Abstract

Purpose

To test whether reducing radiation dose to uninvolved bladder while maintaining dose to the tumor would reduce side effects without impairing local control in the treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Methods and Materials

In this phase III multicenter trial, 219 patients were randomized to standard whole-bladder radiation therapy (sRT) or reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy (RHDVRT) that aimed to deliver full radiation dose to the tumor and 80% of maximum dose to the uninvolved bladder. Participants were also randomly assigned to receive radiation therapy alone or radiation therapy plus chemotherapy in a partial 2 × 2 factorial design. The primary endpoints for the radiation therapy volume comparison were late toxicity and time to locoregional recurrence (with a noninferiority margin of 10% at 2 years).

Results

Overall incidence of late toxicity was less than predicted, with a cumulative 2-year Radiation Therapy Oncology Group grade 3/4 toxicity rate of 13% (95% confidence interval 8%, 20%) and no statistically significant differences between groups. The difference in 2-year locoregional recurrence free rate (RHDVRT − sRT) was 6.4% (95% confidence interval −7.3%, 16.8%) under an intention to treat analysis and 2.6% (−12.8%, 14.6%) in the “per-protocol” population.

Conclusions

In this study RHDVRT did not result in a statistically significant reduction in late side effects compared with sRT, and noninferiority of locoregional control could not be concluded formally. However, overall low rates of clinically significant toxicity combined with low rates of invasive bladder cancer relapse confirm that (chemo)radiation therapy is a valid option for the treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Summary.

This was a phase III trial assessing whether reducing radiation dose to uninvolved bladder reduces toxicity without impairing local control; 219 patients were randomized. No significant differences in toxicity were seen between standard and reduced high-dose volume RT groups. Rates of late toxicity were lower than anticipated. Noninferiority of local control was not formally proven. Radiation therapy can be an effective alternative to cystectomy in patients with bladder cancer; further study using image-guided treatment with or without dose escalation is warranted.

Introduction

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer remains a major cause of cancer death worldwide (1), with 5-year survival rates of <50% 2, 3. Although cystectomy is frequently seen as standard treatment (4), bladder-sparing protocols utilizing radical radiation therapy are used as an alternative for those patients unsuitable for or unwilling to undergo radical surgery. Historically, drawbacks of this approach were twofold: (i) the rate of incomplete response or local recurrence (up to 50%) (5) with the need for subsequent salvage cystectomy; and (ii) the risk of late toxicity in the bladder, rectum, or bowel (severe toxicity rates of 8%-10%, 3%-4%, and 1%-2% reported for bladder, rectum, and bowel, respectively (6)).

When radiation therapy is used, difficulties in tumor localization, in ensuring accuracy of treatment delivery, and the propensity for bladder cancer to be multifocal have meant that the whole bladder is conventionally taken as the target volume even if the tumor appears localized. However, brachytherapy data (7) and a small randomized trial (8) have suggested that targeting treatment to the tumor may give equivalent local control, and retrospective data suggest that reducing normal bladder tissue included in the high-dose volume may reduce the risk of toxicity (9).

A single-center pilot study of this approach resulted in lower rates of toxicity (10); the radiation therapy volume comparison in the BC2001 (CRUK/01/004) trial was designed to assess whether this was reproducible across multiple centers without a detrimental effect on locoregional disease control. On the basis of results of an earlier phase II study demonstrating safety of chemo-radiation therapy (11), we also investigated whether outcomes can be improved by the addition of chemotherapy to radiation therapy (results reported separately (12)).

Methods and Materials

Study design

BC2001 was a nonblinded phase III trial, with a partial 2 × 2 factorial design, conducted at 45 United Kingdom (UK) centers. Patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer providing written informed consent were randomized (in a 1:1 ratio) to (i) standard whole-bladder radiation therapy (sRT) or reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy (RHDVRT) utilizing a tumor boost and (ii) radiation therapy with or without synchronous chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil [5FU] and mitomycin C [MMC]). Recruitment to the double randomization was encouraged but optional according to patient eligibility and preference.

Independent randomization was via telephone to the Institute of Cancer Research Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit (ICR-CTSU). Computer-generated random permuted blocks were used, stratifying by treating center, planned neoadjuvant chemotherapy use, and entry to one or both randomizations.

Patient eligibility and selection

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with histologically confirmed stage T2-T4aN0M0 bladder cancer (adenocarcinoma or transitional or squamous cell carcinoma). Main inclusion criteria were as follows: World Health Organization performance status grade 0-2, leucocytes >4.0 × 109/L, platelets >100 × 109/L, Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) >25 mL/min, and serum bilirubin, Alanine transaminase (ALT), or Aspartate Transaminase (AST) <1.5 × upper limit of normal. Platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy was permitted but not mandatory. Main exclusions were other malignancy in the last 2 years, previous pelvic radiation therapy, bilateral hip replacements likely to interfere with protocol treatment, pregnancy, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Patients with multiple tumors at diagnosis were ineligible for the radiation therapy volume randomization but could enter the chemo-radiation therapy randomization; patients unsuitable for chemotherapy could enter the radiation therapy volume randomization.

Treatment

Two radiation therapy dose/fractionation schedules in standard use in the UK were permitted: centers opted at study outset to use either 55 Gy/20 fractions over 4 weeks or 64 Gy/32 fractions over 6.5 weeks for all participants. Patients allocated to concomitant chemotherapy received 5FU (500 mg/m2/24 hours continuous infusion during fractions 1-5 and 16-20 of radiation therapy [10 days in total]) and MMC (12 mg/m2 intravenous bolus dose on day 1).

Dose modifications for chemotherapy and radiation therapy were permitted. In brief, the protocol recommended reducing or omitting chemotherapy before interrupting radiation therapy to minimize compromising delivery of “core” treatment.

Radiation therapy was CT planned with tumor, clinical, and planning target volumes defined on 4 to 5 mm thick CT slices taken at 4 to 5 mm intervals. Patients were CT planned with an empty bladder and a rectum empty of flatus and feces. Target outlining was performed according to local practice.

For patients allocated sRT (control) the planning target volume (PTV) was the outer bladder wall plus the extravesical extent of tumor with a 1.5 cm margin. An anterior and 2 lateral fields were used to encompass the PTV in the 95% isodose. For RHDVRT patients, 2 PTVs were defined: PTV1 as for the sRT group, and PTV2 as gross tumor volume (ie, tumor seen on MRI/CT with guidance of surgical bladder map) plus a 1.5-cm margin. Three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy was used; RHDVRT could be delivered as a concomitant boost. The aim of the RHDVRT treatment was to deliver 100% (±5%) of the reference dose to PTV2 and 80% (±5%) of the reference dose to PTV1 using 3 or 4 coplanar fields (Fig. e1, available online). Treatment plans for the first patient treated with sRT and the first 2 patients receiving RHDVRT at each site were centrally reviewed, with structured feedback to the local investigator. In both groups, nontarget normal tissues were excluded at the treating physician’s discretion. Patients were set up according to bony landmarks. Soft tissue matching was not used.

Trial assessments

At baseline all patients underwent physical examination, hematologic, renal, and biochemical profile examination, bladder capacity assessment, CT scan of abdomen and pelvis, chest x-ray or CT, and examination under anesthetic plus cystoscopic resection of tumor and biopsy. The TNM classification (1997) was used for staging (13).

Patients were seen weekly throughout treatment for toxicity assessment using National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) (14). Side effects were then assessed at 6, 9, and 12 months after randomization and annually thereafter using the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) (15) and Late Effects of Normal Tissue (Subjective, Objective, Management) (LENT/SOM) (16) scales. Bladder capacity was measured at 1 and 2 years by urodynamic examination, cystoscopy, or ultrasound (same technique used for individual patients).

Tumor control was assessed by physical examination, chest x-ray, and rigid or flexible cystoscopy at 6, 9, and 12 months after randomization and annually to 5 years. Biopsy of the tumor bed and normal bladder was mandated at 6 months and repeated if indicated at subsequent visits. Computed tomography scans of the abdomen and pelvis were performed 1 and 2 years after randomization and then as indicated.

Endpoints

Late radiation therapy related side effects (at 1 and 2 years) and local control were the principal endpoints of interest. Late toxicity was assessed by worst toxicity grade and change in bladder capacity. Locoregional recurrence–free (LRRF) survival was defined as time from randomization to first recurrence in pelvic nodes or bladder, censored at date of first metastasis (if ≥30 days before locoregional recurrence), second primary, or death or, for patients without an event, date last seen. Local recurrences included new non–muscle-invasive disease. Secondary endpoints included acute toxicity (worst grade during treatment), salvage cystectomy rate (time from randomization to cystectomy, censored at death), and overall survival.

Sample size

The sample size was based on demonstrating an improved toxicity profile in the RHDVRT group. Pilot data showed that modifying the volume of bladder irradiated with the full dose of radiation therapy reduced RTOG grade (G)3 or G4 bladder toxicity from 43% to 23% (10). Assuming 25% of patients would not be evaluable for toxicity at 1 year (eg, because of death), the trial set out to randomize 480 patients to detect a reduction from 40% to 25% in RTOG G3/4 toxicity (86% power, 5% 2-sided significance). The study also aimed to demonstrate that RHDVRT was at most 10% inferior to sRT in terms of 2-year LRRF rate (assuming a 2-year rate of 50% with sRT; 70% power, 1-sided α = 0.05). There was clinical consensus that this noninferiority margin would be acceptable if toxicity was significantly reduced.

Because of slow recruitment, the radiation therapy volume randomization closed early in September 2006. Retrospective recalculation of power showed that with 164 patients assessable for late toxicity at 1 year the study could detect a 20% difference (40% to 20%) in RTOG G3/4 toxicity with 80% power (5% 2-sided significance). Two hundred and nineteen randomized patients provided only 56% power to detect noninferiority with a margin of 10%.

Statistical analysis

Primary analyses are by intention to treat (ITT) for efficacy outcomes, including all randomized patients, and by treatment received for toxicity endpoints, including all patients who received any radiation therapy. The primary noninferiority analysis was also performed excluding patients who did not receive their allocated radiation therapy volume treatment or had major protocol violations (“per-protocol” population). Noninferiority was to be considered proven if conclusions drawn from the ITT and per-protocol analyses were consistent. All analyses were adjusted or stratified for randomized chemotherapy group (chemotherapy/no chemotherapy/not randomized).

Proportion of G3/4 toxicities was compared using the Mantel-Haenszel test and distribution of toxicity grades using the Van Elteren test. To avoid interpreting disease symptoms as treatment side effects, late toxicity data were treated as missing from 3 months before first recurrence, second primary, or bladder cancer death. To make some adjustment for multiple testing, a significance level of 1% was used for toxicity endpoints at individual timepoints, and accordingly 99% confidence intervals (CIs) are given. Where overall cumulative toxicity rates are presented, 95% CIs are given. Mean change in bladder capacity is calculated from an analysis of covariance model adjusting for baseline capacity and randomized chemotherapy group.

Time to event endpoints were analyzed by stratified log–rank test. Hazard ratios (hazard ratio <1 favoring RHDVRT) and absolute difference were calculated from the Cox model. The proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model, tested using Schoenfeld residuals, held for all endpoints except time to cystectomy. Hazard ratios adjusted for neoadjuvant chemotherapy, age, radiation therapy dose, stage, performance status, and tumor grade suggested robustness of the results (not shown).

The presence of an interaction between chemotherapy and radiation therapy volume was tested for survival and toxicity outcomes, but the tests had low power because only 121 patients were randomized to both comparisons. Sensitivity analyses (not shown) were conducted as reported previously (12) and gave similar results to the main analysis.

Time-to-event analyses were based on a database snapshot frozen on November 2, 2011. All other analyses were based on a database snapshot frozen on April 27, 2010. Analyses were conducted in STATA 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Research governance

The trial was sponsored by the University of Birmingham and conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice with appropriate ethical and regulatory approvals. Central data management was performed by ICR-CTSU and Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit (CRCTU), Birmingham. Central statistical monitoring and all analyses were conducted at ICR-CTSU. The Trial Management Group (See acknowledgements) was responsible for the day to day running of the trial. The trial was overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee. An Independent Data Monitoring Committee regularly reviewed emerging safety and efficacy data.

Results

Trial participants

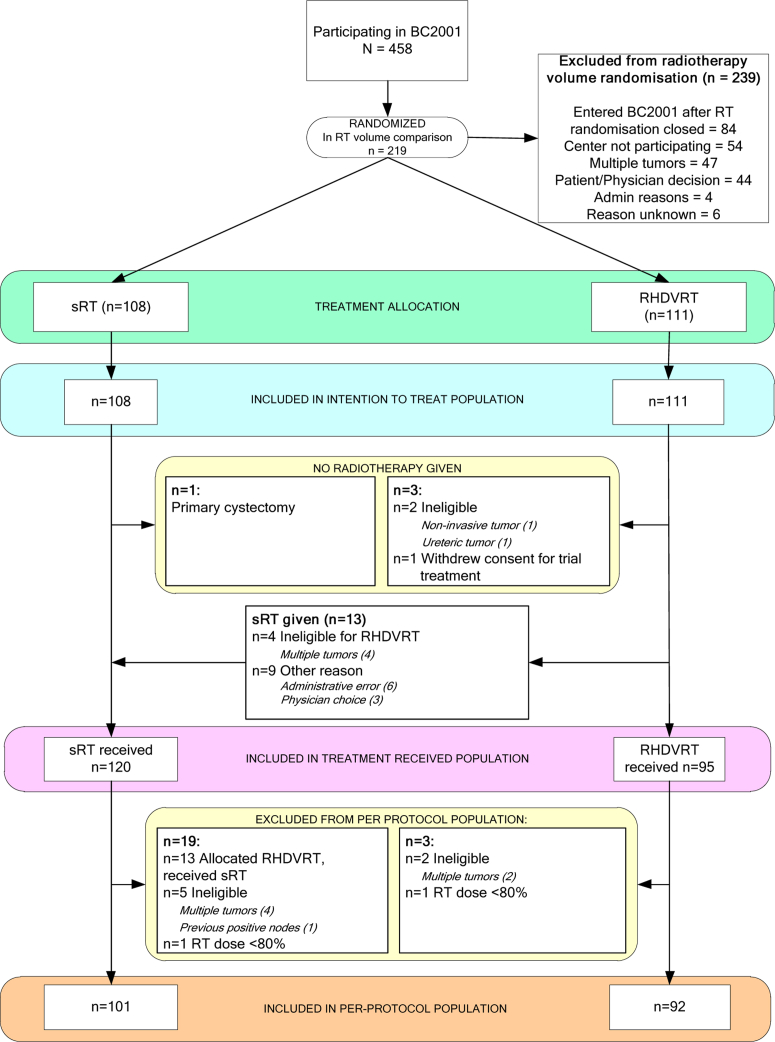

Between August 2001 and April 2008, 458 patients were recruited from 45 UK centers. Of these, 219 patients (108 sRT, 111 RHDVRT) from 28 UK centers entered the radiation therapy volume randomization, 360 patients entered the chemo-radiation therapy randomization, including 121 who entered both. Thirteen patients randomized to sRT versus RHDVRT were subsequently found to be ineligible, and 13 patients randomized to RHDVRT were treated with sRT (Fig. 1). Patient and tumor characteristics and treatment details are given in Table 1. Full-dose radiation therapy was received by more than 95% of patients. Median follow-up was 72.7 (interquartile range, 60.7 to 90.0) months.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow through the trial. RHDVRT = reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy; sRT = standard whole-bladder radiation therapy.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics at trial entry, and treatment details

| Variable | sRT |

RHDVRT |

Total |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 108 | 100.0 | 111 | 100.0 | 219 | 100.0 |

| Chemotherapy randomization | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | 31 | 28.7 | 33 | 29.7 | 64 | 29.2 |

| No chemotherapy | 32 | 29.6 | 25 | 22.5 | 57 | 26.0 |

| Elect no chemotherapy | 45 | 41.7 | 53 | 47.7 | 98 | 44.7 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 91 | 84.3 | 89 | 80.2 | 180 | 82.2 |

| Female | 17 | 15.7 | 22 | 19.8 | 39 | 17.8 |

| WHO performance Status | ||||||

| 0 | 57 | 52.8 | 56 | 50.5 | 113 | 51.6 |

| 1 | 42 | 38.9 | 45 | 40.5 | 87 | 39.7 |

| 2 | 9 | 8.3 | 10 | 9.0 | 19 | 8.7 |

| Age at randomization (y) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 75.0 (68.6, 79.9) | 73.1 (65.0, 78.1) | 74 (66.6, 79.0) | |||

| <60 | 10 | 9.3 | 13 | 11.7 | 23 | 10.5 |

| 60-69 | 23 | 21.3 | 28 | 25.2 | 51 | 23.3 |

| 70-79 | 49 | 45.4 | 50 | 45.0 | 99 | 45.2 |

| 80+ | 26 | 24.1 | 20 | 18.0 | 46 | 21.0 |

| Pathological stage, primary tumor | ||||||

| 2 | 94 | 87.0 | 90 | 81.1 | 184 | 84.0 |

| 3a | 5 | 4.6 | 7 | 6.3 | 12 | 5.5 |

| 3b | 5 | 4.6 | 11 | 9.9 | 16 | 7.3 |

| 4a | 3 | 2.8 | 2 | 1.8 | 5 | 2.3 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Grade, primary tumor | ||||||

| 2 | 19 | 17.6 | 17 | 15.3 | 36 | 16.4 |

| 3 | 85 | 78.7 | 93 | 83.8 | 178 | 81.3 |

| Unknown | 4 | 3.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 5 | 2.3 |

| Histologic type | ||||||

| TCC | 106 | 98.1 | 109 | 98.2 | 215 | 98.2 |

| SCC | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.5 |

| TCC and SCC | 1 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Multiple tumors | ||||||

| Yes∗ | 5 | 4.6 | 4 | 3.6 | 9 | 4.1 |

| If yes, no. of tumors | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (3, 3) | 2.5 (2, 3) | 3 (3, 3) | |||

| Number unknown | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| No | 102 | 94.4 | 106 | 95.5 | 208 | 95.0 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Tumor resection | ||||||

| Not resected | 3 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.9 | 4 | 1.8 |

| Biopsy | 7 | 6.5 | 9 | 8.1 | 16 | 7.3 |

| Complete resection | 56 | 51.9 | 63 | 56.8 | 119 | 54.3 |

| Incomplete resection | 39 | 36.1 | 36 | 32.4 | 75 | 34.2 |

| Resected (extent unknown) | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Unknown | 2 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 3 | 1.4 |

| Residual mass after resection | ||||||

| Yes | 38 | 35.2 | 25 | 22.5 | 63 | 28.8 |

| No | 65 | 60.2 | 79 | 71.2 | 144 | 65.8 |

| Unknown | 5 | 4.6 | 7 | 6.3 | 12 | 5.5 |

| Tumor size (longest dimension, mm) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 38 (20, 50) | 30 (20, 40) | 30 (20, 50) | |||

| Unknown | 33 | 32 | 65 | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy planned | ||||||

| Yes | 26 | 24.1 | 25 | 22.5 | 51 | 23.3 |

| No | 82 | 75.9 | 86 | 77.5 | 168 | 76.7 |

| Planned radiation therapy schedule | ||||||

| 55 Gy/20 fx | 43 | 39.8 | 35 | 31.5 | 78 | 35.6 |

| 64 Gy/32 fx | 64 | 59.3 | 75 | 67.6 | 139 | 63.5 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Radiation therapy dose received | ||||||

| Full dose | 105 | 97.2 | 106† | 95.5 | 211 | 96.3 |

| 80%-<100% | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.9 |

| <80% | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.9 |

| None | 1 | 0.9 | 3 | 2.7 | 4 | 1.8 |

| Radiation therapy delays | ||||||

| No delay ≥7 d | 106 | 98.1 | 107 | 96.4 | 213 | 97.3 |

| Delay ≥7 d | 2 | 1.9 | 4 | 3.6 | 6 | 2.7 |

Abbreviations: fx = fraction; IQR = interquartile range; RHDVRT = reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; sRT = standard whole-bladder radiation therapy; TCC = transitional cell carcinoma; WHO = World Health Organization.

All ineligible for radiation therapy randomization except 1 patient in the sRT group with all tumors in same location.

Includes 13 patients randomized to RHDVRT who received sRT.

Acute toxicity

In general, treatment was well tolerated, with G3/4 acute toxicity seen in 49 of 215 patients (23%) and no significant difference between radiation therapy volume groups (Table 2). The most common on-treatment toxicity was urinary related (G3/4 frequency/nocturia: 32 patients; G3/4 dysuria: 12 patients). The most frequent gastrointestinal toxicity was diarrhea (6 patients).

Table 2.

Worst grade of on-treatment CTC toxicity

| Acute toxicity | Group | Worst CTC grade |

P∗ | OR for G3/4† | 99% CI | P‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| Any toxicity | sRT | 120 | 4 (3.3) | 31 (25.8) | 55 (45.8) | 26 (21.7) | 4 (3.3) | .73 | 0.79 | 0.33, 1.87 | .48 |

| RHDVRT | 95 | 4 (4.2) | 23 (24.2) | 49 (51.6) | 17 (17.9) | 2 (2.1) | |||||

| Genitourinary | sRT | 117 | 23 (19.7) | 41 (35.0) | 33 (28.2) | 17 (14.5) | 3 (2.6) | .57 | 1.00 | 0.39, 2.60 | .99 |

| RHDVRT | 94 | 18 (19.1) | 30 (31.9) | 31 (33.0) | 14 (14.9) | 1 (1.1) | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | sRT | 117 | 25 (21.4) | 59 (50.4) | 27 (23.1) | 6 (5.1) | 0 | .85 | 0.38 | 0.04, 3.26 | .23 |

| RHDVRT | 94 | 25 (26.6) | 37 (39.4) | 30 (31.9) | 2 (2.1) | 0 | |||||

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; CTC = Common Toxicity Criteria; G = grade; OR = odds ratio. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Includes worst grade of toxicity reported across all weeks of treatment (ie, weeks 1-4 if patient received 55 Gy/20 fx/4 wk or weeks 1-7 if patient received 64 Gy/32 fx/6.5 wk. Values in parentheses are percentages.

P value from Van Elteren (stratified Mann-Whitney) test comparing the distribution of grades between treatment groups.

Odds ratio for G3 or G4 toxicity in RHDVRT group compared with sRT group, adjusted for chemotherapy randomization.

P value from Mantel-Haenszel test comparing the proportion of G3/4 toxicities between groups, stratified by chemotherapy randomization.

Late toxicity

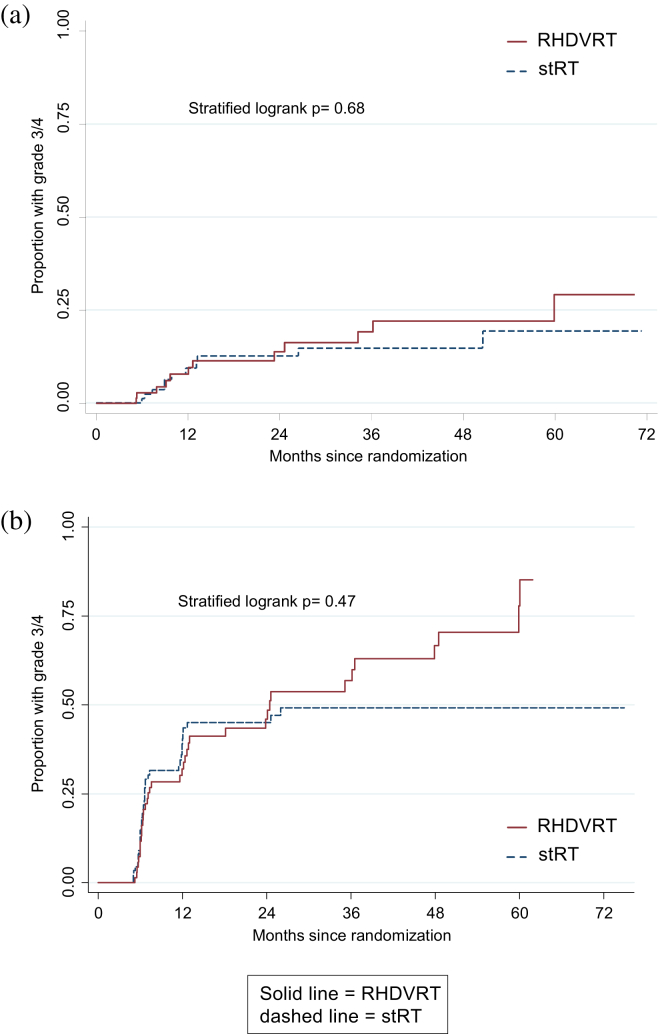

There were no significant differences in the proportions of patients reporting RTOG or LENT/SOM toxicities (Table e1, available online) nor in time to first late G3/4 toxicity (RTOG P=.68, LENT/SOM, P=.47; Fig. 2). At 1 year, G3/4 genitourinary toxicity was reported by 2 of 54 sRT patients (3.7%) and 1 of 53 RHDVRT patients (1.9%) (P=.45). At 2 years proportions were 1 of 42 (2.4%) and 2 of 37 (5.4%), respectively (P=.47).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot of time to first grade 3/4 toxicity using (a) Radiation Therapy Oncology Group and (b) Late Effects of Normal Tissue (Subjective, Objective, Management) toxicity gradings.

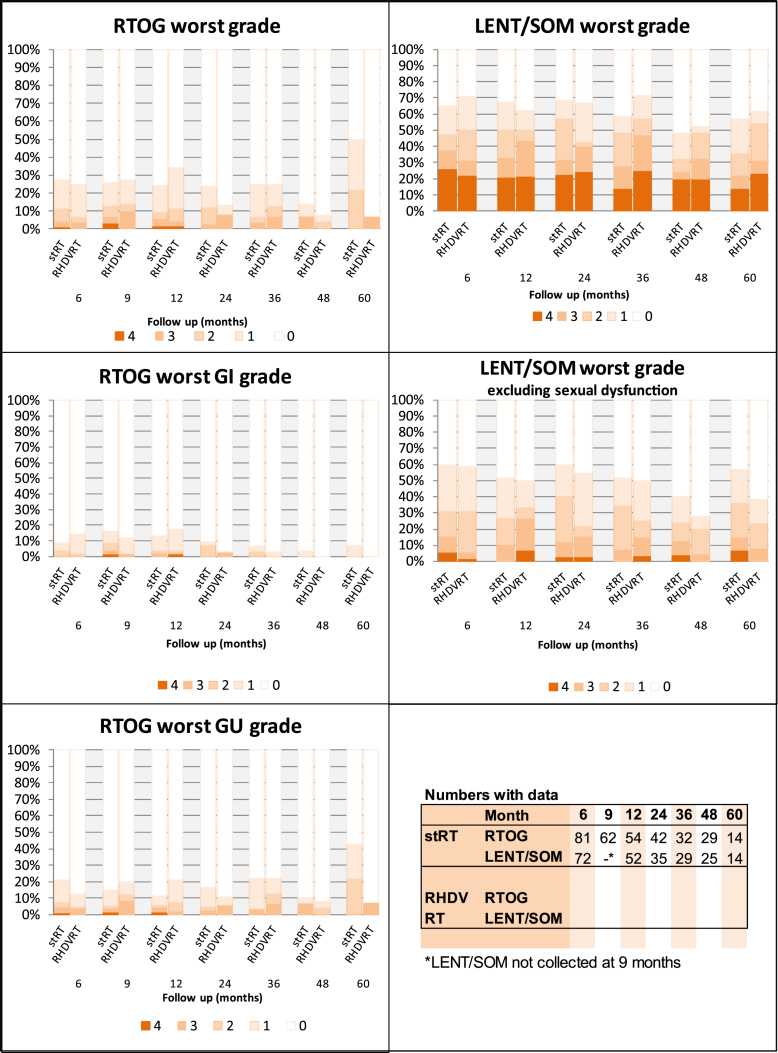

The overall cumulative G3/4 RTOG toxicity rate was 13% (95% CI 8%, 20%) at 2 years (Fig. 2a), whereas the percentage of patients with G3/4 toxicity at any specific point was <8% throughout (Fig. 3) in both groups. Genitourinary toxicity was more prevalent than gastrointestinal; the most common G3/4 toxicities reported were hematuria (7 patients), urethral stricture (6 patients), and cystitis (5 patients).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients reporting late toxicity, by month and grade. GI = gastrointestinal; GU = genitourinary; LENT/SOM = Late Effects of Normal Tissue (Subjective, Objective, Management); RHDVRT = reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy; RTOG = Radiation Therapy Oncology Group; stRT = standard whole-bladder radiation therapy.

The proportion of patients with G3/4 toxicity was higher on the LENT/SOM scale (2-year actuarial rate of 46% [95% CI 37%, 54%]) than on the RTOG scale. However, the most common LENT/SOM G3/4 toxicity was sexual dysfunction (occurring in 57 of 76 patients reporting a G3/4 LENT/SOM toxicity); it was the only G3/4 LENT/SOM symptom in 36 patients and predated treatment in 38 of 57 (67%), so was not a treatment-emergent side-effect. The LENT/SOM 2-year actuarial G3/4 rate was 20% (95% CI 14%, 28%) when excluding sexual dysfunction.

Bladder capacity

Data on change in bladder capacity are relatively incomplete, being available for 51 and 36 patients to 1 and 2 years, respectively. In both groups median bladder capacity was lower at 1 year than at baseline. Adjusted mean reduction in bladder capacity in the RHDVRT group was less than in the sRT group, but the difference was not significant (year 1: by 30.2 mL [95% CI −91.3, 151.6], P=.62; year 2: by 76.0 mL [95% CI −44.9, 197.0], P=.21).

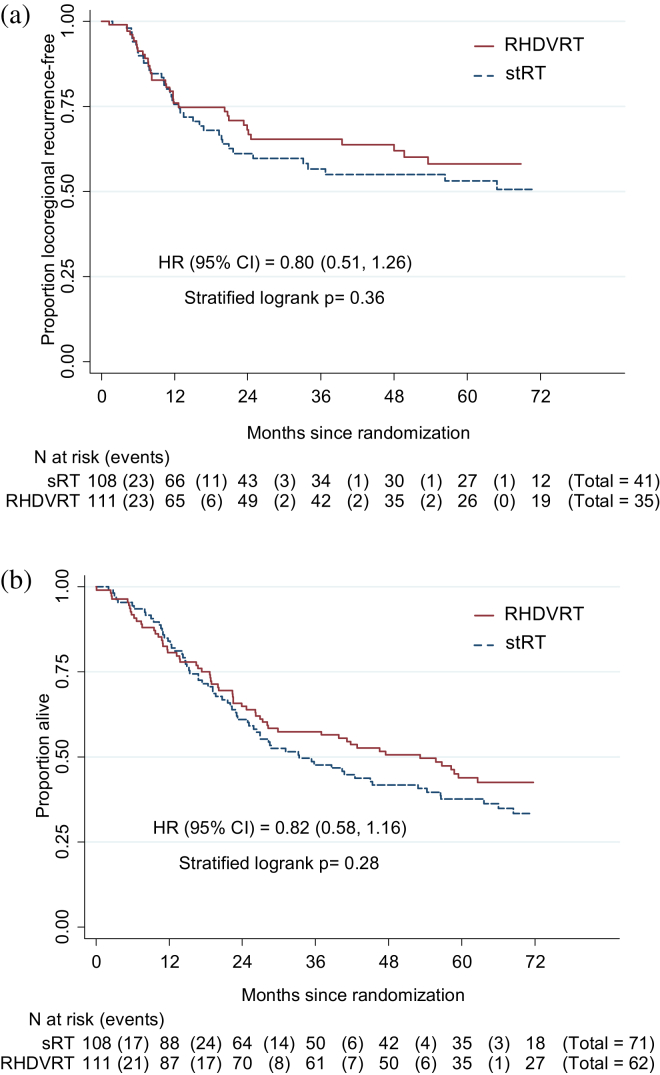

Local control

Two-year LRRF rate was, for sRT: 61% (95% CI 50%, 71%); for RHDVRT: 64% (52%, 73%) (Fig. 4a). The 95% CI for absolute difference in LRRF rate at 2 years excluded RHDVRT, being 10% worse in the ITT population (RHDVRT improvement 6.4% [−7.3%, 16.8%]) but not in the per-protocol population (RHDVRT improvement 2.6% [−12.8%, 14.6%]); therefore, noninferiority could not be formally concluded. Of 76 first locoregional recurrences reported, 39 were noninvasive bladder, 26 were invasive bladder, and 10 were in pelvic nodes (1 unknown). Twenty-six patients (11.9%) (13 sRT, 13 RHDVRT) have undergone cystectomy; time to cystectomy is comparable between treatment groups (log–rank: P=.78; 2-year rate, for sRT: 10.2% [95% CI 5.2%, 18.8%], for RHDVRT: 11.7% [6.6%, 20.1%]). Of 26 cystectomies, 23 (10 sRT, 13 RHDVRT) were for disease recurrence, 1 patient decided to have cystectomy before radiation therapy (sRT), and only 2 patients (both sRT) have had salvage cystectomy for radiation therapy side effects.

Fig. 4.

(a) 2Kaplan-Meier plot of time to locoregional recurrence. Cox model estimated absolute difference in locoregional recurrence-free rate (95% confidence interval) at 2 years: 6.4% (−7.3%, 16.8%). First locoregional recurrence (standard whole-bladder radiation therapy [sRT] vs reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy [RHDVRT]) was noninvasive for 21 (19.4%) vs 18 (16.2%), invasive for 15 (13.9%) vs 11 (9.9%), in the pelvic nodes for 5 (4.6%) vs 5 (4.5%), and unknown for one RHDVRT patient. (b) Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival by randomized group. Cox model estimated absolute difference (95% confidence interval) at 2 years: 4.7% (−6.0%, 13.4%).

Overall survival

Five-year survival rates were 38% (95% CI 28%, 47%) for sRT and 44% (34%, 53%) for RHDVRT (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

BC2001 is the largest randomized trial of radiation therapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. It concluded that 5FU and MMC chemo-radiation therapy was significantly better than radiation therapy alone in terms of LRRF survival (hazard ratio 0.68 [95% CI 0.48, 0.96], P=.03) (12). We have now also demonstrated that delivering at least 75% of dose to the uninvolved bladder is deliverable across multiple sites without obvious detriment to local disease control or survival (although noninferiority could not be formally confirmed).

We were unable to demonstrate that RHDVRT results in the anticipated reduction in toxicity. The statistical power to demonstrate effects in the radiation therapy volume comparison was limited in part owing to early closure of this component of the 2 × 2 factorial randomization, as a result of slow accrual. Further, the overall incidence of late RTOG toxicity was less than predicted from the single-center pilot study. This may be due to improvements in treatment technique but more likely suggests that either the previous study overestimated toxicity or there is underreporting of symptoms using the RTOG scale. The incidence of adverse events was consistent with that in a series of 4 RTOG trials including 285 patients (17), in which throughout all follow-up, RTOG G3 late genitourinary and gastrointestinal toxicity was seen in 5.7% and 1.9% of patients, respectively, despite the use of concomitant chemotherapy. The reported rate of symptoms in our study was higher using the LENT/SOM score—likely a reflection of the broader scope and multidimensionality of the scale (with objective, subjective, and management component scores). An alternative explanation for the lack of an effect is that the volume reduction was not ambitious enough or that it did not spare the relevant anatomic structures sufficiently to achieve clinically detectable reductions in toxicity. Modeling work on a subset of patients suggests that although the volume reduction achieved was variable, the probability of any late bowel toxicity was proportional to the overall bowel volume treated (18).

Despite an age range significantly higher than most cystectomy series, and a significant proportion with a residual mass after transurethral resection of bladder tumor, LRRF rates of more than 60% were achieved at 2 years. More than half of first locoregional relapses seen were non–muscle-invasive and thus potentially treatable with local therapy. These results were achieved with radiation therapy targeted at the bladder alone, with low rates of nodal recurrence suggesting that the value of specific nodal irradiation is limited in this setting—a view supported by the results of a recently published randomized trial that showed no difference in outcome between bladder-only and bladder and pelvic radiation therapy (19). Only 26 of 219 BC2001 radiation therapy comparison patients (12%) have undergone salvage cystectomy, a rate lower than in historical series 5, 20 but similar to that seen in more recent data (21). Some patients treated may not be fit enough for cystectomy, but this lower cystectomy rate could represent case selection, better pretreatment cystoscopic resection, better radiation therapy techniques, the use of neoadjuvant or concomitant chemotherapy (12), or a combination of these factors.

Our results suggest that modern radiation therapy can be used to treat bladder cancer with a low risk of severe late toxicity, maintaining a well-functioning bladder with normal or near-normal capacity in most patients even when combined with synchronous chemotherapy (11). Reduced high-dose volume radiation therapy can achieve similar tumor control outcomes to conventional whole-bladder radiation therapy, although to date we have not demonstrated that this approach translates to a reduction in radiation therapy related side effects. The introduction of image-guided treatment and better tumor localization brings the promise of greater reductions in uninvolved bladder and small-bowel irradiation (22) and thus further potential for reductions in side effects. We believe that this approach is valid both to reduce risks for patients and to enable strategies of dose escalation either through direct radiation therapy dose increases or the use of additional radiosensitizers. Further studies to assess such strategies are encouraged.

The overall low rates of clinically significant toxicity combined with low rates of invasive bladder cancer relapse confirm that (chemo)radiation therapy treatment is a valid option for the treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Footnotes

BC2001 (Current Controlled Trials number, ISRCTN68324339 [controlled-trials.com]) was supported by Cancer Research UK (CRUK/01/004, C547/A2606; C547/A6845; C9764/A9904, C1491/A9895). Trial recruitment was facilitated within centers by the National Institute for Health Research Cancer Research Network.

The Trial Management Group (TMG) interpreted results, and its members also served as the writing committee and take responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the data. The decision to submit the manuscript for publication was made jointly by the TMG, Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) and Trial Steering Committee(TSC). All authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the reported data; all attest that this report is in concordance with the study protocol.

The following clinicians entered patients into the radiation therapy volume randomization of the BC2001 trial (TMG members indicated by ∗): R. Huddart∗, Royal Marsden NHSFT (37 patients); N. James∗, University Hospitals Birmingham NHSFT (27); F. Adab, University Hospital of North Staffordshire (18); D. Sheehan, Royal Devon and Exeter NHSFT (11); I. Syndikus, Clatterbridge Cancer Centre NHSFT (10); S. Gibbs, BHR University Hospitals NHS Trust (7); P. Jenkins∗, Gloucestershire Hospitals NHSFT (7); P. Crellin, Dorset County Hospital NHSFT (7); T. Sreenivasan, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust (7); D. Bloomfield, Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals (7); S. Beesley, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust (7); J. Littler, Clatterbridge Cancer Centre NHSFT (6); V. Khoo, Royal Marsden NHSFT (6); N. Srihari, Royal Shrewsbury Hospitals NHS Trust (5); H. Newman, University Hospitals Bristol NHSFT/Royal United Hospital Bath NHS Trust (5); A. Cook, Gloucestershire Hospitals NHSFT (5); A. Samanci, Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust (5); J. Graham, Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre/University Hospitals Bristol NHSFT (4); J. Wallace, Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre (4); A. Bahl, Royal United Hospital Bath NHS Trust (3); R. McMenemin, Newcastle Hospitals NHSFT (3); J. O'Sullivan, Belfast City Hospital (3); T. Roberts, Newcastle Hospitals NHSFT (2); D. Stewart, Belfast City Hospital (2); J. Bowen, Gloucestershire Hospitals NHSFT (2); F. McKinna, East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust/Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals (2); M. Panades, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust (2); H. Van der Voet, South Tees Hospitals NHSFT (2); M. Carr, Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust (1); J. Glaholm, Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust (1); R. Subramanian, BHR University Hospitals NHS Trust (1); J. Harney, Belfast City Hospital (1); D. Dodds, Wishaw General Hospital (1); H. Taylor, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust (1); A. Birtle, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHSFT (1); M. Churn, Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust (1); R. Eakin, Belfast City Hospital (1); N. Hodson, Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals (1); M. Russell, Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre (1); P. Wells, Whipps Cross University Hospital (1); and R. Beard, Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Trust (1). Other TMG members were C. Hendron, J. Barnwell, R. Lewis, R. Waters, E. Hall, S. Hussain, C. Rawlings, M. Crundwell, and J. Tremlett.

Conflict of interest: none.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at www.redjournal.org

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2008. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed August 24, 2010.

- 2.Stein J.P., Lieskovsky G., Cote R. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: Long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncology. 2001;19:666–675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodel C. Combined-modality treatment and selective organ preservation in invasive bladder cancer: Long-term results. J Clin Oncology. 2002;20:3061–3071. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Clinical Excellence . NICE; London: 2002. Guidance on Cancer Services. Improving Outcomes in Urological Cancers: The Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooke P., Dunn J., Latief T. Long-term risk of salvage cystectomy after radiotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2000;38:279–286. doi: 10.1159/000020294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan W., Quilty P.M. The results of a series of 963 patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder primarily treated by radical megavoltage X-ray therapy. Radiother Oncol. 1986;7:299–310. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(86)80059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Werf-Messing B.H., van Putten W.L. Carcinoma of the urinary bladder category T2,3NXM0 treated by 40 Gy external irradiation followed by cesium137 implant at reduced dose (50%) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:369–371. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowan R., McBain C., Ryder W. Radiotherapy for muscle-invasive carcinoma of the bladder: Results of a randomized trial comparing conventional whole bladder with dose-escalated partial bladder radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emami B., Lyman J., Brown A. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:109–122. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90171-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huddart R., Norman A., Shahidi M. The effect of reducing the high dose volume on toxicity of radiotherapy in the treatment of bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(Suppl. 2) doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2006.04.008. A3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain S.A., Moffitt D.D., Glaholm J.G. A phase I-II study of synchronous chemoradiotherapy for poor prognosis locally advanced bladder cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:929–935. doi: 10.1023/a:1011133820532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James N.D., Hussain S.A., Hall E. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1477–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobin L.H., Fleming I.D. TNM classification of malignant tumors, fifth edition (1997). Union Internationale Contre le Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer. 1997;80:1803–1804. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971101)80:9<1803::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program . Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 1998. Common Toxicity Criteria, Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox J.D., Stetz J., Pajak T.F. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1341–1346. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin P., Constine L.S., Fajardo L.F. RTOG Late Effects Working Group. Overview. Late Effects of Normal Tissues (LENT) scoring system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1041–1042. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Efstathiou J.A., Bae K., Shipley W.U. Late pelvic toxicity after bladder-sparing therapy in patients with invasive bladder cancer: RTOG 89-03, 95-06, 97-06, 99-06. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4055–4061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald F., Hall E., James N. Defining bowel dose constraints for bladder radiotherapy: Using data from patients entered into phase III randomised trial. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2009;7:163–164. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tunio M.A., Hashmi A., Qayyum A. Whole-pelvis or bladder-only chemoradiation for lymph node-negative invasive bladder cancer: Single-institution experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e457–e462. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gospodarowicz M.K., Hawkins N.V., Rawlings G.A. Radical radiotherapy for muscle invasive transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: Failure analysis. J Urol. 1989;142:1448–1453. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39122-x. discussion 1453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Efstathiou J.A., Spiegel D.Y., Shipley W.U. Long-term outcomes of selective bladder preservation by combined-modality therapy for invasive bladder cancer: The MGH experience. Eur Urol. 2012;61:705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lalondrelle S., Huddart R. Improving radiotherapy for bladder cancer: An opportunity to integrate new technologies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2009;21:380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.