Abstract

Many aspects of patients’ experiences with illness, medication, and health care are best captured from patient-reported outcomes (PROs). In this article, we describe the process for constructing quality PRO instruments, from conceptual model development through instrument validation. We also discuss PROs as clinical trial end points and the potential of PRO data for aiding clinicians and patients in choosing from among multiple therapeutic options. Finally, we provide an overview of some existing PRO instruments.

WHAT ARE PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOMES?

A PRO is “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”1 PROs provide patients’ perspectives on their well-being, functioning, symptoms, and experiences with treatment. The use of PROs has become increasingly prevalent in clinical research, reflecting the growing recognition that patient quality of life is an important outcome.2 The growth in the use of PROs has also been fueled by the development of combination and targeted therapies that produce a variety of side effects best captured by direct patient input.3 For concepts such as pain, fatigue, emotional distress, satisfaction with care, and impact of symptoms on participation in meaningful activities, patients are the best source of information. Among patients with identical clinical presentations (e.g., hemoglobin levels or tumor characteristics) there may be wide variations in symptoms, side effects, and functional status.

HOW ARE PRO MEASURES DEVELOPED?

Before developing a new PRO instrument, it is beneficial to review existing measures in the area of interest. Given the proliferation of PRO measures, the development of an entirely new measure might be unnecessary; it may be sufficient to modify an existing measure or collect new clinical validation data. This approach increases opportunities for comparison of results through the shared use of a PRO.

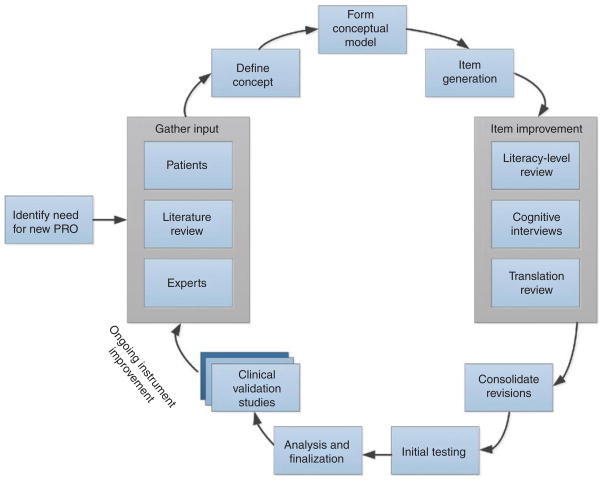

If a new measure is necessary, a high-quality instrument can be developed using mixed qualitative and quantitative methods. Figure 1 illustrates the process used to develop a PRO measure. The first aim is to develop an appropriate conceptual model. This is done by narrowing the broader theoretical model to include only the specific components and their possible causal linkages of interest.4,5 Describing the precise manner in which the concept of interest is associated with other clinical trial assessments is also useful.6 The specific concept(s) of interest should be defined with careful attention to its core characteristics and boundaries. For example, if an investigator is interested in pain, the concept definition would help identify the specific components of pain (e.g., intensity, quality, variability) of interest and those that are outside the scope (e.g., responsiveness to analgesic medication, beliefs about etiology of pain). The assistance of experts in the collection of qualitative data from patients is useful in construct definition and model creation for the purpose of building in content validity.7 Domain experts (e.g., oncologists treating cancer pain) can provide information about the components of the construct that are most important clinically and are shared across patients. Patient input can be procured through individual interviews and/or focus groups that allow for capturing a range of unobservable patient experiences such as thoughts, feelings, intentions, and past behaviors. Patients can identify important co mponents of the construct of interest and describe their experiences in lay language. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims1 highlights the importance of including substantial patient input in PRO development.

Figure 1.

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument development process.

A comprehensive review of the literature8 can reveal the manner in which a particular concept has been previously assessed. Analysis of existing measures can inform development of a new measure by identifying relevant ideas captured in items, conventions of recall period (“time frame respondents instructed to refer to in answering questions”),9 and response options (e.g., intensity or frequency of symptoms) that may best discriminate between patients. By reviewing existing items and processing newly captured qualitative data, item construction can begin. Each item should reflect a single idea. For example, asking about nausea and vomiting in one question produces confusion for a patient who has one symptom but not the other. The recall period should be appropriate for the construct and the intended use of the instrument.10 Some items may tax a patient’s memory or require a response about an experience that was not committed to memory at the time. The recall period should be long enough to sample the desired experience (e.g., participation in leisure activities) but short enough to capture change during the course of a clinical trial. Attributions (e.g., “Because of my illness…”) may or may not be appropriate for a given construct because the accuracy of patients’ understanding of the etiology of a symptom may vary.

Where possible, items should be presented in a plain, easy-to-read format. The National Assessment of Adult Literacy found that 14% of Americans have low literacy and 22% have only basic literacy, suggesting that significant numbers of patients in a clinical trial may have limitations in reading and responding to PRO questionnaires.11 Given that translation of PRO instruments is expected, it is useful to review items during development for issues that could pose difficulties during translation into other languages (e.g., verb tenses, units of measure, and idioms). Modification during development aids not only future translations but also understandability in the original language.

Following initial instrument development, cognitive interviews, i.e., “think aloud” interviews, are a useful tool for assessing the clarity and importance of items for patients.7 Cognitive interviews typically involve a participant completing a measure and answering questions aimed at soliciting his or her interpretation of the item and the thought process in selecting a response. This allows researchers to assess whether patients’ understanding of an item is the same as that of the instrument developers, whether the response options suit a specific question, and whether issues of literacy, jargon, technical language, or culture-specific constructs exist. Cognitive interviews are conducted until no new information is gained from additional interviews (saturation). Item revisions are then implemented to address the identified problems.

Initial testing within populations of interest is conducted to compare the new instrument with existing PROs. Reliability (including the ability of an instrument to produce reproducible, stable scores in the same individuals under the same conditions, and the precision with which the instrument measures a construct)12 is assessed, as well as floor/ceiling effects (e.g., an instrument’s ability to assess extremes of the construct). Knowledge of an instrument’s floor/ceiling effects can help users choose the appropriate instrument for use in a particular sample of participants or for specific study aims. For example, for assessing mild pain, an instrument capable of detecting lower levels of pain (i.e., an instrument with a low floor) would be most appropriate. Analyses should address variability in participant responses because items with little variability in the responses evoked are not useful in discriminating between patients. Validity is assessed in a variety of ways, including demonstration of moderate to high correlations with existing measures that address the same concept (convergent validity), low correlations with measures that assess other concepts (divergent validity), and responsiveness to meaningful change (Do scores on the measure change when expected to do so and remain stable when no change is expected?). Both cross-sectional sensitivity (i.e., the ability to show differences between groups at any given time point) and longitudinal sensitivity (i.e., the ability to show change in a given group across time points) are assessed. Additional clinical validation is an ongoing process that is never complete—an instrument is never “valid” in any unqualified sense. Validation is a process of building a case that an instrument functions effectively in a particular population for a specific purpose.

In addition to the ongoing accumulation of clinical validation data, high-quality PRO measures are reviewed and revised over their life spans to address changes in language and patient experience. For example, an item that assesses cognitive skills and seeks information about the patient’s ability to make a phone call may need to be revised to specify use of a traditional land-line phone vs. a graphic interface on a smartphone, given that these tasks involve different cognitive demands.

PROs IN CLINICAL TRIALS

In clinical trials, PROs provide a means for formal and systematic gathering of the patient’s perspectives with respect to symptoms, functioning, and quality of life under a particular treatment. When used correctly, PRO data can support a medical product labeling claim. In its guidance on the topic,1 the FDA specifies that PRO data can be used to support a medical product labeling claim when the PRO instrument is well defined, reliable, and used in accordance with the instrument’s documented measurement capability. The PRO instrument must be shown to be valid in the target patient population. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) guidance on PRO use applies to health-related quality of life, which the agency defines as a subset of PROs. Health-related quality of life differs from other PROs in that it is multidimensional; it assesses the impact of disease and treatment on multiple aspects of a patient’s functioning and well-being. The EMA considers patient reports of disease symptoms such as pain to be acceptable primary and second end points.

The FDA guidance recommends the use of an end-point model to define the role of the PRO in the clinical trial and to place the PRO end point in the larger trial context. Trial design and analysis follow a predefined plan that considers end points in relation to one another. For example, an end-point model may identify a physiological response (such as tumor progression) as the primary end point and fatigue as a secondary end point. If the trial succeeds on the primary end point, the PRO data could provide important information on patient symptoms that could aid clinical decision making. PROs can also function as primary end points; a PRO appeared as a clinical trial primary end point in a major medical journal as early as 1986.13 PROs are appropriate primary end points in clinical trials that aim to improve patient symptoms, functional status, or quality of life.14

In many therapeutic areas it is well established that PROs have added value over and above traditional clinical or laboratory test outcomes. PROs frequently appear on labels for anti-inflammatory and antimigraine agents, asthma and allergy medications, and gastrointestinal agents.2 In these areas, it is well recognized that patient input is critical for assessing therapeutic benefit. However, PRO measures are underutilized in some therapeutic areas.2,14 For example, although cardiovascular trials published in high-quality journals are increasingly reporting PROs, approximately two-thirds of cardiovascular trials in which PROs were judged to be relevant and important failed to report them.14 Many trials that focused on relief of symptoms or improvements in quality of life—areas in which patient input is essential—either did not report PROs or reported them only as nonprimary outcomes, thereby limiting their impact with respect to clinical decision making. Additional work is therefore needed to identify areas in which PROs could add value to trial outcomes. According to the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Outcomes Measurement Working Group, health-related quality of life measures provide added value when they aid interpretation of a study’s findings and influence clinical recommendations.15 For diseases such as renal cell carcinoma, new targeted therapies have improved prognosis. However, choosing between available drugs that vary in their side-effect profiles offen means weighing the impact of a drug on quality of life. PROs can provide clinicians and physicians with important patient input on quality of life that can guide treatment choices.16 Other barriers that have precluded the use of PROs include entrenched traditions in clinical practice, misperceptions about the value of PRO measures, and the restricted availability of good measures.2 Ongoing assessments of PRO use in clinical trials are needed to determine the optimal instruments for use across studies and identify diseases for which appropriate instruments are lacking.17

WHICH PRO MEASURES ARE AVAILABLE?

Many reliable and valid PRO measures are available. One type of measure, that of generic health status, allows for assessment of individuals with or without a medical condition (e.g., Short Form 36 from the Medical Outcomes Study18). This type of measure can provide population norms and benchmarks for comparing groups, such as those with and without a particular condition or across conditions. Additionally, they allow for evaluations of different interventions or disease characteristics. Beyond global health status, these instruments (e.g., the Sickness Impact Profile19) offen assess a patient’s perception of functioning or disability.

Preference or utility measures (e.g., EQ-5D; the Health Utilities Index20) also provide a summed score on a single dimension that can be compared with established population mean values. Preference measures, directly or indirectly obtained, express the value one places on his or her health in terms of a utility score. These scores range from 0 (representing a value equal to death) to 1.0 (representing perfect health). The value of a period of time survived can then be weighted by multiplying survival time by the utility coefficient. These measures are all preference-based and commonly used in economic analyses.

Some PRO measures have been developed for specific treatments, conditions, or symptoms. For example, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)21 measurement system includes therapy-specific instruments such as the FACT-EGFRI22 for patients receiving epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. FACIT also contains disease-specific instruments such as the FACT-P23 (for patients with prostate cancer) and symptom-specific instruments (e.g., FACIT-Fatigue24). These instruments provide a more complete assessment for a specific condition, treatment, or symptom.

REGULATORY APPROVAL CHALLENGES

To our knowledge, since the release of the FDA Draft PRO Guidance in 2006, no PRO label claim based on assessment using a PRO instrument has been favorably reviewed by the agency’s Study Endpoints and Label Development (SEALD) group. However, there are several examples of FDA approvals that include PRO label claims based on the use of PRO instruments. For example, the approval of imatinib (Gleevec) for chronic myelogenous leukemia included the FACT-BRM scale data on the safety side of the label. More recently, eculizumab (Soliris) was approved with a label claim including fatigue as measured by the FACIT-Fatigue.25,26

NEXT-GENERATION PROs

As the use of PROs proliferated, greater attention was placed on addressing variations in instrument quality, inability to compare results across instruments, and patient burden from long assessments. The Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System, or PROMIS (http://www.nihpromis.org), was launched in 2005 through a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Roadmap Initiative to address these issues. PROMIS aims to provide clinicians and researchers access to efficient, precise, and valid PRO measures. PROMIS utilizes rigorous qualitative and quantitative methods, including construct definitions, literature reviews, input from experts and focus groups, literacy and translation reviews, and cognitive interviews.9 Additionally, PROMIS addresses issues of accessibility for patients with visual, motor, and reading impairments so as to maximize participation in clinical research.27 Intellectual property issues were resolved to ensure that PROMIS measures are freely available to the clinical research community. By using the same measures across studies,28 PROMIS offers opportunities for comparison of results across studies and easier compilation of data sets.

PROMIS harnesses item response theory and computer technology to create and validate item banks for specific domains. An item bank is a collection of items assessing a single underlying trait (e.g., fatigue), with each item representing a point on the trait continuum. Item banks can be administered in multiple ways, including as a Computerized Adaptive Test (CAT) or through questionnaire forms of varying lengths. A CAT utilizes an item selection and scoring algorithm. After each response, a score estimate is calculated and the next item is selected based on the item in the bank that provides the most information at that range of the trait. For example, if a patient reports having difficulty walking for 100 yards or meters, the next question would focus on less difficult activities (e.g., walking 50 yards/meters) rather than asking about ability to jog 2 miles. CATs maximize precision while minimizing patient burden. Short forms constructed from item banks allow administration of maximally informative items while also covering specific components of the construct (e.g., both upper- and lower-extremity functioning). Item banks are more amenable to adaptation over time through addition and removal of items or item recalibration because retention of the core bank reduces the need to complete entirely new clinical validation efforts. Scores can remain on the same metric so as to facilitate comparisons between the original and revised versions of the item bank.

Psychometric and statistical analyses of PROMIS instruments were conducted after large-scale testing in a sample representative of the US general population (based on Census figures for the year 2000) and selected clinical samples (e.g., heart disease, cancer, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, spinal cord injury, and psychiatric illness).29 Across domains, PROMIS measures demonstrated good reliability (score precision) for scores between the mean and 2 or more standard deviations worse than the mean. Content validity was demonstrated through moderate to strong correlations between PROMIS and commonly used and accepted PRO instruments. PROMIS scores were generally worse for individuals with chronic conditions than for those without chronic conditions.30 Moreover, individuals who reported limitations due to a condition produced worse scores than those who were not experiencing limitations. The negative impact of disease on a given domain varied across conditions, and most conditions demonstrated multiple affected domains.

Additional analyses addressed differential item functioning and minimally important differences. Differential item functioning refers to a given item behaving differently between specific groups such as men and women or seniors and nonseniors. Items found to have differential item functioning were eliminated from the item bank to improve applicability of the bank across the widest range of potential study participants.31 Minimally important differences allow guidance on the extent of change in score or difference between group scores that is clinically meaningful, not merely statistically significant.32 Using multiple methods within a cancer sample, a change of 3 to 6 points was determined to be clinically meaningful.33 Minimally important differences can therefore help interpret change scores by providing a benchmark for assessing the magnitude of the effect.

PROMIS measures of physical, emotional, and social health (see Table 1) are available through Assessment Center (http://www.assessmentcenter.net). Measures are available for adults, children (ages 8–18), and parent proxies (parents who complete a measure for children aged 5–18). The PROMIS item banks were translated into Spanish utilizing a rigorous translation methodology.34 Translations into other languages are in process (see http://www.nihpromis.org/measures/translations). Additional item bank development and continued clinical validation efforts are ongoing through NIH PROMIS funding.

Table 1.

PROMIS instruments

| Domain | Adult | Pediatric | Parent proxy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional distress—anger | X | X | X |

| Emotional distress—anxiety | X | X | X |

| Emotional distress—depression | X | X | X |

| Applied cognition—abilities | X | — | — |

| Applied cognition—general concerns | X | — | — |

| Psychosocial illness impact—positive | X | — | — |

| Psychosocial illness impact—negative | X | — | — |

| Fatigue | X | X | X |

| Pain—behavior | X | — | — |

| Pain—intensity | X | — | — |

| Pain—interference | X | X | X |

| Pain—quality | X | — | — |

| Physical function (including adaptation for samples with mobility-aid users) | X | — | — |

| Mobility | — | X | X |

| Upper extremity | — | X | X |

| Sleep disturbance | X | — | — |

| Sleep-related impairment | X | — | — |

| Sexual function: global satisfaction with sex life, interest in sexual activity, lubrication, vaginal discomfort, erectile function, orgasm, therapeutic aids, sexual activities, anal discomfort, interfering factors | X | — | — |

| Satisfaction with social roles and activities (including discretionary social activities) | X | — | — |

| Ability to participate in social roles and activities | X | — | — |

| Companionship | X | — | — |

| Informational support | X | — | — |

| Emotional support | X | — | — |

| Instrumental support | X | — | — |

| Social isolation | X | — | — |

| Peer relationships | — | X | X |

| Asthma impact | — | X | X |

| Global health | X | — | — |

PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System.

PROMIS IN CLINICAL TRIALS

PROMIS instruments have been adopted for use in clinical trials. The PROMIS Fatigue short form has been adopted in multiple trials as a secondary outcome, including in a phase III Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trial (Gemcitabine Hydrochloride With or Without Erlotinib Hydrochloride Followed by the Same Chemotherapy Regimen With or Without Radiation Therapy and Capecitabine or Fluorouracil in Treating Patients With Pancreatic Cancer That Has Been Removed by Surgery), an RTOG phase II trial (Radiation Therapy With or Without Chemotherapy in Treating Patients with High-Risk Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors That Have Been Removed by Surgery), and a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) phase II trial (Pelvic Radiation Therapy or Vaginal Implant Radiation Therapy, Paclitaxel, and Carboplatin in Treating Patients with High-Risk Stage I or Stage II Endometrial Cancer). Forest Laboratories sponsored a phase IV trial utilizing PROMIS CATs in fatigue, physical function, satisfaction with participation in discretionary social activities, and sleep-related impairment in a study of milnacipran in patients with inadequate response to duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia. Whether or not a clinical trial includes a PROMIS measure, through scaling or linking instruments, an investigator can express scores from other widely used measures in the standardized T-score PROMIS metric. Ongoing discussions between the PROMIS Collaborative Group and the Critical Path Institute PRO Consortium have potential for further advancing selection and use of PRO measures in clinical trials.

NEURO-QOL

Another family of item response theory–based PRO instruments is Neuro-QOL (http://www.neuroqol.org). Utilizing methodology similar to that in PROMIS, Neuro-QOL developed CATs and short forms to assess several domains, including emotional distress, physical function, applied cognition, emotional and behavioral dyscontrol, positive affect, sleep disturbance, social functioning, social relations, stigma, pain, communication, end-of-life concerns, bowel/bladder function, and sexual function.35 Instruments are available for pediatric36 and adult use, in English and Spanish. The instruments were developed and initial validation testing was completed in stroke, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and muscular dystrophy.

CONCLUSION

PROs are a powerful tool for understanding patient health and quality of life. Like traditional clinical assessments such as blood work and other laboratory tests, PROs aid clinicians in assessing patient health and providing optimal care. Additional work is needed to increase the use and reporting of PROs in clinical trials. Likewise, the use of PROs in research and clinical practice has been hindered by variability in the quality of PRO instruments, inability to compare results across measures, and patient burden from long assessments. However, these barriers have been addressed through the creation of PROMIS, which establishes common measures, reduces response burden for the patient, and facilitates scoring by utilizing item response theory and computer technology. Quality PRO instruments are a tool for efficiently collecting valid and reliable data on a wide range of patient experiences. Most important, PROs improve our ability to understand and respond to patient symptoms, experiences, and quality of life.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009 < http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS113413>.

- 2.Willke RJ, Burke LB, Erickson P. Measuring treatment impact: a review of patient-reported outcomes and other efficacy endpoints in approved product labels. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:535–552. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sloan JA, et al. National Cancer Institute. Integrating patient-reported outcomes into cancer symptom management clinical trials supported by the National Cancer Institute-sponsored clinical trials networks. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5070–5077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohr KN. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earp JA, Ennett ST. Conceptual models for health education research and practice. Health Educ Res. 1991;6:163–171. doi: 10.1093/her/6.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Victorson DE, Anton S, Hamilton A, Yount S, Cella D. A conceptual model of the experience of dyspnea and functional limitations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Value Health. 2009;12:1018–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1263–1278. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klem M, Saghafi E, Abromitis R, Stover A, Dew MA, Pilkonis P. Building PROMIS item banks: librarians as co-investigators. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:881–888. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9498-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA PROMIS Cooperative Group. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45:S12–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stull DE, Leidy NK, Parasuraman B, Chassany O. Optimal recall periods for patient-reported outcomes: challenges and potential solutions. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:929–942. doi: 10.1185/03007990902774765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher C. Structural limits on verb mapping: the role of analogy in children’s interpretations of sentences. Cogn Psychol. 1996;31:41–81. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1996.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokkink LB, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dehaene S. Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention. Viking; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahimi K, Malhotra A, Banning AP, Jenkinson C. Outcome selection and role of patient reported outcomes in contemporary cardiovascular trials: systematic review. BMJ. 2010;341:c5707. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder CF. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer: a review of recent research and policy initiatives. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:278–300. doi: 10.3322/CA.57.5.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella D. Quality of life in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the importance of patient-reported outcomes. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:733–737. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes DE, Tager IB, Satariano WA, Yaffe K. The relationship between literacy and cognition in well-educated elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:390–395. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.4.m390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19:787–805. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caplan D, Hildebrandt N. Disorders of Syntactic Comprehension. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.FACIT.org. FACIT Measurement System. < http://www.facit.org>.

- 22.Wagner LI, et al. Development of a Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy questionnaire to assess dermatology-related quality of life in patients treated with EGFR inhibitors: The FACT-EGFRI. Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; Chicago, IL. 4–8 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esper P, Mo F, Chodak G, Sinner M, Cella D, Pienta KJ. Measuring quality of life in men with prostate cancer using the functional assessment of cancer therapy-prostate instrument. Urology. 1997;50:920–928. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cella D, Lai JS, Chang CH, Peterman A, Slavin M. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94:528–538. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillmen P, et al. The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1233–1243. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.About Soliris. Alexion Pharmaceuticals; Cheshire, CT: 1999–2011. < http://www.alxn.com/SolirisAndPNH/AboutSoliris/Default.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gershon R, Rothrock NE, Hanrahan RT, Jansky LJ, Harniss M, Riley W. The development of a clinical outcomes survey research application: Assessment Center. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:677–685. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9634-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ader DN. Developing the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S1–S2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cella D, et al. The patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothrock NE, Hays RD, Spritzer K, Yount SE, Riley W, Cella D. Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teresi JA, et al. Analysis of differential item functioning in the depression item bank from the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS): An item response theory approach. Psychol Sci Q. 2009;51:148–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR. Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:395–407. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yost KJ, Eton DT, Garcia SF, Cella D. Minimally important differences were estimated for six Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:212–232. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cella D, et al. The neurology quality of life measurement (Neuro-QOL) initiative. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.01.025. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai JS, et al. Quality of life outcomes in children with neurological conditions: Pediatric Neuro-QOL. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1545968311412054. e-pub ahead of print 25 July 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]