers that we did not ask about in this survey. Subjects were surveyed about the barriers to care about 2 months after referral. We designed the study this way to prevent the survey process from reminding parents about the referral and therefore altering incomplete referral rates (the Hawthorne Effect). However, it is possible that families may have forgotten over time about the detailed barriers they experienced, or may have weighted some barriers more than others after they had completed their appointments. Finally, the study was limited to English and Spanish speakers. On the basis of medical record reviews, approximately 7% of families from these clinics speak a language other than Spanish or English. It is possible that these families experienced more barriers, or different barriers than the families we surveyed.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the Controlled Risk Insurance Company-Risk Management Foundation to K.Z. K.Z.’s effort also was partially funded by a National Research Service Award (T32 HP10018) from the Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, to the Harvard Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship.

We thank all of the community health center parents, providers, and administrators for their participation in the project. We additionally thank Esteban Barreto, Xin Cai, Gibran Minero, Michelle Connolly, Dianali Rivera, Tara Bryant, and Odeviz Soto for their assistance with data collection. The efforts of E.B., X.C., D.R., T.B., and O.S. were funded by a grant from the CRICO-Risk Management Foundation.

Footnotes

Portions of this study were presented during the Pediatric Academic Societies’ Meeting, April 28-May 1, 2012, Boston, MA.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002:184–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhlthau K, Nyman RM, Ferris TG, Beal AC, Perrin JM. Correlates of use of specialty care. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e249–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhlthau K, Ferris TG, Beal AC, Gortmaker SL, Perrin JM. Who cares for Medicaid-enrolled children with chronic conditions? Pediatrics. 2001;108:906–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer ML, Skinner AC, Slifkin RT. National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Unmet need for routine and specialty care: data from the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e109–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.e109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forrest CB, Shadmi E, Nutting PA, Starfield B. Specialty referral completion among primary care patients: results from the ASPN Referral Study. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:361–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourguet C, Gilchrist V, McCord G. The consultation and referral process. A report from NEON. Northeastern Ohio Network Research Group. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuckerman KE, Cai X, Perrin JM, Donelan K. Incomplete specialty referral among children in community health centers. J Pediatr. 2011;158:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forrest CB. Pediatric subspecialty referral completion. J Pediatr. 2011;158:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuckerman KE, Nelson K, Bryant TK, Hobrecker K, Perrin JM, Donelan K. Specialty referral communication and completion in the community health center setting. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11:288–96. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobo EJ, Seid M, Reyes Gelhard L. Parent-identified barriers to pediatric health care: a process-oriented model. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:148–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Homer CJ, Marino B, Cleary PD, Alpert HR, Smith B, Crowley Ganser CM, et al. Quality of care at a children’s hospital: the parents’ perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1123–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garwick AW, Kohrman C, Wolman C, Blum RW. Families’ recommendations for improving services for children with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:440–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngui EM, Flores G. Unmet needs for specialty, dental, mental, and allied health care among children with special health care needs: are there racial/ethnic disparities? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:931–49. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in US children. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e286–98. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Census Bureau [Accessed July 25, 2012];United States Census. 2000 http://www.census.gov/

- 16.Donelan K, Mailhot JR, Dutwin D, Barnicle K, Oo SA, Hobrecker K, et al. Patient perspectives of clinical care and patient navigation in follow-up of abnormal mammography. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:116–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics [Accessed July 25, 2012];The 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm.

- 18.Heymann SJ, Earle A. Low-income parents: how do working conditions affect their opportunity to help school-age children at risk? Am Educ Res J. 2000;37:833–48. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heymann SJ, Toomey S, Furstenberg F. Working parents: what factors are involved in their ability to take time off from work when their children are sick? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:870–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.8.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy KM, Tubbs CY, Burton LM. Don’t have no time: daily rhythms and the organization of time for low-income families. Family Relations. 2004;53:168–78. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henly JR, Lyons S. The negotiation of child care and employment demands among low-income parents. J Soc Iss. 2000;56:683–706. [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connor ME, Matthews BS, Gao D. Effect of open access scheduling on missed appointments, immunizations, and continuity of care for infant well-child care visits. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:889–93. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]