Abstract

Lactobacillus plantarum is frequently found in the fermentation of plant-derived food products, where hydroxycinnamoyl esters are abundant. L. plantarum WCFS1 cultures were unable to hydrolyze hydroxycinnamoyl esters; however, cell extracts from the strain partially hydrolyze methyl ferulate and methyl p-coumarate. In order to discover whether the protein Lp_0796 is the enzyme responsible for this hydrolytic activity, it was recombinantly overproduced and enzymatically characterized. Lp_0796 is an esterase that, among other substrates, is able to efficiently hydrolyze the four model substrates for feruloyl esterases (methyl ferulate, methyl caffeate, methyl p-coumarate, and methyl sinapinate). A screening test for the detection of the gene encoding feruloyl esterase Lp_0796 revealed that it is generally present among L. plantarum strains. The present study constitutes the description of feruloyl esterase activity in L. plantarum and provides new insights into the metabolism of hydroxycinnamic compounds in this bacterial species.

INTRODUCTION

Phenolic acids are abundant, naturally occurring molecules that contribute to the rigidity of plant cell walls. Hydroxycinnamic acids, such as ferulic, sinapic, caffeic, and p-coumaric acids, are found both covalently attached to the cell wall and as soluble forms in the cytoplasm. Esters and amides are the most frequently reported types of conjugates, whereas glycosides occur only rarely (1). Hydroxycinnamates are found in numerous plant foods and in significant quantities in agroindustry-derived by-products. The industrial use of hydroxycinnamates has attracted growing interest since they and their conjugates were shown to be bioactive molecules possessing potential antioxidant activities and health benefits. The removal of these phenolic compounds and the breakdown of the ester linkages between polymers allow their exploitation for numerous industrial and food applications.

Feruloyl esterases, also known as ferulic acid esterases, cinnamic acid esterases, or cinnamoyl esterases, are the enzymes involved in the release of phenolic compounds, such as ferulic, p-coumaric, caffeic, and sinapic acids, from plant cell walls (2). In human and ruminal digestion, feruloyl esterases are important to de-esterify dietary fiber, releasing hydroxycinnamates and derivatives, which have been shown to have positive effects, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities (3). They are also involved in colonic fermentation, where their activities in the microbiota improve the breakdown of ester bonds in hydroxycinnamates (3). The biological properties of hydroxycinnamates depend on their absorption and metabolism. Although there is evidence that food hydroxycinnamates are degraded by the gut microbiota, only limited information on the microorganisms and enzymes involved in this degradation is currently available.

Feruloyl esterases able to hydrolyze hydroxycinnamates have been found in lactic acid bacteria isolated from foods and from the human intestinal microbiota, such as some strains of Lactobacillus gasseri (4), Lactobacillus acidophilus (5), Lactobacillus helveticus (6), and Lactobacillus johnsonii (7–9). This enzymatic activity may provide these Lactobacillus strains with an ecological advantage, as they are often associated with fermentations of plant materials. Lactobacillus plantarum is a lactic acid bacterial species that is most abundant in fermenting plant-derived raw materials and also might colonize the human gastrointestinal tract considerably better than other tested lactobacilli (10). Although several esterase enzymes have been described in L. plantarum (11–20), cinnamoyl esterase activity has not been found yet.

Feruloyl esterases constitute an interesting group of enzymes with a potentially broad range of applications in the food industry, and there is a constant search for such enzymes with more desirable properties for novel food applications; the present study represents the description of a feruloyl esterase enzyme in L. plantarum that is widely distributed among strains of the species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

L. plantarum WCFS1 was kindly provided by M. Kleerebezem (NIZO Food Research, The Netherlands). The strain is a single-colony isolate of L. plantarum NCIMB 8826 that was isolated from human saliva. The strain survives passage through the human stomach (21) and persists in the digestive tracts of mice and humans (22). L. plantarum NC8 and L. plantarum 57/1 strains were kindly provided by L. Axelsson (Norwegian Institute of Food, Fisheries and Aquaculture Research, Norway) and J. L. Ruíz-Barba (Instituto de la Grasa, CSIC, Spain), respectively. The strains L. plantarum CECT 220 (ATCC 8014), CECT 221 (ATCC 14431), CECT 223, CECT 224, CECT 749 (ATCC 10241), CECT 4185, and CECT 4645 were purchased from the Spanish Type Culture Collection (CECT). Strains L. plantarum DSM 1055, DSM 2648, DSM 10492, DSM 13273, and DSM 20246 were purchased from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ). Type strains of L. plantarum subsp. plantarum CECT 748T (ATCC 14917T) and L. plantarum subsp. argentorantesis DSM 16365 were purchased from the CECT and DSMZ, respectively. L. plantarum strains (L. plantarum RM28, RM31, RM34, RM35, RM38, RM39, RM40, RM41, RM71, RM72, and RM73) were isolated from grape must and wine samples (23). Lactobacillus paraplantarum DSM 10641 (ATCC 10776) and DSM 10677 were purchased from the DSMZ and included in the study. L. plantarum strains were routinely grown in MRS medium (Pronadisa, Spain) adjusted to pH 6.5 and incubated at 30°C. For degradation assays, L. plantarum strain WCFS1 was cultivated in a modified basal and defined medium described previously for L. plantarum (24). The basal medium was modified by the replacement of glucose by galactose. This defined medium was used to avoid the presence of phenolic compounds included in nondefined media. The sterilized modified basal medium was supplemented at 1 mM final concentration with filter-sterilized hydroxycinnamoyl esters. The L. plantarum-inoculated media were incubated at 30°C in darkness. The phenolic products were extracted from the supernatants twice with ethyl acetate (one-third of the reaction volume).

Escherichia coli DH10B was used for all DNA manipulations. E. coli BL21(DE3) was used for expression in the pURI3-TEV vector (25). E. coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C and 140 rpm. When required, ampicillin was added to the medium at a concentration of 100 μg/ml.

Hydrolysis of hydroxycinnamoyl esters by L. plantarum cell extracts.

In order to prepare cell extracts, L. plantarum strain WCFS1 was grown in 500 ml of MRS medium at 30°C until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 was reached (105 to 106 cells/ml). The cultures were induced by adding 3 mM methyl ferulate and further incubated for 3 h; uninduced cultures were grown in the absence of the hydroxycinnamoyl ester. After induction, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (7,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C), washed three times with sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM; pH 7), and subsequently resuspended in the same buffer (10 ml) for cell rupture. Bacterial cells were disintegrated twice using a French press at 1,500-lb/in2 pressure. The suspension of disintegrated cells was centrifuged at 17,400 × g for 40 min at 4°C in order to sediment the cell debris. The supernatant containing the soluble proteins was filtered aseptically using sterile filters of 0.22-μm pore size (Sarstedt, Germany).

To determine whether uninduced or induced L. plantarum cells possessed enzymes able to hydrolyze hydroxycinnamoyl esters, cell extracts were incubated in the presence of the four model substrates for feruloyl esterase activity (methyl ferulate, methyl caffeate, methyl p-coumarate, and methyl sinapinate; Apin Chemicals, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom) at 1 mM final concentration. L. plantarum cell extracts (2 mg/ml of total protein) were incubated for 16 h at 30°C in the presence of each hydroxycinammoyl ester. The reaction products were extracted twice with ethyl acetate (Lab-Scan, Ireland) for subsequent analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Production and purification of recombinant L. plantarum esterase.

The gene lp_0796 from L. plantarum WCFS1, coding for a putative esterase/lipase, was PCR amplified with HS Prime Start DNA polymerase (TaKaRa) by using the primers 703 (GGTGAAAACCTGTATTTCCAGGGCatgatgctgaaacaaccggaaccgt) and 704 (ATCGATAAGCTTAGTTAGCTATTAtcatttataaatagtttttaaatat) (the nucleotides pairing with the expression vector sequence are in italics, and the nucleotides pairing with the lp_0796 gene sequence are in lowercase letters). The pURI3-TEV vector encodes expression of a leader sequence containing a six-histidine affinity tag. The corresponding 831-bp purified PCR product was then inserted into the pURI3-TEV vector by using a restriction enzyme- and ligation-free cloning strategy (25). E. coli DH10B cells were transformed, and the recombinant plasmids were isolated. Those containing the correct insert, as identified by restriction enzyme analysis, were further verified by DNA sequencing and used for transformation of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells.

E. coli cells carrying the recombinant plasmid pURI3-TEV-0796 were grown at 37°C in LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and induced by adding 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After induction, the cells were grown at 22°C for 20 h and harvested by centrifugation (7,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C). The cells were resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 300 mM NaCl. Crude extracts were prepared by French press lysis of cell suspensions (three cycles at 1,100 lb/in2). The lysate was centrifuged at 17,400 × g for 40 min at 4°C.

The supernatant obtained was filtered through a 0.22-μm filter (Millipore) and gently mixed for 20 min at room temperature with 1 ml Talon resin (Clontech). The resin was washed with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole. The recombinant His6-tagged protein was eluted with 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, containing 300 mM NaCl and 150 mM imidazole. The eluted His6-tagged Lp_0796 was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 300 mM NaCl. The purity of the enzyme was determined by 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in Tris-glycine buffer.

HPLC analysis of feruloyl esterase activity.

Feruloyl esterase activity was measured against four model substrates, methyl ferulate, methyl caffeate, methyl p-coumarate, and methyl sinapinate (Apin Chemicals, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom). The assays for the methyl esters of hydroxycinnamic acids were carried out in a final volume of 1 ml at 37°C in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 1 mM substrate, and 100 μg of protein. The reaction was terminated with ethyl acetate after 16 h reaction time.

The reaction products were extracted twice with one-third of the reaction volume of ethyl acetate (Lab-Scan, Ireland). The ethyl acetate was directly injected onto the column and analyzed by HPLC-diode array detection (DAD). A Thermo (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) chromatograph equipped with a P4000 SpectraSystem pump, an AS3000 autosampler, and a UV6000LP photodiode array detector were used. A gradient of solvent A (water-acetic acid, 98:2 [vol/vol]) and solvent B (water-acetonitrile-acetic acid, 78:20:2 [vol/vol/vol]) was applied to a reversed-phase Nova-Pack C18 cartridge (25 cm by 4.0-mm inside diameter [i.d.], 4.6-μm particle size) at room temperature as follows: 0 to 55 min, 80% B linear, 1.1 ml/min; 55 to 57 min, 90% B linear, 1.2 ml/min; 57 to 70 min, 90% B isocratic, 1.2 ml/min; 70 to 80 min, 95% B linear, 1.2 ml/min; 80 to 90 min, 100% linear, 1.2 ml/min; 100 to 120 min, washing at 1.0 ml/min and reequilibration of the column under initial gradient conditions. Samples were injected onto the cartridge after being filtered through a 0.45-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) filter. Detection of the substrates and the degradation compounds was performed by scanning from 220 to 380 nm. The identification of degradation compounds was carried out by comparing the retention times and spectral data of each peak with those of standards from commercial suppliers or by LC-DAD/electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS).

Enzyme activity assays.

Esterase activity was determined by a spectrophotometric method using p-nitrophenyl butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich) as the substrate. The rate of hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl butyrate for 10 min at 37°C was measured in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at 348 nm in a spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240; Shimadzu). The reaction was stopped by chilling on ice.

In order to carry out the reaction (1 ml), a stock solution of 25 mM p-nitrophenyl butyrate was prepared in acetonitrile-isopropanol (1:4 [vol/vol]) (26) and mixed with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to obtain a 1 mM substrate final concentration. Control reaction mixtures containing no enzyme were utilized to account for any spontaneous hydrolysis of the substrates tested. Enzyme assays were performed in triplicate.

Substrate specificity.

To investigate the substrate specificity of Lp_0796, activity was determined using different p-nitrophenyl esters of various chain lengths (Sigma-Aldrich)—p-nitrophenyl acetate (C2), p-nitrophenyl butyrate (C4), p-nitrophenyl caprylate (C8), p-nitrophenyl laurate (C12), p-nitrophenyl myristate (C14), and p-nitrophenyl palmitate (C16)—as substrates. A stock solution of each p-nitrophenyl ester was prepared in acetonitrile-isopropanol (1/4 [vol/vol]). The substrates were emulsified to a final concentration of 0.5 mM in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 1.1 mg/ml gum arabic and 4.4 mg/ml Triton X-100 (18). Reaction mixtures consisted of 990 μl of emulsified substrate and 10 μl of enzyme solution (1 μg protein). Reactions were carried out at 37°C in a spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240; Shimadzu) as described above.

The enzymatic substrate profile of purified protein was determined by using an ester library described previously (27). p-Nitrophenol was used as a pH indicator to monitor ester hydrolysis colorimetrically. The screening was performed in a 96-well flat-bottom plate (Sarstedt), where each well contained a different substrate (1 mM) in acetonitrile (1%). A buffer/indicator solution containing 0.44 mM p-nitrophenol in 1 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, was used as a pH indicator. Ten micrograms of esterase solution (20 μl in 1 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2) was added to each well, and the reactions were followed by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 410 nm for 2 h at 37°C in a Synergy HT BioTek microplate spectrophotometer. Blank reactions without enzyme were carried out for each substrate, data were collected in triplicate, and the average activities were quantified. The results are shown as means ± standard deviations.

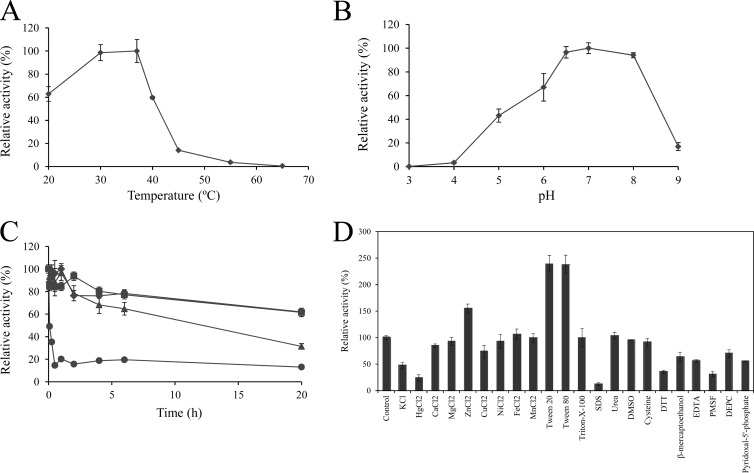

Effects of temperature, pH, and additives on esterase activity.

In order to investigate the temperature effect, reactions were performed in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 20, 30, 37, 40, 45, 55, and 65°C. The effect of pH was studied by assaying esterase activity in a range of pH values from 3.0 to 9.0. The buffers (100 mM) used were acetic acid-sodium acetate buffer (pH 3 to 5), sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6 to 7), Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8), and glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 9). For temperature stability measurements, the esterase was incubated in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 20, 30, 37, 45, 55, and 65°C for 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 20 h. After incubation, the residual activity was measured as described above. To test the effects of metals and ions on the activity of the esterase, the enzyme was incubated in the presence of different additives at a final concentration of 1 mM for 5 min at room temperature. Then, the substrate was added, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C. The additives analyzed were MgCl2, KCl, MnCl2, FeCl2, CuCl2, NiCl2, CaCl2, HgCl2, ZnCl2, diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC), cysteine, SDS, dithiothreitol (DTT), Triton X-100, urea, Tween 80, Tween 20, EDTA, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), pyridoxal-5-phosphate, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and β-mercaptoethanol. In all cases, the analysis was performed in triplicate.

Bacterial-DNA extraction and PCR detection of lp_0796.

Bacterial chromosomal DNA was isolated from overnight cultures. Briefly, L. plantarum strains grown in MRS broth were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in TE solution (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) containing 10 mg/ml of lysozyme (Sigma, Germany). Cells were lysed by adding SDS (1%) and proteinase K (0.3 mg/ml). The crude DNA preparation was purified by performing two phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extractions and one chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extraction. Chromosomal DNA was precipitated by adding 2 volumes of cold ethanol. Finally, the DNA precipitate was resuspended in TE solution.

The lp_0796 gene encoding Lp_0796 esterase was amplified by PCR using 10 ng of chromosomal DNA. PCRs were performed in 0.2-ml centrifuge tubes in a total volume of 25 μl containing 1 μl of template DNA (approximately 10 ng), 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 1 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase, and 1 μM each primer. The reactions were performed using oligonucleotides 703 and 704 to amplify the lp_0796 gene. The reactions were performed in a Personnel Eppendorf thermocycler using the following cycling parameters: an initial 10 min at 98°C for enzyme activation, denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 50°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. The expected size of the amplicon was 0.8 kb. PCR fragments were resolved on 0.7% agarose gels.

RESULTS

Hydrolysis of hydroxycinnamoyl esters by L. plantarum WCFS1.

In order to find out whether L. plantarum WCFS1 has the ability to hydrolyze hydroxycinnamoyl esters, two different experimental approaches were followed. First, L. plantarum cultures were grown for 7 days in the presence of the four model substrates for feruloyl esterases (methyl ferulate, methyl caffeate, methyl p-coumarate, and methyl sinapinate) at 1 mM final concentration. In the cases where L. plantarum cells were able to metabolize the hydroxycinnamoyl esters assayed, the end products could be detected in the culture media. In addition, cell extracts from methyl ferulate-induced and noninduced cultures were incubated at 30°C for 16 h in the presence of 1 mM each of the four model substrates.

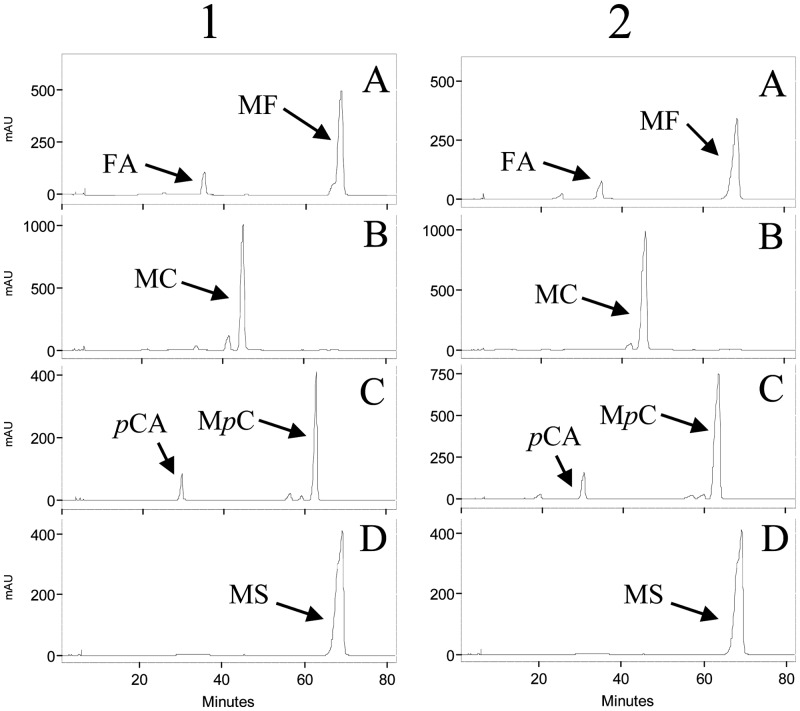

The results indicated that L. plantarum WCFS1 cell cultures were unable to hydrolyze any of the four model substrates tested (data not shown). However, interestingly, methyl ferulate and methyl p-coumarate were partially hydrolyzed by L. plantarum WCFS1 cell extracts (Fig. 1). No significant differences in hydrolysis were observed between methyl ferulate-induced extracts and uninduced extracts, indicating that the enzymatic activity involved is not inducible by the presence of methyl ferulate in the culture medium under our experimental conditions.

Fig 1.

HPLC analysis of the degradation of hydroxycinnamoyl esters by L. plantarum WCFS1 cell extracts. Extracts from cultures, noninduced (column 1) or induced by 3 mM methyl ferulate (column 2), were incubated in the presence of 1 mM methyl ferulate (A), methyl caffeate (B), methyl p-coumarate (C), and methyl sinapinate (D) for 16 h. The methyl ferulate (MF), methyl caffeate (MC), methyl p-coumarate (MpC), methyl sinapinate (MS), ferulic acid (FA), and p-coumaric acid (pCA) detected are indicated. The chromatograms were recorded at 280 nm. AU, arbitrary units.

Identification of Lp_0796 as a feruloyl esterase.

L. plantarum WCFS1 cell extracts partially hydrolyzed methyl ferulate and methyl-p-coumarate; therefore, an enzyme possessing feruloyl esterase activity should be present. In this regard, numerous open reading frames (ORFs) encoding putative esterases can be identified from the genomic information of L. plantarum WCFS1, and one such ORF is lp_0796. To check the working hypothesis that Lp_0796 may be a functional feruloyl esterase, therefore, we decided to clone the corresponding ORF.

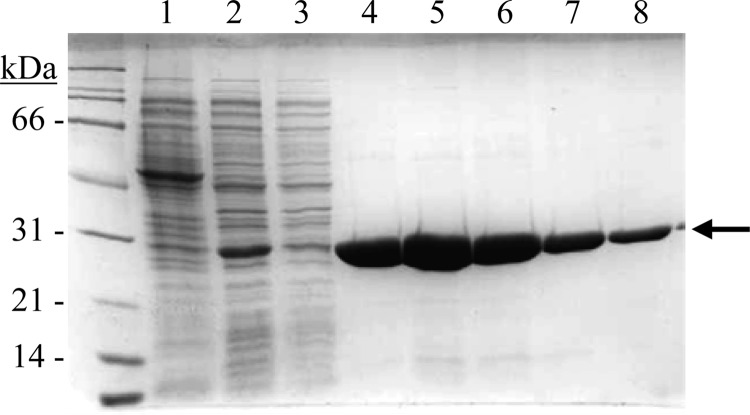

The gene lp_0796 from L. plantarum WCFS1 has been expressed in E. coli under the control of an inducible promoter. Cell extracts were used to detect the presence of overproduced proteins by SDS-PAGE analysis. Whereas control cells containing the pURI3-TEV vector plasmid did not show protein overexpression, an overexpressed protein with an apparent molecular mass around 28 kDa was apparent with cells harboring pURI3-TEV-0796 (Fig. 2). Since the cloning strategy would yield a His-tagged protein variant, L. plantarum Lp_0796 could be purified on an immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) resin. As expected, a protein with the correct molecular mass eluted from the Talon resin by washing with a buffer containing 150 mM imidazole (Fig. 2). The eluted protein was then dialyzed against sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) to remove the imidazole, which may interfere with the feruloyl esterase enzymatic activity assays.

Fig 2.

Purification of L. plantarum Lp_0796 protein. Shown is SDS-PAGE analysis of the expression and purification of His6-Lp_0796 and analysis of soluble cell extracts of IPTG-induced E. coli BL21(DE3)(pURI3-TEV) (lane 1) or E. coli BL21(DE3)(pURI3-TEV-0796) (lane 2), flowthrough from the affinity resin (lane 3), or fractions eluted after His affinity resin (lanes 4 to 8). The arrow indicates the overproduced and purified protein. The 12.5% gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Molecular mass markers are on the left (SDS-PAGE standards; Bio-Rad).

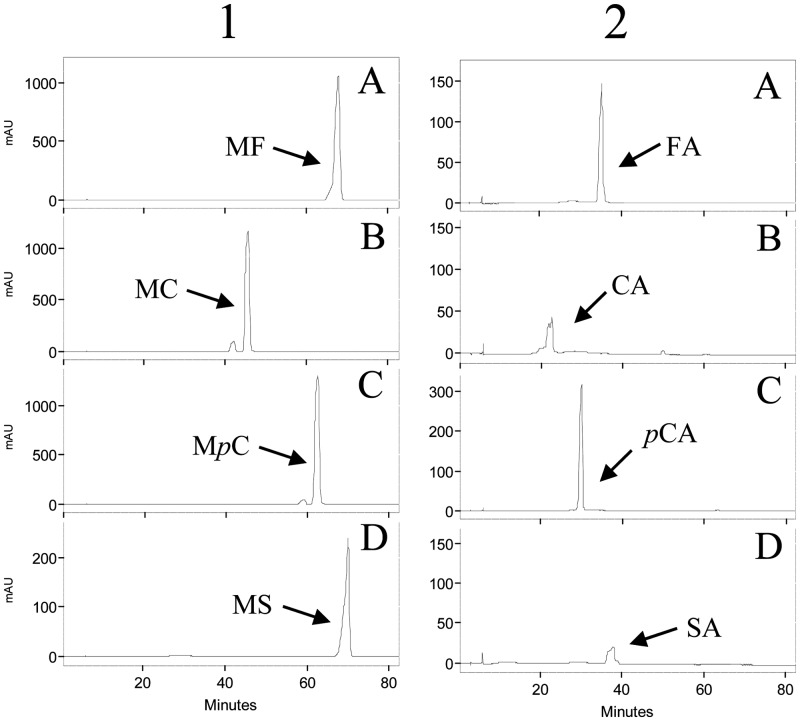

Assay of the feruloyl esterase activity of pure L. plantarum Lp_0796 was performed by using the four hydroxycinnamoyl esters (methyl ferulate, methyl caffeate, methyl p-coumarate, and methyl sinapinate) as substrates at 1 mM final concentration. Figure 3 shows that the four hydroxycinnamoyl esters were fully hydrolyzed by Lp_0796 under our experimental conditions, revealing Lp_0796 as a feruloyl esterase.

Fig 3.

Enzymatic activity of L. plantarum Lp_0796 protein. The hydroxycinnamoyl esterase activity of purified Lp_0796 protein (column 2) was compared with control reactions in which the enzyme was omitted (column 1). Shown are HPLC chromatograms of Lp_0796 (100 μg) incubated in 1 mM methyl ferulate (A), methyl caffeate (B), methyl p-coumarate (C), and methyl sinapinate (MS) for 10 h at 30°C. The methyl ferulate (MF), methyl caffeate (MC), methyl p-coumarate (MpC), methyl sinapinate (MS), ferulic acid (FA), caffeic acid (CA), p-coumaric acid (pCA), and sinapic acid (SA) detected are indicated. The chromatograms were recorded at 280 nm.

Biochemical properties of Lp_0796.

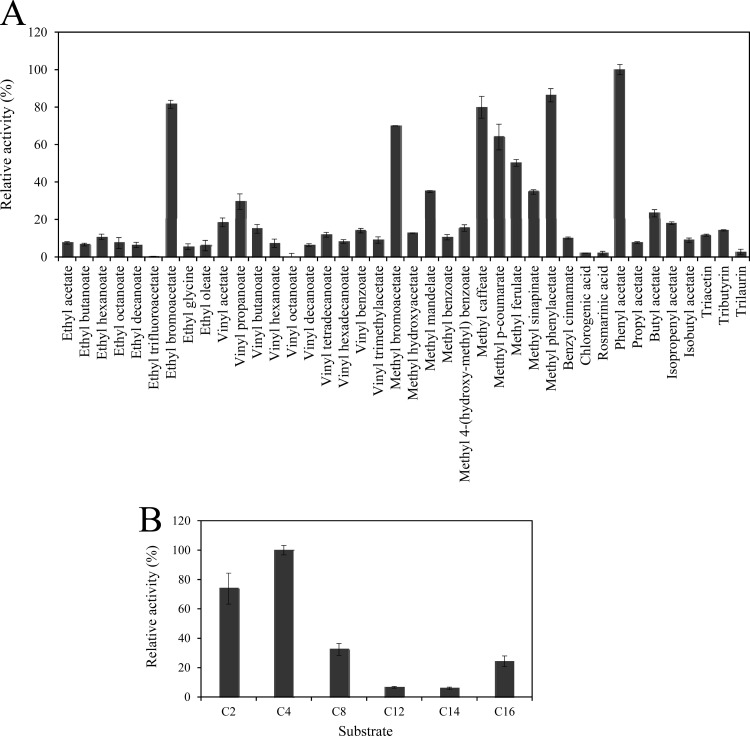

An ester library was used to test the substrate range of Lp_0796. This ester library consisted of esters that were chosen to identify acyl chain length preferences of the esterase and also the ability of Lp_0796 to hydrolyze charged substrates (27). In addition, the activity of Lp_0796 against p-nitrophenyl esters of various chain lengths, from C2 (p-nitrophenyl acetate) to C16 (p-nitrophenyl palmitate), was assayed. The highest hydrolytic activity was observed on phenyl acetate, followed by methyl phenyl acetate and ethyl and methyl bromoacetate (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the ester library confirmed that the four model substrates for feruloyl esterases were efficiently hydrolyzed by Lp_0796 (methyl caffeate, methyl p-coumarate, methyl ferulate, and methyl sinapinate). Other ester substrates were also hydrolyzed, although less efficiently (methyl mandelate, vinyl propanoate, vinyl acetate, vinyl benzoate, vinyl butanoate, methyl benzoate, butyl acetate, and isopropenyl acetate, among others). Regarding the p-nitrophenyl esters assayed, Lp_0796 showed maximum activity against the short-acyl-chain esters, p-nitrophenyl acetate and p-nitrophenyl butyrate (Fig. 4B), although activity against p-nitrophenyl caprilate (C8) and p-nitrophenyl palmitate (C16) was also observed. Therefore, according to the substrates hydrolyzed, it can be concluded that Lp_0796 is a feruloyl esterase with a relatively wide specificity spectrum not described in other esterases from lactic acid bacteria.

Fig 4.

Substrate profile of Lp_0796 toward a general ester library (A) or against chromogenic substrates (p-nitrophenyl esters) with different acyl chain lengths (C2, acetate; C4, butyrate; C8, caprylate; C12, laurate; C14, myristate; C16, palmitate) (B). Shown are the relative specificities obtained toward different substrates. The error bars represent the standard deviations estimated from three independent assays. The observed maximum activity was defined as 100%.

Since feruloyl esterases are enzymes with a broad range of applications and Lp_0796 is a feruloyl esterase described in L. plantarum, its biochemical properties were characterized. Figure 5 shows the optimum pH and temperature and the thermal stability of Lp_0796 determined using p-nitrophenyl butyrate as the substrate. Lp_0796 displays optimal activity at 30 to 37°C, showing marginal activity at 45°C (14% of the maximal activity) (Fig. 5A). In fact, Lp_0796 can be classified as a heat-labile enzyme, since its activity decreased drastically after incubation for a few minutes at 45°C or after 20 h incubation at 22°C, where the esterase showed only 60% of its maximal activity.

Fig 5.

Some biochemical properties of Lp_0796 protein. (A) Relative activity of Lp_0796 versus temperature. (B) Relative activity versus pH. (C) Thermal stability of Lp_0796 after preincubation at 22°C (diamonds), 30°C (squares), 37°C (triangles), and 45°C (circles) in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5). At the indicated times, aliquots were withdrawn and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The experiments were done in triplicate. The mean values and standard errors are shown. The observed maximum activity was defined as 100%. (D) Relative activities of Lp_0796 after incubation with 1 mM concentrations of different additives. The activity of the enzyme incubated in the absence of additives was defined as 100%.

Figure 5D shows the effects of various additives (1 mM final concentration) on the enzymatic activity of Lp_0796. It can be observed that the activity of Lp_0796 was greatly increased by the addition of Tween 20 and Tween 80 (250%) or ZnCl2 (155%); was not significantly affected by FeCl2, NiCl2, MnCl2, cysteine, CaCl2, MgCl2, DMSO, urea, and Triton X-100 (relative activity, 85 to 105%); was only partially inhibited by CuCl2, DEPC, KCl, EDTA, β-mercaptoethanol, and pyridoxal-5-phosphate (relative activity, 55 to 73%); and was greatly inhibited by SDS, HgCl2, DTT, and PMSF (relative activity, 12 to 35%). The effect of Tween 20 on Lp_0796 seems to be concentration dependent, since at a concentration of 1 mM it is an activating additive (250%), whereas at a 5 to 10% concentration, the esterase was inactivated to a significant extent.

Presence of Lp_0796 among L. plantarum strains.

In order to know the extent of the presence of the Lp_0796 feruloyl esterase among L. plantarum strains, the presence of the lp_0796 gene was studied in L. plantarum strains isolated from different origins. To determine the presence of the lp_0796 gene, chromosomal DNA was extracted and PCR amplified. A 0.8-kb gene fragment was PCR amplified using a pair of oligonucleotides designed on the basis of the L. plantarum WCFS1 lp_0796 gene sequence. All the L. plantarum strains analyzed gave the corresponding amplicon, which indicates that Lp_0796 is generally present among L. plantarum strains (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Hydroxycinnamates, such as caffeic, ferulic, and p-coumaric acids, are commonly found as ester conjugates in food plants. Ferulic and p-coumaric acids occur ester-linked to pectin side chains in spinach (28) and to the arabinoxylan of cereal brans (29). L. plantarum is the lactic acid bacterial species most frequently found in the fermentation of plant material, where hydroxycinnamoyl esters are abundant. However, at present, most of the L. plantarum metabolism on phenolic compounds remains largely unknown. Among the L. plantarum esterases already described, only the gallic/protocatechuic acid esterase (also known as tannase) hydrolyzed phenolic compounds (18). This esterase hydrolyzes ester bonds from two hydroxybenzoic acids, gallic and protocatechuic acids. So far, no esterase acting on hydroxycinnamoyl esters from ferulic, caffeic, coumaric, or sinapic acid has been described in L. plantarum strains.

L. plantarum WCFS1 cultures were unable to hydrolyze any of the four model ester substrates for feruloyl esterases, possibly due to the lack of an efficient system of transport to the cell, since cell extracts from the strain partially hydrolyze methyl ferulate and methyl p-coumarate. However, the possibility that other natural or synthetic substrates could pass into the cell and be hydrolyzed by L. plantarum cells cannot be excluded. In order to find the esterase involved in the hydrolytic activity observed in cell extracts, the published sequence of L. plantarum WCFS1 was analyzed, and numerous ORFs encoding putative esterases were found. As a considerable degree of structural diversity among feruloyl esterases has been described (30), it is not possible to predict the biochemical functions of the esterases encoded by these L. plantarum ORFs. The first L. plantarum WCFS1 ORF annotated as a putative esterase (carboxylesterase) gene is lp_0796. While this work was in progress, Lp_0796 (Est0796) was described (20). It was demonstrated that Lp_0796 is an esterase that showed maximum activity toward short acyl chain lengths (C2 to C4). However, the activity of Lp_0796 against hydroxycinnamoyl esters was not analyzed. In the present study, the activity of Lp_0796 against the four model hydroxycinnamoyl esters for feruloyl esterases has been assayed. We demonstrate that these compounds were fully hydrolyzed by Lp_0796 under our experimental conditions, revealing that Lp_0796 shows feruloyl esterase activity. Feruloyl esterases exhibit distinct specificity spectra concerning the release of cinnamic acids, and they are in fact organized into functional classes, which take into account substrate specificity against synthetic methyl esters of hydroxycinnamic acids. According to the present results, Lp_0796 can be considered a type C feruloyl esterase, since it hydrolyzes the four methyl esters of hydroxycinnamic acids generally used as model substrates (31).

It is interesting that the hydrolytic activity observed in L. plantarum cell extracts does not perfectly correlate with the activity observed with the pure Lp_0796 protein, since methyl caffeate and methyl sinapinate were not hydrolyzed by the cell extracts. As only a minor hydrolysis of methyl ferulate and methyl p-coumarate was observed in the cell extracts, it is possible that Lp_0796 could have higher activity on these substrates, and therefore, the activity on methyl caffeate and methyl sinapinate was not detected. However, it is obvious that the presence in L. plantarum WCFS1 of enzymes other than Lp_0796 possessing feruloyl/p-coumaroyl esterase activity cannot be discounted.

The present study constitutes a description of an enzyme possessing hydroxycinnamoyl esterase activity from L. plantarum. However, among lactic acid bacteria, activity against feruloylated esters has been previously described in L. helveticus and L. acidophilus cultures (6) and in purified proteins from L. acidophilus (5) and L. johnsonii (7). Activity against caffeoyl, p-coumaroyl, and sinapyl esters was not tested in these bacteria and proteins.

In addition to the four model substrates for feruloyl esterase, an ester library (27) was used to analyze the substrate range of Lp_0796. Based on the activity profile observed, it can be concluded that Lp_0796 shows a wide substrate range that has not been described in other esterases from lactic acid bacteria. Although chlorogenic acid, a caffeoyl conjugate widely distributed in fruits and vegetables, was not hydrolyzed by Lp_0796, hydrolysis of chlorogenic acid was observed in L. helveticus (6), L. acidophilus (6), and L. gasseri (4); moreover, feruloyl esterases from L. johnsonii also exhibited activity against chlorogenic and rosmarinic acids (7).

It has been reported that L. johnsonii NCC 533 cells hydrolyzed rosmarinic acid, while no cinnamoyl esterase-like activity was observed in either the culture or the reaction media. Moreover, cell extracts from L. johnsonii showed a strong increase of the reaction rate compared to nonlysed cells, suggesting that the enzyme involved in the hydrolysis is presumably intracellular (8). Taking into account that the deduced amino acid sequence of Lp_0796 lacked an N-terminal secretion signal sequence, possibly it is also located intracellularly. Several esterases and lipases from L. plantarum (14, 15) and other lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus casei (32) and Streptococcus thermophilus (33), were also reported to be located intracellularly. These observations suggest that cell lysis may be important for the release of these enzymes during fermentation or during gastrointestinal tract passage.

Most of the metabolism of phenolic compounds in lactic acid bacteria remains unknown; however, the description of new enzymatic activities helps to uncover it. In relation to hydroxycinnamic compounds, a decarboxylase of hydroxycinnamates has been previously described in L. plantarum (34). The subsequent actions of the feruloyl esterase described in the present study (Lp_0796), and that of a vinyl reductase that remains unknown, could allow L. plantarum to metabolize compounds abundant in fermented plant-derived food products (hydroxycinnamoyl esters). However, since the components of plant cells are constituted of complex carbohydrates, the ability of Lp_0796 to degrade this biological material needs further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants AGL2011-22745, BFU2010-17929/BMC, Consolider INGENIO 2010 CSD2007-00063 FUN-C-FOOD (MINECO), S2009/AGR-1469 (ALIBIRD) (Comunidad de Madrid), and RM2012-00004 (Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agraria y Alimentaría). M. Esteban-Torres is the recipient of a JAE predoctoral fellowship from the CSIC.

We are grateful to M. V. Santamaría and J. M. Barcenilla for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Faulds CB, Williamson G. 1999. The role of hydroxycinnamates in the plant cell wall. J. Sci. Food Agric. 79:393–395 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benoit I, Danchin EGJ, Bleichrodt RJ, de Vries RP. 2008. Biotechnological applications and potential of fungal feruloyl esterases based on prevalence, classification and biochemical diversity. Biotechnol. Lett. 30:387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faulds CB. 2010. What can feruloyl esterases do for us? Phytochem. Rev. 9:121–132 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couteau D, McCartney AL, Gibson GR, Williamson G, Faulds CB. 2001. Isolation and characterization of human colonic bacteria able to hydrolyse chlorogenic acid. J. Appl. Microbiol. 90:873–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Geng X, Egashira Y, Sanada H. 2004. Purification and characterization of a feruloyl esterase from the intestinal bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2367–2372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guglielmetti S, De Noni I, Caracciolo F, Molinari F, Parini C, Mora D. 2008. Bacterial cinnamoyl esterase activity screening for the production of a novel functional food product. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1284–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai KL, Lorca GL, González CF. 2009. Biochemical properties of two cinnamoyl esterases purified from a Lactobacillus johnsonii strain isolated from stool samples of diabetes-resistant rats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5018–5024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bel-Rhlid R, Crespy V, Pagé-Zoerkler N, Nagy K, Raab T, Hansen CE. 2009. Hydrolysis of rosmarinic acid from rosemary extract with esterases and Lactobacillus johnsonii in vitro and in a gastrointestinal model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57:7700–7705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bel-Rhlid R, Pagé-Zoerkler N, Fumeaux R, Ho-Dac T, Chuat J-Y, Sauvageat JL, Raab T. 2012. Hydrolysis of chicoric and caftaric acids with esterase and Lactobacillus johnsonii in vitro and in a gastrointestinal model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60:9236–9241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson ML, Molin G, Jeppsson B, Nobaek S, Ahrne S, Bengmark S. 1993. Administration of different Lactobacillus strains in fermented oatmeal soup: in vivo colonization of human intestinal mucosa and effect on the indigenous flora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:15–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oterholm A, Ordal ZJ, Witter LD. 1968. Glycerol ester hydrolase activity of lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. 16:524–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oterholm A, Witter LD, Ordal ZJ. 1972. Purification and properties of an acetyl ester hydrolase (acetylesterase) from Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Dairy Sci. 55:8–13 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen HJ, Ostdal H, Blom H. 1995. Partial purification and characterisation of a lipase from Lactobacillus plantarum MF32. Food Chem. 53:369–373 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gobbetti M, Fox PF, Macchi E, Stepaniak L, Damiani P. 1996. Purification and characterization of a lipase from Lactobacillus plantarum 2739. J. Food Biochem. 20:227–246 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gobbetti M, Fox PF, Stepaniak L. 1997. Isolation and characterization of a tributyrin esterase from Lactobacillus plantarum 2739. J. Dairy Sci. 80:3099–3106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes MF, Cunha AE, Clemente JJ, Carrondo MJ, Crespo MT. 1999. Influence of environmental factors on lipase production by Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51:249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva Lopes MF, Leitao AL, Marques JJ, Carrondo MJ, Crespo MT. 1999. Processing of extracellular lípase of Lactobacillus plantarum: involvement of a metalloprotease. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:483–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curiel JA, Rodríguez H, Acebrón I, Mancheño JM, de las Rivas B, Muñoz R. 2009. Production and physicochemical properties of recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum tannase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57:6224–6230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brod FCA, Vernal J, Bertoldo JB, Terenzi H, Arisi ACM. 2010. Cloning, expression, purification, and characterization of a novel esterase from Lactobacillus plantarum. Mol. Biotechnol. 44:242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navarro-González I, Sánchez-Ferrer A, García-Carmona F. 2013. Overexpression, purification, and biochemical characterization of the esterase Est0796 from Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Mol. Biotechnol. 54:651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vesa T, Pochart P, Marteau P. 2000. Pharmacokinetic of Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 8826, Lactobacillus fermentum KLD, and Lactococcus lactis MG 1363 in the human gastrointestinal tract. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 14:823–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pavan S, Desreumaux P, Mercenier A. 2003. Use of mouse models to evaluate the persistence, safety, and immune modulation capacities of lactic acid bacteria. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:696–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de las Rivas B, Rodríguez H, Curiel JA, Landete JM, Muñoz R. 2009. Molecular screening of wine lactic acid bacteria degrading hydroxycinnamic acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57:490–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozès N, Peres C. 1998. Effects of phenolic compounds on the growth and the fatty acid composition of Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 49:108–111 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curiel JA, de las Rivas B, Mancheño JM, Muñoz R. 2011. The pURI family of expression vectors: a versatile set of ligation independent cloning plasmids for producing recombinant His-fusion proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 76:44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glogauer A, Martini VP, Faoro H, Couto GH, Müller-Santos M, Monteiro RA, Mitchel DA, de Souza EM, Pedrosa OF, Krieger N. 2011. Identification and characterization of a new true lispase isolated through metagenomic approach. Microb. Cell Fact. 10:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu AMF, Somers NA, Kazlauskas RJ, Brush TS, Zocher TS, Enzelberger MM, Bornscheuer UT, Horsman GP, Mezzetti A, Schmidt-Dannert C, Schmid RD. 2001. Mapping the substrate selectivity of new hydrolases using colorimetric screening: lipases from Bacillus thermocatenolatuts and Ophiostoma piliferum, esterases from Pseudomonas fluorescens and Streptomyces diastatochromogenes. Tetrahedrom. Asym. 12:545–556 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fry SC. 1982. Phenolic components of the primary cell wall. Feruloylated disaccharides of D-galactose and L-arabinose from spinach polysaccharide. Biochem. J. 203:493–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith MM, Hartley RD. 1983. Occurrence and nature of ferulic acid substitution of cell wall polysaccharides in graminaceous plants. Carbohydr. Res. 118:65–80 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crepin VF, Faulds CB, Connerton IF. 2004. Functional classification of the microbial feruloyl esterases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 63:647–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benoit I, Navarro D, Marnet N, Rakotomanomana N, Lesage-Meessen L, Sigoillot JC, Asther M, Asther M. 2006. Feruloyl esterases as a tool for the release of phenolic compounds from agro-industrial by-products. Carbohydr. Res. 341:1820–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castillo I, Requena T, Fernández de Palencia P, Fontecha J, Gobbetti M. 1999. Isolation and characterization of an intracellular esterase from Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei IFPL731. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86:653–659 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu S-Q, Holland R, Crow VL. 2001. Purification and properties of intracellular esterases from Streptococcus thermophilus. Int. Dairy J. 11:27–35 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez H, Curiel JA, Landete JM, de las Rivas B, López de Felipe F, Gómez-Cordovés C, Mancheño JM, Muñoz R. 2009. Food phenolics and lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 132:79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]