Abstract

Regulation of pyruvate fate is an important determinant of anabolic versus catabolic metabolism. A new report in the journal Nature by Kaplon et al. suggests that driving pyruvate oxidation can thwart tumor growth in BRAF-driven melanoma by inducing oncogene-induced senescence, a finding that might be exploited therapeutically.

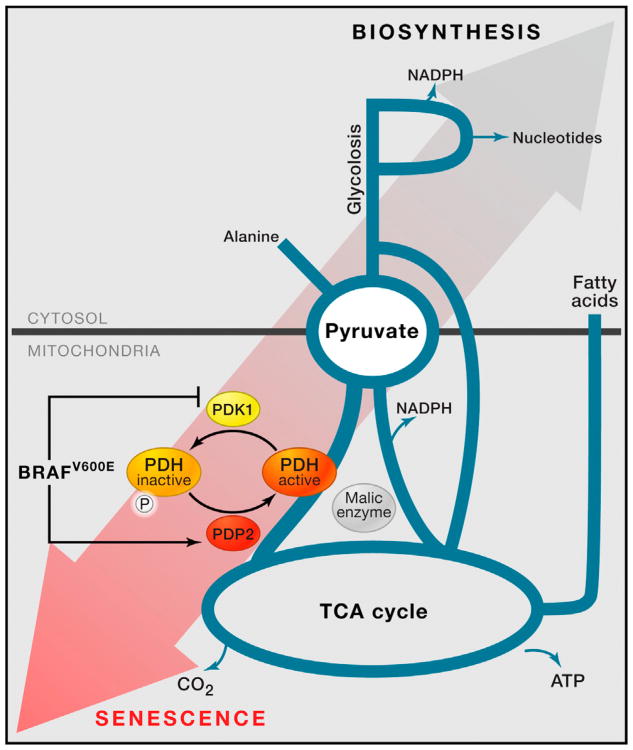

The metabolic fate of pyruvate plays a central role in metabolism that extends beyond the choice between oxidative glucose metabolism in the mitochondria and anaerobic fermentation of glucose in the cytosol. Pyruvate sits at a crossroads of several anabolic and catabolic pathways (Figure 1), and pyruvate metabolism impacts many aspects of cellular biochemistry, including ATP generation, redox status, fuel selection, oxygen consumption, and biomass production. A new study in Nature (Kaplon et al., 2013) suggests that pyruvate metabolism is critically important in the setting of melanoma-associated BRAF mutations. The authors demonstrate that high rates of mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation promote oncogene-induced senescence (OIS), a critical defense against tumor progression.

Figure 1. Pyruvate Is a Critical Hub in the Metabolic Network, Interfacing with Multiple Anabolic and Catabolic Pathways.

A schematic is provided for how pyruvate links to metabolic pathways including the mitochondrial TCA cycle, glycolysis, fatty acid synthesis, nucleotide synthesis, and alanine production. Where malic enzyme lies in relation to pyruvate metabolism is also shown. Kaplon et al. suggest that oncogenic BRAFV600E brings about OIS by inducing PDP2 and suppressing PDK1, which together lessen phosphorylation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH), increase PDH flux, and favor catabolic metabolism. This state is not conducive to cell proliferation.

In the absence of additional cooperating genetic alterations, oncogenic mutations in BRAF cause growth arrest in melanocyte neoplasias (Michaloglou et al., 2005). This phenomenon of OIS is accompanied by distinct phenotypic characteristics and classically involves activation of the p53 or RB signaling pathways (Kuilman et al., 2010). Kaplon et al. studied the metabolic effects of OIS induced by mutant BRAFV600E in human diploid fibroblasts. The authors demonstrated that BRAFV600E-induced senescent cells have increased pyruvate entry into the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle through the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH). PDH flux is regulated by the cell's energetic, nutrient, and redox status and via inhibitory phosphorylation mediated by PDH kinases (Patel and Korotchkina, 2006). Increased PDH activity in the senescent cells was associated with decreased expression of the PDH kinase 1 (PDK1) and increased expression of the PDH phosphatase 2 (PDP2). Together, these transcriptional changes results in less inhibitory phosphorylation of PDH and increased complex activity.

Kaplon et al. provide evidence that altered pyruvate metabolism might be a direct mediator, rather than a consequence, of OIS. By increasing expression of PDK1 or decreasing expression of PDP2, the authors show that activation of PDH activity is required for OIS in the setting of mutant BRAF expression. Forced PDK1 expression in p53−/−;BRAFV600E neonatal melanocytes was found to be sufficient to overcome OIS and promote tumorigenesis. Conversely, knockdown of PDK1 impaired the ability of human melanoma cell lines to form tumors and led to regression of established tumors generated from these cells in immunocompromised mice. Additionally, PDK1 knockdown was found to sensitize BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines to an analog of vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor currently used in patients.

The findings of Kaplon et al. are certain to stoke interest in targeting pyruvate oxidation to treat melanoma. In this regard, dichloroacetate (DCA) has received attention as an inhibitor of PDK and as a potential anticancer agent (Michelakis et al., 2008). If DCA were found to synergize with BRAF inhibitors in a manner similar to PDK1 knockdown, there might be an opportunity for near-term patient benefit. The importance of PDK1 and PDP2, and by extension a role for PDK inhibition, in other models of OIS is less clear. In a model of OIS involving KRASG12V, the authors demonstrated that PDH activity was elevated under senescence conditions, but the change in PDH flux was not due to alterations in PDK1 or PDP2 expression, and large changes in PDH phosphorylation were not observed. Indeed, the regulation of PDH complex activity extends beyond inhibitory phosphorylation, and other mechanisms may limit pyruvate oxidation in non-BRAF-driven tumors. Additionally, the generalizability of increased PDH flux causing senescence in other models might be limited, as senescence has been reported after loss of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor, a condition under which high PDK1 expression and low PDH flux would be expected (Young et al., 2008; Metallo et al., 2011).

The pyruvate “hub” has been suggested as a drug target for treatment of diseases as wide ranging as lactic acidosis, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and cancer (see Roche and Hiromasa, 2007 for review). By driving pyruvate to one fate over another, the entire metabolic landscape of the cell can be affected, in some instances achieving a desirable therapeutic effect. Otto Warburg's observation that proliferating cancer cells do not oxidize all of their pyruvate is illustrative here, as generation of biomass from glucose is impossible if all of the carbon is oxidized to CO2 in the mitochondria. By extension, genetic or pharmacologic manipulations that increase pyruvate oxidation might shuttle glucose carbons away from biosynthesis pathways that are necessary for cell growth and division. Recent work has highlighted the importance of nucleotide metabolism (Aird et al., 2013) and malic enzyme activity (Jiang et al., 2013) in OIS. Whether these pathways are affected by manipulating pyruvate fate to induce OIS remains to be determined, but one could speculate that alterations in pyruvate metabolism might affect NADPH generation through malic enzyme, perhaps limiting DNA synthesis necessary for cell-cycle progression and linking the findings of all three studies.

Cells adopt specific metabolic programs as a response to mutations and environmental cues. Sorting out to what extent changes in metabolism are causal for biological phenomena such as OIS is challenging, particularly as the network effects of specific genetic or pharmacologic manipulations can be difficult to predict and accurately measure. Nonetheless, the findings of Kaplon et al. contribute to the mounting evidence that metabolic programs might be targeted to limit cancer initiation and progression and provide another example of how coordinating flux through anabolic and catabolic pathways is necessary for sustained cell proliferation.

References

- Aird KM, Zhang G, Li H, Tu Z, Bitler BG, Garipov A, Wu H, Wei Z, Wagner SN, Herlyn M, Zhang R. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1252–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Du W, Mancuso A, Wellen KE, Yang X. Nature. 2013;493:689–693. doi: 10.1038/nature11776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplon J, Zheng L, Meissl K, Chaneton B, Selivanov VA, Mackay G, van der Burg SH, Verdegaal EME, Cascante M, Shlomi T, et al. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2463–2479. doi: 10.1101/gad.1971610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Bell EL, Mattaini KR, Yang J, Hiller K, Jewell CM, Johnson ZR, Irvine DJ, Guarente L, et al. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LCW, Soengas MS, Denoyelle C, Kuilman T, van der Horst CMAM, Majoor DM, Shay JW, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Nature. 2005;436:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelakis ED, Webster L, Mackey JR. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:989–994. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MS, Korotchkina LG. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:217–222. doi: 10.1042/BST20060217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche TE, Hiromasa Y. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:830–849. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6380-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AP, Schlisio S, Minamishima YA, Zhang Q, Li L, Grisanzio C, Signoretti S, Kaelin WG., Jr Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:361–369. doi: 10.1038/ncb1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]