Abstract

Recent advances in sequencing technologies have revealed that the genome is extensively transcribed, yielding a large repertoire of noncoding RNAs. These include long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), mRNA-like molecules that do not code for proteins, which are emerging as a new class of RNAs that play important roles in a variety of cellular processes. Ongoing studies are revealing new insights about lncRNAs, including their physiological functions, disease relationships, and molecular mechanisms of action. Characterized lncRNAs have been shown to interact with and modulate the activity of other RNAs and protein partners, leading to alterations in transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulatory processes. In this review, we summarize the key features of lncRNAs, their molecular mechanisms of action, biological functions, and therapeutic implications, particularly as they apply to the field of molecular endocrinology. In addition, we provide a brief overview of how molecular biologists are beginning to probe the identity, mechanisms, and functions of this emerging class of RNA molecules.

The “central dogma” of biochemistry posits that (1) DNA carries and propagates genetic information, (2) proteins play important structural or functional roles essential for all aspects of life, and (3) RNA mediates information transfer from DNA to proteins (1). With respect to the latter, messenger RNAs (mRNAs) act as intermediary molecules between DNA and proteins, small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) function primarily in the processing of mRNAs in the nucleus, and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and transfer RNAs (tRNAs) comprise the machinery that translates mRNAs into proteins. This limited view of the functions of RNA has been altered dramatically over the past decade with the discovery that animal genomes are subject to widespread transcription, giving rise to a wide variety of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) that play key roles in cellular functions beyond those historically ascribed to RNA (2–5).

In this review, we discuss the identification and functional characterization of one class of ncRNAs, namely long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), whose functions are just beginning to be understood. We summarize the key features of lncRNAs, as well as their mechanisms of action, biological functions, and therapeutic implications, particularly those aspects that apply to molecular endocrinology. We also outline the major approaches and strategies used by molecular biologists to query the functions of lncRNAs.

The Emerging New World of LncRNAs

LncRNAs are mRNA-like molecules that do not typically code for proteins. Although the existence of individual lncRNAs, such as H19 and Xist (X inactive-specific transcript) (6, 7), has been known since the early 1990s, lncRNAs have generally been considered anomalies until recently. Advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies in the 2000s led to large-scale transcriptome mapping and genome annotation projects, such as the Functional Annotation of the Mammalian Genome (FANTOM) project, which has identified more than 10,000 lncRNAs in mouse (2). These studies have revealed the prevalence and pervasiveness of ncRNAs, such as lncRNAs, in the genome (3–5, 8). In the decade of research that followed the initial explosion of mapping projects, the biological functions and mechanisms of action of this new class of ncRNAs have gradually been elucidated. Nevertheless, lncRNAs remain one of the least understood class of ncRNAs, and many questions remain regarding all aspects of their biology:

How does the manner in which lncRNAs are transcribed, processed, and regulated differ from that of other RNAs?

Are lncRNAs evolutionarily conserved, both in terms of their primary sequences and secondary structures?

Are all lncRNAs functional? Which ones have detectable biological functions in cells or in the whole organism?

Does the pervasive transcription that generates the lncRNA transcripts play a regulatory role distinct from the steady-state accumulation of the lncRNAs?

Can lncRNAs be exploited for clinical applications and therapeutics?

These questions remain unanswered or incompletely answered. Nevertheless, lncRNAs as a group present promising opportunities for broadening our fundamental understanding of molecular biology and opening new doors to effective therapeutic strategies.

Definition and Characteristics of LncRNAs

Although they are structurally similar in many ways, lncRNAs differ in a fundamental way from mRNAs: they do not typically code for functional proteins (although they may code for short polypeptides of unknown function) (9–13). Instead, functional lncRNAs mediate their molecular actions through their RNA forms, as opposed to translated proteins. Nevertheless, being “long” ncRNAs, they are more similar to mRNAs in terms of their transcript length. In fact, to distinguish them from small ncRNA molecules, such as rRNAs, tRNAs, snRNAs, and microRNAs, researchers have adopted a convenient length cutoff of 200 nucleotides (5, 9, 10, 12, 14–18). Thus, the working definition of lncRNAs can be distilled as follows: they are endogenous RNA molecules >200 nucleotides in length in their mature form that do not code for functional proteins.

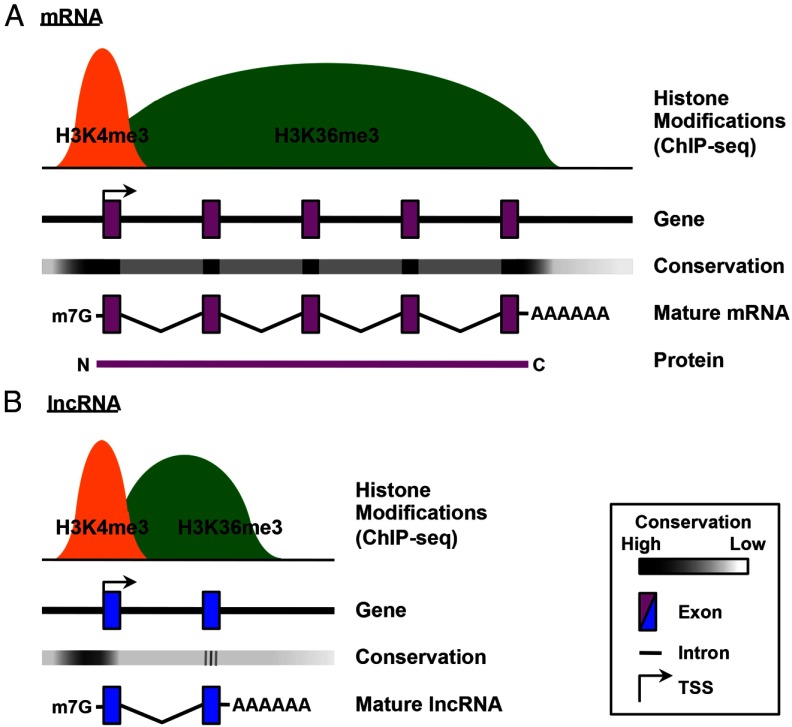

lncRNAs share other similarities with mRNAs. Most of them are transcribed by RNA polymerase II (10, 17, 19, 20), probably due to the processivity required for producing longer RNAs. Consistent with being polymerase II transcripts, most lncRNAs are 5′-capped and 3′-polyadenylated, and many of them are spliced at classic splice site sequences (10, 18, 20, 21) (Figure 1). As a result, RNA-Seq with poly(A)-enriched RNA has been a common approach in large-scale lncRNA identification and annotation projects (22, 23). Similar to the genes encoding mRNAs, the genes encoding lncRNAs often display an enrichment of histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) at their promoters and histone 3 lysine 36 trimethylation (H3K36me3) across their gene bodies (12, 17, 20, 24, 25) (Figure 1). H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 are chromatin signatures characteristic of active gene promoters and actively transcribed regions, respectively (26). Therefore, the combination of these marks, or K4–K36 domains, coupled with evidence of mature RNA transcripts, has been used by several research groups in their attempts to identify lncRNAs on a genome-wide scale (19, 27).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the gene and transcript structures of mRNAs and lncRNAs. Schematic representations of the gene and transcript structures of mRNAs (A) and lncRNAs (B), highlighting the similarities and differences, are shown. Similarities include: (1) 5′,7-methylguanosine (m7G) capped, spliced, and polyadenylated (AAAAAA) transcripts and (2) histone modification signatures indicative of active promoters (H3K4me3) and actively transcribed gene bodies (H3K36me3) for actively transcribed genes. Differences include fewer exons, shorter transcripts, lower gene conservation, and lack of coding potential for lncRNAs. ChIP-seq, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing; TSS, transcription start site.

On the other hand, lncRNAs show distinct differences from mRNAs, beyond being noncoding. For example, lncRNAs are on average shorter than mRNAs and have fewer exons and introns (18, 28) (Figure 1). Moreover, lncRNAs show lower sequence conservation than both mRNAs and microRNAs (Figure 1). Although much less conserved than the exons of mRNAs, exons of lncRNAs are relatively more conserved than introns of mRNAs and lncRNAs and ancient repeat sequences (9, 18, 19, 28–30). Furthermore, the conservation of lncRNA gene promoters is comparable to that of mRNA gene promoters, suggesting similar modes of transcriptional regulation (18). In addition, short patches of conserved sequences are observed along the length of lncRNAs, and some lncRNAs have been shown to contain important functional motifs in gene-specific studies (27). Further exploration of the phylogenetic properties of lncRNAs is likely to provide new insights into genome evolution (18).

A number of large-scale studies have shown that lncRNAs are expressed at significantly lower steady-state levels than protein-coding mRNAs and their expression is more tissue and developmentally restricted (18, 23). In fact, the differential expression of lncRNAs across multiple tissues or along a developmental or signal-regulated time axis has been used in a number of studies to infer potential functions for a subset of lncRNAs that display the highest spatial or temporal specificity (31–33). In terms of their subcellular localization and trafficking, mRNAs are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (or the rough endoplasmic reticulum for mRNAs encoding membrane-associated or secreted proteins) for translation. When mRNA-encoded proteins are needed in the nucleus, they are transported back to the nucleus from the cytoplasm. LncRNAs, on the other hand, function as RNA molecules and do not need to be translated. Therefore, their subcellular localization for function is not necessarily restricted. Although lncRNAs as a class of ncRNAs are enriched in the nucleus, a conclusion supported by the GENCODE v7 catalog of human lncRNAs (18), individual lncRNAs with nuclear functions may be distributed in the nucleus and cytoplasm. For example, HOTAIR, GAS5, and PINC, 3 lncRNAs that are thought to regulate transcription, are found in the nucleus and cytoplasm (see below).

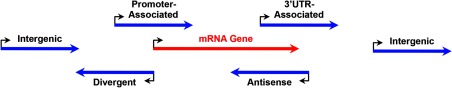

As illustrated in the descriptions above, lncRNAs are similar to mRNAs in several ways but differ in multiple ways as well. As researchers study this new class of ncRNAs in more detail, mRNAs serve as a useful reference point. Subclassification of lncRNAs into smaller groups has been based on the location of their genes in the genome relative to those of annotated mRNA genes and other genomic features (12, 34) (Figure 2). Traditionally, to ensure a clear distinction from protein-coding mRNAs, researchers have focused on the study of lncRNAs whose genes reside in intergenic regions and do not overlap with annotated coding gene loci (hence, they are also referred to as long intergenic ncRNAs [lincRNAs]) (19, 22, 23, 27, 35). Nevertheless, methods with improved sensitivity and resolution have facilitated the discovery of an expanded universe of lncRNA genes (18, 25, 36). A considerable proportion of them are “genic,” including (1) natural antisense transcripts, which run in the direction opposite to that of known mRNA genes and overlap with their gene bodies (36), (2) divergent lncRNAs, which originate from the opposite DNA strand, but use the same promoters as mRNAs, extending in the opposite direction (25), and (3) promoter-associated lncRNAs and 3′-untranslated region–associated lncRNAs, grouped based on their proximal location relative to the start and end of mRNAs genes (Figure 2) (37, 38). Various hypotheses have linked each of these classes of lncRNAs to a specific mode of action, but the extent to which gene location and molecular function are associated and whether such location-based classification holds real biological meaning remains to be determined.

Figure 2.

Location and orientation of lncRNA genes relative to mRNA genes. Schematic representations of the location and orientation of lncRNA genes (blue arrows) relative to those of mRNA genes (red arrow). Bent arrows indicate the transcription start sites (TSSs) of the genes. The arrowheads on the blue and red arrow indicate the direction of transcription by RNA polymerase II for the lncRNA and mRNA genes.

Molecular Functions of LncRNAs

Despite the recent success in identifying lncRNAs, determining their molecular and physiological functions has been considerably more challenging. A recurring theme for those lncRNAs that have been characterized in detail is that, at the molecular level, they function in the regulation of gene expression. They bind proteins, base pair with other RNA molecules, and modulate the activity of chromatin modifiers, transcription factors, mRNA-binding proteins, and microRNAs to achieve their effects. Some of these activities are described in the sections below.

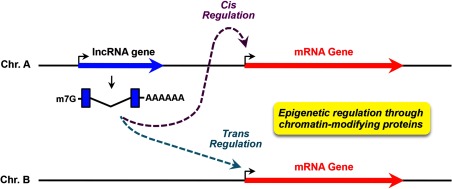

Epigenetic regulation through chromatin-modifying proteins

LncRNAs have been implicated in cis-acting epigenetic gene regulation, which is arguably the best-defined molecular function of lncRNAs (Figure 3). The well-characterized 17-kb lncRNA Xist plays a central role in X chromosome inactivation (XCI) (39–42). Xist is transcribed from the future inactive X chromosome (Xi) and binds to the YY1 protein, as well as the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) complex, which contains the histone methyltransferase Ezh2 (43, 44). YY1 recognizes its binding site within the Xist locus, which serves as a nucleation center, and facilitates cotranscriptional docking of the Xist RNA and loading of the chromatin-modifying PRC2 complex (44). Ezh2 of the PRC2 complex primarily trimethylates histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a mark of repressive chromatin, initiating the XCI process. The Xist-PRC2 repressive complex then spreads along the Xi, promoting silencing of the entire X chromosome. Xist in XCI presents an elegant model of how a lncRNA mediates its cis-regulatory role in gene expression by guiding the recruitment of chromatin-modifying proteins, leading to epigenetic changes in the chromatin. ANRIL (antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 locus) is another lncRNA that has been suggested to function in a similar manner. However, instead of silencing an entire chromosome, ANRIL runs antisense to the tumor suppressor genes CDKN2A and CDKN2B, silencing their expression by guiding the PRC1 or PRC2 complexes to the locus, where they add repressive histone marks to chromatin (45).

Figure 3.

Cis and trans gene regulation by lncRNAs. LncRNAs can mediate epigenetic regulation through chromatin-modifying proteins in cis or trans. In cis regulation, the lncRNA acts on target genes located near the lncRNA gene. In trans regulation, the lncRNA acts on target genes located distal to the lncRNA gene, possibly on another chromosome. Blue and red arrows indicate lncRNA and mRNA genes, respectively. Bent arrows indicate the transcription start sites (TSSs) of the genes.

Whereas Xist and ANRIL mediate gene silencing by promoting the formation of repressive chromatin, the lncRNA HOTTIP (HOXA transcript at the distal tip) mediates gene activation by promoting the formation of active chromatin through the MLL complex (46), which is a histone methyltransferase that trimethylates histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) to establish an active chromatin environment at gene promoters. HOTTIP extends its influence to more distal genes through the formation of chromosome loops that bring the distal genes proximal to target gene promoters (46). Similarly, Lai et al (47) characterized lncRNAs belonging to a group of ncRNA-activating (ncRNA-a) lncRNAs, which function to activate neighboring genes or distally looped genes in cis. They showed that ncRNA-a lncRNAs interact with the Mediator coactivator complex. The interactions with Mediator are required for the formation of DNA loops that bring the ncRNA-a lncRNA genes and their target genes in proximity, as well as phosphorylation of histone 3 serine 10 (H3S10p), a histone modification that has been linked to transcriptional activation (47).

LncRNAs may have intrinsic cis-regulatory capacity, because they mediate cotranscriptional recruitment of protein factors to specific loci. Nevertheless, accumulating evidence has suggested that lncRNAs may also act in trans, extending their effects well beyond genes located proximally, perhaps even to genes on different chromosomes (Figure 3). HOTAIR (HOX transcript antisense RNA) was the first trans-acting lncRNA to be characterized. It originates from the HOXC locus on chromosome 12 in humans, but functions to repress genes in the HOXD cluster on chromosome 2 (48). At the molecular level, the 5′ domain of HOTAIR guides the PRC2 complex to target loci and its 3′ domain binds the LSD1/REST/COREST repressive complex, which demethylates H3K4me3, a mark of active transcription (49). HOTAIR also interacts with the PRC2 complex (48). Thus, it acts as a molecular scaffold to integrate the functions of 2 repressive histone-modifying complexes. Other trans-acting lncRNAs have been identified and characterized since HOTAIR was discovered.

Studies to date have shown that lncRNAs bind one or more chromatin-modifying complexes to mediate epigenetic gene regulation, either in cis or in trans. Moreover, the PRC2 complex has emerged as a common “partner in crime” (Figure 4, panel 2). Recent studies have sought to identify PRC2-interacting lncRNAs globally, also known as the “PRC2 transcriptome.” Khalil et al (50) coupled RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) (the capture of protein-bound RNAs using specific antibodies) to a microarray of lncRNA probes, whereas Zhao et al (50) subjected RIP-enriched RNAs to high-throughput sequencing. Both studies uncovered a large number of PRC2-bound lncRNAs that may repress gene expression through epigenetic modifications. Similarly, efforts are underway to identify and characterize lncRNAs that interact with other chromatin modifiers, such as components of the MLL complex.

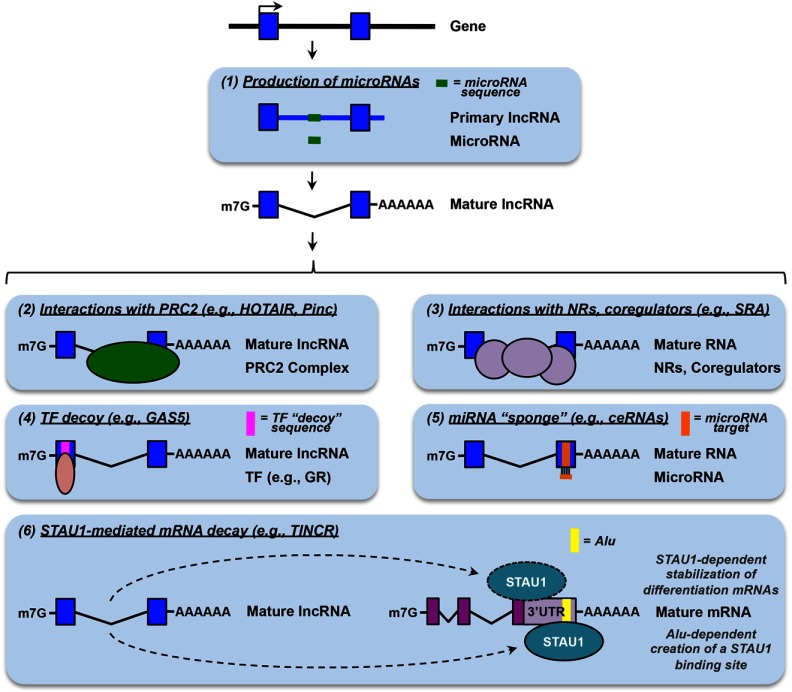

Figure 4.

Molecular mechanisms of transcriptional and posttranscriptional gene regulation by lncRNAs. LncRNAs mediate their effects on gene expression through both transcriptional (panels 2, 3, and 4) and post-transcriptional (panels 1, 5, and 6) mechanisms. The details are described in the text. The schematic diagrams use the same representations shown in the other figures.

Transcriptional regulation through transcription factors and coregulators

lncRNAs also function as transcriptional coregulators themselves, as is the case with SRA (steroid receptor RNA activator). SRA was initially identified in a screen for coregulators of progesterone receptor (PR) and was later found to associate with other nuclear receptors (NRs), including estrogen receptor (ER), androgen receptor (AR), retinoic acid receptor, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ), thyroid hormone receptor, and the orphan receptors Dax-1 and SF-1 (52). SRA also interacts with NR coactivators, such as the p160/steroid receptor coactivator proteins (53), NR corepressors, such as SLIRP and SHARP (54, 55), and other transcription factors (eg, MyoD) (56) (Figure 4, panel 3). These interactions drive gene-specific changes in transcription. Although isoforms of SRA may have some coding capacity (see below), many of the functions of SRA are mediated through its RNA structure (57). Full-length SRA contains several stem-loop substructures that bind to different protein partners (53). Thus, SRA may serve as a molecular scaffold that coordinates the functions of various transcription factors and coregulators.

GAS5 (growth arrest-specific 5) is another lncRNA that binds members of the NR family of transcription factors. It is a negative regulator of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (58). However, instead of forming stem-loop structures and serving as a molecular scaffold, a patch of GAS5's nucleotide sequence resembles a glucocorticoid response element (GRE), a DNA element that binds and recruits GR to activate hormone-induced gene expression (58). When expressed at sufficient levels, GAS5 competes with GREs and functions as a molecular decoy that prevents the GR from binding to its target sites in the genome (Figure 4, panel 4). Because several NRs share a similar response element, GAS5 may also regulate the functions of AR, PR, and the mineralocorticoid receptor through a similar mechanism. Of particular interest to the field of molecular endocrinology, SRA and GAS5 regulate the activity of NRs and are involved in the control of endocrine functions, which will be discussed in later sections.

Posttranscriptional regulation through mRNA-binding proteins and microRNAs

Historically, researchers have focused on the molecular functions of lncRNAs in transcriptional regulation and epigenetic control. A role in nuclear functions for lncRNAs is a reasonable assumption, consistent with the observation that many lncRNAs localize to the nucleus. Nevertheless, an increasing number of cytoplasmic-localized lncRNAs have been characterized recently, and some of them play a role in the posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression.

In addition to coding for microRNAs in their transcribed sequences (Figure 4, panel 1), lncRNAs interact with microRNA to modulate their posttranscriptional regulatory activities, leading to changes in the expression of cognate microRNA-targeted mRNAs. These lncRNAs have been collectively referred to as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) (Figure 4, panel 5). MicroRNAs base pair with complementary sequences on target mRNAs to guide the RNA-induced silencing (RISC) complex to its targets to mediate posttranscriptional gene silencing. In a similar way, microRNAs may base pair with complementary sequences in lncRNAs. In this case, the lncRNAs serve as ceRNAs to dilute the influence of microRNAs on their mRNA targets, mitigating the repressive effects of these microRNAs. linc-MD1, lincRNA-ROR, and PTENpg1 (phosphatase and tensin homolog pseudogene 1) are examples of lncRNAs that function as ceRNAs (59–61).

linc-MD1 is a muscle-specific lncRNA that “sponges” the effects of mir-133 and mir-135 on MAML1 and MEF2C, mRNAs encoding important transcription factors in muscle differentiation (60). In a very different biological system, lincRNA-ROR was previously identified as a modulator of reprogramming in induced pluripotent stem cells (62). More recently, Wang et al (61) demonstrated that lincRNA-ROR antagonizes the effects of differentiation-related microRNAs and functions as a ceRNA to maintain the levels of core transcription factors including NANOG, SOX2, and OCT4 in self-renewing human embryonic stem cells. The lncRNA-ceRNA network associated with PTENpg1 is even more intriguing. Although PTENpg1 itself acts as a ceRNA that sequesters a number of PTEN-targeting microRNAs (59), Johnsson et al (63) added to the network 2 PTENpg1-encoded antisense lncRNA isoforms. Whereas both isoforms function to regulate the expression of PTEN, isoform β has been shown to modulate the stability of PTENpg1, therefore influencing its microRNA sponge activity (63). Many important biological processes have multiple layers of regulation. Because PTEN is a key negative regulator of the cell survival–signaling pathway, such regulatory complexity and overlap are expected. The discovery of ceRNAs has led researchers to use bioinformatics methods to identify even more ceRNAs and their targets. By evaluating the base pairing capacity among RNA sequences and the correlative expression profiles across different RNA species, new networks of lncRNAs, microRNAs, and critical protein-coding mRNAs may be revealed.

lncRNAs have also been shown to modulate the activity of staufen 1 (STAU1), a double-stranded RNA-binding protein, in the cytoplasm by 2 different mechanisms, leading to very different outcomes (32, 64) (Figure 4, panel 6). TINCR (terminal differentiation-induced ncRNA), as the name indicates, is a lncRNA that is significantly induced during epidermal differentiation. Kretz et al (32) have shown that TINCR interacts with STAU1 and a number of differentiation mRNAs, and, together with STAU1, mediates the stabilization of these mRNAs to allow normal differentiation. Other lncRNAs function to promote STAU1-mediated mRNA decay (SMD). SMD involves the degradation of translationally active mRNAs whose 3′-untranslated regions are bound by STAU1. Half-STAU1-binding site RNAs contain Alu elements in their sequences. They form double-stranded RNA stems with Alu elements in the 3′-untranslated region of mRNAs through imperfect base pairing, creating a full STAU1 binding site to transactivate SMD on these mRNAs (64). In both cases, the lncRNAs play a role in posttranscriptional mRNA degradation through interactions with mRNAs and mRNA-binding proteins.

LncRNAs in Endocrine Functions and Diseases

The impact of lncRNAs in biological systems is just beginning to be elucidated. To date, most characterized lncRNAs have been implicated in development and differentiation or found to be involved in pathways associated with cell proliferation and cell death. These features have been summarized in other reviews (17, 34, 65–68). Here, we will focus on lncRNAs that are known or thought to play a role in endocrine systems and endocrine-related diseases, highlighting lncRNAs (1) associated with NRs, (2) involved in mammary development, and (3) involved in adipogenesis (Table 1). An improved understanding of these lncRNAs will broaden our perspectives of molecular endocrinology and may facilitate the discovery of new therapeutic agents.

Table 1.

Examples of lncRNAs in Molecular Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Development

| Group/Name | Chromosome (Species) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| A. Development-related lncRNAs | ||

| Xist (X inactive-specific transcript) | X (human) | X chromosome inactivation |

| HOTAIR (HOX transcript antisense RNA) | 12 (human) | Repression of genes in the HOXD cluster on chromosome 2 |

| B. Endocrine signaling- and metabolism-related lncRNAs | ||

| SRA (steroid receptor RNA activator) | 5 (human) | Molecular scaffold that coordinates the functions of transcription factors and coregulators; modulates steroid hormone effects on physiology and development, including mammary development |

| GAS5 (growth arrest-specific 5) | 1 (human) | Riborepressor and GR decoy that regulates glucocorticoid signaling in metabolic and inflammatory pathways |

| CTBP1-AS (C-terminal binding protein 1-anstisense) | 4 (human) | Represses the expression of CTBP1 by recruiting PSF (an RNA-binding transcriptional repressor) and histone deacetylases, which in turn promotes AR transcriptional activity |

| PR gene promoter-associated lncRNAs | 11 (human) | May modulate the expression of PR and, hence, affect transcriptional responses to progesterone, and affect downstream cell proliferation and differentiation responses in target tissues |

| Pinc (pregnancy-induced non-coding RNA) | 1 (mouse) | Regulator of mammary gland development; regulates cell survival and cell cycle progression in mammary epithelial cells |

| Zfas1 (zinc finger antisense 1) | 2 (mouse) | Regulator of mammary gland development; probably acts as a repressor to inhibit cell proliferation and differentiation |

| lnc-RAP-1, lnc-RAP-2 (lncRNAs regulated in adipogenesis 1 and 2) | X (RAP-1), 19 (RAP-2) (mouse) | Control of adipogenic gene expression programs |

LncRNAs associated with NRs

The lncRNAs described above, SRA and GAS5, are the best characterized lncRNAs in the endocrine system. Both mediate their functions as regulators of NR signaling. In cell-based studies, the SRA lncRNA binds to and coactivates PPARγ, the master regulator of the adipogenic transcription program, to promote adipocyte differentiation and to enhance glucose and lipid metabolism in differentiated adipocytes (69). It also binds and coactivates Dax-1 and SF-1 to play pivotal roles in adrenal gland function and sexual development (70, 71). Antisense morpholino-mediated knockdown of SRA in zebrafish leads to aberrant cardiac development, implicating SRA in the modulation of mineralocorticoid receptor and thyroid hormone receptor activity in the heart (72). Moreover, transgenic mice expressing human SRA in the mammary glands and uterus of females, as well as in the urogenital system of males, exhibit reduced fertility. Furthermore, mature virgin SRA mammary gland transgenic mice exhibit abnormal mammary gland development (72). These results are consistent with a regulatory role for SRA with PR and ER.

In addition, expression of SRA has been implicated in mammary carcinogenesis. For example, crossing SRA transgenic mice with MMTV-ras mice, a model highly susceptible to the development of mammary tumors, reduces the incidence of mammary neoplasia (72). In contrast, knockdown of SRA in MDA-MB-231 human mammary cancer cells, a model of invasive breast cancer with elevated expression of SRA, leads to reduced invasiveness (73). Why reduced expression of SRA in one system and overexpression in another would both reduce aspects of cancer development and progression remains to be determined but may be related to the differential effects of SRA during organ development vs in established cancers.

Surprisingly, although SRA was initially characterized as noncoding (53), several SRA isoforms have now been found to encode a protein referred to as SRAP, making the SRA gene a unique host of both lncRNAs and protein-coding mRNAs (74). Although the exact roles of SRAP remain to be fully elucidated, the available data implicate SRA in regulating the activities of multiple NRs in its RNA forms, leading to pleiotropic effects in normal endocrine functions, as well as disease states of metabolic, cardiac, and reproductive tissues.

The GAS5 lncRNA functions as a “riborepressor” (ie, an RNA-based interactor and repressor) for the GR and possibly other NRs. GAS5 binds to the DNA binding domain of the GR, preventing it from binding to its regulatory sites across the genome (58) (Figure 4, panel 4). Like the GR, GAS5 has effects that are metabolic and others that are immunological. GAS5 accumulates in growth-arrested cells, which can be triggered by serum starvation or inhibition of protein translation. In cell-based studies, overexpression of GAS5 suppresses ligand-induced up-regulation of glucose 6-phosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, rate-limiting enzymes in glucose metabolism (58). The GAS5 gene is located in the disease susceptibility locus in the BSXB mouse strain, a model of glomerulonephritis observed in systemic lupus erythematosus, possibly affecting the pathogenesis of the autoimmune disease by suppressing the antiapoptotic functions of glucocorticoids (75). GAS5 has also been implicated in breast cancer. It is expressed at reduced levels in tumors compared with those in unaffected breast epithelial tissues, and reduced expression of GAS5 is associated with a poorer prognosis, consistent with its role in promoting apoptosis (76).

Whereas the functions of SRA and GAS5 have been linked to many NRs, other lncRNAs are involved in specific NR signaling pathways. For example, Takayama et al (77, 78) have recently uncovered novel functions of CTBP1-AS, an androgen-responsive lncRNA associated with the AR signaling pathway. CTBP1-AS runs antisense to the gene-encoding C-terminal binding protein 1 (CTBP1), which is a corepressor of AR. Consistent with its gene location, CTBP1-AS directly represses the expression of CTBP1 by recruiting polypyrimidine tract–binding protein–associated splicing factor (an RNA-binding transcriptional repressor) and histone deacetylases, which in turn promotes AR transcriptional activity (77). Nevertheless, the functional roles of CTBP1-AS extend beyond the regulation of CTBP1 in prostate cancer cell models to repression of an additional set of endogenous tumor suppressor genes and promotion of both hormone-dependent and castration-resistant tumor growth (77).

Furthermore, transcripts originating near the promoter of the PR gene (called promoter-associated RNAs) (Figure 2), some of which fit the definition of lncRNAs, may modulate the expression of PR and, hence, affect PR functions (79, 80). These PR gene–associated lncRNAs may act to modulate transcriptional responses to the steroid hormone progesterone and affect downstream cell proliferation and differentiation responses in target tissues. Transcriptome profiling in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells using global nuclear run-on sequencing (a method for mapping transcriptionally active RNA polymerases across the genome) identified a large number of lncRNA-like transcripts (81). About a quarter of these transcripts are estrogen-regulated, and many of the estrogen–up-regulated lncRNAs have ERα binding sites within their proximal promoter regions, suggesting direct involvement of ERα in the regulation of their expression (81). Despite the initial characterization, the full implications of these PR- and ERα-associated lncRNAs in the endocrine system have yet to be fully realized.

LncRNAs involved in mammary development

In addition to SRA, other lncRNAs that have been implicated in mammary development, an endocrine-related developmental program. For example, Pinc (pregnancy-induced noncoding RNA) was originally identified as a persistently up-regulated gene in rat mammary gland for at least 28 days after pregnancy or after 21 days of treatment with estrogen and progesterone (82). It was also found to be markedly induced after acute treatment with estrogen and progesterone or progesterone alone (83). Indeed, Pinc is an lncRNA whose expression is coordinately regulated during alveolar development in the mouse mammary gland, functioning to prevent alveolar differentiation before parturition (84). Molecularly, Pinc has been shown to interact with the PRC2 complex, suggesting a role for Pinc in cell fate decisions in alveologenesis through PRC2-associated epigenetic regulation (84), possibly in a manner similar to the mechanisms of HOTAIR, as described above (Figure 4, panel 2).

Pinc is conserved across mammals and is alternatively spliced into 2 variants, mPINC1.0 and mPINC1.6. In HC11 cells, a clonal mammary epithelial cell line derived from a midpregnant mouse mammary gland, the Pinc splice variants localize to distinct foci in either the cytoplasm or the nucleus in a cell cycle- and transcript-specific manner. Whereas knockdown of mPINC1.0 promotes apoptotic cell death, knockdown of mPINC1.6 leads to premature entry into the S phase (83). Therefore, the 2 Pinc splice variants play distinct roles in controlling cell survival and cell cycle progression in a specific population of mammary epithelial cells.

Zfas1 (zinc finger antisense 1), a transcript that intronically hosts 3 C/D box small nucleolar RNAs (Snord12, Snord12b, and Snord12c), is another lncRNA involved in mammary gland development. Based on results from microarray expression profiling of mammary epithelial cells isolated from pregnant, lactating, and involuting mice, Zfas1 was selected for further characterization as a candidate that plays a role in mammary gland development (85). Its expression is dynamically regulated across the developmental time course, in a manner similar to the coordinated expression of Pinc. Because knockdown of Zfas1 in HC11 cells promotes cell proliferation and differentiation (85), it probably acts as a repressor during mammary gland development in a manner similar to the role of Pinc in inhibiting alveolar differentiation. The syntenic ortholog of Zfas1 in humans has been identified. Consistent with the results from mouse, human ZFAS1 is highly expressed in mammary tissue. Moreover, it is expressed at reduced levels in invasive ductal carcinoma compared with those in normal breast tissues, suggesting a role of ZFAS1 as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer (85).

LncRNAs involved in adipogenesis

Parallel to the discovery of Zfas1 as a regulator of alveolar development and epithelial cell differentiation through expression profiling, lncRNAs expressed during mouse adipogenesis have been identified using transcriptome profiling in primary brown and white adipocytes, preadipocytes, and cultured adipocytes (33). Candidate adipogenic lncRNAs that were selected for further study are tightly regulated during adipogenesis and are probably controlled by known adipogenetic transcription factors, such as PPARγ and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α. RNA interference (RNAi)–mediated loss-of-function screening, coupled with a unique application of the information-theoretic metric in scoring the resultant phenotypes, has identified 10 lncRNAs that are required for the differentiation of primary white preadipocytes, including lncRNAs regulated in adipogenesis, lnc-RAP-1 and lnc-RAP-2 (33). Microarray expression analyses upon depletion of these and other functionally related lncRNAs revealed a corresponding dysregulation of adipogenic gene expression programs. Thus, adipogenesis-related lncRNAs, whose expression is coordinately regulated by classic adipogenic transcription factors, in turn regulate adipogenic transcription programs to play a previously underappreciated role in adipogenesis.

The Expanding Realm of LncRNAs in Molecular Endocrinology

Our emerging understanding of lncRNAs has dramatically changed our view on the depth and complexity of the mammalian genome and transcriptome. In contrast to the fast-growing number of lncRNAs being identified, efforts are lagging in the determination of their molecular and biological functions, partly due to our inability to interpret the “language” used by this new class of molecules. Unlike microRNAs, lncRNAs do not share a common mechanism of action, and primary sequences offer few opportunities to infer molecular details about their mode of action. Moreover, most lncRNAs are expressed at low steady-state levels, making characterization technically difficult. Nevertheless, sufficient evidence supports the assertion that lncRNAs, in collaboration with proteins, function as integral components of a wide array of biological processes, such as reproductive and metabolic pathways of the endocrine system. We expect an even greater number of lncRNAs to serve important functions in the endocrine system, and efforts are underway to understand the lncRNA piece of the endocrinology puzzle. Future studies will (1) identify more endocrine-related lncRNAs and (2) characterize their molecular mechanisms of action.

Identification and biological functions of endocrine-related lncRNAs

Further understanding of the roles of lncRNAs in endocrinology will require the identification and characterization of more lncRNAs associated with endocrine functions. Gene-specific molecular biology assays and high throughput genomic approaches have been used to facilitate the exploration of lncRNAs. As in the case of adipogenic lncRNAs described above, researchers have tapped into the temporally and spatially regulated nature of lncRNAs to select candidates that are probably functional in specific biological pathways (33). Subsequent loss-of-function experiments using RNAi-mediated knockdown in cell lines (or better yet, through the generation of knockout animal models) will validate associations between lncRNAs and corresponding functional pathways and physiological outcome. Gain-of-function experiments, as in the case of transgenic zebrafish and mice that express SRA, can be useful as well (72). Carefully designed experiments performed under the right biological conditions will allow the association of specific lncRNAs with key endocrine functions, which can be explored in more detail in mechanistic experiments.

Characterization of the molecular mechanisms of action of endocrine-related LncRNAs

To investigate the molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs, several strategies serve as a good starting point of investigation. The subcellular localization of lncRNAs, which can be detected by RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, provides clues to their biological functions (86–92). Nucleus-localized lncRNAs, especially those that are associated with chromatin, are more likely to be involved in transcriptional regulation or epigenetic control, whereas cytoplasmic lncRNAs may mediate aspects of posttranscriptional regulation. For chromatin-associated lncRNAs, newly developed methods, such as chromatin isolation by RNA purification (93) or capture hybridization analysis of RNA targets (94), can be used to map the interaction of specific lncRNAs along the genome and to identify their direct genomic targets. Because most characterized lncRNAs mediate their functions by interacting with proteins, another common approach for determining the molecular function of a lncRNA is to identify its protein partners, through either RIP-based methods or RNA pulldown followed by identification of lncRNA-bound proteins using mass spectrometry. Known functions of protein interaction partners provide insights into the functions mediated by the lncRNAs.

Therapeutic potential of endocrine-related lncRNAs

Ultimately, the field should explore the utility of endocrine-associated lncRNAs in clinical applications to facilitate the treatment of diseases, such as hormone-regulated cancers. lncRNAs have been exploited as diagnostic and prognostic tools in cancers. The PCA3 lncRNA is markedly elevated in urine samples from patients with prostate cancer, which has been developed into a clinical test for detecting prostate cancer (95). The expression of HOTAIR predicts poorer survival and poorer metastasis-free survival, potentially serving as a prognostic marker (96). Moreover, owing to their tissue-specific nature, the differential expression of lncRNAs can facilitate the classification of disease samples into distinct subtypes, which may serve as better prognostic indicators.

Compared with the promises of lncRNA-based markers, lncRNA-based therapies face many challenges. Nonetheless, experimental therapeutic agents targeting lncRNAs in disease models are being tested. Antisense oligonucleotide–based knockdown of MALAT1 in human non–small cell lung cancer EBC-1 cells mitigates tumor metastasis to the lung in mouse xenograph models (97). Nevertheless, the feasibility of using antisense oligonucleotides in clinical therapy is still undetermined, and the safety and efficacy of using other forms of knockdown strategies, including RNAi, are still being assessed in clinical trials. A very limited number of lncRNAs have been characterized to a sufficient extent to serve as reliable targets for therapeutic interventions in diseases (17, 97–99). However, because of the great potential of lncRNA-based therapies, their development calls for continued research. As a start, a more comprehensive understanding of the normal physiological effects of candidate lncRNAs in whole animals is required. Such efforts may lead to a time when targeting lncRNAs for the treatment of endocrine-related diseases becomes a reality.

Summary and Conclusions

The expanding world of lncRNAs represents an added layer of complexity in molecular biology. Examples of well-characterized, biologically important lncRNAs clearly exist, although there are still many gaps in our understanding of lncRNAs in terms of their molecular and biological functions and to what extent they are required for life. Nevertheless, this new class of RNA molecules presents an exciting opportunity that deserves further investigation into both their physiological roles and molecular mechanisms of action.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Kraus Laboratory for critical review of this article.

The lncRNA-related work in the Kraus Laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AR

- androgen receptor

- ceRNA

- competing endogenous RNA

- CTBP1

- C-terminal binding protein 1

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- GRE

- glucocorticoid response element

- lincRNA

- long intergenic ncRNAs

- lncRNA

- long noncoding RNA

- mRNA

- messenger RNA

- ncRNA

- noncoding RNA

- ncRNA-a

- noncoding RNA-activating

- NR

- nuclear receptor

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ

- PR

- progesterone receptor

- PRC2

- polycomb repressive complex 2

- RIP

- RNA immunoprecipitation

- RNAi

- RNA, interference

- rRNA

- ribosomal RNA

- SMD

- STAU1-mediated mRNA decay

- snRNA

- small nuclear RNA

- tRNA

- transfer RNA

- XCI

- X chromosome inactivation.

References

- 1. Crick F. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature. 1970;227:561–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okazaki Y, Furuno M, Kasukawa T, et al. Analysis of the mouse transcriptome based on functional annotation of 60,770 full-length cDNAs. Nature. 2002;420:563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489:101–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kapranov P, Cheng J, Dike S, et al. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science. 2007;316:1484–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brannan CI, Dees EC, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM. The product of the H19 gene may function as an RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:28–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brockdorff N, Ashworth A, Kay GF, et al. Conservation of position and exclusive expression of mouse Xist from the inactive X chromosome. Nature. 1991;351:329–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 2005;309:1559–1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell. 2013;152:1298–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Novikova IV, Hennelly SP, Sanbonmatsu KY. Sizing up long non-coding RNAs: do lncRNAs have secondary and tertiary structure? Bioarchitecture. 2012;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bánfai B, Jia H, Khatun J, et al. Long noncoding RNAs are rarely translated in two human cell lines. Genome Res. 2012;22:1646–1657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:145–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell. 2011;147:789–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ma L, Bajic VB, Zhang Z. On the classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol. 2013;10(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1494–1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prensner JR, Chinnaiyan AM. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:391–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22:1775–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chew GL, Pauli A, Rinn JL, Regev A, Schier AF, Valen E. Ribosome profiling reveals resemblance between long non-coding RNAs and 5′ leaders of coding RNAs. Development. 2013;140:2828–2834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guttman M, Garber M, Levin JZ, et al. Ab initio reconstruction of cell type-specific transcriptomes in mouse reveals the conserved multi-exonic structure of lincRNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:503–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, et al. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1915–1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sigova AA, Mullen AC, Molinie B, et al. Divergent transcription of long noncoding RNA/mRNA gene pairs in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2876–2881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hon GC, Hawkins RD, Ren B. Predictive chromatin signatures in the mammalian genome. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R195–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ulitsky I, Shkumatava A, Jan CH, Sive H, Bartel DP. Conserved function of lincRNAs in vertebrate embryonic development despite rapid sequence evolution. Cell. 2011;147:1537–1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ørom UA, Derrien T, Beringer M, et al. Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells. Cell. 2010;143:46–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ponjavic J, Ponting CP, Lunter G. Functionality or transcriptional noise? Evidence for selection within long noncoding RNAs. Genome Res. 2007;17:556–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marques AC, Ponting CP. Catalogues of mammalian long noncoding RNAs: modest conservation and incompleteness. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Klattenhoff CA, Scheuermann JC, Surface LE, et al. Braveheart, a long noncoding RNA required for cardiovascular lineage commitment. Cell. 2013;152:570–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kretz M, Siprashvili Z, Chu C, et al. Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature. 2013;493:231–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun L, Goff LA, Trapnell C, et al. Long noncoding RNAs regulate adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3387–3392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schonrock N, Harvey RP, Mattick JS. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and pathophysiology. Circ Res. 2012;111:1349–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477:295–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Katayama S, Tomaru Y, Kasukawa T, et al. Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science. 2005;309:1564–1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mercer TR, Wilhelm D, Dinger ME, et al. Expression of distinct RNAs from 3′ untranslated regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2393–2403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kurokawa R. Promoter-associated long noncoding RNAs repress transcription through a RNA binding protein TLS. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;722:196–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Penny GD, Kay GF, Sheardown SA, Rastan S, Brockdorff N. Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature. 1996;379:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marahrens Y, Panning B, Dausman J, Strauss W, Jaenisch R. Xist-deficient mice are defective in dosage compensation but not spermatogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:156–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wutz A, Jaenisch R. A shift from reversible to irreversible X inactivation is triggered during ES cell differentiation. Mol Cell. 2000;5:695–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wutz A, Rasmussen TP, Jaenisch R. Chromosomal silencing and localization are mediated by different domains of Xist RNA. Nat Genet. 2002;30:167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song JJ, Lee JT. Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science. 2008;322:750–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jeon Y, Lee JT. YY1 tethers Xist RNA to the inactive X nucleation center. Cell. 2011;146:119–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kotake Y, Nakagawa T, Kitagawa K, et al. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is required for the PRC2 recruitment to and silencing of p15(INK4B) tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2011;30:1956–1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang KC, Yang YW, Liu B, et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lai F, Orom UA, Cesaroni M, et al. Activating RNAs associate with Mediator to enhance chromatin architecture and transcription. Nature. 2013;494:497–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129:1311–1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Khalil AM, Guttman M, Huarte M, et al. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11667–11672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhao J, Ohsumi TK, Kung JT, et al. Genome-wide identification of polycomb-associated RNAs by RIP-seq. Mol Cell. 2010;40:939–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Colley SM, Leedman PJ. Steroid receptor RNA activator—a nuclear receptor coregulator with multiple partners: insights and challenges. Biochimie. 2011;93:1966–1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lanz RB, McKenna NJ, Onate SA, et al. A steroid receptor coactivator, SRA, functions as an RNA and is present in an SRC-1 complex. Cell. 1999;97:17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hatchell EC, Colley SM, Beveridge DJ, et al. SLIRP, a small SRA binding protein, is a nuclear receptor corepressor. Mol Cell. 2006;22:657–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shi Y, Downes M, Xie W, et al. Sharp, an inducible cofactor that integrates nuclear receptor repression and activation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1140–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Caretti G, Schiltz RL, Dilworth FJ, et al. The RNA helicases p68/p72 and the noncoding RNA SRA are coregulators of MyoD and skeletal muscle differentiation. Dev Cell. 2006;11:547–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hube F, Guo J, Chooniedass-Kothari S, et al. Alternative splicing of the first intron of the steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA) participates in the generation of coding and noncoding RNA isoforms in breast cancer cell lines. DNA Cell Biol. 2006;25:418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kino T, Hurt DE, Ichijo T, Nader N, Chrousos GP. Noncoding RNA gas5 is a growth arrest- and starvation-associated repressor of the glucocorticoid receptor. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Poliseno L, Salmena L, Zhang J, Carver B, Haveman WJ, Pandolfi PP. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. 2010;465:1033–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, et al. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell. 2011;147:358–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang Y, Xu Z, Jiang J, et al. Endogenous miRNA sponge lincRNA-RoR regulates Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 in human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Dev Cell. 2013;25:69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Loewer S, Cabili MN, Guttman M, et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1113–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Johnsson P, Ackley A, Vidarsdottir L, et al. A pseudogene long-noncoding-RNA network regulates PTEN transcription and translation in human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:440–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gong C, Maquat LE. lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3′ UTRs via Alu elements. Nature. 2011;470:284–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Huo JS, Zambidis ET. Pivots of pluripotency: the roles of non-coding RNA in regulating embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:2385–2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sana J, Faltejskova P, Svoboda M, Slaby O. Novel classes of non-coding RNAs and cancer. J Transl Med. 2012;10:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Spizzo R, Almeida MI, Colombatti A, Calin GA. Long non-coding RNAs and cancer: a new frontier of translational research? Oncogene. 2012;31:4577–4587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yan B, Wang Z. Long noncoding RNA: its physiological and pathological roles. DNA Cell Biol. 2012;31(suppl 1):S34–S41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Xu B, Gerin I, Miao H, et al. Multiple roles for the non-coding RNA SRA in regulation of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Xu B, Yang WH, Gerin I, Hu CD, Hammer GD, Koenig RJ. Dax-1 and steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA) function as transcriptional coactivators for steroidogenic factor 1 in steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1719–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kelly VR, Xu B, Kuick R, Koenig RJ, Hammer GD. Dax1 up-regulates Oct4 expression in mouse embryonic stem cells via LRH-1 and SRA. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:2281–2291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lanz RB, Chua SS, Barron N, Soder BM, DeMayo F, O'Malley BW. Steroid receptor RNA activator stimulates proliferation as well as apoptosis in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7163–7176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Foulds CE, Tsimelzon A, Long W, et al. Research resource: expression profiling reveals unexpected targets and functions of the human steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA) gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1090–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chooniedass-Kothari S, Emberley E, Hamedani MK, et al. The steroid receptor RNA activator is the first functional RNA encoding a protein. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Haywood ME, Rose SJ, Horswell S, et al. Overlapping BXSB congenic intervals, in combination with microarray gene expression, reveal novel lupus candidate genes. Genes Immun. 2006;7:250–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Pickard MR, Hedge VL, Farzaneh F, Williams GT. GAS5, a non-protein-coding RNA, controls apoptosis and is downregulated in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:195–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Takayama K, Horie-Inoue K, Katayama S, et al. Androgen-responsive long noncoding RNA CTBP1-AS promotes prostate cancer. EMBO J. 2013;32:1665–1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Takayama K, Tsutsumi S, Katayama S, et al. Integration of cap analysis of gene expression and chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis on array reveals genome-wide androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2011;30:619–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Schwartz JC, Younger ST, Nguyen NB, et al. Antisense transcripts are targets for activating small RNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:842–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Janowski BA, Younger ST, Hardy DB, Ram R, Huffman KE, Corey DR. Activating gene expression in mammalian cells with promoter-targeted duplex RNAs. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:166–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hah N, Danko CG, Core L, et al. A rapid, extensive, and transient transcriptional response to estrogen signaling in breast cancer cells. Cell. 2011;145:622–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ginger MR, Gonzalez-Rimbau MF, Gay JP, Rosen JM. Persistent changes in gene expression induced by estrogen and progesterone in the rat mammary gland. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1993–2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ginger MR, Shore AN, Contreras A, et al. A noncoding RNA is a potential marker of cell fate during mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5781–5786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Shore AN, Kabotyanski EB, Roarty K, et al. Pregnancy-induced noncoding RNA (PINC) associates with polycomb repressive complex 2 and regulates mammary epithelial differentiation. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Askarian-Amiri ME, Crawford J, French JD, et al. SNORD-host RNA Zfas1 is a regulator of mammary development and a potential marker for breast cancer. RNA. 2011;17:878–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Redrup L, Branco MR, Perdeaux ER, et al. The long noncoding RNA Kcnq1ot1 organises a lineage-specific nuclear domain for epigenetic gene silencing. Development. 2009;136:525–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Murakami K, Oshimura M, Kugoh H. Suggestive evidence for chromosomal localization of non-coding RNA from imprinted LIT1. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:926–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Nagano T, Mitchell JA, Sanz LA, et al. The air noncoding RNA epigenetically silences transcription by targeting G9a to chromatin. Science. 2008;322:1717–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Pandey RR, Mondal T, Mohammad F, et al. Kcnq1ot1 antisense noncoding RNA mediates lineage-specific transcriptional silencing through chromatin-level regulation. Mol Cell. 2008;32:232–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Murakami K, Ohhira T, Oshiro E, Qi D, Oshimura M, Kugoh H. Identification of the chromatin regions coated by non-coding Xist RNA. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2009;125:19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Duthie SM, Nesterova TB, Formstone EJ, et al. Xist RNA exhibits a banded localization on the inactive X chromosome and is excluded from autosomal material in cis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Clemson CM, Chow JC, Brown CJ, Lawrence JB. Stabilization and localization of Xist RNA are controlled by separate mechanisms and are not sufficient for X inactivation. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:13–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Chu C, Qu K, Zhong FL, Artandi SE, Chang HY. Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Mol Cell. 2011;44:667–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Simon MD, Wang CI, Kharchenko PV, et al. The genomic binding sites of a noncoding RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20497–20502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lee GL, Dobi A, Srivastava S. Prostate cancer: diagnostic performance of the PCA3 urine test. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8:123–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Eissmann M, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1180–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Leung A, Trac C, Jin W, et al. Novel long non-coding RNAs are regulated by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells [published online ahead of print May 22, 2013]. Circ Res. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sánchez Y, Huarte M. Long non-coding RNAs: challenges for diagnosis and therapies. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2013;23:15–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]