Abstract

For six clinical isolates of Chlamydia trachomatis, in vitro susceptibility to erythromycin, azithromycin, and josamycin has been determined. Four isolates were resistant to all the antibiotics and had the mutations A2058C and T2611C (Escherichia coli numbering) in the 23S rRNA gene. All the isolates had mixed populations of bacteria that did and did not carry 23S rRNA gene mutations.

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular parasite that causes a wide range of inflammations of the urogenital tract. Clinical isolates showing resistance to azithromycin and associated with a recurrent infection have been described previously (19). The resistance of various microorganisms to macrolides is often associated with mutations in ribosomal protein genes, particularly in L4 and L22, as well as with mutations in the peptidyl transferase region of the 23S rRNA gene (2, 3, 6, 13, 21). The objective of the present work was that of finding macrolide-resistant C. trachomatis clinical isolates and studying them for possible mutations in 23S rRNA, L22, and L4 genes.

C. trachomatis isolates were obtained from four patients attending the D.O. Ott Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Saint Petersburg, Russia) during 2000 to 2002. The reference C. trachomatis strain was kindly provided by Eva Hjelm (Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden).

McCoy cells were seeded into 24-well cell culture plates (approximately 2 × 105 cells per well) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h to achieve monolayer confluence. For C. trachomatis growth in cultures, Eagle's medium containing 0.5% glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, 25 μg of vancomycin/ml, 25 μg of gentamicin/ml, and 2.5 μg of amphotericin B/ml was used. The cell monolayer was infected with an inoculum which produced 20 to 30 inclusions per field under a magnification of ×400. The infected cells were centrifuged at 1,700 × g for an hour and incubated for 2 h at 37°C; after that, the medium was removed and the cells were washed with 0.5 ml of Eagle medium. The infected cells were then overlaid with the growth medium containing serial twofold dilutions of the antibiotic (concentration range, 0.01 to 5.12 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 72 h. The following antibacterial agents were used: erythromycin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and josamycin and azithromycin (Pfizer/MACK, Illertissen, Germany). The inclusions were detected by direct immunofluorescence using fluorescein-labeled antibodies against major outer-membrane protein (MOMP) (Chlamyset Antigen FA, Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland). The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which no typical inclusions were observed. To assay minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBC), the cells were washed from the antibiotic 72 h after infection and the fresh cell monolayer was reinfected. The MBC was defined as that resulting in an absence of inclusions in the monolayer after a 72-hour incubation.

The isolation of a mixture of C. trachomatis and McCoy cell genomic DNA and DNA from uninfected McCoy cells was performed by using a standard method of phenol-chloroform extraction. The RNA was isolated using the SV total RNA isolation system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The nucleotide sequences of the primers used are shown in Table 1. The primers flanking a variable region of the MOMP were used to determine the serotype of each isolate. Sequencing was done using both DNA strands by means of an fmol DNA cycle sequencing system (Promega).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for the amplification of fragments of ribosomal protein, MOMP, and 23S rRNA genes

| Primer target | Primer and sequence | Position |

|---|---|---|

| L4 protein | l4-f, 5′ gaagtttgaattgcctgatgc 3′ | 45-65a |

| l4-r, 5′ ggcttaggaccgaaaacaatc 3′ | 278-258a | |

| L22 protein | l22-f, 5′ agctgcaggattgatgagaaa 3′ | 54-74a |

| l22-r, 5′ gttagatgactcgtgcgcttc 3′ | 308-288a | |

| 23S rRNA | rr-f, 5′ aagttccgacctgcacgaatgg 3′ | 1952-1973b |

| rr-r, 5′ tccattccggtcctctcgtac 3′ | 2675-2656b | |

| rrg-f, 5′ aattccttgtcgggtaagttc 3′ | 1937-1957b | |

| al1-r, 5′ cgttatgatcccaggatccct 3′ | 5927-5907c | |

| al2-r, 5′ cccaatatagaaccgaaaattcga 3′ | 5451-5428d | |

| MOMP | Se-f, 5′ ccaatatgctcaatctaacc 3′ | 1932-1951a |

| Se-r, 5′ aattgcaaggagacgatttg 3′ | 2656-2647a |

Isolates 1, 2, 4-1, and 4-2 demonstrated resistance to all the macrolides (Table 2). The MIC and MBC of each of the drugs were above 5.12 μg/ml for these isolates (compared to between 0.02 and 0.16 μg/ml for the reference strain). Isolates 3-1 and 3-2 were sensitive to all the drugs. The observed resistance was heterotypic; i.e., the inclusions observed were small and their number in the presence of antibiotics was much lower. Resistant isolates could be visually distinguished from sensitive ones, which showed no inclusions at the drug concentrations defined as the MIC and MBC.

TABLE 2.

Results of the assay for antibiotic resistance of C. trachomatis clinical isolates and mutations in 23S rRNA and L22 genes

| Patient and description | Isolate and date obtained | Antibiotic susceptibility (μg/ml)

|

Sero- type | Mutation

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythromycin

|

Azithromycin

|

Josamycin

|

23S rRNAa | L22b | ||||||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |||||

| 1, chronic salpingitis | 1, 4/10/2000 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | G | + | − |

| 2, endocervicitis (the first episode of infection was observed in 1997; spiramycin was used for treatment) | 2, 1/5/2000 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | D | + | + |

| 3, vaginal discharge (treated with josamycin [500 mg] twice daily from 12/12/2001 to 12/21/2001) | 3-1 (before treatment), 1/5/2000 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | B | − | + |

| 3-2 (after treatment), 10/20/2001 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | B | − | + | |

| 4, urethritis (treated with josamycin [500 mg] twice daily from 6/26/2002 to 7/5/2002) | 4-1 (before treatment), 6/17/2002 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | I | + | + |

| 4-2 (after treatment), 10/2/2002 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | >5.12 | I | + | + | |

| C. trachomatis reference strain D/UW-3/Cx (ATCC VR-885) | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.08 | D | − | − | |

Double mutations: A2058C and T2611C (E. coli numbering).

Triple mutations: Gly52(GGC)→Ser(AGC), Arg65(CGT)→Cys(TGT), and Val77(GTC)→Ala(GCC) (bases relative to ATG).

Table 2 shows all the mutations found as a result of sequencing the genes that are coding targets for macrolides. The studied region of gene L4 in all of the isolates showed no difference from that of the published GenBank sequence (NC000117.1). In the L22 gene of all isolates except isolate 1, a triple mutation was found: Gly52(GGC)→Ser(AGC), Arg65(CGT)→Cys(TGT), and Val77(GTC)→Ala(GCC).

Amplification of the peptidyl transferase loop of the 23S rRNA gene was performed with the rr primers. The sequencing of isolates 1, 2, 4-1, and 4-2 with both the forward and reverse primers revealed that at certain positions (the same positions for all isolates), a mixture of termination products was present. At positions 2058 and 2611 (Escherichia coli numbering)—positions at which mutations are significant for developing drug resistance to macrolides)—both wild-type (A2058 and T2611) and mutant (C2058 and C2611) bases were found. Since the C. trachomatis genome contains two copies of the 23S rRNA gene (4), the result described above could mean either the occurrence of mutations in only one copy of the gene in all bacteria or the occurrence of two bacterial populations that were different at those loci.

To determine whether the mutations were homo- or heterozygous, a two-stage amplification of the DNA obtained from isolate 1 was carried out. The first amplification was run with a pair of primers of which the reverse primer was unique for the 3′ region of each operon (al1 and al2) whereas the forward primer was common to both operons (rrg). At the second stage, the product was amplified with the pair of rr primers. The amplicons were then cloned into pGEM-T-Easy vector (Promega). Sequencing of the cloned inserts from six randomly selected plasmids showed that both the wild-type and mutant genes of 23S rRNA had been amplified with each of the reverse primers. Sequencing of the cDNA synthesized from isolated RNAs showed that both variants of the 23S rRNA were produced.

We supposed that we would be able to isolate a resistant population of chlamydiae in the presence of azithromycin if the mutations in the 23S rRNA gene were associated with resistance to macrolides.

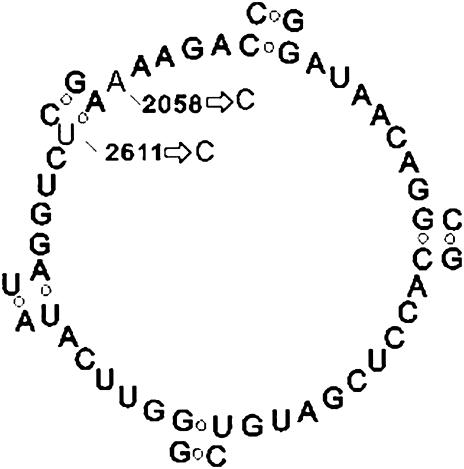

We carried out one passage with isolate 1 on cell culture in the presence of 5.12 μg of azithromycin/ml, isolated the DNA, and sequenced it between the two rr primers. At all positions where we had seen a mixture of termination products we now saw only one, corresponding to the mutant version. This fact indicated that mutations in both copies of the 23S rRNA were required for the bacteria to survive in the presence of the drug. Since the peptidyl transferase loops are similar in different microorganisms (21), regions that form the loop in C. trachomatis can be identified (Fig. 1). Figure 1 shows mutations A2058C and T2611C. Mutation T2611C destroys the hydrogen bond that exists between bases A2057 and T2611. After the single passage in the presence of azithromycin, we performed seven passages of the culture without the drug. After each passage the number of inclusions in the infected monolayer decreased until the isolate died. A similar experiment was also performed with isolate 2, and results were the same.

FIG. 1.

The secondary structure of the central portion of domain V (the peptidyl transferase loop) of the 23S rRNA gene of a C. trachomatis clinical isolate resistant to azithromycin (as determined on the basis of the model by Egebjerg et al.) (2). The arrows show mutations A2058C to T2611C (E. coli numbering).

We therefore concluded that a clinical C. trachomatis isolate can contain organisms differing in their levels of susceptibility to antibiotics, some of them resistant to macrolides and carrying mutations in the 23S rRNA gene and others sensitive to macrolides and lacking these mutations. It seems that the viability of bacteria carrying the mutations in both alleles of the 23S rRNA gene is low. The phenomenon of reduced viability of bacteria resulting from acquisition of mutations that lead to drug resistance is well known.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that mutations in the peptidyl transferase region of the 23S rRNA gene have been found in macrolide-resistant C. trachomatis. A considerable body of evidence for the interaction of the ribosome with macrolides has been accumulated to date, and it has been demonstrated that the peptidyl transferase region of domain V of the 23S rRNA plays an important role (1, 7, 8, 9, 12, 16, 17, 21). Macrolide-resistant strains of E. coli have been isolated that possess a multicopy plasmid expressing a mutant allele of gene rr at position 2058 (18). Subsequently, mutations in this gene have been found in clinical isolates of pathogenic bacteria. In various bacteria the mutation at A2058 is most often associated with a higher level of resistance to all macrolides as well as to lincosamide and streptogramin B, substances that are chemically distinct from macrolides but have a similar mechanism of action in bacterial protein synthesis (11, 15, 18; for a review, see reference 22). Mutations at positions 2057 and 2611 result in disturbance of the hydrogen bond between them and are associated with resistance to erythromycin in propionibacteria (14), Streptococcus pneumoniae (20), E. coli (5), and S. pyogenes (10).

Along with mutations in domain V or II of the 23S rRNA gene, mutations in ribosomal proteins L4 and L22 may also be associated with resistance to various macrolides (2, 13, 20). We have found a triple mutation, Gly52(GGC)→Ser(AGC), Arg65(CGT)→Cys(TGT), and Val77(GTC)→Ala(GCC), in the L22 protein in five out of six studied clinical isolates but have not yet assessed its role in C. trachomatis resistance. The mutations reside in a nonconserved region of the L22 protein. Such mutations have not been found in other macrolide-resistant bacteria. Because we have also found these mutations in isolates that were sensitive to macrolides in vitro (3-1 and 3-2), we believe that they are not responsible for macrolide resistance.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that the relationship between the antibiotic resistance manifested by C. trachomatis in vitro and the efficiency of antichlamydial therapy has yet to be established. There have been no studies of a representative quantity of C. trachomatis clinical isolates characterized by their drug resistance characteristics and compared with respect to the results of patient treatment. The findings for mutations in the 23S rRNA gene associated with C. trachomatis resistance to macrolides and described here will facilitate such a study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berisio, R., J. Harms, F. Schluenzen, R. Zarivach, P. Fucini, and A. Yonath. 2003. Structural insight into the antibiotic action of telithromycin against resistant mutants. J. Bacteriol. 185:4276-4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canu, A., B. Malbruny, M. Coquemont, T. A. Davies, P. C. Appelbaum, and R. Leclercq. 2002. Diversity of ribosomal mutations conferring resistance to macrolides, clindamycin, streptogramin, and telithromycin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:125-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egebjerg, J., N. Larsen, and R. A. Garrett. 1990. Structural map of 23S rRNA, p. 168-179. In W. E. Hill, A. Dalberg, R. A. Garrett, P. B. Moore, D. Schlessinger, and J. R. Warner (ed.), The ribosome: structure, function, and evolution. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 4.Engel, J. N., and D. Ganem. 1987. Chlamydial rRNA operons: gene organization and identification of putative tandem promoters. J. Bacteriol. 169:5678-5685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ettayebi, M., S. M. Prasad, and E. A. Morgan. 1985. Chloramphenicol-erythromycin resistance mutations in a 23S rRNA gene of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 162:551-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregory, S. T., J. H. Cate, and A. E. Dahlberg. 2001. Spontaneous erythromycin resistance mutation in a 23S rRNA gene, rrlA, of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus IB-21. J. Bacteriol. 183:4382-4385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen, J. L., J. A. Ippoplito, N. Ban, P. Nissen, P. B. Moore, and T. A. Steits. 2002. The structures of four macrolide antibiotics bound to the large ribosomal subunit. Mol. Cell 10:117-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen, L. H., P. Mauvais, and S. Douthwaite. 1999. The macrolide-ketolide antibiotic binding site is formed by structures in domains II and V of 23S ribosomal RNA. Mol. Microbiol. 31:623-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucier, T. S., K. Heitzman, S. K. Liu, and P. C. Hu. 1995. Transition mutations in the 23S rRNA of erythromycin-resistant isolates of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2770-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malbruny, B., K. Nagai, M. Coquemont, B. Bozdogan, A. T. Andrasevic, H. Hupkova, R. Leclercq, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2002. Resistance to macrolides in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes due to ribosomal mutations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:935-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier, A., L. Heifets, R. J. Wallace, Jr., Y. Zhang, B. A. Brown, P. Sander, and E. C. Bottger. 1996. Molecular mechanisms of clarithromycin resistance in Mycobacterium avium: observation of multiple 23S rDNA mutations in a clonal population. J. Infect. Dis. 174:354-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moazed, D., and H. F. Noller. 1987. Chloramphenicol, erythromycin, carbomycin and vernamycin B protect overlapping sites in the peptidyl transferase region of 23S ribosomal RNA. Biochimie 69:879-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pihlajamaki, M., J. Kataja, H. Seppala, J. Elliot, M. Leinonen, P. Huovinen, and J. Jalava. 2002. Ribosomal mutations in Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:654-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross, J. I., E. A. Eady, J. H. Cove, C. E. Jones, A. H. Ratyal, Y. W. Miller, S. Vyakrnam, and W. J. Cunliffe. 1997. Clinical resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin in cutaneous propionibacteria isolated from acne patients is associated with mutations in 23S rRNA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1162-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarpellini, P., P. Carrera, A. Cavallero, M. Cernuschi, G. Mezzi, P. A. Testoni, A. Zingale, and A. Lazzarin. 2002. Direct detection of Helicobacter pylori mutations associated with macrolide resistance in gastric biopsy material taken from human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2234-2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlunzen, F., J. M. Harms, F. Franceschi, H. A. Hansen, H. Bartels, R. Zarivach, and A. Yonath. 2003. Structural basis for the antibiotic activity of ketolides and azalides. Structure (Cambridge) 11:329-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlunzen, F., R. Zarivach, J. Harms, A. Bashan, A. Tocilj, R. Albrecht, A. Yonath, and F. Franceschi. 2001. Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria. Nature 413:814-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sigmund, C. D., M. Ettayebi, and E. A. Morgan. 1984. Antibiotic resistance mutations in 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:4653-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somani, J., V. B. Bhullar, K. A. Workowski, C. E. Farshy, and C. M. Black. 2000. Multiple drug-resistant Chlamydia trachomatis associated with clinical treatment failure. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1421-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tait-Kamradt, A., T. Davies, M. Cronan, M. R. Jacobs, P. C. Applaud, and J. Sutcliffe. 2000. Mutations in 23S rRNA and ribosomal protein L4 account for resistance in pneumococcal strains selected in vitro by macrolide passage. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2118-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vester, B., and S. Douthwaite. 2001. Macrolide resistance conferred by base substitutions in 23S rRNA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisblum, B. 1995. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:577-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]