Abstract

Importance

Child maltreatment is a serious public health problem that disproportionately affects infants and toddlers. In the interest of informing prevention and intervention efforts, this study examined pregnant women’s attributions about infants as a risk factor for child maltreatment and harsh parenting during their children’s first and second years. We also provide specific methods for practitioners to assess hostile attributions.

Objective

To evaluate pregnant women’s hostile attributions about infants as a risk factor for early child maltreatment and harsh parenting.

Design

Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting

A small Southeastern city and its surrounding county.

Participants

A diverse, community-based sample of 499 pregnant women.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Official records of child maltreatment and mother-reported harsh parenting behaviors. Hostile attributions were examined in terms of women’s beliefs about infants’ negative intentions (eg, the extent to which infants purposefully dirty their diapers).

Results

Mothers’ hostile attributions increased the likelihood that their child would be maltreated by the age of 26 months (adjusted odds ratio, 1.26 [90% CI, 1.02–1.56]). Mothers who made more hostile attributions during pregnancy reported engaging in more harsh parenting behaviors when their children were toddlers (β=0.14, P<.05). Both associations were robust to the inclusion of 7 psychosocial covariates.

Conclusions and Relevance

A pregnant woman’s hostile attributions about infant’s intentions signal risk for maltreatment and harsh parenting of her child during the first years of life. Practitioners’ attention to women’s hostile attributions may help identify those in need of immediate practitioner input and/or referral to parenting services.

Child maltreatment is a serious public health problem that disproportionately affects infants and toddlers. In the United States in 2008, 772 000 children, 10.3 of every 1000 (1%), were alleged victims of abuse or neglect.1 Rates for children between birth and 1 year of age were more than twice as high.1 Parents perpetrated 80% of child abuse and neglect cases.1

Child maltreatment is increasingly viewed on a spectrum of negative parenting behaviors because, for example, both spanking and spanking with an object are associated with an increased likelihood of physical abuse.2 Reducing official cases of child maltreatment, as well as negative parenting behavior, requires cross-disciplinary, multipronged initiatives.3 In the interest of informing prevention and intervention efforts, our study examined pregnant women’s attributions about infants as a risk factor for child maltreatment and harsh parenting during their children’s first and second years.

This examination of expectant mothers’ attributions drew on social information processing theory4 and research illustrating associations between attributions of negative intentions and subsequent aggressive behaviors.5 Specifically, individuals who demonstrate hostile attributions about others’ intentions have also been shown to favor retaliatory aggressive responses, even from minor and/or ambiguous provocations, and to evaluate positively such aggressive responses. These patterns have been demonstrated in both children and parents. For example, parents’ hostile attributions have been shown to predict harsh parenting behaviors toward their prekindergarten children.6

Our study focused specifically on expectant mothers’ attributions about the extent to which infants behave with negative intention (eg, purposefully dirty their diapers). Research to date has illustrated some preliminary associations between such attributions and negative and/or abusive parenting behaviors.7–10 In a particularly relevant study of 73 low-income Latino families,9 mothers’ negative attributions, assessed prenatally or shortly after the birth of their child, predicted self-reported harsh parenting behaviors (eg, infant shaking and slapping) 1 year later if infants were also born “at risk” (>2 weeks prematurely or with Apgar scores ≤8). The limitations of this study9 include its small, homogeneous sample and its reliance on self-report for assessing maternal attributions and parenting behaviors.

The present study extends this body of research, with a particular goal of informing practitioners’ consideration of mothers’ hostile attributions as a risk factor for child maltreatment and problematic parenting behaviors. A representative, community-based sample of pregnant women was recruited and followed up longitudinally. The hypothesis tested was that prenatal hostile attributions would predict official reports of child maltreatment between birth and 2 years of age, and mothers’ self-reported harsh parenting behaviors during their child’s second year.

METHODS

All research methods were approved by the first author’s institutional review board. Participants were 499 mothers and their infants from a small southeastern city and its surrounding county. Mothers were recruited during pregnancy by 1 of 3 trained female research assistants in the waiting rooms of prenatal care providers, including a large public health clinic and private obstetrics and gynecology practices. In addition, flyers were posted at these clinics and in other community locations. Potential participants were offered $20 per interview. Of the 383 women approached, 351 (92%) agreed to participate. Another 148 mothers were recruited after responding to the flyer.

Mothers identified themselves as white (non-Latina) (35%), black (non-Latina) (34%), Latina (23%), Asian (3%), biracial or multiracial (3%), or other (1%). At enrollment, mothers ranged in age from 12 to 41 years (mean [SD] age, 27 [5.88] years). Twenty-eight percent of the mothers had not completed high school, 13% had completed high school or a General Education Development certification, and 17% had completed some college or vocational training. Twenty-three percent of the mothers had graduated from college, and 18% had completed a postgraduate degree. Annual family income ranged from $0 to $400 000, with a median of $35 000. Seventy-six percent of the mothers lived with a husband, boyfriend, or partner. Fifty-two percent of the mothers were primiparous. Comparison with population statistics for race, ethnicity, and education for mothers giving birth in the county during the year that study participants were interviewed indicated that the sample is representative of the county from which it is drawn.

During the second half of pregnancy, participants completed a 1-hour, face-to-face interview that included assessments of attributions about infant behavior, family demographics, mental health problems, and social isolation. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish (by a native Spanish speaker), according to the participant’s preference. As part of standard informed consent procedures, approved by the researchers’ institutional review board, participants provided written consent for the research team to access county child protective service records for up to 7 years after their child’s birth. County records were reviewed regularly for the presence of allegations and substantiations of child maltreatment among the participants’ infants.

During their children’s second year (mean [SD] age of child, 16 [1.7] months), 315 (63%) of the 499 mothers (ie, the original sample) participated in brief telephone interviews to confirm their child’s date of birth and sex, and to assess mothers’ self-reported parenting behaviors. Comparisons of the follow-up with the original sample indicated that those mothers who were retained for follow-up were generally more advantaged than those who were not. Mothers who were retained were more likely to be older, to be more educated, to have higher family incomes, and to have reported fewer mental health problems and less social isolation during pregnancy (all P≤.05). Almost all of the children (92%) were born at a gestational age of 37 weeks or more. Approximately half (54%) were boys.

MEASURES

The predictor, the mother’s hostile attributions, was assessed with a short version of the Infant Intentionality Questionnaire,11,12 adapted specifically for our study (eAppendix, jamapeds.com). The mothers completed 13 items that measure attributions of both positive and negative intentions to infants between the ages of 6 and 12 months (eg, “Do babies seek praise when they do something clever?” and “Do babies ignore their mothers to be annoying?”). The mothers responded on a 5-point scale (from never or not at all [1] to always or definitely [5]). Mothers’ “negative intentionality” according to this scale has been associated with self-reported and observed negative parenting behaviors.10

For the purposes of our study, all items were first recoded into dichotomous variables (1=“rarely or never”; 2=“sometimes, often, or always”). Subscales measuring negative intentionality and positive intentionality were created by selecting items with adequate response variability (at least 10% of responses in 1 of the 1/2 categories) and by averaging the items relevant to each subscale (for negative intentionality [4 items]: range, 1–2; mean [SD], 1.18 [0.27]; α=0.67; for positive intentionality [4 items]: range, 1–2; mean [SD], 1.69 [0.29]; α=0.52). The negative and positive intentionality subscales were positively correlated (r=0.19, P<.001). Given this positive correlation, a new variable, hostile attributions, was created to index mothers’ attributions of infants’ negative intentions relative to mothers’ attributions of infants’ overall intentions (=negative intentionality/[negative intentionality + positive intentionality]; recoded onto a 5-point scale to facilitate interpretation; range, 1–5; mean [SD], 3.03 [1.40]).

To measure the first outcome variable, child maltreatment, county records of all child maltreatment reports were reviewed. In accordance with county regulations, information about perpetrators was explicitly excluded from the records available to our research team. Records were reviewed through the child’s age of 26 months. Forty individual children (8%) with at least 1 incident of alleged or substantiated abuse or neglect were identified. There was a total of 79 incidents for these 40 children, with 17 (43%) of the children having more than 1 allegation or substantiation. Of these 79 incidents, 62 (78%) were allegations only, and 17 (22%) were substantiations. For analytic purposes, children were classified as victimized if they had at least 1 allegation or substantiation of abuse or neglect at or before the age of 26 months (maltreatment/no maltreatment= 1/0; 40 of 499 children [8%]). Allegations and substantiations were combined because internal analysis of this county’s records and analyses from a national study have indicated that allegations and substantiations are equally strong predictors of subsequent involvement with child protective services and other concerning outcomes.13,14

The second outcome variable, harsh parenting, was assessed with 4 items from the Parental Cognitions and Conduct Toward the Infant Scale, a psychometrically sound assessment of parental “hostile-reactive” behaviors toward their infants.15,16 Using a 5-point scale, mothers indicated the frequency with which they responded to occasions during the past 3 months when their toddler was “particularly fussy” by being angry with their child, spanking their child, shouting at their child, and shaking their child (from 0=never to 4=more than once per day). Because no mother reported ever shaking her child, that item was omitted. The frequency responses for the 3 remaining items were averaged to create a harsh parenting scale (range, 0–3; mean [SD], 0.64 [0.63]; α=0.73).

Demographic variables included maternal race/ethnicity (dummy coded to white/nonwhite=1/0), age, education (8-point scale from 0=none to 7=postcollege; range, 0–7; mean [SD], 4.36 [2.08]), annual family income (standardized; range, −1.12 to 8.64; mean [SD], 0.00 [1.00]), and a variable indicating whether or not women were first-time mothers (dummy coded to primiparous/multiparous=1/0).

Maternal mental health problems were assessed with 2 questions about prevalence of depressive symptoms and 1 question about anxiety symptoms, adapted from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview short-form.17 Responses were summed to create a 4-point index of total mental health problems (range, 0–3; mean [SD], 0.85 [1.10]).

Social isolation was assessed with 4 vignettes adapted from the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project (Mathematica Policy Research), in which mothers reported the number of people, if any, from whom they could seek help under each of 4 scenarios. Responses to each scenario were coded on a 3-point scale, with higher scores indicating less support (0=2 or more people, 1=1 person, and 2=no people), and averaged to create a single score for social isolation (mean [SD] score, 0.40 [0.50]).

ANALYTIC METHODS

All principal analyses were conducted using Mplus 6,18 with missing values estimated by multiple imputation. For all variables except family income, between 99% and 100% of the data were present. The family income variable was missing 13% of the mothers owing to nonresponse. Logistic regression probed the prediction of mothers’ hostile attributions to child maltreatment. Given the combination of (a) high public health significance of child maltreatment and (b) relatively low rate (8%) of early maltreatment in this and other community-based samples, in order to reduce type II error, the confidence interval for the logistic regression was set to 90%. Linear regression (with a 95% CI) examined the prediction of mothers’ hostile attributions to harsh parenting behaviors. Both regression models included maternal race, age, education, family income, parity, mental health problems, and social isolation as covariates.

RESULTS

Initial analysis of bivariate correlations between all variables indicated, as hypothesized, significant, positive correlations between mothers’ hostile attributions and both outcome variables, child maltreatment and harsh parenting (P<.05). There were also significant bivariate correlations between mothers’ hostile attributions and their mental health problems and social isolation. Mothers’ hostile attributions were negatively correlated with majority (white) race, maternal age, education, and family income. In addition, mothers’ hostile attributions were negatively correlated with parity such that multiparous mothers made more hostile attributions than did primiparous mothers. The outcome variables, child maltreatment and harsh parenting, were not significantly correlated. However, both child maltreatment and harsh parenting were negatively correlated with majority (white) race, maternal age, education, and family income and positively correlated with maternal mental health problems and social isolation.

Table 1 illustrates the results of the logistic regression testing the prediction of mothers’ hostile attributions to child maltreatment between birth and 26 months of age. After statistically covarying the 7 demographic and psychosocial factors, mothers’ hostile attributions increased the likelihood that their child would be maltreated (odds ratio, 1.26 [90% CI, 1.02–1.56]). Thus, for every 1-point increase in mothers’ hostile attributions (1–5 scale), their children had 26% greater odds of being maltreated.

Table 1.

Results of Logistic Regression Testing the Prediction From Mothers’ Prenatal Hostile Attributions to Child Maltreatmenta

| Odds Ratio (90% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Maternal race (1 = white) | 0.95 (0.41–2.20) |

| Maternal age | 0.93 (0.87–1.00) |

| Maternal education | 1.04 (0.84–1.29) |

| Family income | 0.58 (0.28–1.20) |

| Primiparous (1 = yes) | 0.36 (0.18–0.70) |

| Mental health problems | 1.22 (0.96–1.56) |

| Social isolation | 1.26 (0.69–2.31) |

| Hostile attributions | 1.26 (1.02–1.56) |

R2 = .31 (P < .01).

Figure 1 depicts the bivariate association between mothers’ hostile attributions and the probability of their child being maltreated. Children of mothers who received the minimum score of 1 for hostile attributions had a 4% chance of being maltreated, whereas children of mothers who received the maximum score of 5 for hostile attributions had a 15% chance of being maltreated. Almost one-quarter of the children in this sample (113 of 499 [23%]) had mothers who received the maximum score of 5 for hostile attributions. Thus, compared with the sample as a whole(8% maltreated), children whose mothers received a score of 5 for hostile attributions were almost twice as likely to be victimized.

Figure 1.

Probability of child maltreatment, predicted by mothers’ prenatal hostile attributions.

Table 2 illustrates the results of the linear regression testing the prediction of mothers’ hostile attributions to self-reported harsh parenting behaviors during their child’s second year. After statistically covarying the 7 demo graphic and psychosocial factors, there was a positive prediction from mothers’ hostile attributions to harsh parenting behaviors such that mothers who made more hostile attributions during pregnancy also reported more harsh parenting behaviors when their children were toddlers(β = 0.14, P<.05).

Table 2.

Results of Linear Regression Testing the Prediction From Mothers’ Prenatal Hostile Attributions to Harsh Parentinga (N = 315)

| B (SE) | β | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal race (1 = white) | −0.12 (0.09) | −0.10 |

| Maternal age | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.11b |

| Maternal education | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.03 |

| Family income | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.03 |

| Primiparous (1 = yes) | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.09 |

| Mental health problems | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.14c |

| Social isolation | 0.11 (0.09) | 0.09 |

| Hostile attributions | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.14c |

R2 = .14 (P < .001).

P < .10.

P < .05.

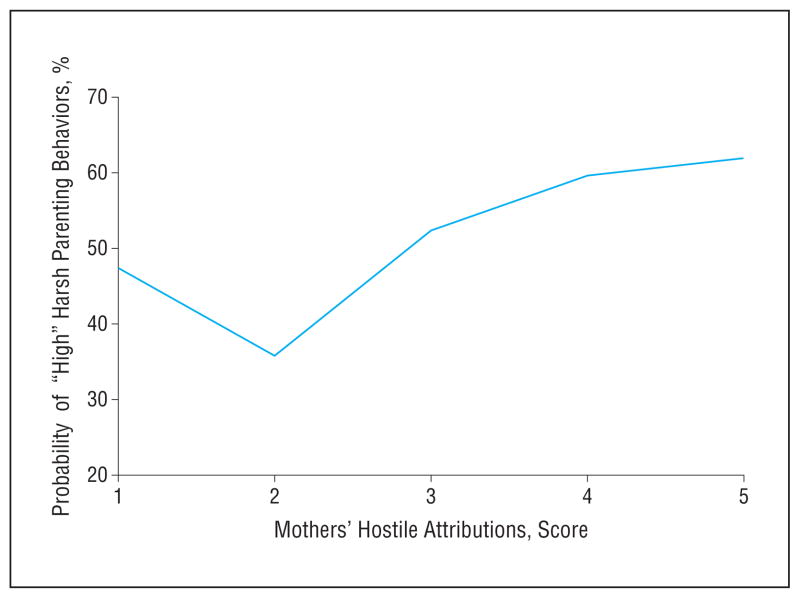

To illustrate this finding further, the harsh parenting scale was dichotomized at the mean into a binary variable reflecting “high” and “low” harsh parenting behaviors. Figure 2 depicts the bivariate association between mothers’ hostile attributions and the probability of their being “high” on harsh parenting behaviors. Mothers who received the minimum score of 1 for hostile attributions had a 47% chance of also being “high” on harsh parenting behaviors, whereas mothers who received the maximum score of 5 for hostile attributions had a 62% chance of being “high” on harsh parenting behaviors. Thus, a 4-point increase in hostile attributions was associated with a 15% greater probability of reporting more harsh parenting behaviors. It is also notable that the association between mothers’ hostile attributions and their harsh parenting behaviors was not completely linear because mothers who received a score of 2 for hostile attributions actually had the lowest probability (ie, 36%) of being “high” on harshness.

Figure 2.

Probability of mothers’ “high” harsh parenting behaviors, predicted by mothers’ prenatal hostile attributions.

DISCUSSION

In the interest of reducing child maltreatment and associated negative parenting behaviors, our study drew on a large and diverse community-based sample to examine pregnant women’s hostile attributions as a risk factor. As hypothesized, prenatal attributions about infants’ hostile intentions predicted official reports of child maltreatment between birth and 2 years of age. This finding was statistically significant (P < .05) at the bivariate level and robust to the inclusion of 7 covariates at P < .10. Prenatal attributions about infants’ hostile intentions also predicted mothers’ self-reported harsh parenting behaviors when their children were approximately 1.5 years of age (P < .05) and remained significant at P < .05 in multivariate analyses. These findings extend previous research on this topic and highlight the value of practitioners attending to mothers’ attributions about infants.

First, mothers’ hostile attributions increased the likelihood that their child would be maltreated, with every 1-point increase in mothers’ hostile attributions associated with 26% greater odds of being maltreated. Compared with the sample as a whole, mothers who received the highest possible score for hostile attributions had children who were almost twice as likely to be victimized. This finding is consistent with prior research and increases confidence in the use of hostile attributions as a risk factor for child maltreatment. Similarly, mothers’ prenatal hostile attributions predicted more self-reported harsh parenting behaviors when their children were toddlers. The 23% of the mothers who received the highest possible score for hostile attributions had a 62% chance of being “high” on harsh parenting behaviors.

It was some what curious that the out come variables, child maltreatment and harsh parenting, were not significantly correlated. Although harsh parenting is clearly negative and undesirable, it may not be sufficiently adverse to predict maltreatment. Conversely, although mothers’ hostile attributions might be dismissed as “only” beliefs (vs behaviors), our findings highlight mothers’ hostile attributions as a risk factor, not only predictive of child maltreatment and harsh parenting behaviors but also associated with demographic and psychosocial indicators of risk (eg, younger maternal age, lower educational level, and social isolation). The finding that multiparous mothers made more hostile attributions than did primiparous mothers further implicates attributions as a maternal psychological characteristic, possibly exacerbated by increasing child-rearing responsibilities, and not necessarily tempered by child-rearing experience. The analysis of diagnostic mental health information, which our study did not include, would be helpful for examining these connections more thoroughly.

A limitation of our study concerns the child maltreatment data, specifically that neither the perpetrator nor the type(s) of maltreatment experienced by the children could be rigorously analyzed. It would be especially important to know if mothers’ attributions led them to perpetrate maltreatment themselves, to have children who are victimized by others, or both. It is likely that a large proportion of the maltreatment cases in our study were perpetrated by mothers because, most commonly, mothers are the actual perpetrators.19 Moreover, even when they are not, they may be considered perpetrators for failing to protect their child from being victimized by someone else (although often in such instances mothers, too, are victims of partner violence). These issues remain to be examined.

In terms of practical implications for reducing child maltreatment and negative parenting behaviors, our study highlights the value of practitioners attending to mothers’ and expectant mothers’ attributions about infants’ intentions. This practice can be accomplished on informal and formal bases. Informally, if anew mother reports, for example, that her baby is repeatedly waking her up during the night because he is “spoiled” or ”naughty,” a practitioner might immediately probe that mother’s attributions and responses. A brief reframing or more intensive parenting intervention addressing such topics as typical infant behavior and nonphysical discipline may well be warranted. A brief cognitive reframing intervention by Bugental and colleagues20 has shown positive effects on harsh parenting behaviors. Dozier’s Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up program is both brief (10 sessions) and intensive, showing positive effects on infant attachment security.21

In addition, the hostile attributions scale analyzed in our study is now available in the form of a brief online assessment (http://www.childandfamilypolicy.duke.edu/engagement/maternal_beliefs.php). Mothers or expectant mothers can complete the 8 questions in an interview or self-administered format, with the resulting score for hostile attributions instantly produced. Formally assessing mothers’ attributions about infants in this brief and user-friendly fashion may elicit less discomfort or defensiveness than existing risk assessments that address factors such as maternal substance use, domestic violence, and trauma history. When high scores for hostile attributions are obtained, practitioners can consider an immediate discussion with the mother and/or referral to parenting services.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant K01MH70378 awarded to Dr Berlin and National Institute on Drug Abuse grants P20DA017589 and P30DA023026 awarded to the Duke University Transdisciplinary Prevention Research Center (principal investigators P. Costanzo and K. Dodge).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Online-Only Material: The eAppendix is available at jamapeds.com.

Additional Contributions: We thank Chongming Yang, PhD, for assistance with data analysis, Adam Zolotor, MD, DrPH, for editorial comments, and Michelle Raymond, MSW, for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: All authors. Acquisition of data: Berlin and Dodge. Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: All authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Dodge and Reznick. Statistical analysis: Berlin and Reznick. Obtained funding: Berlin and Dodge. Administrative, technical, and material support: Dodge. Study supervision: Berlin and Dodge.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Administration on Children, Youth, and Families: Child Maltreatment 2008. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zolotor AJ, Theodore AD, Chang JJ, Berkoff MC, Runyan DK. Speak softly—and forget the stick: corporal punishment and child physical abuse. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(4):364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daro D, Dodge KA. Creating community responsibility for child protection: possibilities and challenges. Future Child. 2009;19(2):67–93. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodge KA. A social information processing model of social competence in children. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Minnesota Symposium in Child Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 77–125. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orobio de Castro B, Veerman JW, Koops W, Bosch JD, Monshouwer HJ. Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: a meta-analysis. Child Dev. 2002;73(3):916–934. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nix RL, Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, McFadyen-Ketchum SA. The relation between mothers’ hostile attribution tendencies and children’s externalizing behavior problems: the mediating role of mothers’ harsh discipline practices. Child Dev. 1999;70(4):896–909. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer WD, Twentyman CT. Abusing, neglectful, and comparison mothers’ responses to child-related and non-child-related stressors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53(3):335–343. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bugental DB, Blue J, Cruzcosa M. Perceived control over caregiving outcomes: Implications for child abuse. Dev Psychol. 1989;25(4):532–539. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.4.532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugental DB, Happaney K. Predicting infant maltreatment in low-income families: the interactive effects of maternal attributions and child status at birth. Dev Psychol. 2004;40(2):234–243. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burchinal M, Skinner D, Reznick JS. European American and African American mothers’ beliefs about parenting and disciplining infants: a mixed-method analysis. Parent Sci Pract. 2010;10(2):79–96. doi: 10.1080/15295190903212604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman R, Reznick JS. Maternal perception and infant intentionality at 4 and 8 months. Infant Behav Dev. 1996;19(4):483–496. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(96)90008-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reznick JS. Inferring Infant Intentionality. Berlin, Germany: VDM Verlag Dr Müller; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Time to leave substantiation behind: findings from a national probability study. Child Maltreat. 2009;14(1):17–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, et al. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: distinction without a difference? Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(5):479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boivin M, Pérusse D, Dionne G, et al. The genetic-environmental etiology of parents’ perceptions and self-assessed behaviours toward their 5-month-old infants in a large twin and singleton sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(6):612–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forget-Dubois N, Boivin M, Dionne G, Pierce T, Tremblay RE, Pérusse D. A longitudinal twin study of the genetic and environmental etiology of maternal hostile-reactive behavior during infancy and toddlerhood. Infant Behav Dev. 2007;30(3):453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen HU. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview short-form (CIDI-SF) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1998;7(4):171–185. doi: 10.1002/mpr.47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Health and Human Services. Administration on Children, Youth, and Families: Child Maltreatment 2006. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bugental DB, Ellerson PC, Lin EK, Rainey B, Kokotovic A, O’Hara N. A cognitive approach to child abuse prevention. J Fam Psychol. 2002;16(3):243–258. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Lewis-Morrarty E, Lindhiem O, Carlson E. Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Dev. 2012;83(2):623–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]