Abstract

Background

Physicians' perspectives regarding hepatitis C shape their approach to patient management. We used utility analysis to evaluate physicians' perceptions of hepatitis C-related health states (HS) and their threshold to recommend treatment.

Methods

A written questionnaire was administered to practicing physicians. They were asked to rate hepatitis C health states on a visual analog scale ranging from 0% (death) to 100% (health without hepatitis C). Physicians then judged quality of life associated with the side effects of antiviral therapy for hepatitis C and indicated the sustained virological response rate that they would require to recommend treatment.

Results

One hundred and thirteen physicians from five states were included. Median utility ratings for hepatitis C health states declined significantly with increasing severity of symptoms: HS1-No Symptoms, No Cirrhosis (88%; 12% reduction from good health), HS2-Mild Symptoms, No Cirrhosis (66%), HS3-Moderate Symptoms, No Cirrhosis (49%), HS4-Mild Symptoms, Cirrhosis (40%), HS5-Severe Symptoms, Cirrhosis (18%) [p < 0.001]. The median rating for life with side effects of antiviral therapy was 47%, suggesting a 53% reduction from good health. That was similar to the utility value for HS3-Moderate Symptoms, No Cirrhosis. The median threshold value for recommending treatment was a sustained response rate of 60%.

Conclusions

1) Physicians' utility ratings for hepatitis C health states were inversely related to the severity of disease manifestations described. 2) Physicians viewed side effects of therapy unfavorably and indicated that on average, they would require a 60% sustained response rate before recommending treatment, which far exceeds the efficacy of current antiviral therapy for hepatitis C in the majority of patients.

Background

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a slowly progressive disease that affects approximately 2.7 million persons in the United States [1]. Most persons with hepatitis C are asymptomatic, although some experience fatigue or other nonspecific symptoms [2,3]. The minority progress to cirrhosis, liver cancer, or liver failure [4-6]. Both physicians and patients must weigh the immediate harm associated with treatment for HCV including side effects and cost of therapy against potential future benefits when making treatment decisions. Interferon and ribavirin cause a number of adverse effects including fatigue, flu-like symptoms, insomnia, depression, cough, and cytopenia [7-9]. The cost of therapy is approximately $1,000 per month with additional charges for laboratory testing and physician's visits. On the other hand, a sustained response to therapy is associated with persistently undetectable HCV RNA, improved liver histology, and gains in health-related quality of life [10-12].

Limited information is available about physicians' perceptions of quality of life with hepatitis C. Physicians' perspectives on HCV and its treatment may influence the advice that they give to their patients about the disease. In the current study, we used utility analysis to evaluate physicians' perspectives about hepatitis C and its therapy. Utility analysis provides a means to quantify preference values about disease states [13,14]. The aims of the study were: 1) to assess whether physicians could provide utilities for hepatitis C health state constructs using visual analog scales, 2) to quantify physicians' judgments about various hepatitis C health states, and 3) to assess physicians' thresholds for recommending treatment.

Methods

Subjects and study instrument

Participants consisted of a convenience sample of 113 physicians from Illinois, Iowa, South Carolina, Indiana, and Michigan. Physicians were surveyed when they attended continuing medical education lectures in Gastroenterology given in 1999. The questionnaire was administered using a paper and pencil format and was completed before the lecture. Demographic information included gender, race, education, and specialty. Participants were asked if they treated patients with Hepatitis C. Five hepatitis C health states (HS) were described ranging from HS1-No Symptoms, No Cirrhosis to HS5-Severe Symptoms, Cirrhosis (Table 1). The descriptions of the hepatitis C health states were developed based on the findings of our previous study of symptoms in patients with HCV [3] and on a consensus of a group of hepatologists experienced in managing patients with hepatitis C. The description of the side effects of treatment was based on published accounts of the adverse effects of interferon and ribavirin [7-9,15].

Table 1.

Descriptions of hepatitis C health states and treatment side effects.

| Health State 1 | ||

| Hepatitis C with No Symptoms, No Cirrhosis | ||

| • | No physical symptoms | |

| • | May transmit to sexual partner | |

| • | May develop cirrhosis | |

| Health State 2 | ||

| Hepatitis C with Mild Symptoms, No Cirrhosis | ||

| • | Sometimes do not feel rested | |

| • | Tire more easily than usual | |

| • | May transmit to sexual partner | |

| • | May develop cirrhosis | |

| Health State 3 | ||

| Hepatitis C with Moderate Symptoms, | ||

| No Cirrhosis | ||

| • | Frequently do not feel rested | |

| • | Tire easily | |

| • | Limited in physical activities | |

| • | May transmit to sexual partner | |

| • | May develop cirrhosis | |

| Health State 4 | ||

| Hepatitis C with Mild Symptoms, Cirrhosis | ||

| • | Sometimes do not feel rested | |

| • | Tire more easily than usual | |

| • | May transmit to sexual partner | |

| • | Have cirrhosis | |

| • | May get liver cancer | |

| • | May get liver failure | |

| Health State 5 | ||

| Hepatitis C with Severe Symptoms, Cirrhosis | ||

| • | Sleep is disturbed | |

| • | Usually feel tired | |

| • | Limited in physical activities including work | |

| • | Little interest in sex | |

| • | Have cirrhosis | |

| • | May get liver cancer | |

| • | May need liver transplant | |

| Treatment Side Effects | ||

| Side Effects of Treatment for Hepatitis C | ||

| • | Needle sticks three times a week | |

| • | Pills twice daily | |

| • | Flu-like symptoms | |

| • | Fever, chills, nausea, headache, poor | |

| appetite | ||

| • | Tend to improve after the first 2 weeks | |

| • | Tiredness, difficulty sleeping, irritability, | |

| difficulty concentrating | ||

| • | Chance of other non-life threatening | |

| medical problems that go away after | ||

| treatment is completed such as low blood | ||

| count, hair loss, and depression | ||

Physicians rated hepatitis C health states using a visual analog scale where 0% represented death and 100% corresponded to life without hepatitis C. We designated life without hepatitis C as the highest preference value and assessed preferences for the health state hepatitis C with No Symptoms, No cirrhosis because the psychological impact of having a disease can effect health status in the absence of physical symptoms. Physicians also rated side effects of antiviral therapy for hepatitis C on a visual analog scale. Finally, participating physicians provided their threshold for recommending antiviral therapy. That is, the sustained virologic response rate that they would require before they would recommend treatment to their patients.

Statistical analysis

Preference values for hepatitis C health states were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate the relationship between categorical demographic variables and physicians' preference values. The relationship between continuous demographic variables and preference values was assessed by the Spearman test. This test also was used to evaluate for an association between preference values for hepatitis C health states, ratings of side effects of antiviral therapy, and treatment threshold.

Results

Demographic data for the participating physicians are presented in Table 2. The majority was primary care physicians (81%), including Internists and Family Practitioners.

Table 2.

Physicians' Demographic Data

| n(%) | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 49 ± 13 | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 85 (75%) | |

| Women | 28 (25%) | |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 73 (66%) | |

| Asian | 31 (28%) | |

| African American | 6 (5%) | |

| Other | 1 (1%) | |

| Degree | ||

| MD | 105 (93%) | |

| DO | 8 (7%) | |

| Specialty | ||

| Internal Medicine | 60 (55%) | |

| Family Practice | 29 (26%) | |

| Gastroenterology | 10 (9%) | |

| Emergency Medicine | 2 (2%) | |

| Other | 9 (8%) | |

| Treat Hepatitis C—yes/no | 25 (22%)/87 (78%) |

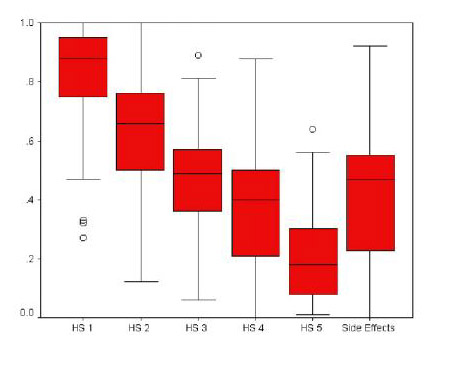

Physicians' preference values for the hepatitis C health states are shown in Figure 1. Utility values decreased as health state severity increased (p < 0.001). The median preference value for HS1-No Symptoms, No Cirrhosis was 88% (interquartile range 75%–95%) corresponding to a 12% reduction from life without hepatitis C. In contrast the median preference value for HS5-Severe Symptoms, Cirrhosis was only 18% (interquartile range 8%–30%).

Figure 1.

Physicians' ratings of the hepatitis C health states and side effects of antiviral therapy. Box plots represent the median, interquartile range, and range. Outlying values are designated with (o). Preference values declined with increasing health state severity.

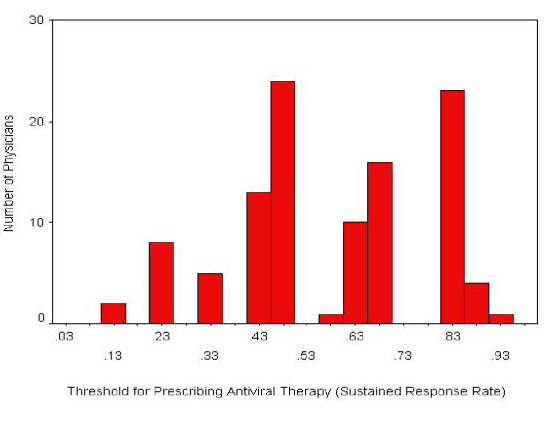

The median preference value for life with the side effects of antiviral therapy was 47% (interquartile range 23%–55%). That is, physicians felt that side effects were associated with a 53% reduction from good health. After considering the HCV health states and the side effects of therapy, physicians indicated that they would require a median of a 60% sustained response rate (interquartile range 40%–80%) before recommending treatment. Only 13% of participating physicians would accept the 30% response rate offered by current antiviral therapy for patients with HCV genotype 1 disease (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of the sustained response rate that participating physicians would require before recommending antiviral therapy to their patients. Median 60% (interquartile range 40–80%).

Health state utility values did not vary significantly with physicians' age, gender, race, specialty or whether they treated hepatitis C. Ratings of side effects and thresholds for recommending treatment were similar across the demographic variables. There were no significant correlations between preference values for hepatitis C health states, ratings of side effects of therapy, and treatment thresholds.

Discussion

In the current study, we developed and evaluated descriptions of hepatitis C health states and side effects of antiviral therapy. We found that physicians understood these descriptions and were able to provide utility assessments using a visual analog scale. Preference values declined significantly with increasing health state severity supporting the validity of the health state constructs.

Physicians felt that hepatitis C causes a dramatic reduction in health status. Even the presence of hepatitis C, without symptoms or cirrhosis (HS 1), was judged to carry a 12% decrement from life without HCV. Our findings parallel those of a study that used the time-trade off method to assess physicians' preference values for health states associated with hepatitis B and HIV [16]. Interestingly, the median preference value for hepatitis C without symptoms in our series was between that provided for HBV without symptoms (92%) and HIV without symptoms (83%) in the previous study [16].

The large range of physicians' rating of treatment side effects (Figure 1) is striking and indicates that doctors' views about the impact of side effects on health status vary substantially. However, the side effects of antiviral therapy were judged severely overall, with a median preference value of 47%. That is, time on therapy was felt to be associated with a 53% reduction from good health. The median preference value for treatment side effects was similar to that provided for HS3-Moderate Symptoms, No Cirrhosis.

On average, physicians indicated that they would require a 60% sustained response before recommending therapy to their patients. The 60% threshold far exceeds the 30% sustained response rate to interferon and ribavirin therapy reported for patients with hepatitis C genotype 1 infection [7,8]. In fact, only 13% of physicians reported a threshold for recommending therapy of 30% or less. The unfavorable assessment of treatment side effects reported by physicians in the current study provides one explanation for relatively low referral rates for hepatitis C among primary care providers. A survey of primary care physicians showed that only 62% refer anti-HCV positive patients with abnormal transaminase levels to sub-specialists [17].

The lack of a significant correlation between the respondents' ratings of treatment side effects and their thresholds for recommending treatment is surprising. We would expect clinicians to make decisions that are consistent with their views on the harm and benefit of a particular therapy. Our data show that a group of physicians, comprised largely of primary care providers, would require a high degree of benefit in terms of response rate to recommend therapy for HCV, which was not necessarily related to their perspectives on the harm associated with treatment side effects. The absence of such a relationship may reflect limited knowledge about hepatitis C and response rates to therapy or preconceived notions about the disease and its treatment. This finding is particularly important because primary care providers often decide whether to refer patients to a sub-specialist. They also educate patients and shape their views about new diagnoses. Continuing education for physicians about the natural history and treatment of hepatitis C is of key importance in helping them to provide optimal advice to their patients.

Advances in antiviral therapy for hepatitis C will affect how physicians and patients view the issue of treatment. Preliminary data suggest that the combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin will increase sustained response rates to more than 50% overall, and to greater than 40% in patients with hepatitis C genotype 1 infection [18]. Hepatologists need to understand other physicians' perspectives on hepatitis C so that they can adequately address their concerns about treatment issues.

Further work is needed to help physicians to understand their patients' views on hepatitis C. A recent study showed that persons with hepatitis C preferred to expedite periods of poor health, implying that they may be more likely to proceed with antiviral therapy and its attendant side effects than to delay treatment [19]. In contrast, the physicians in the current survey had a relatively high threshold for recommending treatment, which would lead them to postpone therapy in the majority of cases. Utility analysis may have a role in facilitating joint decision-making between physicians and patients regarding hepatitis C.

This study does have limitations. We studied a convenience sample of physicians attending continuing medical education lectures. The findings could be biased because we did not collect data on response rates or on the demographic features of physicians who did not complete the survey. Furthermore, although the study population consisted largely of primary care providers, some sub-specialists were included. However, the respondents do represent a cross-section of physicians who may be involved with the diagnosis of hepatitis C.

Conclusions

We have developed and evaluated health state descriptions for hepatitis C. Physicians felt that hepatitis C health states were associated with a substantial decrement in health status. Physicians provided particularly low preference values for side effects of antiviral therapy and high thresholds for recommending treatment. However, ratings of side effects were not significantly correlated with thresholds for recommending therapy, suggesting that additional factors effect physicians views about antiviral therapy. The use of utility analysis could provide a basis for shared decision-making between patients and their physicians about hepatitis C.

List of Abbreviations

HS (health state), HCV (hepatitis C virus), RNA (ribonucleic acid)

Declaration of Competing Interests

None

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1471-230X-1-6-b1.pdf

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Byron Koch Memorial Fund

Contributor Information

Raj Patil, Email: rpatil@ameritech.net.

Scott J Cotler, Email: scotler@rush.edu.

Geraldine Banaad-Omiotek, Email: ginabans@hotmail.com.

Robert A McNutt, Email: Robert_McNutt@rush.edu.

Michael D Brown, Email: mbrowngi@media1.com.

Sheldon Cotler, Email: scotler@condor.depaul.edu.

Donald M Jensen, Email: djensen@rush.edu.

References

- Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:562. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoofnagle JH. Hepatitis C: The clinical spectrum of disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:15S–20S. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotler SJ, Wartelle CF, Larson AM, Gretch DR, Jensen DM, Carithers RL. Pretreatment symptoms and dosing regimen predict side effects of interferon therapy for hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2000;7 doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2000.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyosawa K, Sodeyama T, Tanaka E, Gibo Y, Yoshizawa K, Nakano Y, et al. Interrelationship of blood transfusion, non-A, non-B hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis by detection of antibody to hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 1990;12:671–675. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong MJ, El-Farra NS, Reikes AR, Co RL. Clinical outcomes after transfusion-associated hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1463–1466. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Lancet. 1997;349:825–832. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poynard T, Marcillin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, et al. Randomised trial of interferon alfa 2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alfa 2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. Lancet. 1998;352:1426–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485–1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHutchinson JG, Poynard T. Combination therapy with interferon plus ribavirin for the initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;19:57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkovsky HL, Wooley JM, and the Consensus Interferon Study Group Reduction of health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C and improvement with interferon therapy. Hepatology. 1999;29:264–270. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcellin P, Boyer N, Gervais A, Martinot M, Pouteau M, Castelnau C, et al. Long-term histologic improvement and loss of detectable intrahepatic HCV RNA in patients with chronic hepatitis C and sustained response to interferon-alpha therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:875–881. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-10-199711150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Bayliss MS, Mannocchia M, Davis GL, and the international hepatitis interventional therapy group Health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C: impact of disease and treatment response. Hepatology. 1999;30:550–555. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal: A review. J Health Econ. 1986;5:1–30. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrance GW. Utility approach to measuring health-related quality of life. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:593–600. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Rustigi V, Hoefs J, Gordon SC, Trepo C, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DK, Cardinalli AB, Nease RF. Physicians' assessments of the utility of health states associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Qual Life Res. 1997;6:77–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1026473613487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehab TM, Sonnad SS, Jeffries M, Gunaratum N, Lok ASF. Current practice patterns of primary care physicians in the management of patients with hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1999;30:794–800. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(99)80131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns MP, McHutchinson JG, Gordon S, Rustgi V, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared to interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: 24 week treatment analysis of a multicenter, multinational phase III randomized controlled trial (abstract). Hepatology. 2000;32:297A. [Google Scholar]

- Treadwell JR, Kearney D, Davila M. Health profile preferences of hepatitis C patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:345–350. doi: 10.1023/A:1005420828332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]