Abstract

Omalizumab has been shown to be effective in chronic urticaria (CU) patients in numerous reports. However, it remains unknown whether there are specific phenotypes of CU that are more responsive to omalizumab therapy. We sought to identify CU phenotypes responsive to treatment with omalizumab by characterizing patients and their response patterns. A retrospective chart review analysis of refractory CU patients unresponsive to high-dose H1-blockers and immunomodulators and subsequently treated with omalizumab at the University of Wisconsin Allergy Clinic was performed with particular focus on their autoimmune characteristics, response to therapy, and dosing parameters. We analyzed 19 refractory CU patients (16 patients failed or had toxic side effects to immunomodulators) treated with omalizumab with an overall response rate of 89% (17/19). Of these 19 patients, 9 patients (47%) had a complete response, 8 patients (42%) had a partial response, and 2 patients (11%) had no response. In comparing the response patterns to omalizumab, we found no statistically significant differences among “autoimmune positive” versus “autoimmune negative” patients. No statistically significant differences in responses were observed when comparing demographic parameters including age, gender, IgE levels, or dosing regimen. Our study shows that omalizumab has robust efficacy in refractory CU patients regardless of their autoimmune status, age, gender, IgE levels, or dosing protocol.

Keywords: Age, ANA, antithyroid antibodies, autoimmune, CU Index, gender, high-dose antihistamine, IgE, omalizumab, urticaria

Chronic urticaria (CU) is a debilitating skin condition characterized by the presence of intensely pruritic lesions occurring intermittently or continuously for >6 weeks that impacts millions of patients worldwide. CU is thought to have the most impact on quality of life of any allergic disease and is similar in severity to triple-vessel coronary artery disease.1,2 Because the cause of CU is not known, it is often referred to as chronic spontaneous urticaria or chronic idiopathic urticaria. However, in 35–50% of patients, an autoimmune mechanism with autoantibodies to the α-chain of the high-affinity IgE receptor or IgE itself may underlie the pathophysiology of the disease.3,4 Numerous commercial basophil histamine release assays have been developed and are available to identify an autoimmune etiology. In our previous retrospective analysis of chronic idiopathic urticaria patients, we found that a positive CU index (IBT-ViraCor Laboratories, Lenexa, KS) correlated with a refractory phenotype that is less responsive to the use of H1/H2-histamine receptor blockers with or without leukotriene receptor antagonists.5 Furthermore, we investigated the usefulness of obtaining other surrogate autoimmune biomarkers such as an antinuclear antibody (ANA) or antithyroid antibodies and found that the combination of a positive ANA with either antithyroglobulin (ATG) or antimicrosomal (ATPO) antibody as well as a positive ANA independently also correlated with a refractory outcome, albeit to a lesser degree than a positive CU index.6

Current guidelines recommend a stepwise approach to the management of CU, initially, with the use of nonsedating H1-antihistamines up to 4× Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved dosing.7 Second-line therapy includes supplementation with H2-blockers and leukotriene modifiers. Immunomodulators (cyclosporine, mycophenolate, tacrolimus, hydroxychloroquine, and sulfasalazine) are used as third-line agents to help achieve control in many refractory patients. Given the toxicity profile of these agents, there is interest in the use of omalizumab for CU. Omalizumab is a humanized, monoclonal antibody against the cε3 domain of IgE near the binding site for FcεRI and FcεRII. Omalizumab is approved for patients ≥12 years old. Interestingly, in the past several years, omalizumab has seen its use expand beyond the realm of asthma.8–15 More importantly, recent studies of omalizumab in refractory CU have also shown efficacy.15–18

Because of its high cost, omalizumab will not be an economically viable option for all CU patients. Therefore, determining “CU phenotype(s)” in which omalizumab is effective could identify subsets of patients for which omalizumab would be the preferred choice. To address this issue, we performed a retrospective study of refractory CU patients treated with omalizumab at our academic allergy clinic setting over the past 3 years to identify CU phenotypes, if any, that are more responsive to omalizumab therapy.

METHODS

Study Design and Analyses

This study is a University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board–approved retrospective review of patients with a diagnosis of CU who were treated with omalizumab between 2009 and 2012. CU was defined as having episodes of hives occurring either intermittently or continuously for a period of >6 weeks. Patients were excluded if they had primarily acute urticaria, food or drug-related urticaria, vasculitis (based on clinical symptoms and appearance of persistent lesions), mastocytosis, or exclusively angioedema without evidence of urticaria. Demographic data including age and sex were collected. Laboratory data including IgE, ANA, ATG, ATPO, and CU index levels were obtained. For all laboratory data obtained, reference laboratory guidelines for normal levels were used to define negative or positive tests. For IgE level, two commercial laboratories were used with normal reference ranges of 0–114 IU/mL and 0–180 IU/mL. A value above each respective upper limit was categorized as “IgE elevated.” For the CU index, two commercial laboratories were also used with normal reference ranges of 0–10 and 0–16, and a value above each upper limit was categorized as a positive result. Detailed information on urticaria medication use was collected including omalizumab dosing and duration for all patients. Given that dose-ranging studies were not available at the start of this study, omalizumab was initially dosed using existing nomograms for asthma based on IgE level and weight. However, some patients were subsequently treated with a fixed dose of omalizumab. Response to omalizumab was based on a review of the medical record and categorized as complete (full resolution of symptoms), partial (any subjective or objective improvement in symptoms), or none.

Exact contingency table (r × c) analyses were performed to determine statistical significance among the correlations, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. Not all patients had every biomarker measured, and therefore analyses were performed using the respective subset of patients.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

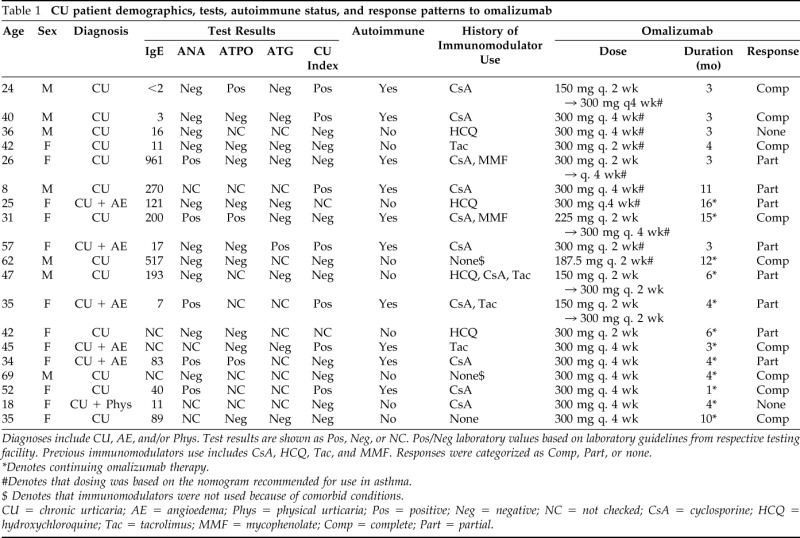

We collected demographic information, laboratory data, and dosing/response to omalizumab in 19 patients (7 male and 12 female subjects) treated with omalizumab for CU (Table 1). The mean age of subjects was 38.3 with a range of 8–69 years. The mean duration of therapy was 6.05 months with a range of 1–16 months. CU index was available for 17 of 19 subjects, ANA in 15 subjects, ATPO in 12 subjects, ATG in 10 subjects, and IgE in 16 subjects. Sixteen of 19 subjects had an antecedent use of an immunomodulator and had either failed therapy or experienced a toxic side effect prompting the use of omalizumab.

Table 1.

CU patient demographics, tests, autoimmune status, and response patterns to omalizumab

Diagnoses include CU, AE, and/or Phys. Test results are shown as Pos, Neg, or NC. Pos/Neg laboratory values based on laboratory guidelines from respective testing facility. Previous immunomodulators use includes CsA, HCQ, Tac, and MMF. Responses were categorized as Comp, Part, or none.

*Denotes continuing omalizumab therapy.

#Denotes that dosing was based on the nomogram recommended for use in asthma.

$ Denotes that immunomodulators were not used because of comorbid conditions.

CU = chronic urticaria; AE = angioedema; Phys = physical urticaria; Pos = positive; Neg = negative; NC = not checked; CsA = cyclosporine; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; Tac = tacrolimus; MMF = mycophenolate; Comp = complete; Part = partial.

Correlation of Demographic Characteristics to Omalizumab Response

Omalizumab was administered at either 2- or 4-week intervals for varying time periods. Sixteen of 19 patients presented in this case series were treated with an immunomodulator (cyclosporine, mycophenolate, tacrolimus, or hydroxychloroquine), and all 19 patients required at least one steroid burst in the 6 months before initiating omalizumab therapy.

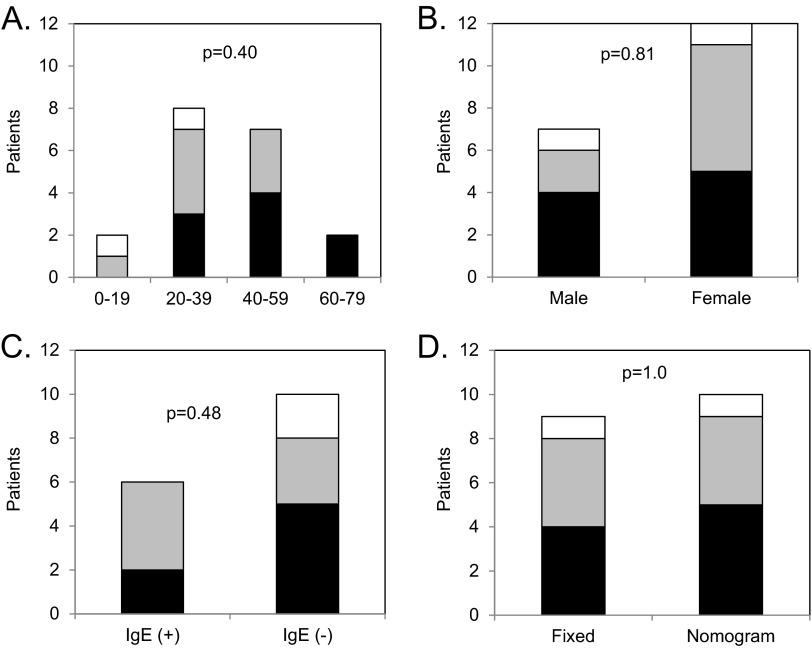

Among various age groups, response patterns to omalizumab were not significantly different (p = 0.40) with 47% of subjects showing complete response, 42% showing a partial response, and 11% showing no response. The majority of patients were >18 years old, which reflects the natural predominance of CU in an older population. No differences were observed in response patterns to omalizumab between different age groups (Fig 1 A). We found similar response patterns to omalizumab in male subjects (57% complete, 29% partial, and 14% none) and female subjects (42% complete, 50% partial, and 8% none) as shown in Fig. 1 B. The difference in response patterns between male and female subjects did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.81).

Figure 1.

Response patterns to omalizumab. The number of patients on y-axis with complete (black bar), partial (gray bar), or no (white bar) response are shown for subgroups separated based on (A) age, (B), gender, (C) IgE level, and (D) dosing protocol. The p values for statistical comparison of response patterns are shown in each panel.

Sixteen of 19 patients in our study had IgE levels obtained. Among those patients, 6 had elevated IgE levels and 10 had normal values. No statistically significant differences (p = 0.48) in response patterns to omalizumab were noted between CU patients with elevated and normal IgE levels (Fig 1 C). With regard to omalizumab dosing protocol, 10 patients had nomogram-based dosing and 9 patients had fixed dosing with no statistically significant differences in response patterns (p = 1.0) noted between either protocol (Fig 1 D).

Autoimmune Status and Omalizumab Response

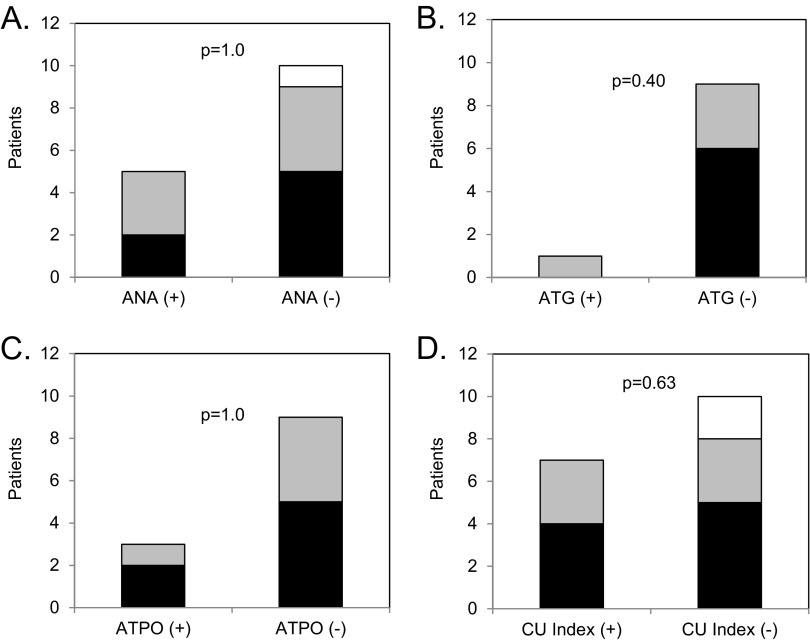

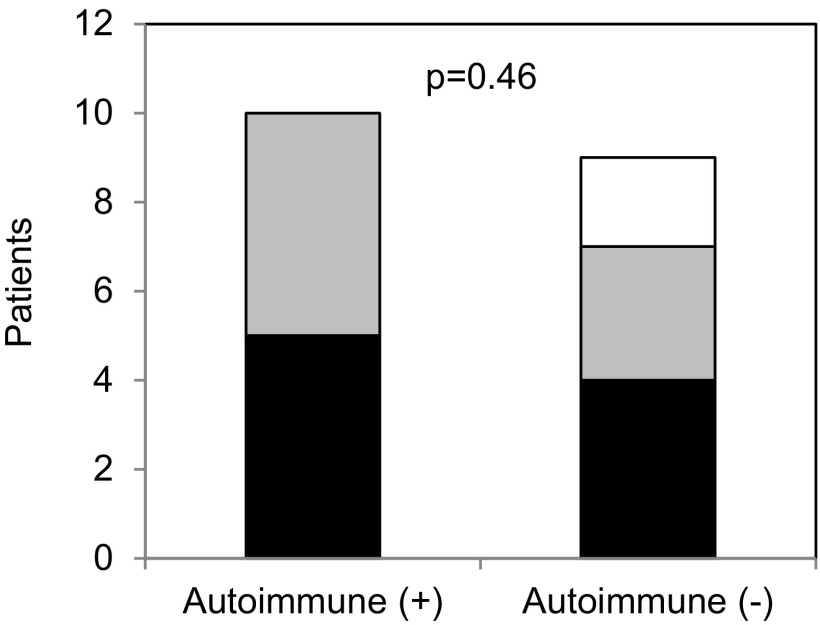

We examined omalizumab response patterns to individual autoimmune biomarkers. As shown in Fig. 2, no significant differences were observed in response patterns to omalizumab when we correlated it individually to ANA, ATG, ATPO, or CU index status of patients (p = 1.0, p = 0.4, p = 1.0, and p = 0.63, respectively). Overall, autoimmune status of positive or negative in the 19 patients was based on whether they had at least one positive autoimmune biomarker (ANA, ATG, ATPO, or CU index) resulting in 10 patients being designated as “autoimmune positive” and 9 patients designated as “autoimmune negative.” As shown in Fig. 3, there were similar proportions (p = 0.46) of patients in each category (complete, partial, or no response) among the autoimmune positive (50, 50, and 0%, respectively) compared with the autoimmune negative group (44, 33, and 22%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Response patterns of omalizumab to individual autoimmune markers. The number of patients on y-axis with complete (black bar), partial (gray bar), or no (white bar) response are shown for subgroups separated based on (A) antinuclear antibody (ANA), (B) antithyroglobulin (ATG), (C) antithyroperoxidase (ATPO), and (D) chronic urticaria (CU) index. Positive (+) and negative (−) for ANA, ATPO, ATG, and CU index were based on standards from the respective testing laboratory. The p values for statistical comparison of response patterns are shown in each panel.

Figure 3.

Response patterns of omalizumab to overall autoimmune status. The number of patients on y-axis with complete (black bar), partial (gray bar), or no (white bar) response are shown for subgroups with any positive autoimmune marker (+) and no positive autoimmune marker (−). The p value for statistical comparison of response patterns is shown.

DISCUSSION

In this study of refractory CU patients, we report an overall response rate to omalizumab treatment of 89% with 47% showing a complete response, 42% showing a partial response, and 11% showing no response. With subgroups based on age, gender, IgE status, and dosing protocol, we observed that the response patterns to omalizumab were similar with no statistically significant differences. In comparing the response to omalizumab based on autoimmune status, we found similar proportions of complete and partial responders in “autoimmune positive” and “autoimmune negative” patients. When examining response based on individual autoimmune biomarkers, we noted similar response patterns to omalizumab in those patients with positive ANA, ATG, ATPO, or CU index compared with those with negative values. Therefore, refractory CU patients had a robust response to treatment with omalizumab regardless of autoimmune status, age, gender, IgE level, and dosing protocol.

Current European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and Global Allergy and Asthma European Network joint guidelines suggest a step-wise approach to the management of CU.7 Although this is appropriate and adequate for a majority of patients, it is inefficient and time-consuming for many refractory patients. Although immunomodulators are an effective option for these refractory patients, they have a toxicity profile that raises concerns about the benefit-to-risk ratio. Omalizumab has emerged as an effective alternative to this conundrum. Saini et al. reported on the dose-dependent efficacy of omalizumab (75, 300, or 600 mg or placebo given once) for CU.18 Also, more recently, Buyukozturk et al. showed improvements in symptom and quality-of-life scores in 14 adult patients treated with omalizumab for 6–20 months.19 Similarly, Nam et al. established significant improvements in symptom scores, quality-of-life measures, and medication use (systemic steroids, immunomodulators, and rescue antihistamines) in CU patients treated with omalizumab for 24 weeks.20 A large placebo-controlled multicenter phase III trial recently showed efficacy of omalizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic idiopathic urticaria who were unresponsive to H1-antihistamines at approved doses.15 The dose of omalizumab used in these studies ranged from 150 mg once a month to 375 mg every 2 weeks and was similar to doses used by patients in our study. Although these results are striking, it remains prudent to consider omalizumab only in those refractory patients who have failed traditional first-/second-line therapies.

Because omalizumab is an expensive treatment option and not FDA-approved for this indication, it is not a viable option for every CU patient. Therefore, its use should be restricted to patients that could preferentially benefit from omalizumab therapy. We recently published data indicating that the presence of a positive CU index or a combination of a positive ANA with antithyroid antibody correlates with a refractory phenotype in CU.5,6 Also, a study by Magen et al. indicated that refractory CU had a higher incidence of positive autologous serum skin test and other laboratory features of low-grade inflammation and platelet activation.21 Several studies have also shown efficacy of omalizumab in specific phenotypes of CU. A report published by Kaplan et al. in 2009 examined the efficacy of omalizumab in a selective cohort of 12 patients who were designated as having an autoimmune basis for their urticaria and noted improvement of symptoms in 11/12 patients.16 In addition, a case series published by Ferrer et al. showed improvement in eight “nonautoimmune” CU patients treated with omalizumab.22 Maurer et al. have shown the efficacy of omalizumab in a cohort of patients with IgE autoantibodies to thyroperoxidase.23 These studies enrolled patients based on the presence or absence of autoimmune markers as inclusion criteria. In contrast, our study included a mixed cohort of CU patients and examined whether any specific autoimmune marker or clinical characteristics would serve as predictor(s) of responsiveness to omalizumab. Our results are consistent with the literature suggesting that all phenotypes of CU are responsive to the use of omalizumab.

There are some limitations to our study, including a retrospective design, small study population, and a lack of standard protocol for the assessment and management of CU. Because of the retrospective nature of this study, response was recorded as a categorical result (complete, partial, or none) based on a subjective review of the medical record as opposed to using a validated instrument for disease activity such as the urticaria activity score.24 It is also possible that some of our partial responders or nonresponders to omalizumab may have been prematurely categorized because of an insufficient duration of treatment. Therefore, it would be ideal to monitor subjects for a 6- to 12-month period on omalizumab therapy to gauge their response patterns. Also, because a common protocol was not used, each patient did not have every biomarker measured. The small sample size raises questions of whether there are predictors that we were not able to detect; however, given the high rate of response to omalizumab, identification of positive or negative predictor(s) will be very challenging.

Our study also included the use of omalizumab in an 8-year old boy. It should be noted that there is a paucity of data for omalizumab in the pediatric population for this indication. He had refractory CU with angioedema that failed to improve with cyclosporine therapy and required frequent steroid bursts. Omalizumab treatment resulted in a complete resolution of symptoms.

There is considerable interest in understanding the mechanism for disease improvement with use of omalizumab. Previous studies have shown that omalizumab decreases free IgE levels and down-regulates FcεR1 expression on mast cells and basophils.25,26 These mechanisms of action for omalizumab in CU are insufficient explanations given that patients note an improvement in symptoms within days of omalizumab administration.15,18 It has also been proposed that omalizumab may exert some of its effects through direct basophil stabilization18 or have effects on pathogenic IgE antibodies,27 which may explain its rapid onset of action or perhaps there remains an as-yet undetermined mechanism.28

Given the high cost for omalizumab, it will be prudent to consider omalizumab only in those refractory patients who have failed traditional first-/second-line therapies. With regard to safety, omalizumab is exceedingly safe to use as shown from studies in patients with severe allergic asthma.29,30 In our study population, one patient discontinued omalizumab because of severe headaches. Aside from this event, no other adverse reactions were noted in our study subjects. Additional questions remain regarding dosing and duration of omalizumab for refractory CU patients. The dosing in asthma uses a nomogram based on IgE level and weight to calculate the omalizumab dose for patients. Recently, it was indicated that a fixed dose of omalizumab, independent of IgE level or weight, is effective and sufficient for management of CU patients.18 In our study, 10 patients were treated using nomogram-based dosing and 9 patients with fixed dosing protocol with no statistically significant differences in response patterns. The duration of therapy and whether remission can occur remain unanswered questions. Our mean duration of therapy was 6.05 months with a range of 1–16 months. As stated previously, it would be prudent to treat such refractory patients for a duration of 6–12 months to ascertain their true response patterns. A more recent study did show long-term efficacy for omalizumab in CU patients who were treated for 9–24 months.31 Future studies using a standardized protocol and longer-term treatment inclusive of multiple CU phenotypes will be required to determine whether remission can occur and the optimal dosing and duration needed to achieve it. Given the current body of evidence for omalizumab in CU and its potential to induce remission, omalizumab, despite being an expensive alternative at present, may in the long run help to defray health care costs for refractory CU patients.

In conclusion, our study suggests that omalizumab has robust efficacy in refractory CU patients regardless of their autoimmune status, age, gender, IgE level, or dosing schedule. Our findings reinforce the published data on the use of omalizumab in CU patients. It is our hope that the existing repository of data and future randomized-controlled studies will pave the way for a successful FDA application and omalizumab will be included in our armamentarium to treat refractory CU patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. William Busse for his contribution in successfully treating many of the CU patients who were included in this study. They also thank Sue Westphal, R.N., and Beth Schwantes, B.S., for assistance with data collection and administrative aspects of the project.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1. O'Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, et al. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol 136:197–201, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Poon E, Seed PT, Greaves MW, Kobza-Black A. The extent and nature of disability in different urticarial conditions. Br J Dermatol 140:667–671, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hide M, Francis DM, Grattan CE, et al. Autoantibodies against the high-affinity IgE receptor as a cause of histamine release in chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med 328:1599–1604, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrer M, Kinét JP, Kaplan AP. Comparative studies of functional and binding assays for IgG anti-Fc(epsilon)RI(alpha) (alpha-subunit) in chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 101:672–676, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biagtan MJ, Viswanathan RK, Evans MD, Mathur SK. Clinical utility of the Chronic Urticaria Index. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127:1626–1627, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Viswanathan RK, Biagtan MJ, Mathur SK. The role of autoimmune testing in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 108:337–341.e1, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: Management of urticaria. Allergy 64:1427–1443, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leung DY, Sampson HA, Yunginger JW, et al. Effect of anti-IgE therapy in patients with peanut allergy. N Engl J Med 348:986–993, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Foroughi S, Foster B, Kim N, et al. Anti-IgE treatment of eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol 120:594–601, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Molderings GJ, Raithel M, Kratz F, et al. Omalizumab treatment of systemic mast cell activation disease: Experiences from four cases. Intern Med 50:611–615, 2011. (PubMed PMID: 21422688.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pitt TJ, Cisneros N, Kalicinsky C, Becker AB. Successful treatment of idiopathic anaphylaxis in an adolescent. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126:415–416, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Belloni B, Ziai M, Lim A, et al. Low-dose anti-IgE therapy in patients with atopic eczema with high serum IgE levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol 120:1223–1225, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park SY, Choi MR, Na JI, et al. Recalcitrant atopic dermatitis treated with omalizumab. Ann Dermatol 22:349–352, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim DH, Park KY, Kim BJ, et al. Anti-immunoglobulin E in the treatment of refractory atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 38:496–500, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maurer M, Rosen K, Hsieh HJ, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med 368:924–935, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaplan AP, Joseph K, Maykut RJ, et al. Treatment of chronic autoimmune urticaria with omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol 122:569–573, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Magerl M, Staubach P, Altrichter S, et al. Effective treatment of therapy-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria with omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126:665–666, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saini S, Rosen KE, Hsieh HJ, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of single-dose omalizumab in patients with H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128:567–573.e1, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buyukozturk S, Gelincik A, Demirturk M, et al. Omalizumab markedly improves urticaria activity scores and quality of life scores in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients: A real life survey. J Dermatol 39:439–442, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nam YH, Kim JH, Jin HJ, et al. Effects of omalizumab treatment in patients with refractory chronic urticaria. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 4:357–361, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Magen E, Mishal J, Zeldin Y, Schlesinger M. Clinical and laboratory features of antihistamine-resistant chronic idiopathic urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc 32:460–466, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferrer M, Gamboa P, Sanz ML, et al. Omalizumab is effective in nonautoimmune urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127:1300–1302, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maurer M, Altrichter S, Bieber T, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic urticaria who exhibit IgE against thyroperoxidase. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128:202–209e5, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mlynek A, Zalewska-Janowska A, Martus P, et al. How to assess disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria? Allergy 63:777–780, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eckman JA, Sterba PM, Kelly D, et al. Effects of omalizumab on basophil and mast cell responses using an intranasal cat allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125:889–895.e7, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beck LA, Marcotte GV, MacGlashan D, et al. Omalizumab-induced reductions in mast cell Fce psilon RI expression and function. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114:527–530, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 12:406–411, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sanchez J, Ramirez R, Diez S, et al. Omalizumab beyond asthma. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 40):306–315, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chipps BE, Figliomeni M, Spector S. Omalizumab: An update on efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe allergic asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 33:377–385, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy 39:788–797, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Song CH, Stern S, Giruparajah M, et al. Long-term efficacy of fixed-dose omalizumab for patients with severe chronic spontaneous urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 110:113–117, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]