Abstract

Twenty-six Escherichia coli isolates recovered from food animal feces and retail ground meats and 14 urinary E. coli isolates from outpatients were shown to carry blaCMY-2. Similar CMY-2-encoding plasmids were found among seven human and three ground-pork isolates. These data indicate the community spread of blaCMY-2 in southern Taiwan.

The prevalence of plasmid-encoded AmpC-type β-lactamases that confer resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins on gram-negative bacilli in health care settings is becoming a global problem (15). The spread of blaCMY-2, a plasmid-mediated ampC-like gene (3), among Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals has recently been reported in North America and has raised a public health concern (1, 6, 21, 22, 26). Moreover, a connection between CMY-2-producing E. coli and Salmonella isolates from humans and those from food animals has been established in the United States (7, 22, 23, 26). blaCMY-2-carrying Salmonella and E. coli isolates associated with community-acquired infections were recently detected in Taiwan; thus, the community spread of blaCMY-2 in Taiwan was also suggested (24). The present study was conducted to confirm the speculation and to investigate the link between CMY-2-producing animal and human E. coli isolates in Taiwan.

A total of 212 ground meat and animal stool (GMAS) samples were screened for CMY-2-producing E. coli (Table 1). The samples of ground meat were purchased between June and July 2002 from six stores at three conventional open markets in Tainan City, in southern Taiwan. The animal stool samples were collected between September and October 2002 from two farms located in two counties adjacent to Tainan City. All meat stores, markets, and farms from which the GMAS samples were collected were randomly chosen. Ground meat was swabbed on the surface with sterilized cotton in saline, and animal stool samples were swabbed by immersing the tips of cotton swabs in the specimens. All swabs were inoculated onto eosin-methylene blue agar plates supplemented with 2 μg of ceftazidime, 2 μg of cefotaxime, or 64 μg of cefoxitin per ml. Plates were examined after incubation overnight at 35°C. Bacteria suspected to be E. coli on agar plates were identified by using the API 20E system (bioMérieux Vitek, Hazelwood, Mo.). Overall, 34 of the 212 samples yielded E. coli on 48 agar plates (Table 1). One isolate from each of the 48 plates was selected for study. None of the 48 isolates were found to produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases by the confirmatory disk diffusion tests recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (11, 12).

TABLE 1.

Summary of results of screening tests and PCR experiments for the detection of blaCMY-2-containing E. coli isolates in ground meats and food animal feces

| Source (no. of samples) | No. of samples yielding E. coli/no. of samples yielding blaCMY-2-positive isolates on agar platesa containing:

|

Total no. of agar plates grown with E. coli/total no. of blaCMY-2-positive isolates identified | Total no. of samples yielding E. coli on agar plates/total no. of samples with blaCMY-2-positive isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOX | CTX | CAZ | |||

| Ground chicken (100) | 6/2 | 8/5 | 9/7 | 23/14 | 15/14 |

| Market A (60) | 6/2 | 7/4 | 7/5 | 20/11 | 12/11 |

| Market B (20) | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| Market C (20) | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| Ground pork (50) | 1/0 | 0/0 | 8/1 | 9/1 | 8/1 |

| Market A (30) | 1/0 | 0/0 | 7/0 | 8/0 | 7/0 |

| Market B (10) | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| Market C (10) | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| Chicken stool (32)b | 1/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 2/1 | 2/1 |

| Porcine stool (30)c | 1/1 | 5/4 | 8/5 | 14/10 | 9/7 |

| All sources (212) | 9/3 | 13/9 | 26/14 | 48/26 | 34/23 |

Eosin-methylene blue agar plates supplemented with 64 μg of cefoxitin (FOX) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), 2 μg of cefotaxime (CTX) (Hoechst-Roussel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Somerville, N.J.), or 2 μg of ceftazidime (CAZ) (Glaxo Group Research Ltd., Greenford, United Kingdom) per ml.

These samples were collected from a poultry farm in Tainan County.

These samples were collected from a pig farm in Kaohsiung County.

PCR with primers ampC1 (5′-ATGATGAAAAAATCGTTATGC-3′) and ampC2 (5′-TTGCAGCTTTTCAAGAATGCGC-3′) was performed as described previously to amplify the entire blaCMY-2 gene (22, 23). PCR assays followed by nucleotide sequencing revealed that 26 of the 48 GMAS isolates possessed blaCMY-2 sequences (Table 1). Colony hybridization with a [α-32P]dCTP-labeled blaCMY-2 probe was performed as described previously (8, 24) and gave results consistent with those of the PCR assays. All 22 blaCMY-2-negative isolates were found to be susceptible to cefoxitin, ceftazidime, and cefotaxime by the standard disk diffusion tests (11, 12). Isoelectric focusing was performed with crude β-lactamase extracts prepared by sonication as described previously (4, 10, 25). All 26 blaCMY-2-positive isolates expressed two β-lactamases with pIs of 9.0 and 5.4, which comigrated alongside CMY-2 and TEM-1 (3, 5), respectively. These findings together confirm the community spread of CMY-2-producing E. coli in southern Taiwan. The 26 CMY-2 producers were recovered from 23 GMAS samples; one isolate from each sample was analyzed further.

Forty-two urinary E. coli isolates recovered from different outpatients in 2001 at the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, a 900-bed hospital in Tainan City, were resistant to cefoxitin based on the NCCLS criteria for the disk diffusion method and were also selected for study. blaCMY-2 was detected in 14 of the 42 isolates by PCR, nucleotide sequencing, and colony hybridization. Twelve of these isolates expressed two β-lactamases with pIs of 9.0 and 5.4, and two isolates expressed only a pI 9.0 β-lactamase.

Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis with the primer ERIC2 (5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG-3′) was performed as previously described (9, 20) with the 14 human and 23 nonreplicate GMAS CMY-2-producing isolates. Isolates exhibiting similar fingerprints (fewer than two band differences) on visual inspection were further analyzed by ribotyping with endonucleases EcoRI and HindIII (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) as described previously (14, 16). Genetic relatedness among studied isolates was interpreted according to the method of Tenover et al. (19), which was initially developed for the analysis of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles but can also be applied to ribotyping analysis (2). The results of RAPD analysis and ribotyping are summarized in Table 2. All human isolates differed from the GMAS isolates with regard to RAPD profiles or ribotypes generated with EcoRI or HindIII.

TABLE 2.

RAPD profiles, ribotypes, and non-β-lactam antibiotic resistance phenotypes of CMY-2-producing E. coli isolates and restricted patterns of transferred CMY-2-encoding plasmids

| Source and isolate | RAPD profilea | Ribotype withb:

|

Non-β-lactam antibiotic resistancec | EcoRI-restricted pattern of transferred plasmid (no. of transconjugants) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EcoRI | HindIII | ||||

| Human | |||||

| H1 and H2 | A | SXT, CHL | TP3 (2) | ||

| H3 | B | GEN, SXT | TP7 (1) | ||

| H4 | C | E3d | H3d | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP3 (1) |

| H5 | D | —e | Nod | ||

| H6 | G | E2c | H2c | GEN, SXT, CHL | TP6 (1) |

| H7 | G | E2e | H2d | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP3 (1) |

| H8 | G | E2f | H2d | GEN, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP3 (1) |

| H9 | J | GEN, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP6 (1) | ||

| H10 | L | — | TP3 (1) | ||

| H11 | N | E3a | H3a | GEN, SXT | TP11 (1) |

| H12 | O | NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | No | ||

| H13 | P | SXT | TP3 (1) | ||

| H14 | Q | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | No | ||

| Ground chicken | |||||

| C1 | C | E2g | H2d | NAL, SXT, CHL | TP8 (1) |

| C2 | E | NAL, SXT, CHL | No | ||

| C3 to C11 | G | E1 | H1 | GEN, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP2 (7) |

| C12 | I | GEN, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | No | ||

| C13 | N | E3b | H3a | GEN, TOB, NAL, SXT | TP5 (1) |

| C14 | N | E3b | H3b | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP5 (1) |

| Chicken stool | |||||

| Cs1 | N | E3c | H3c | SXT, CHL | TP10 (1) |

| Ground pork | |||||

| P1 | N | E3e | H3c | GEN, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP9 (1) |

| Porcine stool | |||||

| Ps1 | C | E2a | H2a | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP1 (1) |

| Ps2 and Ps3 | C | E2a | H2a | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP4 (2) |

| Ps4 | C | E2b | H2b | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP3 (1) |

| Ps5 | C | E2d | H2e | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP3 (1) |

| Ps6 | H | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP3 (1) | ||

| Ps7 | K | GEN, TOB, NAL, LVX, CIP, SXT, CHL | TP5 (1) | ||

There were two or more band differences among different RAPD profiles. Isolates showing patterns that differed by a single band were considered minor variants of a given major group, but no minor variants were found.

The results were interpreted according to the criteria of Tenover et al. (19).

Susceptibilities to non-β-lactam agents were determined by the disk diffusion method. Antibiotics tested included gentamicin (GEN), tobramycin (TOB), nalidixic acid (NAL), levofloxacin (LVX), ciprofloxacin (CIP), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT), chloramphenicol (CHL), and amikacin. All isolates were susceptible to amikacin.

No, transconjugants were not obtained.

—, susceptible to all antibiotics tested.

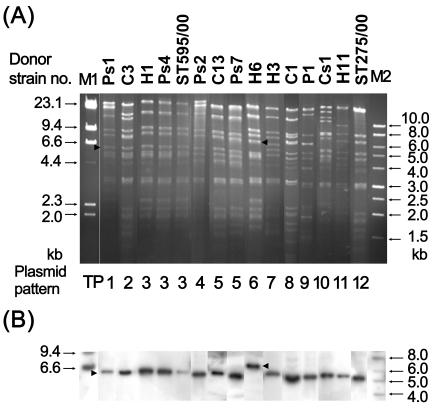

Eleven of the 14 human isolates and 19 of the 23 nonreplicate GMAS isolates transferred the blaCMY-2 gene to streptomycin-resistant E. coli C600 by the liquid mating-out assay as described previously (17, 25). All transconjugants displayed a pI 9.0 β-lactamase. The transferred plasmids extracted from these transconjugants were treated with the restriction endonuclease EcoRI (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and were then analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Two previously obtained E. coli transconjugants of CMY-2-producing Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains ST275/00 and ST595/00 (24) were included for comparison. Overall, the transferred plasmids gave 12 restriction patterns (Table 2 and Fig. 1A), and their sizes ranged from 70 to 110 kb. Pattern TP3 was shared by the transferred plasmids from seven human and three porcine stool isolates and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium strain ST595/00. This finding suggests the transmission of blaCMY-2 between enteric organisms in food animals and humans in Taiwan. The transferred plasmid from Salmonella serovar Typhimurium strain ST275/00 showed a unique pattern, pattern TP12. By Southern hybridization (18, 24), a 6.8-kb band hybridized to the α-32P-labeled blaCMY-2 probe in the EcoRI-restricted TP6 plasmids (Fig. 1B). All of the remaining restricted plasmids hybridized to the probe at a 5.2-kb band.

FIG. 1.

EcoRI restriction patterns of the representative transferred CMY-2-encoding plasmids (A) and Southern hybridization with a blaCMY-2 probe (B). Arrowheads indicate the locations of restriction fragments that were hybridized. Above each lane is the donor strain number. Strains ST595/00 and ST275/00 are two previously identified CMY-2-producing Salmonella strains (24). Lane M1, a 1-kb molecular marker; lane M2, molecular marker II (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

MICs of β-lactam agents were determined by the standard agar dilution method with E. coli ATCC 25922 as the quality reference strain (13). All CMY-2-producing E. coli isolates and their transconjugants showed elevated MICs of amoxicillin (≥128 μg/ml), amoxicillin-clavulanate (16 to 64 μg/ml), cefoxitin (≥64 μg/ml), ceftazidime (16 to 128 μg/ml), and cefotaxime (4 to 16 μg/ml). Susceptibilities to non-β-lactam agents for the CMY-2 producers were determined by the standard disk diffusion method (11, 12). The antibiotics tested and the susceptibility results are shown in Table 2. Notably, 6 of the 14 human isolates and 19 of the 23 GMAS isolates showed resistance to fluoroquinolones and at least two other non-β-lactam agents. The spread of such multidrug-resistant strains may cause significant therapeutic problems in animal and human health care in Taiwan.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grant NSC 92-2320-B-006-088 from the National Science Council, Taiwan, and grant NCKUH 92-46 from the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Taiwan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, K. J., and C. Poppe. 2002. Occurrence and characterization of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins mediated by β-lactamase CMY-2 in Salmonella isolated from food-producing animals in Canada. Can. J. Vet. Res. 66:137-144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbeit, R. D. 1999. Laboratory procedures for the epidemiologic analysis of microorganisms, p. 116-137. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 3.Bauernfeind, A., I. Stemplinger, R. Jungwirth, and H. Giamarellou. 1996. Characterization of the plasmidic β-lactamase CMY-2, which is responsible for cephamycin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:221-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauernfeind, A., H. Grimm, and S. Schweighart. 1990. A new plasmidic cefotaximase in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Infection 18:294-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush, K., G. A. Jacoby, and A. A. Medeiros. 1995. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1211-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carattoli, A., F. Tosini, W. P. Giles, M. E. Rupp, S. H. Hinrichs, F. J. Angulo, T. J. Barrett, and P. D. Fey. 2002. Characterization of plasmids carrying CMY-2 from expanded-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella strains isolated in the United States between 1996 and 1998. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1269-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fey, P. D., T. J. Safranek, M. E. Rupp, E. F. Dunne, E. Ribot, P. C. Iwen, P. A. Bradford, F. J. Angulo, and S. H. Hinrichs. 2000. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella infection acquired by a child from cattle. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1242-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grunstein, M., and D. S. Hogness. 1975. Colony hybridization: a method for the isolation of cloned DNAs that contain a specific gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:3961-3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manges, A. R., J. R. Johnson, B. Foxman, T. T. O'Bryan, K. E. Fullerton, and L. W. Riley. 2001. Widespread distribution of urinary tract infections caused by a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clonal group. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1007-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthew, M., M. Harris, M. J. Marshall, and G. W. Rose. 1975. The use of analytical isoelectric focusing for detection and identification of β-lactamases. J. Gen. Microbiol. 88:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 8th ed. Approved standard M2-A8. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 12.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Approved standard M100-S13. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 14.Pai, H., S. Lyu, J. H. Lee, J. Kim, Y. Kwon, J.-W. Kim, and K. W. Choe. 1999. Survey of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: prevalence of TEM-12 in Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1758-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Philippon, A., G. Arlet, and G. A. Jacoby. 2002. Plasmid-determined AmpC-type β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popovic, T., C. A. Bopp, Ø. Olsvik, and J. A. Kiehlbauch. 1993. Ribotyping in molecular epidemiology, p. 573-589. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 17.Provence, D. L., and R. Curtiss III. 1994. Gene transfer in gram-negative bacteria, p. 319-347. In P. Gerhardt, R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg (ed.), Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Southern, E. M. 1975. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J. Mol. Biol. 98:503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Versalovic, J., T. Koeuth, and J. R. Lupski. 1991. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6823-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White, D. G., S. Zhao, R. Sudler, S. Ayers, S. Friedman, S. Chen, P. F. McDermott, S. McDermott, D. D. Wagner, and J. Meng. 2001. The isolation of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella from retail ground meats. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1147-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winokur, P. L., A. Brueggemann, D. L. Desalvo, L. Hoffmann, M. D. Apley, E. K. Uhlenhopp, M. A. Pfaller, and G. V. Doern. 2000. Animal and human multidrug-resistant, cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella isolates expressing a plasmid-mediated CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2777-2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winokur, P. L., D. L. Vonstein, L. J. Hoffman, E. K. Uhlenhopp, and G. V. Doern. 2001. Evidence for transfer of CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase plasmids between Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals and humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2716-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan, J. J., W. C. Ko, C. H. Chiu, S. H. Tsai, H. M. Wu, and J. J. Wu. 2003. Emergence of ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella isolates and rapid spread of plasmid-encoded CMY-2-like cephalosporinase, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:323-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan, J. J., W. C. Ko, S. H. Tsai, H. M. Wu, Y. T. Jin, and J. J. Wu. 2000. Dissemination of CTX-M-3 and CMY-2 β-lactamases among clinical isolates of Escherichia coli in southern Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4320-4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao, S., D. G. White, P. F. McDermott, S. Friedman, L. English, S. Ayers, J. Meng, J. J. Maurer, R. Holland, and R. D. Walker. 2001. Identification and expression of cephamycinase blaCMY genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals and ground meat. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3647-3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]