Background: MiR-302 regulates pluripotency genes and helps somatic cell reprogramming.

Results: Tranilast promotes miR-302 expression and somatic cell reprogramming via AhR.

Conclusion: MiR-302 can be up-regulated by AhR ligands to induce pluripotency.

Significance: Activation of AhR facilitates somatic cell reprogramming.

Keywords: Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor, Induced Pluripotent Stem (iPS) Cell, microRNA, Reprogramming, Small Molecules, Tranilast

Abstract

MiR-302 has been shown to regulate pluripotency genes and help somatic cell reprogramming. Thus, promotion of endogenous miR-302 expression could be a desirable way to facilitate cell reprogramming. By using a luciferase reporter system of the miR-302 promoter, we screened and found that an anti-allergy drug, tranilast, could significantly promote miR-302 expression. Further experiments revealed that two aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) binding motifs on the miR-302 promoter are critical and that activation of AhR is required for tranilast-induced miR-302 expression. Consistently, not only tranilast but other AhR agonists promoted miR-302 expression. Furthermore, the activation of AhR facilitated cell reprogramming in a miR-302-dependent way. These results elucidate that miR-302 expression can be regulated by AhR and thus provide a strategy for promoting somatic cell reprogramming by AhR ligands.

Introduction

Introduction of defined combinations of transcription factors into somatic cells leads to the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)3 (1–3). Enormous efforts have been made to improve the reprogramming efficiency as well as avoid the integration of transgenes into the genome (4–6). Moreover, rationalization of the molecular mechanisms underlying the reprogramming process should also contribute to identifying better strategies of efficient reprogramming (7, 8). Thus far, epigenetic modifiers (9), inhibitors of GSK-3β (10), TGF-β inhibitors (11) and MEK inhibitors (10), antioxidants (12), longevity-promoting compounds (13) as well as others have been shown to enhance the generation of iPSCs.

MiR-302 is a polycistronic miRNA cluster including miR-302b/c/a/d and miR-367. These miRNAs share the same promoter and are generated from the same primary transcript (14). MiR-302 is highly expressed in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (15, 16). Recent reports show that pluripotency factors Oct4 and Sox2 bind to the promoter region of miR-302 and tightly regulate miR-302 expression (17, 18). The expression level of miR-302 correlates well with the expression level of Oct4 following induction of ESC differentiation (14, 18). On the other hand, miR-302 functions to regulate cell cycle regulators CDKN1A and RBL2 (19), TGF-β signaling negative regulator Lefty1/2 (20), and pluripotency factors Oct4 and Sox2 (21) and thereby contributes to the maintenance of ESC pluripotency. Recent studies show that ectopic expression of miR-302 can promote somatic cell reprogramming (22, 23). Moreover, introduction of a combination of miR-302 with miR-200c and miR-369 can efficiently induce mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotent stage (24), demonstrating that miR-302 not only plays a critical regulatory role in pluripotency maintenance but also contributes to somatic cell reprogramming.

In light of the pivotal role of miR-302 in the maintenance of pluripotency and the cell reprogramming process, we screened for potential chemicals to manipulate miR-302 expression. We found that tranilast, an anti-allergy drug, can significantly up-regulate miR-302 by activating AhR. Moreover, tranilast and other AhR agonists can promote somatic cell reprogramming in a miR-302-dependent way.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Derivation of Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast (MEF) Cells

MEF cells were isolated from e13.5 embryos heterozygous for the Oct4::GFP transgenic allele as described previously (9). Gonads and internal organs were removed when the embryos were processed for isolation of MEF cells. MEF cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mm GlutaMAX, 0.1 mm nonessential amino acids, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Isolated MEF cells (MEFs) in early passages (up to passage 2) were used for further experiments.

Mouse ESC Culture

Feeder-free E14 stem cells were grown on gelatin-coated dishes and cultured in mouse ESC culture medium consisting of DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 2 mm GlutaMAX, 0.1 mm nonessential amino acids, 0.1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 1000 units/ml LIF, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. To detect the role of AhR and tranilast on the maintenance of the pluripotency of E14 stem cells, E14 stem cells were infected with AhR lentivirus or miR-302 antagomirs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the instructions of the manufacturer; the cells were then treated with tranilast and cultured in mouse ESC culture medium with LIF or without LIF for 4 days. For pluripotency gene analysis, cells were harvested for RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR. Cells were stained for alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity with an alkaline phosphatase detection kit (Sigma).

Mouse iPSC Generation

Retroviruses were produced by transfection of plat-E cells with pMXs retroviral vectors containing the coding sequences of mouse Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4. MEFs (passages 1 and 2) were seeded at a density of 200,000 cells/well in 6-well plates 18 h before infection. Supernatants containing the three retroviruses were mixed and incubated with MEF cells. Two days post-virus infection, transduced MEF cells were split onto feeders in 96-well plates at a density of 5000 cells/well in mES medium (DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 2 mm GlutaMAX, 0.1 mm nonessential amino acids, 0.1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 1000 units/ml LIF, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin). At day 6, the culture medium was replaced with KSR medium (knock-out DMEM supplemented with 15% knock-out serum replacement, 2 mm GlutaMAX, 0.1 mm nonessential amino acids, 0.1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 1000 units/ml LIF, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin).

Plasmid Construction

The different regions of miR-302 promoter were amplified from mouse genomic DNA using primers listed in supplemental Table S3 and inserted into the pGL3-Basic vector. They were named pGL3-349, pGL3-653, pGL3-872, pGL3-1132, pGL3-2049, pGL3-3344, pGL3-3974, pGL3-4364, and pGL3-4746 according to the length of miR-302 promoter carried. The short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) targeting mouse AhR mRNA and the control shRNA were cloned into the pMKO.1 retroviral vector, which was obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). The sequences for the shRNA targeting mouse AhR and for the control shRNA are shown in supplemental Table S4.

Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay

2 μg of miR-302 promoter-reporter and 0.1 μg of Renilla luciferase construct were co-transfected into 6 million HEK293 MSR cells; 12 h later, transfected HEK293 MSR cells were split into 96-well plates at a density of 40,000 cells/well, and chemicals were added. Dual-Luciferase activities were measured 24 h later using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega).

Alkaline Phosphatase and Immunofluorescent Staining

Prior to staining, the iPS cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 min. The AP staining was performed using alkaline phosphatase kits (Sigma, catalogue No. 85L3R) following the manufacturer's protocol. Images were acquired using Zeiss Observer Z1. For immunofluorescent staining, fixed iPS cells were incubated with primary antibodies against mouse SSEA-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-21702) and rabbit Nanog (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-33760) followed by the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to Cy3. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were acquired using the Zeiss LSM 710 system.

FACS Analysis

GFP+ colonies at day 14 were trypsinized and then analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). GFP+ cells were gated with a control signal from the phycoerythrin channel, and a minimum of 10,000 events were recorded.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma). For quantitative mRNA and pri-miRNA analysis, RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). For the real-time quantitative PCR analysis, 2× PCR mix (Sigma) and EvaGreen dye (Biotium, Inc.) were used, with a Stratagene Mx3000P PCR machine. The relative expression values were normalized against the inner control. Primer sequences for this section are listed in supplemental Table S3. For mature miRNAs, real-time quantitative PCR was performed either by using TaqMan miRNA assays (Applied Biosystems) or by designed stem-loop primers as described previously (25). The relative expression values were normalized against the inner control, sno-202 (Applied Biosystems).

Western Blot

Cell lysates were extracted, separated on SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Primary antibodies were as follows: rabbit anti-AhR mouse (1:2000, Biomol) and rabbit anti-β-actin (1:1000, Sigma). The membrane was detected by secondary antibody conjugated to a CW800 fluorescent probe (Rockland) using an infrared imaging system (Odyssey, LI-COR).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assays

ChIP assays were performed as described previously (17, 26). 2 × 106 MEF cells were treated with 100 μm tranilast for 2 h prior to cross-linking for 10 min with 1% formaldehyde. Soluble chromatin was prepared from MEF cells following sonication and centrifugation and then was incubated with anti-AhR antibody (BML-SA210, Biomol), anti-oct4 antibody (Sc-9081, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or rabbit IgG. The primer sequences used for PCR analysis are listed in supplemental Table S3.

Introduction of miRNA Antagomirs

Mir-302 antagomirs (RiboBio) were transfected into MEF cells at day 2 and day 6 or into E14 stem cells immediately using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the instructions of the manufacturer. The oligonucleotide concentration was 50 nm, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 12 h before the medium was changed.

RESULTS

Tranilast Promotes miR-302 Expression

MiR-302 has been shown to regulate pluripotency-controlled genes and contribute to somatic cell reprogramming (27). Cell reprogramming can be promoted by chemicals including histone deacetylation inhibitors, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) inhibitors, TGF-β inhibitors, and others (9, 11, 28, 29). To test whether miR-302 expression is mediated by these reprogramming-related pathways, we generated a series of luciferase reporter constructs carrying different length of miR-302 promoter. All miR-302 promoter-reporters showed significantly higher activity than the control empty pGL3 vector in mESCs (Fig. 1A). The luciferase reporter containing mouse miR-302 promoter spanning base pairs −2049 to +1(relative to predicted transcription start site) (pGL3-2049) showed the highest activity, which is ∼60-fold greater than control empty pGL3 vector. Overexpression of Oct4 and Sox2 further increased the luciferase activity of pGL3-2049 by ∼3-fold in HEK293 MSR cells (Fig. 1B). Consistently, we observed that the expression level of endogenous miR-302 in MEF cells was significantly lower than that in ES cells (15, 30) and could be increased in the presence of Oct4 and Sox2 (Fig. 1B). We monitored pGL3-2049 luciferase reporter activities in cells treated with inhibitors of histone deacetylase, GSK-3β inhibitors, TGF-β inhibitors, and other reported reprogramming-promoting chemicals. We found that the GSK-3β inhibitor IX increased pGL3-2049 activity ∼2 fold, whereas a TGF-β inhibitor, tranilast (N-[3,4-dimethoxycinnamoyl]-anthranilic acid; Rizaben®), increased pGL3-2049 activity by ∼4–5 fold (Fig. 1C). Consistent with what we observed in the luciferase reporter assay, tranilast increased endogenous miR-302c by ∼4-fold in MEF cells (Fig. 1D). Further, tranilast promoted miR-302 promoter-reporter activity and expression of endogenous miR-302 in a dose-dependent manner with a maximum response at 100 μm in MEF cells (Fig. 2, A and B) as well as in the ES cell line E14 (Fig. 2D). The expression of another pluripotency-related miRNA (miR-17–92) was not altered following treatment with tranilast (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that tranilast can promote the expression of miR-302.

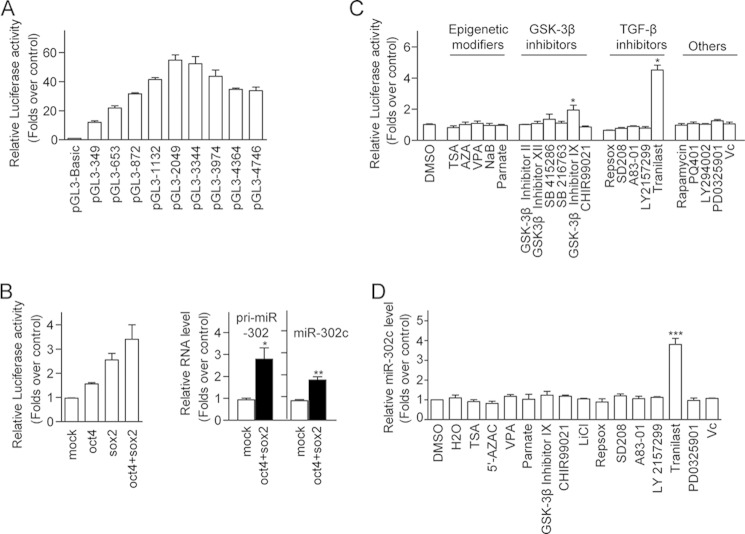

FIGURE 1.

Screening chemicals that can promote miR-302 expression. A, luciferase reporter activities with different lengths of miR-302 promoter in mES cells. E14 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs carrying different lengths of miR-302 promoter. 36 h after transfection, the cells were harvested, and the luciferase activities were monitored. The luciferase reporter activities were compared with pGL3-Basic-transfected cells and are shown. B, overexpression of Oct4 and Sox2 increases miR-302 promoter-reporter activities and endogenous miR-302 expression level. HEK293 MSR cells transfected with the miR-302 promoter reporter constructs, along with Oct4 and Sox2, were assayed for luciferase activities. MEF cells were transfected with Oct4 and Sox2, and the levels of endogenous miR-302 precursor (pri-miR-302) and mature miR-302c were measured. C, tranilast, but not other reprogramming-promoting chemicals, activated transcription of the miR-302 gene. HEK293 MSR cells transfected with miR-302 promoter-reporter constructs are treated with epigenetic modifiers, GSK-3β inhibitors, TGF-β inhibitors, and other iPS-promoting chemicals at concentrations listed in supplemental Table S2. The luciferase reporter activities were compared with DMSO-treated control cells and are shown. D, expression of miR-302c is up-regulated by tranilast in MEF cells. MEF cells were treated with reprogramming-promoting chemicals at concentrations listed in supplemental Table S2 for 24 h, and the miR-302c levels were monitored by real-time quantitative PCR coupled with reverse transcription. The relative miR-302c levels compared with sno-202 snRNA were shown. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; versus control.

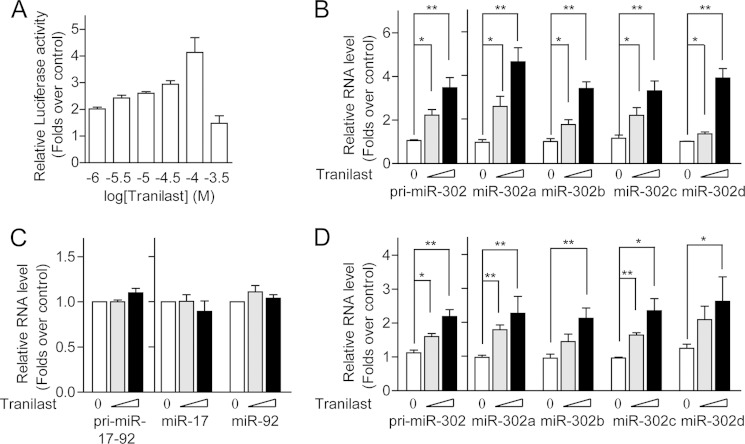

FIGURE 2.

Tranilast promotes miR-302 expression in a dose-dependent manner. A and B, activation of miR-302 expression by tranilast is dose-dependent. MEF cells were treated with different concentrations of tranilast (30 and 100 μm), and the activity of the miR-302 promoter-reporter pGL3-2049 (A) and levels of endogenous miR-302 precursor, pri-miR-302, and mature miR-302 (B) were measured. C, tranilast does not influence endogenous miR-17–92 expression in MEF cells. MEF cells were treated with different concentrations of tranilast (30 and 100 μm), and the levels of endogenous miR-17−92 were measured. D, tranilast enhances miR-302 expression in E14 cells. E14 cells were treated with different concentrations of tranilast (30 and 100 μm), and the levels of endogenous miR-302 precursor, pri-miR-302, and mature miR-302 were measured. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; versus DMSO-treated cells.

Tranilast Regulates miR-302 through Binding of AhR to the AhRE Motif

The putative transcription factor-binding elements in the miR-302 promoter region were predicted using the MatInspector promoter analysis tool (31). MatInspector accurately identified the known Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and Smad binding sites in the miR-302 promoter (Fig. 3A, upper panel). It is of note that the luciferase activities of reporters carrying miR-302 promoter region shorter than 653 bp were not enhanced by tranilast treatment (Fig. 3A), although all truncated miR-302 promoter-reporters showed significantly higher activity than the pGL3-Basic control reporter in ES cells (Fig. 1A), indicating that the promoter region −4364 to −653 bp should be important for tranilast-induced miR-302 expression. We noted that pGL3-653 contains a Smad binding site. It is widely accepted that inhibition of the TGF-β pathway leads to the activation of Smad-controlled gene expression (32). However, the Smad-binding site in the miR-302 promoter did not respond to tranilast treatment (Fig. 3A), suggesting an unknown regulatory mechanism of tranilast other than inhibition of TGF-β pathway. On the other hand, in the promoter region from −4364 to −653 bp, there are three putative AhR binding sites (AhRE1 −3928 to −3904 bp, AhRE2 −1927 to −1903 bp, and AhRE3 −696 to −672 bp). To test whether these three AhREs are responsible for the tranilast-induced miR-302 expression, we further generated a serial mutant reporter constructs. As shown in Fig. 3B, the miR-302 promoter reporter harboring AhRE2 and AhRE3 is as active as the wild type miR-302 promoter reporter following tranilast treatment. Consistently, mutation of either AhRE2 or AhRE3 but not AhRE1 reduced the tranilast-induced luciferase activities. These data suggest that AhRE2 and AhRE3 are essential for the up-regulation of miR-302 expression in response to tranilast treatment.

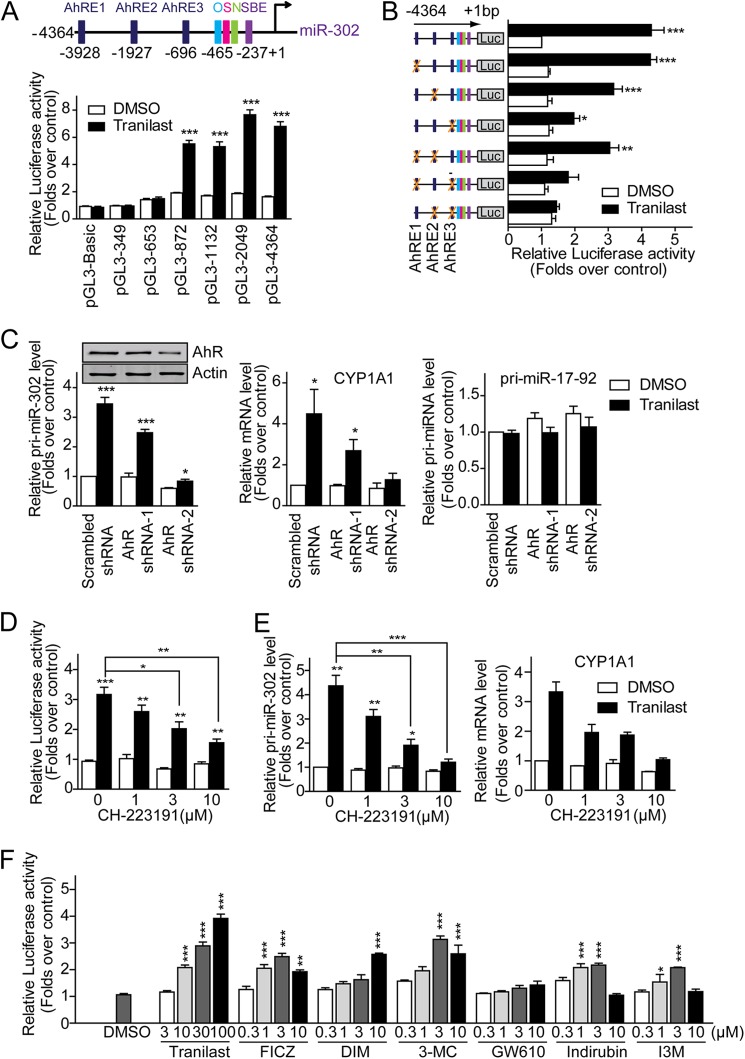

FIGURE 3.

Tranilast promotes miR-302 expression via AhR. A, luciferase reporter activities with different lengths of miR-302 promoter. Top, schematic representation of the promoter region of miR-302. Bottom, HEK293 MSR cells transfected with luciferase reporter constructs carrying different lengths of miR-302 promoter. After treatment with tranilast (100 μm) for 24 h, the cells were harvested and luciferase activities were monitored. B, luciferase reporter activities with different mutants of miR-302 promoter. A schematic illustration of mutant constructs of miR-302 promoter-reporter is presented. C, knockdown of AhR expression inhibits tranilast-induced miR-302 expression. MEF cells were infected with pseudo retroviruses carrying either scrambled control shRNA or AhR-specific shRNA. 72 h after infection, cellular AhR levels were monitored on Western blots and are shown. Pri-miR-302, Pri-miR-17-92, and CYP1A1 expression levels were assayed in these MEFs treated with tranilast. D and E, blockage of tranilast-induced miR-302 expression by AhR antagonist. MEF cells were treated with different concentrations of the AhR antagonist CH-223191 in the absence or presence of tranilast, and the activities of miR-302 promoter-reporter pGL3-2049 (D) and levels of the endogenous miR-302 precursor, pri-miR-302, and CYP1A1 (E) were measured. F, AhR agonists up-regulate miR-302 promoter-reporter activities. HEK293 MSR cells transfected with miR-302 promoter-reporter constructs are treated with AhR agonists at the indicated concentrations. The luciferase reporter activities were compared with DMSO-treated control cells and are shown. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; versus DMSO-treated cells.

Studies have shown that tranilast also acts as an agonist of AhR (33). AhR is a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor. By binding to the AhREs, AhR mediates diverse gene expression and plays an important role in different cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, cell adhesion, and organ homeostasis (34, 35). Given that tranilast-promoted miR-302 expression depends on AhREs in the miR-302 promoter, we hypothesized that tranilast enhances miR-302 expression through activation of AhR. Indeed, although the endogenous AhR level in MEF cells was knocked down by AhR shRNA retrovirus, tranilast-induced miR-302 expression (Fig. 3C), as well as the AhR downstream gene CYP1A1, was significantly reduced. The expression level of pri-miR-17–92 was not changed upon knockdown of AhR. Moreover, in the presence of the AhR antagonist CH-223191, tranilast-mediated miR-302 promoter-reporter activity and expression of endogenous miR-302 (Fig. 3, D and E), as well as CYP1A1, were significantly blocked. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3F, all AhR agonists we tested enhanced the miR-302 promoter-reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner. The reported EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) values of these AhR agonists to activate AhR are listed in supplemental Table S1. These data indicate that activation of AhR positively regulates miR-302 expression.

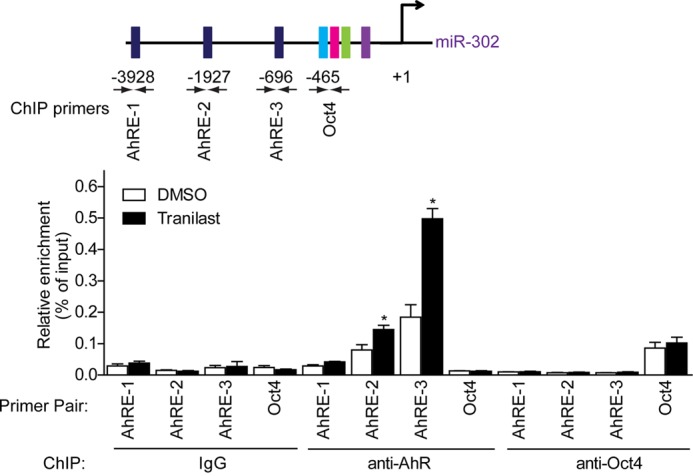

To test whether AhR was directly recruited to AhREs upon tranilast treatment, we then performed a ChIP assay. DNA fragments associated with immunopurified AhR or Oct4 were analyzed by quantitative PCR (Fig. 4A). A considerable amount of endogenous Oct4 and AhR was bound to the promoter region of miR-302. The presence of AhR on AhRE2 and AhRE3 but not AhRE1 was significantly enhanced following tranilast treatment. On the other hand, the occupancy of Oct4 on miR-302 had not been altered by tranilast treatment. Together, these results demonstrated that binding of activated AhR to the AhREs on miR-302 promoter is required for tranilast-induced miR-302 expression.

FIGURE 4.

Tranilast activates AhR binding to AhRE2 and AhRE3 on the miR-302 promoter. MEF cells were stimulated with tranilast for 2 h and subjected to a ChIP assay using anti-AhR, anti-Oct4, and anti-IgG antibodies. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR, and the relative enrichments are presented as a percentage of the input DNA. A schematic illustration of primer pairs used for quantitative PCR is shown. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, versus DMSO-treated cells.

Sustaining miR-302 Expression by AhR and Tranilast Supports Pluripotency of Mouse ES Cells

It is known that expression of miR-302 activates pluripotent genes and contributes to the maintenance of pluripotency (36); thus we tested whether AhR mediates ES cell pluripotency through miR-302. We knocked down AhR expression in mouse E14 cells using AhR shRNA lentivirus. As shown in Fig. 5A, the expression of primary and mature miR-302 was significantly reduced following AhR shRNA lentivirus infection. Four days after infection, the self-renewal status of these cells was determined by morphology and the AP staining assay as well as the expression of pluripotency markers and differentiation genes. We found a reduction of AhR impaired the colony morphology with decreased AP activity (Fig. 5B), reduced pluripotency gene (Nanog and Rex1) expression, and increased the level of differentiation markers (Fgf5, Gata4, and Tbx5) (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that knockdown of AhR leads to reduced miR-302 expression and ESC pluripotency.

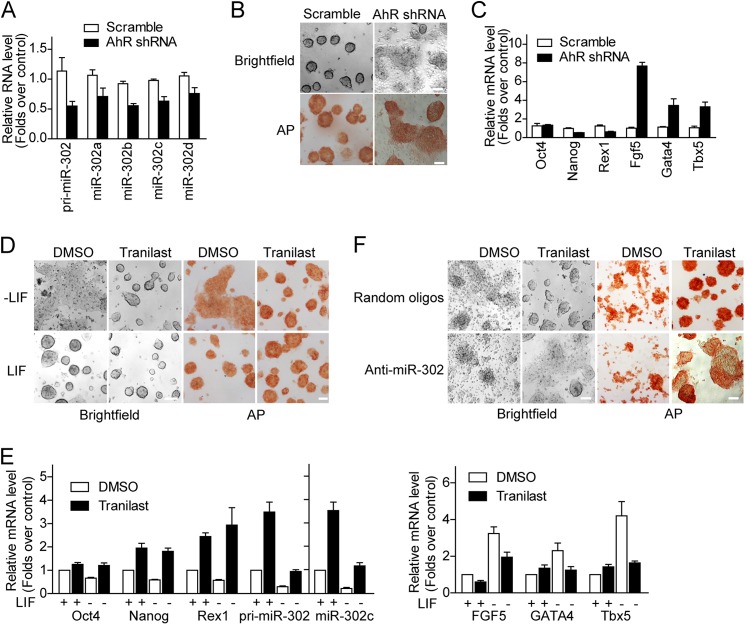

FIGURE 5.

Sustaining miR-302 expression by AhR and tranilast supports pluripotency of mouse ES cells. A, knockdown of AhR inhibits miR-302 expression. E14 cells were infected with scrambled control shRNA or AhR-specific shRNA lentivirus for 2 days. Levels of endogenous miR-302 precursor (pri-miR-302) and matured miR-302 were measured. B, silencing AhR results in morphological changes and loss of AP staining in ESCs. E14 cells were infected with the indicated shRNAs and cultured in mouse ESC medium. Cells were stained with the AP staining kit and imaged 4 days after infection. C, AhR silencing leads to down-regulation of pluripotency genes and up-regulation of differentiation markers. E14 cells were infected with the indicated shRNAs and cultured in mouse ESC medium. Cells were harvested for quantitative real-time PCR analysis 4 days after infection. D, representative images of morphology and AP staining in E14 cells, which were cultured for 4 days in mouse ESC medium with or without LIF or tranilast as indicated. E, tranilast promotes pluripotency genes and inhibits differentiation genes. E14 cells cultured as described in D were harvested for quantitative real-time PCR analysis. F, representative images of morphology and AP staining in E14 cells, which were infected with miR-302 antagomirs and cultured in mouse ESC medium without LIF for 4 days. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E. Scale bars = 100 μm.

LIF is an essential supplement in culture medium for E14 stem cells and maintains the pluripotency of E14 cells. Under this normal culture condition, E14 cells treated with tranilast showed similar colony morphology and AP activity but higher pluripotency gene expression levels compared with that of mock-treated cells (Fig. 5, D and E). When cultured without LIF, E14 cells lost colony morphology with decreased AP activity, reduced pluripotency gene expression, and an increased level of differentiation markers (Fig. 5, D and E). Interestingly, in the presence of tranilast, E14 cell cultured in the absence of LIF showed colony morphology, higher AP activity, and expression of both pluripotency genes and miR-302. These data indicate that tranilast can help to maintain pluripotency of mouse ES cells.

Further more, blocking the function of miR-302 by miR-302 antagomirs abolished the pluripotency-supporting function of tranilast on E14 cells under differentiation condition (Fig. 5F). Together, these results indicate that tranilast sustains miR-302 expression and supports mouse ES cell pluripotency.

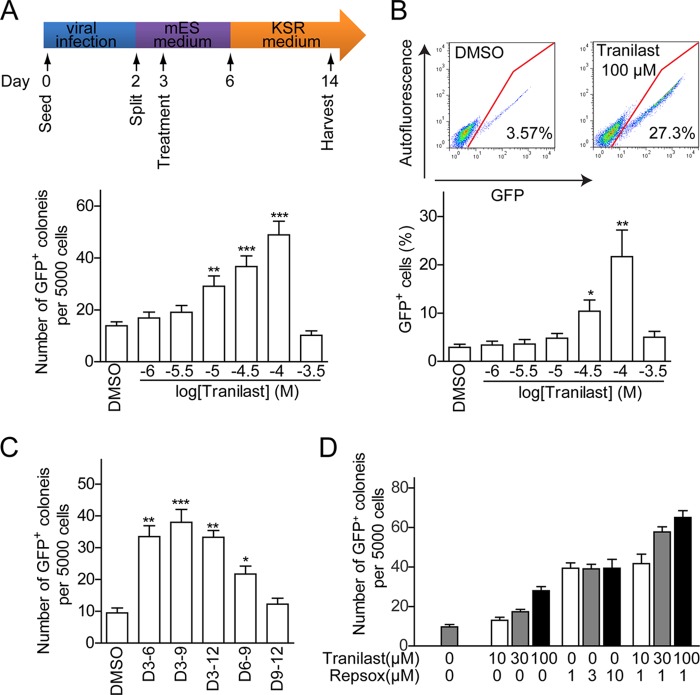

Tranilast Promotes Cell Reprogramming through AhR-mediated miR-302 Expression

Studies show that expression of miR-302 facilitates somatic cell reprogramming (21–24). We then tested whether tranilast could promote iPSCs generation through miR-302. Two days after the retroviral transduction of three vectors that express Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (OSK), primary MEFs derived from OG2+/−/ROSA26+/− (OG2) mice (containing a transgenic Oct4-GFP reporter) were seeded onto feeder cells in 96-well plates in mouse ESC culture medium; this was designated as day 2. These MEFs were treated with different concentration of tranilast from day 3 to day 9 as indicated in Fig. 6A, upper panel. At day 14 post-infection, we observed the appearance of morphological ES-like and GFP+ colonies. Tranilast treatment increased the number of GFP+ colonies in a dose-dependent manner. The treatment with 100 μm tranilast increased the number of GFP+ colonies by ∼ 3-fold (Fig. 6A). FACS analysis of OSK-infected OG2 MEFs at day 14 post-infection displayed a >7-fold increase of GFP+ cells in samples treated with 100 μm tranilast (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, we found that the treatment of MEFs with tranilast following day 3 post-infection exhibited prominent reprogramming-enhancing effects (Fig. 6C), suggesting that tranilast promotes the reprogramming process at the initial stage. Interestingly, a combined treatment using tranilast with the iPS-promoting TGF-β inhibitor RepSox led to an ∼2-fold increase in the reprogramming efficiency of the OSK-infected MEFs compared with tranilast or RepSox treatment alone (Fig. 6D). This synergetic effect of tranilast with RepSox on cell reprogramming suggests that although tranilast shows an inhibitory effect on TGF-β signaling (37), it is less possible that tranilast promotes reprogramming through inhibition of the TGF-β pathway. Further, we found that tranilast also promoted single-factor Oct4-induced reprogramming in the presence of VPA, CHIR99021, parnate, and RepSox by ∼2-fold (data not shown). Together, these results indicate that tranilast promotes somatic cell reprogramming.

FIGURE 6.

Tranilast promotes cell reprogramming. A and B, tranilast promotes the generation of GFP+ colonies from OSK-infected MEFs. A, top, schematic representation of in vitro cell reprogramming protocol. Bottom, the number of GFP+ colonies generated from tranilast-treated, OSK-infected MEFs. B, the percentage of GFP+ cells was determined by FACS analysis at day 14. Top, representative FACS data demonstrate an increase in the percentage of GFP+ cells after treatment of 100 μm tranilast. Bottom, the percentages of GFP+ cells that were induced in OSK-infected MEFs treated with different concentrations of tranilast. C, tranilast promotes cell reprogramming at the early stage. OSK-infected MEFs were treated with 100 μm tranilast for various durations as indicated, and GFP+ colonies were counted at day 14. D, enhancement of iPSC generation by tranilast and RepSox. OG2 MEF cells infected with OSK plus tranilast or RepSox at the indicated concentrations were added to the culture medium on days 3–9. GFP+ colonies were counted at day 14. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001 versus DMSO-treated cells.

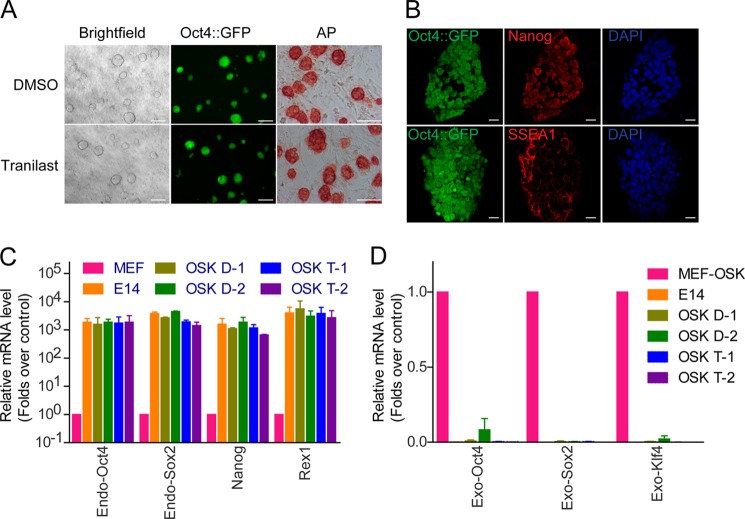

To further evaluate the pluripotency of the iPSCs generated by tranilast treatment, we picked colonies randomly from the culture of tranilast-treated OSK-infected MEFs and established multiple iPSC lines. All of these lines were morphologically indistinguishable from mouse ES cells, and they stained positive for alkaline phosphatase (Fig. 7A). A randomly chosen clone was then subjected to further immunofluorescent analysis. These cells expressed high levels of the pluripotency markers SSEA1 and Nanog (Fig. 7B).The endogenous expression of Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog, as well as the silencing of exogenous retroviral factors expression, was verified by real-time quantitative PCR (Fig. 7, C and D). These results suggest that tranilast treatment does not compromise iPSC pluripotency.

FIGURE 7.

Tranilast-promoted iPSCs are pluripotent. A, representative pictures of the iPSCs generated in the presence of tranilast. Left, phase contrast; middle, Oct4::GFP; right, AP staining. Scale bars = 100 μm. B, the iPSCs generated in the presence of tranilast express typical pluripotency markers. The representative picture of Oct4::GFP expression and immunofluorescent staining of pluripotency genes SSEA-1 and Nanog are shown. Scale bars = 20 μm. C, the relative gene expression of endogenous pluripotency markers in established iPSC lines. D, the silencing of viral transgenes expression. Quantitative PCR analysis of pluripotency genes and exogenous transgenes in two OSK-iPS clones and two OSK-iPS clones generated with tranilast treatment. mES cell line E14, MEF, and OSK-infected MEF at 4 days (MEF-OSK) were used as controls. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E.

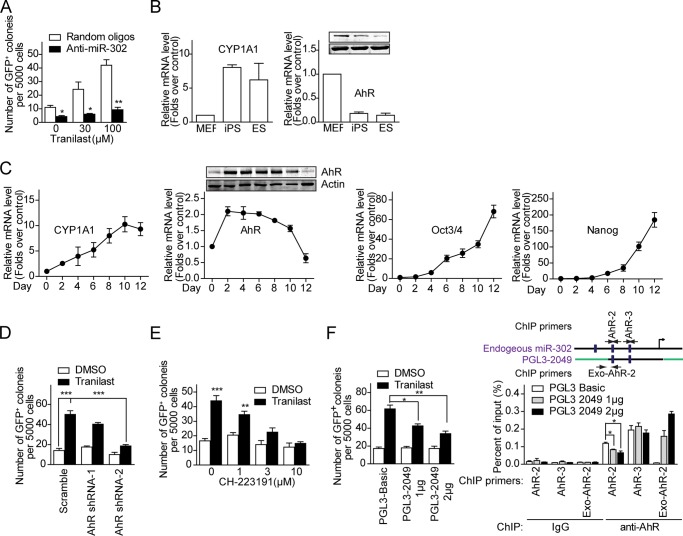

To test whether the promotion of iPSC generation by tranilast depends on miR-302, OSK-infected OG2 MEF cells were treated with miR-302 antagomirs and examined for reprogramming efficiency. As shown in Fig. 8A, antagomir-mediated silencing of endogenous miR-302 decreased OSK-infected OG2 MEF reprogramming and abolished the reprogramming-enhancing effect of tranilast, demonstrating a requirement for miR-302 in the cell reprogramming progress.

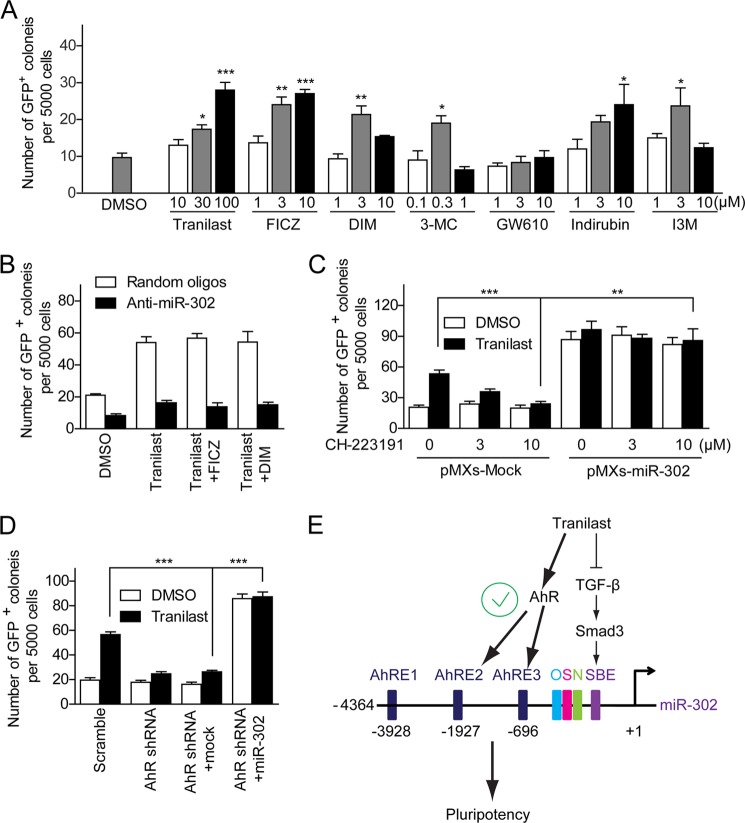

FIGURE 8.

Impairment of AhR-mediated miR-302 expression inhibits tranilast-promoted cell reprogramming. A, blockage of tranilast-promoted cell reprogramming by miR-302 antagomirs. Antagomirs were transfected into OSK-infected MEF cells at day 2 and day 6. Tranilast was added to the culture medium on days 3–9. B, AhR is activated in ES cells and iPS cells. Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis of the AhR downstream gene CYP1A1 and AhR expression in MEFs, iPS cells, and mES cells. C, quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis of CYP1A1, AhR, Oct4, and Nanog expression on the indicated days in OSK-transduced MEF cells. D, knockdown of AhR reduces tranilast-promoted iPSC generation. MEF cells were infected with OSK together with scrambled control shRNA or AhR-specific shRNA. Tranilast was added to the culture medium on days 3–9. E, blockage of tranilast-induced cell reprogramming by AhR antagonist. Tranilast and AhR antagonist CH-223191 at the indicated concentrations were added to the culture medium of OSK-infected MEFs on days 3–9. F, interruption of AhR binding to the promoter of miR-302 blocks tranilast-induced cell reprogramming. MEF cells were infected with OSK together with pGL3-Basic and pGL3-2049. Tranilast was added to the culture medium on days 3–9. Left, the number of GFP+ colonies generated from tranilast-treated, OSK-infected MEFs is shown. Right, occupation of AhR on miR-302 promoters presented on either pGL3-2049 or miR-302 gene. MEF cells at day 3 were subjected to ChIP assay using anti-AhR and anti-IgG antibodies. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR, and the relative enrichments are presented as a percentage of the input DNA. A schematic illustration of primer pairs used for quantitative PCR is shown. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; versus control.

We have shown that tranilast treatment led to binding of AhR to AhREs in miR-302 promoter and thereby enhanced expression of miR-302. To assess the involvement of AhR involved in the cell reprogramming process, we examined the expression levels of AhR and the AhR downstream gene CYP1A1 in MEFs, iPS cells, and mES cells. As shown in Fig. 8B, although AhR was expressed at low level in iPS cells and mES cells compared with MEFs, the high expression level of CYP1A1 in iPS cells and mES cells suggested an activation of AhR-mediated gene expression in iPS cells and mES cells. To further clarify the activation of AhR during reprogramming, we examined the expression levels of CYP1A1 and AhR at different time point during reprogramming (Fig. 8C). The dynamic increase of the pluripotent genes Oct4 and Nanog indicated successful reprogramming. We found the expression level of AhR was increased at day 2 post-virus infection and then gradually decreased by half by day 12 compared with MEFs. Interestingly, CYP1A1 gradually increased with the reprogramming process, which suggested that AhR was activated during the reprogramming process and that activation of AhR may facilitate cell reprogramming.

We then tested whether the reprogramming-enhancing effect of tranilast was due to its activation of miR-302 expression by AhR. OSK-infected OG2 MEFs were treated with AhR shRNA or different doses of the AhR antagonist CH-223191 in the absence or presence of tranilast from day 3 to day 9 post-infection, and the number of GFP+ colonies with ES cell-like morphology was counted at day 14. As shown in Fig. 8, D and E, we observed a robust inhibition of the appearance of tranilast-promoted GFP+ colonies by AhR shRNA or the AhR antagonist CH-223191, demonstrating that expression and activation of AhR is required for tranilast-promoted cell reprogramming. Further, the tranilast-promoted cell reprogramming could be reduced significantly in the presence of the miR-302 promoter reporter pGL3-2049 (Fig. 8F, left panel), because the ectopic exogenous miR-302 promoter on the reporter constructs competed with the endogenous miR-302 promoter for AhR binding as shown in the ChIP experiment (Fig. 8F, right panel).

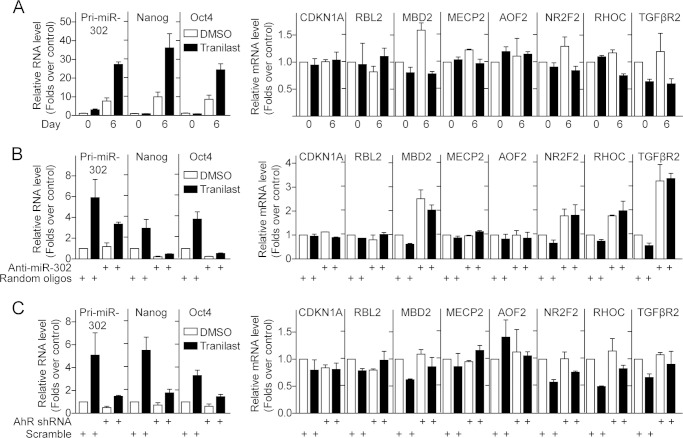

Tranilast treatment not only leads to activation of miR-302 expression but also increases expression of the pluripotent genes Oct4 and Nanog during cell reprogramming (Fig. 9A). The miR-302 target genes including MBD2, NF2R2, RHOC, and TGFβ2R were also down-regulated by tranilast treatment in these OSK-infected MEFs (Fig. 9A). In the presence of miR-302 antagomirs or AhR shRNA, tranilast could not increase expression of pluripotent genes Oct4 and Nanog or down-regulate miR-302 target genes (Fig. 9, B and C), indicating that tranilast mediates the expression of these genes in a miR-302-dependent manner.

FIGURE 9.

Tranilast down-regulates miR-302 target genes during reprogramming process. A, tranilast treatment up-regulates pluripotent genes and down-regulates miR-302 target genes during reprogramming process. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of expression of pluripotent genes and miR-302 target genes at day 6 after infection with OSK or uninfected MEFs treated with tranilast. B and C, knockdown of miR-302 or AhR diminishes tranilast-mediated expression of pluripotent genes and miR-302 target genes. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of cells harvested 6 days after infection with OSK together with miR-302 antagomirs (B) or AhR shRNA (C). Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E.

Moreover, AhR agonists including FICZ (6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole), DIM (3,3′-diindolylmethane), 3-methylcholanthrene, indirubin, and indirubin-3-monoxime, but not GW610 (2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-5-fluoro-benzothiazole), promoted cell reprogramming to different extents (Fig. 10A). Neither FICZ nor DIM could rescue miR-302 antagomir-blocked cell reprogramming in the presence of tranilast (Fig. 10B). However, supplementing miR-302 expression with retroviruses, on the other hand, efficiently rescued the blockage of tranilast-promoted cell reprogramming by AhR knockdown or AhR antagonist (Fig. 10, C and D). Taken together, these results indicate that activation of AhR-mediated miR-302 expression is beneficial for somatic cell reprogramming (Fig 10E).

FIGURE 10.

Activation of AhR- mediated miR-302 expression promoted cell reprogramming. A, AhR agonists promote cell reprogramming. OSK-infected MEF cells were treated with AhR agonists at the indicated concentrations from days 3–9. B, AhR agonists cannot rescue the blockage of cell reprogramming by miR-302 antagomirs. Antagomirs were transfected into OSK-infected MEF cells at day 2 and day 6. Tranilast and AhR agonists were added to the culture medium on days 3–9. C, supplementing miR-302 expression with retrovirus abolishes the blockage of tranilast-promoted cell reprogramming by AhR knockdown. MEF cells were infected with OSK together with the indicated shRNA and pMXs-miR-302 retrovirus. Tranilast was added to the culture medium on days 3–9. D, supplementing miR-302 expression with retrovirus rescues the blockage of tranilast-promoted cell reprogramming by AhR antagonist. MEF cells were infected with OSK together with pMXs-miR-302 retrovirus. Tranilast and AhR antagonist CH-223191 at the indicated concentrations were added to the culture medium on days 3–9. E, schematic diagram shows that tranilast facilitates cell reprogramming through AhR-mediated miR-302 expression. Data from three independent experiments are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, ***, p < 0.001; versus control.

DISCUSSION

Mouse and human miR-302 orthologs show highly conserved nucleotide sequences and genomic organization (14). MiR-302 is highly expressed in ESCs and has been shown to regulate pluripotency-controlled genes and help somatic cell reprogramming. MiR-302 is expressed at a low level in differentiated cells in general; however, it can be elevated upon specific stimuli or pathological conditions (26, 38). But the mechanisms by which miR-302 is regulated are less well understood. Previous studies show that Oct4 and Sox2 co-occupy the promoter region and regulate expression of miR-302; the expression level of miR-302 correlates well with Oct4 transcript in ESCs and early embryonic development (17, 18, 39). A recent study reports that hyaluronan stimulates the CD44v3 (a hyaluronan receptor) interaction with Oct4-Sox2-Nanog leading to both a complex formation and the nuclear translocation of three transcription factors to promote miR-302 expression, which causes self-renewal, clonal formation, and cisplatin resistance in cancer stem cells from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (40). Another report demonstrates that the BMP4-Smad pathway represses the transcription of miR-302 and derepresses the expression of the type II BMP receptor in vSMCs (26). During the preparation of this paper, Zhang and Wu (41) reported that sodium butyrate promotes the generation of human iPS cells through induction of the miR302/367 cluster. They also found that expression of miR-302 was not up-regulated by the TGF-β inhibitor SB431542, which also supports our finding that tranilast up-regulates miR-302 expression through activation of AhR instead of inhibition of the TGF-β pathway. Activation of AhR by tranilast leads to the binding of AhR to the miR-302 promoter and thereby promotes miR-302 expression and enhances cell reprogramming. Thus, our study not only elucidates a novel regulatory mechanism of miR-302 expression but also provides a strategy for promoting somatic cell reprogramming by AhR ligands.

AhR belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family (42). Recently reports show that tryptophan metabolites, indole-containing structures, 7-ketocholesterol, and prostaglandins, function as ligands of AhR (43). AhR mediates cellular responses to environmental toxins (44). Besides, AhR has been shown to regulate cellular responses to oxidative stress and inflammation by mediating the transcription level of genes involved in the signaling of Nrf2 (45), p53 (46), RB1 (44), and NF-κB (47). AhR also has an important function in many developmental pathways, including hematopoiesis (48), lymphoid systems (49), T-cells (50, 51), neurons (52), and hepatocytes (53, 54). In this study, we found that AhR is gradually activated during cell reprogramming and is highly activated in iPS cells and mES cells compared with MEFs. There are three AhREs in the miR-302 promoter, and activation of AhR by tranilast can promote miR-302 expression and cell reprogramming. Moreover, we found that some other AhR agonists could also enhance iPSC generation by promoting miR-302 expression, suggesting an important role for AhR in cell reprogramming. Nevertheless, whether AhR-mediated miR-302 expression is also involved in other physiologic functions of AhR should be explored.

Tranilast is an anti-allergy, over-the-counter drug used against asthma, autoimmune diseases, and atopic and fibrotic pathologies. Tranilast inhibits the growth and metastasis of mammary carcinoma (55). The antiproliferative potential of tranilast depends principally on the capacity of tranilast to interfere with TGF-β signaling through inhibiting TGF-β release (56). Although there is a Smad binding site on the miR-302 promoter, our study shows that induction of miR-302 by tranilast probably does not occur via the TGF-β/Smad pathway. Furthermore, tranilast and RepSox, a TGF-β inhibitor, synergistically promote iPSC generation, suggesting that tranilast does not function as an inhibitor of the TGF-β pathway in cell reprogramming process. The cell reprogramming process can be divided into three phases, namely initiation, maturation, and stabilization. Some reports have shown that histone deacetylase inhibitor and TGF-β inhibitors function at the initiation stage of reprogramming, whereas MEK inhibitors function at the maturation and stabilization phase (29, 57, 58). Our study shows that tranilast functions at the initial stage of reprogramming, suggesting that activation of AhR-mediated miR-302 expression might facilitate the bypass of certain reprogramming barriers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Duanqing Pei (Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health) for the pMXs-miR-302 plasmid. We also thank all members of our laboratory for sharing reagents and advice.

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA01010302) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (2011CB910202 and 2009CB940903).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S4.

- iPSC

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- AhR

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AP

- alkaline phosphatase

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- MiR-302

- microRNA-302-367 cluster

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- OSK

- Oct4/Sox2/Klf4

- LIF

- leukemia inhibitory factor

- MSR

- macrophage scavenger receptor

- AhRE

- aryl hydrocarbon-responsive element.

REFERENCES

- 1. Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okita K., Ichisaka T., Yamanaka S. (2007) Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 448, 313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu J., Vodyanik M. A., Smuga-Otto K., Antosiewicz-Bourget J., Frane J. L., Tian S., Nie J., Jonsdottir G. A., Ruotti V., Stewart R., Slukvin II, Thomson J. A. (2007) Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim J. B., Sebastiano V., Wu G., Araúzo-Bravo M. J., Sasse P., Gentile L., Ko K., Ruau D., Ehrich M., van den Boom D., Meyer J., Hübner K., Bernemann C., Ortmeier C., Zenke M., Fleischmann B. K., Zaehres H., Schöler H. R. (2009) Oct4-induced pluripotency in adult neural stem cells. Cell 136, 411–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gonzalez F., Barragan Monasterio M., Tiscornia G., Montserrat Pulido N., Vassena R., Batlle Morera L., Rodriguez Piza I., Izpisua Belmonte J. C. (2009) Generation of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells by transient expression of a single nonviral polycistronic vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8918–8922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim D., Kim C. H., Moon J. I., Chung Y. G., Chang M. Y., Han B. S., Ko S., Yang E., Cha K. Y., Lanza R., Kim K. S. (2009) Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell 4, 472–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muraro M. J., Kempe H., Verschure P. J. (2013) The dynamics of induced pluripotency and its behavior captured in gene network motifs. Stem Cells 31, 838–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morris S. A., Daley G. Q. (2013) A blueprint for engineering cell fate: current technologies to reprogram cell identity. Cell Res 23, 33–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huangfu D., Maehr R., Guo W., Eijkelenboom A., Snitow M., Chen A. E., Melton D. A. (2008) Induction of pluripotent stem cells by defined factors is greatly improved by small-molecule compounds. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 795–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carey B. W., Markoulaki S., Hanna J., Saha K., Gao Q., Mitalipova M., Jaenisch R. (2009) Reprogramming of murine and human somatic cells using a single polycistronic vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 157–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ichida J. K., Blanchard J., Lam K., Son E. Y., Chung J. E., Egli D., Loh K. M., Carter A. C., Di Giorgio F. P., Koszka K., Huangfu D., Akutsu H., Liu D. R., Rubin L. L., Eggan K. (2009) A small-molecule inhibitor of TGF-β signaling replaces Sox2 in reprogramming by inducing Nanog. Cell Stem Cell 5, 491–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Esteban M. A., Wang T., Qin B., Yang J., Qin D., Cai J., Li W., Weng Z., Chen J., Ni S., Chen K., Li Y., Liu X., Xu J., Zhang S., Li F., He W., Labuda K., Song Y., Peterbauer A., Wolbank S., Redl H., Zhong M., Cai D., Zeng L., Pei D. (2010) Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6, 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen T., Shen L., Yu J., Wan H., Guo A., Chen J., Long Y., Zhao J., Pei G. (2011) Rapamycin and other longevity-promoting compounds enhance the generation of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells. Aging Cell 10, 908–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barroso-delJesus A., Romero-López C., Lucena-Aguilar G., Melen G. J., Sanchez L., Ligero G., Berzal-Herranz A., Menendez P. (2008) Embryonic stem cell-specific miR302–367 cluster: human gene structure and functional characterization of its core promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 6609–6619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Houbaviy H. B., Murray M. F., Sharp P. A. (2003) Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs. Dev. Cell 5, 351–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suh M. R., Lee Y., Kim J. Y., Kim S. K., Moon S. H., Lee J. Y., Cha K. Y., Chung H. M., Yoon H. S., Moon S. Y., Kim V. N., Kim K. S. (2004) Human embryonic stem cells express a unique set of microRNAs. Dev. Biol. 270, 488–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Card D. A., Hebbar P. B., Li L., Trotter K. W., Komatsu Y., Mishina Y., Archer T. K. (2008) Oct4/Sox2-regulated miR-302 targets cyclin D1 in human embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 6426–6438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu H., Deng S., Zhao Z., Zhang H., Xiao J., Song W., Gao F., Guan Y. (2011) Oct4 regulates the miR-302 cluster in P19 mouse embryonic carcinoma cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 38, 2155–2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Subramanyam D., Lamouille S., Judson R. L., Liu J. Y., Bucay N., Derynck R., Blelloch R. (2011) Multiple targets of miR-302 and miR-372 promote reprogramming of human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 443–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barroso-delJesus A., Lucena-Aguilar G., Sanchez L., Ligero G., Gutierrez-Aranda I., Menendez P. (2011) The Nodal inhibitor Lefty is negatively modulated by the microRNA miR-302 in human embryonic stem cells. FASEB J. 25, 1497–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu S., Wilson K. D., Ghosh Z., Han L., Wang Y., Lan F., Ransohoff K. J., Burridge P., Wu J. C. (2013) MicroRNA-302 increases reprogramming efficiency via repression of NR2F2. Stem Cells 31, 259–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anokye-Danso F., Trivedi C. M., Juhr D., Gupta M., Cui Z., Tian Y., Zhang Y., Yang W., Gruber P. J., Epstein J. A., Morrisey E. E. (2011) Highly efficient miRNA-mediated reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 8, 376–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liao B., Bao X., Liu L., Feng S., Zovoilis A., Liu W., Xue Y., Cai J., Guo X., Qin B., Zhang R., Wu J., Lai L., Teng M., Niu L., Zhang B., Esteban M. A., Pei D. (2011) MicroRNA cluster 302–367 enhances somatic cell reprogramming by accelerating a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 17359–17364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miyoshi N., Ishii H., Nagano H., Haraguchi N., Dewi D. L., Kano Y., Nishikawa S., Tanemura M., Mimori K., Tanaka F., Saito T., Nishimura J., Takemasa I., Mizushima T., Ikeda M., Yamamoto H., Sekimoto M., Doki Y., Mori M. (2011) Reprogramming of mouse and human cells to pluripotency using mature microRNAs. Cell Stem Cell 8, 633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen C., Ridzon D. A., Broomer A. J., Zhou Z., Lee D. H., Nguyen J. T., Barbisin M., Xu N. L., Mahuvakar V. R., Andersen M. R., Lao K. Q., Livak K. J., Guegler K. J. (2005) Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kang H., Louie J., Weisman A., Sheu-Gruttadauria J., Davis-Dusenbery B. N., Lagna G., Hata A. (2012) Inhibition of microRNA-302 (miR-302) by bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) facilitates the BMP signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 38656–38664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Judson R. L., Babiarz J. E., Venere M., Blelloch R. (2009) Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs promote induced pluripotency. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 459–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shi Y., Desponts C., Do J. T., Hahm H. S., Schöler H. R., Ding S. (2008) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with small-molecule compounds. Cell Stem Cell 3, 568–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shi Y., Do J. T., Desponts C., Hahm H. S., Schöler H. R., Ding S. (2008) A combined chemical and genetic approach for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2, 525–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilson K. D., Venkatasubrahmanyam S., Jia F., Sun N., Butte A. J., Wu J. C. (2009) MicroRNA profiling of human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 18, 749–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cartharius K., Frech K., Grote K., Klocke B., Haltmeier M., Klingenhoff A., Frisch M., Bayerlein M., Werner T. (2005) MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics 21, 2933–2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shi Y., Massagué J. (2003) Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 113, 685–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prud'homme G. J., Glinka Y., Toulina A., Ace O., Subramaniam V., Jothy S. (2010) Breast cancer stem-like cells are inhibited by a non-toxic aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist. PLoS One 5, e13831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Esser C., Rannug A., Stockinger B. (2009) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor in immunity. Trends Immunol. 30, 447–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barouki R., Coumoul X., Fernandez-Salguero P. M. (2007) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor, more than a xenobiotic-interacting protein. FEBS Lett. 581, 3608–3615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lipchina I., Studer L., Betel D. (2012) The expanding role of miR-302–367 in pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell Cycle 11, 1517–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Suzawa H., Kikuchi S., Ichikawa K., Koda A. (1992) Inhibitory action of tranilast, an anti-allergic drug, on the release of cytokines and PGE2 from human monocytes-macrophages. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 60, 85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Murray M. J., Halsall D. J., Hook C. E., Williams D. M., Nicholson J. C., Coleman N. (2011) Identification of microRNAs From the miR-371–373 and miR-302 clusters as potential serum biomarkers of malignant germ cell tumors. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 135, 119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marson A., Levine S. S., Cole M. F., Frampton G. M., Brambrink T., Johnstone S., Guenther M. G., Johnston W. K., Wernig M., Newman J., Calabrese J. M., Dennis L. M., Volkert T. L., Gupta S., Love J., Hannett N., Sharp P. A., Bartel D. P., Jaenisch R., Young R. A. (2008) Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell 134, 521–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bourguignon L. Y., Wong G., Earle C., Chen L. (2012) Hyaluronan-CD44v3 interaction with Oct4-Sox2-Nanog promotes miR-302 expression leading to self-renewal, clonal formation, and cisplatin resistance in cancer stem cells from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 32800–32824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang Z., Wu W. S. (2013) Sodium butyrate promotes generation of human iPS cells through induction of the miR302/367 cluster. Stem Cells Dev., DOI: 10.1089/scd.2012.0650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beischlag T. V., Luis Morales J., Hollingshead B. D., Perdew G. H. (2008) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 18, 207–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nguyen L. P., Bradfield C. A. (2008) The search for endogenous activators of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 102–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lindsey S., Papoutsakis E. T. (2012) The evolving role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) in the normophysiology of hematopoiesis. Stem Cell Rev. 8, 1223–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miao W., Hu L., Scrivens P. J., Batist G. (2005) Transcriptional regulation of NF-E2 p45-related factor (NRF2) expression by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-xenobiotic response element signaling pathway: direct cross-talk between phase I and II drug-metabolizing enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20340–20348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reyes-Hernández O. D., Mejía-García A., Sánchez-Ocampo E. M., Cabañas-Cortés M. A., Ramírez P., Chávez-González L., Gonzalez F. J., Elizondo G. (2010) Ube2l3 gene expression is modulated by activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor: implications for p53 ubiquitination. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80, 932–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vogel C. F., Sciullo E., Matsumura F. (2007) Involvement of RelB in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated induction of chemokines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 363, 722–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boitano A. E., Wang J., Romeo R., Bouchez L. C., Parker A. E., Sutton S. E., Walker J. R., Flaveny C. A., Perdew G. H., Denison M. S., Schultz P. G., Cooke M. P. (2010) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonists promote the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Science 329, 1345–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kiss E. A., Vonarbourg C., Kopfmann S., Hobeika E., Finke D., Esser C., Diefenbach A. (2011) Natural aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands control organogenesis of intestinal lymphoid follicles. Science 334, 1561–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kimura A., Naka T., Nohara K., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Kishimoto T. (2008) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates Stat1 activation and participates in the development of Th17 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9721–9726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Veldhoen M., Hirota K., Westendorf A. M., Buer J., Dumoutier L., Renauld J. C., Stockinger B. (2008) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 453, 106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Akahoshi E., Yoshimura S., Ishihara-Sugano M. (2006) Over-expression of AhR (aryl hydrocarbon receptor) induces neural differentiation of Neuro2a cells: neurotoxicology study. Environ. Health 5, 1–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nukaya M., Walisser J. A., Moran S. M., Kennedy G. D., Bradfield C. A. (2010) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator in hepatocytes is required for aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated adaptive and toxic responses in liver. Toxicol. Sci. 118, 554–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zaher H., Fernandez-Salguero P. M., Letterio J., Sheikh M. S., Fornace A. J., Jr., Roberts A. B., Gonzalez F. J. (1998) The involvement of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the activation of transforming growth factor-β and apoptosis. Mol. Pharmacol. 54, 313–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chakrabarti R., Subramaniam V., Abdalla S., Jothy S., Prud'homme G. J. (2009) Tranilast inhibits the growth and metastasis of mammary carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs 20, 334–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rogosnitzky M., Danks R., Kardash E. (2012) Therapeutic potential of tranilast, an anti-allergy drug, in proliferative disorders. Anticancer Res 32, 2471–2478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Samavarchi-Tehrani P., Golipour A., David L., Sung H. K., Beyer T. A., Datti A., Woltjen K., Nagy A., Wrana J. L. (2010) Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 7, 64–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li R., Liang J., Ni S., Zhou T., Qing X., Li H., He W., Chen J., Li F., Zhuang Q., Qin B., Xu J., Li W., Yang J., Gan Y., Qin D., Feng S., Song H., Yang D., Zhang B., Zeng L., Lai L., Esteban M. A., Pei D. (2010) A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell 7, 51–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.