Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− is a monophasic serovar not able to express the second-phase flagellar antigen (H2 antigen). In Germany, the serovar is occasionally isolated from poultry, reptiles, fish, food, and humans. In this study, a selection of 67 epidemiologically unrelated Salmonella enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains isolated in Germany between 2000 and 2011 from the environment, animal, food, and humans was investigated by phenotypic and genotypic methods to better understand the population structure and to identify potential sources of human infections. Strains of this monophasic serovar were highly diverse. Within the 67 strains analyzed, we identified 52 different pulsed-field gel electrophoresis XbaI profiles, 12 different multilocus sequence types (STs), and 18 different pathogenicity array types. The relatedness of strains based on the pathogenicity gene repertoire (102 markers tested) was in good agreement with grouping by MLST. S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− is distributed across multiple unrelated eBurst groups and consequently is highly polyphyletic. Two sequence types (ST88 and ST127) were linked to S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B (d-tartrate positive), two single-locus variants of ST1583 were linked to S. enterica serovar Abony, and one sequence type (ST1484) was associated with S. enterica serovar Mygdal, a recently defined, new serovar. From the characterization of clinical isolates and those of nonhuman origin, it can be concluded that the potential sources of sporadic human infections with S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− most likely are mushrooms, shellfish/fish, and poultry.

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica is one of the leading causes of zoonotic food-borne disease worldwide. The main reservoir of Salmonella enterica is the intestinal tract of various animal species. The pathogen is transmitted to humans mainly by contaminated food, causing gastroenteritis and occasionally systemic infections (1). Globally, approximately 93.8 million human cases and 155,000 deaths annually have been estimated (2). The species is subdivided based on serological classification according to the White-Kaufmann-Le Minor scheme into almost 2,600 serovars (3). They are defined by an antigenic formula based on the presence of one somatic (O antigen) and two flagellar antigens (H1 and H2 antigens). The monophasic S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− does not express phase 2 flagellar antigen. It was reported as a fluctuating serovar in broiler flocks (4) and recognized in Spanish and Danish poultry slaughterhouses (5, 6). Occasionally, the serovar is isolated from human cases of gastroenteritis (7). Such cases were associated with exposure to turtles and considered to be possibly a specific variant of the biphasic d-tartrate-fermenting (dT+) S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B (also called variant Java) with seroformula 4,[5],12:b:1,2 (8). Initial characterization using multilocus sequence typing showed that S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains grouped in various eBurst groups (eBGs), some of them together with the biphasic S. enterica serovars Paratyphi B, Dublin, and Enteritidis (7, 9). DNA microarray analysis of seven 4,5,12:b:− strains related to Danish human cases supports clustering in two separate branches, one together with S. enterica serovars Dublin and Enteritidis and another with S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ (7).

The aim of our study was to identify potential sources of human infections caused by d-tartrate-positive S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− and to gain a better understanding of the population structure and genetic relatedness within this serovar. In addition, we compared it to other serovars, especially to those with O antigens 4,[5],12. For this purpose, we selected from our strain collections 67 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains isolated from poultry, reptiles, shellfish/fish, different food, and humans in Germany during the years 2000 to 2011 and investigated them by phenotypic and genotypic methods. Furthermore, the pathogenicity gene repertoire was determined and compared to estimate the potential health risk for humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain selection.

Monophasic S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains used were selected from the strain collections of the National Reference Laboratory for Salmonella at the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Berlin, Germany (NRL-Salm), and the National Reference Centre for Salmonella and Other Enterics at the Robert Koch Institute, Wernigerode, Germany (NRZ-RKI). All isolates were received from public and private diagnostic laboratories for serotyping (Table 1). To distinguish the S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains from S. enterica serovar Schleissheim (seroformula 4,12,27:b:−) or S. enterica subsp. salamae serovar 4,[5],12,[27]:b:[e,n,x], the following biochemical tests were performed with all monophasic strains (in parentheses are expected results for S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:−/Schleissheim/4,[5],12,[27]:b:[e,n,x]): fermentation of dulcitol (+/−/+), malonate (−/−/+), and gelatinase (−/+/+). All together, 39 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains isolated from humans suffering from gastroenteritis and 28 strains isolated from livestock, shellfish/fish, mushrooms, food, reptiles, and the environment were chosen for molecular typing (Table 2). The origins and sources of the strains cover various geographically distinct regions in Germany. All isolates were obtained between the years 2000 and 2011, and there was no obvious epidemiological link between them, i.e., not isolated at the same place or time or from the same individual.

Table 1.

Number and source of S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− isolates in Germany received by the NRL-Salm and NRZ-RKI

| Yr of isolation | Total no. of isolates |

No. of 4,[5],12:b:− isolates (source) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRL | NRZ | 4,5,12:b:− | 4,12:b:− | |

| 2000 | 3,915 | 6,696 | 7 (human), 2 (sheep), 1 (spice) | 1 (human) |

| 2001 | 3,605 | 7,635 | 3 (human), 1 (poultry meat), 1 (spice) | 2 (reptile) |

| 2002 | 4,411 | 6,300 | 8 (human), 3 (dried mushroom), 1 (reptile) | 1 (shellfish) |

| 2003 | 3,630 | 3,930 | 4 (human), 1 (fish/fish product), 1 (dried mushroom) | |

| 2004 | 3,604 | 3,691 | 2 (human), 1 (shellfish) | 3 (poultry) |

| 2005 | 4,090 | 3,655 | 6 (human), 1 (pet bird) | 1 (poultry) |

| 2006 | 3,887 | 3,333 | 7 (human), 1 (dried mushroom), 2 (othera) | |

| 2007 | 3,955 | 3,855 | 2 (human), 2 (othera) | 1 (poultry), 3 (othera) |

| 2008 | 3,606 | 3,205 | 4 (human), 1 (pig) | 1 (human), 2 (poultry) |

| 2009 | 4,111 | 3,646 | 21 (human) | |

| 2010 | 4,631 | 2,320 | 12 (human), 1 (shellfish) | 1 (human), 4 (poultry), 1 (othera) |

| 2011 | 3,793 | 2,439 | 17 (human), 1 (reptile) | 1 (reptile) |

| Total | 47,238 | 50,705 | 93 (human), 5 (dried mushroom), 1 (pet bird), 1 (pig), 1 (poultry meat), 2 (reptile), 3 (shellfish/fish), 2 (sheep), 2 (spice), 4 (othera) | 3 (human), 11 (poultry), 3 (reptile), 1 (shellfish), 4 (othera) |

Nonanimal origin.

Table 2.

S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains used for phenotypic and molecular analysis in this study

| Strain no. | Yr of isolation | Origin(s) | Resistancee | PFGE cluster | PFGE profile no. | MLST | PAT no. (microarray) | O antigen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01-02861 | 2001 | Food, spicery | SMX | A | 13 | 423 | 5 | 4,5,12 |

| 02-00002 | 2001 | Food, dried mushroom | Susceptible | A | 6 | 135 | NTf | 4,5,12 |

| 02-00059 | 2002 | Food, dried mushroom | Susceptible | A | 9 | 42 | 2 | 4,5,12 |

| 03-01178 | 2003 | Food, dried mushroom | Susceptible | A | 6 | 135 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 04-01012 | 2003 | Shellfish, shrimps | Susceptible | A | 15 | 1582 | 6 | 4,5,12 |

| 06-03656 | 2005 | Sludge | Susceptible | A | 7 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 06-02764 | 2006 | Food, dried mushroom | Susceptible | A | 5 | 135 | 7 | 4,5,12 |

| 10-00322 | 2009 | Shellfish, black tiger prawn | Susceptible | A | 16 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-00612 | 2011 | Reptile, turtle, feces | Susceptible | A | 18 | 1484 | NT | 4,12c |

| 11-02445 | 2000 | Human | Susceptible | A | 11 | 135 | NT | 4,12c |

| 11-02470 | 2000 | Human | Susceptible | A | 3 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02473 | 2001 | Human | Susceptible | A | 10 | 1589 | 12 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-01473 | 2002 | Human | Susceptible | A | 14 | 42 | 6 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02476 | 2003 | Human | Susceptible | A | 19 | 1588 | 10 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02482 | 2005 | Human | Susceptible | A | 12 | 135 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02486 | 2006 | Human | Susceptible | A | 1 | 135 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02487 | 2007 | Human | Susceptible | A | 4 | 135 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02491 | 2008 | Human | Susceptible | A | 11 | 135 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02493 | 2009 | Human | Susceptible | A | 17 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02497 | 2009 | Human | Susceptible | A | 2 | 42 | 9 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02501 | 2010 | Human | Susceptible | A | 8 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 01-02664 | 2001 | Reptile, organ | Susceptible | B | 20 | 1583 | 14 | 4,12c |

| 00-02409 | 2000 | Food, spicery | Susceptible | C | 40 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 01-00189 | 2000 | Chicken, meat | Susceptible | C | 21 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 02-00052 | 2002 | Food, dried mushroom | Susceptible | C | 33 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 02-04446 | 2002 | Reptile, Boiga dendrophila | Susceptible | C | 37 | 42 | 1 | 4,5,12 |

| 02-04643 | 2002 | Shellfish | Susceptible | C | 23 | 42 | 3 | 4,12c |

| 03-03172 | 2003 | Fish or fish product | Susceptible | C | 23 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-01531 | 2004 | Food, vegetable | Susceptible | C | 24 | 423 | 4 | 4,5,12 |

| 07-03684 | 2007 | Feed | Susceptible | C | 38 | 42 | 8 | 4,5,12 |

| 07-03824 | 2007 | Fertilizer | Susceptible | C | 32 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 08-00880 | 2008 | Pig | Susceptible | C | 35 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02471 | 2001 | Human | Susceptible | C | 25 | 423 | 2 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-01471 | 2002 | Human | Susceptible | C | 27 | 1578 | 11 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02475 | 2002 | Human | Susceptible | C | 28 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02479 | 2004 | Human | Susceptible | C | 22 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02480 | 2004 | Human | Susceptible | C | 34 | 423 | 2 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02485a,b | 2006 | Human | Susceptible | C | 26 | 42 | 9 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02488 | 2007 | Human | Susceptible | C | 29 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02490 | 2008 | Human | Susceptible | C | 29 | 423 | 2 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02494 | 2009 | Human | Susceptible | C | 31 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02496 | 2009 | Human | Susceptible | C | 39 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02498 | 2010 | Human | Susceptible | C | 29 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02499 | 2010 | Human | Susceptible | C | 38 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02500 | 2010 | Human | Susceptible | C | 30 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02502 | 2011 | Human | Susceptible | C | 36 | 423 | 2 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02503 | 2011 | Human | Susceptible | C | 22 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02504 | 2011 | Human | Susceptible | C | 29 | 423 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02505 | 2011 | Human | Susceptible | D | 41 | 679 | 13 | 4,5,12 |

| 00-02320 | 2000 | Sheep | SMX | E | 45 | 127 | 16 | 4,5,12 |

| 05-00829 | 2005 | Pet bird, feces | Susceptible | E | 47 | 42 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02467a,b | 2000 | Human | Susceptible | E | 42 | 88 | 17 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02474a | 2002 | Human | Susceptible | E | 45 | 127 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02478a | 2003 | Human | Susceptible | E | 43 | 127 | 15 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02483a,b | 2005 | Human | AMP CHL KAN SMX STR TET | E | 44 | 127 | 16 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02489a | 2008 | Human | Susceptible | E | 45 | 127 | 16 | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02492a | 2009 | Human | Susceptible | E | 45 | 127 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02495a | 2009 | Human | Susceptible | E | 46 | 127 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 11-02464a,b | 2010 | Human | Susceptible | E | 45 | 127 | 16 | 4,12c |

| 11-02465a | 2010 | Human | Susceptible | E | 45 | 127 | NT | 4,5,12 |

| 07-01889-2 | 2007 | Bird, quail, feces | NAL SMX STR TET | F | 48 | 1484 | NT | 4,12d |

| 04-02058 | 2004 | Turkey | SMX | G | 52 | 1484 | 18 | 4,12d |

| 07-01980 | 2007 | Feed | Susceptible | G | 51 | 1583 | NT | 4,12d |

| 08-02676 | 2008 | Chicken, environment | Susceptible | G | 52 | 1484 | NT | 4,12d |

| 10-01745 | 2010 | Turkey, meat | Susceptible | G | 49 | 1484 | 18 | 4,12d |

| 10-01843 | 2010 | Turkey | Susceptible | G | 50 | 1484 | NT | 4,12d |

| 11-02460 | 2008 | Human | Susceptible | G | 52 | 1484 | 18 | 4,12d |

Positive for fljB-1,2 according to Lim et al. (16).

fljB region sequenced. For GenBank accession no., see Materials and Methods.

Seven-base-pair deletion in the oafA gene, leading to a nonfunctional O:5 antigen.

Complete absence of the oafA gene.

Abbreviations: AMP, ampicillin; CHL, chloramphenicol; KAN, kanamycin; NAL, nalidixic acid; SMX, sulfamethoxazole; STR, streptomycin; TET, tetracycline.

NT, not tested.

A subset of 29 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains was chosen to study their pathogenicity gene repertoire using DNA microarrays. It was selected in order to reflect the diversity of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) XbaI profiles and MLST analysis observed among all of the 67 epidemiologically unrelated strains.

Serotyping.

Serotyping was performed according to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme (3) by slide agglutination with O- and H-antigen-specific sera (Sifin Diagnostics, Berlin, Germany). The H:z91 antiserum was purchased from Medco Diagnostika GmbH (München, Germany).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility of strains was tested against 14 antimicrobials by determining the MIC using the CLSI broth microdilution method (10) in combination with the semiautomatic Sensititre system (TREK Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, Ohio). Cutoff values (mg/liter) to be used to determine susceptibility to 10 antimicrobials were applied as described in the commission decision on a harmonized monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in poultry and pigs (2007/407/EC; http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32007D0407:EN:NOT), as follows: cefotaxime (FOT), >0.5; nalidixic acid (NAL), >16; ciprofloxacin (CIP), >0.06; ampicillin (AMP), >4; tetracycline (TET), >8; chloramphenicol (CHL), >16; gentamicin (GEN), >2; streptomycin (STR), >32; trimethoprim (TMP), >2; sulfamethoxazole (SMX), >256. Cutoff values for the remaining 4 antimicrobials were adopted from the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 2011 (http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/), and were as follows: colistin (COL), >2; florfenicol (FFN), >16; kanamycin (KAN), >32; and ceftazidime (TAZ), >2.

Genomic DNA purification.

DNA for PCRs and DNA microarray experiments was isolated from strains grown in Luria-Bertani broth (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 37°C for 16 to 18 h. A 1.6-ml aliquot was carried out for purification using the RTP bacteria DNA minikit (STRATEC Molecular GmbH, Berlin, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol with one additional step. After the cell lysis step at 95°C for 5 to 10 min and the cooling of samples for 5 min, a 5-μl aliquot of RNase (100 mg/ml) (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) was added and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The quality and quantity of DNA preparations was determined spectrophotometrically. For DNA labeling with fluorophores, a minimum of 4 μg DNA was used, and for PCRs, a 1-ng/μl dilution in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer was used.

MLST.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was carried out as previously described, including partial sequences of the seven housekeeping genes aroC, dnaN, hemD, hisD, purE, sucA, and thrA (11). Alleles and sequence types (STs) were assigned according to the MLST scheme available at http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/dbs/Senterica. Unknown alleles were submitted to the website and newly named. The analysis was carried out in BioNumerics version 6.6.4 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). The comparisons were made by advanced cluster analysis using the analysis template maximum spanning tree (MST) for categorical data on merged sequences of the seven genes. Complexes were designated eBurst groups (eBGs), and a new eBG (eBG242) was assigned according to the definition by Achtman et al. (9).

PFGE.

PFGE was performed according to the Pulse-Net protocol (12) by using the restriction enzyme XbaI for digestion of genomic DNA. The analyses of the gel images were carried out in BioNumerics version 6.6.4. The comparisons were made by cluster analysis using the Dice coefficient and unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA), with a position tolerance of 1.5% and optimization of 1.0%. Fragments that were smaller than 25 kb were not considered for cluster analysis.

DNA microarray analysis.

The DNA microarray used in this study was applied as previously described (13). All together, 80 pathogenicity gene markers, 22 fimbrial gene markers, and 49 resistance gene markers were analyzed for the 29 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains, representing the diversity of PFGE profiles. Moreover, markers for the flagellar genes were investigated (fljA, fljB, hin, fliC). Analysis of raw data was performed as previously described (13). After normalization (presence/absence of the gene), the data for each strain were imported in BioNumerics version 6.6.4 as a character value. For comparison, a cluster analysis with the simple matching binary coefficient, by using the UPGMA dendrogram type, was applied on the basis of the 80 pathogenicity and 22 fimbrial markers.

PCRs.

Testing for the presence of the oafA gene responsible for O:5-antigen expression in Salmonella was according to Hauser et al. (14) by using oligonucleotides P-439 and P-440, amplifying a 433-bp PCR product. To detect a 7-bp tandem repeat within the open reading frame (ORF), oligonucleotides P-439 and P-1072 were used, resulting in a PCR product of 170 bp. In case of loss of one 7-bp repeat, no PCR product was obtained, indicating a nonfunctional oafA gene. The ability of S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains to ferment d-tartrate was determined according to the PCR protocol described by Malorny et al. (15). Moreover, all serotypically monophasic S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains were tested by PCR with specific oligonucleotides for the presence of fljB-1,2 (H:1,2 antigen) according to Lim et al. (16).

DNA sequencing.

From two strains (11-02483 and 11-02464) belonging to ST127, one strain (11-02467) belonging to ST88, and one strain (11-02485) belonging to ST42, the fljA, fljB, hin, and iroB genes were sequenced. The region was amplified by three overlapping PCRs using the following oligonucleotides: (i) P-120 (CAGCGTAGTCCGAAGACGTGA) and P-915 (ACGAATGGTACGGCTTCTGTAACC), resulting in a 1,881-bp fragment for all four strains; (ii) P-1386 (GTCAGTAGCAACGTTAACTT) and P-1387 (ATGAGGTAAACGTACCGACA), resulting in a 2,129-bp fragment for strains 11-02467 and 11-02485 and resulting in a 1,126-bp fragment for strains 11-02483 and 11-02464; (iii) P-1392 (CGGAAAGTCTGCACAGAAC) and P-1551 (GCGAACTATCCAGGCACGA), resulting in a 1,647-bp fragment for all four strains. All PCR products were sequenced by the Qiagen GmbH sequencing service (Hilden, Germany). Single DNA sequence runs were assembled and analyzed by using the Lasergene software package (version 8.1; DNASTAR, Madison, WI). Oligonucleotides used for sequencing can be obtained on request. Sequence comparisons were performed by using the BLAST search at NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

The fliC gene was amplified from two ST1484 strains, 10-01745 and 11-02460, using oligonucleotides P-314 (AAGGAAAAGATCATGGCA) and P-60 (CCGTGTTGCCCAGGTTGGTAAT). The 1,286-bp PCR products were sequenced with oligonucleotides P-314 and P-60 by Qiagen GmbH.

Statistical methods.

The Simpson's index of diversity (ID) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the Comparing Partitions website (http://darwin.phyloviz.net/ComparingPartitions/index.php?link=Tool).

The chi-square test with a confidence interval of 95% (P < 0.05) was applied (http://www.daten-consult.de/frames/statrechnen.html) to check the significance in the number of strains attributed to each isolation source category.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The fljB DNA sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers HG003856 (strain 11-02483), HG003858 (11-02485), and HG003857 (11-02467). Partial fliC DNA sequences of strains 10-01745 and 11-02460 were deposited under accession numbers HG003859 and HG003860.

RESULTS

Prevalence of S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b.

Between 2000 and 2011, the National Reference Laboratory for Salmonella (NRL-Salm) received for diagnostic serotyping 47,238 Salmonella strains, isolated by public and private diagnostic laboratories across Germany from livestock, reptiles, shellfish/fish, food, feed, and the environment. Of these, 0.08% (40 strains) were assigned to S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− (Table 1). Strains were isolated mostly from poultry (12 strains), food (8 strains), and reptile (5 strains) and were isolated sporadically from shellfish/fish (3 strains), sheep (2 strains), pig (1 strain), and some other sources in Germany (Table 1). Twenty-one strains (52.5%) exhibited the O:5 antigen in addition to the O:4,12 antigen. O:5-antigen-negative strains were isolated mainly from poultry. Likewise, between 2000 and 2011, the National Reference Centre for Salmonella and other Enterics (NRZ-RKI) received 50,705 Salmonella strains isolated from humans with Salmonella infection in Germany. Of these, 96 strains (0.2%) were serotyped as S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− (Table 1). Most of the human S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains (93 strains, 95%) expressed the O:5 antigen. Data indicate a misbalance with respect to the frequency of strains isolated from humans expressing the O:5 antigen and such strains isolated from nonhuman origin, especially poultry.

Molecular analysis of the oafA gene (encoding the O:5-antigen factor) in O:5-antigen-negative strains showed that such strains either harbored a nonfunctional oafA gene due to a 7-bp deletion within the ORF or showed that the oafA gene was completely absent, especially in strains belonging to ST1484 (Table 2).

From the 136 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains identified in both collections, all together, 39 strains isolated from humans and 28 strains isolated from nonhuman origin were selected for extended molecular typing (Table 2). All three strains isolated from humans and not expressing the O:5 antigen were included. The remaining 36 strains (92%) isolated from humans and expressing the O:5 antigen were randomly selected, at least two strains from each year (2000 to 2011). All nonhuman strains were chosen without obvious epidemiological link.

Antimicrobial resistance.

Sixty-two of the 67 S. enterica 4,[5],12:b:− strains (93%) were susceptible to all 14 antimicrobials tested. Three strains were monodrug resistant to sulfamethoxazole (SMX), and two strains exhibited multidrug resistance to four or more antimicrobials (Table 2). Strain 07-01889-2 (quail isolate) was resistant to NAL, SMX, STR, and TET, and strain 11-02483 (human isolate) was resistant to AMP, CHL, KAN, SMX, STR, and TET. By DNA microarray analysis, we have found the following resistance genes: a blaTEM-1-like gene, encoding AMP resistance; aadA1 and aadA2,3,8, encoding STR/SPE resistance; a cmlA1-like gene, encoding CHL resistance; sul3, encoding SUL resistance; and tet(A), encoding TET resistance. Further markers indicated that specific antibiotic resistance genes are organized within class 1 and class 2 integrons in strain 11-02483.

Typing by PFGE.

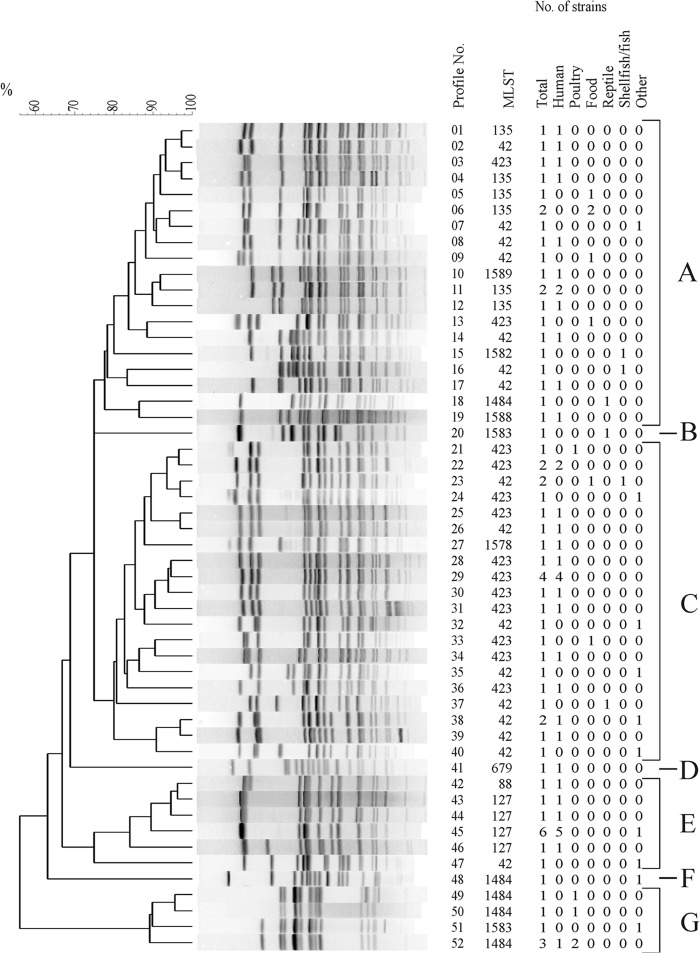

Fifty-two different XbaI profiles could be distinguished among the 67 strains analyzed (ID, 0.987; 95% CI, 0.976 to 0.998) (Fig. 1). They were classified into seven clusters (A, B, C, D, E, F, and G). The similarity coefficient (F value) for cluster A ranged from 0.75 to 0.97, and values were similar for clusters C (0.80 to 0.97), E (0.75 to 0.96), and G (0.89 to 0.96). Cluster A contained 21 of 67 strains (31%), cluster C contained 26 strains (39%), cluster E contained 11 strains (16%), and cluster G contained six strains (9%). Only one strain (1.5%) belonged to clusters B, D, and F. Related clusters F and G included all O:5-antigen-negative strains with complete absence of the oafA gene. These strains were isolated from poultry (four strains), bird (one strain), feed (one strain), and human (one strain). Clusters A to E contained only O:5-antigen-positive strains with five exceptions, all encoding a nonfunctional oafA gene due to a 7-bp deletion within the ORF (Table 2). Strains isolated from humans were distributed over all seven clusters. In respect to nonhuman strains, we observed a preference for strains isolated from mushrooms in cluster A and for strains isolated from poultry in cluster G. However, the observation was not significant.

Fig 1.

UPGMA dendrogram of PFGE profiles identified in 67 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains after digestion with XbaI. Profiles were numbered serially from 1 to 52. The number of strains belonging to each source (total, human, poultry, food, reptile, shellfish/fish, and other) and corresponding MLSTs are shown on the right side. Assigned clusters A to G are indicated.

MLST.

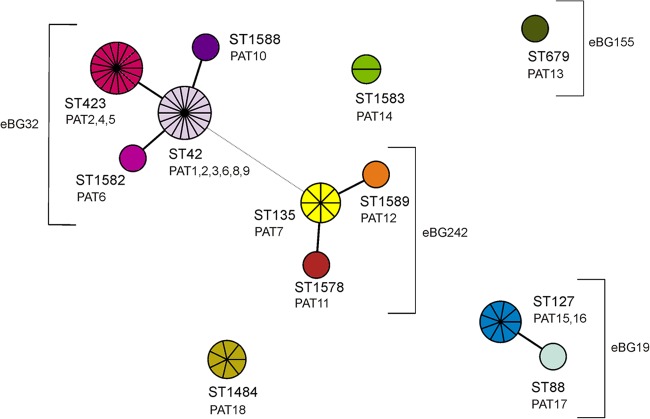

Twelve different sequence types (STs) were identified (ID, 0.830; 95% CI, 0.787 to 0.874). The most prominent STs were ST42 (27% of strains), ST423 (25%), ST127 (13%), ST135 (12%), and ST1484 (10%). Two strains (3%) belonged to ST1583, and one strain each (1.5%) belonged to ST88, ST679, ST1578, ST1582, ST1588, and ST1589. STs were categorized in three main complexes comprising more than one ST (Fig. 2). The founder of the largest complex (eBG32) was ST42. ST42 differed from ST423 in one nucleotide in the thrA allele, from ST1582 in one nucleotide in the hemD allele, and from ST1588 in one nucleotide in the sucA allele. The founder of the second complex is ST135, with single-locus variants ST1589 and ST1578 (eBG242). Both sequence types differed from ST135 only in one nucleotide each in another allele (hisD in ST1589 and dnaA in ST1578). ST42 differed from ST135 in four alleles, aroC (five nucleotides), dnaA (five nucleotides), sucA (one nucleotide), and thrA (nine nucleotides). The third complex (eBG19) consists of ST127 and ST88. ST127 differed from ST88 in one nucleotide in the dnaA allele. ST135 and ST127 differed in six alleles and share only an identical aroC allele. There are three unique STs among the strains under investigation, of which two (ST1583 and ST1484) were not yet assigned to any eBG, and one ST (ST679) was assigned to eBG155. They have no or a maximum of two common alleles (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Minimal spanning tree of MLST data on 67 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− isolates. Each circle refers to one ST subdivided into one pie slice per strain. STs that share six identical alleles are linked by a black line. STs sharing three alleles are linked by a gray dashed line. Based on their similarity, STs were grouped in three complexes; of these, two were already described as eBGs according to the nomenclature of Achtman et al. (9). Pathogenicity array types (PATs) found in each ST are shown below the designations.

The eBurst groups or single STs were associated to some extent with strains from a common source. Four STs (ST423, ST42, ST135, and ST127) were associated with more than six strains isolated from humans. ST127 was with one exception (00-02320; sheep) exclusively associated with human strains. Strains from poultry or poultry meat were assigned mainly to ST1484, also sharing the XbaI PFGE clusters F and G. Three out of the five strains isolated from mushrooms belonged to ST135. All four S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:b:− strains isolated from shellfish/fish belonged to eBG32.

We have compared the newly identified S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− ST1484, ST1578, ST1582, ST1583, ST1588, and ST1589 with all STs publicly available in the Salmonella-MLST database (http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/dbs/Senterica) in order to identify related STs in any other S. enterica serovars. Two single-locus variants (ST273 and ST442) of ST1583 were associated with S. enterica serovar Abony. Furthermore, ST1484 was a single-locus variant of ST252 observed in an S. enterica serovar Mygdal strain (4,12:z91:−).

Determination of pathogenicity genes.

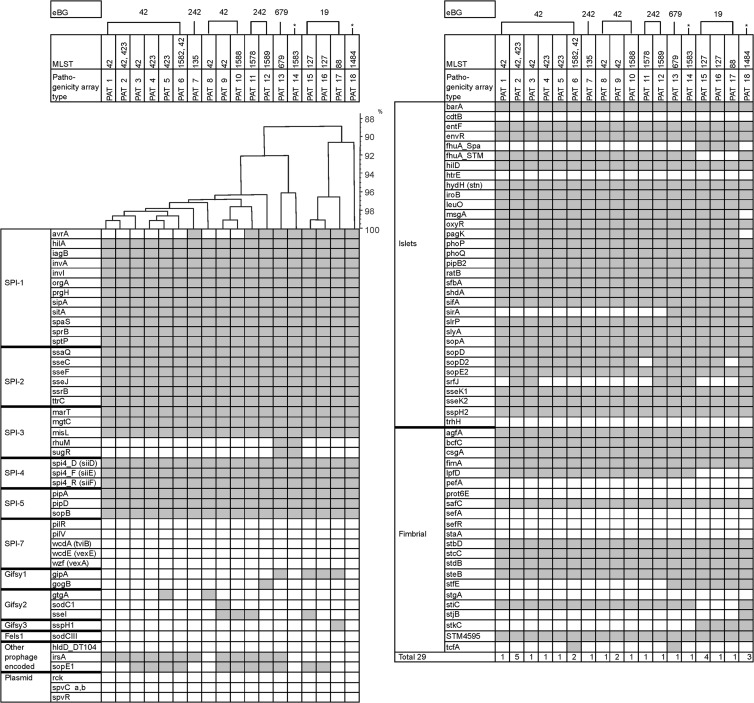

Eighteen different pathogenicity array types (PATs) were identified among the 29 strains tested (Table 2). PATs differed in up to 24 of 102 markers tested (Fig. 3). We have observed certain relatedness between PATs and specific eBGs. ST42 strains, the founder of eBG32, are linked to six different PATs, and ST423 strains are linked to three different PATs. All those PATs are closely related. PATs associated with eBG242 cluster together with PATs of eBG32. For ST127 and ST88 strains (eBG19), three similar but distinct PATs were found. The remaining PATs (13, 14, and 18) are subdivided in specific branches in accordance with their specific STs (ST679, ST1583, and ST1484).

Fig 3.

Virulence determinant microarray for 29 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains analyzed. On the left side, the analyzed genes are indicated and grouped according to their particular genomic location (SPI-1 to SPI-7; prophages Gifsy-1, Gifsy-2, Gifsy-3, and Fels-1; plasmids and islets) or function (fimbrial). At the top, assigned pathogenicity array types (PATs) and corresponding eBGs are indicated. The asterisks show the STs that do not yet belong to an eBG. The hybridization result of each type is shown by row. A white box indicates the absence and a gray box indicates the presence of the target sequence. SPI, Salmonella pathogenicity island.

A number of markers targeting Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1), SPI-2, and SPI-3 were absent in certain strains or eBGs. All strains belonging to eBG32 (PATs 1 to 6 and 8 to 10) lacked the avrA gene located in SPI-1 (encoding a protein inhibiting the key proinflammatory immune response) and rhuM and sugR genes, both located in SPI-3. In PATs 11, 12, and 15 to 18, the avrA gene was present, but the rhuM and sugR genes (SPI-3) were missing. The six PATs (PATs 1 to 3, 6, 8, and 9) linked with ST42 differed from each other in one to five of the seven markers for genes gtgA, sodC1, sseI, irsA, sopE1, srfJ, and tcfA. Three PATs (PATs 2, 4, and 5) belonged to ST423. These PATs differed in single markers for gtgA, sopE1, or srfJ. ST127 (PATs 15 and 16) and ST88 (PAT 17) strains belonging to eBG19 differed in four pathogenicity gene markers (sseI, sspH1, sopE1, and sopD2). Markers for msgA (SsrB regulator) and pagK (PhoPQ-activated protein) were absent only in PAT 18 (ST1484).

Serotype marker genes in S. enterica 4,[5],12:b.

Genes encoding the repressor for phase 1 flagellin (fljA), the structural phase 2 flagellin unit (fljB), and a DNA invertase (hin) are ordered consecutively in the Salmonella genome. Three different combinations for these markers were found within the 29 S. enterica 4,[5],12:b:− strains tested. DNA microarray probes indicating the presence of fljA, fljB_1,x and hin genes were negative in 22 strains. In five strains (all belonging to ST127), the probes for genes fljA and fljB_1,x were present, but hin was absent. Two strains (11-02467 [ST88] and 11-02485 [ST42]) were positive for all three probes, fljA, fljB_1,x, and hin.

We have sequenced the fljB region of two ST127 strains (11-02464 and 11-02483), one ST88 strain (11-02467), and one ST42 strain (11-02485) to identify the genetic background leading to nonfunctional phase 2 H-antigen expression. Both ST127 strains lacked the hin gene exactly between the recombination sites hixL and hixR (17), but genes fljA and fljB were present. In the ST88 strain, genes fljA and fljB as well as the hin gene were present in a regular arrangement. However, compared to the DNA sequence of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (GenBank accession no. NC_003197), there was a 1-bp deletion at position 2915827 within a noncoding region downstream of hin. Sequence comparison revealed 100% identity with the flagellin-encoding gene fljB of S. enterica serovars Newport, Hissar, Litchfield, Stanley, and Schottmuelleri, whereas the identity to fljB-1,2 carried in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, Paratyphi B dT+, and Saintpaul strains was 99%. All these serovars express the phase 2 H:1,2 antigen. In the monophasic ST42 strain, all three genes, fljA, fljB, and hin, were present. However, there were several polymorphic sites compared to the ST88 strain. The ST42 fljB gene differed from the ST88 fljB gene in six nucleotides, and it was 100% identical to the fljB gene of S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strain SPB7 (GenBank accession no. CP000886.1). The DNA sequence revealed no hints which could explain a nonfunctional phase 2 H-antigen expression of the strain.

The phase 1 flagellin gene fliC is chromosomally located apart from fljB. The fliC-b (encoding the H:b structural phase 1 flagellin unit) marker was positive in all 29 S. enterica 4,[5],12:b:− strains tested by microarray analysis. We have also sequenced the fliC gene of two ST1484 strains and found only one (10-01745) or two (11-02460) nonsynonymous polymorphic sites compared to the unique published fliC-z91 gene sequence of S. enterica serovar Mygdal (GenBank accession no. GQ280905.1). Agglutination using H:z91 antiserum was positive for all strains belonging to ST1484 but negative for representative S. enterica 4,[5],12:b:− strains belonging to all other MLST types. This indicates that a single amino acid exchange in the H:b structural phase 1 flagellin protein leads to a positive agglutination reaction with H:z91 and H:b antisera (G in ST1484 strains → D in S. enterica serovar Mygdal). Usually, fliC-z91 of S. enterica serovar Mygdal differs from fliC-b in 15 (GenBank accession no. DQ838210.1) to 48 (CP000886.1) nucleotides.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the population structure and pathogenicity gene repertoire of S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:−, as well as potential infection sources for humans, were investigated. The monophasic serovar is not frequently isolated from humans and animals, but occasional cases were reported (8). MLST data of 67 strains analyzed showed that S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− is highly polyphyletic, which is in contrast to another monophasic S. enterica serovar, the worldwide-expanding S. enterica serovar Typhimurium variant 4,[5],12:i:− (18, 19). All together, 12 different STs were found clustering in four eBurst groups and two additional unrelated STs. The genetic diversity was supported by PFGE data, assigning 52 XbaI profiles with a discrimination index of 0.987. This clearly indicates that the serovar is composed of various phylogenetic lineages lacking a common ancestor.

Relatedness of S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− sequence types to other serovars.

Some of the STs observed in S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− were identical to or single-locus variants of STs associated with other S. enterica serovars characterized by the same somatic and H1 antigen but expressing in addition the H2:1,2 antigen (serovar Paratyphi B dT+) or the H2:e,n,x antigen (serovar Abony). To our surprise, a single-locus variant (ST252) of our ST1484 S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains, which are strongly associated with poultry, was found in an S. enterica serovar Mygdal strain (4,12:z91:−). S. enterica serovar Mygdal was newly identified and recently added to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme (20). The original reference strain was isolated from swine feces in 2003 in Denmark. DNA sequencing of the fliC gene in two ST1484 strains supports the close relationship to ST252. The fliC-z91 gene of S. enterica serovar Mygdal and fliC-b gene of S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− ST1484 strains differed only in up to two nonsynonymous nucleotides, leading to a positive slide agglutination with H:z91 and H:b antisera. From our data, we conclude that certain S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains are monophasic variants of closely related biphasic serovars with which they share the O and H1 antigens. Others are closely related to monophasic serovars (e.g., Mygdal) sharing highly similar H1 antigens. However, for most STs belonging to S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:−, related serovars have not been identified. With the increasing generation of MLST data, further genetic relationships to other serovars will be found.

Molecular screening for the presence of the fljB gene in S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− was with two exceptions in accordance with the monophasic phenotype. The exceptional strains (11-02467, 11-02485) were assigned to ST88 and ST42. ST88 occurred also in biphasic S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ (21). Both types of ST88 strains possess fljA, fljB, and hin genes. In the monophasic ST88 strain, a single base pair deletion in the intergenic region between hin and iroB might be the cause of a nonfunctional phase 2 flagellin expression. However, we speculate that the hin gene is locked and unable to switch to the “on” orientation for cotranscription of fljA and fljB. The fljB sequence of the ST88 strain was 100% identical to the fljB gene of S. enterica serovars Newport, Hissar, Litchfield, Stanley, and Schottmuelleri, probably imported by horizontal gene transfer. Whether the same fljB allele occurs in biphasic ST88 S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains has to be elucidated. ST127 strains lacked the hin gene, but the fljA and fljB genes were identical to those of the monophasic ST88 strain. This supports the close relationship of ST127 and ST88 strains, as also indicated by MLST.

Potential sources of human infection.

The sources of S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains of nonhuman origin isolated in Germany between 2000 and 2011 (40 strains) were diverse. Most strains were isolated from poultry (30%), mushrooms (12.5%), or shellfish/fish (10%), but due to the genetic variability and low prevalence, the serovar could not be associated with a specific source of human infection. However, MLST analysis revealed one specific type which is strongly connected to poultry. Strains isolated from poultry belonged predominantly to ST1484, and one out of the 39 human strains investigated clustered into this ST. This indicates that there is human exposure to poultry contaminated with this S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− type, but clinically apparent infections are rare. We have previously described two similar examples in S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains belonging to ST28 and in S. enterica serovar 4,12:d:− strains (ST279). These strains were also highly associated with poultry but rarely isolated from humans (13, 21). However, because of completely different alleles, S. enterica serovar 4,12:b:− ST1484 strains do not represent a monophasic variant of S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ ST28 strains, as might be concluded from seroformula, or are related to S. enterica serovar 4,12:d:− strains. Of higher risk for humans seems to be the exposure of mushrooms contaminated with S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:−. Three out of five strains isolated from mushrooms and five strains from humans belonged exclusively to ST135 and, therefore, were likely connected to the consumption of mushrooms. The source of two mushroom strains (ST135) was linked to an import from Asia.

Most of the S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− strains (55%) investigated belonged to eBG32. The group was highly diverse in respect to PFGE profiles and PATs. Predominantly, all four strains isolated from shellfish/fish were found in this group, along with human strains, indicating a seafood-associated subtype which is able to infect humans. However, single strains isolated from a number of various other sources were also found in this lineage. eBG32 and eBG242 showed variation in the pathogenicity gene repertoire but could be clearly differentiated from eBG19 and other singleton STs. Some of these differences might have an influence on the virulence in humans and animals.

Human salmonellosis caused by S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− has been reported from Spain (8). Contact with turtles has been identified as the potential source of infection. We have observed in our study an identical PFGE XbaI profile in two strains isolated from human and feed (XbaI profile no. 38), as previously described by Hernández et al. (8). Whether the feed (dried fish) was intended for reptiles is unknown. However, in our study, two strains isolated from reptiles were distantly related to each other and to the one described previously. Therefore, based on our data, we cannot conclude that reptiles contaminated with S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− are a major source of human infection.

In conclusion, S. enterica serovar 4,[5],12:b:− is a polyphyletic serovar which can be isolated from many different sources. The serovar is represented by several phylogenetic lineages and is not generally a monophasic variant of S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+. Consumption of contaminated mushrooms and shellfish/fish is a potential source of human infection. The pathogenicity gene repertoire of the different phylogenetic lineages indicates that some lineages might be more virulent for humans than others. Currently, the serovar seems not to pose a major threat for humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), FBI-Zoo (grant no. 01KI1012I [Federal Institute for Risk Assessment] and 01KI1012F [Robert Koch Institute]).

We thank Istvan Szabo, Andreas Schroeter, Manuela Jaber, Martha Brom, and Katharina Thomas for serotyping and antimicrobial resistance testing of strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 June 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Thorns CJ. 2000. Bacterial food-borne zoonoses. Rev. Sci. Tech. 19:226–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Kirk M, O'Brien SJ, Jones TF, Fazil A, Hoekstra RM, International Collaboration on Enteric Disease ‘Burden of Illness' Studies 2010. The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:882–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimont PAD, Weill F-X. 16 April 2013, accession date Antigenic formulae of the Salmonella serovars, 9th ed WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France: http://www.pasteur.fr/ip/portal/action/WebdriveActionEvent/oid/01s-000036-089 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chadfield M, Skov M, Christensen J, Madsen M, Bisgaard M. 2001. An epidemiological study of Salmonella enterica serovar 4,12:b:− in broiler chickens in Denmark. Vet. Microbiol. 82:233–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carramiñana JJ, Yangüela J, Blanco D, Rota C, Agustín AI, Herrera A. 1997. Potential virulence determinants of Salmonella serovars from poultry and human sources in Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 54:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen JE, Brown DJ, Madsen M, Bisgaard M. 2003. Cross-contamination with Salmonella on a broiler slaughterhouse line demonstrated by use of epidemiological markers. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94:826–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litrup E, Torpdahl M, Malorny B, Huehn S, Christensen H, Nielsen EM. 2010. Association between phylogeny, virulence potential and serovars of Salmonella enterica. Infect. Genet. Evol. 10:1132–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernández E, Rodriguez JL, Herrera-León S, García I, de Castro V, Muniozguren N. 2012. Salmonella Paratyphi B var Java infections associated with exposure to turtles in Bizkaia, Spain, September 2010 to October 2011. Euro Surveill. 17:pii=20201 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achtman M, Wain J, Weill FX, Nair S, Zhou Z, Sangal V, Krauland MG, Hale JL, Harbottle H, Uesbeck A, Dougan G, Harrison LH, Brisse S, S. enterica MLST Study Group 2012. Multilocus sequence typing as a replacement for serotyping in Salmonella enterica. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002776. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A7, 7th ed, vol 23 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kidgell C, Reichard U, Wain J, Linz B, Torpdahl M, Dougan G, Achtman M. 2002. Salmonella typhi, the causative agent of typhoid fever, is approximately 50,000 years old. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, Cameron DN, Hunter SB, Swaminathan B, Barrett TJ. 2006. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huehn S, Bunge C, Junker E, Helmuth R, Malorny B. 2009. Poultry-associated Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar 4,12:d:− reveals high clonality and a distinct pathogenicity gene repertoire. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1011–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser E, Junker E, Helmuth R, Malorny B. 2011. Different mutations in the oafA gene lead to loss of O5-antigen expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110:248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malorny B, Bunge C, Helmuth R. 2003. Discrimination of d-tartrate-fermenting and -nonfermenting Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica isolates by genotypic and phenotypic methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4292–4297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim YH, Hirose K, Izumiya H, Arakawa E, Takahashi H, Terajima J, Itoh K, Tamura K, Kim SI, Watanabe H. 2003. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay for selective detection of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 56:151–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes KT, Youderian P, Simon MI. 1988. Phase variation in Salmonella: analysis of Hin recombinase and Hix recombination site interaction in vivo. Genes Dev. 2:937–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Switt AI, Soyer Y, Warnick LD, Wiedmann M. 2009. Emergence, distribution, and molecular and phenotypic characteristics of Salmonella enterica serotype 4,5,12:i. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 6:407–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauser E, Tietze E, Helmuth R, Junker E, Blank K, Prager R, Rabsch W, Appel B, Fruth A, Malorny B. 2010. Pork contaminated with Salmonella enterica serovar 4,[5],12:i:−, an emerging health risk for humans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4601–4610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guibourdenche M, Roggentin P, Mikoleit M, Fields PI, Bockemühl J, Grimont PA, Weill FX. 2010. Supplement 2003-2007 (no. 47) to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme. Res. Microbiol. 161:26–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toboldt A, Tietze E, Helmuth R, Fruth A, Junker E, Malorny B. 2012. Human infections attributable to the d-tartrate-fermenting variant of Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi B in Germany originate in reptiles and, on rare occasions, poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:7347–7357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]