Abstract

PURPOSE

Parents of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) may face emotional distress while managing intense treatments with uncertain outcomes. We evaluated a brief parental emotional functioning (PREMO) screener from a health-related quality of life instrument to identify parental emotional distress, as measured by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID).

METHODS

As part of a longitudinal pediatric HSCT study, parents (N=165) completed the Child Health Ratings Inventories, which contain the 7-item PREMO screener. Some parents (n=117) also completed SCID modules for anxiety, mood, and adjustment disorders at baseline and/or 12 months. A composite outcome was created for threshold or subthreshold levels of any of these disorders. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis assessed how the PREMO screener predicted emotional distress as measured by the SCID. A prediction model was then built.

RESULTS

52% of parents completing the SCID had an Axis I disorder at baseline, while 41% had an Axis I disorder at 12 months. The area under the ROC curve was 0.75 for the PREMO screener and 0.81 for the prediction model.

CONCLUSIONS

The PREMO screener may identify parents with, or at risk for, emotional distress and facilitate further evaluation and intervention.

Keywords: quality of life, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, ROC analysis, pediatric

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) offers potentially life-saving treatment for children with disorders of the bone marrow, immune system, and metabolism. However, HSCT can be physically and psychologically taxing for the children and their parents. Research has shown that parents of children with cancer attribute psychological distress to uncertainty about their child’s health, loss of control, managing both their child’s and their own emotions, and putting their child’s needs first.[1–3] Consequently, parental depression has been linked with the child’s emotional distress preceding HSCT.[4,5]

Using a brief screener to identify parents at risk for emotional distress would help overcome impracticalities of having all parents complete a clinical evaluation or Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Generic health-related quality of life (HRQL) measures (e.g., 5-item Mental Health Index [6]) have been used as mental health screeners. [7,8] However, they have been validated only against other self-reported screening tests (e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire) not directly against clinical evaluations using structured diagnostic interviews performed by trained mental health professionals. [7,9]

The purpose of this study was to examine how the 7-item parent emotional functioning (PREMO) screener from the parent version of the Child Health Ratings Inventories (CHRIs) [10,11] performed at identifying emotional distress based on DSM-IV criteria for selected Axis I disorders. Using the SCID diagnoses as the “gold standard,” receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to estimate the screener’s predictive ability. A prediction model was then built.

METHODS

Participants

This study drew on 165 parents from a HRQL study that followed pediatric HSCT recipients (age 5–18) and their parents longitudinally over the first year of transplant. [5,12] Each child-parent dyad had only one parent participant who was selected based on their physical involvement in the child’s care. The PREMO screener was required of all parent participants at study entry and was the target of data collection activities at each study assessment period, whereas the SCID was an optional secondary measure at baseline (pre-HSCT) and/or 12 months. Parents of children who died or withdrew before 12 months did not complete subsequent study measures. Analyses were restricted to 117 parents who completed the SCID at baseline and/or 12 months (baseline only: n=41; 12 months only: n=9; both: n=67).

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID)

Parental emotional distress was a dichotomous variable based on the SCID Anxiety, Mood, and Adjustment Modules. Parents were considered to have a current (last 30 days) Axis I disorder if they met subthreshold/threshold criteria for at least one of these disorders. Threshold, per the DSM-IV criteria, indicates a constellation of symptoms and impairment of a specified duration of time, while subthreshold indicates either symptoms or impairment. Subthreshold was included because of its association with significant distress.[13,14] The SCID overview included a yes/no question about parents’ history of psychiatric medication use. Trained study mental health providers administered, audiotaped, and scored the SCID. The audiotape and score were reviewed by the study psychiatrist (GC) who performed a best estimate determination.

Child Health-Ratings Inventories (CHRIs).[10,11]

The parental version of the CHRIs includes two principal sections: (1) parent’s ratings of his/her child’s functioning; (2) parent’s rating of his/her own functioning. Three domains of generic HRQL are formed for each section: physical, role, and emotional functioning.[10] This study used the 7-item parental emotional functioning domain as the PREMO screener (Table 1), which takes less than 2 minutes to complete. Using the half-scale rule, the 7 items were averaged to create a summary score and transformed to a 100-point scale (100=higher functioning).

Table 1.

Content of the PREMO screener

| Question | Please select the one response that is most applicable |

|---|---|

| During the past week, how nervous, worried, or fidgety have you felt? | Not at all A little Some A lot A whole lot |

| During the past week, how happy or sad have you been? | Really happy Pretty happy Happy A little sad Sad |

During the past week, how often:a

|

All of the time Most of the time Some of the time A little of the time None of the time |

Abbreviations: PREMO=parent emotional functioning

These five questions were asked in a matrix form with a separate response elicited for each question.

Demographic and Medical Information

Parents reported demographic characteristics about themselves and their child. Research staff collected clinical data from medical records, including duration of illness, transplant type (autologous, related allogeneic, unrelated allogeneic), and causal diagnosis (malignancy vs. non-malignancy).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics and PREMO screener scores were described. To determine if there were differences in demographic and clinical characteristics by completion of the SCID, the two-sample t-test or chi-square test was used. For skewed data or small expected cell counts, the Wilcoxon rank sum or Fisher’s exact test was used.

Validation of the PREMO Screener

The performance of the PREMO screener for identifying parents with emotional distressed based on DSM-IV criteria for Axis I disorders was measured by calculating the area under the ROC curve and plotting the ROC curve and calibration plot. The area under the ROC curve measures discrimination while the ROC plot shows sensitivity vs. 1-specificity for all predicted probabilities. [15] The calibration plot shows how well the predictions agree with the observed rate for different quintiles of predicted probability.

We accounted for correlations over time among parents completing both the baseline and 12 month measures by using a generalized estimation equation model (GEE in R) with a binomial distribution, logit link function, and unstructured covariance. Results were used to plot and calculate the area under the ROC curve.[16] Standard error (SE) of the area under the ROC curve was calculated by bootstrapping 200 samples.

Prediction Model

Among parents completing the SCID, we compared demographic and clinical characteristics, PREMO screener scores, and history of psychiatric medication use by presence of an Axis I disorder. GEE was used to account for correlations over time. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. Any variable with p<0.10 was considered for inclusion in the prediction model. Using the area under the ROC curve, the magnitude of the estimate, and the p-value from the multivariate model, we selected the final prediction model. Its performance was assessed by calculating the area under the ROC curve and plotting the ROC curve and calibration plot.

Analyses were done using R (version 2.14.1) and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC); the alpha-level was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

After excluding two parents with missing data, the sample size was 115. There were statistically significant differences in parent education (p=0.03), race/ethnicity (p=0.03), and transplant center (p<0.0001) by SCID completion (Table 2). More than half of parents (52.0%, n=53) met subthreshold/threshold criteria for an Axis I disorders at baseline (12.7% anxiety only, 11.8% mood only, 15.7% adjustment only, 11.8% multiple), while 41.1% (n=30) met criteria at 12 months (6.8% anxiety only, 11.0% mood only, 17.8% adjustment only, 5.5% multiple). Regarding the severity of those with Axis I disorders, approximately two-thirds of parent met threshold criteria, while one-third met subthreshold criteria. Among parents completing the SCID at baseline and 12 months (n=64), 29.5% met subthreshold/threshold criteria for Axis I disorders at both times, 18.8% met criteria at baseline only, and 6.3% met criteria at 12 months only.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of parents and children by parental completion of SCID at baseline and/or 12 months

| Parent did not complete SCID, n=48 | Parent completed SCID, n=117 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Parent Demographics

| |||

| Parent age in years, mean (SD) | 38.8 (7.5) | 38.9 (6.6) | 0.96 |

| Female parent, n (%) | 39 (81.3%) | 100 (85.5%) | 0.50 |

| Parent education, n (%) | |||

| <HS graduate | 8 (16.7%) | 5 (4.3%) | 0.03 |

| HS graduate | 15 (31.3%) | 30 (25.6%) | |

| Some College | 12 (25.0%) | 35 (29.9%) | |

| College or more | 13 (27.1%) | 47 (40.2%) | |

| Household income, n (%) | |||

| <$40K | 21 (45.7%) | 33 (29.0%) | 0.24 |

| $40K–$59K | 9 (19.6%) | 27 (23.7%) | |

| $60–$79K | 5 (10.9%) | 15 (13.2%) | |

| >$80K | 11 (23.9%) | 39 (34.2%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 25 (54.4%) | 89 (76.1%) | 0.03a |

| Non-Hispanic non-white | 6 (13.0%) | 8 (6.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 15 (32.6%) | 19 (16.2%) | |

| Refused, Unknown | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | |

|

| |||

|

Child Demographics

| |||

| Child age in years, mean (SD) | 10.3 (3.5) | 11.0 (4.0) | 0.29 |

| Female Child, n (%) | 23 (47.9%) | 59 (50.4%) | 0.77 |

|

| |||

|

Child Clinical Characteristics

| |||

| Duration of illness in months, median (25th–75th percentiles) | 16.5 (5.0–42.0) | 7.0 (5.0–30.0) | 0.14 |

| Transplant Center, n (%) | |||

| Dana Farber Cancer Institute | 7 (14.6%) | 58 (49.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Milwaukee | 9 (18.8%) | 12 (10.3%) | |

| Texas | 23 (47.9%) | 6 (5.1%) | |

| City of Hope | 5 (10.4%) | 23 (19.7%) | |

| Pittsburgh | 2 (4.2%) | 2 (1.7%) | |

| Seattle | 2 (4.2%) | 16 (13.7%) | |

|

| |||

|

Parent Emotional Status

| |||

| PREMO screener score, mean (SD) | 53.3 (20.2) | 47.5 (17.4) | 0.07 |

Abbreviations: PREMO=parent emotional functioning

p-value based on Fisher’s Exact Test due to low expected cell counts

p-value based on Wilcoxon Rank Sum because of skewed distribution

Validation of PREMO Screener

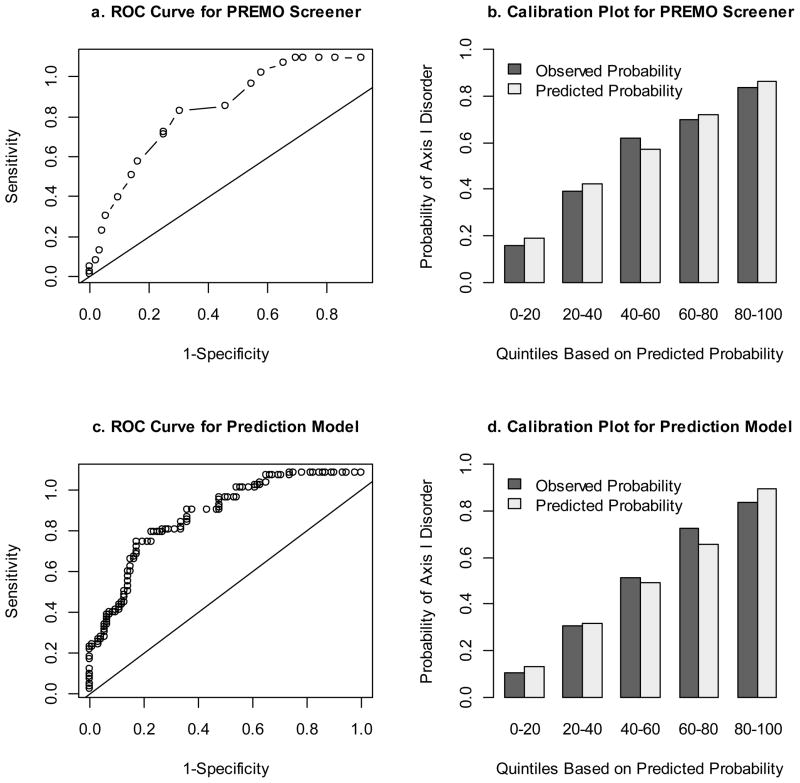

A half standard deviation increase on the PRREMO screener (SD=18 points) was associated with nearly a 40% decrease in odds of an Axis I disorder (OR=0.62, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.73, p<0.0001). The area under the ROC curve (Figure 1a) was 0.75 (SE=0.04), demonstrating acceptable discrimination. [17] The screener was also well calibrated (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

ROC curves and calibration plots for predicting Axis I disorders using the PREMO screener or the prediction model.

Abbreviations: ROC=receiver operating characteristic; PREMO=parent emotional functioning

Prediction Model

In addition to the PREMO screener, child age (p=0.07), child gender (p=0.10), transplant type (p=0.45 for related, p=0.07 for unrelated, comparator= autologous), and history of psychiatric medication use (p=0.0002) were significant at the 0.10-level (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis for presence of Axis I disorder at baseline and/or 12 months, n=115

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

|

Parent Demographics

| ||

| Parent age in years | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 0.48 |

| Female parent | 1.3 (0.5, 3.3) | 0.57 |

| Parent education | ||

| High school or less | 1.8 (0.8, 3.9) | 0.16 |

| Some college | 0.7 (0.3, 1.5) | 0.33 |

| College or more | Reference | |

| Parent income | ||

| <$40K | 1.2 (0.5, 2.9) | 0.65 |

| $40K–$59K | 1.1 (0.4, 2.7) | 0.83 |

| $60–$79K | 0.7 (0.2, 2.1) | 0.51 |

| >$80K | Reference | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | Reference | |

| Non-Hispanic non-white | 0.9 (0.2, 4.0) | 0.93 |

| Hispanic | 0.6 (0.2, 1.6) | 0.29 |

|

| ||

|

Child Demographics

| ||

| Child age in years | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 0.07 |

| Female child | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.10 |

|

| ||

|

Child Clinical Characteristics

| ||

| Log duration of illness in months | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.21 |

| Transplant type | ||

| Autologous | Reference | |

| Allogeneic, related | 0.7 (0.3, 1.7) | 0.45 |

| Allogeneic, unrelated | 0.5 (0.2, 1.1) | 0.07 |

| Causal Malignancy | 1.2 (0.5, 3.0) | 0.72 |

| Parent Emotional Status | ||

| PREMO screener score (for ½ SD change) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Lifetime use of psychiatric Rx | 3.5 (1.8, 6.7) | 0.0002 |

Abbreviations: SCID= Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; Rx=prescription; PREMO=parent emotional functioning

The prediction model included all univariate significant variables. Based on model p-values, transplant type was collapsed into autologous and allogeneic (related or unrelated). Having a female child (OR=0.4, 95% CI: 0.2, 1.0, p=0.05, comparator=male) or having a higher PREMO screener score (OR=0.6 for half a standard deviation (SD=18), 95% CI: 0.5, 0.7, p<0.0001) was associated with lower odds of an Axis I disorder. On the other hand, having an older child (OR=1.1, 95% CI: 1.0, 1.2, p=0.04), a child with an autologous transplant (OR=2.9, 95% CI: 0.5, 0.7, p=0.03, comparator=allogeneic), or a history of psychiatric medication use (OR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.2, 5.3, p=0.02) was associated with higher odds of an Axis I disorder. The area under the ROC curve (Figure 1c) was 0.81 (SE=0.03), demonstrating excellent discrimination. [17] The prediction model was also well calibrated (Figure 1d). [Table 4]

Table 4. Prediction model for.

presence of Axis I disorder at baseline and/or 12 months, n=115

| OR(95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Intercept | 4.8 (0.8, 28.1) | 0.08 |

|

| ||

|

Child Demographics

| ||

| Child age in years | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 0.04 |

| Female child | 0.4 (0.2, 1.0) | 0.05 |

|

| ||

|

Child Clinical Characteristics

| ||

| Autologous Transplant | 2.9 (1.1, 7.3) | 0.03 |

|

| ||

|

Parent Emotional Status

| ||

| PREMO screener score (for ½ SD change) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Lifetime use of psychiatric Rx | 2.5 (1.2, 5.3) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: Rx=prescription; PREMO=parent emotional functioning

DISCUSSION

Results indicate that 50% of parents of children undergoing HSCT experience emotional distress at baseline and 40% at 12 months. Using ROC analysis, we found that the 7-item PREMO screener successfully identified parents with emotional distress based on DSM-IV criteria for Axis I disorders. Unlike previous validation studies using self-reported generic HRQL measures as screeners for emotional distress, we used the SCID as the gold standard. [7,9]

A prediction model that also included child age, child gender, transplant type, and history of psychiatric medication use improved model discrimination. These variables were all available at the time of transplant, making them potentially useful in a clinical setting. Additionally, the item asking about history of psychiatric medication use identifies parents with previous mental health issues who may be at higher risk of reoccurrence.[18,19]

Our results reveal that many parents of children undergoing HSCT meet subthreshold/threshold criteria for an Axis I disorders, mirroring the results of other studies about heightened parental emotional distress.[20,21] Thus, there is a clinical need to identify these parents and provide appropriate care and support, especially given their pivotal caregiving role. A brief and effective way to identify parental emotional distress and make recommendations for treatment has the potential to improve emotional outcomes for these parents, which could then improve clinical outcomes for the recovering child. Future research is needed to determine a PREMO screener cut-off based on sensitivity and specificity values that would “rule in” parents at risk for emotional distress (sensitivity) while not “ruling out” (specificity) too many at-risk parents. As an illustrative example, we selected sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 43%, which corresponds to a score of 62.5 on the PREMO screener.

We acknowledge the study’s limitations. First, the sample size was too small to split the dataset into a training dataset and a validation dataset. Second, not all parents elected to complete the SCID and there were differences in completion by education, race/ethnicity, and baseline PREMO screener score.

Despite these limitations, we have evaluated the performance of the PREMO screener and prediction model for identifying parents with, or at risk for, clinically significant emotional distress and facilitating further evaluation and intervention. Given that half of these parents met subthreshold/threshold criteria for an Axis I disorder, this population is in need of an effective, but efficient screening method.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by American Cancer Society, Research Scholars Grant PB02-186-01-PBP (SKP) and the National Cancer Institute, R01 CA 119196 (SKP).

We would like to thank Sara Ratichek, MA, for her comments on earlier drafts.

Abbreviations

- CHRIs

Child Health Ratings Inventories

- HRQL

health-related quality of life

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant

- PREMO

parent emotional functioning

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SCID

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

Footnotes

This project was presented in part at the October 2010 International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) in Boston, MA, USA.

Reference List

- 1.Boman KK, Viksten J, Kogner P, Samuelsson U. Serious illness in childhood: the different threats of cancer and diabetes from a parent perspective. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young B, Dixon-Woods M, Findlay M, Heney D. Parenting in a crisis: conceptualising mothers of children with cancer. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:1835–1847. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrath P. Beginning treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: insights from the parents' perspective. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2002;29:988–996. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.988-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jobe-Shields L, Alderfer M, Barrera M, Vannatta K, Currier J, Phipps S. Parental Depression and Family Environment Predict Distress in Children Prior to Stem-Cell Transplantation. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30:140–146. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181976a59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons S, Terrin N, Ratichek S, Tighiouart H, Recklitis CJ, Chang G. Trajectories of HRQL following Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) Quality of Life Research. 2009:A-44. Abstract # 1420. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tavella R, Air T, Tucker G, Adams R, Beltrame JF, Schrader G. Using the Short Form-36 mental summary score as an indicator of depressive symptoms in patients with coronary heart disease. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:1105–1113. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9671-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuijpers P, Smits N, Donker T, ten HM, de GR. Screening for mood and anxiety disorders with the five-item, the three-item, and the two-item Mental Health Inventory. Psychiatry Research. 2009;168:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbons LE, Feldman BJ, Crane HM, Mugavero M, Willig JH, Patrick D, Schumacher J, Saag M, Kitahata MM, Crane PK. Migrating from a legacy fixed-format measure to CAT administration: calibrating the PHQ-9 to the PROMIS depression measures. Quality of Life Research. 2011;20:1349–1357. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9882-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsons SK, Shih MC, Mayer DK, Barlow SE, Supran SE, Levy SL, Greenfield S, Kaplan SH. Preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Child Health Ratings Inventories (CHRIs) and Disease-Specific Impairment Inventory-HSCT (DSII-HSCT) in parents and children. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14:1613–1625. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-1004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons SK, Shih MC, DuHamel KN, Ostroff J, Mayer DK, Austin J, Martini DR, Williams SE, Mee L, Sexson S, Kaplan SH, Redd WH, Manne S. Maternal perspectives on children's health-related quality of life during the first year after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:1100–1115. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang G, Ratichek SJ, Recklitis C, Syrjala K, Patel SK, Harris L, Rodday AM, Tighiouart H, Parsons SK. Children's psychological distress during pediatric HSCT: Parent and child perspectives. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2012;58:289–296. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olfson M, Broadhead WE, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Farber L, Hoven C, Kathol R. Subthreshold psychiatric symptoms in a primary care group practice. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:880–886. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall RD, Olfson M, Hellman F, Blanco C, Guardino M, Struening EL. Comorbidity, impairment, and suicidality in subthreshold PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1467–1473. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrel F. Regression modeling strategies: with application to linear models, logistic regression and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obuchowski NA. Nonparametric analysis of clustered ROC curve data. Biometrics. 1997;53:567–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. Assessing the fit of the model; pp. 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards D. Prevalence and clinical course of depression: a review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:1117–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW, Eisen JL, Weisberg RB, Pagano M, Shea MT, Keller MB. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: a 12-year prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1179–1187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrera M, D'Agostino NM, Gibson J, Gilbert T, Weksberg R, Malkin D. Predictors and mediators of psychological adjustment in mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:630–641. doi: 10.1002/pon.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manne S, Nereo N, DuHamel K, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini R, Williams S, Mee L, Sexson S, Lewis J, Vickberg SJ, Redd WH. Anxiety and depression in mothers of children undergoing bone marrow transplant: symptom prevalence and use of the Beck depression and Beck anxiety inventories as screening instruments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1037–1047. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]