Abstract

These NCCN Guidelines Insights highlight the important updates/changes specific to the management of metastatic breast cancer in the 2012 version of the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Breast Cancer. These changes/updates include the issue of retesting of biomarkers (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) on recurrent disease, new information regarding first-line combination endocrine therapy for metastatic disease, a new section on monitoring of patients with metastatic disease, and new information on endocrine therapy combined with an mTOR inhibitor as a subsequent therapeutic option.

Overview

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women in the United States and is second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death. The American Cancer Society (ACS) has estimated that 229,060 new cases of breast cancer will be diagnosed and 39,920 people will die of breast cancer in the United States in 2012.1 The therapeutic options for patients with noninvasive or invasive breast cancer are complex and varied. The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Breast Cancer include up-to-date guidelines for the clinical management of patients with carcinoma in situ, invasive breast cancer, Paget disease, Phyllodes tumor, inflammatory breast caner, and breast cancer during pregnancy (available at NCCN.org). These NCCN Guidelines Insights highlight the important updates/changes specific to the management of metastatic breast cancer in the 2012 version of the NCCN Guidelines for Breast Cancer. These include the issue of retesting of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in patients with recurrent disease; new information regarding first-line combination endocrine therapy for metastatic disease; a new section on monitoring of patients with metastatic disease; and new information on endocrine therapy combined with an mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor as a subsequent therapeutic option.

Retesting of Biomarkers on Recurrent Disease

Assessment of ER/PR and HER2 status in patients with breast cancer is clinically relevant when selecting patients eligible for endocrine and/or anti-HER2–based therapy. NCCN Task Forces and ASCO along with the College of American Pathologists (CAP) have issued quality-control recommendations on ER/PR testing2,3 and HER2 testing4,5 in patients with breast cancer.

Discordance between the receptor status of primary and recurrent disease has been reported in several studies. The discordance rates are in the range of 3.4% to 60% for ER-negative to ER-positive; 7.2% to 31% for ER-positive to ER-negative; and 0.7% to 10% for HER2.6–12 Discordance in receptor status between the primary tumor and recurrence may be a result of several factors, including a change in disease biology, differential effect of prior treatment on clonal subsets, tumor heterogeneity, and less-than-perfect accuracy and reproducibility of receptor and gene amplification assays.

The knowledge of a change in receptor status from negative in primary tumor to positive in metastatic disease can be beneficial to the therapeutic decision process in the metastatic setting, because effective, relatively nontoxic therapeutic options of endocrine therapy and/or HER2-targeted therapy become available. Retesting, however, carries with it the potential for denying a patient endocrine therapy/HER2-targeted therapy because of a false-negative result on a second biopsy. According to the NCCN Breast Cancer Panel, retesting the receptor status of recurrent disease is especially important in cases when it was previously unknown, originally negative, or not overexpressed. Clinical judgment remains important. For patients with clinical courses consistent with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, or with prior positive hormone receptor results, the panel agreed that a course of endocrine therapy is reasonable regardless of whether the receptor assay is repeated or is the result of the most recent hormone receptor assay.

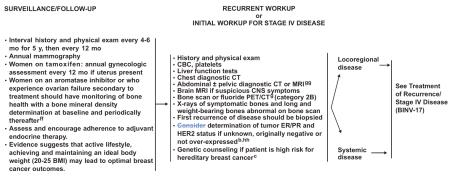

NCCN Recommendations

The NCCN Breast Cancer Panel recommends that metastatic disease at presentation or first recurrence of disease be biopsied as part of the workup for patients with recurrent or stage IV disease (see BINV-16; on page 822). This ensures accurate determination of metastatic/recurrent disease and tumor histology, and allows for biomarker determination and selection of appropriate treatment. The status of the tumor biomarkers ER/PR and HER2 should be determined if unknown, originally negative, or not overexpressed (category 2A). The panel cautions in a footnote that “false negative ER and/or PR determinations occur, and there may be discordance between the ER and/or PR determination between the primary and metastatic tumor(s). Therefore, endocrine therapy with its low attendant toxicity may be considered in patients with non-visceral or asymptomatic visceral tumors, especially in patients with clinical characteristics predicting for a hormone receptor positive tumor (e.g., long disease free interval, limited sites of recurrence, indolent disease, or older age).”

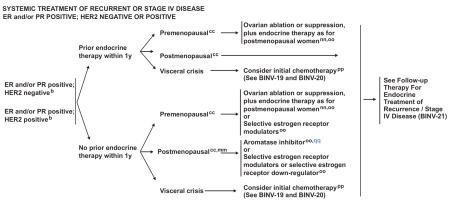

Combination Endocrine Therapy An Option for First-Line Treatment

Combination endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive, previously untreated metastatic breast cancer has been reported in 2 studies comparing single-agent anastrozole versus anastrozole plus fulvestrant. In the first study (FACT trial), combination endocrine therapy was not superior to single-agent anastrozole (time to progression hazard rate, 0.99; 95% Cl, 0.81–1.20; P = .91).13 In the second study (S0226), the progression-free survival (hazard rate, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.68–0.94, stratified log-rank P = .007) and overall survival (hazard rate, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.65–1.00; stratified P = .049) were superior with combination anastrozole plus fulvestrant.14 An unplanned subset analysis of this trial suggested that patients without prior adjuvant tamoxifen experienced the greatest benefit with the combination endocrine therapy. The reason for the divergent outcomes in the 2 studies is not known.

NCCN Recommendations

Because of the contradictory results of the FACT13 and S022614 trials, the NCCN Breast Cancer Panel has not made specific recommendations for including combination endocrine therapy in the main algorithm of the guidelines. However, the panel included a footnote on algorithm page BINV-18 (see page 823) stating, “A single study (S0226) in women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer and no prior chemotherapy, biological therapy, or endocrine therapy for metastatic disease demonstrated that the addition of fulvestrant to anastrozole resulted in prolongation of time to progression (hazard rate for recurrence, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.68–0.94; stratified log-rank P =.007) and improvement in overall survival (hazard rate, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.65–1.00; stratified log-rank P = .049). Subset analysis suggested that patients without prior adjuvant tamoxifen and more than 10 years since diagnosis experienced the greatest benefit. A study of similar design (FACT) demonstrated no advantage in time to progression with the addition of fulvestrant to anastrozole (hazard rate, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.81–1.20; P = .91).”

Monitoring of Metastatic Disease

Very little high-level evidence exists on monitoring patients with metastatic breast cancer during the course of disease and treatment. Monitoring patients with metastatic disease is extremely important to determine whether the therapy administered is effective. Monitoring of disease activity during treatment helps ensure that the patient does not experience toxicity from an ineffective therapy. The panel included a new section in the 2012 version of the guidelines titled “Principles of Metastatic Disease Monitoring.” This section includes a discussion and recommendations on how metastatic disease should be monitored. The monitoring recommendations primarily reflect those from the prospective clinical trials on which the current treatment decisions are based.

NCCN Recommendations

In the new section “Principles of Monitoring of Metastatic Disease” (see BINV-M; on pages 824–826, the panel first stressed the importance of monitoring metastatic disease, and has provided the definition of progression of disease and outlined a series of components of monitoring that includes periodic assessment of symptoms, physical examination, routine laboratory tests, imaging studies, and, where appropriate, use of blood biomarkers (see BINV-M 1 of 3; on page 824). The panel acknowledges that, although integration of all of these components is important, in practice it can be challenging because the information obtained may be contradictory. Therefore, prudent clinical judgement is important to negotiate the differences in these cases.

The panel recommends objective criteria for assessing disease response, stable disease, and disease progression (see BINV-M 2 of 3; on page 825), and specifically encourages using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)15 or WHO criteria16 as a system for assigning disease activity.

The panel acknowledges the challenges of functional imaging, such as bone or PET/CT scans. These specific imaging studies monitor biologic function of the tumor as opposed to size of the tumor as the end point. With bone scan, responding disease may show a “flare,” or as increased activity, which may be easily misinterpreted as disease progression. The main challenge with using PET/CT scanning to monitor metastatic disease is that there is an absence of a reproducible, validated, and widely accepted set of standards for disease activity assessment. According to RECIST criteria, only progression of disease can be assessed with PET scan when a new site of PET abnormality occurs. In no other instances do the WHO or RECIST criteria allow use of PET/CT scan to declare response, disease stability, or disease progression.

The panel has provided a table outlining general recommendations for the frequency and type of monitoring as a baseline before initiation of new therapy and for monitoring the effectiveness of cytotoxic chemotherapy, monitoring the effectiveness of endocrine therapy, and assessment in the presence of evidence of disease progression. They have indicated in a footnote that the frequency of monitoring can be reduced in patients who have long-term stable disease.

Endocrine Therapy Plus an mTOR Inhibitor: A Subsequent Therapy Option

Resistance to endocrine therapy in women with hormone receptor–positive disease is frequent. One mechanism of endocrine resistance is activation of the mTOR signal transduction pathway. Two randomized studies have investigated the use of aromatase inhibition in combination with inhibitors of the mTOR pathway.

A phase III study (BOLERO-2) in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer that had progressed or recurred during treatment with a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor randomized patients to exemestane with or without the mTOR inhibitor everolimus.17 The results of this study showed the median progression-free survival was increased with the addition of everolimus to exemestane from 2.8 to 6.9 months (hazard ratio, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.35–0.54; log-rank P < .001).17 The results also showed that the toxicity of combination exemestane and everolimus was substantially greater than exemestane alone. The most common all-grade adverse events in patients who received everolimus versus those who did not included stomatitis (56% vs. 11%), rash (36% vs. 6%), fatigue (33% vs. 26%), diarrhea (30% vs. 16%), decreased appetite (29% vs. 10%), noninfectious pneumonitis (12% vs. 0%), and hyperglycemia (13% vs. 2%).17 Thus, in this study, the addition of everolimus prolonged time to progression but it also added substantial toxicity. No survival data have yet been reported.

Another trial phase III trial randomized postmenopausal women with advanced, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer with no prior endocrine therapy to letrozole with or without the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus.18 In this study, progression-free survival was not different between the treatment arms (hazard rate, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.75–1.05; long-rank P = .18).

The reasons for the difference in the outcomes of the 2 endocrine therapy with or without an mTOR inhibitor studies are uncertain, but may be related to the issues of patient selection, or the type and extent of prior endocrine therapy. A footnote has been added to the guidelines that lists subsequent endocrine therapy for systemic disease.

NCCN Recommendations

The panel unanimously agreed that the evidence from the BOLERO-2 trial is compelling enough to consider the addition of everolimus to exemestane in women who fulfill the entry criteria for BOLERO-2.

On the page in the algorithm listing subsequent endocrine therapy for patients (see BINV-N; on page 827), the panel added a footnote stating “A single study (BOLERO-2) in women with hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer and prior therapy with a non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor demonstrated improvement in time to progression with the addition of everolimus (an mTOR inhibitor) to exemestane (hazard rate, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.36–0.53; log-rank P = <1 x10−16) and with increase in toxicity. No survival analysis is available. A randomized study using the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus in combination with endocrine therapy did not demonstrate any improvement in outcome. Consider the addition of everolimus to exemestane in women who fulfill the eligibility criteria of BOLERO-2.”

Conclusions

These NCCN Guidelines Insights highlight the important updates/changes specific to the management of metastatic breast cancer in the 2012 version of the NCCN Guidelines for Breast Cancer (to view the most recent version of these guidelines, visit NCCN.org). The NCCN Guidelines are in continuous evolution. They are updated annually, or sometimes more often if new high-quality clinical data become available in the interim. The recommendations in the NCCN Guidelines, with few exceptions, are based on evidence from clinical trials. Expert medical clinical judgment is required to apply these guidelines in the context of an individual to provide optimal care. The physician and the patient have the responsibility to jointly explore and select the most appropriate option from among the available alternatives. When possible, consistent with NCCN philosophy, the panel strongly encourages patient/physician participation in prospective clinical trials.

BINV-16.

bSee Principles of HER2 Testing (BINV-A).

cSee NCCN Genetics/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian Guidelines.

gIf FDG PET/CT are performed and both clearly indicate bone metastases, bone scan or fluoride PET/CT may not be needed.

ffThe use of estrogen, progesterone, or selective estrogen receptor modulators to treat osteoporosis or osteopenia in women with breast cancer is discouraged. The use of a bisphosphonate is generally the preferred intervention to improve bone mineral density. Optimal duration of bisphosphonate therapy has not been established. Factors to consider for duration of anti-osteoporosis therapy include bone mineral density, response to therapy, and risk factors for continued bone loss or fracture. Women treated with a bisphosphonate should undergo a dental examination with preventive dentistry prior to the initiation of therapy, and should take supplemental calcium and vitamin D.

ggThe use of PET or PET/CT scanning should generally be discouraged for the evaluation of metastatic disease except in those clinical situations where other staging studies are equivocal or suspicious. Even in these situations, biopsy of equivocal or suspicious sites is more likely to provide useful information.

hhFalse-negative ER and/or PR determinations occur, and there may be discordance between the ER and/or PR determination between the primary and metastatic tumor(s). Therefore, endocrine therapy with its low attendant toxicity may be considered in patients with non-visceral or asymptomatic visceral tumors, especially in patients with clinical characteristics predicting for a hormone receptor-positive tumor (eg, long disease-free interval, limited sites of recurrence, indolent disease, older age).

Version 1.2012 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2012, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN®.

BINV-18.

bSee Principles of HER2 Testing (BINV-A).

ccDefinition of Menopause (BINV-L).

mmLimited studies document a progression-free survival advantage of adding trastuzumab or lapatinib to aromatase inhibition in postmenopausal patients with ER-positive, HER2-positive disease. However, no overall survival advantage has been demonstrated.

nnSee Subsequent Endocrine Therapy (BINV-N).

ooIt is unclear that women presenting at time of initial diagnosis with metastatic disease will benefit from the performance of palliative local breast surgery and/or radiation therapy. Generally this palliative local therapy should be considered only after response to initial systemic therapy.

ppSee Preferred Chemotherapy Regimens for Recurrent or Metastatic Breast Cancer (BINV-O).

qqA single study (S0226) in women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer and no prior chemotherapy, biological therapy, or endocrine therapy for metastatic disease demonstrated that the addition of fulvestrant to anastrozole resulted in prolongation of time to progression (Hazard rate for recurrence 0.80; 95% CI 0.68 – 0.94; stratified log-rank p=0.007) and improvement in overall survival (hazard rate 0.81; 95% CI 0.65 – 1.00; stratified log-rank p = 0.049). Subset analysis suggested that patients without prior adjuvant tamoxifen and more than 10 years since diagnosis experienced the greatest benefit. A study of similar design (FACT) demonstrated no advantage in time to progression with the addition of fulvestrant to anastrozole (Hazard rate 0.99; 95% CI 0.81–1.20; p=0.91).

Version 1.2012 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2012, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN®.

BINV-M 1 of 3.

PRINCIPLES OF MONITORING METASTATIC DISEASE

Monitoring of patient symptoms and cancer burden during treatment of metastatic breast cancer is important to determine whether the treatment is providing benefit and that the patient does not have toxicity from an ineffective therapy.

Components of Monitoring

Monitoring includes periodic assessment of varied combinations of symptoms, physical examination, routine laboratory tests, imaging studies, and where appropriate blood biomarkers. Results of monitoring are classified as response / continued response to treatment, stable disease, uncertainty regarding disease status or progression of disease. The clinician typically must assess and balance multiple different forms of information to make a determination regarding whether disease is being controlled and the toxicity of treatment is acceptable. Sometimes, this information may be contradictory

Definition of Disease Progression

Unequivocal evidence of progression of disease by one or more of these factors is required to establish progression of disease, either because of ineffective therapy or acquired resistance of disease to an applied therapy. Progression of disease may be identified through evidence of growth or worsening of disease at previously known sites of disease and/or of the occurrence of new sites of metastatic disease.

- Findings concerning for progression of disease include:

-

➤Worsening symptoms such as pain or dyspnea

-

➤Evidence of worsening or new disease on physical examination

-

➤Declining performance status

-

➤Unexplained weight loss

-

➤Increasing alkaline phosphatase, ALT, AST, or bilirubin

-

➤Hypercalcemia

-

➤New radiographical abnormality or increase in the size of pre-existing radiographic abnormality

-

➤New areas of abnormality on functional imaging (eg, bone scan, PET/CT scan)

-

➤Increasing tumor markers (eg, CEA, CA15-3, CA27.29)1

-

➤

1Rising tumor markers (eg, CEA, CA15-3, CA27.29) are concerning for tumor progression, but may also be seen in the setting of responding disease. An isolated increase in tumor markers should rarely be used to declare progression of disease. Changes in bone lesions are often difficult to assess on plain or cross-sectional radiology, or on bone scan. For these reasons, patient symptoms and serum tumor markers may be more helpful in patients with bone-dominant metastatic disease.

Version 1.2012 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2012, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN®.

BINV-M 2 of 3.

PRINCIPLES OF MONITORING METASTATIC DISEASE

Use of Objective Criteria for Response / Stability / Progression

The most accurate assessments of disease activity typically occur when previously abnormal studies are repeated on a serial and regular basis. Generally, the same method of assessment should be used over time – e.g. an abnormality found on chest CT scan should generally be monitored with repeat chest CT scans.

Some non-clinically important variation in measurement of abnormalities by all serial studies is common and expected. Therefore, the use of objective and widely accepted criteria for response, stability, and progression of disease are encouraged. Such systems include the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) guideline (Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–247) and the WHO criteria (Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M and Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer 1981;47:207–214)

Studies of functional imaging, such as radionuclide bone scans and PET imaging are particularly challenging when used to assess response. In the case of bone scans, responding disease may result in a flare or increased activity on the scan that may be misinterpreted as disease progression, especially on the first follow-up bone scan after initiating a new therapy. PET imaging is challenging because of the absence of a reproducible, validated, and widely accepted set of standards for disease activity assessment.

Frequency of Monitoring

The optimal frequency of repeat testing is uncertain, and is primarily based upon the monitoring strategies utilized in breast cancer clinical trials. The frequency of monitoring must balance the need to detect progressive disease, avoid un-necessary toxicity of any ineffective therapy, resource utilization, and cost. The following table is to provide guidance, and should be modified for the individual patient based upon sites of disease, biology of disease, length of time on treatment, etc. Reassessment of disease activity should be performed in patients with new or worsening signs or symptoms of disease, regardless of the time interval from previous studies.

Version 1.2012 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2012, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN®.

BINV-M 3 of 3.

PRINCIPLES OF MONITORING METASTATIC DISEASE

| Suggested intervals of follow-up for patients with metastatic disease1 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Baseline prior to new therapy | Chemotherapy | Endocrine therapy | Restaging if concern for progression of disease | |

|

| ||||

| Symptom assessment | Yes | Prior to each cycle | Every 2–3 months | Yes |

|

| ||||

| Physical examination | Yes | Prior to each cycle | Every 2–3 months | Yes |

|

| ||||

| Performance status | Yes | Prior to each cycle | Every 2–3 months | Yes |

|

| ||||

| Weight | Yes | Prior to each cycle | Every 2–3 months | Yes |

|

| ||||

| LFTs, CBC | Yes | Prior to each cycle | Every 2–3 months | Yes |

|

| ||||

| CT scan chest/abd/pelvis | Yes | Every 2–4 cycles | Every 2–6 months | Yes |

|

| ||||

| Bone scan | Yes | Every 4 cycles | Every 4–6 months | Yes |

|

| ||||

| PET/CT | Optional | Unknown | Unknown | Optional |

|

| ||||

| Tumor markers | Optional | Optional | Optional | Optional |

|

| ||||

| 1 In patients who have long-term stable disease, the frequency of monitoring can be reduced. | ||||

Version 1.2012 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2012, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN®.

BINV-N.

SUBSEQUENT ENDOCRINE THERAPY FOR SYSTEMIC DISEASE

Premenopausal patients with ER-positive disease should have ovarian ablation/suppression and follow postmenopausal guideline

POSTMENOPAUSAL PATIENTS

Non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor (anastrozole, letrozole)

Steroidal aromatase inactivator (exemestane)1

Fulvestrant

Tamoxifen or Toremifene

Megestrol acetate

Fluoxymesterone

Ethinyl estradiol

1A single study (BOLERO-2) in women with hormone receptor-positive, HER-2 negative metastatic breast cancer and prior therapy with a non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor demonstrated improvement in time to progression with the addition of everolimus (an mTOR inhibitor) to exemestane (Hazard rate 0.44; 95% CI 0.36–0.53; log-rank P = <1 × 10–16) and with an increase in toxicity. No survival analysis is available. A randomized study using the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus in combination with endocrine therapy did not demonstrate any improvement in outcome. Consider the addition of everolimus to exemestane in women who fulfill the eligibility criteria of BOLERO-2.

Version 1.2012 © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2012, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN®.

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

-

Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

Footnotes

Disclosures for the NCCN Breast Cancer Panel Individual disclosures of potential conflicts of interest for the NCCN Breast Cancer Panel members can be found online at NCCN.org.

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. The NCCN Guidelines® Insights highlight important changes in the NCCN Guidelines® recommendations from previous versions. Colored markings in the algorithm show changes and the discussion aims to further understanding of these changes by summarizing salient portions of the Panel's discussion, including the literature reviewed.

The NCCN Guidelines Insights do not represent the full NCCN Guidelines; further, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding the content, use, or application of the NCCN Guidelines and NCCN Guidelines Insights and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way.

The full and most current version of these NCCN Guidelines is available at NCCN.org.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allred DC, Carlson RW, Berry DA, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor testing in breast bancer by immunohistochemistry. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(Suppl 6):S1–21. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2784–2795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson RW, Moench SJ, Hammond ME, et al. HER2 testing in breast cancer: NCCN Task Force report and recommendations. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4(Suppl 3):S1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogina G, Bortesi L, Marconi M, et al. Comparison of hormonal receptor and HER-2 status between breast primary tumours and relapsing tumours: clinical implications of progesterone receptor loss. Virchows Arch. 2011;459:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabi A, Di Benedetto A, Metro G, et al. HER2 protein and gene variation between primary and metastatic breast cancer: significance and impact on patient care. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2055–2064. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson E, Lindström LS, Wilking U, et al. Discordance in hormone receptor status in breast cancer during tumor progression [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl) Abstract 1009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sari E, Guler G, Hayran M, et al. Comparative study of the immunohistochemical detection of hormone receptor status and HER-2 expression in primary and paired recurrent/metastatic lesions of patients with breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2011;28:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simmons C, Miller N, Geddie W, et al. Does confirmatory tumor biopsy alter the management of breast cancer patients with distant metastases? Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1499–1504. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong Y, Booser DJ, Sneige N. Comparison of HER-2 status determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization in primary and metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1763–1769. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapia C, Savic S, Wagner U, et al. HER2 gene status in primary breast cancers and matched distant metastases. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R31. doi: 10.1186/bcr1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergh J, Jönsson P, Lidbrink E, et al. First results from FACT – an open-label, randomized phase III study investigating loading dose of fulvestrant combined with anastrozole versus anastrozole at first relapse in hormone receptor positive breast cancer [abstract] Cancer Res. 2009;69(24 Suppl) Abstract 23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta R, Barlow W, Albain K, et al. A Phase III randomized trial of anastrozole versus anastrozole and fulvestrant as first-line therapy for postmenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer: SWOG S0226 [abstract]. Presented at the 34th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, Texas. December 6–10, 2011; Abstract 1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47:207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::aid-cncr2820470134>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:520–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chow L, Sun Y, Jassem J, et al. Phase 3 study of temsirolimus with letrozole or letrozole alone in postmenopausal women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer [abstract]. Presented at the 29th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, Texas. December 14–17, 2006; Abstract 6091. [Google Scholar]