Abstract

Developing a sexual self-concept is an important developmental task of adolescence; however, little empirical evidence describes this development, nor how these changes are related to development in sexual behavior. Using longitudinal cohort data from adolescent women, we invoked latent growth curve analysis to: (1) examine reciprocal development in sexual self-concept (sexual openness, sexual esteem and sexual anxiety) over a four year time frame; (2) describe the relationship of these trajectories with changes in sexual behavior. We found significant transactional effects between these dimensions and behavior: sexual self-concept evolved during adolescence in a manner consistent with less reserve, less anxiety and greater personal comfort with sexuality and sexual behavior. Moreover, we found that sexual self-concept results from sexual behavior, as well as regulates future behavior.

Keywords: adolescent women, sexual self-concept, sexual behavior, latent growth curve modeling

Introduction

An Overview of Sexual Self-Concept and Dimensions

The development and consolidation of an understanding of one’s self as a sexual person, or sexual self-concept (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994; Cooley, 1902; Cyranowski & Andersen, 1998; James, 1915; Longmore, 1998; Rostosky, Dekhtyar, Cupp & Anderman, 2008; Snell, 1998; Winter, 1988), is a normative task of adolescence (Gagnon & Simon, 1987; Longmore, 1988; Rostosky, Dekhtyar, Cupp & Anderman, 2008). This understanding helps individuals organize and make sense of sexual experience and provide structure to and motivation for sexual behavior (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994; Andersen, Cyranowski, & Espindle, 1999; Birnbaum & Reis, 2006; Markus & Wurf, 1987). Recent work emphasizes the multi-dimensional nature of sexual self-concept, with individuals evaluating themselves across different dimensions (Garcia, 1999; O’Sullivan, Meyer-Bahlburg, & McKeague, 2006; Rostosky, Dekhtyar, Cupp & Anderman, 2008; Snell, 1998; Tolman, Striepe & Harmon, 2003). Many of these dimensions appear in early adolescence, often months or years before any physical sexual contact (Butler, Miller, Holtgrave, Forehand, & Long, 2006; Ott, Pfeiffer, & Fortenberry, 2006).

One dimension is sexual openness, which includes recognition of sexual pleasure or sexual arousal and a feeling of entitlement to pursue specific sexual activities (Horne & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2006; Nicholson, 1994). Thompson (1995) found a positive relationship between adolescent women’s realistic understanding of romance, their anticipation of sexual desire and their being ready to consent to sexual intercourse and to use condoms. Other research has shown that young women with a person-centered focus on sexuality report increased use of condoms and contraception, lower pregnancy rates and later onset of first sexual intercourse (Eng & Butler, 1996; Fine, 1988).

A second dimension of sexual self-concept, sexual esteem, involves positive evaluations of one’s sexuality (Snell, 1998), including appraisals of sexual thought, feelings and behaviors (Zeanah & Schwartz, 1996), as well perceptions of body in the sexual context (Horne & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2006). Generally speaking, adolescents with greater sexual esteem feel more assured in sexual situations, more positive about their sexual activity, and somewhat more likely to use condoms and contraception (Buzwell & Rosenthal, 1996; Seal, Minichello & Omode, 1997; O’Sullivan, 2006). Among late adolescent women, higher general sexual self-concept was associated with more sexual experience, including coitus and more sexual satisfaction, but was not associated with earlier onset of intercourse or with increased number of partner changes (Impett & Tolman, 2006). It may be that young women with higher sexual esteem place higher value on their sexual being and experiences, and by extension are willing to engage a sexual partner in discussing issues related to sexual encounters, such as satisfaction, emotions and willingness to participate in risk (Oattes & Offman, 2007).

A third dimension, sexual anxiety, refers to tension, discomfort, and other negative evaluations of the sexual aspects of one’s life (Snell, 1998). Sexual anxiety is associated with greater endorsement of abstinence beliefs, lower perceived sexual readiness or likelihood of intercourse in the near future, as well as with fewer reports of having a boyfriend, having been in love or having engaged in kissing, fondling or coitus (O’Sullivan et al., 2006). In this same study, older adolescents had lower negative sexual affect as compared to younger adolescents, suggesting that reduced negativity about sexual matters aligns with increasing sexual experience, perhaps as an anticipatory effect or increased confidence (O’Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2005). It is unclear, however, how a reduction in sexual anxiety may be influenced by a simultaneous rise in positive sexual self-concept, and how long this effect may last, particularly if sexual activity increases over time.

Developmental Change in Sexual Self-Concept and Sexual Behavior

Sexual self-concept and sexual behavior take on personal salience and social meaning in the post-pubertal period (Carpenter, 2002); even adolescents without direct experience of sexual behavior have a range of models drawn from family members, peers, education programs, and media (Hockenberry-Eaton, Richman, DiIorio, Rivero, & Maibach, 1996; Lindberg, Ku, & Sonenstein, 2000; Steele & Brown, 1995). Sexual self concept may also be influenced by meaningful sexual events occurring in this time frame, such as the initiation of new non-coital or coital behaviors, or the loss of virginity. New behaviors may shape (and reshape) generalizations about the sexual self, which may in turn influence the timing and choice of future sexual behaviors (Buzwell & Rosenthal, 1996; Houlihan et al., 2008; O’Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2005).

Some research suggests that dimensions of self-concept (e.g., capacity for close friendships and for romantic relationships) show development over time (Shapka & Keating, 2005). Alternatively, negative social attitudes toward adolescent sexuality suggest that specific dimensions of sexual self-concept could decline throughout adolescence, or could decline early and increase later (Harter, 1990). Some studies suggest that specific facets of self-concept are uni-directionally associated with sexual activity. For example, lower levels of general self-esteem predict subsequent sexual activity (Orr, Wilbrandt, Brack, Rauch & Ingersoll, 1989; Salazar et al., 2005; Spencer, Zimet & Orr, 2002). Other work demonstrates transaction between general cognition and risk behavior (Gerrard, Gibbons, Benthin, & Hessling, 1996); applied to the current study, sexual self-concept may display similar reciprocity with sexual behavior. Another study (Rostosky et al., 2008) found significant cross-sectional covaration between different dimensions of sexual self-concept, but did not examine any longitudinal associations. Additionally, the practice of sexual behavior may change as perceptions about the acceptability of sexual activity change, or as perceptions about the risks of coitus change. For example, vaginal sex may increase in frequency as young people develop a sexual repertoire guided by larger social scripts of normal and acceptable sexual practices (Gagnon, Giami, Michaels, & de Colomby, 2001).

Despite its developmental significance (Gagnon & Simon, 1987; Longmore, 1988; Rostosky et al., 2008), only a handful of studies have empirically linked adolescent women’s sexual self-concept and sexual behaviors; of these, most have examined sexual self-concept as an antecedent to sexual action, minimizing the dynamic reciprocal relationship between the sexual self-concept and specific sexual behaviors (Miller, Christensen & Olsen, 1987; Houlihan et al, 2008). Minimal information exists on how changes in one dimension of sexual self-concept influence changes in other dimensions, and, more commensurate with other work in early adolescent girls (O’Sullivan et al., 2006), whether these effects influence sexual behaviors into middle and later adolescence. Advancing sexual health among adolescent women requires better understanding the mutuality of relationships between aspects of the developing sexual self-concept and the behaviors they influence (Rostosky et al.,2008; Tolman et al., 2003). Using data collected from a longitudinal study of adolescent women’s sexual relationships and sexual behavior, the current study explicitly addresses this gap, posing two research questions (RQ):

RQ 1: What is the change in sexual openness, sexual esteem, sexual anxiety and coital frequency over time?

RQ 2: What is the reciprocal influence between sexual openness, sexual anxiety and sexual self-esteem? What is the influence with coital frequency?

To address these research questions, we specify models which empirically document the developmental reciprocity between sexual openness, sexual esteem, sexual anxiety and sexual behavior among adolescent women over a four year time frame.

Methods

Study Design and Procedure

Data were collected as part of a larger longitudinal cohort study of risk and protective factors (initiated in 1999) associated with sexually transmitted infections among adolescent women in middle adolescence (authors, 2005). Briefly, the larger study (initiated in 1999, completed in 2009), consisted of a three party study: daily sexual diaries, quarterly interviews and annual questionnaires. The current project focuses on developmental patterns in measures contained within the annual questionnaires; these questionnaires were conducted by trained research personnel who had multiple points of contact with study participants during the year with collection of other data and physical health information (Fortenberry, Temkit, Tu, Katz, Graham & Orr, 2005). Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and permission was obtained from a parent or legal guardian. This research was approved by the institutional review board of Indiana University/Purdue University at Indianapolis – Clarian.

At the time of analyses, the larger project was ongoing, and not every participant had completed the entire study. To maximize the number of interviews available for modeling in the current project, we selected a sub-sample of participants (324:83.7%) who had completed between two and four waves of data collection. Compared to the larger sample, this subsample was more likely to be African American (t = −3.771, p < .001) and younger (t = 2.287, p = .025) than those in the larger study (t = −3.771, p < .001). The subsample was not significantly different from the larger study sample in terms of oral genital, vaginal, anal sexual experience or any baseline level of sexual self-concept.

Using this subsample, we retained 1124 annual interviews for analyses., African American participants were more likely to have completed more waves of data collection (F[2,325] = 13.95, p < .001); no other differences were noted in terms of oral genital, vaginal, anal sexual experience or any baseline level of sexual self-concept.

Participants

For the larger project, young women (N=387, 90% African American) were recruited from one of three primary adolescent clinics in a large, urban city that serves primarily lower- and middle-income residents in areas with high rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection. To be eligible, patients had to be between 14 and 17 years old at enrollment (M = 15.87, SD = 0.76), speak English, and to not be pregnant at the time of enrollment. Sexual experience was not an eligibility requirement. After enrolling, participants contributed several sources of data, including annual interviews, providing information on sexual self-concept and sexual and contraceptive behaviors.

Measures

Sexual Self-Concept

We used a 17-item sexual-self concept scale, adapted from research on adults (Reynolds & Herbenick, 2003) and similar in content to items validated for adolescents (O’Sullivan et al., 2006) and for adults (Rostosky et al., 2006). All items were 4-point Likert type items assessing level of agreement (from “strongly disagree” [1] to “strongly agree” [4]).

To elicit dimensions, we performed factor analysis using principal components extraction with oblique rotation, eliminating three items with loading values less than 0.40 (listed in Table 1). Three factors accounted for 55.1% of the variance in these items. From these factors, we created three dimensions of sexual self-concept: sexual openness, sexual esteem and sexual anxiety. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the three subscales, respectively, was 0.85, 0.77 and 0.85. Individual measures and additional information are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for sexual self-concept dimensions over four years among (N=324) adolescent women.

| Enrollment | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Variables | M (SD) | Alpha | M (SD) | Alpha | M (SD) | Alpha | M (SD) | Alpha |

|

|

||||||||

| Sexual Openness* | 9.00 (2.86) | 0.80 | 9.20 (3.02) | 0.84 | 10.20 (3.09) | 0.85 | 10.20 (3.09) | 0.85 |

| Sexual Self-Esteem# | 8.00 (2.11) | 0.70 | 7.90 (2.03) | 0.71 | 10.20 (1.88) | 0.70 | 11.00 (1.68) | 0.77 |

| Sexual Anxiety^ | 8.80 (3.22) | 0.84 | 7.40 (2.71) | 0.84 | 7.10 (2.45) | 0.84 | 7.20 (2.61) | 0.85 |

| Coital Frequency, (log) | 1.12 (0.61) | - | 1.21 (0.59) | - | 1.28 (0.54) | - | 1.43 (0.58) | - |

Note: Sexual openness items include: I would be willing to try most kinds of sex at least once; There are some kinds of sex I would never do with anyone (reverse scored); I would be interested in trying a wide variety of sexual activities; I would be open to new and different sexual experiences. During factor analysis, loadings ranged in value from 0.79 to 0.81 and accounted for 23.8% of the variance in items. One item (Getting turned on is not as powerful an experience as people say it is) was dropped due to loading below 0.40.

Note: Sexual esteem items I like the ways in which I express my sexuality; I wish I were sexier (recoded); I feel I am a desirable person; My feelings about sex are an important part of who I am. During factor analysis, loadings ranged in value from 0.63 to 0.71 and accounted for 20.2% of the variance in all items. Two items (I really like my body; Having sex seems very important to others, but I don’t really see what the big deal is) were dropped due to loading below 0.40.

Note: Sexual anxiety items included: Sometimes in sexual situations I worry that things will get out of hand; When I am in a sexual situation, I am confused about what I want to happen; I worry about being taken advantage of sexually; In sexual situations, I am comfortable and sure about what to do (reverse scored); Sometimes in sexual situations it is difficult for me to relax. During factor analysis, loadings ranged in value from 0.68 to 0.89, and accounted for 11.6% of the variance in all items.

Sexual behavior

The sexual behavior variable, coital frequency, was an aggregate of quarterly reports within each study year of vaginal intercourse events (“In the past three months, how many times did you have sex with [X]?”) for a given study year. Formative research with the study population indicated that “sex” used in this context indicated penile-vaginal intercourse. Because this measure had a skewed distribution, its logarithm was used in all models.

Statistical Procedure

In a structural equation modeling framework, latent growth curve (LGC) modeling is a flexible and powerful method for the analysis of longitudinal data, and was used to examine developmental patterns in this paper. A myriad of studies describe this method (e.g., Bollen & Curran, 2006; Curran & Hussong, 2002; Duncan, Duncan, Strycker, Li, & Alpert, 1999). The within person change trajectory is expressed through the estimation of latent variables: a latent intercept factor accounts for an average initial level in a variable and a latent slope factor is associated with average growth or change. Variances around these latent factors reflect inter-individual differences in initial levels and rates of change (Curran & Willoughby, 2003).

Analyses were conducted in two steps. The first step addressed Research Question 1 (assess the unique developmental trajectory of coital frequency, sexual openness, sexual anxiety and sexual esteem). We estimated several linear, nonlinear and autoregressive-latent trajectory (ALT) models for sexual openness, sexual self-concept, sexual esteem and coital frequency to find the functional form that best described each variable’s unique trajectory. Final model selections (Table 2) were based upon fit improvement of nested models (Bollen & Curran, 2004; Curran & Bollen, 2001) or, in the case of non-nested models, upon changes in the incremental fit index (IFI) and RMSEA (Bollen & Curran, 2006).

Table 2.

Single trajectory model comparison and final model estimates

| Model Fit Indices | Model Comparison | Unconditional Estimates of Model Retained | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Model | X2(df) | p | CFI | RMSEA | Models Compared | ΔX2(df) | p(d) | Intercept M | Intercept Var | Slope M | Slope Var | Slope/Int Covariance | AR Values+ | FL Values++ |

| Sexual Openness ^ Two-factor | ||||||||||||||

| LGC | 4.37(5) | 0.32 | 0.998 | 0.023 | - | 8.97(0.16)*** | 5.54(0.77)*** | 0.59(0.06)*** | 0.41(0.15)** | −0.68(0.28)** | ||||

| FL LGC | 2.31(3) | 0.32 | 0.989 | 0.019 | 2 vs 1 | 2.06(2) | n/s | All n/s | ||||||

| AR LGC | 0.02(2) | 0.93 | 0.936 | 0.000 | 3 vs. 1 | 4.35(3) | n/s | All n/s | - | |||||

| Sexual esteem ^ Two-factor | ||||||||||||||

| LGC | 6.91(5) | 0.14 | 0.936 | 0.046 | - | 7.89(0.11)*** | 2.12(0.36)*** | 0.12(0.05)*** | 0.18(0.07)** | −0.30(0.14)* | ||||

| FL LGC | 1.38(3) | 0.51 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 2 vs 1 | 5.51(2) | n/s | All n/s | ||||||

| AR LGC | 0.05(2) | 0.91 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 3 vs. 1 | 6.86(3) | n/s | All n/s | - | |||||

| Sexual Anxiety Two-factor | ||||||||||||||

| LGC | 38.71(5) | <.000 | 0.000 | 0.141 | - | - | ||||||||

| ^ FL LGC | 7.63(3) | 0.22 | 0.989 | 0.037 | 2 vs 1 | 34.30(2) | <.05 | 8.82(0.18)*** | 9.99(6.93) | −1.67(0.23)& | 8.42(7.26) | −7.79(7.12) | 0.86(0.11)*** | |

| AR LGC | 8.71(2) | 0.11 | 0.880 | 0.071 | 3 vs. 1 | 30.00(3) | <.05 | All n/s | 0.97(0.08)*** | |||||

| Coital Frequency Two-factor | ||||||||||||||

| LGC | 13.18(5) | 0.12 | 0.969 | 0.045 | - | |||||||||

| FL LGC | 7.11(3) | 0.11 | 0.973 | 0.051 | 2 vs 1 | 6.07(2) | <.05 | 0.26(0.14) | ||||||

| AR LGC | 6.03(2) | 0.09 | 0.977 | 0.060 | 3 vs. 1 | 5.45(3) | n/s | - | 0.23(0.50) | |||||

| ^ AR, FL LGC | 0.03(1) | 0.62 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 4 vs 3 | 7.21(1) | <.05 | 1.05(0.02)*** | 0.31(0.04)*** | 0.12 (0.01)*** | 0.03(0.01)*** | 0.05(0.02)*** | 0.67(0.23)* | All n/s |

Note: CFI = comparative fit index, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation, AR=autoregressive, FL=freed loading.

Note: A three factor (intercept, slope and quadratic) functional form was evaluated for sexual anxiety, but not retained, due to negative error variance and fit degradation.

Model retained

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Presented in time order (e.g., Year 1 to Year 2, Year 2 to Year 3 and Year 3 to Year 4)

Freed loadings are presented in order according the format utilized: (0, __, __, 1 for sexual anxiety; 0, 1, __, ___ for coital frequency, giving and receiving oral sex, sexual openness and sexual esteem)

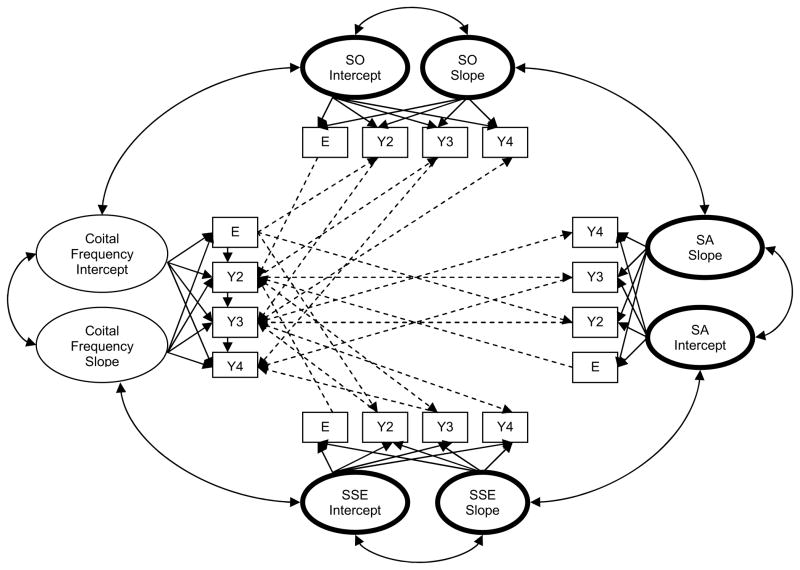

The second step addressed Research Question 2 (assess the reciprocal influences of sexual openness, sexual anxiety and sexual esteem, independently and controlling for coital frequency). First, we estimated sexual openness, sexual anxiety and sexual esteem in an unconditional triple-trajectory growth curve in which intercept and slope factors on all variables were covaried. Next, retaining this model, we added the latent slope and intercept from coital frequency, adding covariances between these factors to the other latent factors (Figure 1). All models also controlled for cross-lagged influences between the observed time points of all sexual self-concept variables, and the coital frequency variable.

Figure 1.

Conceptual triple-trajectory latent growth curve model of sexual openness, sexual esteem, sexual anxiety and coital frequency.

Note: (a) Latent factors in bold indicate variables used independently and with coital frequency. (b) Across variable latent factor covariances are illustrated by bold double headed arrows. For illustration purposes, only four of these paths are shown. (c) Within-variable latent factor covariances are represented by regular double headed arrows. (d) Cross lagged effects are shown as dotted single-headed arrows. (e) Latent factor loadings are shown with solid single headed arrows (1,1,1,1 for intercepts; 0,1,2,3 for sexual openness, sexual esteem and sexual anxiety slope; 0, __, __, 1 for coital frequency slope). (f) The observed variable error terms have also been covaried at similar time frames (e.g., throughout enrollment, throughout Year 2, etc.) but are not shown.

All analyses were conducted in AMOS, 17.0, using full information maximum likelihood estimation to account for different numbers of waves contributed by respondents.

Results

Developmental Change within Sexual Openness, Sexual Esteem, Sexual Anxiety and Coital Frequency

Model comparison statistics and unstandardized model estimates associated with best fitting models are shown in Table 2. Model fit indices suggest excellent fit of the data to the model.

Sexual openness and sexual esteem had a significant intercept mean and a significant, positive slope mean, suggesting meaningful developmental growth from initial levels in both dimensions over four years. Significant intercept and slope variance for both dimensions underscore meaningful individual variability in both initial levels of sexual openness and sexual esteem, as well as individual differences in growth in these dimensions over time. Higher initial levels of sexual esteem were associated with slower growth over time (r = −0.505, p < .001); similar within-dimension change was noted for sexual esteem (r = −0.238, p < .05).

Sexual anxiety showed a significant intercept mean and a significant, negative slope, but non-significant variance in either latent factor, suggesting similarity across adolescent women in initial levels of sexual anxiety and similarity in levels of decline over four years. Freed loadings suggest that 71% of decline in sexual anxiety for young women occurred between enrollment and Year 2 (first free parameter: b = 0.88, SE = 0.11, p < .001; B = 0.71) and 17% of change (decrease) occurred between Year 2 and Year 3, with about 12% of change (increase) in sexual anxiety from Year 3 to Year 4 (second free parameter: b = 1.05, SE = 0.11, p < .001; B = 0.93) (Bollen & Curran, 2006).

An autoregressive LGC model provided the best fit for the coital frequency trajectory. A significant intercept mean and significant slope mean, as well as a significant intercept and slope variance, suggested growth in coital frequency over four years, with individual variability around initial rates of coitus and in growth rates across adolescent women. Higher levels of initial coital frequency were associated with slower growth over time (r = −0.851, p < .001).

Developmental Change between Sexual Openness, Sexual esteem, Sexual Anxiety

Higher initial sexual openness was associated with higher initial sexual esteem (r = 0.554, p < .001) and with attenuated growth in sexual esteem (r = −0.670, p < .001). Higher initial sexual esteem correlated with attenuated growth in sexual openness (r = −0.337, p = .007); growth in sexual openness was related to growth in sexual esteem (r = 0.735, p < .001).

Higher initial sexual anxiety was associated with slower growth in sexual esteem (r = −0.342, p = .006); decline in sexual anxiety was associated with accentuated growth in sexual esteem (r = 0.260, p < .001). Sexual anxiety was not correlated with sexual openness (Table 3). Model fit indices suggest excellent fit of the model to the data.

Table 3.

Model estimates (Cov [SE]), unconditional triple latent growth curve model for sexual openness, sexual esteem and sexual anxiety and unconditional quadruple trajectory latent growth curve for sexual openness, sexual esteem, sexual anxiety and coital frequency, over a four year time frame among adolescent women (N=324).

| Sexual Openness Intercept | Sexual Openness Slope | Sexual Esteem Intercept | Sexual Esteem Slope | Sexual Anxiety Intercept | Sexual Anxiety Slope | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Triple Trajectory Model | Sexual Openness Intercept | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sexual Openness Slope | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Sexual Esteem Intercept | 1.72 (0.30)*** | −0.32 (0.12)** | - | - | - | - | |

| Sexual Esteem Slope | −0.56 (0.13)*** | 0.20 (0.05)*** | - | - | - | - | |

| Sexual Anxiety Intercept | 1.02 (0.47)* | −0.15 (0.20) | 0.35 (0.12) | −0.36 (0.62)** | - | - | |

| Sexual Anxiety Slope | −0.11 (0.42) | 0.12 (0.17) | −0.48 (0.28) | 0.23 (0.12) | - | - | |

|

| |||||||

| Quadruple Trajectory Model | Coital Frequency Intercept | 0.78 (0.19)*** | −0.09 (0.05)^ | 0.26 (0.08)*** | −0.14 (0.04) | −0.24 (0.12)* | −0.25 (0.09)* |

| Coital Frequency Slope | −0.19 (0.14) | −0.14 (0.05)** | 0.08 (0.10) | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.12 (0.014) | −0.19 (0.11)^ | |

Note: The quadruple trajectory model controlled for associations between all sexual self concept domains, cross lagged paths between sexual self-concept domains and coital frequency domains; estimates are not shown.

Model fit indices: χ2(df) = 41.29(31); CFI = 0.995; RMSEA (90% CI) = .017 (.000 – .044) (triple trajectory model); χ2(df) = 128.07(60), p <.05, CFI = 0.928, RMSEA (90% CI) =0.059 (.044 – .074) (quadruple trajectory model).

p < .10;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Freed loadings for sexual anxiety: (0, __, __, 1); values b[SE]): 0.81 (0.11)**, 0.92 (0.10)**

Freed loadings for coital frequency: (0, 1, __, ___); values b[SE]): 02.12 (0.06)**; 1.06 (0.92)**

Developmental Change between in Sexual Openness, Sexual esteem, Sexual Anxiety and Coital Frequency

Higher initial coital frequency was associated with higher initial sexual openness (r = 0.331, p < .001), higher initial sexual esteem (r = 0.582, p < .001) and lower initial sexual anxiety (r = −0.202, p = .045). Higher initial coital frequency was marginally associated with a slower growth in sexual openness (r = −0.224, p = .078), as well as accentuated decline in sexual anxiety (r = −0.314, p = .079), Growth in sexual openness positively correlated with growth in coital frequency (r = 0.418, p < .001); slower decline in sexual anxiety was associated with slower growth in coital frequency (r = −0.497, p = .012) (Table 3). Model fit indices suggest excellent fit of the model to the data.

Discussion

This research evaluates transactional development between dimensions of sexual self-concept and in sexual behavior during adolescence. These findings suggest that sexual self-concept is comprised of multiple dimensions, each with an identifiably unique trajectory evolving during adolescence in a manner consistent with less reserve, less anxiety and greater personal comfort with sexuality and sexual behavior. Similarly, vaginal intercourse also becomes a more common aspect of young women’s lives over time. These psychological and behavioral processes are closely linked developmentally, with dimensions of sexual self-concept simultaneously resulting from sexual behavior, as well as differentially influencing future behavior (Longmore, 1998; Markus & Wulf, 1987).

In line with prior research (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994; O’Sullivan et al., 2006), we found that sexual openness and sexual esteem increased, while sexual anxiety decreased, during a four-year period across middle and late adolescence. On the one hand, these findings could indicate that an accumulation of experiences generally bolsters confidence and reduces negativity about sexual matters, or that young women without intercourse experience begin to view sex in more positive terms as they gain confidence in pre-intercourse activities or anticipate their first sexual encounter (O’Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2005). On the other hand, a later increase in sexual anxiety may be tied to re-emergence of concerns about reputation or competence as young women acquire new partners or expand their sexual repertoire (Bersamin, Walker, Fisher, & Grube, 2006). Moreover, significant variation in initial levels and change patterns in these dimensions likely reflect developmental differences in ranges of experiences and perceptions about the sexual self, with those higher in self-concept experiencing less growth over time.

Also in support of prior work, (Centers for Disease Control, 2006), coital frequency increased over time. In adult women, higher coital frequency is associated with increased relationship stability (Waite & Joyner, 2001), particularly in more established dyads, with some decline in frequency noted after the first months or years of the relationship (Rao & DeMaris, 1995; Tanfer & Cubbins, 1992). Less is known about coital frequency among adolescent women. We have shown that increased coital frequency is associated with higher relationship quality over time (Sayegh, Fortenberry, Anderson & Orr, 2005), whereas other research suggests that coitus plays multiple roles in adolescent relationships (Crawford & Popp, 2003; Jackson & Cram, 2003; Tolman, 2002). However, because coital frequency and relationship quality are inversely associated with condom use (Fortenberry et al., 2005), additional contextual attention to this issue is warranted.

An important contribution from our work is the demonstration of developmental reciprocity between dimensions of sexual self-concept and sexual behavior. Sexual esteem was positively correlated with sexual openness, suggesting in part that increasing positive feelings about one’s sexuality may be complementary to growth in one’s acquisition of new or different sexual experiences. This idea is partially reinforced in consideration that decline in sexual anxiety were linked to growth in sexual esteem. While there was not a corresponding effect between sexual anxiety and sexual openness, it may be that the reduction in negativity about sexual behavior works through growth in sexual esteem, serving to promote a young women’s participation in different behaviors over time. Parallel to other work on early adolescent women (O’Sullivan et al., 2006), we found that higher initial sexual openness was positively correlated with greater levels of sexual activity, and that sexual anxiety initially corresponds with lower levels of coital frequency. Additionally, growth in sexual openness and decline in sexual anxiety were both associated with increased coital frequency over time. Participation in coitus over time may anchor confidence and reduce anxiety about sexuality, which in turn, creates a positive environment for additional sexual behavior to occur.

In sum, these findings point to the changing meaning of sexual self-concept among young women over time, as well as the integration of these meanings with one’s sexual behavior at different points in time. Our data contradict the notion that adolescent sexuality is impulsive and sporadic; rather, we suggest that sexual self-concept expands across development and is influential on, and responsive to, experience. As pleasurable experiences in new situations are repeated, comfort with one’s sexual self is likely to increase, and anxiety surrounding involvement in sex is likely to diminish. The coherence of these developmental trajectories creates a markedly different perspective on young women’s sexuality that is usually depicted as accidental or coerced and is primarily notable for its adverse outcomes (Fortenberry, 2003; Schalet, 2004). Rather, we suggest that sexual self-concept evolves in an iterative fashion whereby experiences both modifying and reinforcing a sense of oneself as a sexual person becomes increasingly integrated over time (Giordano, Longmore & Manning, 2006). These results also underscore the importance of remembering that “sexual experience” is more than a euphemism for whether one has had intercourse. Rather, sexual experience is a process by which the sexual self is linked to specific experiences, behaviors and emotions and is recalibrated accordingly as one’s sexual repertoire and its associated meanings expand.

Limitations of the study include the fact that the research sample was recruited from clinics and was relatively homogeneous in terms of race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and geographic residence, and is not representative of all adolescent women. Although about 25% of the sample had not had vaginal intercourse at the time of enrollment, it is likely that this sample (on average) was more involved in coital sexual behaviors at earlier ages than would be found in a random sample of American adolescent women. However, we find little reason to propose marked differences for other groups of adolescent women in the developmental trajectories of sexual self-concept and sexual behaviors. It should also be noted that the sample did include young women with a wide range of sexual self-concept and sexual experiences. Future research should elucidate which demographic characteristics and sexual experiences, both non-coital (e.g., genital touching or oral genital sex) and coital (e.g., vaginal or anal) compel more radical changes in sexual self-concept; for example, do some specific experiences (e.g., first coitus) represent pivotal moments or milestones more so than others, and if so, how does the perception of reaching these events influence an adolescent’s sexual self? Moreover, little is known about the link between adolescent sexual self-concept and adult sexual self-concept. It would be useful to understand how experiences in younger years serve a buffer to, or increase exposure to, risk in later years. Additionally, future research may seek to replicate these findings in a sample of young men and/or focus on the development of sexual self-concept within the confines of romantic and sexual relationships.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NICHD grant R01 HD044387, and two grants from NAIAD (U19 AI31494 and a T32 grant). The authors would like to thank Amanda E. Tanner for reading earlier versions of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Devon J. Hensel, Email: djhensel@iupui.edu.

J. Dennis Fortenberry, Email: jfortenb@iupui.edu.

Lucia F. O’Sullivan, Email: osulliv@unb.ca.

Donald P. Orr, Email: dporr@iupui.edu.

References

- Andersen BL, Cyranowski JM. Women’s sexual self-schema. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1994;67:1079–1100. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen BL, Cyranowski JM, Espindle D. Men’s sexual self-schema. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1999;76:645–661. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin MM, Walker S, Fisher DA, Grube JW. Correlates of oral sex and vaginal intercourse in early and middle adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:59–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum GE, Reis HT. Women’s sexual working models: An evolutionary-attachment perspective. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:328–342. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models: A synthesis of two traditions. Sociological Methods and Research. 2004;32:336–383. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent Curve Models: A Structural Equation Approach. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Breakwell GM, Millward LJ. Sexual self-concept and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Adolescence. 1997;20:29–41. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. 1. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Butler TH, Miller KS, Holtgrave DR, Forehand R, Long N. Stages of sexual readiness and six-month stage progression among African-American pre-teens. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:378–386. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzwell S, Rosenthal D. Constructing a sexual self: Adolescents’ sexual self-perceptions and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6:489–513. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LM. Gender and the meaning and experience of virginity loss in the contemporary United States. Gender and Society. 2002;16:345–365. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(SS-5):1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH. Human nature and the social order. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons; 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford M, Popp D. Sexual Double Standards: A Review and Methodological Critique of Two Decades of Research. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40(1):13–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bollen KA. The best of both worlds: Combining autoregressive and latent curve models. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Hussong AM. Structural equation modeling of repeated data: Latent curve analysis. In: Moskowitz DS, Hershberger SL, editors. Modeling Intraindividual Variability with Repeated Measures Data: Methods and Applications. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Willoughby MT. Implications of Latent Trajectory Models For the Study of Developmental Psychopathy. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:581–612. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Andersen BL. Schemas, sexuality, and romantic attachment. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1998;74:1364–1379. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Li F, Alpert A. An Introduction to Latent Variable Growth Curve Modeling: Concepts, Issues and Applications. New Jersey: Earlbaum Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Eng TR, Butler WT. Tracking the Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases. London: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman L, Holowaty P, Harvey B, Rannie K, Shortt L, Jamal A. A comparison of the demographic, lifestyle, and sexual behaviour characteristics of virgin and non-virgin adolescents. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 1987;6:197–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman M, Caldwell C. Growth Trajectories of Sexual Risk Behavior in Adolescence and Young Adulthood. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(6):1096–1101. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine M. Sexuality, Schooling, and Adolescent Females: The Missing Discourse of Desire. Harvard Educational Review. 1988;58(1):29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD. Adolescent sex and the rhetoric of risk. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing Adolescent Risk: Toward an Integrated Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2003. pp. 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD, Temkit M, Tu W, Katz BP, Graham CA, Orr DP. Daily mood, partner support, sexual interest and sexual activity among adolescent women. Health Psychology. 2005;24:252–257. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon JH, Giami A, Michaels S, de Colomby P. A comparative study of the couple in the social organization of sexuality in France and the United States. Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon JH, Simon W. The sexual scripting of oral genital contacts. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1987;16:1–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01541838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia LT. The certainty of the sexual self-concept. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 1999;8:263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Benthin AC, Hessling RM. A longitudinal study of the reciprocal nature of risk behaviors and cognitions in adolescents: What you do shapes what you think, and vice versa. Health Psychology. 1996;15:344–354. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Longomreo MA, Manning WD. Gender and the meanings of adolescent romantic relationships: A focus on boys. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:260–287. [Google Scholar]

- Graham CA, Sanders SA, Milhausen RR, McBride KR. Turning on and turning off: A focus group study of the factors that affect women’s sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33:527–538. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044737.62561.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2003. MMWR Surveillance Summary. 2004;53:1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunseit A, Richters J, Crawford J, Song A, Kippax S. Stability and change in sexual practices among first-year Australian university students (1990–1999) Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2005;34:569–582. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-6281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Self and identity development. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the Threshold: The Developing Adolescent. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 352–387. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hockenberry-Eaton M, Richman MJ, DiIorio C, Rivero T, Maibach E. Mother and adolescent knowledge of sexual development: the effects of gender, age, and sexual experience. Adolescence. 1996;31:35–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan A, Gibbons F, Gerrard M, Yeh H, Reimer R, Murry V. Sex and the self. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28(1):70–91. [Google Scholar]

- Horne S, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Female sexual subjectivity and well-being: Comparing late adolescents with different sexual experiences. Sexual Research and Social Policy. 2005;2:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Impett E, Tolman D. Late Adolescent Girls’ Sexual Experiences and Sexual Satisfaction. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21(6):628–646. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SM, Cram F. Disrupting the sexual double standard: Young women’s talk about heterosexuality. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2003;42:113–127. doi: 10.1348/014466603763276153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. Psychology. New York: Henry Holt; 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg LD, Ku L, Sonenstein F. Adolescents’ reports of reproductive health education, 1988 and 1995. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA. Symbolic interactionism and the study of sexuality. The Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Wurf E. The dynamic self-concept: A social psychological perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 1987;38:299–337. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC, Christensen RB, Olson TD. Adolescent self-esteem in relation to sexual attitudes and behavior. Youth & Society. 1987;19:93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer SF, Udry JR. Oral sex in an adolescent population. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1985;14:41–46. doi: 10.1007/BF01541351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson P. Anatomy and destiny: Sexuality and the female body. In: Choi P, Nicolson P, editors. Female sexuality. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Oattes M, Offman A. Global self-esteem and sexual esteem as predictors of sexual communication in intimate relationships. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2007;16(3/4):89–100. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Brooks-Gunn J. The timing of changes in girls’ sexual cognitions and behaviors in early adolescence: A prospective, cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, McKeague IW. The development of the sexual self-concept inventory for early adolescent girls. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Orr DP, Wilbrandt ML, Brack CJ, Rauch SP, Ingersoll GM. Reported sexual behaviors and self-esteem among young adolescents. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1989;143:86–90. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150130096023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott MA, Pfeiffer EJ, Fortenberry JD. Early and middle adolescent perceptions of abstinence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao KV, DeMaris A. Coital frequency among married and cohabiting couples in the United States. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1995;27:135–150. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000022653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez L. Oral sex among adolescents: Is it sex or is it abstinence? Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32:298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds MA, Herbenick DL. Using computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) for recall of childhood sexual experiences. In: Bancroft J, editor. Sexual Development in Childhood. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press; 2003. pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky S, Dekhtyar O, Cupp P, Anderman E. Sexual self-concept and sexual self-efficacy in adolescents: A possible clue to promoting sexual health? Journal of Sex Research. 2008;45(3):277–286. doi: 10.1080/00224490802204480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar LF, Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Lescano CM, Brown LK, et al. Self-esteem and theoretical mediators of safer sex among African-American female adolescents: Implications for sexual risk reduction interventions. Health Education & Behavior. 2005;32:413–427. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh MA, Fortenberry JD, Anderson JG, Orr DP. Effects of relationship quality on chlamydia infection among adolescent women. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:163e1–163e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalet A. Must we fear adolescent sexuality? Medscape General Medicine. 2004;6(4):44, 644. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal A, Minichiello V, Omodei M. Young women’s sexual risk-taking behaviour: Re-visiting the influences of sexual self-efficacy and sexual esteem. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1997;8:159–165. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapka JD, Keating DP. Structure and change in self-concept during adolescence. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2005;37:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GE, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Self-esteem and the relation between risk behavior and perceptions of vulnerability to unplanned pregnancy in college women. Health Psychology. 1997;16:137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE. The multidimensional sexual self-concept questionnaire. In: Davis CM, Yarber WL, Bauserman R, Schreer G, Davis SL, editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 521–524. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JM, Zimet GD, Aalsma MC, Orr DP. Self-esteem as a predictor of initiation of coitus in early adolescents. Pediatrics. 2002;109:581–584. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele JR, Brown JD. Adolescent room culture: Studying media in the context of everyday life. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:551–576. [Google Scholar]

- Tanfer K, Cubbins LA. Coital frequency among single women: Normative constraints and situational opportunities. Journal of Sex Research. 1992;29:221–250. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. Going All the Way. New York: Hill and Wang; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL. Dilemmas of Desire: Teenage Girls Talk about Sexuality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, Striepe MI, Harmon T. Gender matters: constructing a model of adolescent sexual health. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:4–12. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Joyner K. Emotional satisfaction and physical pleasure in sexual unions: Time horizon, sexual behavior and sexual exclusivity. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:247–264. [Google Scholar]

- Winters L. The Role of Sexual Self-Concept in the Use of Contraceptives. Family Planning Perspectives. 1988;20:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah PD, Schwartz JC. Reliability and validity of the sexual esteem inventory for women. Assessment. 1996;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]