Abstract

Mesangial matrix accumulation is an early feature of glomerular pathology in diabetes. Oxidative stress plays a critical role in hyperglycemia-induced glomerular injury. Here, we demonstrate that, in glomerular mesangial cells (MCs), endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is uncoupled upon exposure to high glucose (HG), with enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and decreased production of nitric oxide. Peroxynitrite mediates the effects of HG on eNOS dysfunction. HG upregulates Nox4 protein, and inhibition of Nox4 abrogates the increase in ROS and peroxynitrite generation, as well as the eNOS uncoupling triggered by HG, demonstrating that Nox4 functions upstream from eNOS. Importantly, this pathway contributes to HG-induced MC fibronectin accumulation. Nox4-mediated eNOS dysfunction was confirmed in glomeruli of a rat model of type 1 diabetes. Sestrin 2-dependent AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation attenuates HG-induced MC fibronectin synthesis through blockade of Nox4-dependent ROS and peroxynitrite generation, with subsequent eNOS uncoupling. We also find that HG negatively regulates sestrin 2 and AMPK, thereby promoting Nox4-mediated eNOS dysfunction and increased fibronectin. These data identify a protective function for sestrin 2/AMPK and potential targets for intervention to prevent fibrotic injury in diabetes.

INTRODUCTION

The pathological manifestations of early diabetes in the glomerular microvascular bed include glomerular mesangial cell hypertrophy associated with an increase in mesangial matrix accumulation (1, 2). These events precede the development of irreversible glomerulosclerosis (1, 2). Data from animal models of diabetes, as well as from cultured cells, indicate that hyperglycemia and high glucose (HG) increase extracellular matrix expansion in mesangial cells (MCs) (1, 2).

Oxidative stress with increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has emerged as a critical pathogenic factor in the development of diabetic nephropathy (DN) (1–3). However, the protective effects of traditional antioxidants are very limited. Identifying sources of ROS should help in designing rational therapy to modulate oxidative stress. Although multiple pathways may result in ROS generation, numerous studies identified NADPH oxidases of the Nox family as major sources of ROS in various nonphagocytic/stromal cells, including most kidney cells (4–6). Evidence from studies in cultured cells suggests that the isoform Nox4 is required for the damaging effects of HG that contribute to microvascular complications of diabetes in the retina, the heart, or the kidney (7–13). We have previously reported that Nox4-dependent ROS generation mediates glomerular hypertrophy and mesangial matrix accumulation in early type 1 diabetes (13). In MCs, we showed that Nox4-derived ROS result in the increased fibronectin expression induced by HG (13, 14). Nevertheless, the mechanisms that Nox4 utilizes to exert this biological effect remain unclear, and the upstream regulators or downstream effectors of the oxidase are not well defined.

A major defense against vascular injury is endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which generates nitric oxide (NO) in the presence of optimal concentrations of the substrate l-arginine and the cofactor (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) (15–17). Although the bioavailability of NO varies with the stage of DN, it is now well recognized that progressive nephropathy is associated with a state of NO deficiency due to eNOS dysfunction, a phenomenon referred to as “uncoupling.” Uncoupling of eNOS results not only in decreased bioavailability of NO but also in an increase in the generation of ROS (18–23). The protective role of NO generation by eNOS in the kidney has been conclusively established by recent studies showing that eNOS knockout mice made diabetic (type 1 or type 2) develop advanced lesions and progressive nephropathy (24–26). In addition, eNOS is expressed in MCs and its uncoupling by HG has been linked to the decline in NO levels observed in the diabetic environment (22, 27). However, the mechanisms by which eNOS is inactivated in DN are not clearly identified.

Cells and tissues are endowed with endogenous antioxidant defenses. Sestrin 2 and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), important for the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis, are also stress-inducible proteins that are critical for the suppression of ROS production and protection from oxidative stress (28–33). Sestrin 2 activates AMPK (28–30). The molecular events accounting for the inhibition of ROS generation by sestrin 2 and AMPK are also unclear.

This study identifies the NADPH oxidase Nox4 as a critical mediator of the eNOS uncoupling and decrease in NO bioavailability induced by HG in cultured MCs and in diabetes in vivo. We also demonstrate that ROS derived from dysfunctional eNOS contribute to fibronectin expression in MCs exposed to HG. Furthermore, we establish for the first time that sestrin 2-mediated AMPK activation inhibits the induction of Nox4 and the enhanced ROS production by high glucose and prevents the subsequent eNOS uncoupling, thereby restoring NO levels and attenuating MC fibrotic injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and treatments.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 200 and 225 g were divided into four groups of 4 rats/group. Group 2 was injected intravenously via the tail vein with 55 mg/kg of body weight streptozotocin (STZ) in sodium citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 4.5) to induce diabetes. Group 1 was injected with an equivalent amount of sodium citrate buffer alone. Rats in groups 3 and 4 were injected with STZ followed by phosphorothioated sense (S) or antisense (AS) oligonucleotides for Nox4 (90 ng/g of body weight/day), administered subcutaneously by an Alzet osmotic pump for 14 days (ALZA, Palo Alto, CA) as previously described (12, 13). Oligonucleotides were administered 72 h after STZ injection for 14 days as previously described (12, 13). The blood glucose concentration was monitored 24 h later and periodically thereafter (LifeScan One Touch glucometer; Johnson & Johnson). All rats had unrestricted access to food and water and were maintained in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee procedures.

At day 14, all rats were euthanized, and both kidneys were removed and weighed. Cortical tissue was used for isolation of glomeruli by differential sieving as described previously (13), and samples were frozen for biochemical analyses. Measurement of NADPH oxidase activity was performed on freshly isolated glomeruli.

Antisense oligonucleotides were designed near the ATG start codon of rat Nox4 (5′-AGCTCCTCCAGGACAGCGCC-3′). Antisense and the corresponding sense oligonucleotides were synthesized as phosphorothioated oligonucleotides and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Advanced Nucleic Acid Core Facility, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio).

Note that the animals used here are the same as those used in the experiments presented in the published work from Maalouf et al. (12). Therefore, the table with the blood glucose levels and body weights included in the paper from Maalouf et al. also applies to the present animal studies.

Cell culture, transfections, and adenovirus infection.

Rat glomerular MCs were isolated and characterized as described previously (13). These cells were used between the 15th and 30th passages. Selected experiments were performed in primary and early-passage MCs to confirm the data obtained with late passages. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with antibiotic/antifungal solution and 17% fetal bovine serum.

Transient transfection of MCs with plasmid DNA (1 μg of vector alone or Flag epitope-tagged mammalian expression construct with a truncated form of sestrin 2 [Sesn2F-ΔN] or a construct with a wild-type form of sestrin 2 [Sesn2F]) was performed using GeneJuice transfection reagent (EMD Millipore), as previously described (34). Sesn2F-ΔN and Sesn2F were a generous gift from A. Budanov and M. Karin (University of California San Diego) (29). For the RNA interference experiments, a SMARTpool consisting of four short or small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes specific for rat Nox4 or eNOS was obtained from Dharmacon. The SMARTpool of siRNAs was introduced into the cells by double transfection using X-tremeGENE (Roche Applied Science) as described previously (14, 35). The siRNAs for Nox4 or eNOS were used at a concentration of 100 nM. Scrambled siRNAs (nontargeting siRNA) (100 nM) served as controls to validate the specificity of the siRNAs. Adenovirus encoding wild-type Nox4 (AdWTNox4) was provided by B. J. Goldstein (Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.) (34, 36). Adenovirus encoding a dominant-negative form of the AMPKα2 subunit mutated at lysine 45 (K45R) (AdDN-AMPK) and adenovirus encoding an AMPKγ subunit with a histidine 150 (H150R) mutation that causes constitutive activation of AMPK (AdCA-AMPK) were a generous gift from M. J. Birnbaum (University of Pennsylvania) (37). MCs were infected with adenovirus vectors as previously described (9, 34, 35). As controls for the effects of adenovirus infection alone, an adenovirus encoding green fluorescent protein lacking an insert (AdGFP) or an adenovirus encoding β-galactosidase (AdβGal) was used.

Western blotting. (i) In vivo experiments.

Isolated glomeruli were suspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1% Nonidet P-40) and incubated for 1 h at 4°C (13). After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, protein in the supernatant was determined using the Bio-Rad method.

(ii) In vitro experiments.

MCs grown to near confluence were made quiescent by serum deprivation for 48 h and exposed at 37°C to serum-free DMEM containing 5 mM d-glucose or 25 mM d-glucose for the duration specified below. The cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer at 4°C for 30 min. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein was determined in the cleared supernatant using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent.

For immunoblotting, proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% low-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline and then incubated with a rabbit polyclonal eNOS antibody (dilution 1:1,000) (catalog numbers ADI-KAP-NO020 and KAP-NO002; Enzo Life Sciences/Stressgen), a rabbit monoclonal neuronal NOS (nNOS) antibody (catalog number 2081-1; Abcam/Epitomics, Inc.), a rabbit polyclonal inducible NOS (iNOS) antibody (catalog number 61033; BD Biosciences), a rabbit polyclonal antinitrotyrosine antibody (1:1,000) (catalog number 06-284; EMD Millipore), a rabbit polyclonal Nox4 antibody (1:300) (catalog number H-300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), a rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-AMPKα (Thr172) antibody (1:500) (catalog number 2531; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), a rabbit polyclonal anti-AMPKγ1 antibody (1:500) (catalog number 4187; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), a rabbit polyclonal sestrin 2 antibody (1:500) (catalog number NBP1-4489; Novus Biologicals), a rabbit polyclonal antifibronectin antibody (1:2,500) (catalog number F3648; Sigma), a rabbit polyclonal anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) antibody (1:1,000) (catalog number G9545; Sigma), or a mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (1:4,000) (catalog number A2066; Sigma). The appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were added, and bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Densitometric analysis was performed using NIH Image software (14, 35).

Assay of eNOS dimer/monomer.

SDS-resistant eNOS dimers and monomers were assayed by using low-temperature SDS-PAGE as described previously (38). Briefly, after being washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, d-glucose-treated MCs were lysed as described above, and protein lysates were mixed with loading buffer and loaded on gels without boiling. Proteins were separated with low-temperature SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions (with β-mercaptoethanol). Gels and buffers were kept at 4°C during the whole procedure.

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy.

MCs grown on 4-well chamber slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min. The cells were then blocked with 5% normal goat serum or 5% normal donkey serum in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min and incubated with the appropriate primary antibody (anti-eNOS, anti-3-nitrotyrosine, antifibronectin, or anti-sestrin 2 antibody) for 30 min. Cyanin-3- or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies were then applied to the appropriate cells for 30 min. The cells were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline, mounted with antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and visualized on an Olympus FV-500 confocal laser scanning microscope. To estimate the brightness intensities of the 3-nitrotyrosine, fibronectin, and sestrin 2 signals, groups of cells randomly selected from the digital image were outlined (at least five groups for each sample), and the average brightness of the enclosed area was semiquantified using either Image-Pro Plus 4.5 software (Media Cybernetics) or NIH Image/ImageJ software, as described previously (13, 14, 35). The data shown represent three separate experiments and are expressed as relative fluorescence intensities.

NADPH oxidase assay.

NADPH oxidase activity was measured by the lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence method as described previously (13, 14).

(i) Glomeruli.

NADPH oxidase activities in glomeruli were measured as previously described (13). Homogenates from isolated glomeruli were prepared in 1 ml and 500 μl, respectively, of lysis buffer (20 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.0, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin) by using a Dounce homogenizer (100 strokes on ice). Homogenates were subjected to a low-speed centrifugation at 800 × g, 4°C, for 10 min to remove the unbroken cells and debris, and aliquots were used immediately. To start the assay, 100-μl amounts of homogenates were added to 900 μl of 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 1 mM EGTA, 150 mM sucrose, 5 μM lucigenin, and 100 μM NADPH. Photon emission in terms of relative light units was measured every 20 or 30 s for 10 min in a luminometer. There was no measurable activity in the absence of NADPH. A buffer blank (less than 5% of the cell signal) was subtracted from each reading. Superoxide production was expressed as relative chemiluminescence (light) units (RLU)/mg protein. Protein content was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent.

(ii) Cultured mesangial cells.

NADPH oxidase activities in cells were measured as described previously (13, 14). Briefly, MCs grown in serum-free medium containing 5 or 25 mM glucose were washed five times in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and were scraped from the plate in the same solution, followed by centrifugation at 800 × g, 4°C, for 10 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer. Cell suspensions were homogenized with 100 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer on ice. Aliquots of the homogenates were used immediately to measure NADPH-dependent superoxide generation as described above.

Detection of ROS production. (i) Detection of intracellular superoxide in MCs using HPLC.

Cellular superoxide production in MCs was assessed by HPLC analysis of dihydroethidium (DHE)-derived oxidation products, as described previously (39). The HPLC-based assay allowed the separation of the superoxide-specific 2-hydroxyethidium (EOH) from the nonspecific ethidium. Briefly, after exposure of quiescent MCs grown in 60-mm dishes to 5 mM or 25 mM d-glucose for the durations indicated below, cells were washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS)-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) and incubated for 30 min with 50 μM DHE (Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS–100 μM DTPA. Note that for prolonged treatment, cells were first stimulated with d-glucose and then incubated with DHE. Cells were harvested in acetonitrile and centrifuged (12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C). The homogenate was dried under vacuum and analyzed by HPLC with fluorescence detectors (Jasco HPLC system, LC-2000 plus series). Quantification of DHE, EOH, and ethidium concentrations was performed by comparison of integrated peak areas between the obtained and standard curves of each product under chromatographic conditions identical to those described above. EOH and ethidium were monitored by fluorescence detection with excitation at 510 nm and emission at 595 nm, whereas DHE was monitored by UV absorption at 370 nm. The results are expressed as the amount of EOH produced (nmol) normalized for the amount of DHE consumed (i.e., initial minus remaining DHE in the sample; μmol).

(ii) Detection of intracellular ROS in MCs.

ROS generation was also assessed in live cells with DHE (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) as previously described (40). Cells were loaded with 10 μM DHE in phenol-free DMEM for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed with warm buffer. DHE fluorescent intensity was determined at 520-nm excitation and 610-nm emission and visualized on an Olympus FV-500 confocal laser scanning microscope. The brightness intensity of the DHE signal was semiquantified by using either Image-Pro Plus 4.5 software (Media Cybernetics) or NIH Image/ImageJ software as described previously (14, 35). The data shown represent three separate experiments and are expressed as relative fluorescence intensities.

Alternatively, DHE-derived fluorescence was followed in a multiwell fluorescence plate reader. MCs were grown in 12- or 24-well plates and serum deprived for 48 h. Immediately before the experiments, cells were washed with phenol red-free DMEM and loaded with 10 μM DHE (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) dissolved in phenol-free DMEM solution for 15 min at 37°C. They were then incubated with 5 mM or 25 mM d-glucose for various time periods. Subsequently, DHE fluorescence was detected at excitation and emission wavelengths of 560 and 635 nm, respectively, and measured with a multiwell fluorescence plate reader (Chameleon multilabel detection platform; Bioscan).

(iii) Detection of ROS production in isolated glomeruli.

ROS production in isolated glomeruli was detected by DHE fluorescence as described previously (19). Isolated glomeruli from each group of animals were incubated in phenol-free DMEM containing 10 μM DHE (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 37°C. After being washed with phenol-free DMEM, the glomeruli were placed in cover glass chambers. The fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 520 nm and an emission wavelength of 610 nm using confocal laser-scanning microscopy.

Assay of cGMP/nitric oxide bioactivity.

The intracellular cyclic GMP (cGMP) contents were determined in serum-starved MCs (exposed to 5 mM or 25 mM d-glucose for the durations indicated below) or in glomeruli using an enzyme-linked immunoassay colorimetric kit from Enzo Life Sciences/BIOMOL (direct cGMP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] kit, catalog number ADI-900-014) according to the manufacturer's instructions. MCs or glomeruli were lysed in 0.1 M HCl and then analyzed directly in a microtiter plate.

Assay of nitric oxide synthase activities.

The nitric oxide-synthesizing activities of NOS were measured with the NOSdetect assay kit (Stratagene) as described previously (41, 42). Briefly, the conversion of l-[14C]arginine (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) to l-[14C]citrulline was used to determine NOS activity in MC lysates with the addition of the appropriate cofactors according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Nonspecific production of l-citrulline was monitored by performing the reaction in the presence of L-NAME (NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester), a NOS inhibitor. In the presence of L-NAME, no significant production of NO was observed. Activity is expressed as pmol citrulline/min/mg protein.

Detection of 3-nitrotyrosine.

3-Nitrotyrosine cellular levels were determined in serum-starved MCs treated with 5 mM or 25 mM d-glucose for the durations indicated below by using an enzyme immunoassay kit from OxisResearch Products/Percipio Biosciences, Inc. (Biooxytech nitrotyrosine-EIA assay, catalog number 21055) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± standard errors (SE). Statistical significance was assessed by Student's unpaired t test. Significance was determined as a probability (P value) of less than 0.05.

RESULTS

eNOS is uncoupled upon exposure of MCs to high glucose and is a source of ROS.

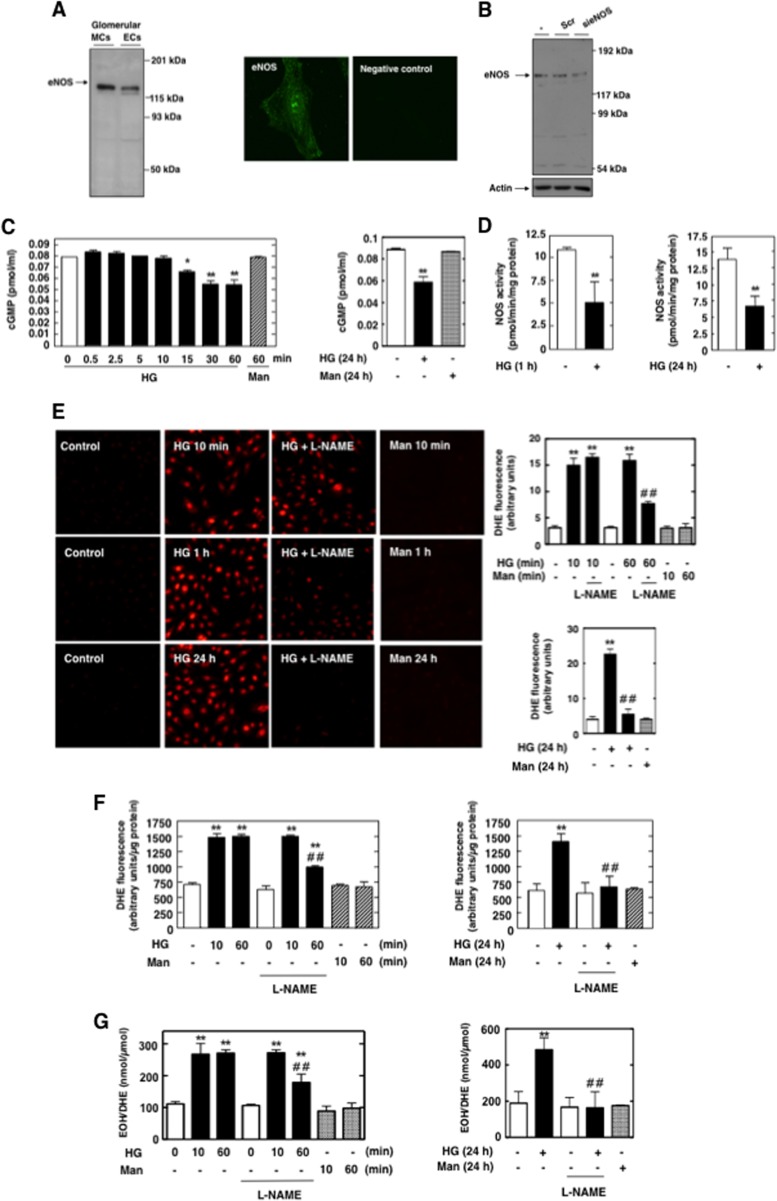

We first confirmed that eNOS protein was highly expressed not only in glomerular endothelial cells (ECs) but also in MCs (Fig. 1A, left). eNOS expression was also detected by immunofluorescence (Fig. 1A, right). Importantly, the eNOS protein band expression was markedly decreased after transfection of MCs with small interfering RNA oligonucleotides (siRNA) specific for eNOS (sieNOS) but not nontargeting siRNA (Scr), thereby confirming its identity (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

NOS is uncoupled upon stimulation with HG and contributes to HG-induced superoxide generation in MCs. (A) Left, immunoblot detection using anti-eNOS antibodies shows a 130- to 145-kDa band corresponding to the predicted molecular mass of the enzyme in glomerular ECs and MCs. Right, immunofluorescence confocal microscopy using eNOS antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-linked secondary antibodies showing eNOS distribution in MCs. (B) MCs were untransfected (−) and transfected with control nontargeting siRNA (Scr; 100 nM) or with siRNA for eNOS (sieNOS; 100 nM), and eNOS protein expression was determined by Western blotting. Transfection of MCs with sieNOS but not Scr reduced the 130- to 145-kDa band. (C) Treatment of serum-deprived rat MCs with HG for short (left) or prolonged (right) time periods caused decreases in cGMP synthesis, an indicator of NO bioactivity. Mannitol (Man) (20 mM mannitol plus 5 mM d-glucose) was used as an osmotic control. Values are the means ± SE of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 versus control; **, P < 0.01 versus control. (D) Treatment of serum-deprived rat MCs with HG for 1 h or 24 h caused decreased NOS activity. NOS activity was measured in MC lysate by monitoring the formation of l-[14C]citrulline from l-[14C]arginine. Activity is expressed as pmol citrulline/min/mg protein. Values are the means ± SE of three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control. (E, F, and G) Serum-deprived MCs were preincubated with the NOS inhibitor L-NAME (100 μM, 3 h) before treatment with 25 mM HG for 10 min, 1 h, or 24 h. Mannitol (Man) (20 mM mannitol plus 5 mM d-glucose) was used as osmotic control. Superoxide generation was evaluated using DHE (10 μM, 30 min) and confocal microscopy (E), DHE and a multiwell fluorescence plate reader (F), or DHE and HPLC (G) as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Right, relative levels of DHE fluorescence (arbitrary units) were semiquantified. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control; ##, P < 0.01 versus HG.

Under pathological conditions, eNOS dysfunction or uncoupling resulted in decreased bioavailability of NO and increased generation of superoxide anion by the enzyme (16, 17, 19, 22, 38, 43). We assessed the temporal effects of HG on NO formation and intracellular superoxide generation. Exposure of MCs to HG (25 mM d-glucose) decreased cGMP production, an indicator of NO bioactivity. The inhibition of NO bioavailibility by HG is maximal at 30 to 60 min and persists for 24 h (Fig. 1C). To determine the mechanism involved, we assayed the activity of NOS in MC lysates by monitoring the conversion of radiolabeled l-arginine to l-citrulline, which is formed stoichiometrically with NO and yields information on the capacity of NOS to make NO. Consistent with the cGMP findings, NOS activities were significantly reduced in MCs exposed to 25 mM HG for 1 h and 24 h compared with the NOS activities in cells incubated with a normal glucose concentration (NG, 5 mM d-glucose) (Fig. 1D). These data confirm that NOS generates a smaller amount of NO upon stimulation with HG, resulting in diminished NO bioavailibility.

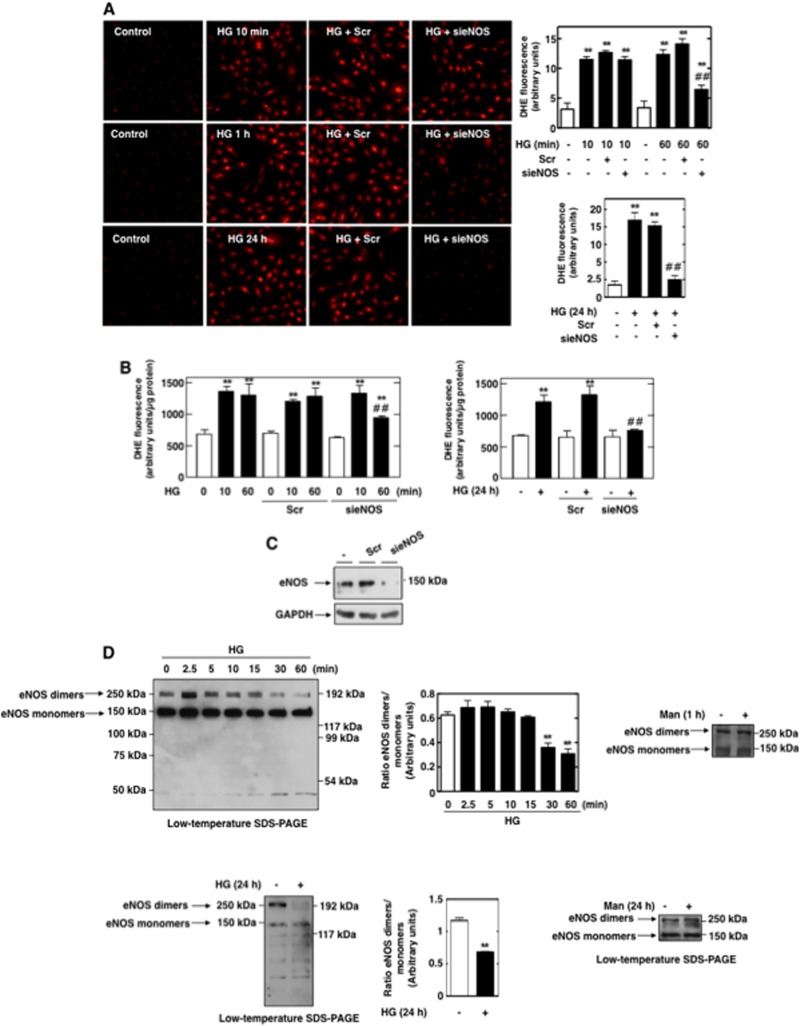

The time-based effects of HG on intracellular superoxide generation were also examined in parallel using DHE (10 μM, 30 min) and confocal microscopy, a multiwell fluorescence plate reader, or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The contribution of uncoupled NOS to ROS production was determined by measuring superoxide generation in the presence and absence of the NOS inhibitor L-NAME (NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester) or eNOS siRNA. Inhibition of HG-induced superoxide generation by L-NAME or siRNA for eNOS (sieNOS) is an indicator that eNOS is a source of ROS and, therefore, that the enzyme is uncoupled. The data showed that the intracellular superoxide generated by exposure of MCs to HG for 1 h or 24 h was attenuated by L-NAME (Fig. 1E to G). These results demonstrate that during these time periods, NOS contributed to HG-induced oxidative stress. Downregulation of eNOS protein expression by specific siRNA significantly inhibited HG-induced superoxide generation in MCs and mimicked the effects of L-NAME (Fig. 2A and B). The results shown in Fig. 2C confirmed the effective knockdown of eNOS protein by the siRNAs. HPLC analysis of the superoxide-specific product of DHE, 2-hydroxy-ethidium (EOH), validated the specificity of superoxide measurements with DHE.

Fig 2.

Uncoupled eNOS contributes to HG-induced superoxide generation in MCs. (A and B) MCs were untransfected or transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Scr) or eNOS siRNA (sieNOS) and exposed to 25 mM glucose (HG) for 10 min, 1 h, or 24 h. Superoxide generation was evaluated using DHE (10 μM, 30 min) and confocal microscopy (A) or DHE and a multiwell fluorescence plate reader (B) as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Right, relative levels of DHE fluorescence (arbitrary units) were semiquantified. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control; ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in untransfected cells. (C) MCs were untransfected (−) or transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Scr) or siRNA for eNOS (sieNOS). eNOS protein knockdown with sieNOS but not Scr was confirmed by Western blotting. (D) HG decreased the eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratio, a reflection of the disruption of eNOS dimer stability and eNOS uncoupling. Serum-deprived MCs were exposed to 25 mM glucose (HG) for the indicated times, and samples were subjected to low-temperature SDS-PAGE. Mannitol (Man) (20 mM mannitol plus 5 mM d-glucose) was used as osmotic control. The Western blots shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. Middle panels show ratios of the intensities of eNOS dimer bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of eNOS monomer bands. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control.

Because eNOS dimer formation and stability are critical for eNOS to functionally produce NO, a decrease in the dimer-to-monomer ratio reflects eNOS uncoupling. Therefore, the proportions of eNOS existing as either dimers or monomers in MCs treated with HG were determined. Electrophoresis of MC lysates without prior heat denaturation (low-temperature SDS-PAGE) revealed bands approximately twice the size of the eNOS monomer, attributable to the eNOS dimer. Exposure of the cells to HG for 1 h or 24 h demonstrated a significant reduction in the dimer-to-monomer ratio compared with the ratio in the control (Fig. 2D). Importantly, the decrease in dimers started at 15 to 30 min and was maximal at 1 h (Fig. 2D), time periods when we showed that the superoxide generated by HG is mediated by uncoupled NOS and that NO production is decreased.

Incubation of MCs with the osmotic control, mannitol (20 mM), had no effect on NO bioavailability, superoxide generation, or eNOS dimer stability (Fig. 1 and 2).

The other isoforms of NOS (neuronal and inducible) are expressed in the kidney (44). Since they also are susceptible to uncoupling (43), their role was considered. We found that iNOS and nNOS protein are not expressed in MCs under basal conditions. Treatment of the cells with HG for short or prolonged time periods did not induce the expression of iNOS or nNOS protein (data not shown), indicating that iNOS and nNOS are not directly implicated in the effects of HG in MCs. This is consistent with published data showing that nNOS is not expressed in rat MCs that are either untreated or exposed to HG (27).

Collectively, these findings indicated that uncoupled eNOS was a source of ROS in MCs exposed to HG and provide a rationale for studying the mechanism(s) by which the enzyme is uncoupled in these cells. Interestingly, the data also showed that, in the early phase (within 10 min), the superoxide generated in response to HG was not derived from uncoupled NOS (insensitive to L-NAME/eNOS siRNA), while at 60 min, superoxide production was decreased in the presence of L-NAME/eNOS siRNA (Fig. 1E to G and 2A and B), implicating dysfunctional NOS in superoxide generation. Note also that at 60 min, the inhibition of ROS generation was only partial with agents targeting NOS, indicating that another source contributed to the oxidative stress. In the late phase (24 h), eNOS appeared to be the predominant source of superoxide, as L-NAME/eNOS siRNA nearly abolished HG-dependent superoxide production.

Uncoupled eNOS is required for the expression of fibronectin in response to high glucose.

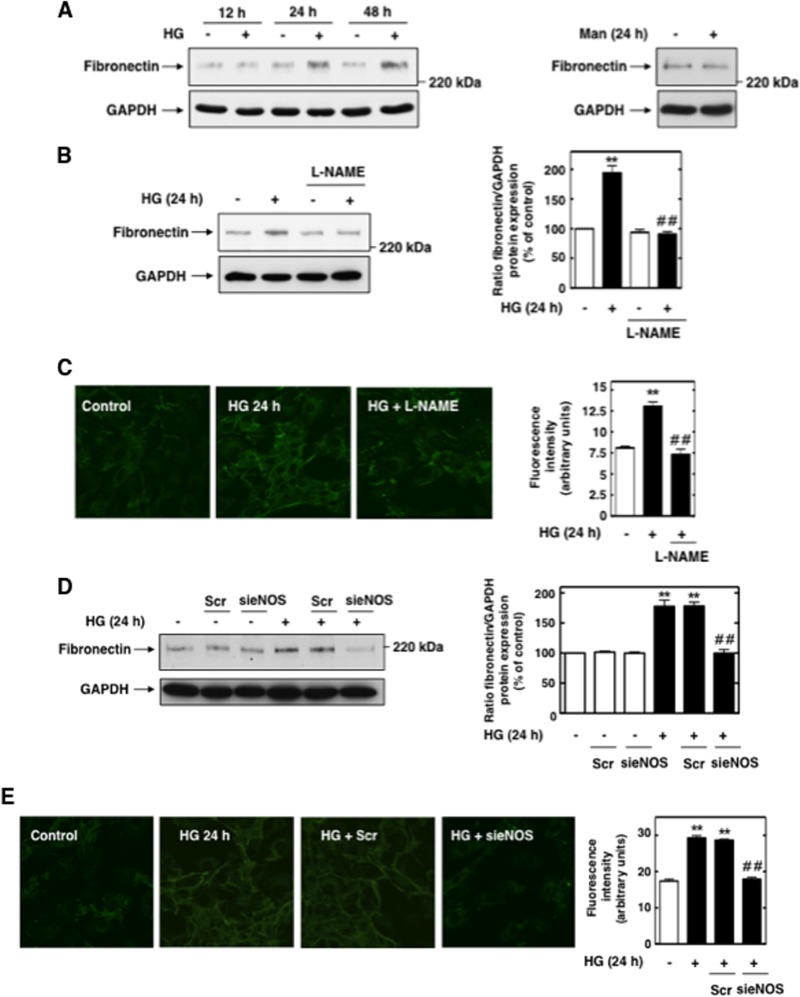

We then assessed the biological consequences of eNOS dysfunction and determined its role in the abnormal matrix accumulation by MCs. Fibronectin accumulation was studied after prolonged exposure to HG. Kinetic studies showed that HG effectively induced fibronectin protein expression at 24 h and 48 h (Fig. 3A). Incubation of MCs with the osmotic control, mannitol (20 mM), had no effect on fibronectin expression.

Fig 3.

Uncoupled eNOS contributes to HG-induced fibronectin accumulation in MCs. (A) Serum-deprived MCs were exposed to HG (25 mM) for 12, 24, and 48 h, and fibronectin accumulation was evaluated by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as loading control, and mannitol (Man) (20 mM mannitol plus 5 mM d-glucose) as osmotic control. (B and C) Serum-deprived MCs were preincubated with the NOS inhibitor L-NAME (100 μM, 3 h) before treatment with HG (25 mM) for 24 h, and fibronectin deposition was evaluated by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (B) or by immunofluorescence with confocal microscopy (C). (D and E) MCs were untransfected or transfected with 100 nM nontargeting siRNA (Scr) or eNOS siRNA (sieNOS) and exposed or not to HG (25 mM) for 24 h. Fibronectin protein expression was determined by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (D) or by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy (E). (B and D) Right, histograms represent the ratios of the intensities of fibronectin bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of GAPDH bands. The data are expressed as percentages of the control (untreated or untransfected cells), where the ratio in the control was defined as 100%. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. (C and E) Right, semiquantification of fluorescence intensities. The photomicrographs are representative of three individual experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control; ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in untreated or untransfected cells.

In order to establish the link between uncoupled NOS and the fibrotic response of MCs to HG, we examined the effect of L-NAME or sieNOS on HG-mediated fibronectin protein expression by Western blotting and immunofluorescence analyses. Treatment of MCs with L-NAME or transfection of the cells with sieNOS but not nontargeting siRNA prevented the increase in fibronectin caused by prolonged exposure of MCs to HG (Fig. 3B to E). These data support a role for dysfunctional eNOS in the redox-sensitive signaling cascade triggered by HG and leading to extracellular matrix protein production in MCs.

Peroxynitrite is required for eNOS uncoupling and the expression of fibronectin in response to high glucose.

Peroxynitrite, the product of NO-superoxide interaction, is known as a powerful promoter of eNOS uncoupling via oxidative modification of the enzyme (15–17, 38). Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that peroxynitrite is implicated in HG-mediated eNOS dysfunction in MCs. HG elicited a rapid increase in 3-nitrotyrosine, a footprint of peroxynitrite production, at 10 min and 60 min as assessed by ELISA (Fig. 4A) and immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 4B). Incubation of MCs with the osmotic control, mannitol (20 mM), had no effect on 3-nitrotyrosine levels. Peroxynitrite formation preceded eNOS dysfunction (which takes place at 60 min), suggesting that peroxynitrite was critical to eNOS uncoupling.

Fig 4.

Peroxynitrite is required for eNOS uncoupling and the expression of fibronectin in response to high glucose. (A and B) HG causes a rapid increase in 3-nitrotyrosine, a footprint of peroxynitrite generation. Serum-deprived MCs were treated with 25 mM glucose (HG) for 10 min or 1 h, and 3-nitrotyrosine levels were assessed using an enzyme immunoassay kit (A) or immunofluorescence and confocal laser microscopy (B). Mannitol (Man) (20 mM mannitol plus 5 mM d-glucose) was used as osmotic control. (B) Histogram represents the semiquantification of fluorescence intensities. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control. (C) Serum-deprived MCs were pretreated with uric acid (200 μM, 3 h), a peroxynitrite scavenger, or L-NAME (100 μM, 3 h) before exposure to HG for 10 min or 1 h, and 3-nitrotyrosine was evaluated by immunofluorescence staining. Right, semiquantification of fluorescence intensities. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control; ##, P < 0.01 versus HG. (D) Serum-deprived MCs were pretreated with uric acid (200 μM, 3 h) before exposure to HG for 1 h or 24 h, and NO bioactivity was assessed by measuring cGMP synthesis. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control. (E) Serum-deprived MCs were pretreated with uric acid (200 μM, 3 h) before exposure to HG for 1 h or 24 h, and eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios were determined by low-temperature SDS-PAGE. Bottom, ratios of the intensities of eNOS dimer bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of eNOS monomer bands. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control. (F) Serum-deprived MCs were pretreated with uric acid (200 μM, 3 h) before exposure to HG for 24 h, and fibronectin protein expression was determined by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates. Bottom, histogram represents the ratios of the intensities of fibronectin bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of GAPDH bands. The data are expressed as described in the legend to Fig. 3B and D. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control; ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in untreated cells.

Pretreatment of the cells with the peroxynitrite scavenger uric acid markedly attenuated HG-induced 3-nitrotyrosine staining, indicating that the signal detected corresponded to peroxynitrite formation (Fig. 4C). Moreover, incubation of MCs with L-NAME also significantly inhibited the increment in 3-nitrotyrosine staining observed after exposure of the cells to HG for 10 and 60 min (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that NOS participated in peroxynitrite production, most likely via providing the necessary NO. The contribution of peroxynitrite to eNOS dysfunction was clearly ascertained by the findings that preincubation of MCs with uric acid drastically blocked the HG-mediated decrease in NO production (Fig. 4D) and eNOS dimer stability (Fig. 4E) during the time periods for which eNOS was uncoupled (1 h and 24 h). As shown by the results in Fig. 4F, scavenging of peroxynitrite with uric acid also inhibited HG-induced fibronectin accumulation in MCs.

Taken together, these findings identified peroxynitrite as a critical mediator of eNOS uncoupling and the subsequent MC matrix protein accumulation in response to HG.

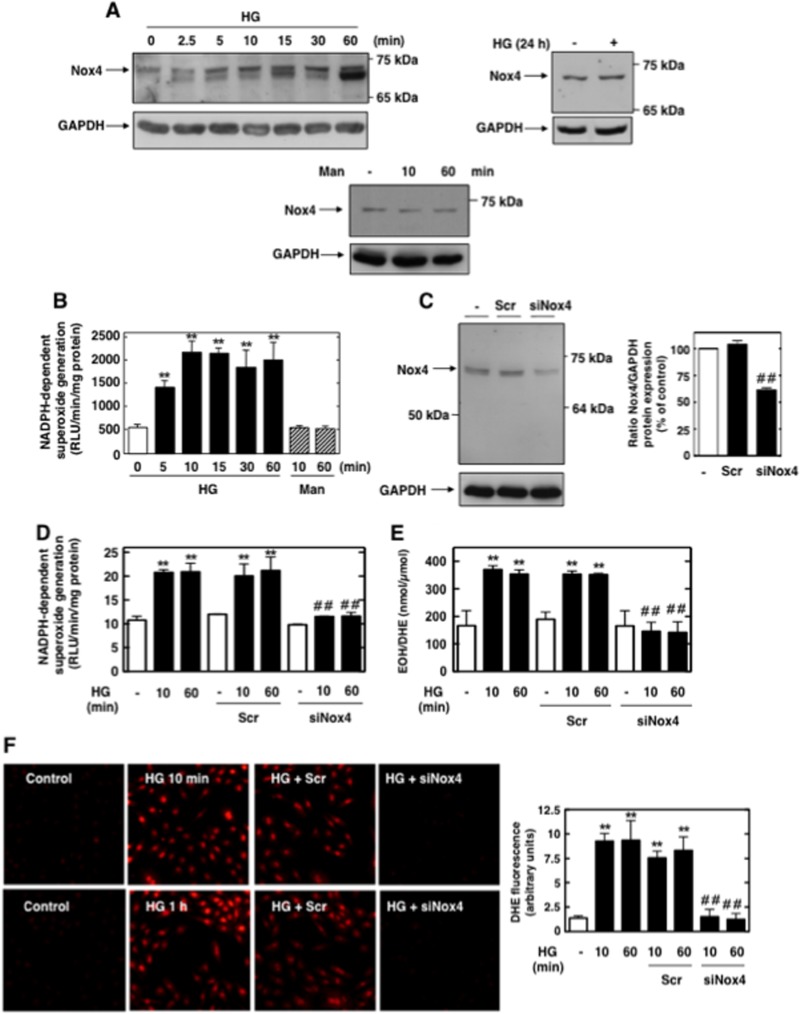

Nox4 mediates the high-glucose-induced early increase in superoxide generation.

In MCs, HG caused an early and sustained time-dependent increase in Nox4 protein expression and NADPH-dependent superoxide generation beginning at 5 min and continuing up to 60 min (Fig. 5A and B). Since Nox4 is known to be constitutively active, upregulation of its protein levels directly accounted for the increased NADPH oxidase activity, particularly at the early time points where the contribution by eNOS was negligible. Prolonged exposure of MCs to HG (24 h) did not alter Nox4 protein levels (Fig. 5A). Incubation of MCs with the osmotic control, mannitol (20 mM), had no effect on Nox4 expression and NADPH oxidase activity.

Fig 5.

Nox4 is upregulated by HG and mediates HG-induced acute ROS production in MCs. (A) Serum-starved MCs were treated for the indicated times with HG (25 mM), and Nox4 protein expression was evaluated by Western blotting. Mannitol (Man) (20 mM mannitol plus 5 mM d-glucose) was used as osmotic control. (B) Serum-starved MCs were stimulated with HG (25 mM) for the indicated time periods, and NADPH-dependent superoxide generation in MC homogenates was measured by the lucigenin (5 μM)-enhanced chemiluminescence method. The initial rates of enzyme activity were calculated and expressed as relative chemiluminescence (light) units (RLU)/min/mg protein as described in Materials and Methods. Mannitol (Man) (20 mM mannitol plus 5 mM d-glucose) was used as osmotic control. Values are the means ± SE of three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control. (C) MCs were untransfected (−) or transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Scr) or siRNA for Nox4 (siNox4). Nox4 protein knockdown with siNox4 but not Scr was confirmed by Western blotting. Right, histogram represents the ratios of the intensities of Nox4 bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of GAPDH bands. The data are expressed as percentages of control, where the ratio in the control was defined as 100%. **, P < 0.01 versus control; ##, P < 0.01 versus untransfected cells. (D, E, and F) MCs were untransfected or transfected with nontargeting siRNA (Scr) or siNox4 and exposed or not to HG (25 mM) for 10 min or 1 h. ROS generation was then assessed by measuring NADPH oxidase activities in MC homogenates (D) and DHE fluorescence with HPLC (E) or confocal microscopy (F). (F) Right, semiquantification of fluorescence intensities. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control; ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in untransfected cells.

In order to directly establish that Nox4 is necessary for HG-induced ROS production, Nox4 expression was downregulated with specific siRNAs. Transfection of siRNA for Nox4 (siNox4) but not nontargeting siRNA (Scr) reduced Nox4 protein abundance (Fig. 5C). Importantly, siNox4 nearly abrogated the HG-dependent increase in NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 5D) and intracellular superoxide generation as assessed by DHE/HPLC or DHE/confocal microscopy (Fig. 5E and F). Importantly, the data showed that, in the early phase (within 10 min), the superoxide generated in response to HG was most likely derived from Nox4 but not NOS, whereas at a later time point (60 min), both NOS and Nox4 contributed to superoxide generation. The absence of an effect of HG on Nox4 protein expression at 24 h was consistent with the observation that, at this time point, uncoupled eNOS was the predominant source of ROS (Fig. 1 and 2).

These findings indicated that, under HG conditions, the production of ROS via Nox4 preceded eNOS uncoupling and support the idea that Nox4-derived superoxide anions act as kindling radicals that interact with NO to initiate peroxynitrite formation and the consequent eNOS uncoupling.

Nox4 is required for the high-glucose-induced early increase in peroxynitrite generation and eNOS dysfunction in MCs.

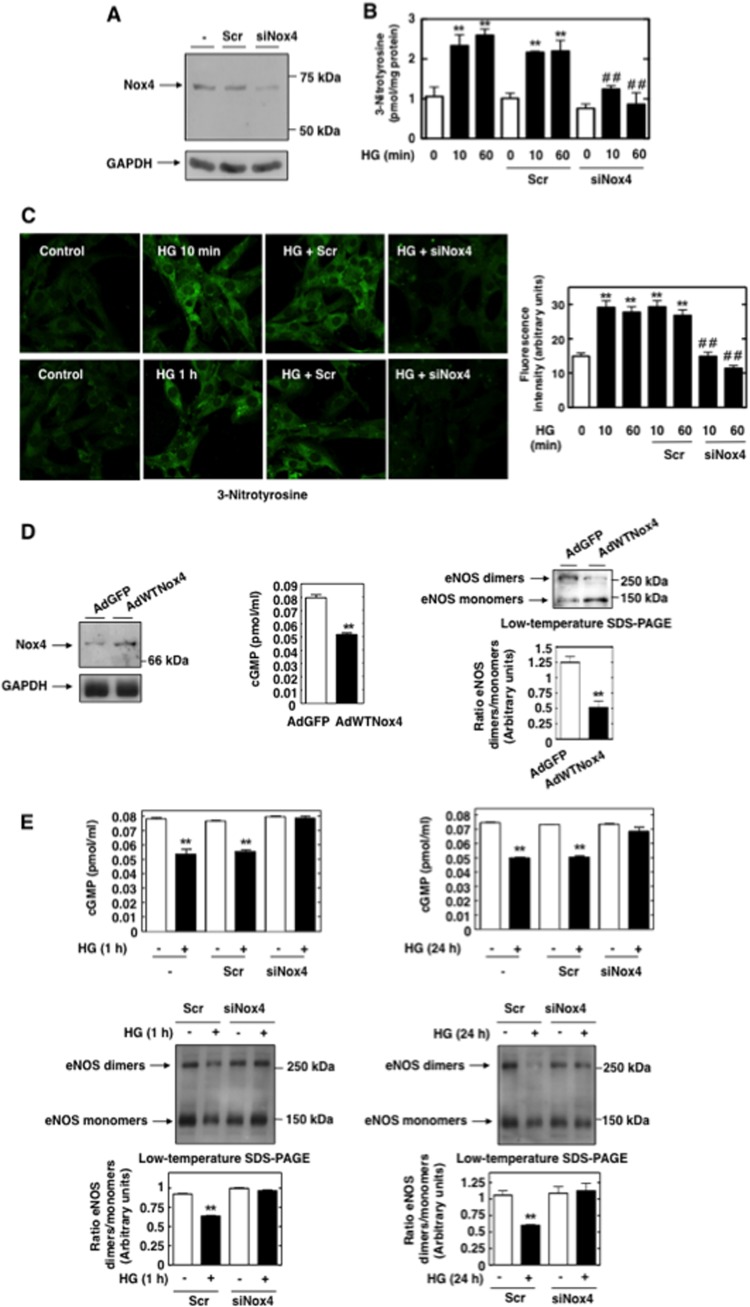

NADPH oxidases of the Nox family constitute an important source of superoxide that contributes to the formation of peroxynitrite, initiating eNOS dysfunction (16, 17). To test the hypothesis that ROS generated by Nox4 play the role of kindling oxidants, the consequences of siRNA-mediated Nox4 protein knockdown on peroxynitrite formation were determined in MCs exposed to HG for short periods (10 and 60 min). Effective downregulation of Nox4 protein by siRNA in MCs was confirmed by the results shown in Fig. 6A. Impairment of Nox4 function with siRNA nearly abrogated the HG-induced increase in 3-nitrotyrosine, demonstrating that Nox4 is required for peroxynitrite generation (Fig. 6B and C). These findings indicated that Nox4-derived superoxide is at the origin of the peroxynitrite formation that, in turn, triggers eNOS dysfunction in the presence of HG.

Fig 6.

Nox4 mediates HG-induced early increase in peroxynitrite generation and eNOS dysfunction in MCs. (A) MCs were untransfected or transfected with nontargeting Scr or with siRNA for Nox4 (siNox4), and Nox4 protein expression was determined by Western blotting. (B and C) Serum-deprived MCs transfected with Scr or siNox4 were treated with or without HG (25 mM) for 10 min or 1 h, and 3-nitrotyrosine was assessed with an enzyme immunoassay kit (B) and immunofluorescence with confocal laser microscopy (C). (C) Right, semiquantification of fluorescence intensities. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control. ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in untransfected cells. (D) MCs were infected with AdGFP or virus expressing wild type Nox4 (AdWTNox4), and levels of cGMP synthesis (middle) or eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios (right) were determined. Left, immunoblotting with Nox4 antibody confirmed the overexpression of the oxidase from the adenovirus vector. **, P < 0.01 versus GFP vector-transfected cells. (E) Top and middle, serum-deprived MCs untransfected or transfected with Scr or siNox4 were treated with or without HG (25 mM) for 1 h or 24 h, and levels of cGMP synthesis or eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios were assessed. Bottom, ratios of the intensities of eNOS dimer bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of eNOS monomer bands. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control.

Next, we established the direct involvement of Nox4 oxidase in eNOS dysfunction and decrease in NO bioavailability. The introduction of adenovirus encoding wild-type active Nox4 (AdWTNox4) in MCs cultured in normal glucose mimicked the effect of HG, resulting in eNOS dimer dissociation and a significant decrease in NO-mediated cGMP production (Fig. 6D). Adenovirus encoding green fluorescent protein (AdGFP) was used as a control. The link between Nox4 and the decrease in NO availability or eNOS dysfunction was further demonstrated by the observation that blockade of Nox4 with specific siRNA but not nontargeting siRNA restored the levels of NO and prevented eNOS dimer disruption in cells treated with HG for 1 h or 24 h (the time points where eNOS is uncoupled) (Fig. 6E). The data clearly identify Nox4 as a pivotal mediator of eNOS dysfunction and decreased NO bioavailability in MCs.

These data indicate that Nox4-derived superoxide interacts with NO generated constitutively by coupled eNOS, resulting in the formation of peroxynitrite that subsequently uncouples and alters eNOS function.

Nox4-derived ROS mediate the diabetes-induced decrease in nitric oxide bioavailability in glomeruli.

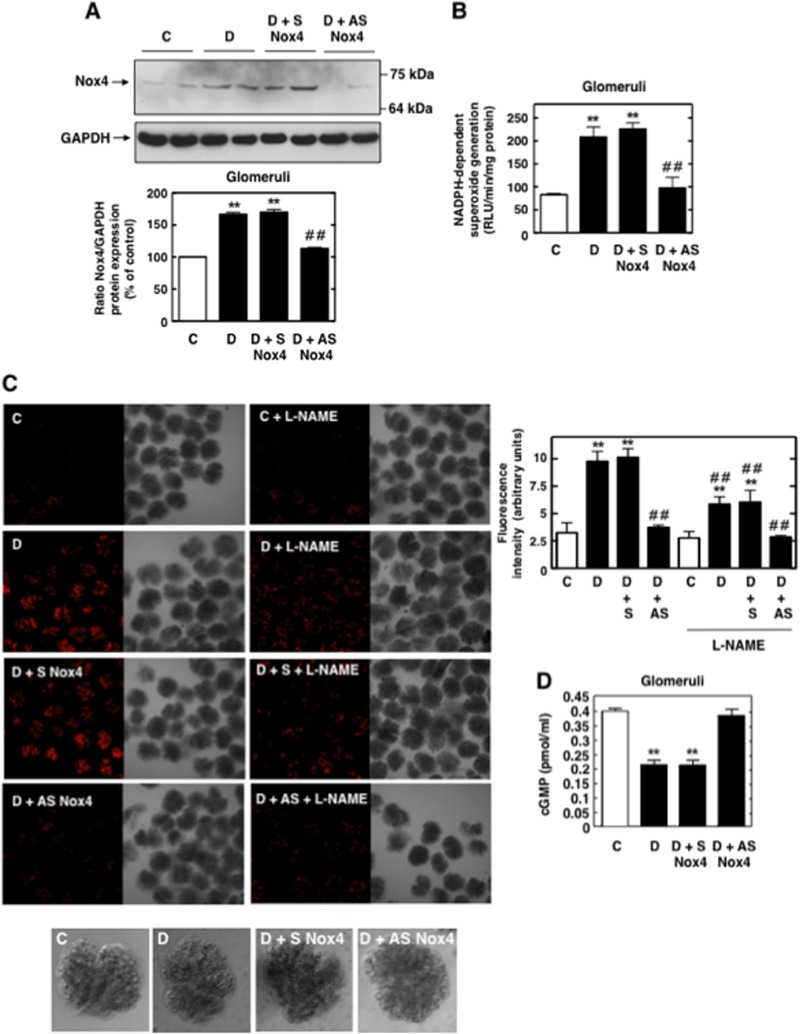

Using Nox4 antisense (AS) phosphorothioated oligonucleotides administered subcutaneously in a streptozotocin (STZ)-induced rat model of type 1 diabetes, we have previously showed that Nox4 is a major source of ROS in diabetes and that Nox4-derived ROS mediate glomerular hypertrophy and matrix protein accumulation (13).

Here, in a new series of in vivo studies with AS Nox4, where type 1 diabetes is induced for 2 weeks, we confirmed that Nox4 protein expression and NADPH-dependent superoxide generation were increased in glomeruli isolated from diabetic rats compared to the levels in glomeruli from control nondiabetic rats (Fig. 7A and B). AS Nox4 but not sense Nox4 (S Nox4) administration reversed diabetes-induced Nox4 protein expression and NADPH oxidase activity in glomeruli from diabetic animals. Studies with isolated glomeruli incubated in vitro with DHE showed that L-NAME reduced the increase in superoxide generation in glomeruli isolated from diabetic rats or diabetic rats treated with S Nox4 compared with the superoxide generation in glomeruli isolated from control animals (Fig. 7C). Note that in the glomeruli prepared from AS Nox4-treated animals, L-NAME did not cause a further decrease in DHE fluorescence (Fig. 7C). The observation that L-NAME only partially inhibited DHE staining in diabetic or S Nox4-treated diabetic groups (Fig. 7C) indicates that both Nox4 and NOS contribute to oxidative stress in diabetic glomeruli. These data strongly support the concept that NOS dysfunction contributes to diabetes-induced oxidative stress in vivo. Importantly, we also provide evidence that inhibition of Nox4 by the administration of AS prevents NOS dysfunction/uncoupling and the decrease in NO-mediated cGMP levels in glomeruli from diabetic animals (Fig. 7D).

Fig 7.

Nox4-derived ROS mediates diabetes-induced decrease in nitric oxide bioavailability in glomeruli. (A) Expression of Nox4 protein was determined by direct immunoblotting of homogenized glomeruli. Representative results of Western blot analysis were obtained from two independent samples from each group. Bottom, histogram represents the ratios of the intensities of the Nox4 bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of the actin GAPDH bands. The data are expressed as percentages of control (untreated or untransfected cells), where the ratio in the control was defined as 100%. Values are the means ± SE from four animals in each group. **, P < 0.01 versus control rats; ##, P < 0.01 versus diabetic rats. (B) NADPH oxidase activities in glomerular homogenates from diabetes (D), diabetes plus sense Nox4 (D + S Nox4), diabetes plus AS Nox4 (D + AS Nox4), and control (C) groups. NADPH-dependent superoxide generation was measured by lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence as described in the legend to Fig. 6B and D. Data represent the means ± SE of the activities from glomeruli of four animals for each group. **, P < 0.01 versus control rats; ##, P < 0.01 versus diabetic rats. (C) ROS production in isolated glomeruli was detected using DHE fluorescence. Isolated glomeruli were preincubated with or without L-NAME (100 μM) and then loaded with 10 μM DHE in the dark for 30 min at 37°C. After a wash with HBSS, the glomeruli were placed in cover glass chambers and fluorescence was monitored by laser confocal microscopy. Representative pictures from four rats per group are shown. Right, relative levels of DHE fluorescence (arbitrary units) were semiquantified. Histogram represents the means ± SE of 10 individual glomeruli in sections from four individual rats in each group. **, P < 0.01 versus control rats; ##, P < 0.01 versus diabetic rats. Bottom, photographs of the isolated glomeruli. (D) cGMP formation was measured in isolated glomeruli. Values are the means ± SE of four different animals. **, P < 0.01 versus control rats.

These findings confirm the relevance of our in vitro findings in cultured glomerular cells to oxidative stress in glomeruli in diabetes and identify an important role for Nox4 in NOS uncoupling in vivo.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) blocks high-glucose-induced Nox4-dependent ROS generation, eNOS dysfunction/decrease in NO bioavailability, and fibronectin expression in MCs.

Because AMPK is a physiological suppressor of oxidative stress (9, 33), we next determined whether AMPK regulates the pathway linking HG, Nox4, eNOS dysfunction, and the subsequent matrix protein accumulation.

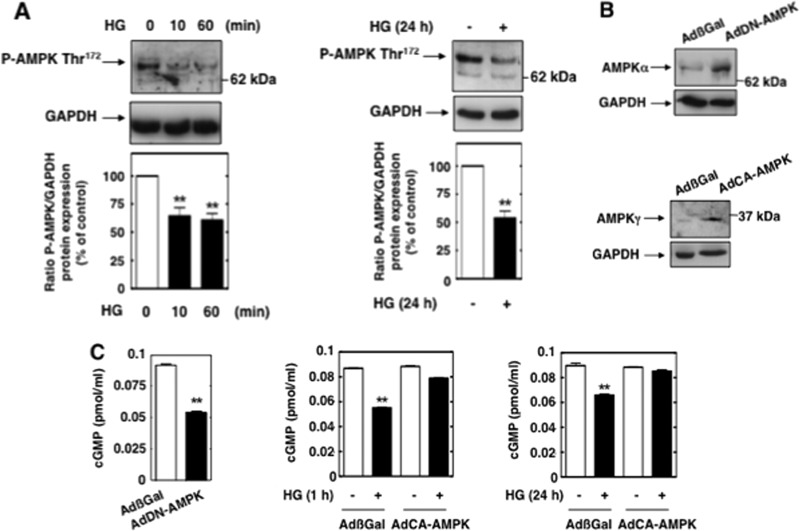

We first examined AMPK phosphorylation on threonine 172, an indicator of AMPK activation, in MCs incubated with HG. As shown by the results in Fig. 8A, a short incubation of MCs with HG caused decreases in AMPK phosphorylation on threonine 172 at 10 min and 60 min. Prolonged exposure of the cells to HG also inhibited AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. 8A).

Fig 8.

AMPK blocks HG-induced eNOS dysfunction in MCs. (A) MCs were treated with HG (25 mM) for the time periods indicated, and AMPK phosphorylation was assessed by direct immunoblotting using anti-phospho-specific antibodies recognizing phosphorylated threonine 172 (P-AMPK Thr172). Bottom, histograms represent the ratios of the intensities of tyrosine-phosphorylated AMPK bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of GAPDH bands. Data are expressed as percentages of the control, where the ratio in the control was defined as 100%. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control. (B) MCs were infected with adenovirus encoding dominant-negative AMPKα2 (AdDN-AMPK), constitutively active AMPKγ (AdCA-AMPK), or β-galactosidase (AdβGal). Overexpression of AMPKα2 and AMPKγ from the adenovirus vectors is shown. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) Left, MCs were infected with AdDN-AMPK or AdβGal, and cGMP synthesis was determined. Middle and right, MCs were infected with AdCA-AMPK or AdβGal and treated with HG (1 h or 24 h), and levels of cGMP synthesis were determined. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus AdβGal-infected cells.

To further investigate the role of AMPK, we introduced an adenovirus encoding a dominant-negative form of the AMPKα2 subunit mutated at lysine 45 (K45R) (AdDN-AMPK) or an AMPKγ subunit with a histidine 150 mutation (H150R) that causes constitutive activation of AMPK (AdCA-AMPK). Adenovirus encoding β-galactosidase (AdβGal) was used as a control. The effectiveness of infection of the adenoviruses is shown in Fig. 8B. The data show that basal NO-mediated cGMP production was decreased in MCs infected with AdDN-AMPK (Fig. 8C, left). Conversely, infection of the cells with AdCA-AMPK completely prevented the HG-induced decrease in NO bioactivity observed at 1 h and 24 h, time points when eNOS is dysfunctional (Fig. 8C, middle and right).

Since Nox4-derived oxidants account for the HG-mediated eNOS dysfunction/decrease in NO levels, we examined the impacts of the different adenoviruses on Nox4 protein expression and NADPH oxidase activity, as well as intracellular superoxide and peroxynitrite generation. Inhibition of AMPK with AdDN-AMPK robustly enhanced the basal expression of Nox4 protein (Fig. 9A), NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 9B), intracellular superoxide generation (Fig. 9C), and 3-nitrotyrosine staining (Fig. 9D). On the other hand, the introduction of constitutively active AMPK using AdCA-AMPK inhibited the HG-induced early increase in Nox4 protein (Fig. 9E), NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 9F), intracellular superoxide (Fig. 9G), and peroxynitrite production (Fig. 9H). We also show that basal fibronectin protein expression was increased in MCs infected with dominant-negative AMPK (Fig. 10A) and that infection of the cells with constitutively active AMPK significantly abrogated HG-induced fibronectin expression (Fig. 10B).

Fig 9.

AMPK blocks HG-induced Nox4-dependent ROS generation in MCs. (A) MCs were infected with AdDN-AMPK or AdβGal, and levels of Nox4 protein expression were assessed by direct immunoblotting. (B) MCs were infected with AdDN-AMPK or AdβGal, and NADPH oxidase activities were determined. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus AdβGal-infected cells. (C and D) MCs were infected with AdDN-AMPK or AdβGal, and levels of DHE fluorescence (C) or 3-nitrotyrosine staining (D) were assessed with confocal laser microscopy. The photomicrographs are representative of three individual experiments. For each panel, fluorescence intensity was semiquantified. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control (AdβGal-infected cells). (E) MCs were infected with AdCA-AMPK or AdβGal and treated with HG (10 min or 1 h), and levels of Nox4 protein expression were assessed by direct immunoblotting. Bottom, histograms represent the ratios of the intensities of Nox4 bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of GAPDH bands. Data are expressed as percentages of control (AdβGal-infected cells), where the ratio in the control was defined as 100%. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control (AdβGal-infected cells); ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in AdβGal-infected cells. (F) MCs were infected with AdCA-AMPK or AdβGal and treated with HG (10 min or 1 h), and NADPH oxidase activities were determined. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control (AdβGal-infected cells); ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in AdβGal-infected cells. (G and H) MCs were infected with AdCA-AMPK or AdβGal and treated with HG (10 min or 1 h), and levels of DHE fluorescence (G) or 3-nitrotyrosine staining (H) were assessed with confocal laser microscopy. Photomicrographs are representative of three individual experiments. For each panel, fluorescence intensity was semiquantified. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control (AdβGal-infected cells); ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in AdβGal-infected cells.

Fig 10.

AMPK blocks HG-induced fibronectin synthesis in MCs, (A) MCs were infected with AdDN-AMPK or AdβGal, and levels of fibronectin protein expression were determined by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top) or by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy (bottom). (B) MCs were infected with AdCA-AMPK or AdβGal and treated with HG (24 h), and levels of fibronectin protein expression were determined by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top) or by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy (bottom). (A and B) Data were quantified and expressed as described in the legend to Fig. 3B and C. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus AdβGal-infected cells; ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in AdβGal-infected cells.

Collectively, our findings indicate that AMPK suppresses oxidative stress and matrix protein accumulation and preserves NO bioactivity through downregulation of Nox4 protein and Nox4-dependent ROS production in MCs. Moreover, inactivation of AMPK by HG results in increases in Nox4 expression and subsequent ROS production that, in turn, result in eNOS dysfunction/decrease in NO bioactivity, as well as fibronectin accumulation in MCs.

Sestrin 2 prevents high-glucose-induced Nox4-dependent ROS generation, eNOS dysfunction/decrease in NO bioavailability, and fibronectin synthesis in MCs.

Sestrin 2 is a stress-inducible protein known to activate AMPK (28, 29, 31). Thus, we reasoned that sestrin 2 is a potential candidate as an upstream regulator of the AMPK/Nox4/uncoupled eNOS/matrix protein accumulation in MCs exposed to HG.

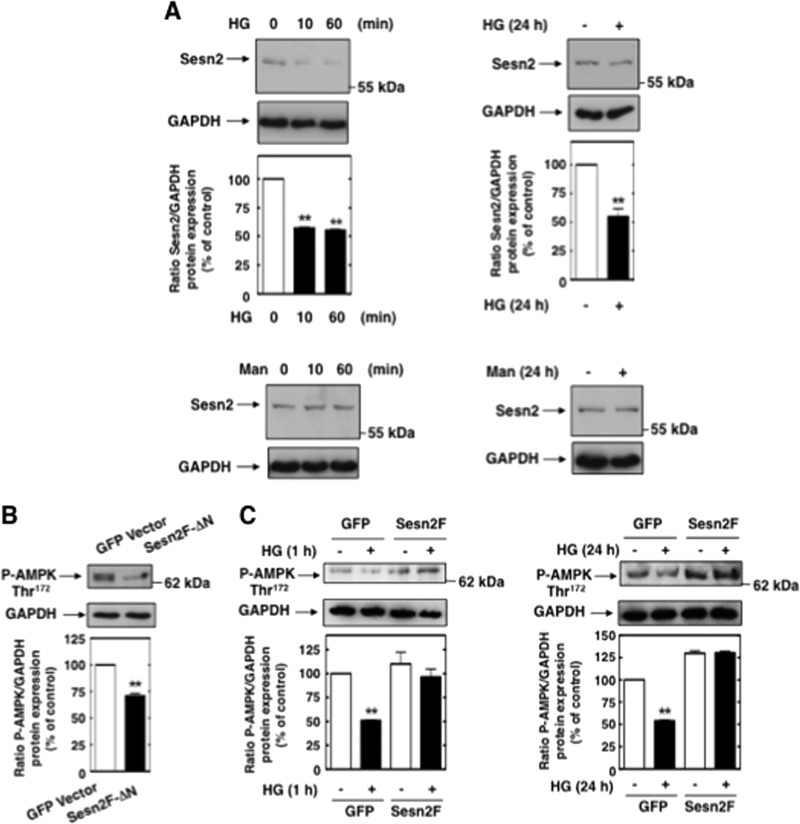

Exposure of MCs to HG downregulates sestrin 2 protein at 10 min and 60 min (Fig. 11A). A similar decrease in sestrin 2 protein was seen after chronic treatment of the cells with HG for 24 h (Fig. 11A). These effects were not observed in cells cultured with the osmotic control. Note the striking parallel between the time courses of the HG-induced decrease in AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. 8A) and HG-induced inhibition of sestrin 2 protein expression (Fig. 11A). Note also the correspondence between the time points at which eNOS was dysfunctional and sestrin 2 was downregulated.

Fig 11.

Sestrin 2 prevents HG-induced AMPK inactivation in MCs. (A) MCs were treated with HG (25 mM) for the time periods indicated, and sestrin 2 protein expression was assessed by direct immunoblotting. Mannitol (Man) (20 mM mannitol + 5 mM d-glucose) was used as osmotic control. Middle, histograms represent the ratios of the intensities of sestrin 2 bands quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of GAPDH bands. The data are expressed as percentages of control, where the ratio in the control was defined as 100%. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control. (B) MCs were transfected with Sesn2F-ΔN or GFP vector, and levels of AMPK phosphorylation were assessed by direct immunoblotting using anti-phospho-specific antibodies recognizing phosphorylated threonine 172 (P-AMPK Thr172). (C) MCs were transfected with Sesn2F or GFP vector and treated with HG (1 h or 24 h), and levels of AMPK phosphorylation were assessed by direct immunoblotting using anti-phospho-specific antibodies recognizing phosphorylated threonine 172 (P-AMPK Thr172). The data were quantified and expressed as described in the legend to Fig. 8A. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus GFP vector-transfected cells.

Sestrin 2 function was modulated using an expression construct with a N-terminally truncated form of sestrin 2 (Sesn2F-ΔN) (unable to bind AMPK) or a construct with a wild-type form of sestrin 2 (Sesn2F). A GFP vector was used as the control. The results in Fig. 11B and C confirm that sestrin 2 activates AMPK, as evidenced by the observations that transfection of truncated sestrin 2 decreased AMPK threonine 172 phosphorylation and that overexpression of wild-type, active sestrin 2 blocked the HG-mediated decreases in AMPK threonine 172 phosphorylation at 1 h and 24 h.

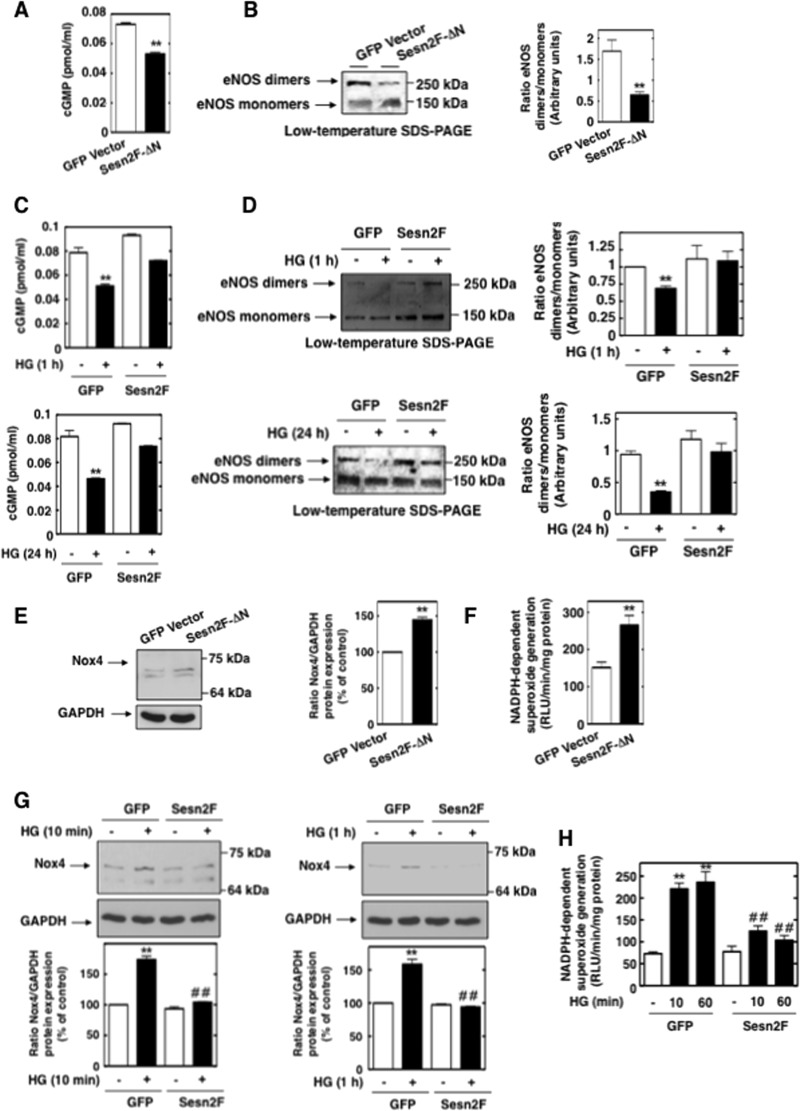

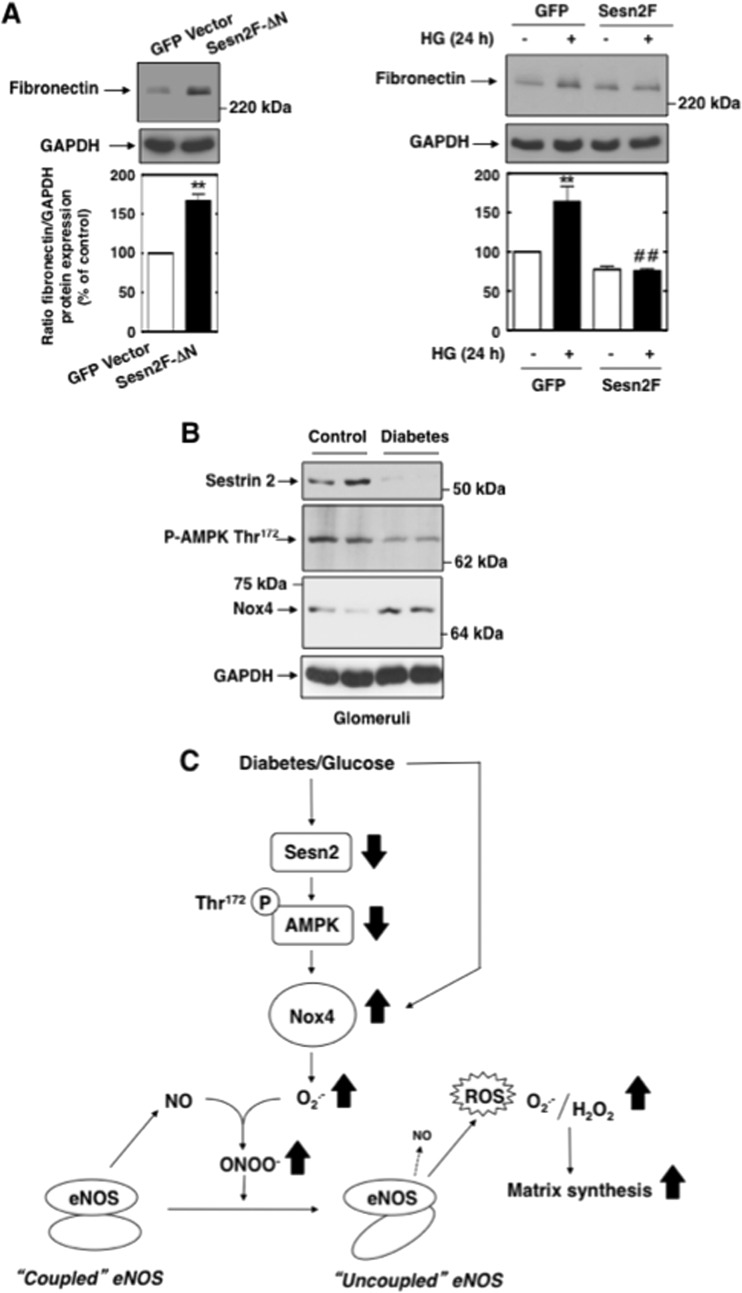

Given that the time periods at which HG decreased sestrin 2 protein expression and AMPK activity corresponded to those when eNOS was uncoupled, we determined whether sestrin 2 regulates eNOS function. Transfection of Sesn2F-ΔN diminished NO bioactivity (Fig. 12A) and disrupted eNOS dimers (Fig. 12B). In contrast, overexpression of active sestrin 2 attenuated the decrease in NO bioactivity (Fig. 12C) and the dissociation of eNOS dimers (Fig. 12D) observed after short-term (1-h) or long-term (24-h) treatment of MCs with HG.

Fig 12.

Sestrin 2 prevents HG-induced Nox4-dependent eNOS dysfunction in MCs. (A and B) MCs were transfected with Sesn2F-ΔN or GFP vector, and levels of cGMP synthesis (A) or eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios (B) were determined. (C and D) MCs were transfected with Sesn2F or GFP vector and treated with HG (1 h or 24 h), and levels of cGMP synthesis (C) or eNOS dimer-to-monomer ratios (D) were determined. (B and D) Data were quantified and expressed as described in the legend to Fig. 2D. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus GFP vector-transfected cells. (E and F) MCs were transfected with Sesn2F-ΔN or GFP vector, and levels of Nox4 protein expression (E) or NADPH oxidase activities were assessed (F). (E) Right, data were quantified and expressed as described in the legend to Fig. 9E. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control (GFP vector-transfected cells). (G and H) MCs were transfected with Sesn2F or GFP vector and treated with HG (10 min or 1 h), and levels of Nox4 protein expression (G) or NADPH oxidase activities (H) were assessed. (G) Bottom, data were quantified and expressed as described in the legend to Fig. 9E. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control (GFP vector-transfected cells); ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in GFP vector-transfected cells.

Using the same expression constructs, we also linked sestrin 2 to Nox4-dependent ROS generation and extracellular matrix synthesis. Inhibition of sestrin 2 function with Sesn2F-ΔN enhanced basal Nox4 protein expression (Fig. 12E), as well as NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 12F). Overexpression of functional sestrin 2 attenuated the early increase in Nox4 protein induced by HG (Fig. 12G), as well as NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 12H). Moreover, Sesn2F-ΔN enhanced basal fibronectin expression (Fig. 13A, left), and Sesn2F blocked the delayed effect of HG on fibronectin (Fig. 13A, right). Using the glomeruli prepared from type 1 diabetic rats, we probed for sestrin 2, AMPK phosphorylation on threonine 172, and Nox4. Interestingly, the increase in Nox4 protein was associated with decreases in sestrin 2 protein expression and AMPK threonine 172 phosphorylation in glomeruli from diabetic animals compared to their levels in glomeruli from control animals (Fig. 13B), indicating that the regulation of the sestrin 2/AMPK/Nox4 axis also takes place in vivo.

Fig 13.

(A) Sestrin 2 prevents HG-induced fibronectin synthesis in MCs. Left, MCs were transfected with Sesn2F-ΔN or GFP vector, and levels of fibronectin protein expression were assessed. Right, MCs were transfected with Sesn2F or GFP vector and treated with HG for the indicated times, and levels of fibronectin protein expression were assessed. Data were quantified and expressed as described in the legend to Fig. 3B. Values are the means ± SE from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus control (GFP vector-transfected cells); ##, P < 0.01 versus HG in GFP vector-transfected cells. (B) Downregulation of sestrin 2 is associated with a decrease in AMPK phosphorylation and an increase in Nox4 expression in glomeruli from diabetic rats. Sestrin 2 and Nox4 protein expression or AMPK phosphorylation on Thr172 were detected by direct immunoblotting in glomerular homogenates. Representative Western blot analysis was obtained from two independent samples from each group (Control and Diabetes). (C) Proposed molecular mechanisms of HG-induced fibronectin synthesis in MCs. See Discussion for details.

These data strongly suggest that sestrin 2-dependent AMPK activation negatively regulates Nox4-mediated eNOS dysfunction and the subsequent matrix protein accumulation induced by HG in MCs. Moreover, HG appears to enhance the Nox4-dependent eNOS dysfunction and MC fibrotic response by promoting the downregulation of sestrin 2 that, in turn, leads to AMPK inactivation.

DISCUSSION

A role for dysfunctional eNOS as a source of ROS in glomeruli from diabetic animals or in MCs exposed to HG has been reported (19–23). However, the mechanisms leading to eNOS uncoupling by HG and in diabetes are not known.

The present studies reveal that dysfunctional eNOS contributes relatively early to ROS production and decreased NO bioactivity in glucose-treated MCs and becomes a prominent source of superoxide that enhances fibronectin accumulation after sustained exposure of the cells to HG. Mechanistically, our data indicate that the early acute peroxynitrite production mediates eNOS dysfunction, as well as the subsequent deficiency in NO production and fibrotic response observed after exposure to HG. Peroxynitrite, the reaction product of NO and superoxide, is known to uncouple oxygen reduction from NO generation in eNOS (15–17, 38, 43). Peroxynitrite acts via oxidation of BH4 or oxidative damage to the zinc-thiolate cluster with a zinc ion tetrahedrally coordinated to pairs of cysteine residues localized at the eNOS dimer interface. These cysteines are implicated in BH4 binding and in the maintenance of the physical integrity of the dimer in its active form (15, 16, 38, 45). The published reports showing that BH4 supplementation restores NO levels and eNOS function in HG-treated MCs or in glomeruli from diabetic rats support the contention that the alteration of BH4 levels contributes to eNOS dysfunction (22, 46). The dissociation of eNOS dimers into monomers by low-temperature SDS-PAGE in MCs incubated with HG indirectly implicates peroxynitrite as the uncoupling factor. Indeed, this assay is based on the property that oxidation of the zinc-thiolate center by anionic oxidants, such as peroxynitrite, leads to a loss of zinc and the formation of disulfide bonds between eNOS monomers that can be broken under reducing conditions (β-mercaptoethanol), leading to dissociation of eNOS dimers (38). Our data demonstrating that the peroxynitrite scavenger uric acid prevents the HG-mediated eNOS dimer disruption and the decrease in NO levels confirm that peroxynitrite plays a key role in the alteration of eNOS dimer stability and eNOS function in MCs exposed to HG.

NADPH oxidases of the Nox family have been proposed to be the source of the kindling radicals that contribute to the formation of peroxynitrite, initiating eNOS dysfunction (16, 17, 45). In the present study, we unveil a functional link between Nox4 and eNOS dysfunction/decrease in NO bioavailability in cultured MCs exposed to HG, as well as in vivo in glomeruli of a type 1 diabetic rat model. Our findings identify Nox4 as a pivotal mediator of HG- or diabetes-induced eNOS dysfunction and strongly suggest that the molecular mechanisms underlying this process may involve the reaction of Nox4-derived superoxide with NO generated constitutively by functional eNOS, resulting in the formation of peroxynitrite that subsequently uncouples eNOS, further promoting superoxide generation. We have previously reported that ROS generated by Nox4 are required for the stimulatory effects of HG and diabetes on extracellular matrix protein accumulation in MCs and in glomeruli (9, 13, 14). Here, we provide new insights concerning the molecular mechanism involved in these events and demonstrate that Nox4/peroxynitrite-dependent eNOS uncoupling with decreased NO contributes to HG-induced fibronectin expression.

While our data are consistent with a recent report demonstrating Nox4-dependent peroxynitrite production in hepatocytes (47), the present observations linking Nox4 to peroxynitrite formation and eNOS uncoupling are intriguing. Nox4 is frequently alleged to predominantly generate hydrogen peroxide rather than superoxide (48–52). This property of the oxidase may have important implications for the interaction with NO signaling, since hydrogen peroxide, unlike superoxide, does not react with NO to form peroxynitrite and may even stimulate eNOS activity (49, 51–54). Hence, it was recently described that Nox4 enhances eNOS activity and NO signaling (52–54). Consistent with these observations, the Nox oxidases that have been linked to eNOS uncoupling in vascular pathology, including diabetes, are the superoxide-generating isoforms Nox1 and Nox2 (also known as gp91phox) (55–58). However, numerous studies in cardiac, vascular, or renal cells and tissue demonstrated Nox4-dependent superoxide production (9, 13, 14, 59–61). Several of these reports recorded superoxide generation using HPLC analysis of DHE-derived oxidation products, as in the present work, or via electron paramagnetic/spin resonance, two gold standards for superoxide measurement (59–61). Therefore, even if Nox4 produces less superoxide than hydrogen peroxide, it is conceivable that the superoxide will react with NO to form peroxynitrite. It was recently proposed that the propensity of Nox4 to produce predominantly hydrogen peroxide rather than superoxide is due to a specific extracellular domain called E-loop that may form a confined environment, restricting the release of superoxide, or constitute a source of protons, favoring rapid dismutation of superoxide into hydrogen peroxide (4, 49, 52). The subcellular localization of Nox4 to intracellular membranes of various compartments or organelles (such as focal adhesions, endoplasmic reticulum, plasma membrane, mitochondria, and nucleus) (4, 14, 48, 60, 61) may render more problematic the detection of the superoxide generated by the oxidase. Regardless of these considerations, it is reasonable to speculate that the readily diffusible and membrane-permeable NO is able to access any of the subcellular compartments containing Nox4 and reach the core of the specific domain of Nox4 where superoxide is generated/sequestered to instantly produce peroxynitrite before the dismutation of superoxide. Importantly, the concept of ROS-induced ROS release between Nox isoforms cannot be excluded as explaining, at least partially, the implication of Nox4 in peroxynitrite formation. In cells like MCs that express multiple Nox homologs (5), the hydrogen peroxide generated by Nox4 may stimulate the activity of another Nox isoform (such as Nox2 or Nox1) that predominantly generates superoxide. There are numerous examples of the regulation of the expression and activity of Nox homologs, including Nox4, by hydrogen peroxide (4, 62, 63).

The stress-inducible proteins of the sestrin family, especially sestrin 2, suppress ROS and protect from oxidative stress (28). However, the mechanisms by which sestrin 2 exerts its antioxidant properties remain unclear. It was initially proposed that sestrin 2 acts by regenerating hyperoxidized peroxiredoxins, the enzymes that catalyze the reduction of hydroperoxides, but this is currently controversial (28, 64). Here, we report a novel molecular mechanism by which sestrin 2 inhibits oxidative stress and demonstrate that sestrin 2 attenuates HG-induced ROS generation and MC injury through blockade of Nox4-dependent eNOS dysfunction/decline in NO levels. Specifically, we show that sestrin 2 counteracts Nox4-mediated ROS production by impeding the early and rapid upregulation of Nox4 protein elicited by HG. Our results also indicate that AMPK functions as a mediator of sestrin 2's inhibitory effects on HG-stimulated and Nox4-dependent eNOS dysfunction and extracellular matrix protein accumulation in MCs. This is in agreement with the data from the literature showing that sestrin 2 interacts with AMPK to potentiate its phosphorylation and activation (28, 29, 31). We found that AMPK activation negatively regulates the Nox4 protein expression and ROS production stimulated by HG. These observations are supported by numerous published studies showing that AMPK constitutes a physiological suppressor of ROS production via inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation and the expression of Nox subunits, including Nox4 (9, 32, 33, 65–67).

Another novel finding of this study is that sestrin 2-dependent AMPK activation attenuates the early and rapid effects of HG on Nox4 and NADPH oxidase activity in MCs. These data are consistent with the possibility that sestrin 2- and AMPK-mediated control of Nox4 expression and subsequent ROS production occurs by translation. Interestingly, sestrin 2 is a potent inhibitor of the mTORC1/p70 S6 kinase/4E-BP1 translational pathway through the activation of AMPK (28–30). In addition, various agonists implicated in renal diseases, such as HG, transforming growth factor β, angiotensin II, or insulin-like growth factor, cause early Nox4 protein accumulation independent of mRNA transcription by promoting the translation of existing mRNA (6, 14, 34, 35, 68, 69). It is equally remarkable that the downregulation of sestrin 2 by HG occurs relatively early, suggesting that translation may also be implicated in these events.

Importantly, the present work also demonstrates that the protective effects of sestrin 2/AMPK are reciprocally blunted by HG. Hence, we found that HG promotes AMPK inactivation via downregulation of sestrin 2, which in turn results in increased Nox4 and Nox4-dependent ROS production, followed by eNOS uncoupling, a decrease in NO bioavailability, and enhancement of the MC fibrotic response.

In summary, our study identifies a central role of Nox4 as a mediator of renal cell injury in diabetic kidney disease. In the diabetic milieu, augmentation of Nox4-derived ROS uncouples eNOS, not only eliminating the protective effect of eNOS-derived NO but also converting the enzyme to a phlogistic mediator that further enhances ROS generation and the MC fibrotic response. To our knowledge, this is the first report to establish sestrin 2 and AMPK as critical links between HG and Nox4-dependent eNOS dysfunction (Fig. 13C). These results connecting sestrin 2, eNOS function, NO bioavailibility, and matrix protein synthesis in MCs suggest a potential new role for sestrin 2 in the protection of renal function. Nox4 inhibitors, sestrin 2, and AMPK activators or recoupling of eNOS may become viable therapeutic interventions to complement traditional therapy and prevent or reverse the pathological changes associated with diabetic kidney disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part through a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation multiproject grant (Y.G) and an advanced research fellowship grant (A.A.E.) and in part through NIH RO1 DK 079996 (Y.G.) and NIH RO1 GM 052419 (L.J.R.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Kanwar YS, Sun L, Xie P, Liu FY, Chen S. 2011. A glimpse of various pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6:395–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abboud HE. 2012. Mesangial cell biology. Exp. Cell Res. 318:979–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh DK, Winocour P, Farrington K. 2011. Oxidative stress in early diabetic nephropathy: fueling the fire. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 7:176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassègue B, San Martín A, Griendling KK. 2012. Biochemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology of NADPH oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 110:1364–1390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nistala R, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. 2008. Redox control of renal function and hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10:2047–2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes JL, Gorin Y. 2011. Myofibroblast differentiation during fibrosis: role of NAD(P)H oxidases. Kidney Int. 79:944–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong X, Schröder K. 2009. NADPH oxidases are responsible for the failure of nitric oxide to inhibit migration of smooth muscle cells exposed to high glucose. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47:1578–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai D, Wang B, Shen L, Pu J, Zhang XK, He B. 2008. RXR agonists inhibit high-glucose-induced oxidative stress by repressing PKC activity in human endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44:1334–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eid AA, Ford BM, Block K, Kasinath BS, Gorin Y, Ghosh-Choudhury G, Barnes JL, Abboud HE. 2010. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) negatively regulates Nox4-dependent activation of p53 and epithelial cell apoptosis in diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 285:37503–37512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sedeek M, Callera G, Montezano A, Gutsol A, Heitz F, Szyndralewiez C, Page P, Kennedy CR, Burns KD, Touyz RM, Hébert RL. 2010. Critical role of Nox4-based NADPH oxidase in glucose-induced oxidative stress in the kidney: implications in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 299:F1348–F1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Wang JJ, Yu Q, Chen K, Mahadev K, Zhang SX. 2010. Inhibition of reactive oxygen species by lovastatin downregulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and ameliorates blood-retinal barrier breakdown in db/db mice: role of NADPH oxidase 4. Diabetes 59:1528–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maalouf RM, Eid AA, Gorin YC, Block K, Escobar GP, Bailey S, Abboud HE. 2012. Nox4-derived reactive oxygen species mediate cardiomyocyte injury in early type 1 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 302:C597–C604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorin Y, Block K, Hernandez J, Bhandari B, Wagner B, Barnes JL, Abboud HE. 2005. Nox4 NAD(P)H oxidase mediates hypertrophy and fibronectin expression in the diabetic kidney. J. Biol. Chem. 280:39616–39626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Block K, Gorin Y, Abboud HE. 2009. Subcellular localization of Nox4 and regulation in diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:14385–14390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alp NJ, Channon KM. 2004. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by tetrahydrobiopterin in vascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24:413–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Förstermann U, Münzel T. 2006. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease: from marvel to menace. Circulation 113:1708–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kietadisorn R, Juni RP, Moens AL. 2012. Tackling endothelial dysfunction by modulating NOS uncoupling: new insights into its pathogenesis and therapeutic possibilities. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 302:E481–E495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komers R, Anderson S. 2003. Paradoxes of nitric oxide in the diabetic kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 284:F1121–F1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satoh M, Fujimoto S, Haruna Y, Arakawa S, Horike H, Komai N, Sasaki T, Tsujioka K, Makino H, Kashihara N. 2005. NAD(P)H oxidase and uncoupled nitric oxide synthase are major sources of glomerular superoxide in rats with experimental diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 288:F1144–F1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoh M, Fujimoto S, Arakawa S, Yada T, Namikoshi T, Haruna Y, Horike H, Sasaki T, Kashihara N. 2008. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker ameliorates uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase in rats with experimental diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 23:3806–3813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komers R, Schutzer WE, Reed JF, Lindsley JN, Oyama TT, Buck DC, Mader SL, Anderson S. 2006. Altered endothelial nitric oxide synthase targeting and conformation and caveolin-1 expression in the diabetic kidney. Diabetes 55:1651–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faria AM, Papadimitriou A, Silva KC, Lopes de Faria JM, Lopes de Faria JB. 2012. Uncoupling endothelial nitric oxide synthase is ameliorated by green tea in experimental diabetes by re-establishing tetrahydrobiopterin levels. Diabetes 61:1838–1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng H, Wang H, Fan X, Paueksakon P, Harris RC. 2012. Improvement of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity retards the progression of diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Kidney Int. 82:1176–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao HJ, Wang S, Cheng H, Zhang MZ, Takahashi T, Fogo AB, Breyer MD, Harris RC. 2006. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency produces accelerated nephropathy in diabetic mice. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17:2664–2669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]