Abstract

Translational isoforms of the glucocorticoid receptor α (GR-A, -B, -C1, -C2, -C3, -D1, -D2, and -D3) have distinct tissue distribution patterns and unique gene targets. The GR-C3 isoform-expressing cells are more sensitive to glucocorticoid killing than cells expressing other GRα isoforms and the GR-D isoform–expressing cells are resistant to glucocorticoid killing. Whereas a lack of activation function 1 (AF1) may underlie the reduced activity of the GR-D isoforms, it is not clear how the GR-C3 isoform has heightened activity. Mutation analyses and N-terminal tagging demonstrated that steric hindrance is probably the mechanism for the GR-A, -B, -C1, and -C2 isoforms to have lower activity than the GR-C3 isoform. In addition, truncation scanning analyses revealed that residues 98 to 115 are critical in the hyperactivity of the human GR-C3 isoform. Chimera constructs linking this critical fragment with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain showed that GR residues 98 to 115 do not contain any independent transactivation activity. Mutations at residues Asp101 or Gln106 and Gln107 all reduced the activity of the GR-C3 isoform. In addition, functional studies indicated that Asp101 is crucial for the GR-C3 isoform to recruit coregulators and to mediate glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Thus, charged and polar residues are essential components of an N-terminal motif that enhances the activity of AF1 and the GR-C3 isoform. These studies, together with the observations that GR isoforms have cell-specific expression patterns, provide a molecular basis for the tissue-specific functions of GR translational isoforms.

Glucocorticoids are used to treat numerous inflammatory conditions such as asthma, arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and transplant rejection and various autoimmune disorders as well as certain cancers such as Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and multiple myeloma (1). However, it is not clear why glucocorticoid responses among tissues and individuals can be drastically different. Lymphocytes and osteoblasts are sensitive to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, whereas hepatocytes and lung epithelial cells require glucocorticoids for survival (2). We found that glucocorticoid receptor (GR) translational isoforms may mediate distinct glucocorticoid responses. GR isoforms include GRα and GRβ generated by alternative splicing, with GRα being expressed at relatively higher levels in most tissues examined (3, 4). We have reported that each GR transcript generates additional isoforms via alternative translation initiation mechanisms (5), and, in this article, we use GR to refer GRα. Alternative translation start sites at residues 1, 27, 86, 90, 98, 316, 330, and 336 of the human GR mRNA are responsible for the GR-A, -B, -C1, -C2, -C3, -D1, -D2, and -D3 isoforms, respectively. These GR isoforms have distinct tissue distribution patterns (5). The pancreas and colon have the highest amounts of the GR-C isoforms, whereas spleen and lung have the highest amounts of the GR-D isoforms. Immature dendritic cells have predominantly the GR-D isoforms, whereas mature dendritic cells have predominantly the GR-A isoform (6). T cells upon activation by mitogen selectively increased GR-C isoforms (7). When individual GR isoforms are expressed at comparable levels in U-2 OS or Jurkat cells, they regulate unique sets of genes and mediate glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in distinct fashions (7, 8). The GR-C3 isoform has enhanced activity as demonstrated by the earlier onset and higher percentage of cell death in the GR-C3 isoform–expressing cells compared with those in the cells expressing other GR isoforms. Dexamethasone (DEX) treatment induced apoptosis in 50% of cells expressing the GR-C3 isoform, in 30% of cells expressing the GR-A or -B isoforms, and in less than 10% (background level) of the GR-D3-expressing cells. The heightened activity of the GR-C3 isoform was also observed in GRE-driven reporter assay systems (5), although the mechanisms underlying the unique transactivation activity of the GR isoforms are not known.

GR binding to glucocorticoids induces conformational changes, dissociation from chaperone proteins, dimerization of the receptor, nuclear import, and DNA and/or protein binding that are followed by transcriptional regulation (9). Several functional domains in GR have been described in detail in a series of seminal studies (10–13). the DNA binding domain (DBD) is centrally located in the primary sequence of the GR and is most highly conserved among nuclear receptors (14). The ligand binding domain (LBD) toward the C terminus encompasses the glucocorticoid binding site, the receptor dimerization interface, and a transcriptional activation function (τ-2 or AF2) (15). A series of studies found that the LBD is critical in recruiting the coactivators that initiate chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activation (16, 17). Hydrophobic residues in AF2 and other LBD helices form a docking groove for the hydrophobic leucine residues in the LXXLL motifs in coactivators (15). Additional hydrogen bonds between charged residues (eg, Glu755, Lys579, Asp590, and Arg585 on GRs) and the LXXLL motif further strengthen the interface between GRs and coactivators (15). In contrast to the case of the DBD and LBD, the structure of the N terminus of the GR is unresolved. The GR N terminus shares the least identity with other nuclear receptors. The major transactivation domain (τ-1 or AF1) is located within residues 77 to 262 (11). Recently, a core region of τ-1 has been localized to residues 187 to 244, a segment potentially rich in α-helices (18, 19). Hydrophobic residues within this core region underlie the activity of τ-1 (20–22). These residues interact directly with coregulators such as Ada2 (20) and cAMP binding protein–binding protein (CBP) (21) and transcription factors such as TATA box binding protein (23). The lack of τ-1 is probably the mechanism underlying the reduced transactivation activity of the GR-D isoforms. However, all other GR isoforms contain the core region of τ-1, and the distinct transactivation activities among GR-A, -B-, -C1, -C2, and -C3 are not understood.

Using multiple molecular approaches, we determined the mechanisms underlying the hyperactivity of the GR-C3 isoform. Mutation analyses and N-terminal tagging demonstrated that steric hindrance is probably the mechanism for the GR-A, -B, -C1, and -C2 isoforms to have lower activity than the GR-C3 isoform. Truncation scanning and site-directed mutagenesis delineated the residues critical for the activity of the GR-C3 isoform in reporter assays, in CBP recruitment, and in inducing apoptosis. These studies improve our understanding of the role of GR isoforms in the tissue-selective glucocorticoid responses and may provide a basis for the development of new anti-inflammatory and antineoplastic regimens.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Dexamethasone (1,4-pregnadien-9α-fluoro-16α-methyl-11β,17,21-triol-3,20-dione) was purchased from Steraloids. Rabbit anti-GR antibodies were from Thermo Fisher. Rabbit anti-CBP, anti-p300, and anti-BRG1 antibodies were from Millipore. Rabbit anti-GRIP1 antibodies were from Bethyl Laboratories. Mouse anti-GAL4 DBD was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Goat antirabbit or antimouse antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was from Jackson ImmunoResearch. All other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified.

Cell culture

COS-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 5% US defined fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone Laboratories), 2 mM glutamine, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. U-2 OS cells were maintained in DMEM-F12 (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS and glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin as above. U-2 OS cell lines stably expressing the GR-C3 isoform were previously described (5). U-2 OS cell lines stably expressing the GR-C3 Asp101Lys mutants were generated according to the published protocol (5). For selection and maintenance of positive clones, 500 and 200 μg/mL of hygromycin, respectively, were used. Receptor levels in the stable clones were compared using Western blot analysis.

To transfect COS-1 or U-2 OS cells at approximately 80% confluence, Transit LT1 reagent (Mirus Corp) was used at 3 to 5 μL/1 μg of DNA, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Drug or vehicle treatment started 24 hours after transfection and lasted for 1 to 24 hours in growth medium supplemented with 5% charcoal-dextran–stripped FBS.

DNA constructs and site-directed mutagenesis

Plasmids pTRE-GR, pMMTV-luc, and pGL3-hRL were described previously (5, 8). pBind and pG5luc were obtained from Promega. GAL4 DBD was cloned into pBind between EcoRV and NotI. The original GAL4 DBD was removed by using NheI and EcoRV. GR and/or estrogen receptor (ER) fragments were then cloned into 5′ of GAL4 DBD between NheI and EcoRV. The yellow fluorescence protein (YFP)–tagged GR-C3 isoform was described previously (5) and the FLAG (Asp-Tyr-Lys-Asp-His-Asp)–tagged and HA (Tyr-Pro-Tyr-Asp-Val-Pro-Asp-Tyr)–tagged GR-C3 isoforms were constructed by inserting the tag sequence into the N terminus of the GR in the pTRE plasmid. pcDNA-FLAG-CBP (plasmid 32908; Addgene) was described previously (24). Mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using QuikChange (Stratagene). All cloning and mutagenesis products were verified by DNA sequencing at the Genomics Core at Northwestern University.

Western blot analysis

Procedures for preparing cell lysates for Western blot analysis were described previously (5). Lysates containing 10 to 50 μg of proteins were resolved on 4% to 12% NuPage Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen), and titers for antibodies were as follows: anti-GR antibodies, 1:500; anti-GAL4 DBD, 1:8,000; anti-FLAG, 1:2000; antitubulin, 1:25,000; and anti-β-actin, 1:100,000. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antirabbit or antimouse antibodies were used at a 1:10,000 dilution for 30 minutes. After 3 washes, the membrane was probed with Amersham ECL Plus reagent (GE Healthcare) and exposed to Amersham ECL films (GE Healthcare).

Luciferase reporter assays

Five to 50 ng of pTRE-GR, 200 ng of pMMTV-Luc reporters, and 30 ng of pGL3-hRL were transfected into COS-1 cells on 12-well plates. In separate experiments, 500 ng of pBind-GR and equal amounts of pG5luc were transfected into COS-1 cells on 12-well plates. pBind plasmids express GR, ER, and GAL4-DBD chimeras and Renilla luciferase. pG5luc responds to GAL4 and expresses firefly luciferase. Luciferase activity was measured as described previously (5). In each experiment, the firefly luciferase activity normalized with the Renilla luciferase activity was measured in triplicate, averaged, and further normalized by protein levels. Each experiment was repeated 3 to 4 times. At 24 hours after transfection or treatment, cells were lysed and harvested. Then 10 μL of lysates was assayed for luciferase activity using Promega reagent on a luminometer (BioTek Instruments).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were performed using ChIP kits from Millipore according to the manufacturer's protocol. In brief, 5 × 106 cells grown on 150-mm dishes supplemented with charcoal-stripped FBS for 3 days were treated with vehicle or DEX (100 nM) for 6 hours. Cells were then harvested in lysis buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors and sonicated on a Branson sonifier 150 (Branson Ultrasonics) at setting 4 with 10-second pulses for 4 times on ice. The amount of total input DNA for each immunoprecipitation reaction was 35 μg. The amounts of antibodies per immunoprecipitation reaction were 4 μL for anti-GR, 2 μL for anti-CBP, 5 μL for anti-p300, 10 μL for anti-GRIP1, and 5 μL for BRG1. The level of precipitated DNA containing a 146-bp granzyme A promoter region (8) was quantified using real-time PCR analysis on a Prism 7500 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). Each reaction (20-μL total volume) contains 10 μL of the 2× Universal PCR Master Mix, No AmpErase (Applied Biosystems) and 4 pmol of the primers and probes. Each experiment was performed in duplicate at least twice. Quantification was achieved using the Sequence Detection Software 2.0 Absolute Level subroutine (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences were 5′-GCACTGTGCCCTATTCAAGAAACC and 5′-ACACAAGGCAAACCATACATGCAG and the probe (FAM-labeled) sequence was 5′-ATCCAAGAACATCTGGTGCAGGAGGT. All measurements were normalized to the level of input DNA.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed using U-2 OS cells stably expressing GR-C3 or GR-C3 Asp101Lys. Cells were grown to 60% confluence on 100-mm dishes and transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA-FLAG-CBP. At 48 hours after transfection, cells were treated with vehicle or DEX (100 nM) for 1 hour. Cells were then harvested in lysis buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 gel, according to the manufacturer's protocol. During lysing, incubation, and washing, 100 nM DEX was added to appropriate samples. Elution was performed using loading buffer, and Western blotting was performed, as described above.

Real-time RT-PCR

Cells grown in medium supplemented with charcoal-stripped FBS were treated with vehicle or DEX (100 nM) for 6 hours. RNA samples were extracted from cells using an Absolutely RNA RT-PCR Miniprep Kit (Stratagene) and treated with DNase according to the manufacturer's protocol. The level of individual mRNA in each sample was measured using the 1-step RT-PCR procedure on a Prism 7500HT thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). Each reaction (25-μL total volume) contains 12.5 μL of the 2× Universal PCR Master Mix, No AmpErase, 1.25 μL of the predeveloped gene expression system (Applied Biosystems), 250 ng of total RNA, 2 U/μL of RNase inhibitor (Roche Applied Science) and 0.4 U/μL MuLV reverse transcriptase (Roche Applied Science). Each experiment was performed in duplicate at least twice. Quantification was achieved using the Sequence Detection Software 2.0 Absolute Level subroutine. Human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase levels were measured as described above using primers 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC and 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTT and probe 5′-CAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAGCC labeled with the FAM reporter at the 5′ end and TAMARA quencher at the 3′ end. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase levels were used to normalize the levels of granzyme A.

Flow cytometry analysis

Annexin V and propidium iodide labeling was processed using the annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate apoptosis detection kit (Biovision, Mountain View, California), according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 1.5 × 105 control or treated cells were processed and 1 × 104 cells were analyzed using an LSR II flow cytometer (BD) with an excitation of 488 nm and emission at 530 (for annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate) or 585 nm (for propidium iodide).

Statistical analysis

Averages ± SEM are presented. One-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey post hoc comparison using Prism software (GraphPad Software) to compare the differences among three or more samples. To compare two samples, Student's t tests were performed. A P value < .05 was considered significant.

Results

The GR-C3 isoform has heightened transactivation activity

The human GR-C3 isoform and the isoforms produced from upstream start codons (GR-A, -B, -C1, and -C2 isoforms) all contain the τ-1 core region, whereas the upstream isoforms have longer N termini than the GR-C3 isoform, ranging from a 97-amino acid extension in the GR-A isoform to 8 additional residues in the GR-C2 isoform. Figure 1A illustrates the locations of the start codons responsible for the expression of each of the isoform. We previously reported in both transiently transfected cells and stable cell lines that the GR-C3 isoform induces GRE-driven luciferase activity twice as effectively as the GR-A, -B, -C1, or -C2 isoforms and 5 times as high as the GR-D isoforms (5). In addition, endogenous genes, granzyme A and caspase 6, for instance, are regulated by GR isoforms in a manner reflective of the observations made with the GRE-driven reporters (8). We confirmed that the GR-C3 isoform has the highest activity in inducing the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-driven luciferase reporter gene expression (Figure 1B). Renilla luciferase activity driven by a null promoter was used to monitor transfection efficiency. Firefly luciferase induction normalized by Renilla luciferase activity was compared among receptor isoforms. The GR-C3 isoform induced the MMTV reporter expression twice as effectively as the GR-A, -B, -C1, or -C2 isoforms and 5 times as effectively as the GR-D isoforms. The expression level of each GR isoform was comparable (Figure 1B). The MMTV promoter is relatively more complex than the simple GRE used previously. The GR-C3 isoform had higher activity than the other GR isoforms over a wide range of receptor levels, whereas previous experiments demonstrated a similar phenomenon in a DEX dose-dependent fashion (5).

Figure 1.

The human GR-C3 (hGR-C3) isoform has heightened transactivation activity. A, Diagram of the human GRα isoforms. Numbers on the left indicate the locations of the start codons responsible for the expression of the corresponding GR isoforms. For example, GRα-A contains amino acids 1 through 777. τ-1c, transactivation function 1 core (187–244). B, Transactivation activity of GR isoforms. Increasing amounts of GR isoform-expressing pTRE constructs (5–50 ng) were cotransfected with 200 ng of pMMTV-Luc reporter genes and 100 ng of pGL3-hRL into COS-1 cells on 12-well plates in glucocorticoid-free media (100,000 cells/well in triplicate). At 24 hours after transfection, cells were treated with vehicle or DEX (10 nM). After another 24 hours, cells were harvested and lysed. Renilla (transfection control) and firefly luciferase activities were determined on a BioTek luminometer. Relative light units (RLU) indicate the activity of firefly luciferase normalized by Renilla luciferase activity. Shown is a representative of at least 4 experiments. Expression levels of GR isoforms in each well are similar as indicated by a representative Western blot analysis. *, Significantly greater than GRα; +, significantly less than GRα; P < .05, ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests.

Steric hindrance in GR N terminus

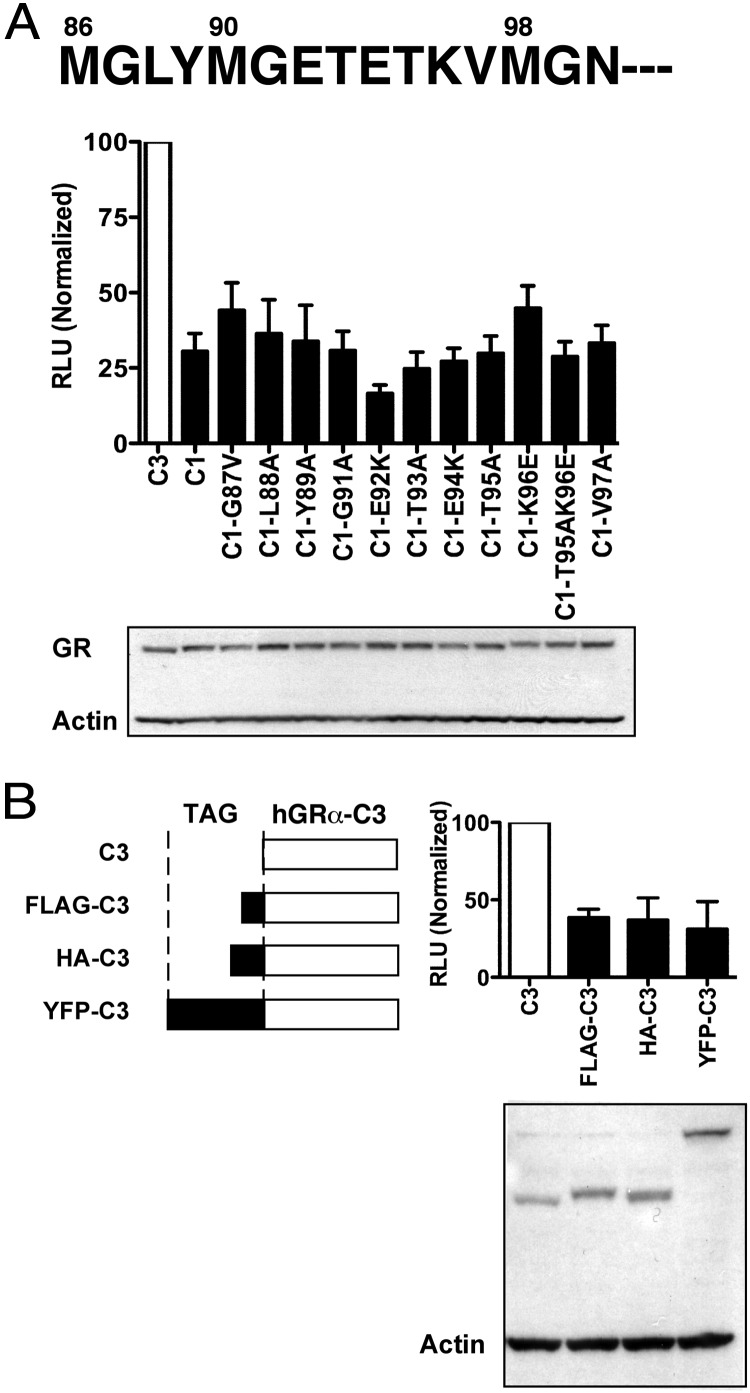

There are 2 potential mechanisms for the heightened activity of the GR-C3 isoform. First, there may exist an inhibitory domain upstream of the start codon for the GR-C3 isoform. This inhibitory domain should be downstream of residue 90, the start codon for the GR-C2 isoform because the GR-C2 isoform, similar to the other upstream isoforms, has significantly less activity than the GR-C3 isoform (Figure 1B). To test the hypothesis that there exists an inhibitory domain upstream of Met98, we performed site-directed mutagenesis. We used the GR-C1 isoform as a representative of the upstream GR isoforms and replaced individual or combinations of residues in the potential inhibitory segment (Figure 2A). To disrupt potential intra- and intermolecular interactions, charged residues were replaced with residues carrying reversed charges. Likewise, residues with branched side chains were replaced with alanines, and glycine was replaced with alanine or valine. None of the mutations increased the activity of the GR-C1 isoform to that of the GR-C3 isoform, suggesting that there is unlikely an inhibitory domain upstream of Met98. The second possibility for the heightened activity of the GR-C3 isoform is that fragments upstream of residue 98 physically block the recruitment of cofactors that are necessary for enhanced transactivation activity. To test the hypothesis that steric hindrance is the mechanism for the GR-A, -B, -C1, and -C2 isoforms to have lower activity than the GR-C3 isoform, we placed a series of unrelated sequences upstream of Met98 (Figure 2B). FLAG, HA, or YFP all inhibited the activity of the GR-C3 isoforms. These results support the hypothesis that steric hindrance independent of the identity of the residues upstream of Met98 probably masks the activity of the GR-C3 isoform. We determined the role of specific residues and segments of the N terminus in recruiting CBP below.

Figure 2.

Steric hindrance rather than an inhibitory motif in the N terminus underlies the differential transactivation activities of GR isoforms. A, Comparison of transactivation activity of the GR-C3 isoform and the GR-C1 isoform harboring various mutations. The GR-C1 isoform was used as a representative of GR-A, -B, and -C2 isoforms, and they all have less than half of the activity of the GR-C3 isoform. Individual or double mutations of residues upstream of Met98 were as indicated. Twenty nanograms of plasmid DNA was transfected into COS-1 cells. B, Addition of unrelated domains upstream of the GR-C3 start codon suppresses transactivation activity. FLAG, Asp-Tyr-Lys-Asp-His-Asp; HA, Tyr-Pro-Tyr-Asp-Val-Pro-Asp-Tyr; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein. Representative Western blots of the protein levels are shown. Luciferase activities (percentage, normalized to protein levels) of the constructs represented by the solid bars are significantly less than those of the GR-C3 isoform; P < .05, ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests. RLU, relative light unit.

Residues 98 to 115 are critical for GR-C3 hyperactivity

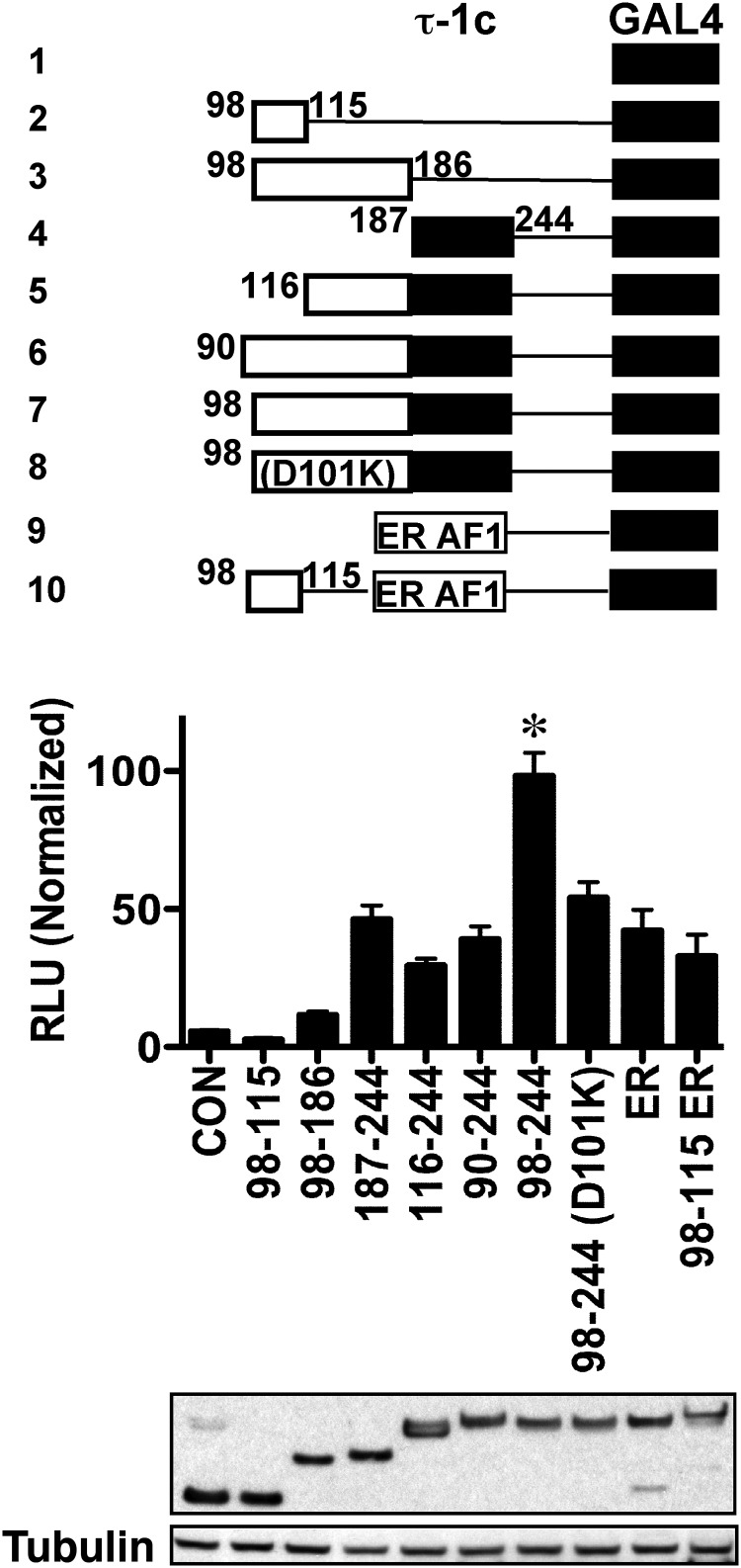

Previous findings indicated that the core region of τ-1 lies within residues 187 to 244. Because GR-A, -B, -C1, -C2, and -C3 isoforms all have the intact τ-1 core domain, we sought novel motifs outside of this core region that are critical for the enhanced activity of the GR-C3 isoform. We performed a series of truncations between the residues 98 and 186. The boundaries of the truncations were based on the secondary structures in the GR N terminus predicted by various methods including NetSurfP (25), Jpred3 (26), and PHDacc (27) and by using published reports (28). Fragment 106 to 112 is predicted to have a β-sheet and fragment 116 to 127 is predicted to have an α-helix. As indicated in Figure 3, truncation scanning analyses revealed that residues between 98 and 116 are necessary in the hyperactivity of the GR-C3 isoform. Deletions of various segments between residues 98 and 186 all reduced the activity of the GR-C3 isoform. The minimal fragment critical for the hyperactivity of the GR-C3 isoform was thus located to residues 98 to 115. Deletion of residues 98 to 115 (M116 in Figure 3) results in a more than 50% reduction in activity, comparable to that of GR-A, -B, -C1, and -C2 isoforms (Figure 1). As predicted, deleting the τ-1 core completely abolished the activity of the receptor (M245 in Figure 3). To date, the structure of the GR N terminus is not resolved although an organized N terminus after ligand binding has been suggested (29–32). Our results suggest that residues 98 to 115 may comprise a structural and functional motif that is critical for GR activity.

Figure 3.

The heightened activity of the GR-C3 isoform is dependent on residues 98 to 115. Serial truncation of the N-terminus was introduced in the GR-C3 isoform. The fragment deleted was immediately upstream of the start codons (M) indicated. A representative Western blot of the protein levels is shown. Luciferase activities (percentage, normalized to protein levels) of the constructs represented by the solid bars are significantly less than those of the GR-C3 isoform; P < .05, ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests. RLU, relative light unit.

Charged and polar residues underlie the hyperactivity of the GR-C3 isoform

We sought to identify the critical residues responsible for the enhanced activity of the GR-C3 isoform. As indicated in Figure 4, there are several charged and polar residues within the segment 98 to 115. To determine whether these residues are critical for the receptor function, we performed site-directed mutagenesis. Mutations Asp101Lys, Asp101Ala, and Gln106,107Leu all reduced the activity of the GR-C3 isoform by approximately 50%. These findings further support the hypothesis that there may be a functional motif between residues 98 and 115 that enhances the activity of the τ-1 core. In contrast, mutations further downstream did not reduce the activity of the GR-C3 isoform. Unexpectedly, Ser113, 114Ala, which blocks phosphorylation at Ser113, did not have effects on the receptor activity.

Figure 4.

Charged and polar residues are critical for the heightened activity of the GR-C3 isoform. Asp101, Gln106, and Gln107 but not other mutations inhibited the activity of the GR-C3 isoform. Consistent with the observation that fragment 98 to 115 is critical for the enhanced activity of the GR-C3 isoform (Figure 3), mutations of residues downstream of residue 115 did not reduce the activity of the GR-C3 isoform. A representative Western blot of the protein levels is shown and luciferase activities (percentage) were normalized to protein levels. *, Significantly less than the activity of the GR-C3 isoform; P < .05, ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests. RLU, relative light unit.

Motif 98 to 115 does not have independent transactivation activity

By definition, an independent functional domain such as τ-1 can maintain its transcriptional activity in a different context. Thus, placing the τ-1 core next to the yeast GAL4 DBD, out of the context of GR, transferred the transactivation function of the τ-1 core to a GAL4-responsive reporter (construct 4 in Figure 5). We determined whether motif 98 to 115 contains an independent functional domain. A chimera construct with the GAL4 DBD showed that residues 98 to 115 do not contain any independent transactivation activity (construct 2 in Figure 5). Rather, residues upstream of the τ-1 core up to Met98 probably function as a facilitatory motif (construct 7 in Figure 5). In contrast, additional residues upstream of Met98 blocked the activity-enhancing ability of residues 98 to 115 (constructs 5 and 6 in Figure 5), supporting the observations above that the activity of the GR-C3 isoform can be blocked by upstream residues. Similarly, mutation Asp101Lys abolished the τ-1-enhancing activity of residues 98 to 186 (construct 8 in Figure 5). The transactivation enhancing activity of the motif 98 to 115 seems to be specifically for GR because this motif is not found in other transcription factors and addition of this motif to ER AF1 (construct 10 in Figure 5) did not enhance the activity of ER AF1 (construct 9 in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Motif 98 to 186 enhances the activity of the τ-1 core. COS-1 cells were transfected with pBind and pG5luc. pBind constructs express GR or ER and GAL4 DBD chimeras as well as Renilla luciferase. pG5luc expresses firefly luciferase driven by 5 copies of GAL4 response elements. Transfection procedure and luciferase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Fragment 98 to 115 (construct 2) had no independent transactivation activity as demonstrated in a GR GAL4 DBD chimera construct. However, the addition of residues 98 to 186 (construct 7) enhanced the activity of τ-1 core (construct 4). The fragment 98 to 186 harboring the mutation Asp101Lys (construct 8) did not enhance the activity of the τ-1 core, further demonstrating the importance of this charged residue. Addition of residues upstream of the GR-C3 isoform (constructs 5 and 6) did not increase the activity of the τ-1 core, confirming the role of steric hindrance from the region upstream of Met98. The addition of residues 98 to 115 to ER AF1 (construct 10) did not enhance transactivation. A representative Western blot of the protein levels is shown. Luciferase activities (percentage) were normalized to protein levels. *, Significantly greater than construct 4 (187 to 244-GAL4); ANOVA, P < .05, Tukey post-hoc tests. CON, control; RLU, relative light unit.

Replacing Asp101 suppresses the apoptosis-inducing activity of the GR-C3 isoform

To further demonstrate the critical role of Asp101 in the activity of the GR-C3 isoform, we performed apoptosis analyses in U-2 OS cells stably expressing the GR-C3 isoform and those stably expressing the GR-C3 isoform harboring the Asp101Lys mutation. The expression levels of the GR-C3 isoform and that of the Asp101Lys mutant were comparable (Figure 6A). We found that Asp101Lys mutation reduced the ability of the GR-C3 isoform to mediate glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Figure 6B). U-2 OS cells stably expressing the GR-C3 isoform or the GR-C3 (Asp101Lys) mutants were treated with vehicle or DEX (100 nM) for 48 hours. Previous studies indicated that apoptosis [increased caspase activity, chromatin condensation, DNA, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage] begins 14 to 20 hours after DEX exposure and peaks at 48 hours of treatment (8). We observed a marked decrease in the amount of cell death (as measured by propidium iodide and annexin V labeling) in cells expressing the Asp101Lys mutant.

Figure 6.

Residue Asp101 is critical for the function of the GR-C3 isoform. A, A representative Western blot shows that comparable levels of receptor proteins were expressed in 2 clones of U-2 OS cells expressing the GR-C3 isoform and in 2 additional clones expressing the GR-C3 isoform harboring the Asp101Lys mutation. B, Propidium iodide (PI) (or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI]) staining of dead cells and annexin V staining of apoptotic cells indicated that the Asp101Lys mutations impaired the glucocorticoid-induced cell death. Histograms and dot plots are from flow cytometric analyses. Bar graphs are averages of at least four experiments. C, Real-time RT PCR experiments show that granzyme A (GZMA) expression was impaired by Asp101Lys mutation (n = 2). D, Immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG and immunoblotting (IB) with anti-GR showed that Asp101Lys did not impair GR interaction with CBP (n = 3). E, ChIP assay demonstrated that GR binding to DNA was not impaired by the mutation. In contrast, CBP and p300, but not BRG1, recruitment in the context of DNA was significantly inhibited by Asp101Lys mutation. Shown are representatives of 3 experiments. Bar graphs are averages of real-time PCR quantification. *, Significantly less than the GR-C3 isoform (DEX); P < .05, ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests (B) or Student's t tests (C, E). CON, control.

ChIP analysis indicates that Asp101 is responsible for coregulator recruitment

The decreased apoptosis-inducing ability of GR-C3 Asp101Lys was correlated to the decreased expression of granzyme A (Figure 6C). The truncation scanning studies discussed above delineated the boundary of the τ-1 enhancing motif to residues 98 to 115. One potential means for motif 98 to 115 to act as a facilitatory motif that enhances the activity of τ-1 core is via enhancement of coregulator recruitment. To test this hypothesis, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments and found that GR-C3 and GR C3 Asp101Lys had similar abilities to interact with CBP (Figure 6D). However, ChIP analyses showed that in the context of DNA, the amount of CBP and p300 recruitment onto the granzyme GRE (8) was blunted significantly in cells carrying the mutated GR-C3 isoform (Figure 6E). The ability of GR to bind DNA and to recruit other cofactors such as BRG1 (Figure 6E) and GRIP1 (not shown) was not impaired in GR-C3 Asp101Lys. Thus, Asp101 in the N terminus underlies the hyperactivity of the GR-C3 isoform via enhancement of selective coregulator (such as CBP and p300) recruitment onto the DNA binding sites.

Discussion

We found a novel motif in the N terminus of the GR that enhances the activity of the τ-1 domain and that endows the GR translational isoforms with distinct transactivation activities. This motif located between residues 98 and 115 enables the GR-C3 isoform to have transactivation activity and proapoptotic effects twice as high as those of the other GR isoforms. Specific charged and polar residues and their role in coregulator recruitment underlie the ability of this motif to enhance τ-1 activity. Tissue-specific effects of glucocorticoids remain enigmatic after much research. Tissue-selective expression of cofactors and glucocorticoid-metabolizing enzymes such as 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 have been reported to contribute tissue specificity of glucocorticoid responses (33, 34). We propose, in addition, that GR isoforms play a key role in the tissue-specific glucocorticoid responses. Several lines of evidence support this notion. First, GR isoforms have tissue-specific and cell maturational and activational stage-specific expression patterns (5–7). Second, GR isoforms have unique gene targets and proapoptotic functions (5–8, 35). The findings reported here further demonstrated a molecular basis of the functional differences among GR isoforms. This study does not examine the transrepression activity of the GR isoforms. Our previous results indicate that GR isoforms suppress nuclear factor-κB reporter genes with similar efficacy (8). In addition, inflammatory responses, eg, lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF, IL-8, and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, are blocked by all GR isoforms in multiple cell types (6–8). These findings are consistent with findings from other groups, indicating that the transrepression activity of GR relies mainly on the DBD and LBD, which are present in all GR isoforms (36–38).

Posttranslational modifications do not explain the distinct activities of GR isoforms. Eleven phosphorylation sites on human GR have been identified at Thr8, Ser 45, Ser113, Ser134, Ser141, Ser203, Ser211, Ser226 Ser234, Ser267, and Ser404 (39–43). Phosphorylation of Ser211 by cyclin-dependent kinases has been reported to enhance GR activity, whereas phosphorylation of Ser226 by MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase and that of Ser404 by serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 3 has been demonstrated to inhibit GR activity (39, 41, 44–48). These phosphorylation sites do not contribute to the hyperactivity of the GR-C3 isoform because the GR-A, -B, -C1, -C2, and -C3 isoforms share most of these phosphorylation sites. The GR-C3 isoform lacks Thr8 and Ser45, which, however, does not explain the hyperactivity of the GR-C3 isoform either because 2 other isoforms lacking Thr8 and Ser45, the GR-C1 and -C2 isoforms, and the 2 isoforms containing Thr8 and/or Ser45, the GR-A and -B isoforms, all have similar activities that are 50% lower than that of the GR-C3 isoform. Thus, phosphorylation does not explain the heightened activity of the GR-C3 isoform. Rather, unobstructed motif 98 to 115 was the underlying mechanism for the enhanced activity of the GR-C3 isoform. To further confirm this finding, we found that blocking the phosphorylation of Ser113 did not change the activity of the GR-C3 isoform (Figure 4). In contrast, charged and polar residues Asp101 and Gln106, 107 are essential for the enhanced activity of the GR-C3 isoform.

Between the τ-1 core and DBD of GR lie the synergy control (SC) motifs that are essential for the behavior of GR on composite GRE such as that in the MMTV promoter (49). Sumoylation underlies the activity of the SC motifs. Three consensus sumoylation sites have been identified within the GR, and this posttranslational modification seems to affect the transcriptional activity of the receptor as well (50–52). All GR isoforms except the GR-D isoforms contain the 3 known sumoylation sites. However, sumoylation is not likely to contribute to the differences in the activity among the GR-C isoforms because they contain identical sumoylation sites and SC motifs. Similarly, nitrosylation (53, 54) and the redox status at the 20 cysteine residues toward the GR C terminus (55–57) do not provide an explanation for the differential activities of GR isoforms. The GR is degraded through the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and/or E3 ubiquitin ligase–dependent unbiquitin-proteasome pathway (58). When the turnover rate of GR is decreased by pharmacological inhibition of proteasome activity, GR activity is increased. We previously reported that the turnover rates are similar among the GR isoforms (8), indicating that other mechanisms contribute to the differential activity of the GR isoforms.

We found that steric hindrance of motif 98 to 115 is probably the mechanism for the lower activity of the GR-A, -B, -C1, and -C2 isoforms. Mutation analyses and tagging with unrelated sequences revealed that this hindrance is not likely to be dependent on specific sequences. In addition, Asp101 has been found to be critical in coregulator recruitment in the context of DNA. Our results are in line with the literature indicating the existence of functional structures in the N terminus of GR, and residues flanking the AF1 may play an inhibitory role (29–32, 59–61). The GR N-terminal domain probably regulates conformations of DBD and LBD via intermodular interaction (62) as reported for other nuclear receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and ER (63, 64). Motif 98 to 115, when unobstructed, may enhance DNA context-dependent recruitment of CBP and p300 as demonstrated by ChIP analyses.

A third transactivation domain has been reported in the progestin receptor (PR)-B isoform (65–67). This PR-B isoform upstream function (B-upstream segment) prompted us to examine whether motif 98 to 115 is a previously undiscovered independent transactivation domain. We found that linking this motif may enhance the activity of the τ-1 core domain. There are 2 requirements for this enhancement. One is the presence of this motif not having any upstream obstruction. The other requirement is the presence of the charged residues because mutation Asp101Lys lost the enhancing ability. Different from the B-upstream segment in PR-B, motif 98 to 115 does not contain any independent activity as demonstrated by the motif 98 to 115 and GAL4 chimera construct. The transactivation activity of motif 98 to 115 is specific for GR because this motif was not found in other transcription factors, and it did not enhance the activity of ER AF1.

Glucocorticoids are essential in treating inflammation and cancer. However, severe side effects such as hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal suppression, metabolic syndrome, and osteoporosis limit their use. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the tissue-selective actions of GR isoforms will help us in designing new glucocorticoid drugs with increased efficacy and reduced side effects. GR isoform-selective compounds may provide a new direction for designing glucocorticoids with tissue-selective actions. Drugs that selectively regulate the expression of GR isoforms may be also useful. Our findings support the fact that GR isoforms have distinct functions, and they may underlie the tissue-selective actions of glucocorticoids.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01HL094558 to N.Z.L.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- CBP

- cAMP binding protein–binding protein

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DEX

- dexamethasone

- DBD

- DNA binding domain

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- LBD

- ligand binding domain

- MMTV

- mouse mammary tumor virus

- PR

- progestin receptor

- SC

- synergy control

- YFP

- yellow fluorescence protein.

References

- 1. Rhen T, Cidlowski JA. Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids—new mechanisms for old drugs. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1711–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lu NZ, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid receptor isoforms generate transcription specificity. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oakley RH, Sar M, Cidlowski JA. The human glucocorticoid receptor β isoform. Expression, biochemical properties, and putative function. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9550–9559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oakley RH, Webster JC, Sar M, Parker CR, Jr, Cidlowski JA. Expression and subcellular distribution of the β-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology. 1997;138:5028–5038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lu NZ, Cidlowski JA. Translational regulatory mechanisms generate N-terminal glucocorticoid receptor isoforms with unique transcriptional target genes. Mol Cell. 2005;18:331–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cao Y, Bender IK, Konstantinidis AK, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor translational isoforms underlie maturational stage-specific glucocorticoid sensitivities of dendritic cells in mice and humans. Blood. 2013;121:1553–1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu I, Shin SC, Cao Y, et al. Selective glucocorticoid receptor translational isoforms reveal glucocorticoid-induced apoptotic transcriptomes. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu NZ, Collins JB, Grissom SF, Cidlowski JA. Selective regulation of bone cell apoptosis by translational isoforms of the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7143–7160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giguère V, Hollenberg SM, Rosenfeld MG, Evans RM. Functional domains of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Cell. 1986;46:645–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hollenberg SM, Evans RM. Multiple and cooperative trans-activation domains of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Cell. 1988;55:899–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Danielsen M, Northrop JP, Jonklaas J, Ringold GM. Domains of the glucocorticoid receptor involved in specific and nonspecific deoxyribonucleic acid binding, hormone activation, and transcriptional enhancement. Mol Endocrinol. 1987;1:816–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Godowski PJ, Picard D, Yamamoto KR. Signal transduction and transcriptional regulation by glucocorticoid receptor-LexA fusion proteins. Science. 1988;241:812–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luisi BF, Xu WX, Otwinowski Z, Freedman LP, Yamamoto KR, Sigler PB. Crystallographic analysis of the interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with DNA. Nature. 1991;352:497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bledsoe RK, Montana VG, Stanley TB, et al. Crystal structure of the glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding domain reveals a novel mode of receptor dimerization and coactivator recognition. Cell. 2002;110:93–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ding XF, Anderson CM, Ma H, et al. Nuclear receptor-binding sites of coactivators glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) and steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1): multiple motifs with different binding specificities. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:302–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. Expanding functional diversity of the coactivators. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:126–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dahlman-Wright K, Baumann H, McEwan IJ, et al. Structural characterization of a minimal functional transactivation domain from the human glucocorticoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1699–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dahlman-Wright K, Almlöf T, McEwan IJ, Gustafsson JA, Wright AP. Delineation of a small region within the major transactivation domain of the human glucocorticoid receptor that mediates transactivation of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1619–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henriksson A, Almlöf T, Ford J, McEwan IJ, Gustafsson JA, Wright AP. Role of the Ada adaptor complex in gene activation by the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3065–3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Almlöf T, Wallberg AE, Gustafsson JA, Wright AP. Role of important hydrophobic amino acids in the interaction between the glucocorticoid receptor tau 1-core activation domain and target factors. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9586–9594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Almlöf T, Gustafsson JA, Wright AP. Role of hydrophobic amino acid clusters in the transactivation activity of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:934–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ford J, McEwan IJ, Wright AP, Gustafsson JA. Involvement of the transcription factor IID protein complex in gene activation by the N-terminal transactivation domain of the glucocorticoid receptor in vitro. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1467–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao X, Sternsdorf T, Bolger TA, Evans RM, Yao TP. Regulation of MEF2 by histone deacetylase 4- and SIRT1 deacetylase-mediated lysine modifications. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8456–8464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Petersen B, Petersen TN, Andersen P, Nielsen M, Lundegaard C. A generic method for assignment of reliability scores applied to solvent accessibility predictions. BMC Struct Biol. 2009;9:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rost B, Sander C. Conservation and prediction of solvent accessibility in protein families. Proteins. 1994;20:216–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cole C, Barber JD, Barton GJ. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W197–W201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumar R, Thompson EB. Influence of flanking sequences on signaling between the activation function AF1 and DNA-binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;496:140–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kumar R, Volk DE, Li J, Lee JC, Gorenstein DG, Thompson EB. TATA box binding protein induces structure in the recombinant glucocorticoid receptor AF1 domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16425–16430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kumar R, Thompson EB. Transactivation functions of the N-terminal domains of nuclear hormone receptors: protein folding and coactivator interactions. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumar R, Lee JC, Bolen DW, Thompson EB. The conformation of the glucocorticoid receptor af1/tau1 domain induced by osmolyte binds co-regulatory proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18146–18152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kumar R, Baskakov IV, Srinivasan G, Bolen DW, Lee JC, Thompson EB. Interdomain signaling in a two-domain fragment of the human glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24737–24741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu J, Li Q. Review of the in vivo functions of the p160 steroid receptor coactivator family. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1681–1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Funder JW, Pearce PT, Smith R, Smith AI. Mineralocorticoid action: target tissue specificity is enzyme, not receptor, mediated. Science. 1988;242:583–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gross KL, Oakley RH, Scoltock AB, Jewell CM, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid receptor α isoform-selective regulation of antiapoptotic genes in osteosarcoma cells: a new mechanism for glucocorticoid resistance. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1087–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McKay LI, Cidlowski JA. Cross-talk between nuclear factor-kappa B and the steroid hormone receptors: mechanisms of mutual antagonism. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Caldenhoven E, Liden J, Wissink S, et al. Negative cross-talk between RelA and the glucocorticoid receptor: a possible mechanism for the antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:401–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scheinman RI, Gualberto A, Jewell CM, Cidlowski JA, Baldwin AS., Jr Characterization of mechanisms involved in transrepression of NF-κB by activated glucocorticoid receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:943–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Z, Frederick J, Garabedian MJ. Deciphering the phosphorylation “code” of the glucocorticoid receptor in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26573–26580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dephoure N, Zhou C, Villén J, et al. A quantitative atlas of mitotic phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10762–10767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Galliher-Beckley AJ, Williams JG, Collins JB, Cidlowski JA. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β-mediated serine phosphorylation of the human glucocorticoid receptor redirects gene expression profiles. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:7309–7322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Galliher-Beckley AJ, Williams JG, Cidlowski JA. Ligand-independent phosphorylation of the glucocorticoid receptor integrates cellular stress pathways with nuclear receptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4663–4675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ismaili N, Garabedian MJ. Modulation of glucocorticoid receptor function via phosphorylation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1024:86–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rogatsky I, Logan SK, Garabedian MJ. Antagonism of glucocorticoid receptor transcriptional activation by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2050–2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Szatmáry Z, Garabedian MJ, Vilcek J. Inhibition of glucocorticoid receptor-mediated transcriptional activation by p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43708–43715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Itoh M, Adachi M, Yasui H, Takekawa M, Tanaka H, Imai K. Nuclear export of glucocorticoid receptor is enhanced by c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated phosphorylation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2382–2392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Davies L, Karthikeyan N, Lynch JT, et al. Cross talk of signaling pathways in the regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor function. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1331–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Beck IM, Vanden Berghe W, Vermeulen L, Yamamoto KR, Haegeman G, De Bosscher K. Crosstalk in inflammation: the interplay of glucocorticoid receptor-based mechanisms and kinases and phosphatases. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:830–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Holmstrom SR, Chupreta S, So AY, Iñiguez-Lluhí JA. SUMO-mediated inhibition of glucocorticoid receptor synergistic activity depends on stable assembly at the promoter but not on DAXX. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2061–2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tian S, Poukka H, Palvimo JJ, Jänne OA. Small ubiquitin-related modifier-1 (SUMO-1) modification of the glucocorticoid receptor. Biochem J. 2002;367:907–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Le Drean Y, Mincheneau N, Le Goff P, Michel D. Potentiation of glucocorticoid receptor transcriptional activity by sumoylation. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3482–3489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Holmstrom S, Van Antwerp ME, Iñiguez-Lluhi JA. Direct and distinguishable inhibitory roles for SUMO isoforms in the control of transcriptional synergy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15758–15763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Galigniana MD, Piwien-Pilipuk G, Assreuy J. Inhibition of glucocorticoid receptor binding by nitric oxide. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Paul-Clark MJ, Roviezzo F, Flower RJ, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor nitration leads to enhanced anti-inflammatory effects of novel steroid ligands. J Immunol. 2003;171:3245–3252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hutchison KA, Mati G, Meshinchi S, Bresnick EH, Pratt WB. Redox manipulation of DNA binding activity and BuGR epitope reactivity of the glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10505–10509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Makino Y, Okamoto K, Yoshikawa N, et al. Thioredoxin: a redox-regulating cellular cofactor for glucocorticoid hormone action. Cross talk between endocrine control of stress response and cellular antioxidant defense system. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2469–2477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Okamoto K, Tanaka H, Ogawa H, et al. Redox-dependent regulation of nuclear import of the glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10363–10371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wallace AD, Cidlowski JA. Proteasome-mediated glucocorticoid receptor degradation restricts transcriptional signaling by glucocorticoids. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42714–42721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wallberg AE, Flinn EM, Gustafsson JA, Wright AP. Recruitment of chromatin remodelling factors during gene activation via the glucocorticoid receptor N-terminal domain. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:410–414 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wallberg AE, Neely KE, Hassan AH, Gustafsson JA, Workman JL, Wright AP. Recruitment of the SWI-SNF chromatin remodeling complex as a mechanism of gene activation by the glucocorticoid receptor tau1 activation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2004–2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wallberg AE, Neely KE, Gustafsson JA, Workman JL, Wright AP, Grant PA. Histone acetyltransferase complexes can mediate transcriptional activation by the major glucocorticoid receptor activation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5952–5959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yoshikawa N, Yamamoto K, Shimizu N, Yamada S, Morimoto C, Tanaka H. The distinct agonistic properties of the phenylpyrazolosteroid cortivazol reveal interdomain communication within the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1110–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shao D, Rangwala SM, Bailey ST, Krakow SL, Reginato MJ, Lazar MA. Interdomain communication regulating ligand binding by PPAR-γ. Nature. 1998;396:377–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gandini O, Kohno H, Curtis S, Korach KS. Two transcription activation functions in the amino terminus of the mouse estrogen receptor that are affected by the carboxy terminus. Steroids. 1997;62:508–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sartorius CA, Melville MY, Hovland AR, Tung L, Takimoto GS, Horwitz KB. A third transactivation function (AF3) of human progesterone receptors located in the unique N-terminal segment of the B-isoform. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:1347–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tung L, Abdel-Hafiz H, Shen T, et al. Progesterone receptors (PR)-B and -A regulate transcription by different mechanisms: AF-3 exerts regulatory control over coactivator binding to PR-B. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2656–2670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tung L, Shen T, Abel MG, et al. Mapping the unique activation function 3 in the progesterone B-receptor upstream segment. Two LXXLL motifs and a tryptophan residue are required for activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39843–39851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]