Abstract

Objective

Vertical rectus transposition (VRT) is used to treat abduction limitation, but new vertical deviations and anterior segment ischemia are concerns. Johnston and Crouch described superior rectus transposition (SRT), a procedure in which only the superior rectus muscle is transposed temporally. We describe our results using augmented temporal SRT with adjustable medial rectus muscle recession (MRc) for treatment of Duane syndrome I (DS) and sixth nerve palsy.

Methods

Retrospective surgical case review of patients undergoing the SRT procedure. Pre- and post-operative orthoptic measurements were recorded. Minimum follow-up was 6 weeks. Main outcome measures included angle of esotropia in primary position and the angle of head turn. Secondary outcomes included duction limitation, stereopsis, and new vertical deviations.

Results

The review identified seventeen patients (10 with DS and 7 with sixth nerve palsy). SRT+MRc improved esotropia [from 44 PD to 10.1 PD (p< 0.0001)], reduced abduction limitation [from −4.3 to −2.7 (p<0.0001)] and improved compensatory head posture [from 28°to 4° (p<0.0001)]. Stereopsis was recovered in eight patients (p=0.03). Three patients required a reoperation; one for overcorrection and 2 for undercorrection. A new primary position vertical deviation was observed in 2/7 patients with complex sixth nerve palsy and 0/10 DS patients. No patient described torsional diplopia.

Conclusions

SRT allows for the option of simultaneous medial rectus recession in patients with severe abduction imitation who require transposition surgery. SRT+MRc improved esotropia, head position, abduction limitation, and stereopsis without inducing torsional diplopia.

Introduction

Patients with Duane syndrome and sixth nerve palsy have moderate to severe limitation of abduction, often leading to primary position esotropia that is associated with a compensatory head posture, reduced stereopsis, and diplopia. Various approaches to improving eye position have been proposed, including partial and full vertical rectus muscle transposition to increase the abduction of the eye. Full vertical rectus transposition (VRT) procedures are among the most effective for treatment of the abduction deficit; however, new vertical deviations have been described in 6 to 30 % of patients 1–3. There is also the concern of anterior segment ischemia with this procedure, especially when a medial rectus muscle recession is also required.4, 5

Johnston and Crouch6 introduced a modification of the VRT in which only the superior rectus muscle is transposed. Since then, we have adopted this superior rectus transposition (SRT) technique for appropriate patients, often combining an augmented SRT with an adjustable medial rectus muscle recession (MRc).7 The purpose of this study is to present and evaluate the results of SRT+MRc to correct the esotropia and head turn in patients with Duane syndrome or sixth nerve palsy.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the Children’s Hospital Boston (CHB) Institutional Review Board. The medical records of patients treated in the Department of Ophthalmology at CHB from January 2006 to October 2010 were reviewed. Patients treated with SRT, with or without augmentation suture,8 were included. Exclusion criteria included age < 1 year, prior transposition surgery, or follow-up of less than 4 weeks. Information obtained included pre- and postoperative head turn, esotropia and hypertropia in all gaze positions, ductions, and stereopsis. Postoperative complications were also monitored, including the development of a new vertical misalignment or torsion, impairment of adduction and need for reoperation/revision procedure to improve ocular alignment (excluding postoperative adjustment of adjustable sutures). Alignment was recorded from the orthoptic evaluation. Ductions were graded on a scale from 0, indicating full ductions, through −4 for an eye that was able to move to the midline and −5 for an eye that approached but was unable to reach the midline, up to a maximum of −8 in rare cases where the eye was fixed in an extreme adducted position. Head turn measurements (measured at distance fixation) were recorded from patient records (or measured by estimation using pre- and postoperative photographs in 2 patients).

Surgical Technique

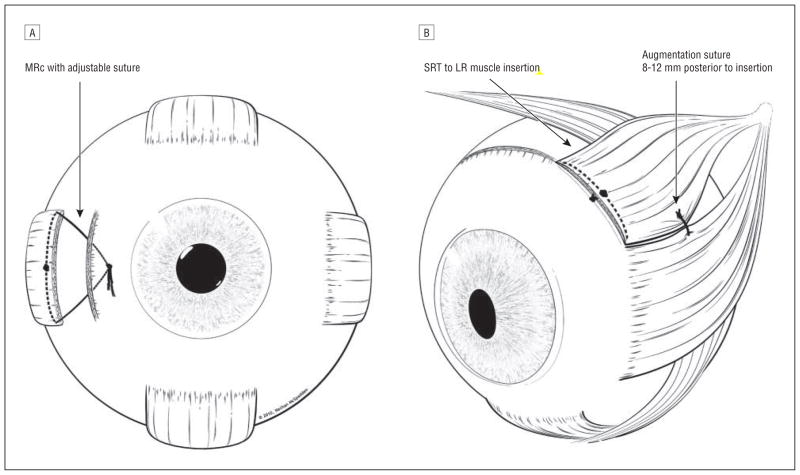

After a ‘short tag noose’ adjustable medial rectus muscle recession (described by Nihalani et al)7, 9 was performed (Figure 1A), an incision was made superotemporally and the superior rectus muscle was isolated. The muscle was then cleared of surrounding attachments, with extra care taken to separate the superior rectus muscle from the levator muscle (best achieved by removing the lid speculum and using a handheld retractor for exposure) and from the superior oblique tendon. The muscle was then secured with a double armed, 6-0 polyglactin 910 suture and detached from the globe. The posterior surface of the muscle was inspected for remaining attachments to the superior oblique tendon or frenulum. The temporal pole of the muscle was reattached at the superior pole of the lateral rectus muscle, and the nasal pole was reattached adjacent to the temporal pole of the superior rectus muscle insertion following the Spiral of Tillaux (Figure 1B). In most cases, a double armed 6-0 polyester augmentation suture was then placed by passing one needle through the lateral one quarter of the superior rectus muscle and the other needle through the superior one quarter of the lateral rectus muscle, positioning this suture 8–12 mm posterior to the insertion of the two muscles.2, 10–12 The suture was then tied to pull the two muscles together as a loop myopexy,13 with no scleral pass (except as noted below) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of the superior rectus transposition (SRT) plus medial rectus recession (MRc) procedure: A) MRc with adjustable sutures; B) SRT technique with augmentation suture. Superior oblique muscle shown partially removed for clarity; amount of muscle included in augmentation suture appeared < ¼ muscle width after tying knot.

Patients were assessed in the recovery room 1–3 hours after the procedure to check alignment and perform suture adjustment if required. The short tag noose approach allowed for a second suture adjustment to be performed (if required) within 10 days of the procedure. The postoperative follow-up visit was scheduled for 6–12 weeks after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

The paired t test was used to analyze the pre and post operative results on head turn, esotropia in primary position and limitation of abduction. Stereopsis data was compared using McNemar’s test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The record review identified 17 patients treated with the SRT over the study period, all of whom had simultaneous MRc. Patient characteristics and severity grading of all patients are summarized in Table 1. The average postoperative follow-up was 8 months (range 1.5–32 months), with 9 patients followed for 6 months or longer.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and distribution.

| Duane Syndrome | 6th Nerve Palsy | |

|---|---|---|

| N=10 | N=7 | |

| Age | 1 – 33 yr | 6 – 60 yr |

| Sex | 6M:4F | 6 F:1M |

| Follow-up | 2–32 mo | 2–16 mo |

| Abduction deficit | −3 to −5 | −4 to −5 |

| Head turn >20°* | 100% | 100% |

Patients utilized a head turn either for fusion or for fixation.

Patients with Duane syndrome were younger than the patients with sixth nerve palsy. The average abduction deficit was greater in the sixth nerve palsy group. Patients in both groups had a compensatory head turn of more than 20°.

The mean medial rectus muscle recession was 5 mm. Postoperative adjustment was performed in 7/17 patients. The final amount of recession ranged from 0 to 8 mm after adjustment, but only one patient had a recession of >6 mm. In six cases, there were minor variations from the surgical technique noted in Methods. One patient, the first in the series, did not have an augmentation suture placed. In 3 patients the polyester augmentation suture was secured to the sclera; one of these patients also underwent a simultaneous 9 mm recession of the lateral rectus muscle to correct globe retraction. Three patients, all with a primary position ET of ≥50 PD, had a simultaneous or subsequent recession of the contralateral medial rectus muscle.

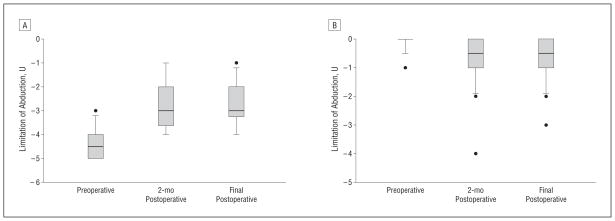

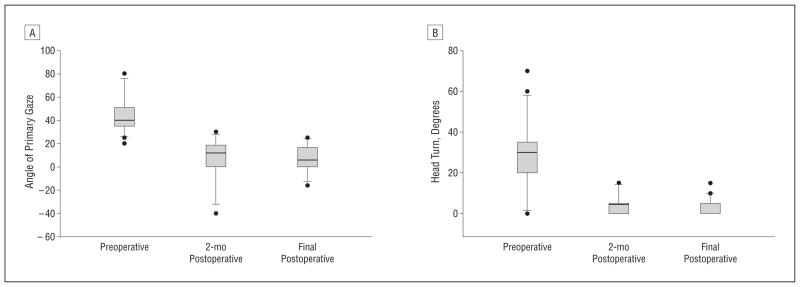

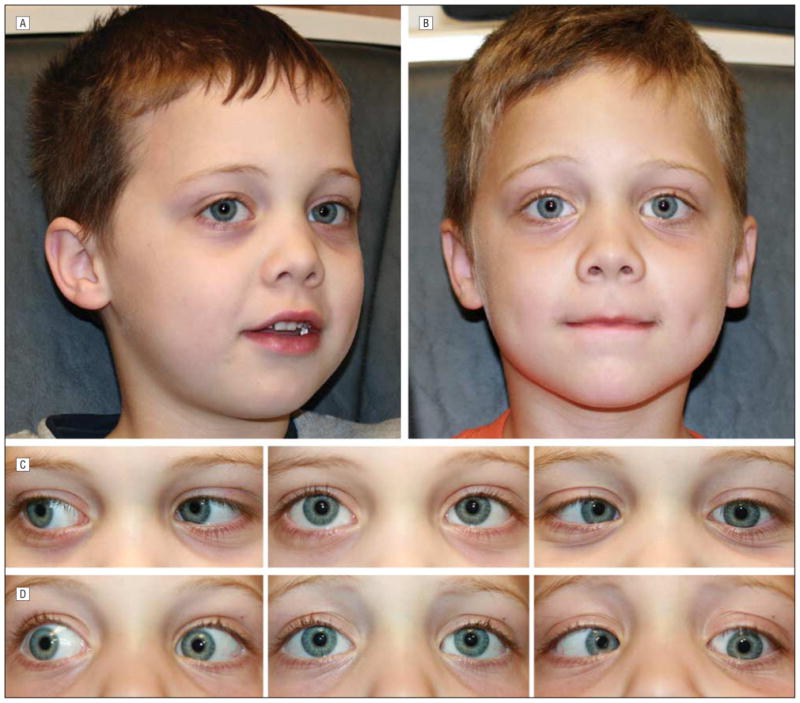

Mean esotropia in primary position improved from 44 ± 16 PD preoperatively to 10 ± 9 PD postoperatively (Figure 2A; p< 0.0001). Five patients became orthophoric at distance in primary position without spectacle correction. There was also a mean 21° improvement in head turn (Figure 2B, p < 0.0001) and a 1.6 unit improvement in abduction (Figure 3A, p < 0.0001), with a 0.6 unit reduction in adduction (Figure 3B, p = 0.009). The improvement in head turn and abduction is documented in a representative pediatric patient (Figure 4). Stereopsis in primary position was measurable in 5/17 patients (29 %) before surgery and improved to 13/17 patients (76%) after surgery (Table 2, p = 0.03).

Figure 2.

Surgical results A) Alignment in primary position (n=17). Positive values represent esotropia. B) Head turn before and after surgery (n=16). Head turn was not assessed in one patient who did not demonstrate fusion. Final postoperative visit represents a mean follow-up of 8 months (range, 1.5 to 32 months). [Box and whisker diagram: The bottom and top of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentile (the lower and upper quartiles, respectively); the band near the middle of the box is the 50th percentile (the median). The ends of the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum of all the data. Any data not included within the whisker is plotted as an outlier with a dot.]

Figure 3.

Ductions before and after surgery (n=17) A) Abduction limitation; B) Adduction limitation. Final postoperative visit represents a mean follow-up of 8 months (range, 1.5 to 32 months). To prevent the measurements of one overcorrected patient from confounding postoperative averages, we re-analyzed the values after excluding that patient and found no substantive change in the calculated means or p values.[Box and whisker diagram: The bottom and top of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentile (the lower and upper quartiles, respectively); the band near the middle of the box is the 50th percentile (the median). The ends of the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum of all the data. Any data not included within the whisker is plotted as an outlier with a dot.]

Figure 4.

Head position and motility in a five and a half year old boy preoperatively (A, C) and two months after augmented SRT and a 4.5mm left medial rectus muscle recession (B, D)

Table 2.

Distribution of gain in stereopsis.

| Stereopsis | Duane Syndrome | 6th Nerve Palsy |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 4/9 (44%) | 1/6 (16 %) |

| Postoperative | 8/9 (88%) | 5/6 (83%) |

Improvement was statistically significant (p=0.03). Data not included for 1 patient with Duane Syndrome (not recorded) and 1 patient with 6th nerve palsy (blind in one eye)

New onset vertical deviations in primary position (mean 10 ± 2.8 PD) were observed in 2 patients (11%). Both patients had a chronic sixth nerve palsy; one of these patients is described below, while the other patient had multiple orbital fractures in addition to a sixth nerve palsy. No patient with Duane syndrome had an induced vertical deviation. There was no new onset, symptomatic hypotropia in gaze towards the affected side. In several cases a hypotropia was already present in the affected eye before surgery due to aberrant innervation (e.g. Figure 4) or multiple cranial nerve palsies.

Torsion was assessed postoperatively in 6 patients (by double Maddox rod test (3 patients) or anatomic torsion (3 patients)). Of these, 2 patients did not have torsion and 3 had incyclotorsion (mean 4°; values, 2°, 2°, and 5°). None of these patients were symptomatic. In another case, the augmentation suture (placed through sclera) was removed in the post-anesthesia care unit to reverse incyclotorsion and diplopia that was noted in the immediate postoperative period; however, at the final postoperative visit, that patient had 2–3° excyclotorsion.

A second procedure was required in 3 cases. Two patients had undercorrections; one was a 4 year-old boy with a residual esotropia of 20 PD who responded to full hyperopic correction and a 7.5 mm recession of the contralateral medial rectus muscle. The second was a 16-year-old boy with a 6th nerve palsy secondary to pilocytic astrocytoma (post-irradiation) who developed a recurrence (with a 14 PD hypotropia) over the first 2 months after surgery. He was subsequently treated with an augmented inferior rectus transposition, which partially reduced the head turn and improved the esotropia from 25 PD to 10 PD, but with a persistent hypotropia. The overcorrection occurred in a 1-year-old girl with Duane syndrome who developed a consecutive exotropia and adduction limitation after surgery; this patient was treated with reversal of the transposition, recession of the lateral rectus muscle, and advancement of the medial rectus muscle so that the final net procedure was simply a 2 mm medial rectus recession and lateral rectus recession.

Discussion

Over the past century, a variety of partial and full transposition procedures of the vertical rectus muscles have been proposed in an effort to improve eye alignment in patients with abduction limitation.2, 8, 14–19 In 2004, Rosenbaum reviewed the results of vertical rectus transposition (VRT) with posterior fixation, orbital fixation, and partial vertical rectus transposition in patients with sixth nerve palsy and Duane syndrome.15 His study showed a marked improvement in the range of binocular single vision of patients who had undergone a VRT with posterior fixation. Guyton has described a vessel-sparing, “crossed adjustable” VRT that allows for adjustment of both the superior and inferior rectus muscles; this technique does not allow for an augmentation suture. 20

New vertical strabismus is a concern with VRT; in one report,1 6–30% of patients treated with VRT had a clinically-significant new vertical strabismus. VRT also carries with it a theoretical increase in the risk of anterior segment ischemia, especially if recession of the medial rectus muscle is required.4, 5 Johnston and Crouch6 were the first to propose that it might be possible to gain the benefits of transposition surgery by transposing only the superior rectus muscle (with or without medial rectus muscle recession), thus reducing the amount of surgery required as well as the theoretical risk of anterior segment ischemia. We adopted this technique, modifying it with the addition of a short tag noose adjustable suture7 on the medial rectus muscle to allow for optional suture adjustment up to 10–14 days after surgery, along with routine use of an augmentation suture.

Many patients with abduction limitation will develop tightness or contracture of the medial rectus muscle over time. This can limit the effectiveness of a transposition procedure.15 Because we transposed only the superior rectus muscle in our procedure, we were comfortable routinely recessing the medial rectus muscle to reduce any potential abduction limitation. By making this recession adjustable, we were able to fine-tune the horizontal alignment in the postoperative period, an added benefit considering that a transposition procedure might have a less predictable result on horizontal alignment than a recession or resection. The addition of an abducting force to the eye has a theoretical advantage of preventing recurrence of esotropia over time, but the duration of follow-up in the present study is not sufficient to address this question. Since only one muscle is transposed, even patients who have had a prior recess/resect procedure may be considered candidates for the SRT (or SRT+MRc) procedure.

The results of the SRT+MRc in our hands appear to be comparable to the results of the VRT (Tables 3 and 4).10, 11, 21–24 It is notable, however, that in one undercorrected patient (with a sixth nerve palsy secondary to pilocytic astrocytoma), the subsequent transposition of the inferior rectus muscle improved the ocular alignment. In our experience, both SRT+MRc and VRT are superior to recession of the ipsilateral medial rectus muscle for patients with severe abduction limitations, as the amount of medial rectus muscle recession required tends to cause a new adduction limitation and contributes no chronic abducting force to prevent recurrence.

Table 3.

Comparison of results of VRT (reported in literature) and SRT (present study) for treatment of esotropia in Duane syndrome.

| Duane Syndrome | VRT (n=64) Rosenbaum et al15 | VRT (n=38) Yazdian et al10 | SRT+MRc (n=10) Present study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre op | Post op | Pre op | Post op | Pre op | Post op | |

| Head turn (mean degrees) | 20 | 5 | 38 | 12 | 24 | 3 |

| Esotropia (mean PD) | 19 | 6 | 32 | 9 | 37 | 10 |

| Abduction (mean change) | −3.8 | −2.7 (29%) | −4 | −2 | −4 | −2 (50%) |

| Average postoperative follow-up (months) | 11 | 18 | 8 | |||

| Induced vertical deviation | 5/64 | 3/38 | 0/10 | |||

VRT, vertical rectus muscle transposition; SRT, superior rectus muscle transposition; MRc, medial rectus muscle recession.

Table 4.

Comparison of results of VRT (reported in literature) and SRT (present study) for treatment of esotropia in 6th nerve palsy.

| 6th nerve Palsy | VRT (n=24) Yazdian et al10 | SRT+MRc (n=7) Present study | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre op | Post op | Pre op | Post op | |

| Head turn (mean degrees) | 24 | 7 | 36 | 5 |

| Esotropia (mean PD) | 44.7 | 12.5 | 53.5 | 16.8 |

| Abduction (mean change) | −4.2 | −2.3 | −4.8 | −3 |

| Average postoperative follow-up (months) | 18 | 10 | ||

| Induced vertical deviation | 0/24 | 2/7 | ||

| Reoperation | 6/24 | 1/7 | ||

VRT, vertical rectus muscle transposition; SRT, superior rectus muscle transposition; MRc, medial rectus muscle recession.

One patient was overcorrected, but we do not believe it was a result of the transposition, because after fully reversing the transposition, the overcorrection persisted until the previously-recessed medial rectus muscle was advanced (and the lateral rectus muscle recessed). None of the patients with Duane syndrome developed a hypotropia after surgery, but two patients with sixth nerve palsy did; we believe these were anomalous cases because one had suffered orbital fractures requiring surgery and the other had the augmentation suture attached to sclera. Torsional diplopia was not a problem, except in one unusual case where the patient (treated with scleral fixation of the augmentation suture) described such distressing torsional diplopia in the recovery room that the suture was removed before discharge, yet that patient ended up with excyclotorsion after surgery. While it is not possible to make general recommendations about the augmentation suture based on the latter two cases, we advise that surgeons adopting the SRT procedure use a simple loop myopexy of superior rectus muscle to lateral rectus muscle for augmentation until more experience is gained and published.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature and the follow-up of less than 6 months in 50 % of patients. There was no control group treated with medial rectus recession alone. Some patients were too young to adequately assess stereopsis at presentation, so it is possible that some of the observed improvement in stereopsis may have been due to patient maturation. Many patients were also too young to objectively assess torsion. Field of binocular vision was not tested in this retrospective study; however, the 1.6 unit improvement in abduction combined with a 0.6 limitation of adduction is consistent with an increase in the range of motion of the eye.

The study addresses only temporal SRT – it does not address the question of nasal SRT.25 We performed nasal SRT in one patient, but had to reverse the procedure 3 days later due to intolerable torsional diplopia (unpublished case).

How it is possible that a vertical deviation and torsional diplopia did not result from an unbalanced transposition of the superior rectus muscle is a matter of speculation. We believe that because the transposition also involves a slight advancement of the superior rectus muscle (to follow the Spiral of Tillaux), this increases the effective strength of the superior rectus muscle to counterbalance the weakening of the vertical effect that results from the transposition. However such an alteration of the superior rectus muscle insertion, extending the temporal edge to the lateral rectus tendon insertion and then following the muscle to the point of the augmentation suture, should increase torsion that much further. Enhanced modeling of the forces operating within the orbit may be required to begin to explain this apparent inconsistency. The clinically-insignificant hypotropia noted in abduction in several cases after surgery appeared to be a consequence of aberrant innervation, as it was present prior to surgery in all patients.

In conclusion, in patients treated with SRT+MRc, there was a markedly reduced esotropia in primary position, increased abduction, and improved head position with minimal effect on adduction and few cases of vertical or torsional diplopia. Considering these results, we recommend SRT+MRc for patients with profound abduction limitation in which there is no reasonable chance that a horizontal rectus muscle procedure alone will be satisfactory. The procedure is especially helpful in cases where there may be simultaneous contracture of the medial rectus muscle, as it allows a medial rectus muscle recession to be combined with a transposition procedure without greatly increasing the risk of anterior segment ischemia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Mackinnon, Lead Orthoptist, Department of Ophthalmology, for assistance with orthoptic measurements and interpretation of head turn photographs, Ethan Bickford for formatting the clinical images, and Peter Forbes, Senior Biostatistician, Children’s Hospital Boston, for help with statistical analysis. This work was supported in part by the Children’s Hospital Ophthalmology Foundation. The statistical work was conducted with partial support from Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Award #UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, the National Center for Research Resources, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presented at the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Meeting, San Diego, California, April 2011

References

- 1.Ruth AL, Velez FG, Rosenbaum AL. Management of vertical deviations after vertical rectus transposition surgery. J AAPOS. 2009;13(1):16–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velez FG, Foster RS, Rosenbaum AL. Vertical rectus muscle augmented transposition in Duane syndrome. J AAPOS. 2001;5(2):105–13. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2001.112677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbaum AL. Adjustable vertical rectus muscle transposition surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(10):1346. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080100026015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murdock TJ, Kushner BJ. Anterior segment ischemia after surgery on 2 vertical rectus muscles augmented with lateral fixation sutures. J AAPOS. 2001;5(5):323–4. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2001.118668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders RA, Phillips MS. Anterior segment ischemia after three rectus muscle surgery. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(4):533–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston SC, Courch ERC, Jr, Crouch ER. An innovative approach to transposition surgery is effective in treatment of Duane’s syndrome with esotropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:E-Abstract 2475. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nihalani BR, Whitman MC, Salgado CM, et al. Short tag noose technique for optional and late suture adjustment in strabismus surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(12):1584–90. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster RS. Vertical muscle transposition augmented with lateral fixation. J AAPOS. 1997;1(1):20–30. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(97)90019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter DG, Dingman RS, Nihalani BR. Adjustable sutures in strabismus surgery. In: Wilson ME, editor. Pediatric Ophthalmology: Current Thought and a Practical Guide. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yazdian Z, Rajabi MT, Ali Yazdian M, et al. Vertical rectus muscle transposition for correcting abduction deficiency in Duane’s syndrome type 1 and sixth nerve palsy. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2010;47(2):96–100. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20100308-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yazdian Z, Rajabi MT, Yazdian MA, et al. Vertical Rectus Muscle Transposition for Correcting Abduction Deficiency in Duane’s Syndrome Type 1 and Sixth Nerve Palsy. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2009:1–5. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20100308-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Struck MC. Augmented vertical rectus transposition surgery with single posterior fixation suture: modification of Foster technique. J AAPOS. 2009;13(4):343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong I, Leo SW, Khoo BK. Loop myopexy for treatment of myopic strabismus fixus. J AAPOS. 2005;9(6):589–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velez FG, Thacker N, Britt MT, et al. Rectus muscle orbital wall fixation: a reversible profound weakening procedure. J AAPOS. 2004;8(5):473–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenbaum AL. Costenbader Lecture. The efficacy of rectus muscle transposition surgery in esotropic Duane syndrome and VI nerve palsy. J AAPOS. 2004;8(5):409–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishida Y, Inatomi A, Aoki Y, et al. A muscle transposition procedure for abducens palsy, in which the halves of the vertical rectus muscle bellies are sutured onto the sclera. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2003;47(3):281–6. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(03)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Britt MT, Velez FG, Thacker N, et al. Partial rectus muscle-augmented transpositions in abduction deficiency. J AAPOS. 2003;7(5):325–32. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(03)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simons BD, Siatkowski RM, Neff AG. Posterior fixation suture augmentation of full-tendon vertical rectus muscle transposition for abducens palsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2000;20(2):119–22. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200020020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das JC, Chaudhuri Z, Bhomaj S, Sharma P. Lateral rectus split in the management of Duane’s Retraction Syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2000;31(6):499–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phamonvaechavan P, Anwar D, Guyton DL. Adjustable suture technique for enhanced transposition surgery for extraocular muscles. J AAPOS. 14(5):399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds JD, Coats DK. Transposition procedures for sixth nerve palsy. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2009;46(6):324–6. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20091104-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neugebauer A, Fricke J, Kirsch A, Russmann W. Modified transposition procedure of the vertical recti in sixth nerve palsy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131(3):359–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00805-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bansal S, Khan J, Marsh IB. Unaugmented vertical muscle transposition surgery for chronic sixth nerve paralysis. Strabismus. 2006;14(4):177–81. doi: 10.1080/09273970601026201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Britt MT, Velez FG, Velez G, Rosenbaum AL. Vertical rectus muscle transposition for bilateral Duane syndrome. J AAPOS. 2005;9(5):416–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider JL, Crouch ER, Jr, Crouch ER., III An innovative approach to transposition surgery is effective in treatment of type III Duane’s syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010:51, E-Abstract 3012. [Google Scholar]